Abstract

Background. The spread of antibiotic-resistance genes among healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) poses serious problems in the treatment of these infections. Recently, these resistance genes have also been shown to be present in integrons.

Objectives. By focusing on integron-mediated mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, we sought to elucidate the genetic determinants underpinning the development of multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii.

Materials and methods. In this study, 27 TMP-SXT-resistant A. baumannii isolates were obtained from various clinical samples. Class I and class II integrons were determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Samples were sent for DNA sequence analysis of the integron to a private firm (BMLabosis, Ankara, Turkey). The similarities of the DNA sequences with the associated integron were determined using National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank.

Results. While all isolates were resistant to TMT-SXT and gentamicin, amikacin and tobramycin resistance rates were detected as 70% and 26%, respectively. Class I and class II integrons were found in 1 strain and 2 isolates, respectively. It was also determined that the dfrA12 gene and the aadA2 gene were found in the class I integrons. It was determined that 2 isolates carrying class II integron had dfrA1 and sat2 genes. Both class I and class II integrons were detected in 1 of these isolates.

Conclusions. Despite the low integron detection in the resistant isolates, with the detection of class I and class II integrons among A. baumannii isolates, it was determined that HAIs could spread very rapidly within the hospital and cause multidrug resistance. This study reveals the need for comprehensive surveillance and molecular characterization of integron-mediated resistance mechanisms to inform effective strategies to combat infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii.

Key words: antibiotic resistance, Acinetobacter baumannii, integron gene cassettes

Background

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), commonly known as nosocomial infections, represent a significant burden on global public health, particularly due to the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial species as their primary causative agents. These infections have garnered attention as the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, a designation emphasized by authoritative bodies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).1 The pervasive presence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in healthcare settings poses formidable challenges for clinicians, infection control practitioners and policymakers alike. With conventional treatment options increasingly compromised by the relentless evolution of resistance mechanisms, addressing the complex dynamics of HAIs and antibiotic resistance emerges as an urgent priority in safeguarding patient safety and optimizing healthcare outcomes.2, 3 Healthcare-associated infections, also known as nosocomial infections, pose substantial medical and economic burdens not only in Turkey but globally.3, 4 Furthermore, it was observed that bacterial co-infections were very common in people with an underlying viral infection; specifically during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, a global health threat commonly spread through respiratory droplets and aerosol transmission. Pneumonia and bloodstream infections (BSIs) were the most common causes of bacterial HAIs in COVID-19 patients.5 These infections contributed to prolonged hospital stays and led to severe complications in a significant proportion of hospitalized patients, ranging from 5% to 15%.3, 4 Given the limited availability of effective antibiotic therapies for treating these infections, understanding the antibiotic resistance profiles and underlying resistance mechanisms of causative pathogens is crucial. Such knowledge is essential for informed antibiotic selection and plays a pivotal role in efforts aimed at reducing the rates of antibiotic resistance.3

In recent years, the incidence of infections caused by microorganism species, also known as ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter sp.), has not only increased but also due to multiple antibiotic resistance, these infections have increased. There are serious difficulties in the prevention, treatment and eradication.6 In 2018, A. baumannii was at the top of the list of “resistant bacteria that urgently require new antibiotic discovery” due to increasing resistance rates, published by the WHO.7 Acinetobacter baumannii is normally found in the soil and is a microorganism that can cause high levels of arsenic accumulation in the soil.8 However, this bacteria can cause, especially in intensive care units (ICUs), many different infections and severe clinical conditions such as ventilator-associated pneumonia and catheter-associated bacteremia, urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections, septicemia, and meningitis, and it also causes failures in the control and treatment of infections, as well as a significant increase in healthcare costs.9 The antibiotic resistance profile in A. baumannii isolates may vary regionally and yearly, increasing antibiotic resistance and the occurrence of multiple antibiotic resistance infections cause clinicians to note serious difficulties in the management and treatment of patients.10, 11 In recent years, Turkey and other countries have experienced a significant increase in the incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii isolates. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter strains are generally MDR, and colistin or tigecycline are often used as a last resort in the treatment of A. baumannii. However, strains that are resistant even to these antibiotics have been reported.12

Carbapenems, aminoglycosides, sulbactam, colistin, and tigecycline are antimicrobial agents frequently used in the treatment of Acinetobacter infections that cause serious clinical conditions. While different groups of antibiotics can be used in the treatment of A. baumannii infections, treatment strategies aimed at eradicating the infection are mostly focused on broad-spectrum antibiotics.9 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SXT) is recommended as the first choice, especially in the treatment of HAIs, due to its high potency against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; it can be used on a wide patient profile. However, in recent years, studies conducted in different geographical regions have begun to report the development of resistance against TMP-SXT.10, 13 Previously, MDR A. baumannii infections could be treated with this antibiotic combination in sporadic cases, but now it is observed that resistance to this drug has become widespread in over 80% of isolates.14 Plasmids and integrons-induced changes in the dihydropteroate synthetase enzyme cause sulphonamide resistance in A. baumannii.15 If this resistance can be prevented or slowed down, effective treatment of healthcare-associated A. baumannii isolates can be achieved without the switch to last-resort antibiotics. Some researchers report that, due to resistance of A. baumannii to many antibiotics, studies aimed at elucidating its antibiotic resistance mechanisms should be continued in order to prevent becoming helpless in the face of infections.9, 16

In research concerning the acquired antibiotic resistance mechanisms of bacteria, a multitude of mobile genetic elements have been uncovered, including transposons, plasmids and integrons.17 Comparative sequence analyses of these elements have unveiled the presence of integrons, which represent a pivotal discovery in understanding the genetic basis of antibiotic resistance.18, 19 Integrons are characterized as DNA elements harboring mobile gene cassettes along with a site-specific recombination system. These gene cassettes can encode various antibiotic resistance determinants, facilitating their dissemination among bacterial populations through horizontal gene transfer mechanisms.20 Integrons play a crucial role in the evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance genes, enabling bacteria to rapidly acquire and accumulate resistance traits, thereby posing significant challenges to clinical treatment strategies and public health efforts.21

Objectives

This investigation aimed to comprehensively examine the prevalence and distribution of class I and class II integron gene cassettes within TMP-SXT-resistant strains of A. baumannii. Also, by focusing on integron-mediated mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, particularly concerning TMP-SXT resistance, this research sought to elucidate the genetic determinants underpinning the development of multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of A. baumannii.

Materials and methods

A. baumannii isolates

This research was conducted in line with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee for Scientific Research in Health Sciences at Kırşehir Ahi Evran University (Kırşehir, Turkey) approved the study (approval No. 2024-04.17 issued on February 6, 2024). Twenty-seven Acinetobacter baumannii isolates resistant to TMP-SXT were obtained from various clinical samples used for routine diagnosis at the Kırsehir Training and Research Hospital in Turkey between September 2021 and November 2022. Identification and antibiotic susceptibilities of the isolates were performed using the Vitek-2 Automated System (BioMérieux SA, Craponne, France) at the the Kırsehir Training and Research Hospital. The phenotypic and demographic characteristics of A. baumannii isolates are provided in Table 1, Table 2.

DNA extraction

Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the Kırşehir Training and Research Hospital Medical Microbiology Laboratory Culture Collectionwere brought to the Medical Microbiology Laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine of Kırsehir Ahi Evran University via cold chain. Bacterial isolates were cultivated on blood agar under aseptic conditions and incubated at 37°C. DNA extraction from A. baumannii isolates was performed using the boiling method. A loopful from pure cultures was taken, dissolved in 300 µL of pure water, and incubated at 100°C for 10 min. Then, the samples were kept at room temperature and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used as template DNA.22

Detection of class I and class II integron gene cassettes

In this study, the presence of class I and class II gene cassettes in A. baumannii isolates was determined with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Specific primers used to amplify integron gene cassettes are shown in Table 3. Primers specific to integron gene cassettes were used in the PCR reaction. The PCR reaction was prepared by adding 1X PCR buffer without MgCl2 (10 mM tris-HCl, pH 8.3 at 25°C, 50 mM KCl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM dNTP mix, 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, and 10 pmol/µL of each primer in a final volume of 50 µL. The final volume of the reaction was completed with sterile dH2O.23

Polymerase chain reaction conditions for the amplification of integron gene cassettes were as follows; first, the denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min, then 36 cycles of 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 50°C, 5 min at 72°C, and a final extension was applied for 10 min at 72°C. Imaging of PCR products was done on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis containing ethidium bromide (EtBr) at 100 V for 1 h and observed under UV light. The size of the integron gene cassettes was determined by comparison with the DNA ladder. Samples were sent to BMLabosis (Ankara, Turkey) for DNA sequence analysis of integron gene cassettes.23

Bioinformatics

All DNA sequences obtained from integron gene cassettes were processed using the BioEdit 7.09 program (Tom Hall, Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, USA) Similarities of the DNA sequences with their associated integron gene cassettes were determined using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank Blast database.24, 25 The obtained data were used to determine integron gene cassettes.

Genbank acceptance numbers

In this study, the GenBank acceptance numbers of the class I and class II integron sequences for the A. baumannii CO1 isolate were deposited in GenBank as OR417416 and OR417417, respectively. The GenBank accession number of the class II integron sequence for the A. baumannii CO2 isolate was deposited in GenBank as OR417418.

Results

In our comprehensive study, we investigated the antimicrobial resistance profiles of 27 Acinetobacter baumannii isolates, focusing on their susceptibility to a range of antibiotics commonly used in clinical practice. It was observed that all A. baumannii isolates exhibited resistance to TMP-SXT and gentamicin antibiotics, indicative of a concerning trend in multidrug resistance. Furthermore, a significant proportion of isolates demonstrated resistance to amikacin and tobramycin, with rates of 70% and 26%, respectively. Notably, none of the isolates exhibited resistance to colistin and tigecycline antibiotics, suggesting their continued efficacy as last-resort treatment options against A. baumannii infections (Table 1).

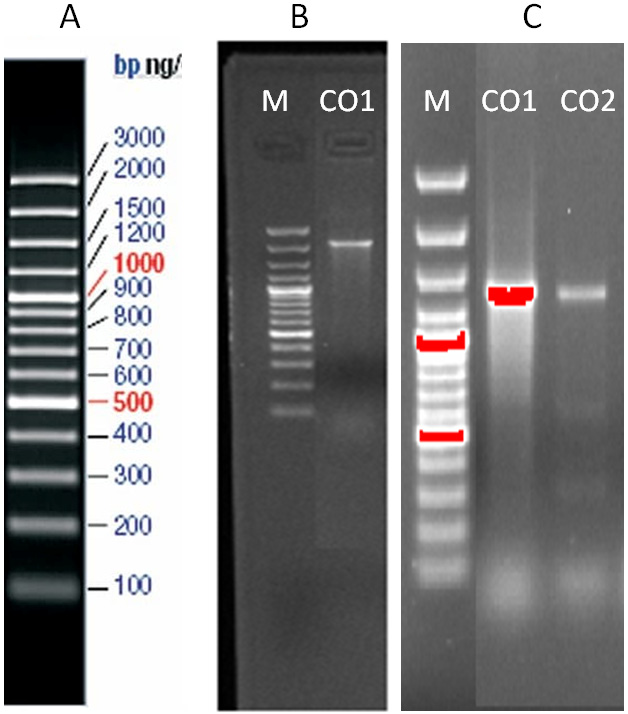

In addition to evaluating antimicrobial susceptibility, our study delved into the molecular mechanisms underlying antibiotic resistance, specifically focusing on the presence of integron gene cassettes. Through agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequent DNA sequencing, we detected the presence of class I and class II integrons in select TMP-SXT-resistant A. baumannii isolates. Specifically, 1 isolate (CO1) harbored a class I integron gene cassette, while both class I and class II integron gene cassettes were identified in 2 isolates (CO1 and CO2). The molecular characterization revealed that the class I integron gene cassette was approx. 2,000 base pairs in size, while the class II integron gene cassette measured approx. 1,271 base pairs (Figure 1).

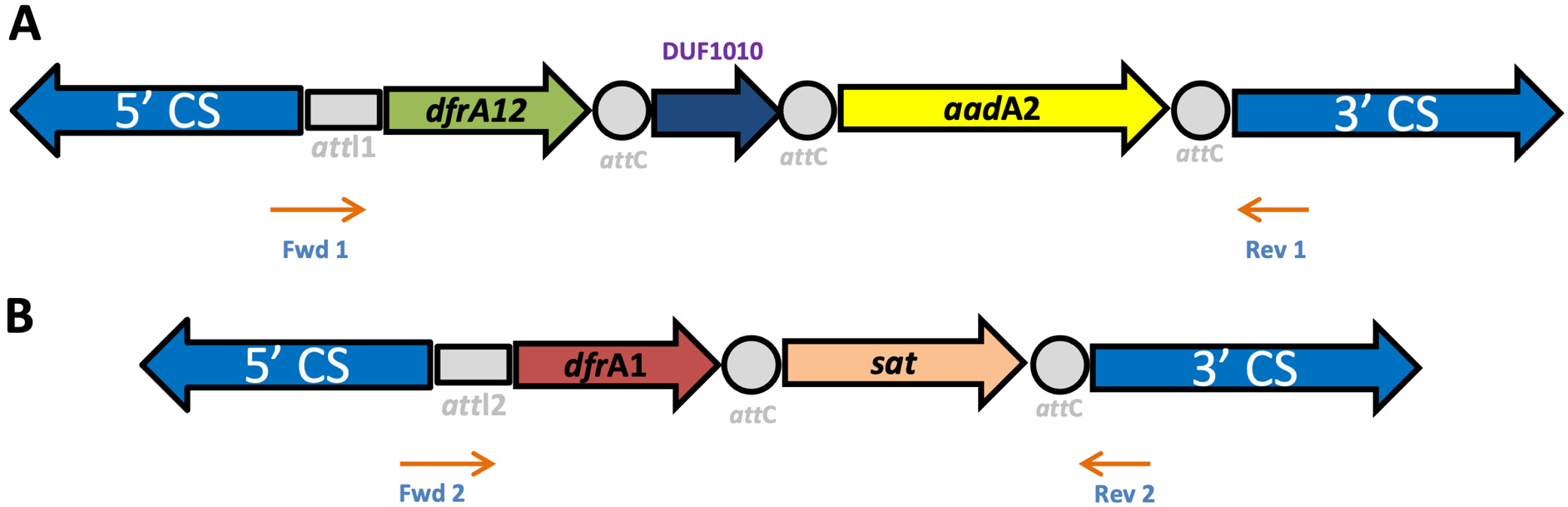

Further bioinformatic analysis, conducted through NCBI GenBank Blast, elucidated the genetic composition of the integron gene cassettes. Specifically, we identified the presence of the dfrA12 gene, encoding the dihydrofolate reductase enzyme associated with TMP-SXT resistance, and the aadA2 gene, encoding the aminoglycoside 3’-O-nucleotide transferase enzyme responsible for aminoglycoside resistance, within class I integrons (Table 4). Notably, our study also unveiled the co-occurrence of both class I and class II integron gene cassettes within a single isolate, underscoring the complexity of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in A. baumannii populations (Figure 2).

Discussion

Due to the increasing multidrug resistance strains of A. baumannii in recent years, it has become more difficult to treat and control HAIs, and it is associated with increases in mortality.26 Antibiotic resistance generally occurs horizontally through mobile elements such as transposons and plasmids. Integrons play an important role in the spread of antibiotic resistance among species due to their ability to integrate and carry extrachromosomal genetic elements such as plasmids or transposons. The emergence of integron gene cassettes in MDR A. baumannii isolates has led to the restriction of treatment alternatives against the agent and increased interest in searching for alternative treatments against the agent.27

The escalating multidrug resistance observed in A. baumannii infections poses significant challenges in clinical management and infection control, causing increased mortality, morbidity and healthcare costs for hospitals.18 Horizontal transmission of antibiotic resistance genes, facilitated by mobile genetic elements such as transposons and plasmids, exacerbate this threat. Among these transmission mechanisms, integrons have emerged to play a pivotal role in mediating the dissemination of antibiotic resistance, owing to their capacity to capture and incorporate extrachromosomal genetic material, including plasmids and transposons. The emergence of integron gene cassettes within MDR A. baumannii strains has severely limited therapeutic options and underscored the urgent need for alternative treatment modalities.27

In studies on the antibiotic resistance of A. baumannii isolates, the resistance status of TMP-SXT-resistant isolates to different antibiotics varies according to years and regions.10, 26, 27, 28 In accordance with previous research findings, our study revealed that A. baumannii isolates exhibited resistance to TMP-SXT, as well as varying degrees of resistance to gentamicin (100%), amikacin (70%) and tobramycin (26%), while all isolates remained susceptible to colistin and tigecycline.

Integrons, especially in Gram-negative bacteria, possess the capability to transfer horizontally between bacteria via plasmids and transposons, facilitating both the dissemination of integrons between bacterial strains and the exchange of integron gene cassettes. This phenomenon contributes to intraclass variability in antibiotic resistance determinants within integrons and enables the rapid transmission of diverse antibiotic resistance traits among bacterial populations.29 Our study data corroborate the presence of class I and class II integron gene cassettes encoding distinct antibiotic resistance determinants among A. baumannii isolates. By elucidating the genetic mechanisms underpinning antibiotic resistance, our findings underscore the importance of integrative approaches in combating MDR bacterial infections. Kostakoğlu et al.25 reported that a class I integron gene cassette containing the dfr gene was detected in 45.4% of A. baumannii isolates resistant to TMP-SXT, while 6.4% of isolates sensitive to TMP-SXT also harbored this cassette. Similarly, in another study, it was found that 9.1% of A. baumannii isolates carried 2 different class I integron gene cassettes encoding aacC1-aadA1 and aac(3)-I genes.25 In contrast, Xu et al.29 reported the presence of class I integrons in 13.51% of A. baumannii isolates but could not detect class I or class II integron gene cassettes. A multicenter study conducted across various regions in Turkey revealed that class I integrons were found in 6.4% of A. baumannii isolates, whereas class II integron gene cassettes were not detected. The class I integron identified in this study contained resistance genes such as aac(3)-1, aadA1 and blaTEM-1.30 Conversely, in a study conducted in Iran, the rates of class I and class II integron gene cassettes in A. baumannii isolates were detected in 63.9% and 78.2%, respectively. Intriguingly, both class I and class II integron gene cassettes were identified in 49.6% of the isolates, although the specific antibiotic resistance genes within these cassettes were not elucidated.27

In this research conducted in the Kırşehir province in Turkey, both class I and class II integrons were detected in A. baumannii isolates. In our study, contrary to previous findings, the simultaneous presence of dfrA12 and aadA genes within class I integron gene cassettes indicates the existence of multiple subtypes of genes responsible for TMP-SXT and aminoglycoside resistance. This observation suggests a potential mechanism for the amplification of class I integrons contributing to multidrug resistance among A. baumannii isolates. Additionally, unlike previous studies, our research identified the co-occurrence of both class I and class II integrons within the same bacterial isolate. The presence of dfrA12 and aadA2 genes (GenBank accession No. OR417416) within the class I integron, along with dfrA1-Sat genes (GenBank accession No. OR417417) within the class II integron, underscores the likelihood of multiple integron gene cassettes harboring distinct genes in A. baumannii strains. This situation suggests the potential for rapid dissemination of multiple antibiotic resistance traits among the isolates. In addition to the aforementioned findings, another noteworthy observation was the presence of the sat gene alongside the dfrA1 gene in an A. baumannii isolate carrying a class II integron. This observation implies that the dissemination of aminoglycoside resistance among TMP-SXT-resistant A. baumannii isolates might exhibit a heightened prevalence compared to other antibiotic resistance genes.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study was the sample size. It is essential to conduct integron gene cassette studies that examine antibiotic resistance on a population level, encompassing a diverse range of bacteria with varying resistance profiles. Such studies necessitate a coordinated national approach, and these limitations will be the primary focus of future research.

Conclusions

As a result of the analysis of the data we obtained in our research, it was revealed that colistin and tigecycline are still the most effective antibiotics in the treatment of infections caused by A. baumannii. Furthermore, this study reveals the need for comprehensive surveillance and molecular characterization of integron-mediated resistance mechanisms to inform effective strategies to combat infections caused by MDR A. baumannii.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.