Abstract

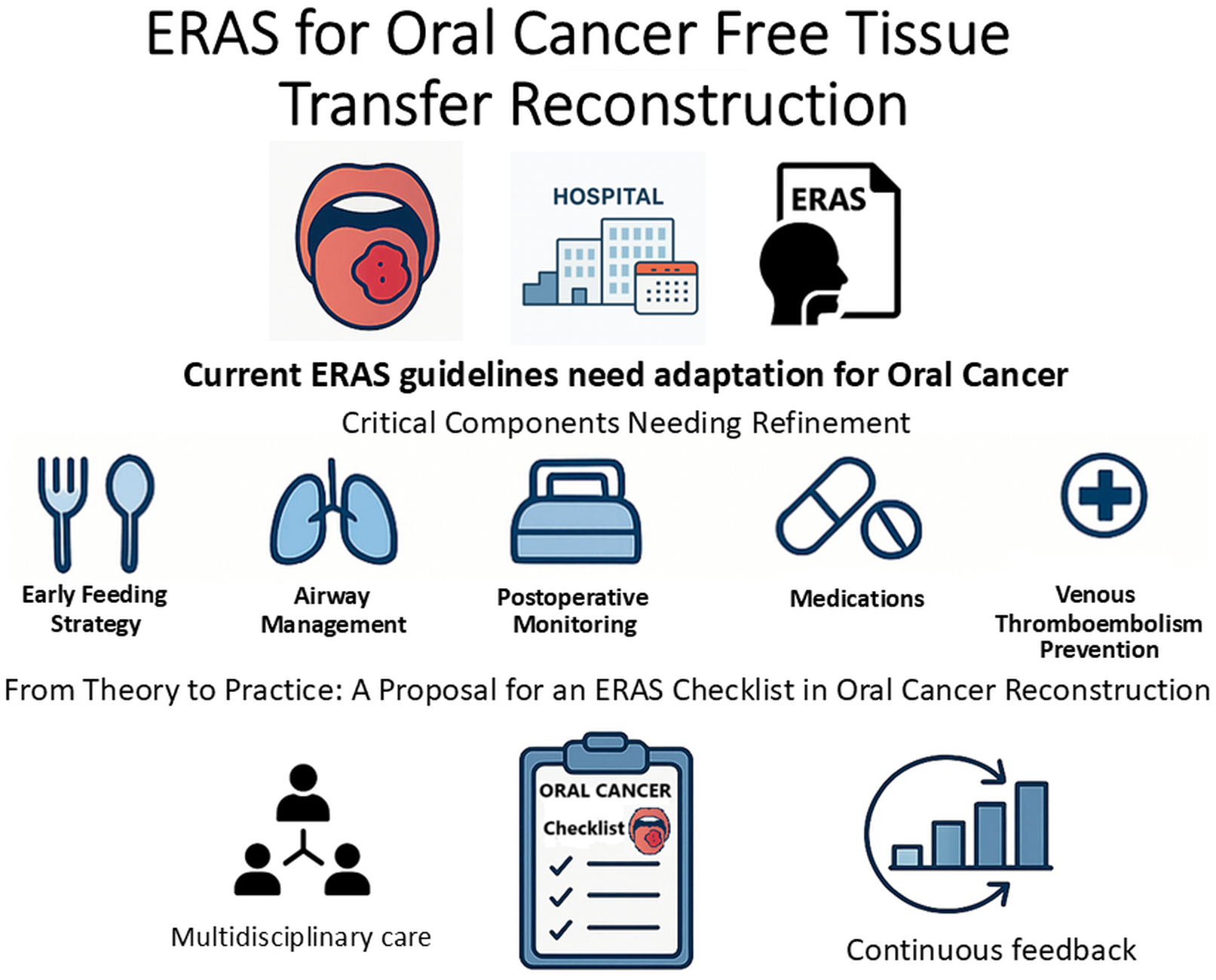

The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) consensus offers a robust framework but must be tailored to the unique challenges of free-tissue transfer reconstructions in oral cancer. Factors such as clinical heterogeneity, institutional variability, inconsistent monitoring, and the absence of internal compliance audits can undermine postoperative recovery. By fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, ERAS can evolve from a theoretical guideline into a reproducible clinical pathway that enhances survival, functional outcomes and quality of life for oral cancer patients undergoing free-tissue reconstruction. Our proposed checklist merges evidence-based recommendations with practical adaptations to establish a more consistent, auditable and outcome-driven approach to perioperative care.

Key words: oral cancer, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), perioperative care, clinical checklist

Introduction

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols have revolutionized perioperative care by substantially decreasing morbidity across numerous surgical disciplines. Dort et al. published a consensus on ERAS implementation in head and neck cancer surgery and free tissue transfer reconstruction (HNS-FTR).1 However, when extrapolating to complex oncologic oral cavity reconstructions involving FTR, the ERAS framework begins to show signs of strain. That editorial addressed major controversial issues but left universal matters uncommented upon while stating that the general principles of early mobilization, multimodal analgesia, reduced perioperative fasting, and early urinary catheter removal remain universally beneficial. Nonetheless, several core elements of ERAS in this specific surgical context require critical adaptation or, in some cases, fundamental rethinking because even seemingly straightforward opioid-sparing analgesia requires improvements in monitoring. Kemp et al.2 revealed inconsistencies in the implementation of the guidelines by showing that more than 64% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients did not receive a physician-documented pain assessment. This critical oversight highlights the urgent need for a structured checklist that includes ERAS recommendations for oral cancer FTR patients who may be tracheostomy-dependent and unable to self-report.

Preoperative nutritional optimization

The interval between diagnostic evaluation, definitive diagnosis and treatment initiation in oral cancer patients varies significantly depending on the institution and multiple individual patient factors.3 Given the significant delays before treatment reported by Rutkowska et al.,4 we believe that the time required for comprehensive diagnostics can be used to optimize the patient’s nutritional status in every case where oral cancer is suspected, using validated tools such as Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002)5 or the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST).6

Early oral feeding vs prolonged nil by mouth

Institutions vary widely in their protocols for postoperative oral intake: Some enforce a strict nil-by-mouth (NBM) regimen for 7–10 days regardless of reconstruction type, based on the traditional belief that prolonged fasting reduces the risk of flap dehiscence, compromised healing and fistula formation. Both ERAS and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) support early oral feeding, though they underscore the limitation in robust data regarding oral cancer. When oral feeding is contraindicated, enteral nutrition should be initiated within 24 h of surgery, with careful monitoring and proactive management of refeeding syndrome.1, 7, 8 Kerawala et al. showed that early oral feeding did not increase the incidence of recipient site complications and was safe, even in patients with prior radiotherapy. Moreover, it significantly reduced the length of stay (LOS), supporting a shift from routine prolonged NBM practices.9 Brady and al. supported these findings and proposed a structured early feeding protocol that commences oral intake of a liquid diet on postoperative day 1, dietitian-supported nutritional planning, swallowing assessment by a speech and language therapist (SLT), and instrumental swallowing assessments when the clinical situation is unclear.10 In our experience, rigid fasting protocols often delay recovery and undermine nutritional goals that are critical in cancer care. It is time to abandon dogma in favor of a data-driven, patient-centered approach.

Airway management: Is tracheostomy still too routine?

Free tissue transfer reconstruction (FTR) involving the tongue base, floor of the mouth and extensive mandibular resections presents particular challenges in assessing the need for elective tracheostomy. According to Ledderhof et al. and Le et al., elective tracheostomy should be reserved for patients with large lower oral cavity defects when the resection crosses the midline, involves the floor of the mouth, or requires bilateral neck dissections with FTR.11, 12 Reconstructive flaps should be designed with approx. 37% additional tissue to offset anticipated postoperative shrinkage and natural atrophy.13 In this context, postoperative edema can constrict the upper airway, posing a life-threatening risk if a tracheostomy is not performed. Although ERAS guidelines advocate for selective tracheostomy use and prompt decannulation once safe, they do not define explicit indications for elective tracheostomy, leaving this decision to the surgeon’s clinical judgment and experience. Several validated scoring systems can aid in determining the need for elective tracheostomy in head and neck surgery. Cameron’s original index evaluates factors such as surgical site, anticipated airway edema and comorbidities; Gupta’s modification refines these criteria by incorporating intraoperative findings and patient risk profiles; and the TRACHY (Tracheostomy Risk Assessment Checklist in Head and Neck Surgery) protocol, developed by Mohamedbhai, combines preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative variables to generate a composite risk score that guides both tracheostomy placement and timing of decannulation.14, 15, 16 Table 1 presents a comparison of the 3 scoring systems.

Adhikari et al. defined decannulation timing as early (≤7 days) or delayed (≥7 days),17 whereas Patel et al. recommended that, in uncomplicated cases, decannulation can be safely performed between postoperative days 3 and 6 – provided there is adequate airway patency, an effective cough and no evidence of flap compromise.18

When tracheostomy is employed, the most widely accepted and safe protocols include tracheostomy tube cuff deflation on postoperative day 1 with subsequent early decannulation and surgical closure of the tracheostomy. These procedures lead to faster recovery and more effective respiratory and swallowing rehabilitation, though individualized assessments remain critical to avoid postoperative airway emergencies.1, 19

Tracheostomy should be a carefully considered intervention rather than a routine reflex. When it is required, protocols must emphasize structured weaning and early decannulation. This approach not only safeguards the airway but also accelerates recovery, minimizes complications and restores function at the earliest clinically appropriate time.

Postoperative ICU admission: Necessary or not?

Routine postoperative admission to the ICU is a case for ongoing discussion, and we believe it is time to question the reflexive ICU admission model. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Mashrah et al., it does not improve outcomes in terms of flap survival or complication rates after HNS-FTR. Moreover, reducing ICU time or even limiting postoperative admissions can lower rates of pneumonia, sepsis, LOS, and healthcare costs.20 Based on our experience and institutional setting, it is more efficient to monitor stable patients’ when they remain in the same surgical ward rather than being transferred to the ICU, which also supports faster mobilization and improves continuity of care, but these findings require comprehensive research. Table 2 presents our institution’s decision-support criteria for ICU compared to ward admission, which is grounded in recent literature and expert consensus. The presence of a single high-risk factor may be sufficient to warrant postoperative ICU admission.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Perioperative antibiotics: Tailored duration and choice

Prolonged antibiotic use remains common in oral cavity oncology and is usually connected to bone reconstruction, segmental mandibulectomy, preoperative radiation therapy, tracheotomy, longer operative time, and LOS.13 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 min before incision and discontinuation within 24 h postoperatively. Current guidelines emphasize pathogen-directed, short-term antibiotic regimens to optimize outcomes and reduce hospital-acquired infections.1, 25, 26 In contrast, a retrospective study by Daly et al. demonstrated that shortening the duration of antibiotic prophylaxis from a median of 9 days to 1 day, including the recommended cefazolin + metronidazole regimen, led to a significant increase in surgical site infection (SSI).27

Recent evidence indicates that extending prophylactic antibiotic courses beyond 48–72 h offers no additional benefit; penicillins and cephalosporins remain the most effective agents for preventing surgical-site infections in head and neck/oral cancer surgery, whereas clindamycin performs poorly, especially in penicillin-allergic patients.26, 28, 29, 30 Iocca et al. also highlighted that most reported penicillin allergies are not confirmed upon formal testing, suggesting that many patients may be unnecessarily excluded from receiving first-line prophylaxis.26 Multidisciplinary research shows that the risk of cross-reactivity between penicillin and cefazolin is very low and supports its use in most surgical patients with a history of penicillin allergy, but current official clinical guidelines still do not fully align with these trends.31, 32 Data on the optimal duration of postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis are limited – articularly in patients undergoing vascularized bone graft reconstruction or those who have received neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, no clear consensus has been established, underscoring the need for further research, ideally randomized controlled trials focused on these high-risk subgroups. Current perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations are summarized in Table 3.

Steroid use: Limited to single preoperative dose

Corticosteroid use in ERAS protocols for head and neck surgery (HNS) remains a subject of debate. Dort et al.1 recommend a single preoperative dose of corticosteroids, primarily to reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) after some types of surgery. However, the role of extended steroid administration is more controversial. In a randomized controlled trial, Kainulainen et al. examined the effects of a total of 60 mg dexamethasone intravenously (i.v.) for 3 days. The regimen did not reduce flap edema or shorten LOS and was associated with a higher rate of postoperative infections than placebo.33

The ongoing PreSte-HN study34 is the first multicenter, placebo-controlled, phase III trial specifically addressing whether a single, low-dose preoperative dexamethasone infusion can enhance recovery without increasing complications and establishing clearly defined ERAS guidelines for HNS-FTR. Once consensus is reached, the checklist should include a single preoperative dose of steroids; routine use of steroids beyond that single dose is not supported by the literature and may be harmful.

Venous thromboembolism prevention: Multimodal, risk-based strategy

Thromboprophylaxis following oral cancer FTR, where the balance between thrombosis and bleeding is particularly delicate, has led to wide variations in clinical practice; some centers initiate low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) within 6–12 h following the operation, while others delay pharmacologic prophylaxis, relying initially on mechanical methods.

Low-molecular-weight heparin and unfractionated heparin (UFH) are effective options for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, with LMWH offering practical advantages such as predictable dosing and longer half-life, though no clear superiority has been proven. Aspirin alone is not recommended for VTE prophylaxis, and its role remains unclear since evidence indicates increased bleeding when combined with other anticoagulants.35

Current expert consensus supports a multimodal approach combining pharmacologic agents with mechanical prophylaxis, like intermittent pneumatic compression and early mobilization. Low-molecular-weight heparin should ideally commence within 12 h of surgery (following hemostasis) at prophylactic doses (40 mg daily) and continue for at least 7 days or extend to 28 days in high-risk scenarios (previous VTE, obesity, prolonged immobilization, and advanced cancer stage). It is also vital to assess patients’ individualized thromboembolism risk factors preoperatively and adjust prophylaxis accordingly.

At present, the routine continuation of anticoagulant therapy to prevent metastatic spread is not standard practice, although preclinical studies indicate that anticoagulants may possess antitumor properties.36

Conclusions

Perhaps the most glaring weakness in ERAS implementation for oral cavity reconstruction is the lack of monitoring systems. Protocols are frequently adopted in theory but inconsistently applied. Furthermore, elements such as early feeding, pain control, ambulation, and tracheostomy weaning are often left without documentation or audit.

Given the increasing volume of microvascular procedures, there is a clear need for targeted research and consensus-building. ERAS should function as a living, actively implemented protocol – not a checklist gathering dust in a drawer. It should be a dynamic system, not a static guideline, that evolves with evidence, audits its own effectiveness, and adapts to institutional realities. Our proposed checklist (Table 4), a first step toward that vision, is a user-friendly protocol that centers not on what is easy but on what is necessary, a literature-based approach to optimal recovery.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.