Abstract

Background. The assessment of motor function is vital in post-stroke rehabilitation protocols, and it is imperative to obtain an objective and quantitative measurement of motor function. There are some innovative machine learning algorithms that can be applied in order to automate the assessment of upper extremity motor function.

Objectives. To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of machine learning algorithms for assessing upper limb motor function in post-stroke patients and compare these algorithms to clinical assessment.

Materials and methods. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database. The review was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The search was performed using 6 electronic databases. The meta-analysis was performed with the data from the correlation coefficients using a random model.

Results. The initial search yielded 1626 records, but only 8 studies fully met the eligibility criteria. The studies reported strong and very strong correlations between the algorithms tested and clinical assessment. The meta-analysis revealed a lack of homogeneity (I2 = 85.29%, Q = 48.15), which is attributable to the heterogeneity of the included studies.

Conclusions. Automated systems using machine learning algorithms could support therapists in assessing upper extremity motor function in post-stroke patients. However, to draw more robust conclusions, methodological designs that minimize the risk of bias and increase the quality of the methodology of future studies are required.

Key words: stroke, machine learning, computer-assisted diagnosis

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 15 million people worldwide suffer a stroke every year.1 Of these, approx. 5 million are left with a disability that limits their capacity to perform daily activities. They are also prone to becoming depressed or stressed due to limitations of their motor functions.2

Because of these conditions, patients have to participate in rehabilitation programs aimed at improving their quality of life. These programs support them in regaining motor function in the areas affected by the stroke.3 First, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment to properly select the best therapeutic options.4 There are numerous motor assessment tests to evaluate the degree of upper limb disability, including the Fugl–Meyer Assessment5 and the Wolf Motor Function Test.6 In general, each test consists of a series of tasks to be performed by the patient, and the therapist evaluates those tasks using measures based on their observations. However, motor assessments require prior training of the examiners; therefore, in many cases, the evaluation tends to be subjective.7 To avoid this problem, there is a great interest in the development of automated systems aimed at achieving objective and quantitative assessments for rehabilitation after strokes. Automated quantitative assessment systems can be used with home-based systems that assist patients in evaluating improvements during home-based exercise programs.

Thanks to technological advances, significant progress has been made in recent years in measuring and analyzing vital signs and human movement through artificial intelligence (AI).8, 9, 10 Furthermore, AI has provided a technical basis for the automation of many processes,11 such as rehabilitation12 and evaluation of upper limb motor function.

Objectives

Based on these points, the main objective of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of machine learning algorithms in assessing upper limb motor function in post-stroke patients, and compare these algorithms to clinical assessment.

Materials and methods

Study protocol and record

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines13 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.14 In addition, the review protocol was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the registration number PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021257217 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021257217).

Eligibility criteria, information sources

and search strategy

The articles included assessed upper limb motor function in post-stroke patients through machine learning algorithms compared to standard clinical assessment. The outcomes of interest were diagnostic accuracy, specificity, and/or sensitivity. Articles were excluded if they assessed motor function to predict patient recovery time; case series and literature reviews were also excluded. The patient-intervention-comparison-outcome (PICO) strategy was used to identify the key words used (Table 1). The electronic search was performed in May 2021 and updated in October 2021. The information sources and algorithms used in each database are shown in Table 1.

Selection process

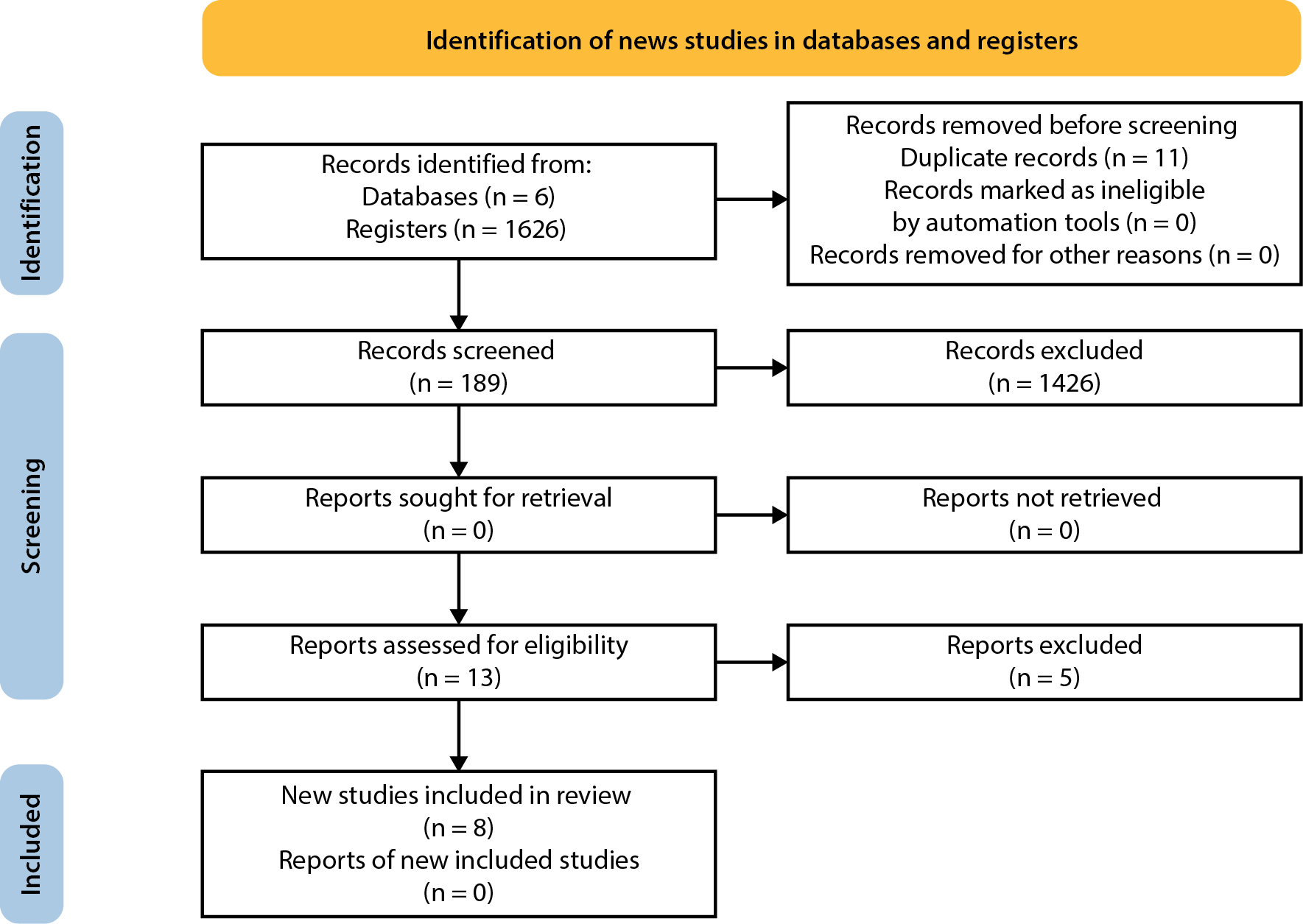

Three authors (JFAA, ARF and RRR) independently reviewed the registries obtained by the search. Duplicate records were removed using Mendeley Desktop v. 1.19.8 Reference Manager (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands).15 Studies that met the eligibility criteria by reading the title and abstract were retrieved in full text. Any disagreement was addressed by another reviewer (LAF) who made the final decision. The selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Data collection process and data items

The relevant data of the included articles were collected in a standardized Microsoft Excel 2019 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA). The data included study design, characteristics of the population, type of machine learning algorithm, data acquisition device, reference test, relative sensitivity, relative specificity, and confidence intervals. Three reviewers were responsible for data extraction (MVT, JGG and LAFM). When there were disagreements, the reviewers held discussions until reaching a consensus. The researchers of the original articles were contacted via e-mail for missing or additional details.

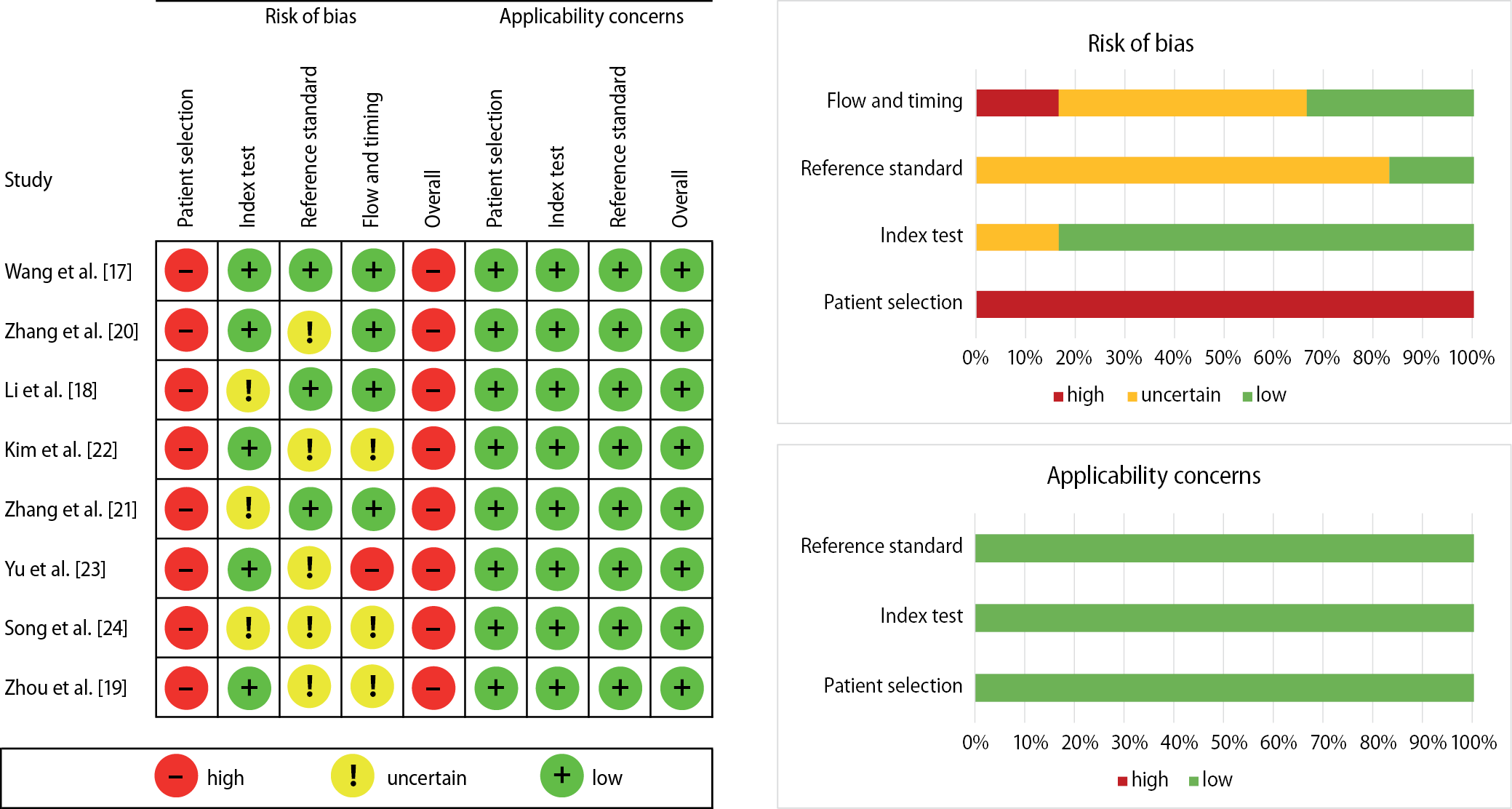

Assessment of risk of bias and quality of the included studies

Three reviewers (EPCM, EPC and ARF) assessed the risk of bias of the included studies following Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.14 Additionally, the reviewers performed a quality assessment of the studies using the modified QUADAS-2 tool (Table 2),16 which encompasses the following 5 domains: sample selection, index test, reference standard, flow rate, and time. In case of disagreements in the assessment of risk of bias, the differences were resolved by consensus of the research group.

Summary of results

A formal narrative synthesis concerning the accuracy of the machine learning algorithms to determine the level of upper limb impairment was performed.

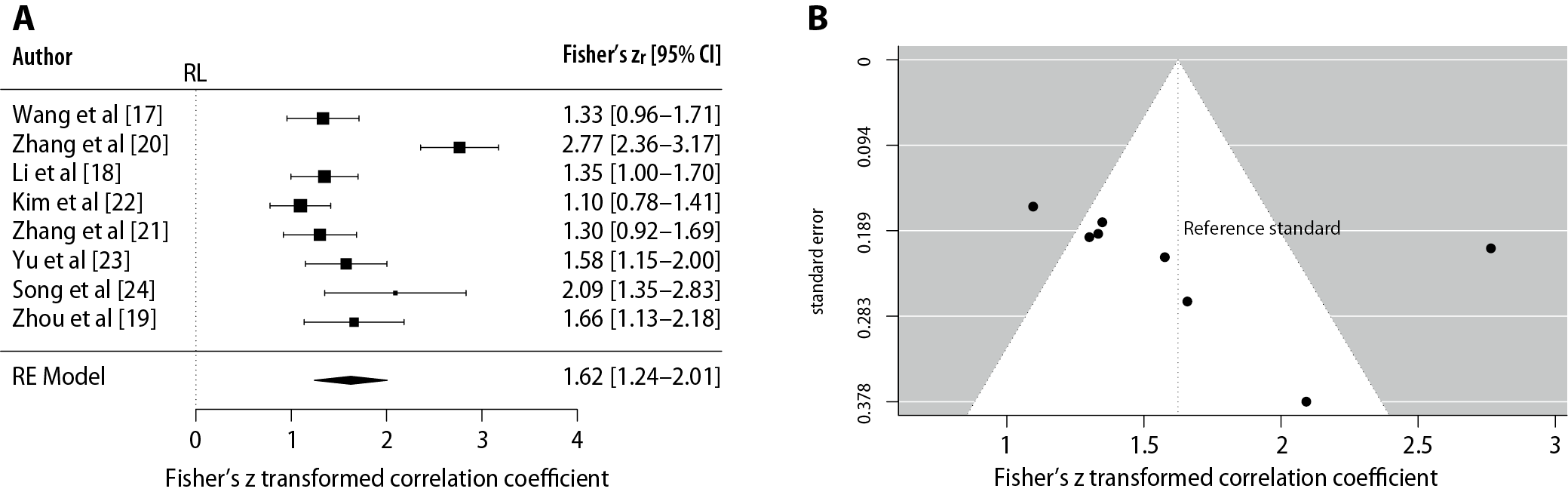

Meta-analysis

In order to assess the accuracy of the machine learning algorithms in determining the level of upper limb impairment, correlation coefficients were explored. The meta-analysis was performed using the metafor package (v. 3.0-2) of the R software program (R Development Core Team, 2011; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the data from the correlation coefficients, using a random model. In addition, a test for funnel plot asymmetry and a likelihood ratio test for publication bias were performed using the metafor and weight packages, respectively.

Results

Selection and characteristics of the studies

The initial search yielded 1626 records. Eleven duplicate records were eliminated, leaving 1615 records that were reviewed by title and abstract. As a result of this review, 189 records related to the research question were identified. Of these, 13 full-text studies were assessed, but only 8 met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). All articles had an observational study design.

Results of the individual studies

Data acquisition

The researchers used different modalities for data acquisition in the included studies. Some researchers applied more than one device, while others used a single device. Of these, the most common was surface electromyography (sEMG), followed by electroencephalography (EEG), Microsoft Kinect, inertial measurement unit (IMU), accelerometer, flex sensors, and cell phone.

For sEMG, data are obtained through noninvasive electrodes, which measure the time and intensity of the electrical signals from the muscles. Among the included studies, Wang et al.,17 Li et al.18 and Zhou et al.19 used this device.

Zhang et al. used EEG, which involves placing electrodes on the scalp. Each electrode sends a signal to a device called an electroencephalograph, which displays the rhythmic fluctuation of the brain’s electrical activity (brain waves) in real time.20

An IMU is an electronic device that measures and reports velocity, orientation and, in some models, gravitational forces. Data are obtained from a combination of accelerometers, gyroscopes and magnetometers. Inertial measurement units are small devices that are placed noninvasively on the patient’s skin to obtain motion data in 3 dimensions. Among the included studies, Li et al.18 used an MPU-9250 device (InvenSense, San Jose, USA), while Zhang et al.21 used an MPU-6050 device (Xsens Technologies, Los Angeles, USA).

Kim et al. used Microsoft Kinect (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA).22 This device has cameras for motion and depth detection. It was initially developed as a video game device for Microsoft Xbox console; it tracks players’ movements while they interact with a game. The Kinect consists of an infrared light projector and a red-green-blue (RGB) video camera. The reflected infrared light is converted into depth data and calibrated with RGB data to distinguish shapes.

Yu et al. used an ADXL345 accelerometer and flex sensors.23 An accelerometer is an electronic device that measures the vibration or acceleration of the movement of a structure. The force generated by the vibration or change in motion (acceleration) is detected, and an electrical charge is generated that is proportional to the force exerted on it. Accelerometers also play an important role in determining orientation and direction. Flex sensors are small strips composed of polymeric ink with embedded conductive particles; their function is to measure the resistivity when the sensor is flexed. Subsequently, the resistance value is converted into joint rotation angles.

Finally, Song et al. used an accelerometer and gyroscope integrated into a cell phone (iPhone 7, running an iOS 11.2.5 operating system; Apple Inc., Cupertino, USA).24 Through this device, the researchers obtained the position and location of the hand in 3 dimensions.

Machine learning algorithms

The machine learning algorithms used for the assessment of motor function are briefly described below.

The machine learning algorithms using supervised learning included the support vector machine (SVM), which was employed by Wang et al.17 and Zhou et al.19 Support vector machine is a learning-based method for solving classification and regression problems. This algorithm is a decision function based on the hyperplane concept, a boundary that distinguishes several points in different classes and separates them.25 In the same sense, Wang et al. used the backpropagation neural network (BPNN).17 This algorithm applies the concept of gradient descent. Given an artificial neural network and an error function, this method calculates the gradient of the error function concerning the weights of the neural network. Wang et al.17 and Zhou et al.19 applied the random forest (RF) algorithm, which is a set of decision trees that are independent of each other. The advantage of the RF algorithm is that it can be used for both classification and regression problems, which constitute the majority of the current machine learning systems.

Continuing with supervised learning algorithms, Zhang et al. employed the convolutional neural network (CNN).20 This type of neural network processes its layers by emulating the visual cortex of the human eye to recognize different features in the inputs. Convolutional neural network incorporates several specialized hidden layers into a hierarchy. The first layers can detect simple patterns, such as lines, curves and others; this is then specialized to deeper layers that recognize increasingly complex shapes. In the same way, Li et al. applied the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), which is a regression analysis method used to model the relationship between a dependent variable (which can be a vector) and one or more explanatory variables.18 On the other hand, Kim et al. applied the artificial neural network (ANN), which is a computational learning system that uses a network of functions to understand and translate data input (usually patterns and relationships) into a desired output.22 The concept of artificial neural network was inspired by human biology and how neurons in the human brain interconnect to understand human sensory inputs. Likewise, Zhou et al. applied linear discriminant analysis (LDA), which is based on the rule of maximum a posteriori probability and Bayesian principles, to find a linear combination of features that characterize or separate 2 or more classes of objects or events.19

Finally, Zhang et al. applied the K-nearest neighbor (KNN), which classifies an unknown sample by initially calculating the distance from that sample to all training samples.21 This algorithm is used to rank values by looking for the “most similar” (closest) data points learned in the training stage and estimating new points based on that ranking. Similarly, Yu et al. used extreme learning machine (ELM).23 This algorithm includes several hidden neurons in which the input weights are randomly assigned. In this type of network, data only go in one direction through a series of layers. It is implemented fully automatically without iterative tuning, and, in theory, no user intervention is required. Likewise, Song et al. applied the decision tree (DT).24 This algorithm is the most frequently used in classification and regression problems, in which categorical or continuous input and output variables are used. Decision tree is composed of a root node, several internal nodes and several terminal nodes. The goal of the tree is to make the optimal choice at the end of each node. The name itself suggests that this technique uses a flowchart as a tree structure to show the predictions that result from a series of splits based on the features of the inputs.

Correlation with clinical analysis

In the included studies, the algorithms that showed a very strong correlation with the Fugl–Meyer Assessment test were CNN,20 DT,24 SVM,19 and ELM.23 The algorithms that presented a strong correlation were the framework with the union of SVM, BPNN, and RF,17 LASSO,18 and ANN.22 Finally, the KNN algorithm presented a strong correlation with the Brunnstrom evaluation scale (Table 3).21

Risk of bias and quality assessment

At the QUADAS-2 assessment, 100% of the included studies showed a high risk of bias, whereas the applicability section showed a low risk of bias in 100% of the studies. In addition, 87.5% of the studies did not describe how the patients in the sample were enrolled; therefore, domain 1 showed a high risk of bias (Figure 2).

Meta-analysis

The results of the meta-analysis suggest that there is a correlation between clinical assessment (Fugl–Meyer Assessment and Brunnstrom’s evaluation scale) and machine learning algorithms in the evaluation of upper limb motor function (Fisher’s zr (95% confidence interval (95% CI)) = 1.62 (1.24–2.00), p < 0.001). In addition, the absence of homogeneity was observed (I2 = 85.29%, Q = 48.15), which is attributable to the heterogeneity of the studies. The result of the test for funnel plot asymmetry was z = 1.1914, p = 0.2335, limit estimate (as sei ≥ 0): b = 0.7919 (95% CI: −0.6242–2.2080), as shown in Figure 3A,B. In addition, a likelihood ratio test was conducted comparing the adjusted model, including the selection to its unadjusted random-effects counterpart. The Vevea and Hedges weight-function model resulted in a likelihood ratio of χ2 = 0.3062, p = 0.58. Taken together, this suggests that there was no publication bias.

Discussion

A wide variety of machine learning algorithms are described in this systematic review. Out of the 8 included studies, 6 (75.0%) used only one algorithm to assess motor function; 3 of these presented a very strong correlation20, 23, 24 and 3 showed a strong correlation18, 21, 22 between the algorithms for motor assessment and clinical assessment. Two (25.0%) of the studies employed 3 algorithms: Zhou et al. showed a very strong correlation19 and Wang et al. reported a strong correlation17 between motor assessment algorithms and clinical evaluation. The evidence is not conclusive concerning whether better results are obtained with the exclusive use of a single algorithm or with a combination of algorithms. This is contrary to Wang et al., who are in favor of combined use.17

In machine learning, the number of samples required for training the machine learning model depends on the complexity of both the problem to be solved and the algorithm developed.26 Although there is no established minimum number of training samples,27 there are experiments that have indicated that increasing the size of the dataset improves performance.27, 28, 29 Therefore, once the algorithm starts to detect patterns, it is best to increase the sample size. Of the included studies, 4 did not report the number of samples used for training,18, 21, 22, 24 while the rest reported using 992,19 1080,17 1680,23 and 196020 samples; however, they did not justify the sample size used.

Data acquisition was performed using various sensors in the training of the algorithm and the evaluation of the upper limb motor function. Some are readily available (cell phone24 and inertial sensors18, 21, 23), while others are specialized equipment that would limit their use to healthcare units (electromyography17, 18, 19 and electroencephalography20).

The gold standard for evaluating motor function is clinical assessment, for which various assessment tools are available. These tools assess either general motor function (Medical Research Council (MRC) Scale and Fugl–Meyer Assessment) or specific areas of impairment (upper limb function, trunk function, gait ability, and spasticity). In this regard, the MRC Scale, the Frenchay Arm Test, and the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) are specific to the upper limb motor function.30

The Fugl–Meyer Assessment is a performance-based index of the stroke-specific impairment.31 It is designed to assess motor functioning, sensation, balance, joint range of motion, and joint pain in patients with post-stroke hemiplegia. It is the most commonly used scale in clinical assessments of the upper limb.32, 33 Thus, 87.5% of the studies used the Fugl–Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE). The only study that did not use the FMA-UE was the study by Zhang et al.,21 who used the Brunnstrom’s evaluation scale.34 It rates the recovery stage of the upper and lower extremities and hands in levels. The stages are classified from I to VI of recovery, whereby I indicates that the patient has low or absent movement, and VI indicates that the patient can perform voluntary movements.

As can be seen, the reported studies present at least a strong correlation with standard clinical tests. Therefore, the proposed evaluation systems have the potential to support therapists in the objective measurement of the upper limb motor function. Although the meta-analysis found a good relationship between machine learning algorithms and clinical assessment, it also showed a high heterogeneity.

The literature proposes that home-based rehabilitation can offer potential benefits,35, 36, 37 such as performing the exercises according to the patient’s schedule, providing flexibility of location and time, and receiving remote feedback and follow-up by the therapist. The home-based rehabilitation is possible to implement by having motor function evaluation systems, such as those presented in this review.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews in the literature evaluating the correlation between the clinical assessment of the upper limb motor function and machine learning algorithms in post-stroke patients.

Duque et al. conducted a systematic review that included studies focused on evaluating movement analysis in patients with stroke, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and cerebral palsy, as well as in premature infants and the elderly.38 However, their review did not perform the risk of bias assessment or a meta-analysis. Furthermore, it only focused on describing the devices used for data acquisition and the machine learning algorithms.

There are narrative reviews regarding the use of capture sensors and machine learning to perform automated assessments in home-based rehabilitation programs.39 Caramiaux et al. described machine learning models for motor learning and their adaptive capabilities.40 Moon et al. conducted a scoping review to explore the use of artificial neural networks in neurorehabilitation in various pathologies, including stroke, particularly in the prediction of variables such as functional recovery and rehospitalization.41 In the same vein, Sirsat et al. performed a narrative review about the use of machine learning in stroke patients, grouping them according to their use for the identification of associated risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.42 In summary, current reviews studying the application of machine learning in stroke patients focus on its use as a plausible tool for prediction and classification of neurological and motor impairments, as well as the assessment of rehabilitation progress.

Limitations

For more than a decade, the number of publications in basic science and clinical trials has grown exponentially. Clinical trials are considered the best evidence of solving a health problem. Unfortunately, some basic science results are not necessarily reflected in clinical practice.43 Furthermore, several publications have divergent results despite presenting characteristics that superficially seem similar, or they use different variables to measure the impact of the intervention.44, 45 Hence the importance of evidence-based medicine aimed at determining the validity and analyzing the dataset of published studies through systematic reviews.

This systematic review encountered limitations, such as small sample sizes and a risk of bias in the included studies. In addition, the results of the meta-analysis showed high heterogeneity, probably due to the diversity of the statistical tests used in the correlation and different algorithms used in the studies. In addition, this review was limited to analyzing studies focused on the evaluation of the upper limb motor function, so studies analyzing the lower limb motor function were not considered. The exclusion of studies focused on the lower limbs could lead to a limitation, since both limbs have similar ranges of mobility; however, the inclusion of both limbs may have increased the heterogeneity of the review.

Conclusions

The results of the studies included in this systematic review show strong correlations between machine learning algorithms and clinical assessment scores of the upper limb. This correlation indicates a possible application to assist therapists in improving the efficacy of individualized diagnosis of motor function in post-stroke patients. The algorithms also serve as feedback to facilitate the training process for patient rehabilitation. Finally, studies with a representative sample, low risk of bias and better methodological quality are required to reach more robust conclusions.