Abstract

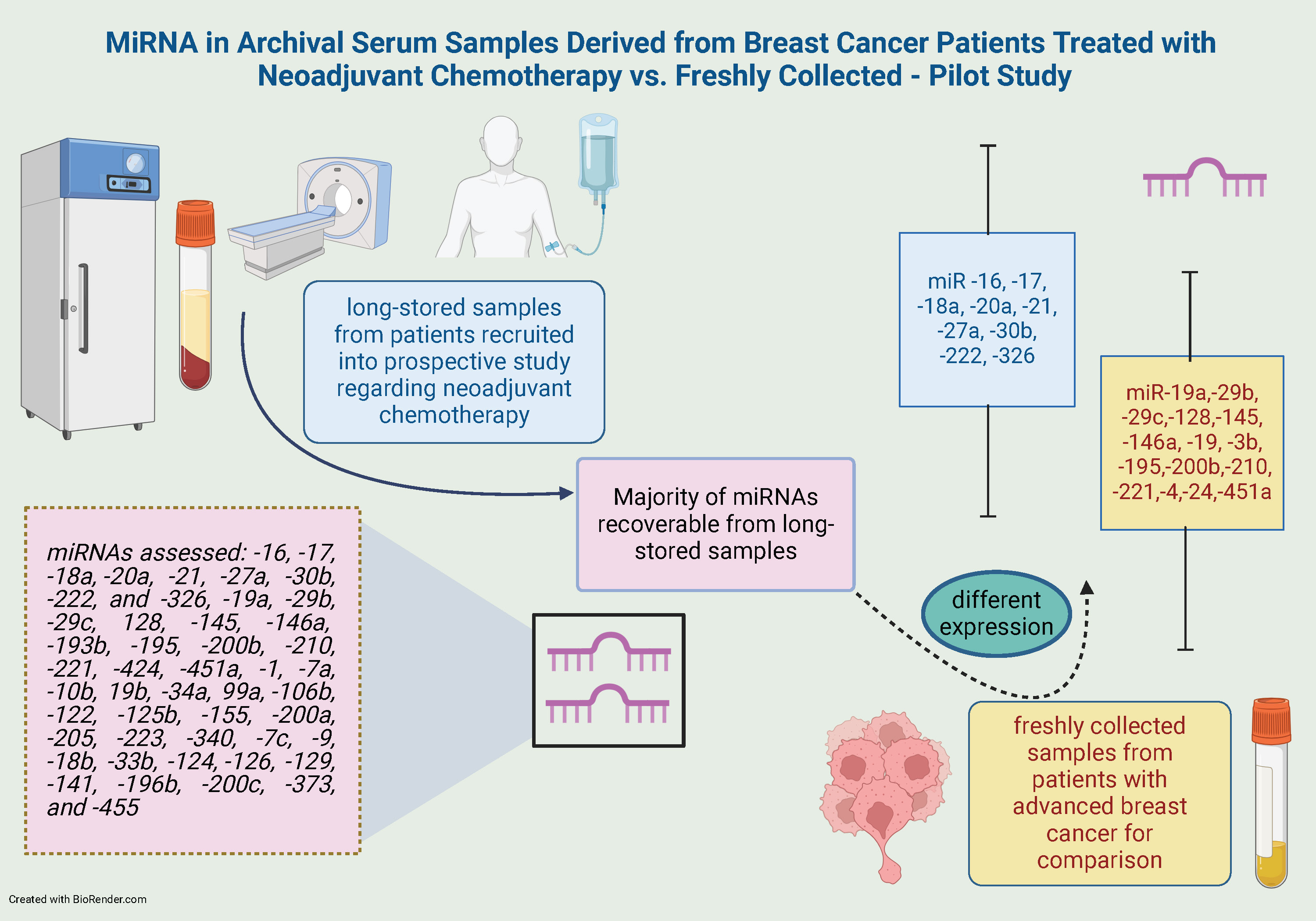

Background. Liquid biopsy, including miRNA profiling, is a promising approach to identify breast cancer (BC) resistance. However, the effect of long-term storage on the quality of miRNA assessment in archival serum has not been fully addressed.

Objectives. We aimed to determine whether miRNAs were recoverable from long-stored serum samples to subsequently evaluate prognostic and predictive miRNA value in the archival collection of samples from patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy at Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Gliwice, Poland.

Material and methods. We have evaluated miRNA quantity in serum samples stored for up to 12 years. Additionally, we compared miRNA expression in archival samples to freshly collected samples derived from advanced BC patients.

Results. Forty BC patients were included in the study. Archival samples were derived from 20 BC patients treated with radical intent between 2011 and 2015. Freshly collected samples were collected from 20 advanced BC patients in 2022. miRNA was present in archived serum samples frozen at –80C° for at least 12 years. Additionally, we found significantly different expressions between the 2 analyzed groups. Expression of circulating miR-16, -17, -18a, -20a, -21, -27a, -30b, -222, and -326 were significantly higher in archival samples, whereas expression of circulating miR-19a, -29b, -29c, -128, -145, -146a, -193b, -195, -200b, -210, -221, -424, and -451a were lower than in freshly collected samples. In 14 miRs, we observed expression in both groups; however, differences were statistically insignificant (miR-1, -7a, -10b, -19b, -34a, -99a, -106b, -122, -125b, -155, -200a, -205, -223, -340).

Conclusions. MiRNA can be identified from long-stored samples, making large prospectively collected serum repositories with long follow-up time an invaluable source for miRNA biomarker discovery.

Key words: breast cancer, biomarkers, liquid biopsy, miRNA, archival samples

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer globally.1 Early detection intensifies the effort toward discovering new biomarkers that can improve its prognosis and therapeutic outcomes. Numerous systemic treatment approaches for BC are still in their early phases of development; thus, it is essential to find precise biomarkers that may be used to guide therapeutic decisions regarding cytotoxic agents, targeted therapies and immunotherapy.2

Substantial advances in molecular signalling processes have lead to a discovery of a variability of biomarkers in tissues and blood (liquid biopsy) that may help predict the probability of cancer spread, treatment efficacy and tolerance.2 Tumor cells are heterogeneous; therefore, a single biomarker is not precise enough to effectively diagnose cancer progression and metastasis, and a combination of biomarkers is preferred. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers are 2 categories of biomarkers that indicate likely clinical outcomes and treatment efficacy. MicroRNA (miRNA) can be utilized in both of these applications.3

The miRNAs are short non-coding RNA molecules containing about 22 nucleotides. To date, 48,860 have been identified, including 2,654 mature sequences in the human genome.4 More than half of human protein-coding genes are regulated by miRNAs.5 They act as tumor suppressors or oncogenes, and functional studies have proven that miRNA dysregulation is causal in numerous cancer cases.6 Expanded insights into the roles of miRNA dysregulation in development and cancer progression have made miRNAs attractive tools and targets for new treatment approaches.6 They can be found both in tissue and blood, allowing the utilization of liquid biopsy, which is a useful clinical technique.7

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has an essential role in the prevention of BC recurrence. However, the primary obstacle is drug resistance. The miRNA profiling is the prominent approach to identifying BC resistance. Expression of several miRNAs was decreased in chemotherapy resistance. In cells derived from triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients treated with neoadjuvant paclitaxel, elevated expression of miR-18a increased paclitaxel resistance.8 MiR-90b, -130a, -200b, and -452 may lead to chemoresistance by regulating drug-related cellular pathways.9 Responders to neoadjuvant chemotherapy had significantly lower levels of miR-21 and miR-195 than non-responders.10 Serum miR-125b also predicted poor chemotherapy outcomes and shorter disease-free survival (DFS).11 MiR-34a has recently emerged as a tumor suppressor of significant interest. Liu et al. found that changes in serum miR34a expression were associated with treatment response and DFS.12 In a small group of 27 patients, serum miR-451 was higher and showed a significant gradual decline during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, consisting of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and taxane, in the patients stratified as clinical responders.13 The increase of serum expressions of both miR-19a and miR-205 during neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisting of doxorubicin and paclitaxel in patients with luminal A BC was more pronounced in the resistant group compared with the sensitive group. Furthermore, both were independent predictive factors for chemotherapy response.14 The downregulation of serum miR-99a expression in BC patients has been closely associated with a poor prognosis.15 The expression of miR-10b, -21, -34a, -125b, -145, -155, and -373 in patients before the start of treatment was significantly higher, and miR-210 was lower than levels in healthy controls.16 A summary of studies on circulating miRs in BC patients is presented in Table 1.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41

Objectives

We aimed to determine whether miRNAs were recoverable from long-stored serum samples. To achieve this, we assessed serum samples from 20 BC patients, drawn at various time points. Additionally, we compared them to miRNA expression from freshly collected samples derived from the group of patients with advanced BC.

Materials and methods

Study population

Archival serum samples were taken from the patients with BC recruited into prospective observational clinical trial concerning neoadjuvant chemotherapy. All patients had serial blood collection before the beginning of the treatment and during systemic treatment. For the purpose of this pilot study, only samples collected at the beginning of the treatment were used. These samples were taken between 2011 and 2015. A tumor biopsy at Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology (Gliwice, Poland) was performed for histopathological verification and the possibility of further molecular assessment. Moreover, patients underwent multimodality treatment (systemic treatment including chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, surgery, and radiation therapy) at our institution and remained in follow-up. Furthermore, extensive radiologic evaluation was performed, including baseline and serial breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) assessment, baseline 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT), and assessment of early metabolic response after the 1st cycle of chemotherapy. Freshly collected samples were taken from the group of patients with advanced BC.

Clinical samples

Blood processing and sample storage

All laboratory procedures were performed at Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology in the Department of Clinical and Molecular Genetics. All clinical samples described here were obtained from subjects with informed consent. Freshly collected samples comprised plasma. Blood was processed for plasma isolation within 1 h of collection. Blood was centrifuged in cfRNA collection tubes (RNA Complete BCT® CE; Streck LLC, La Vista, USA) at 1,800 × g at room temperature in an Eppendorf 5810R (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) for 15 min. Plasma was transferred to a fresh tube and centrifuged at 2,800 × g for 15 min. Plasma was aliquoted, with inversion to mix between each aliquot, and stored at –80°C. Archival samples comprised serum samples. For serum collection, blood was collected into BD Vacutainer® serum tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA) and allowed to clot for 30–60 min at room temperature. Clot was removed by centrifugation at 1,300 × g at room temperature for 10 min. Serum was aliquoted and stored at –80°C until miRNA isolation.

MiRNA isolation and measurement of miRNA expression

MiRNA isolation was performed with the TaqMan® miRNA ABC (Anti-miRNA Bead Capture) Purification Kit – Human Panel A (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA). Complementary DNA (CDNA) template from miRNA was prepared with the TaqMan® Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Mature miRNAs from total RNA were modified by extending the 3’ end of the mature transcript through poly(A) addition, and then the 5’ end was lengthened by the 5’ end by adaptor ligation. The modified miRNAs were then subjected to universal reverse transcription followed by amplification to increase uniformly the amount of cDNA for all miRNAs (miR-Amp reaction). Analysis of miRNA expression was performed with TaqMan® Advanced miRNA Assays. The assays can detect and quantify the mature form of the miRNA from 2 μL of total RNA from serum or plasma. TaqMan® Fast Advanced Master Mix was used to prepare PCR Reaction Mix. Customizable TaqMan® Advanced MicroRNA Cards (ADV MIRNA CARD FRMT 48; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) were used to measure expression. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was carried out on a QantStudio 12K FLEX (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) with a TaqMan® Array Micro Fluidic Thermal Cycling Block. Nucleic acid-free pipette tips were used to handle all reagents. All procedures were performed following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Based on published literature, 48 miRNAs were selected for expression measurement: miR-16, -17, -18a, -20a, -21, -27a, -30b, -222, and -326, -19a, -29b, -29c, 128, -145, -146a, -193b, -195, -200b, -210, -221, -424, -451a, -1, -7a, -10b, 19b, -34a, 99a, -106b, -122, -125b, -155, -200a, -205, -223, -340, -7c, -9, -18b, -33b, -124, -126, -129, -141, -196b, -200c, -373, and -455.

Response assessment

The early metabolic response to treatment in (18F-FDG-PET/CT) was assessed based on the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) guidelines.42 Specifically, complete metabolic response was defined as a complete resolution of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in all sites, partial metabolic response referred to a reduction of at least 25% in maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), an increase or decrease of less than 25% in SUVmax indicated stable metabolic disease, whereas progressive metabolic disease was defined as either a >25% increase in SUVmax or the development of a new FDG-avid lesion.

Tumor response in MRI was assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) v. 1.1, categorizing outcomes as a complete response, partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease.43

Statistical analyses

Continuous data were summarized as median values and presented with an interquartile range (IQR; Q1–Q3). Wilcoxon rank sum test evaluated differences between the 2 groups. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was used as an adjustment for multiple testing. To assess the normality of the data, the Shapiro–Wilk test was employed. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All computational analyses were performed in the R environment for statistical computing v. 4.0.1, “See Things Now,” released on June 6, 2020 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org, accessed December 20, 2022).

Results

Archival samples were derived from BC patients treated with radical intent between 2011 and 2015, including 6 in 2011, 4 in 2012, 2 in 2014, and 8 in 2015. Half of the patients were premenopausal. Seventeen patients were diagnosed with early BC. In contrast, 3 patients were diagnosed with oligometastatic disease and were included in treatment with radical intent by the multidisciplinary team. Five patients received the AC-P regimen (AC – doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel), 2 patients AC regimen, 7 patients TAC regimen (docetaxel, AC), 3 patients TEC regimen (docetaxel, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide), 2 patients FEC regimen (fluorouracil, AC), and 1 patient the AT regimen (doxorubicin plus docetaxel). All patients with archival samples underwent baseline positron emission tomography / computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning and MRI imaging. The majority of patients (13, 65%) had early metabolic assessment after the 1st chemotherapy cycle. For this subroup, the median decrease in SUVmax following the 1st chemotherapy cycle was 28% (IQR: 13.0–60.5). Specifically, a partial metabolic response was observed in 69% of patients (9 of 13), while 31% had stable metabolic disease (4 of 13 patients). Serial MRI assessments were conducted for all patients except 1. Seventeen patients (89%) achieved partial remission on MRI. Stable disease was observed in 2 patients (11%). Sixteen patients underwent subsequent surgery. In 2 patients, complete histopathologic remission was observed (12.5%). All of the analyzed patients experienced disease recurrence. The median DFS was 31.2 months (5.8–72.3 months). Fresh samples were derived from advanced BC patients in 2022. Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 2.

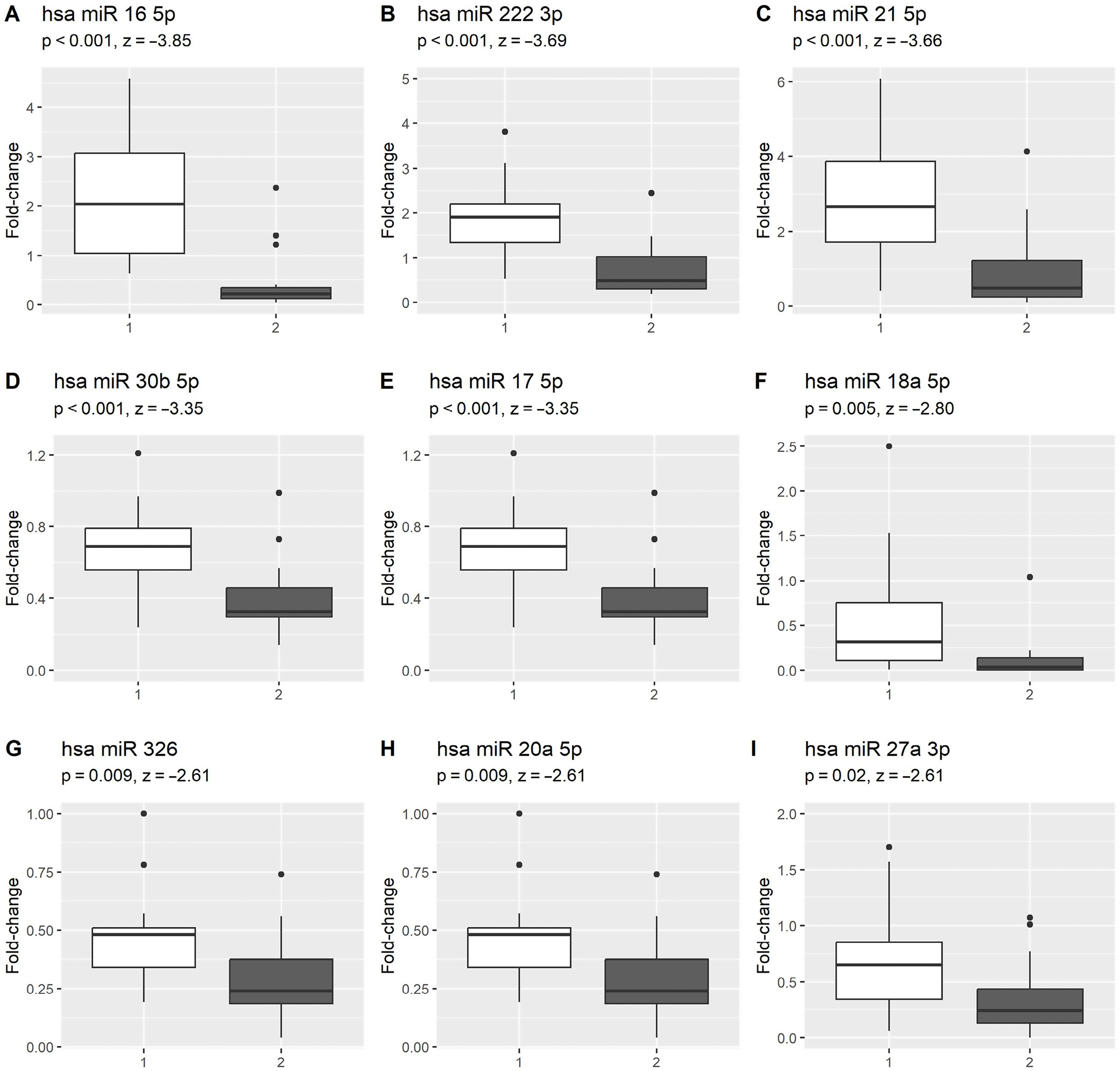

In all but 1 archival sample, miRNA expression was detected. The expression of circulating miR-16, -17, -18a, -20a, -21, -27a, -30b, -222, and -326 was significantly higher in archival samples than in freshly collected samples. The results are depicted in Figure 1. Specifically, miR-17 exhibited higher expression in patients treated with radical intent. Among this group, the vast majority received taxane-containing chemotherapy regimens (16 patients, 80%), including 11 patients treated with docetaxel and 5 patients treated with paclitaxel.

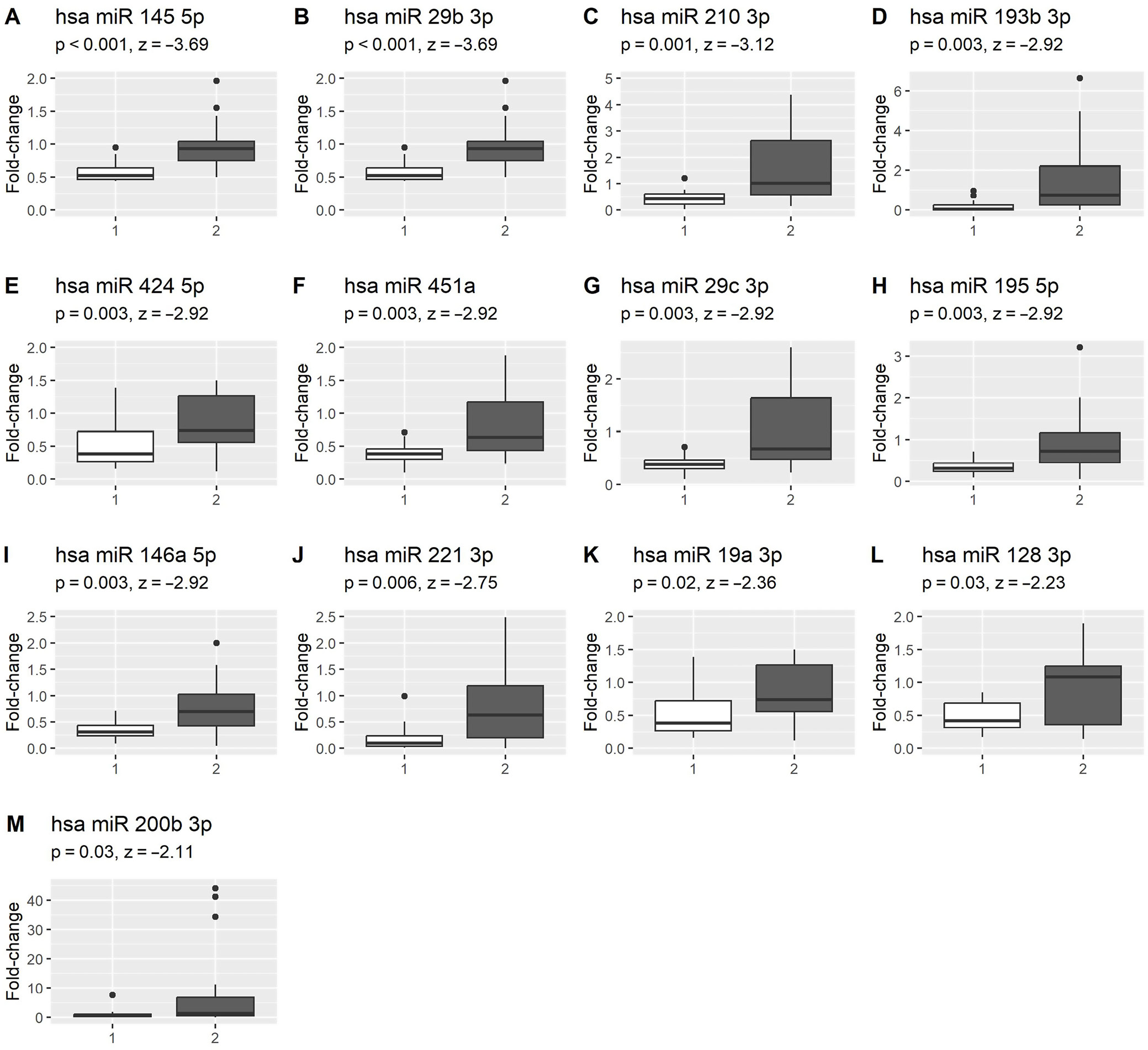

The expression of circulating miR-19a, -29b, -29c, 128, -145, -146a, -193b, -195, -200b, -210, -221, -424, and -451a was lower in archival samples than in freshly collected samples. These results are depicted in Figure 2.

In 14 miRs, we observed expression in archival samples and freshly collected samples; however, differences between the groups were statistically insignificant (miR-1, -7a, -10b, 19b, -34a, 99a, -106b, -122, -125b, -155, -200a, -205, -223, and -340). Finally, no expression of the remaining 12 miRs was observed (miR-7c, -9, -18b, -33b, -124, -126, -129, -141, -196b, -200c, -373, and -455). Results of the normality tests are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion

Levels of specific circulating microRNAs in BC patients are associated with tumor development and progression and may be involved in chemotherapy resistance. Moreover, the dynamics of circulating microRNAs might serve as a novel biomarker of clinical response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Our study’s archival samples were derived mostly from early BC, except for 3 patients with the oligometastatic disease treated with radical intent. Freshly collected samples included those obtained from BC patients. That would be the primary explanation for different expressions of miR-16, -17, -18a, -20a, -21, -27a, -30b, -222, -326, -19a, -29b, -29c, -128, -145, -146a, -193b, -195, -200b, -210, -221, -424, and -451a.

Serum miR-21 expression could predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.11 In our study, the expression of miR-21 was higher in archival samples, comprising mostly patients with early BC, compared to fresh samples collected from patients with advanced disease. However, it is worth pointing out that not only baseline expression is important, but also the dynamic changes during treatment. Lowering serum miR-21 expression could predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy as early as the end of the 2nd treatment cycle. Furthermore, patients with decreasing miR-21 expression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy had better DFS than those showing increased ser-miR-21 expression. In another study, changes in ser-miR-21 levels during neoadjuvant chemotherapy were correlated with clinical response and survival; however, it was not associated with pathology response.16

In BC tissues and cells resistant to taxol, the increased expression of nuclear receptor co-activator 3 (NCOA3) results in downregulation of miR-17. Thus, NCOA3 and miR-17 may serve as a biomarkers and a therapeutic targets in BC resistance to taxol.44 By directly targeting NCOA3, miR-17 enhanced the sensitivity of BC cells to taxol, implying a potential tumor-suppressor role for miR-17 in BC.44

In our study, higher levels of miR-17 were observed in a population undergoing taxol-containing chemotherapy. Thus, further analysis of our group with miRNA assessment in serially collected samples would be interesting to verify this hypothesis on a liquid biopsy level. Moreover, blood-derived data suggested a potential association between miR-17, -19b and -30b expression levels and complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy,25 and miR-30b was another overexpressed miRNA in our study.

Elevated circulating levels of miR-195, in contrast to other miRs (such as let-7a, miR-10b and miR-155), were found to be specific for BC.36 Furthermore, systemic miR-195 levels showed incremental increase with larger breast tumors.36 In BC patients, circulating miR-195 was significantly higher compared to control patients.36 In contrast, some studies showed lower levels of miR-195 in BC patients than in healthy control,37 or no significant differences in blood serum expression values of miR-195 between these 2 groups.20 Interestingly, in luminal A BC, miR-195 was found to be underexpressed in patients with metastatic disease compared to patients with local disease.38 In our study, which predominantly included patients with luminal B BC, we observed higher miR-195 expression in patients with metastatic disease. To fully understand miR-195 dynamics, further evaluation involving a larger cohort of patients is necessary. This assessment should explore differences in miR-195 expression between subtypes and investigate its predictive value during neoadjuvant treatment.37

Levels of circulating miR-373 were significantly higher in TNBC patients.45 In our study, which was comprised of only luminal cases, we did not observe miR-373 expression in archival or freshly collected samples.

Serum miR-222 predicted both efficacy and trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity.40 Furthermore, miR-222, -20a and -451 level changes were associated with chemosensitivity, whereas a chemo-induced decrease in plasma miR-34a in the insensitive patients was found.46 We found higher levels of miR-222 and miR-20a in a population undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy; levels of miR-451 were lower, whereas miR-34a was comparable to those observed in advanced BC patients. Since we have toxicity data in our population, we would like to further evaluate the potential of miR-222 in cardiotoxicity prediction.

Few studies have been performed to verify the predictive potential of circulating miRNAs in BC. MiR-125b was correlated with resistance to chemotherapy,31 whereas downregulation of miR-155 suggested treatment response.35 Our study found similar serum expression of miR-125b and miR-155 in archival samples, derived mostly from early BC patients and freshly collected samples from advanced BC patients. The expression of plasma miR-122 was found to be significantly upregulated in BC patients compared to healthy controls.30 In our study, no significant differences were found between patients with early-stage and advanced-stage BC. Nonetheless, miR-122 dysregulation may be involved in response to chemotherapy, radiotherapy and BC progression.47

Despite the advantages associated with miRNA evaluation as potential blood-based biomarkers, reproducible and robust miRNA quantification is challenging, and attention must be paid to the numerous technological parts of the measurements. Recently published reviews have comprehensively discussed the challenges and difficulties in accurately quantifying miRNAs, comprising pre-analytical, analytical and methodological issues contributing to result heterogeneity.48 During the preanalytical phase, meticulous attention to practical details is crucial. We emphasized the importance of collecting an adequate blood volume. This includes ensuring an appropriate ratio to anticoagulant. Ensuring timely processing of samples for subsequent steps was a priority. In order to minimize transport time, we prepared the sample for processing before blood sampling. During blood draw, we took great care to prevent hemolysis, which could affect sample integrity. Our stored materials adhered strictly to appropriate conditions, avoiding any individual deviations.

Moving on to the analytic phase, we maintained a meticulous approach. Two individuals independently verified probe identification numbers. We followed manufacturer guidelines meticulously throughout the process. Our methodology was tailored to meet the expectations and requirements of the source material, which comprised both plasma and serum.

Heterogeneity may result from various situations. For instance, adequate probe rotation within the center, from the moment of blood draw to the time of analysis, plays a crucial role. While this procedure is not always feasible for every center, we were fortunate to perform all procedures within 1 building. Additionally, using specialized probes and preparing experiments specifically for the material contributed positively to our study.

Remarkably stable form is an essential prerequisite for utility as a biomarker.49 The miRNA molecules are robust and survive harsh treatment and storage conditions.48 Incubation of plasma at room temperature for up to 24 h or subjecting it to 8 freeze–thaw cycles appears to have minimal impact on the levels of specific miRNAs.49

Another issue is the type of blood derivative. Serum has less baseline platelet contamination than plasma, while the differential release of confounding miRNAs by blood cells may be associated with clot formation.50 Measurements of selected miRNAs obtained from the matched samples of plasma or serum collected from a given individual at the same blood draw were strongly correlated, showing that both plasma and serum samples are suitable for miRNAs investigation as blood-based biomarkers.49 However, studies have yielded conflicting results as to which type of sample is superior to the other.51 MiRNA was found to be potentially recoverable from plasma samples stored for more than 12 years.52 It showed high stability and long frozen half-life in plasma samples stored for 14 years.53 On the contrary, despite storage at –80°C, miRNA levels were significantly changed in whole blood samples in long-term storage, defined as 9 months.54 Our repository, like many others, contains a greater number of clinical serum specimens than plasma samples. Thus, our results may enable further research of archival samples.

As we validated the identification of miRNAs from long-stored samples in our repository, we intend to assess miRNA expression in a large cohort of patient samples. This comprehensive evaluation will allow us to address the crucial question of miRNA utility as a prognostic and predictive biomarker.

Neoadjuvant treatment offers the chance to tailor therapy based on the tumor’s observed response during therapy and allows for adjustments, such as escalating, de-escalating or switching to other systemic regimens. Biomarkers for predicting treatment response play a crucial role in all these scenarios. Combining both liquid biopsy and imaging represents a promising approach for predicting and optimizing neoadjuvant systemic treatment in BC.55, 56

Limitations

To our knowledge, there are no prior reports of recovery of miRNA from serum samples stored for this length of time compared to the expression of freshly collected samples. Nonetheless, we have to admit several drawbacks. MiRNA in archival samples was derived from serum, whereas in freshly collected samples from plasma. In addition, we acknowledged the difficulty of drawing conclusions from comparisons between early and advanced BC patients. However, in this pilot study, we primarily wanted to assess whether it is possible to measure miRNA levels in samples from our repository, and samples derived from advanced BC patients were chosen as anticipated to have measurable levels of most miRNAs. We have to emphasize that the utility of miRNA evaluation in long-stored samples was assessed specifically in samples derived from 20 patients. The potential correlation between the expression levels of different miRNA types and treatment response, particularly early metabolic response, is an intriguing issue. However, data on early response assessment using a combination of FDG-PET-CT and miRNA in BC patients undergoing neoadjuvant systemic therapy are lacking. Currently, due to the limited number of patients in this pilot study, drawing definitive conclusions is challenging. Further evaluation would be conducted after testing a larger sample size since the vast majority of patients in our cohort underwent FDG-PET-CT scans with early metabolic assessment after the 1st chemotheraphy cycle.

For now, circulating miRNAs were not compared to tissue expression. Nevertheless, due to the positive results of our study, our next step would be to proceed with genetic testing of tumor tissue and an extensive assessment of serum samples in our repository. The timing seems optimal: on the one hand, our dataset is mature; patients were treated around a decade ago, and we have complete results concerning DFS, overall survival and long-term treatment toxicity. On the other hand, patients were diagnosed and treated according to current guidelines with modern chemotherapy regimens and the addition of trastuzumab as needed.

Conclusions

MiRNA can be identified from long-stored samples, making large prospectively collected serum repositories with long follow-up time an invaluable source for miRNA biomarker discovery. Specifically, miR-16, -17, -18a, -20a, -21, -27a, -30b, -222, -326, -19a, -29b, -29c, 128, -145, -146a, -193b, -195, -200b, -210, -221, -424, -451a, -1, -7a, -10b, 19b, -34a, -99a, -106b, -122, -125b, -155, -200a, -205, -223, and -340 were identified.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13619558. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Results of the normality test as presented in Fig. 1 (performed using the Shapiro–Wilk test).

Supplementary Table 2. Results of the normality test as presented in Fig. 2 (performed using the Shapiro–Wilk test).

Supplementary Table 3. Testing the assumption of normality for age and PET SUV variables in groups of patients with archival samples and patients with freshly collected samples.

Supplementary Table 4. Results of the Brown–Forsythe test for homogeneity of variance among different groups for miR-326, miR-20a and miR-128.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.