Abstract

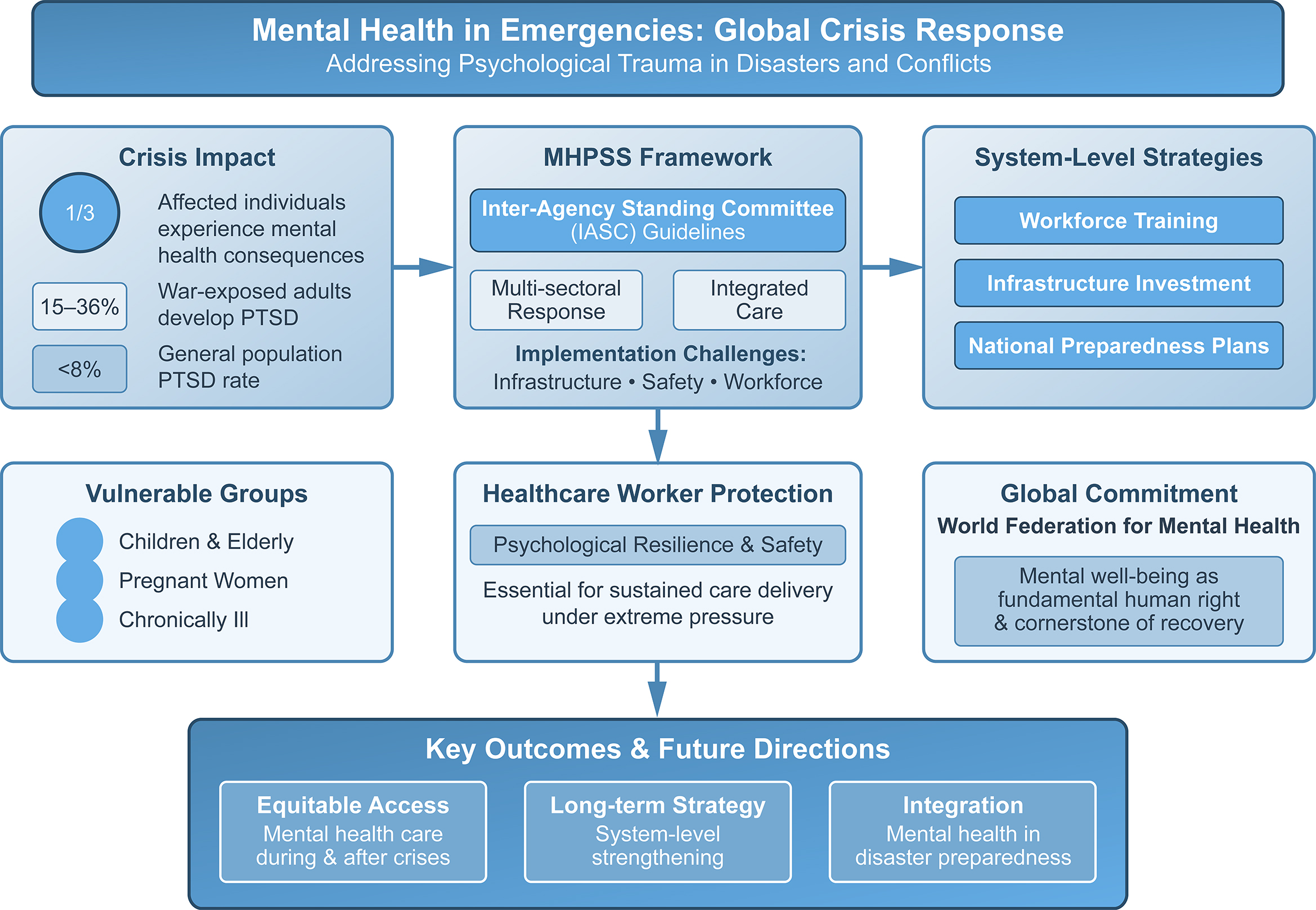

Disasters, wars and health emergencies profoundly affect mental health, with nearly 1/3 of affected populations developing conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression or anxiety, particularly among vulnerable groups like children, the elderly and the chronically ill. Access to mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) is often limited by conflict-related disruptions, stigma or resource shortages, while healthcare workers themselves face immense psychological strain and inadequate protection. Long-term strategies integrating disaster preparedness, mental health services and professional support are essential to safeguard both affected populations and frontline workers during emergencies.

Key words: mental health, catastrophes, access to services, emergencies

Introduction

The term “emergency” is often used interchangeably with “disaster” in global contexts, such as biological and technological hazards, health emergencies, and other crises – a catastrophe or sudden event that causes widespread suffering, hardship, or destruction.1 Millions of people worldwide were and are affected by such events, which profoundly impact both physical and mental health.

Mental health is a state of wellbeing that enables individuals to cope with life’s stresses, realize their abilities, learn and work well, and contribute to their communities. It is an integral component of health and wellbeing, supporting both individual and collective capacity to make decisions, build relationships, and shape the world we live in. Mental health is a fundamental human right for everybody and is essential for personal, community and socioeconomic development.2

The implications of disasters, including armed conflicts, for both civilian and military populations have long been the subject of research.3, 4, 5, 6 In disaster situations, vulnerable groups often experience intense stress, face major challenges and may develop mental disorders. Nearly 1/3 of disaster-affected individuals may suffer significant mental health consequences. While wars, disasters, emergencies, and catastrophes differ in nature, they share many common features.

What these situations have in common is that people often struggle to move on and adapt to change. Particularly vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, individuals who are ill or injured, pregnant women, young children, and infants, are especially dependent on support. Mesa-Vieira et al. documented that younger individuals are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.7

Emergency medicine research has repeatedly emphasized that help and support must effectively reach those in need – and that people must be able to reach support services as well.8 Traumatized individuals, especially those from vulnerable groups, depend on specialized assistance. Access to support always has to do with forms of access and availability, but also with information about it. Outreach support is therefore essential. However, this requires appropriate frameworks to ensure the safety and protection of both helpers and recipients – conditions that are not always guaranteed in emergencies and catastrophes.

Mental health in catastrophes and emergencies

Mental health disorders resulting from disasters and emergencies require specialized skills and effective communication abilities, particularly in trauma-informed care.9, 10 Training and continuing education in this area are essential. Conditions such as PTSD, anxiety disorders, depression, and suicidal ideation are among the most common challenges, while others may experience panic attacks, delusions, or impulsive behaviors.11 Nearly all individuals affected by emergencies experience some form of psychological distress, which, in most cases, tends to improve over time.

However, approx. 1 in 5 people (22%) who have experienced war or conflict within the past 10 years suffer from depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.12 Individuals may experience traumatic losses, and women consistently show higher rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms compared to those without such experiences or to men, across all time points.6, 13

Meta-analyses estimate that approx. 15.3–36.0% of war-affected adult populations experience PTSD, compared to 3.9–7.8% in the general population.5, 14 Other surveys suggest that 26% and 27% of war survivors suffer from PTSD and/or depression, respectively.13 Studies further indicate that factors such as life uncertainty, individual helplessness, and dependence on others or external circumstances can cause significant psychological distress.15

Access and support: Access to services

International guidelines and reports recommend a range of activities and interventions to provide mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) during emergencies – from self-help and community-based support to effective communication, psychological first aid and clinical mental health care. Preparedness and integration with disaster risk reduction are essential to mitigating measurable impacts. Countries can also use emergencies as opportunities to invest in mental health services, leveraging the increased aid and attention they receive to build stronger and more sustainable care systems for the long term.12 Nevertheless, damage to medical and social systems caused by disasters, wars, conflicts, and violence has multiple consequences. For instance, in areas affected by armed conflict, people often cannot access essential services due to ongoing violence, infrastructure destruction, stigma, legal restrictions, financial barriers, or other obstacles.11 Additionally, mental health and psychosocial support professionals remain scarce in conflict settings.16

Mental health care in emergencies often requires “a major rethink.”17 What previously applied may no longer be effective or available. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Group on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings plays a pivotal and active role in promoting mental health care and ensuring access to psychosocial support during conflicts.18 They have developed specific guidelines on MHPSS in emergency settings through an inclusive process involving input from United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental institutions (NGOs) and universities. These guidelines, available in several languages, help plan, establish and coordinate a set of minimum multi-sectoral responses to protect, support and improve people’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing during emergencies.19

Aspects of professionals: Healthcare workers

Zavyalova, an emergency physician, emphasized that being a doctor in wartime means returning home after each shift, wishing the war had never happened and praying for its swift end. People are exhausted – the clients, patients and healthcare workers alike. Yet, as social and medical professionals, they do not have the luxury of fatigue. The clients and patients need the professionals to keep going and they must push through the fatigue to continue delivering the care they deserve.20

The immense need for treatment and counseling, combined with the often-limited number of helpers, places great strain and risk of overload on professionals in these situations. At the same time, it is essential to focus on protecting and supporting these professionals and ensuring that employers conduct proper risk assessments. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has repeatedly emphasized that the failure to protect professionals in war zones is one of the most critical yet frequently overlooked humanitarian issues today.21, 22 As already noted by Javed,11 other factors can exacerbate these challenging conditions. The harmful effects of operating in war zones extend to material and supply shortages, including disruptions in essential services such as electricity, medicines, equipment, water and nutrition, all of which further increase the stress experienced by health professionals.22, 23

Furthermore, the mental health of professionals can be profoundly affected by their work during disasters and catastrophes. Abed Alah emphasized that constant exposure to trauma, combined with the pressure of providing care and counseling under extreme conditions, places an immense burden on the mental wellbeing of professionals, making their situation in conflict zones both critical and often overlooked.24

Conclusions

The effects of war, catastrophes and disasters are varied and multifaceted – for both affected populations and deployed helpers. Ultimately, it is recommended that long-term policies, strategies, and actions be developed to address the medical and psychosocial impacts of conflict, trauma, mental health disorders, and access to support and services.

While national health policies must incorporate disaster management and analysis, priority should also be given to reshaping local, regional, and global structures. This includes emphasizing resource allocation, needs assessment, and strengthening infrastructure to meet requirements, as well as ensuring ongoing evaluation, training and continuing education in this context.11 However, professionals also need protection to ensure access to facilities that support both physical and mental health. The World Federation for Mental Health calls on all responsible parties to safeguard access and strengthen facilities for people affected by catastrophes and emergencies.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.