Abstract

Background. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is characterized by rapid onset, rapid development and a high short-term mortality rate. Systemic inflammation exerts an effect on the disease progression of ACLF.

Objectives. The purposes of this study were to explore the clinical significance that the inflammatory response has on the disease process of hepatitis B virus acute-on-chronic liver failure (HBV-ACLF) patients, to further compare the values of different inflammation-related biomarkers in the prognosis evaluation of HBV-ACLF patients, and to combine inflammatory-related markers to establish a new prediction model.

Materials and methods. Baseline admission data and 90-day outcomes were collected from 247 patients who met the inclusion criteria. According to the 90-day survival situation, they were divided into a survival group and a death group. The differences in baseline data and inflammation levels between the 2 groups were compared. A regression model was used to analyze the risk factors for 90-day mortality and establish a new model.

Results. The study found that the differences between the survival group and the death group were statistically significant in terms of age, total bilirubin (Tbil), prothrombin time (PT), international standardized ratio (INR), inflammation level, and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) series scores (p < 0.05). The monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR)-integrated iMELD model (MLR-iMELD) can effectively predict the 90-day survival rate of HBV-ACLF patients. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) of the new model was 0.792, and the best cutoff for predicting the prognosis of 90 days for patients was –0.33 (sensitivity 0.577 and specificity 0.898).

Conclusions. The higher the level of inflammation in patients with HBV-ACLF, the greater the risk of 90-day death. Compared with other inflammation-related markers, the MLR-iMELD model can better predict the 90-day survival rate of HBV-ACLF patients.

Key words: inflammation, prognosis, hepatitis B virus, HBV-ACLF

Background

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) has gained increasing recognition due to its high short-term mortality rate.1 The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) defines ACLF as an acute liver injury that occurs as a result of chronic liver disease and is triggered by acute factors. Among them, acute liver damage induced by hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation, alcohol consumption and infection are the most common. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is characterized by jaundice and coagulation dysfunction, and it is prone to clinical ascites and/or hepatic encephalopathy.2 Although there is still no consensus for the definition of ACLF, the poor clinical prognosis in patients with ACLF is undeniable. With changes in the epidemiological profile of ACLF in the Asia–Pacific region, the proportion of acute liver injury caused by alcohol has increased gradually, but acute liver injury caused by HBV reactivation is still the main reason.3 The progression from compensated to decompensated and ACLF after HBV infection is characterized by complications related to cirrhosis and extrahepatic organ tissue damage.4

The strong inflammatory reaction caused by immune activation or inhibition during the progression of ACLF is crucial for the prognosis of patients.5 Indeed, some studies have confirmed that certain inflammation-related blood laboratory indicators, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), platelet-to-leukocyte ratio (PWR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), among others, can better reflect the baseline inflammatory response and immune status of patients with ACLF or non-ACLF patients.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In addition, some inflammatory combination indicators, such as the systemic immune–inflammation index (SII) and the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), have certain clinical value in non-ACLF diseases, but the above indicators are rarely reported in HBV-ACLF.11, 12, 13 Given the high short-term mortality of HBV-ACLF, early identification and evaluation of the severity of the disease are critical for subsequent treatment and improved patient outcomes. Various prognostic models, including the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), COSSH-ACLF score and CLIF-C ACLF score, are considered suitable for predicting the prognosis of patients with HBV-ACLF.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Among the above models, the MELD serial scoring model (MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD) does not consider the influence of infection and inflammation. Although neutrophils are included in the COSSH-ACLF score, there is a certain subjective bias due to the inclusion of the hepatic encephalopathy score in the model. For the CLIF-C score, which includes white blood cell count (WBC), its clinical application also has certain limitations because white blood cells are easily affected by hypersplenism.

Objectives

Therefore, this study will further explore the influence of the inflammatory response on HBV-ACLF and compare the clinical value of single inflammation-related indicators for prognostic evaluation. It will suggest a new model with better evaluation efficiency combined with inflammation-related indicators.

Materials and methods

Patients

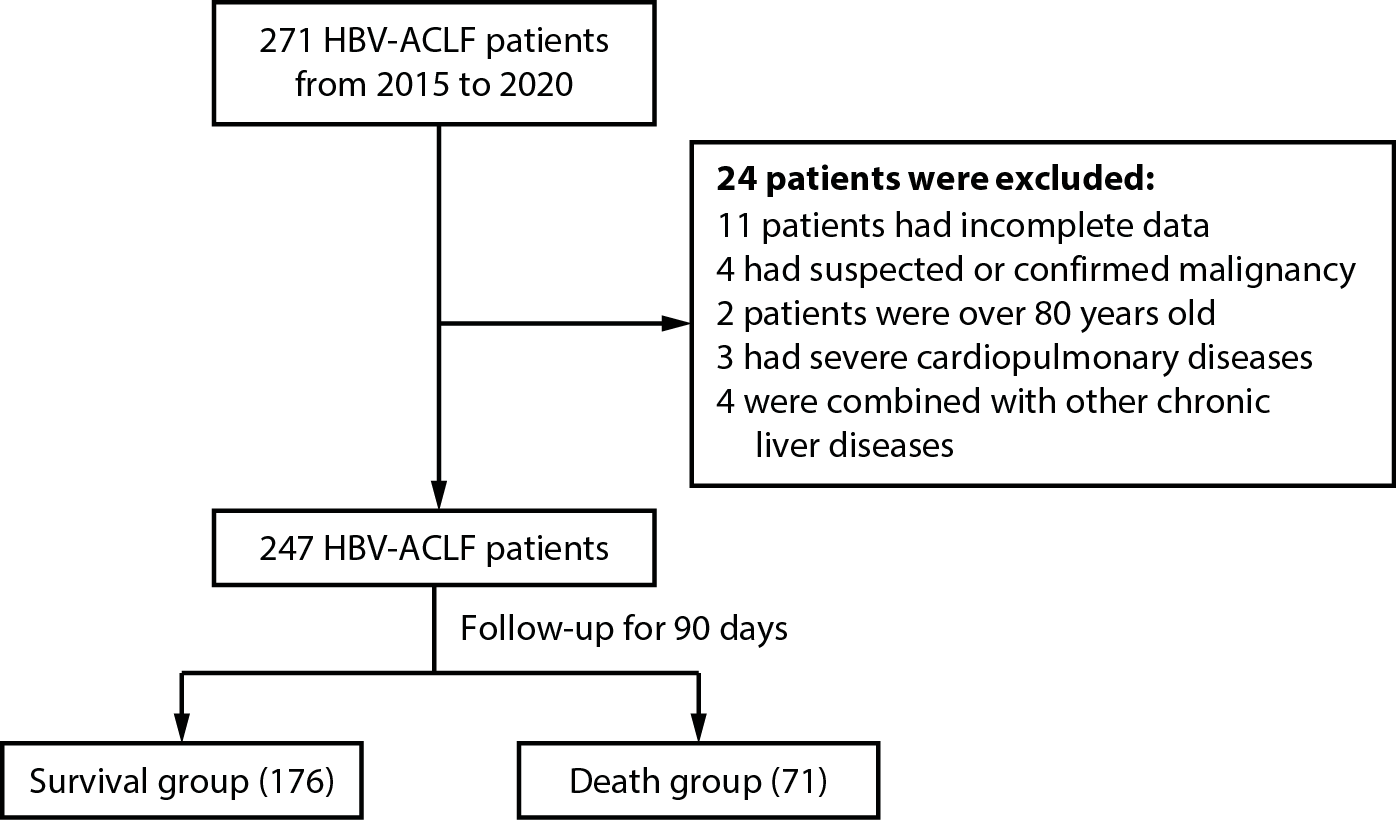

This is a retrospective observational study. In view of the high incidence of HBV in the Asia–Pacific region, we enrolled patients with HBV-ACLF who met the definition of the APASL: “ACLF is an acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥5 mg/dL or 85 micromol/L) and coagulopathy (international standardized ratio (INR) ≥ 1.5 or prothrombin activity <40%) complicated within 4 weeks by clinical ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease/cirrhosis and is associated with a high 28-day mortality”.2 We collected the records of HBV-ACLF patients from 2015 to 2020 at the People’s Liberation Army The General Hospital of Western Theater Command (Chengdu, China). The study included a total of 271 patients; 24 patients were excluded according to the exclusion criteria, leaving 247 patients who were ultimately included in the study group. All patients were followed up for 90 days, mainly through the hospital medical record system and telephone communication. The study endpoint was the patient’s survival at 90 days, and the secondary endpoint was death or liver transplantation. The exclusion criteria were: 1) patients under 18 and over 80 years of age; 2) viral infections other than HBV; 3) combined with other types of chronic liver disease; 4) patients with severe cardiopulmonary disease or chronic kidney disease (CKD); 5) suspected or confirmed malignancy; 6) pregnant or breastfeeding; 7) received a liver transplant; 8) no recent history of hormone or antibiotic use; and 9) incomplete data (Figure 1).

Clinical data collection

Baseline data and 90-day survival were collected. All clinical data were collected through the hospital health system, and 90-day survival was followed up by telephone by the investigators. Clinical data mainly included routine blood tests (platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and leukocytes) and blood biochemical indexes (albumin, prealbumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (Tbil), and coagulation parameters (prothrombin time (PT) and INR)). Upon admission, patients underwent calculation of their MELD serial scores. Baseline inflammation-related measures were calculated as follows: NLR = neutrophil (×109/L)/lymphocyte (×109/L), MLR = monocyte (×109/L)/lymphocyte (×109/L), SII = platelet (×109/L) * NLR, PLR = platelet (×109/L)/lymphocyte (×109/L), PWR = platelet (×109/L)/leukocyte (×109/L), and PNI = albumin (g/L) + 5 * lymphocyte (×109/L).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SPSS v. 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of quantitative data. Continuous variables conforming to the normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (±SD); if not normally distributed, they were expressed as median (Q1–Q3). Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to test the correlation between MELD score and other clinical characteristics of patients. Non-parametric tests were used to determine the indicators with statistical differences between the 2 groups. Multivariate regression models were used to determine the risk factors for 90-day mortality based on the results of multivariate logistic regression to construct a new prediction model. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to further analyze the performance of the model, and the cumulative survival rate of the HBV-ACLF patients at 90 days was plotted using a Kaplan–Meier curve. For all statistical analyses, p-values were two-sided, and p ≤ 0.1 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 247 HBV-ACLF patients were included in this study. The characteristics of the patients and their laboratory data are shown in Table 1. Among the 247 participants, 176 were in the survival group and 71 were in the death group, with a 90-day survival rate of 71.26%. By comparing the 2 groups, it was found that the levels of platelets, lymphocytes, albumin, ALT, and PWR were significantly higher in the survival group than in the non-survival patients. The age of the patients in the survival group and their PT, INR, AST, serum creatinine, TBil, neutrophils, monocytes, NLR, MLR, MELD, MELD-na, and iMELD score were significantly lower than those in the death group (p < 0.05).

Correlation between inflammatory biomarkers and MELD score

To further understand the correlation between inflammation and the disease status of patients, we used Pearson’s correlation analysis to confirm our conjecture. The results showed that there was a certain correlation between inflammation-related markers and MELD score in HBV-ACLF patients, among which NLR, MLR, SII, PNI, leukocyte count, neutrophil count, and monocyte count were positively correlated with MELD score (r-values of 0.254, 0.496, 0.133, 0.145, 0.319, 0.214, and 0.423, respectively). Conversely, PWR and lymphocyte count were negatively correlated with MELD score (r-values of –0.425 and –0.188, respectively) (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Comparing the predictive value of inflammatory biomarkers and establishing a new predictive model

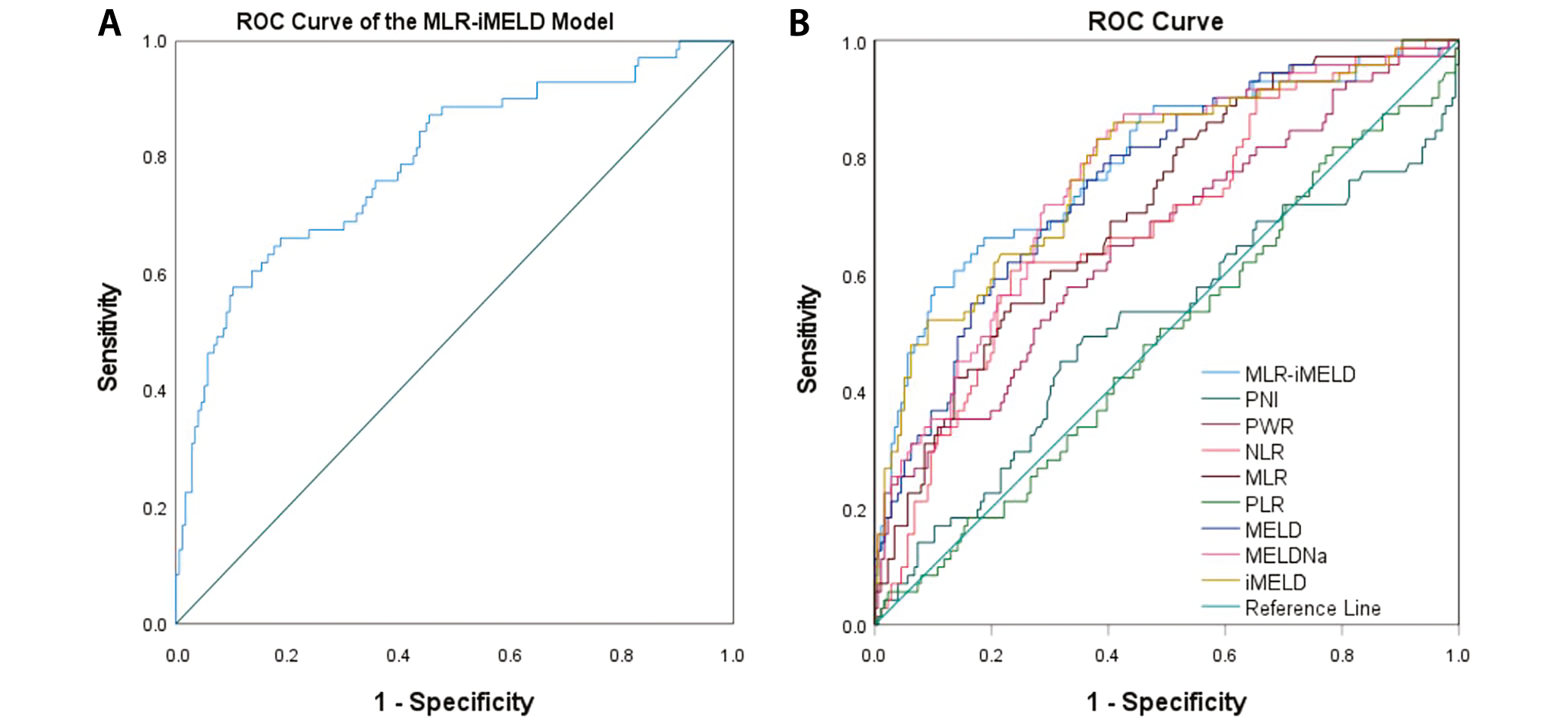

We compared 90-day survival rates in the 247 hepatitis B virus acute-on-chronic liver failure (HBV-ACLF) patients, among which there were 176 (71.26%) survivors and 71 (28.74%) deceased. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used to screen the variables (Table 3). We found that MLR and iMELD were independent predictors of patient outcomes at 90 days (p < 0.1). Therefore, we developed a new prognostic model (MLR-iMELD score) for patients with HBV-ACLF. The mathematical formula was as follows: MLR-iMELD score = 0.855 × MLR + 0.125 × iMELD – 6.768. To further evaluate the predictive value of the new model, we compared the clinical values of NLR, MLR, PWR, PLR, PNI, MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD, and MLR-iMELD scores by analyzing the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) (Figure 2). Except for PLR and PNI, all other indicators showed statistical significance. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.606 and 0.767 for NLR, 0.549 and 0.767 for MLR, 0.577 and 0.670 for PWR, 0.803 and 0.597 for MELD score, 0.831 and 0.619 for MELD-Na score, 0.831 and 0.619 for iMELD score, and 0.577 and 0.898 for MLR-iMELD score, respectively (Table 4). The AUROC curves were 0.684 (0.611–0.758) for NLR, 0.711 (0.641–0.780) for MLR, 0.656 (0.579–0.733) for PWR, 0.510 (0.424–0.596) for PNI, 0.758 (0.692–0.825) for MELD score, 0.761 (0.695–0.827) for MELD-Na score, 0.781 (0.715–0.847) for iMELD score, and 0.792 (0.727–0.857) for MLR-iMELD score (Table 4).

Performance of the MLR-iMELD model

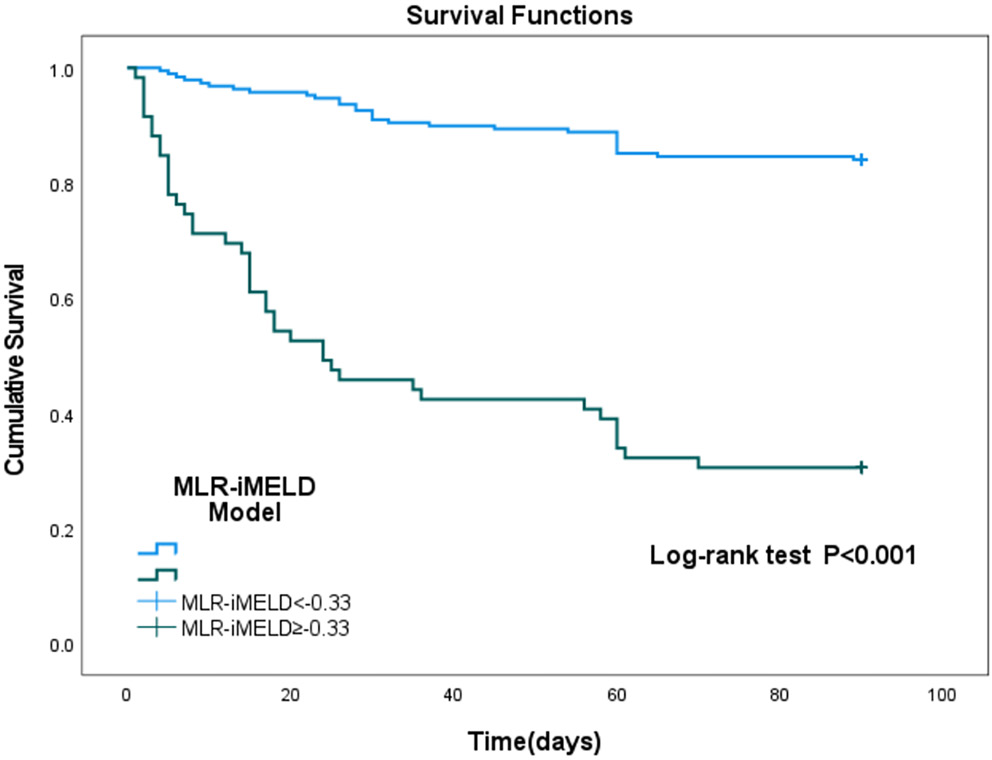

By comparing the new model with other inflammation ratios and models, we found that the new model had better clinical value than the MELD series score and the single inflammation index. Based on the AUROC results, the best cutoff value (Youden’s index) for identifying MLR-iMELD was –0.33 (sensitivity: 0.577; specificity: 0.898). Patients were divided into 2 groups (MLR-iMELD ≥ –0.33 and MLR-iMELD < –0.33) according to the preselected cutoff points. In order to verify the effectiveness of the model, we further compared the 90-day survival rates of the 2 groups of patients. The Kaplan–Meier curves found that patients with MLR-iMELD scores higher than the cutoff value of –0.33 had a greater risk of poor prognosis (Figure 3).

Discussion

It is well known that ACLF is a clinical syndrome with acute onset, rapid progression and poor prognosis. The prognosis and treatment of ACLF according to various causes of chronic liver disease are different. Due to the high rate of HBV infection in the Asia–Pacific region, there is also a high incidence of HBV-ACLF in this region.19 With the proposed systemic inflammation hypothesis, systemic inflammation is considered to be related to the disease progression and prognosis of ACLF. Systemic inflammation caused by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) induced by certain events (such as infection, viral reactivation, alcohol consumption, etc.) is an important factor, and it can act indirectly through changes in circulatory function and metabolism, as well as directly induce tissue damage.20 In patients with chronic HBV infection, acute exacerbation or recurrence of HBV is the main factor causing acute liver deterioration.21 The reactivation of HBV or superposition with other liver diseases will aggravate hepatocyte necrosis, which leads to the release of circulating DAMPs and promotes an inflammatory response. At the same time, during the process of chronic liver disease progression, the body gradually shows cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction (CAID), which will create opportunities for HBV reactivation and bacterial infection, so some HBV-ACLF patients may simultaneously have multiple causes that synergistically promote the development of ACLF.22, 23Among the 420 patients with ACLF in the PREDICT study, 65% had obvious systemic inflammatory triggers, such as bacterial infection and gastrointestinal bleeding, while 35% had no obvious triggers. However, the patients without obvious triggers still had features of systemic inflammation.24 Meanwhile, the PREDICT study showed that inflammation occurs in the progression of acute decompensated cirrhosis to ACLF.25, 26 Evidence from a prospective study also indicates that inflammation severity is the most important predictor of ACLF and gastrointestinal bleeding in acute decompensated patients.27 Wu et al. found that NLR and MLR were associated with the risk of death in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic HBV, where NLR was an independent predictor of progression to ACLF.28 However, the impact of inflammation on HBV-ACLF disease development remains to be further explored.

First of all, for this study, statistical differences were found in age, platelets, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, albumin, prealbumin, ALT, AST, TBil, serum creatinine, PT, INR, PWR, NLR, MLR, and MELD serial scores between the 2 groups (Table 1). Among them, the patients in the death group were older and had lower protein levels, more severe coagulopathy and higher inflammation levels. Platelet levels were higher in the survival group; meanwhile, our previous study found that platelets can effectively predict the survival of HBV-ACLF patients 180 days after plasma exchange.29 The reason may be that platelets are related to liver regeneration, infection, systemic inflammatory response, and immune diseases.30, 31 In addition, serum ALT levels were higher in the survival group, and we speculated that ALT is a protein with enzyme activity synthesized by liver cells. The higher the ALT level, the more sensitive the liver synthesis function will be, which has a certain predictive effect on the liver function of HBV-ACLF patients.

In analyzing the correlation between inflammatory markers and MELD scores, we found that NLR, MLR, SII, PNI, leukocyte count, neutrophil count, and monocyte count were positively correlated with MELD scores, while PWR and lymphocyte count were negatively correlated with MELD scores. This also proves that as the MELD score increases, inflammatory indicator levels also increase, but indicators related to immune function and nutritional synthesis function will continue to decrease.

Next, considering the progress made in the field of predicting ACLF prognosis with inflammatory markers,30, 32 we compared the widely used markers at present. Our findings indicated that NLR, MLR, MELD score, MELD-Na score, and iMELD score were significantly higher in the death group. This validated the results of previous studies.25, 26, 27, 28 In our study, MLR had better statistical significance than NLR, both in relation to MELD score and in the analysis of 90-day mortality factors. Therefore, we further carried out a multivariate analysis of MLR and established a new MLR-iMELD model. The MLR is the ratio of monocytes to lymphocytes. Liver resident macrophages account for more than 80% of the total number of macrophages in the body, and they make a difference in liver fibrosis and inflammatory immune response.32 Macrophages can be activated by various stimuli, such as bacteria, viruses or necrotic tissue. The inflammatory response of the body can trigger the release of monocytes from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood so that monocytes in the blood can differentiate into tissue macrophages to play an immune role.32, 33, 34 Just recently, Niehaus et al. described a subpopulation of lymphocytes, mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, that were markedly reduced in cirrhotic patients, and the number of MAIT cells decreased with declining liver function.35 For patients with ACLF, liver cell necrosis can cause the release of a large number of inflammatory factors, thereby activating the immune inflammatory response in the body and inducing a large number of granulocytes to migrate from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood, giving rise to a significant decrease in the number of peripheral blood lymphocytes.36 Therefore, changes in monocytes and lymphocytes have certain value in evaluating the prognosis of HBV-ACLF patients. The MLR-iMELD model outperformed the MELD series scores in predicting patients’ 90-day survival. Furthermore, patients with high MLR-iMELD scores (≥ –0.33) had a poorer 90-day prognosis.

Limitations

First, this was a single-center observational retrospective study with a relatively small sample size. Second, we included only the baseline data of patients for analysis, so the dynamics of patients were not observed. Third, the assessment of inflammation in our study was based on routine blood tests, so whether other inflammatory biomarkers can better predict prognosis needs to be further explored.

Conclusions

Higher inflammation levels predicted a higher 90-day mortality risk in HBV-ACLF patients. The MLR-iMELD model can better predict the 90-day survival of HBV-ACLF patients than other composite inflammatory indicators. The clinical value of evaluating inflammation-related indicators may provide a valuable supplement for the assessment of disease status in HBV-ACLF patients.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13627516. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. The original data of this study.

Supplementary Table 2. Normality test of baseline data in survival and death groups. Through normality test, it was found that the statistical value of normality test in the baseline data of the 2 groups of patients was < 0.05, so they did not conform to the normal distribution.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Test the extreme outliers in the logistic regression hypothesis. We found that there were 8 observations where the studized residuals were greater than 2 times the SD, but we kept them in the analysis.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Multicollinearity among explanatory variables. Through collinearity diagnosis, we found that all independent variables VIF were less than 5, and the degree of collinearity between independent variables was small.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Box–Tidwell test on variables. A total of 19 items were included in the model analysis in this study, including 9 independent variables: age, MLR, WBC, neutrophil, PLT, albumin, ALT, AST, and iMELD; 9 interaction terms: age*lnage, lnMLR*MLR, lnWBC*WBC, ln neutrophil*neutrophil, lnPLT*PLT, ln albumin*albumin, lnALT*ALT, lnAST*AST, and lniMELD*iMELD; and intercept term (Constant). Therefore, in this study, it is recommended that the significance level should be α = 0.00263 (0.05/19). Based on this significance level, the p-value of all interaction terms in this study is higher than 0.00263, so there is a linear relationship between all continuous independent variables and the logit conversion value of the dependent variable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.