Abstract

Background. Overweight and obesity are the most common high-risk conditions that increase the risk of adverse outcomes during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Dysfunctions in trophoblastic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) contribute to a variety of related pregnancy disorders.

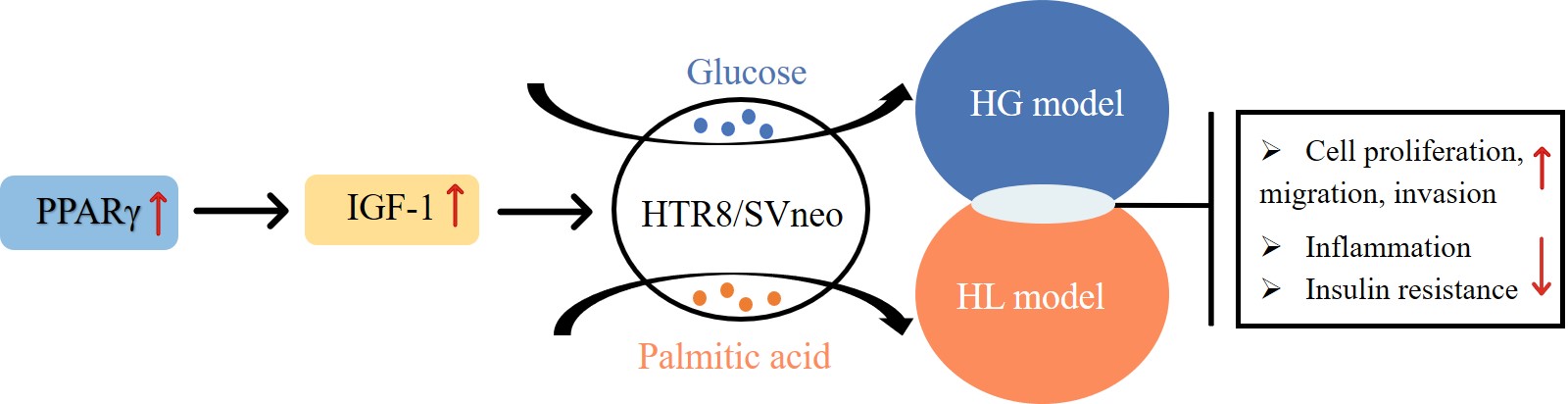

Objectives. This study investigated whether PPARγ influences chorionic trophoblast cell damage induced by high glucose (HG) and high lipid (HL) by regulating insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).

Materials and methods. Human trophoblast HTR-8/SVneo cells were exposed to HG and HL conditions to simulate damaged trophoblasts during pregnancy in vitro. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was used to assess cell proliferation. The Scratch test was used to test cell migration. Cell invasion ability was assessed by Transwell assay. ELISA was used to assess the inflammatory factor levels. Glucose, lactic acid, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels were measured using biochemical kits.

Results. High glucose/HL inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HTR-8/SVneo cells. High glucose and HL increased tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 expression while decreasing IL-10 expression. High glucose and HL decreased glucose uptake and ATP levels. High glucose and HL reduced the expressiofns of PPARγ, IGF-1, insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4. High PPARγ expression promoted cell proliferation, migration, and invasion induced by HG and HL, increased glucose uptake and ATP levels and inhibited inflammation. Low IGF-1 expression inhibited cell proliferation, migration, and invasion under HG and HL conditions, reduced glucose uptake and ATP levels, and increased inflammation. Low IGF-1 expression reversed the effects of PPARγ on HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions.

Conclusions. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma alleviated HTR-8/SVneo cell damage induced by HG and HL by regulating IGF-1, suggesting a potentially effective approach for treating gestational obesity.

Key words: IGF-1, PPARγ, high glucose, high lipid, trophoblast cell injury

Background

Epidemiological studies have shown that gestational obesity affects more than half of pregnancies in developed countries and is associated with obstetric complications and poor outcomes.1 Gestational obesity is associated with various pregnancy complications, including gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, stroke, and venous thromboembolism.2 Currently, dietary and lifestyle interventions for managing maternal obesity during pregnancy have shown limited effectiveness.3 Therefore, further research into the molecular mechanisms underlying gestational obesity is crucial for developing new prevention and treatment strategies.

Obese pregnant women experience a lipotoxic placental environment characterized by increased inflammation and oxidative stress.4 They also exhibit heightened insulin resistance, elevated plasma insulin, leptin, lipids, and potentially proinflammatory cytokines, along with lower plasma adiponectin, thereby increasing the risk of disease later in life.5 Insulin signaling plays a crucial role in regulating cellular glucose uptake and maintaining blood glucose levels. Dysregulation of the insulin signaling pathway in placental trophoblastic cells, including insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1, IRS2, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and glucose transporter (GLUT) 1, can lead to adverse outcomes in the context of obesity during pregnancy.6

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a nuclear transcription factor mainly expressed in adipose tissue. It promotes fatty acid storage in adipose tissue, regulates the expression of adipocyte-secreted hormones, and influences glucose homeostasis.7 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is overexpressed in various types of trophoblasts during pregnancy.8 However, unusually low PPARγ activity has been observed in placental pathology.9 Studies have shown that PPARγ promotes trophoblastic differentiation and supports healthy placental function, potentially improving preeclampsia outcomes.10 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists improve insulin resistance in human trophoblasts HTR-8/SVneo cell models exposed to high glucose (HG).11 Additionally, PPARγ inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and inflammation levels in gestational intrahepatic cholestasis mice and taurocholic acid-treated HTR-8/SVneo cells.12 Despite the known importance of PPARγ in trophoblast function, its precise role and mechanisms in protecting against or mitigating damage caused by HG and high lipid (HL) in HTR-8/SVneo cells are not yet fully understood. Further exploration and investigation are needed to elucidate the specific effects and underlying mechanisms of PPARγ in this context.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a key regulator of mammalian growth and metabolism, plays a crucial role in numerous cellular processes, including growth, differentiation, and transformation. It has become a focal point of research in various vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, angiogenesis, and diabetic vasculitis.13 Previous studies have shown that activation of PPARγ by troglitazone leads to the modulation of IGF-1 gene expression in a dose-dependent manner.14 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha alternative splice variant 4 upregulates IGF-1 in cyclic AMP-regulated transcriptional coactivator 1/mastermind-like 2-positive mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells in a PPARγ-dependent manner.15 MicroRNA (miR)-30a-3p is overexpressed in the placentas of preeclampsia patients, promoting HTR-8/SVneo cell invasion and inhibiting apoptosis by targeting IGF-1.16 However, the roles and mechanisms of PPARγ and IGF-1 in cell damage in HTR-8/SVneo cells exposed to HG and HL remain unclear.

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate whether PPARγ influences HG- and HL-induced HTR-8/SVneo cell damage by regulating IGF-1.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human trophoblasts HTR-8/SVneo cells (AW-CNC496, Abiowell, China) were isolated from PMI-1640 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, USA). The cells were grown in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. As previously described,17 low glucose (5.5 mmol/L glucose) is a typical condition for cell growth, mimicking normal physiological conditions, and an HG/HL cell model was constructed. Before treatment with HG/HL, the cells were treated with low glucose (5.5 mmol/L glucose) for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed, and the medium was changed to HG (25 mmol/L glucose) and/or HL (0.4 mmol/L palmitic acid). The control group cells were cultured with low glucose for 24 h.

Cell transfection

HTR-8/SVneo cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates for 24 h. As previously described,18 the cells were transfected with either the pcDNA3.1-PPARγ overexpression vector (2 μg) or pcDNA3.1-negative control (NC) (2 μg), and small interfering RNA (si)-NC (20 nM) or si-IGF-1 (HG-Si000875, Honorgene, China) (20 nM), using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The sequence of si-IGF-1 used was 5’-ATTTCTTGAAGGTGAAGATG-3’. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

Cell Count Kit-8 detection

As previously described,19 the CCK-8 assay was used to measure cell viability. After 48 h of cell incubation, the CCK-8 reagent (AWC0114a, Abiowell, China) was added for 3 h. Cell viability was analyzed at 450 nm using a microplate reader (MB-530, HEALES).

Scratch test

A 20 μL pipette tip was used to form a wound through a single layer of cells. After removing the scratched cells, serum-free RPMI-1640 medium was added. Continuous images were captured under an optical microscope at 0, 24, and 48 h. Wound healing progress was assessed by measuring the width of the scratch.

Transwell assay

The Transwell membrane was pre-coated with 50 μL of 100% Matrigel (Corning) and then dried at 37°C. Cells were added to the top chamber with serum-free medium, whereas a complete medium containing 10% FBS was added to the bottom chamber. Following a 24-h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells in the top chamber were removed using a cotton swab. Invaded trophoblast cells on the Transwell membranes were fixed in cold ethanol for 20 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 5 min, and counted using an inverted microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

As previously described,20 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (CSB-E04740h, CSB-E08053h, CSB-E04638h, CSB-E04593h, CUSABIO, Wuhan, China) were used to measure levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-10.

Glucose uptake assay

Glucose uptake by cells was determined using the cell glucose colorimetric assay kit (A154-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). As previously described,21 1×107 pretreated cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The cell suspension was removed and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded, leaving the cell pellet. The pellet was incubated with 250 μL of working solution at 37°C for 10 min. The results were read and analyzed at 505 nm using a microplate reader.

Adenosine triphosphate levels

Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels were determined using the ATP assay kit (A095-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). As previously described,22 100 μL of cell lysate was mixed with 100 μL of the ATP reaction mixture and incubated for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 636 nm using a microplate reader.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRlzol reagent (15596026, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcription kits (CW2569, CWBIO, China). PCR amplification was performed with UltraSYBR mixture (CW2601, CWBIO, China) using the PIKOREAL96 fluorescent quantitative PCR system by ThermoFisher. β-actin mRNA was used for normalization, and relative expression was determined using the 2–ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Western blot

RIPA buffer (AWB0136, Abiowell, China) was added, and the cell supernatant was collected after centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein quantification kit. Subsequently, proteins were isolated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was then blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1.5 h. Next, the membrane was incubated with a primary antibody (Table 2). After washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with a secondary antibody for 2 h. The ChemiScope6100 system (CLiNX) captured the chemiluminescent signal from the membrane and produced a digital image of the protein bands. Image band densities were then calculated using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.5, USA). Beta-actin was used as the internal reference.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Data are presented as median (max and min) (n = 6). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons between the 2 groups, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis H test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test, was applied for multiple group comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Supplementary Tables 1–5 contain statistical analysis results corresponding to the figures.

Results

High glucose and HL inhibited HTR-8/SVneo cell proliferation, migration, and invasion II rzedu

To investigate the effects of HG and HL on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, CCK-8, scratch assay, and Transwell assay were performed. The results showed that HG and HL inhibited cell proliferation (Figure 1A), cell migration (Figure 1B), and cell invasion (Figure 1C). High glucose and HL had superimposed effects. Compared with the HG group, HL further reduced cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (Figure 1A–C). Our results suggested that HG and HL inhibited HTR-8/SVneo cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Gestational obesity is a complex state involving multiple environmental changes, and the environment of HG and HL better simulates the pathological state of gestational obesity.23, 24 Therefore, HG plus HL cell models were constructed for subsequent in vitro studies.

High glucose and HL promoted cellular inflammation

Next, the effects of HG and HL on inflammation levels were further investigated. Proinflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 play important roles during pregnancy in obese women.25 CircSESN2 exacerbates HG-induced HTR-8/SVneo cell injury by binding to IGF2BP2 and increasing TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 protein expressions.26 Our results showed that HG and HL upregulated TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expressions while downregulating IL-10 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells (Figure 2A). Additionally, HG and HL decreased cellular glucose uptake and ATP levels (Figure 2B). PPARγ, encoded by PPARG, is involved in angiogenesis, metabolic processes, anti-inflammatory responses, and reproductive development.27 PPARγ promotes HTR-8/SVneo cell proliferation and migration while inhibiting inflammation.28 IGF-1 is an important fetal growth factor, and LncRNA-SNX17 decreases miR-517a expression, thereby increasing IGF-1 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells and enhancing cell proliferation and invasion.29 Maternal obesity during pregnancy creates a proinflammatory environment that disrupts the response of beta cells to pregnancy endocrine signals, induces insulin resistance, and inhibits glucose uptake.30 Klotho inhibits IGF-1 and insulin signaling molecules (IRS1, IRS2, and GLUT4) expression and glucose uptake in HG-induced HTR-8/SVneo cells, thereby decreasing cell viability.31 Our results showed that HG and HL inhibited the expression of PPARγ, IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 (Figure 2C). Overall, our findings suggest that HG and HL promote the inflammatory response in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

Upregulation of PPARγ inhibited cellular inflammatory response induced by HG and HL

To further explore the effect of PPARγ on inflammation under HG and HL conditions, HTR-8/SVneo cells were overexpressed with PPARγ. QRT-PCR results showed that oe-PPARγ increased PPARγ expression in cells (Figure 3A). Oe-PPARγ enhanced proliferation under HG and HL conditions (Figure 3B). Oe-PPARγ decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expressions under HG and HL conditions, while increasing IL-10 levels (Figure 3C). Additionally, oe-PPARγ increased glucose uptake capacity and ATP levels in cells under HG and HL conditions (Figure 3D). Oe-PPARγ upregulated levels of PPARγ, IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 in cells under HG and HL conditions (Figure 3E). In conclusion, high PPARγ expression reduced cellular inflammation levels under HG and HL conditions.

IGF-1 knockdown inhibited the cellular inflammatory response induced by HG and HL

Next, the effects of IGF-1 on HTR-8/SVneo cell inflammation under HG and HL conditions were investigated. QRT-PCR results showed that si-IGF-1 downregulated IGF-1 expression in cells (Figure 4A). Si-IGF-1 inhibited cell proliferation under HG and HL conditions (Figure 4B). Si-IGF-1 increased TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in cells under HG and HL conditions while decreasing IL-10 expression (Figure 4C). Additionally, si-IGF-1 reduced glucose uptake capacity and ATP levels in cells induced by HG and HL (Figure 4D). Si-IGF-1 downregulated the levels of PPARγ, IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 in HG and HL-induced cells (Figure 4E). In conclusion, low IGF-1 expression promoted HG and HL-induced cellular inflammatory responses.

PPARγ-mediated IGF-1 influenced the cellular inflammatory response and proliferation, migration, and invasion induced by HG and HL

The study further clarified whether PPARγ mediated IGF-1 to influence the inflammatory response and proliferation, migration, and invasion of HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions. PPARγ overexpression increased PPARγ and IGF-1 levels in cells, whereas si-IGF-1 downregulated IGF-1 levels (Figure 5A). Oe-PPARγ enhanced the proliferation capacity of HG and HL-induced cells, whereas si-IGF-1 inhibited cell proliferation (Figure 5B). Si-IGF-1 disrupted the promotion of HG- and HL-induced migration and invasion by oe-PPARγ, inhibiting these processes (Figure 5C,D). Oe-PPARγ downregulated TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression in HG and HL-induced cells, while upregulating IL-10 expression. Compared with the oe-PPARγ + si-NC group, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression was increased in the oe-PPARγ + si-IGF-1 group, whereas IL-10 levels were decreased (Figure 6A). Glucose uptake capacity and ATP levels were increased in the oe-PPARγ + si-NC group compared with the oe-NC + si-NC group. Si-IGF-1 inhibited cellular glucose uptake and ATP levels (Figure 6B). PPARγ, IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 levels were upregulated in the oe-PPARγ + si-NC group compared with the oe-NC + si-NC group. In contrast, IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 levels were decreased in the oe-PPARγ + si-IGF-1 group compared with the oe-PPARγ + si-NC group (Figure 6C). In conclusion, PPARγ promoted proliferation, migration, and invasion but reduced the cellular inflammatory response by upregulating IGF-1 under HG and HL conditions.

Discussion

We found that PPARγ overexpression reversed the effects of HG and HL on HTR-8/SVneo cells. PPARγ overexpression enhanced the cell proliferation, migration, and invasion induced by HG and HL, promoted glucose uptake and ATP levels, and reduced the inflammatory response. Knockdown of IGF-1 reduced the cell proliferation, migration, and invasion induced by HG and HL, inhibited glucose uptake and ATP levels, and promoted the inflammatory response. Knocking down IGF-1 reversed the effects of PPARγ overexpression on cells induced by HG and HL.

Diets containing HL and HG could lead to overweight/obesity.32 Obesity in pregnant women is associated with impaired placental function, resulting in restricted development of placental blood vessels and fetal developmental disorders. Diallyl trisulfide reduces the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in the placenta, promotes the expression of IL-10, and improves the reproductive performance of obese pregnant mice.33 Palmitic acid increases TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in the placenta, inducing placental inflammation during pregnancy in mice.34 The development of chorionic trophoblast cells, which comprise the outer layer of the placenta, is crucial for a successful pregnancy and plays a role in various pregnancy disorders, including gestational obesity.35 Studies have shown that miR-134-5p inhibits FOXP2 expression, promotes TNF-α and IL-1β expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG conditions, and inhibits IL-10 expression, thereby exacerbating gestational diabetes.20 SESN2 upregulates TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β expression, exacerbating damage to HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG conditions.26 We found that PPARγ decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions while increasing IGF-1 and IL-10 levels. IGF-1 knockdown played an opposite role in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions, promoting TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression while inhibiting IGF-1 and IL-10 levels. Furthermore, IGF-1 knockdown hindered the protective effect of PPARγ in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions. Studies have shown that naringin upregulates IR-α and IGF1R expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG conditions, increasing glucose uptake, cell proliferation, and migration.6 Combined treatment with monounsaturated fatty acids can prevent palmitic acid-induced apoptosis of HTR-8/SVneo cells and reduce caspase 3/7 activity.36 MiR-137 inhibits HTR-8/SVneo cell viability and migration under HG and HL conditions by downregulating FNDC5.37 Blocking CYP1B1 inhibits HTR-8/SVneo cell proliferation, migration, and invasion under HG conditions.38 Nesfatin 1 alleviates damage to HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG/HL conditions and improves cell viability.17 Our results showed that PPARγ promoted proliferation, migration, and invasion of HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions, whereas IGF-1 knockdown reversed all of the above effects and inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion. Our results were consistent with previous studies.

During normal pregnancy, the mother develops hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia to provide nutrients to the fetus for growth and development.39 Obesity during pregnancy may incorrectly induce or exaggerate metabolic and physiological changes and contribute to the risk of metabolic diseases for both the mother and the developing baby.40 TDAG51 reduces blood glucose levels, enhances serum insulin, and reduces glucose and insulin resistance, improving gestational diabetes.23 Studies have shown that β-carotene upregulates GLUT3, GLUT4, and IRS1 levels in insulin-resistant HTR-8/SVneo cells and increases glucose uptake to improve gestational diabetes mellitus.41 ABHD5 promotes HG-induced expression of GLUT4, insulin receptor (INSR), IRS1, and IRS2 in HTR-8/SVneo cells to improve insulin resistance.42 Klotho deletion reduces HG-induced cell viability, insulin signaling molecules (INSR-α, INSR-β, IRS1, IRS2, and GLUT4) expression, and glucose uptake while improving insulin resistance.31 We found that the PPARγ promoted glucose uptake and increased ATP levels in HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions, increasing IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4 expression. IGF-1 knockdown reversed the PPARγ effect on HTR-8/SVneo cells under HG and HL conditions, reducing glucose uptake and ATP levels and inhibiting the expression of IGF-1, IRS1, IRS2, GLUT1, and GLUT4. Therefore, PPARγ might emerge as a potential target for treating obesity in pregnancy.

Limitations

Certain limitations in this study should be taken into account when designing future studies. Because uterine smooth muscle cells,43 endothelial cells,44 and oocytes45 influence the outcomes of obese pregnancy, further exploration into the potential molecular mechanisms of PPARγ in these cells is necessary. Successful pregnancy depends critically on well-regulated migration and invasion of placental villus trophoblasts.46 The placenta is essential for nutrient and waste exchange between mother and fetus during pregnancy.47 Obesity in pregnant women increases hypoxia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the placenta.48 Adipocyte-derived exosome NOX4 induces senescence of HTR8/SVneo cells, inhibiting cell proliferation and migration, and induces premature placental aging in obese pregnant mice.49 Future studies should explore the potential molecular mechanisms of PPARγ in obese pregnant mice to strengthen the conclusions of this study based on these cell experiments. In this study, the sample size of the cell experiment was very limited. Future studies should aim to expand the sample size for exploration.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that PPARγ alleviates damage to HTR-8/SVneo cells induced by HG and HL by regulating IGF-1. These findings could offer new insights into potential strategies for the clinical treatment of gestational obesity.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)