Abstract

Third-generation cephalosporins have been widely used in clinical practice for many years. Among them, cefotaxime and ceftriaxone are the most commonly administered agents. Despite their nearly identical spectra of antibacterial activity, these antibiotics differ substantially in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. Such dissimilarities may influence the course and outcome of antimicrobial therapy. Furthermore, several additional factors can affect the antimicrobial efficacy of these agents. Cefotaxime and ceftriaxone exhibit markedly different degrees of albumin binding – approx. 25–40% and 95%, respectively. Hypoalbuminemia increases the proportion of the free, pharmacologically active fraction of the drug in the bloodstream; however, it may also lead to prolonged exposure to sub-MIC concentrations. This situation not only reduces the likelihood of therapeutic success but also increases the risk of selecting resistant bacterial strains. Although cefotaxime and ceftriaxone share a similar antibacterial spectrum, antibiotic selection should always be individualized according to the patient’s clinical status and treatment context. A direct comparison of their clinical efficacy undoubtedly warrants further investigation, as suggested by the clear differences in their pharmacokinetic profiles.

Key words: antibiotic therapy, ESBL, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime

Introduction

Third-generation cephalosporins are used for both empirical and targeted treatment of community-acquired infections, but also those associated with hospitalization. As representatives of β-lactam antibiotics, they are characterized by excellent tissue penetration, including the capability to penetrate bones, joints, lungs, middle ear, and cerebrospinal fluid, achieving therapeutic concentrations relatively quickly in these areas. The efficacy of cephalosporins and other β-lactam antibiotics depends on the duration during which the drug concentration remains above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the pathogen (fT > MIC).1 Both in vitro and in vivo animal studies have demonstrated that fT > MIC is the pharmacodynamic parameter that best characterizes antibiotic efficacy, defined as bactericidal activity against the target bacteria.1, 2, 3 Therefore, some β-lactam antibiotics are administered by continuous infusion to optimize their therapeutic effect.

Interesting findings arise from the DALI (Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive Care Patients) study. The authors assessed the therapeutic efficacy of β-lactam antibiotic treatment in patients achieving different levels of fT > MIC, specifically 50% and 100% for the defined endpoint fT > MIC and fT > 4 × MIC. The best therapeutic outcomes were achieved in the group of patients with the highest exposure time to the β-lactam antibiotic.3

The most commonly used third-generation cephalosporins are cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. Susceptibility to ceftriaxone can be inferred based on the sensitivity determined using cefotaxime.4 Despite the nearly overlapping spectrum of antibacterial activity of both antibiotics, there are numerous differences in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles (PK/PD).5, 6, 7 These dissimilarities can affect the course of antimicrobial therapy.8

Pharmacokinetics is the study of a drug’s disposition within the body. It describes the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the drug. In contrast, pharmacodynamics focuses on examining the drug’s effects on the body.

Furthermore, both ceftriaxone and cefotaxime can induce the production of β-lactamases. However, the pharmacokinetic profile and metabolic properties of cefotaxime suggest a lower potential for β-lactamase induction. Serum protein saturation occurs more rapidly with cefotaxime, leading to a faster establishment of equilibrium between albumin and the drug’s free (biologically active) fraction. On the other hand, ceftriaxone has a much more favorable dosing schedule. It has also been reported to favorably modulate the inflammatory response associated with nerve injury. Although both antibiotics share a similar antibacterial spectrum, the choice should be individualized according to the clinical context.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare the pharmacokinetic properties of 2 third-generation cephalosporin antibiotics – ceftriaxone and cefotaxime – and to analyze the potential benefits and limitations of their use based on available literature reports.

Materials and methods

The PubMed and Scopus databases were searched using the keywords: ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, pharmacokinetics, β-lactams, and cephalosporins. The database search took place on November 10, 2024. Moreover, the available drug characteristics of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime were analyzed. Based on the available information, the pharmacokinetic properties of both drugs were compiled. An attempt was made to relate the obtained data to clinical conditions. The topic of this paper was inspired by personal clinical observations. A total of 320 articles published between 1980 and 2024 were reviewed, of which 48 were ultimately included in the analysis. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines were followed.9

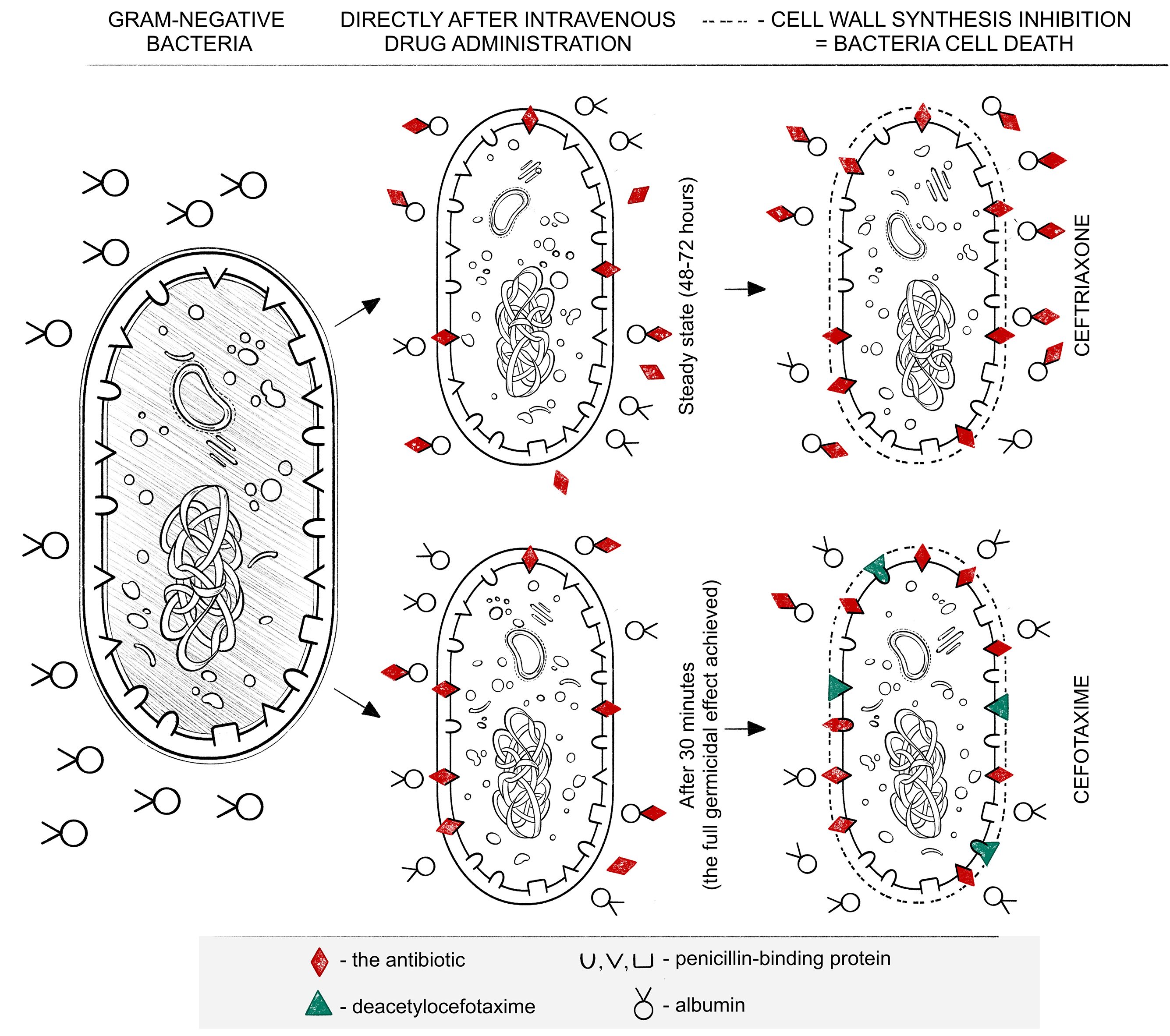

Mechanism of action and dose selection

The mechanism of action of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime involves disrupting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), ultimately leading to cell death. The PBPs are essential for the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. The binding of an antibiotic to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis, thereby preventing the formation of new bacterial cells and exerting a bactericidal effect. This makes cephalosporins, as well as other β-lactam antibiotics, effective against both aerobic Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.1 The dosage regimen of antibiotics is based on their individual PK/PD profile. The greater the affinity for binding to PBPs, the stronger the bactericidal effect of the antibiotic.

Factors affecting the efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics

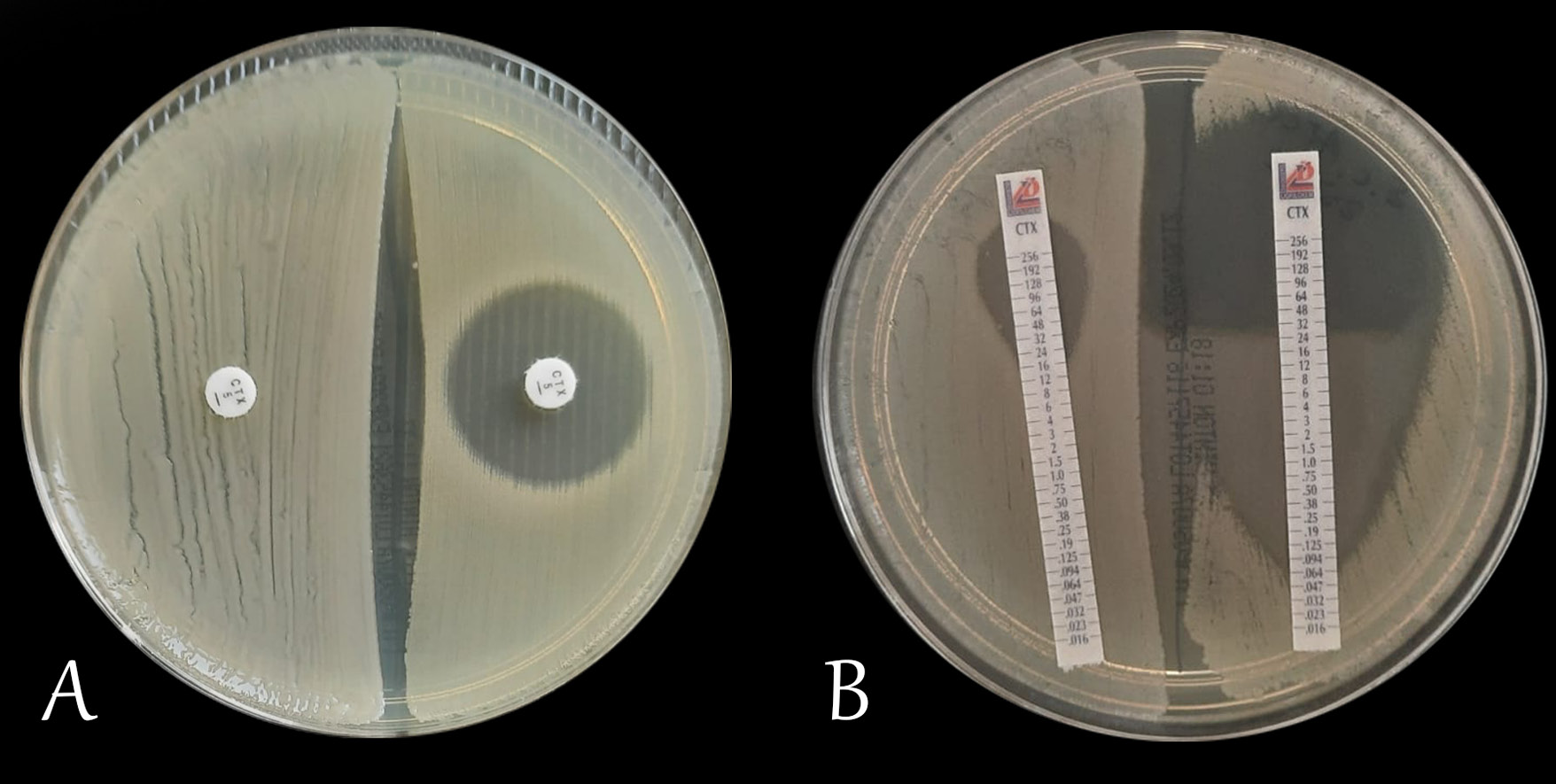

Other indirect factors affecting the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapy include the drug’s pharmacokinetic properties: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Each of these factors determines the extent and manner in which a given antibiotic exerts its pharmacodynamic effect. The effect of an antibiotic on a given microorganism can be assessed in vitro in a microbiological laboratory. One of the most commonly used methods for this purpose is the disk diffusion test on agar medium (Figure 1A). In this method, the result is given as the diameter of the inhibition zone around the antibiotic disk, expressed in millimeters. In another method – the E-test, a gradient strip with the antibiotic is placed on an agar medium inoculated with an appropriate concentration of bacteria. After a suitable time (usually 18–24 h), the inhibition zone is read, which is determined by the apex of the formed parabola (Figure 1B). The interpretation of the read result, depending on the country, is carried out using tools contained in documents of the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI), the French Society for Microbiology (Comité de l’Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie) or the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).10, 11, 12, 13, 14 However, in vitro susceptibility testing alone does not determine clinical success. Achieving it depends critically on the antibiotic’s pharmacokinetic profile – its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion within the body. Thus, pharmacokinetic differences, despite the same in vitro susceptibility, can determine the therapeutic effect. This necessitates individualized dosing that takes into account multiple factors and the specific clinical situation.15, 16, 17, 18

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetics is a discipline within pharmacology that describes the fate of a drug in the body. It plays a crucial role in optimizing and individualizing treatment. Pharmacokinetics describes the journey of a drug in the body, from its release, through absorption, distribution in various tissues, metabolism, and ultimately elimination. Pharmacodynamics, on the other hand, describes the extent to which the drug itself affects the body (its efficacy, potency, occurrence of adverse effects, interactions, etc.). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties are detailed in the summary of product characteristics. However, many clinical scenarios significantly influence the pharmacodynamic characteristics of a drug through its pharmacokinetic fate.

Absorption encompasses all processes leading to the drug’s entry into the circulatory system, thereby reducing its concentration at the site of administration. Distribution, in turn, refers to the transfer of the drug from the bloodstream into tissues, which may occur through either active or passive transport. Metabolism includes all biochemical processes the drug undergoes, ultimately enhancing its physicochemical properties to facilitate excretion via the appropriate organ. The drug elimination process depends, among other factors, on its degree of binding to plasma proteins. The higher the degree of a drug bound to plasma proteins, the slower its elimination process tends to be.

There are many terms associated with drug pharmacokinetics that define it. The most important ones include: volume of distribution (Vd), clearance (Cl) and half-life (t1/2). Volume of distribution (Vd) is the ratio of the measured concentration of the drug, usually in serum (C), to the total amount of the drug in the body (X): Vd = X/C. The more strongly the drug binds to tissue proteins and the lower its concentration in plasma, the greater its volume of distribution. Half-life (t1/2) is the time it takes for the concentration of the substance to decrease by half from its initial value.19

Clearance (Cl) is defined as the rate at which a drug is eliminated from the body and is closely related to the blood flow rate through the excretory organ (Q) and dependent on the extraction ratio (ε). The extraction ratio numerically expresses the difference in drug concentration entering and leaving the organ. The amount of drug entering the organ is considered as 1, so the extraction ratio ranges from 0 to 1, where a value of 0 indicates no drug elimination in the organ, and 1 indicates 100% elimination of the drug from the organ. Blood flow through organs can vary in many clinical conditions. Clearance, and thus the elimination rate, will also vary according to the equation Cl = Q x ε. It is important to note that ceftriaxone and cefotaxime differ in their extraction ratios, which additionally affects drug clearance.

The high degree of albumin binding slows the elimination of the antibiotic from the body (Table 1).4, 6, 20, 21 This occurs through slower metabolism, as well as reduced glomerular filtration. The binding of the antibiotic to albumin is not permanent and leads to the establishment of an equilibrium level. This is crucial for antimicrobial therapy, as this level must exceed the MIC of the bacteria (up to 4 times in critical conditions). While part of the active form is metabolized to balance the albumin/drug free fraction, another part of the drug is released from its non-permanent binding to albumin. It undergoes further transformations but can already exert a lethal effect on bacteria. The release of the drug from its binding to plasma proteins helps maintain its plasma concentration after the unbound fraction has already undergone metabolism and/or elimination. Over time, between successive doses of β-lactam antibiotics, the albumin-to-drug ratio changes, leading to a reduction in the free (unbound) drug fraction. These interactions follow the principles of the law of mass action (Guldberg and Waage’s law). The degree of albumin binding, as well as other distribution and metabolic parameters, varies among antibiotics.22, 23, 24, 25

Ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone binds to albumin at approx. 95%, with the unbound fraction showing biological activity. The high degree of binding affects the rate of antibiotic elimination, significantly slowing it down. Subsequent doses significantly increase the average maximum serum drug concentration by approx. 11% (8–15%), resulting in the steady state being reached relatively late, around 48–72 h after the first dose of the drug. Although hypoalbuminemia increases the free, pharmacologically active fraction of the drug in the bloodstream, it also raises the risk of prolonged exposure to sub-MIC concentrations due to the establishment of equilibrium between bound and unbound fractions at an insufficient level. This situation not only reduces the likelihood of therapeutic success but also promotes the selection of resistant bacterial strains.1, 7, 23

Both ceftriaxone and cefotaxime can be administered intravenously or intramuscularly. Currently, there are several dosing regimens for ceftriaxone administered intravenously (2 g × 1, 2 g × 2, 4 g × 1). It is particularly important to use maximum daily doses (4 g) in the treatment of bacterial meningitis to achieve the penetration of the drug into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In patients without meningitis, the concentration of ceftriaxone in the CSF is only 2% of the serum concentration. However, in cases of meningitis, it increases more than twelvefold, reaching 25% of the serum concentration. The highest concentration of the drug in the CSF occurs approx. 4–6 h after intravenous administration of the drug.4 In critically ill patients (with dysfunction of more than 1 organ/system in the course of sepsis or those diagnosed with septic shock based on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA) and/or the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to achieve a better therapeutic effect, it may be necessary to maintain ceftriaxone concentration in the serum >4 × MIC of the pathogen. Improved PK/PD outcomes – reflecting enhanced therapeutic efficacy through optimized dosing strategies – can be achieved by modifying the mode and frequency of drug administration. Some authors recommend continuous infusion, and it has also been demonstrated that administering ceftriaxone every 12 h results in superior PK/PD effects compared with a 24-h dosing regimen.1, 7, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

There is a risk of calcium salt precipitation during intravenous ceftriaxone therapy. The occurrence of deposits in the gallbladder and kidneys, as well as cases of pancreatitis, has been reported. Fatal outcomes have also been documented in premature infants and neonates receiving ceftriaxone, attributed to co-precipitation with calcium in the kidneys and lungs. For this reason, there is a restriction on using ceftriaxone concurrently with calcium-containing preparations, including parenteral nutrition solutions, certain crystalloids, and during continuous renal replacement therapy with citrate anticoagulation, where continuous calcium solution supplementation is required. In cases of septic shock, balanced crystalloid resuscitation is required, often involving fluids that contain calcium. Given the prolonged time required for ceftriaxone to reach its peak serum concentration, it may be advisable to use an alternative antibiotic with a more favorable PK/PD profile. In septic shock, the delay in initiating appropriate antibiotic therapy is associated with increased mortality.1, 14, 29, 30, 31, 32 This should be kept in mind when choosing an antimicrobial agent.

The study by Lim et al. provides valuable data. The authors analyzed 939 patients who received ceftriaxone in the emergency department for sepsis or septic shock. The study compared the impact of the drug administration mode (3 min vs 30 min) on mortality. No statistically significant differences in mortality were observed between the 2 groups. As the effectiveness of β-lactam antibiotics depends on the duration of drug exposure (fT > MIC), the observed findings may be explained by the pharmacokinetic properties of ceftriaxone. A similar study involving cefotaxime would certainly be of interest.33 The available literature still lacks sufficient studies comparing these 2 antibiotics.

Cefotaxime

Cefotaxime binds to albumin to a much lesser extent than ceftriaxone, i.e., in the range of 25–40%. Cefotaxime is the only third-generation cephalosporin that, as a result of metabolism, is partially (1/3 of the dose) transformed into desacetylcefotaxime and lactone. While the lactone itself does not exhibit biological activity, deacetylcefotaxime does, reaching concentrations in tissues and body fluids that inhibit bacterial growth. Moreover, desacetylcefotaxime, despite its lower biological activity compared to cefotaxime, exhibits greater resistance to β-lactamases, which can be an additional advantage. The half-life of cefotaxime ranges from 50 min to 80 min, while for desacetylcefotaxime, this time extends to 125 min. This necessitates more frequent administration of this antibiotic, i.e., 1–2 g × 3, and in the case of bacterial meningitis, 2 g × 4. Similar to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime penetrates the blood–brain barrier much better in meningitis and reaches therapeutic concentrations there.34

After intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone at a dose of 1–2 g, the maximum serum concentration is reached after approx. 2–3 h, whereas the time for 1 g of cefotaxime is 30 min. The dosing frequency of both antibiotics is influenced by differences in serum clearance, which is respectively 10–22 mL/min for ceftriaxone and 260–390 mL/min for cefotaxime, and from a clinical standpoint, is more favorable for ceftriaxone. Additionally, the less frequent need for administering the drug is associated with a lower risk of infection related to the drug administration itself. On the other hand, cefotaxime exhibits a more favorable volume of distribution, in the range of 21–37 L, whereas for ceftriaxone, it falls within the range of 7–12 L. Unlike ceftriaxone, cefotaxime is removed during hemodialysis, which should be taken into account when dosing this drug in patients undergoing such procedures. Dose adjustment of both antibiotics applies only to cases of end-stage renal failure (stage V chronic kidney disease). It involves halving the dose, not the frequency of its administration.1, 5, 6, 35, 36, 37

The influence of PK/PD on the development of resistance mechanisms

Differences in PK/PD can also influence the promotion of mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. This is associated with a change in the exposure time to bactericidal concentrations of the antibiotic. The longer the time below the MIC of bacteria, the greater the likelihood of inducing antibiotic resistance. One example of such resistance, involving the production of enzymes that deactivate antibiotics, is the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs).38 This mechanism plays a significant role in the therapy of many invasive infections because the detection of ESBL significantly narrows therapeutic options. It has also been found that carriage of bacteria strains producing ESBL can persist for months.39 Moreover, the presence of ESBL-producing microorganisms is also associated with increased transmission of other antibiotic resistance mechanisms.40 There are numerous data confirming the phenomenon of ESBL production after the use of third-generation cephalosporins.41, 42 The choice of cefotaxime may be associated with a lower risk of β-lactamase production. First, this is associated with potentially shorter exposure times below the MIC of bacteria. Second, the metabolite of cefotaxime, desacetylcefotaxime, has a significantly longer half-life than the parent compound, exhibits biological activity, and has documented greater resistance to the action of β-lactamases.

Interaction between drugs

Information about selected interactions between ceftriaxone and cefotaxime with other drugs is shown in Table 2.43, 44

Limitations

The study is limited by the relatively small number of publications comparing treatment outcomes using cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. Another limitation is the more frequent use of ceftriaxone compared to cefotaxime in non-pediatric patients. The lack of widespread availability of therapeutic concentration measurements for β-lactam antibiotics in patient serum significantly restricts the ability to monitor ceftriaxone and cefotaxime levels. This limitation hinders the conduct of multicenter studies in this area and, consequently, reduces the number of scientific reports on the subject.

Conclusions and perspectives

Due to pharmacokinetic differences, it appears that despite the established principle of extrapolating susceptibility results from one antibiotic to the other in infections caused by Gram-negative bacilli, there are scenarios where the choice between ceftriaxone and cefotaxime may significantly impact treatment outcomes and the initial response to antimicrobial therapy. Insights into the pharmacokinetics of these antibiotics suggest a variable response to the implemented antibiotic therapy, particularly in critically ill patients. The pharmacokinetic properties of these antibiotics may also affect the development of resistance mechanisms, including the production of β-lactamases, among Gram-negative bacilli.

Both ceftriaxone and cefotaxime are commonly used antibiotics in the treatment of invasive infections as targeted antibiotic therapy, but they are also utilized in numerous empirical therapy regimens. Both drugs exhibit a very good PK/PD profile and a virtually identical spectrum of antimicrobial activity. They penetrate very well into most body fluids and tissues, which makes them widely applicable. However, the differences between the 2 drugs mean that their use should be individually considered each time and adjusted not only to the patient’s condition but also to the clinical situation. From a clinical point of view, the onset of antibiotic action is important. While in most infections, both ceftriaxone and cefotaxime will have sufficient time to achieve appropriate concentrations at the site of infection, in special situations such as septic shock or severe cases of meningitis, the differences can be significant.23 In such cases, the use of cefotaxime should theoretically be preferable. However, it should also be noted that in the treatment of Lyme disease, ceftriaxone is the antibiotic of choice, and for such situations, the possibility of reducing the frequency of drug injections seems justified. It has also been shown that ceftriaxone has a beneficial effect on modulating glutamate neurotransmission, reducing the inflammation-related nerve response.45, 46, 47 Comparison of the clinical efficacy of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime undoubtedly requires further research, as indicated by their pharmacokinetic profiles. Currently, ceftriaxone is the most commonly chosen cephalosporin for empirical treatment.48, 49 However, there is a real risk of initially lower effectiveness in such a choice, which may also more frequently lead in such cases to antibiotic switching to a broader-spectrum agent, such as carbapenem. In the era of rapidly increasing antibiotic resistance and the spread of Gram-negative rods producing β-lactamases (including carbapenemases), the carbapenem-sparing strategy plays a crucial role. Clinical observation and further research are required to compare the frequency of introduction of ESBL production by ceftriaxone and cefotaxime.

Furthermore, both ceftriaxone and cefotaxime can induce the production of β-lactamases. The pharmacokinetic profile and metabolism of cefotaxime support a lower risk of production of such enzymes. Serum protein saturation occurs much more rapidly with cefotaxime, leading to a quicker establishment of the equilibrium state between albumin and the drug’s free (biologically active) fraction. On the other hand, ceftriaxone has a much more favorable dosing schedule. It is also credited with favorably modulating the inflammatory response associated with nerve damage. Despite the similar antibacterial spectrum of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime, the choice of antibiotic for therapy should always be carefully evaluated on an individual basis.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.