Abstract

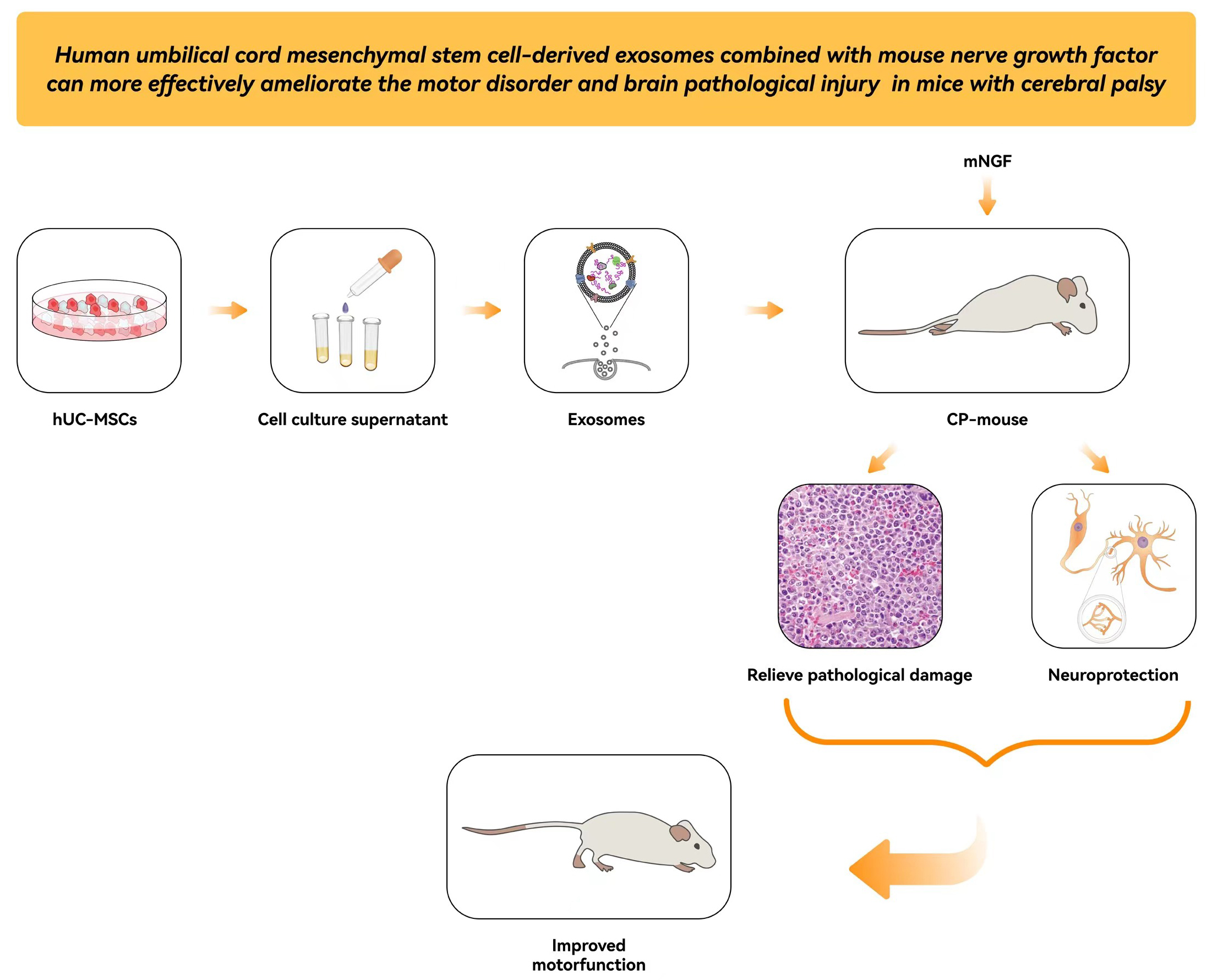

Background. Cerebral palsy (CP) is a neurodevelopmental disorder and motor disorder syndrome. It has been confirmed that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and mouse nerve growth factor (mNGF) can repair brain tissue damage and nerve injury; however, exosomes derived from healthy cells may have a comparable therapeutic potential as the cells themselves.

Objectives. The purpose of this study was to explore the improvement effect of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (hUC-MSCs)-derived exosomes on a CP model and determine whether there is a synergistic effect when combined with mNGF.

Materials and methods. Exosomes were isolated from hUC-MSCs and examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), particle size and western blot (WB). A total of 38 BALB/c mice (male, postnatal day 6 (PND6)) were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham group, CP group, CP-exo group, CP-mNGF group, and CP-exo-mNGF group. Hypoxic induction after unilateral common carotid artery ligation combined with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infection was used to construct the CP model. Pathological damage to neuron tissue and synaptic structures in the hippocampus was confirmed using light microscopy after hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining and TEM, respectively. Survival of neurons was evaluated using Nissl staining. Western blot was applied to monitor PSD-95 and synaptophysin (SYN) protein levels.

Results. This study indicated that exosomes released by hUC-MSCs ameliorated brain damage and synaptic structure destruction in CP mice induced by hypoxic ischemia and LPS infection. When combined with mNGF, there was more effective improvement. In the CP group, neuronal function was severely impaired; however, hUC-MSCs-derived exosomes and mNGF improved it. PSD-95 and SYN proteins were presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins, respectively. Interestingly, the PSD-95 and SYN protein levels were significantly lower in the CP mice, but with the addition of hUC-MSCs-exosomes or mNGF, they increased significantly, especially in the CP-exo-mNGF group.

Conclusions. The nerve function injury in CP can be improved the most when hUC-MSCs-derived exosomes are combined with mNGF through intraperitoneal (ip.) administration.

Key words: exosome, human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, cerebral palsy, mouse nerve growth factor

Background

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a nonprogressive and permanent neurodevelopmental disorder syndrome caused by various risk factors. It occurs in 2–3 out of 1,000 live births and has multiple etiologies that result in brain injury, affecting movement, posture and balance.1 Additionally, some symptoms become more obvious over time. Although no definite method exists to date that cures CP, supportive treatment and drug therapy may alleviate CP symptoms to a certain extent and improve the patient’s motor skills and functional ability. The primary treatment for CP is rehabilitation training, including intramuscular onabotulinum toxin A injections, systemic and intrathecal muscle relaxants, selective dorsal rhizotomy, and physical and occupational therapies.1, 2 However, all these treatment measures have the drawbacks of slow action and possible regression after the intervention is discontinued.1, 2 Therefore, alternative or complementary therapeutic measures are urgently needed. Studies have confirmed that cerebral ischemia–hypoxia in the perinatal period or up to 1-year postpartum is the main cause of CP. Inflammation is now believed to be a key component in the development of CP.3 In this study, a neonatal mouse model of CP was established using combined hypoxia–ischemia and inflammation to create an injury that better mimicked the neurodegeneration seen in human CP.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a type of multipotent stem cell originating from the mesenchyme that possess various crucial biological characteristics. Their main features include multipotency, self-renewal, immunomodulation, and secretion of factors.4 Additionally, the antiapoptotic, paracrine and multidirectional ability of MSCs to differentiate has driven their current evaluation in translational research and clinical trials for treating many common diseases, including neurological disorders involving central nervous system (CNS) structures, such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury.5 Mesenchymal stem cells can exert their effects through neuroprotection, neural regeneration, anti-inflammatory effects, promotion of angiogenesis and vasculogenesis, and immunomodulation.5, 6 Human umbilical cord MSCs (hUC-MSCs) are somatic stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood that have self-renewal and multidirectional differentiation potential. They can be used as a cell source for treating many diseases and repairing tissue damage.7, 8 Compared with other MSCs, hUC-MSCs have gained the attention of researchers for tissue injury repair because of their low cost, minimal invasiveness, convenient isolation, large cell content, high gene transfection efficiency, low immunogenicity,9 and lack of ethical issues. Therefore, in recent years, hUC-MSCs have gradually become the focus of somatic stem cell research. Increasing evidence shows that hUC-MSCs exert their therapeutic effects mainly through extracellular vesicles (EVs) produced by paracrine actions. Extracellular vesicles have emerged as a new promising alternative to whole-cell therapy because of their lower immunogenicity and tumorigenicity and easier management.10 The MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-exos) have been used as a therapeutic approach in treating several diseases, such as neurological, cardiovascular, liver, kidney, and bone diseases, as well as cutaneous wounds, inflammatory bowel disease, cancers, infertility, and other disorders. Furthermore, besides treating CNS diseases, MSC-exos play a role in mediating anti-inflammation, increasing neuronal growth, maintaining the number of neurons, and promoting neurite remodeling.11, 12, 13, 14 Their clinical use might provide substantial advantages compared with live cells due to their potential to reduce undesirable side effects after application, including infusional toxicity, uncontrolled cell growth and possible tumor formation.15 However, the role of hUC-MSC-exosomes (hUC-MSC-exos) in CP is unclear. Hence, this study hypothesized that increasing neuronal growth and alleviating white matter damage using hUC-MSC-exos may be responsible for this effect.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) in mice is synthesized through a multistep process within cells. Initially, the NGF gene, encoded in the mouse genome, undergoes transcription in the cell nucleus, resulting in the production of messenger RNA (mRNA). This mRNA is then translated into the precursor protein of NGF. The precursor protein undergoes post-translational modifications, such as cleavage and glycosylation, ultimately yielding mature NGF protein. Once synthesized, NGF is secreted from cells into the extracellular space.16, 17 It promotes neuronal survival and growth, supports nerve regeneration, regulates synaptic plasticity, and modulates pain perception.18 These roles highlight NGF’s importance in maintaining the structure and function of the nervous system in mice. The mNGF is commonly used in nerve injury treatment.19 Some researchers have reported that mNGF was effective in treating CNS injury and developmental disorders in children.20 Feng et al. found exogenous NGF have great potential for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment, preventing the impaired hippocampal cytoarchitectures.21

Currently, treatment options for CP are limited, and the therapeutic effects of hUC-MSC-exos in CP remain to be explored. It has yet to be investigated whether combination therapy with mNGF could yield better therapeutic outcomes.

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effects of hUC-MSC-exos on mice with CP and attempted to determine whether the combination of hUC-MSC-exos and mNGF has a better therapeutic effect for mice with CP.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and exosome preparation

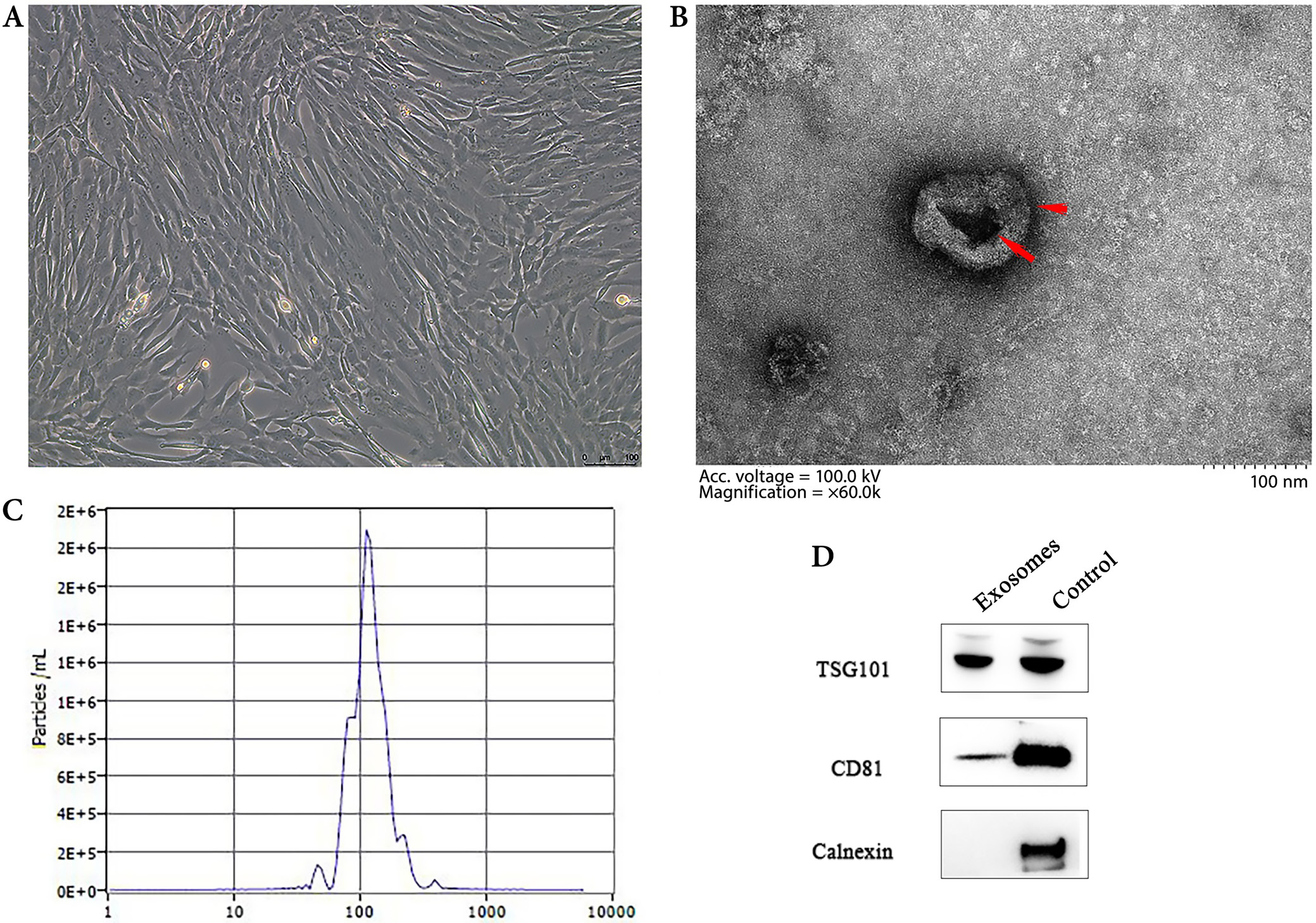

Exosomes were isolated from hUC-MSCs, collected by supercentrifugation22 and examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), particle size and western blot (WB) analysis. Frozen hUC-MSCs (#CP-CL11; Procell, Wuhan, China) underwent cell resuscitation and were incubated in a culture medium at 37°C. The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and digested with trypsin. Next, they were cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Waltham, USA) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco). When the cell confluency reached 80%, the conditioned media were harvested and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.45-μm filter membrane (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA), and the filtrate was collected. The filtrate was moved to a new centrifugal tube, an overspeed rotor was selected, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 100,000 g at 4°C for 70 min. The supernatant was removed and resuspended in 10 mL of precooled 1 × PBS. The overspeed rotor was selected and centrifuged again at 4°C at 100,000 g for 70 min. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and used for further experiments. Western blot analysis was performed to detect the expression levels of the known exosomal markers CD9 (Abcam, Cambridge, USA) and CD81 (Abcam), as well as tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101; Abcam). The exosome morphology was observed using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi HT-7700; Hitachi Tokyo, Japan), and the exosome particle size analysis was conducted using a nanoparticle tracking analyzer (NTA; Particle Metrix GmbH, Inning am Ammersee, Germany). The exosomes were either stored at −80°C or used immediately for subsequent experiments.

Animals and groupings

The study was carried out in accordance with the Chinese National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Gansu Province People’s Hospital (Lanzhou, China; approval No. 2022-007). A total of 38 male BALB/c mice on postnatal day 6 (PND6), along with their mothers, were obtained from Chengdu Dashuo Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) and housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) laboratory at the Lilei Biomedicine Experiment Center (Chengdu, China). The mice were kept on a normal chow diet under pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle, at a temperature of 22°C ±1°C and a humidity of 40–60%.

The mice were randomly divided into 2 groups: the sham group (n = 6) and the CP group (n = 32). The experimental CP model was induced as described in a previous study23 by hypoxic conditions following unilateral common carotid artery ligation combined with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infection. After the induction, the mice were randomly divided into 4 subgroups, each containing 8 mice: the CP group; the CP-exosomes (CP-exo) group, in which the mice were intraperitoneally (ip.) injected with 125 µg of exosomes; the CP-mNGF group, in which the mice received ip. injections of mNGF at a dose of 5 μg/kg/day for 14 consecutive days; and the CP-exosome-mNGF (CP-exo-mNGF) group, in which the mice were ip. injected with both 125 µg of exosomes and 5 μg/kg/day of mNGF for 14 days. This protocol was based on the research by Sun et al. and Gao et al.24, 25

The health and behavior of the mice were monitored weekly. During the experiment, 2 mice, 1 from both the CP group and the CP-mNGF group, died. After 14 days of intervention (P23), all surviving mice had gained weight and undergone a neurological deficit assessment. The mice were then deeply anesthetized with an ip. injection of 0.3% sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and sacrificed by decapitation; their brains were then rapidly removed. The hippocampus tissues were dissected on ice, immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C for subsequent experiments.

Behavioral test

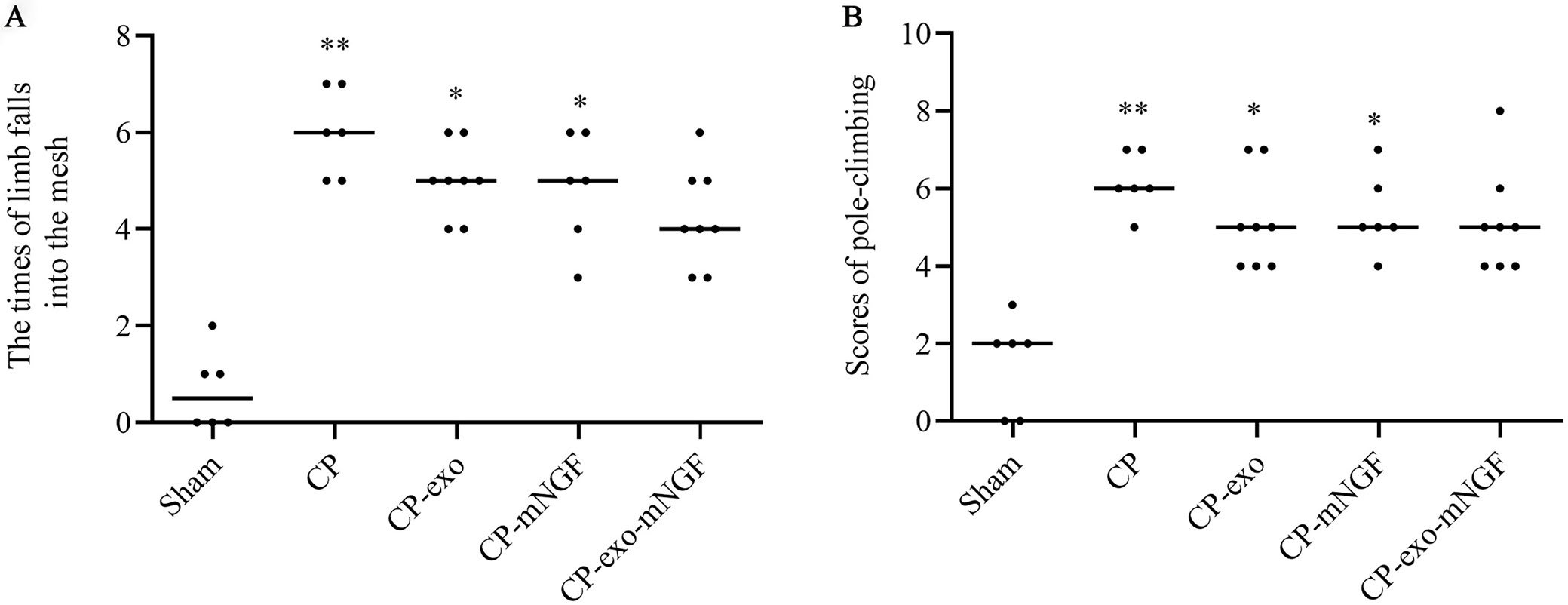

The behavioral evaluation was performed on the 14th day after the intervention using a horizontal grid test and pole-climbing test.26, 27 The horizontal grid test was designed to evaluate the grasping ability of the mice’s limbs. The pole-climbing experiment was employed to evaluate the motor coordination ability of the mice.

A double-blind method was employed in the behavioral experiments to ensure objectivity. The frequency of falls during the horizontal grid test and the results of the pole-climbing test were assessed by a third party who was unaware of the purpose of the experiment. Subsequently, statistical analysis was conducted on these measurements.

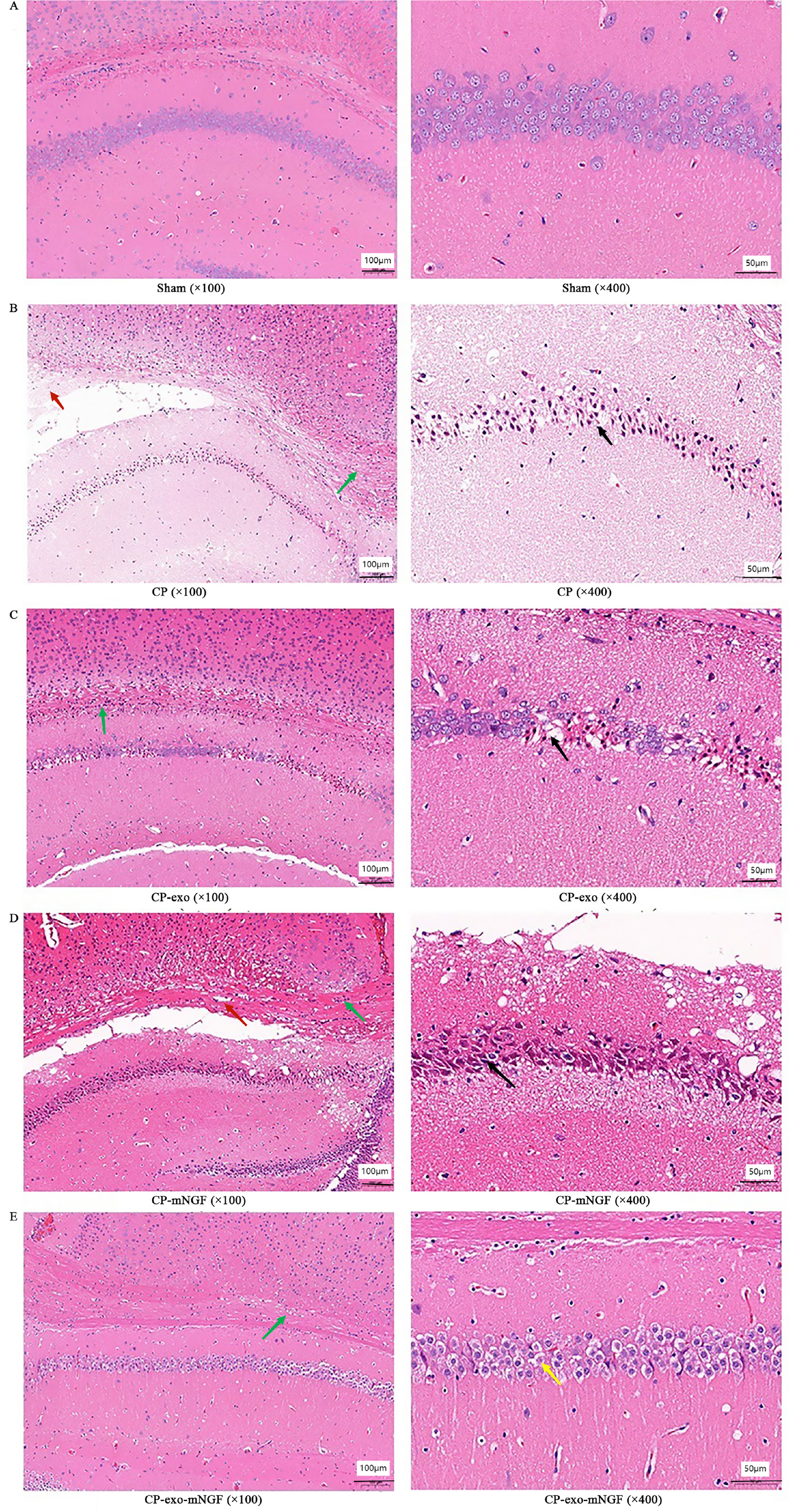

Evaluation of brain histological pathology using hematoxylin–eosin staining

The fixed tissue was dehydrated using an automatic dehydrator, embedded and sectionalized. All the aforementioned actions were performed according to the standard operating procedure of pathological examination (dehydration, trimming, embedding, slicing, dyeing, sealing, etc., and finally microscopic examination). A panoramic 250 digital section scanner (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary) was used for image collection. Specific lesions were obtained at different magnification factors (×40, ×100 and ×400).

Survival of neurons examined using Nissl staining

The preparation of tissues for Nissl staining was based on the methods described by Xu et al.28 Transverse slices were stained with 1% cresol purple for Nissl staining, according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Cells positive for Nissl in the anterior horns were identified as motor neurons, following previously established methods.29

Protein detection in mouse brain tissue

The brain samples were taken out and put in 2-mL grinding tubes, and then 3-mm steel balls and radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer were added to each tube and placed in a high-speed and low-temperature tissue-grinding instrument (−20°C, grinding 4 times, 60 s each time). The samples were taken out and placed in a refrigerator at 4°C for 30 min for cracking. After 30 min, the samples were taken out and centrifuged at 6,761.66 g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Western blot assay was used to detect proteins. Equal amounts of protein extracts (50 μg) were separated with 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS−PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Then, the membranes were blocked and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-PSD-95 (1:2,000, #AF5283; Affinity, Cincinnati, USA), rabbit anti-SYN (1:2,000, #AF0257; Affinity) and rabbit anti-β-actin (1:100,000, #AC026; ABclonal, Wuhan, China) antibodies. The following day, the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H + L) secondary antibody (1:5,000, #s0001; Affinity) for 2 h at room temperature. The proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents purchased from Millipore (Billerica, USA). Analysis of the results was performed using ImageJ software (National Intitutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, USA). All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using SPSS v. 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). All data are presented as medians and min–max range. Due to concerns about the reliability of using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a sample size smaller than 10, non-parametric tests were employed to analyze the data. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare differences among multiple groups, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons between groups. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation and identification of hUC-MSCs-exos

Previous studies have suggested that hUC-MSCs could repair damaged tissues.30 The purchased cells were cultured and passed on (Figure 1A), and hUC-MSCs-exos were obtained using supercentrifugation. Transmission electron microscopy demonstrated that the exosomes had a typical bilayer membrane vesicle structure (Figure 1B). The NTA results showed a diameter distribution average of 123.8 nm (Figure 1C). The highly studied specific markers TSG101 and CD81 expressed positively (Figure 1D). These results suggest that the isolated substances could be identified as exosomes.

hUC-MSCs-exos ameliorated motor function in mice with CP

In this study, the balance and motor functions of mice with CP were tested using pole-climbing experiments and the horizontal network test. Following experimental modeling, except for the sham group, most animals in the model group moved autonomously but could not extend their left 2 limbs. Some animals exhibited weak movement in the left limbs and moved in a sideways circle. The frequency of limbs falling into the mesh or the scores from the pole-climbing experiments in mice with CP were significantly higher than those in the sham group (Figure 2, Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Kruskal–Wallis test, all p < 0.001), indicating that there was successful construction of the CP model. The horizontal grid test showed a gradual decrease in the frequency of limbs falling into the mesh in the CP-exo, CP-mNGF and CP-exo-mNGF groups compared to the CP group, with a significant improvement noted in the CP-exo-mNGF group (p = 0.02, Table 3); however, there was no statistical significance after being adjusted with Bonferroni correction. This suggests that the combined treatment of hUC-MSC-exos and mNGF could significantly improve motor disorders in mice with CP. The weight of the experimental animals decreased, except in the sham group, with the least weight loss observed in the CP-exo-mNGF group. Furthermore, the weight gain of the mice in the CP-exo-mNGF group was significantly different from that in the CP group.

Mouse nerve growth factor combined with hUC-MSC-exos treatment alleviated the pathological damage to the mouse brain

The pia mater was found to be intact using a light microscope (Olympus BX53; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan), with no obvious inflammatory exudation in any group. As shown in Figure 3, compared with the sham group, the pathological changes in the brains of the mice in the CP group, including patchy necrosis, nerve fiber demyelination, glial cell proliferation in the white matter area, and pyramidal cell necrosis in the hippocampus area, were consistent with the characteristic pathological changes in a brain tissue ischemia and hypoxia model, suggesting that the experimental modeling was successful. However, the degree of pathological changes was different in the brain tissues of mice in the CP, CP-exo, CP-mNGF, and CP-exo-mNGF groups. Patchy necrosis was only found in the CP group (83.3%; 5/6) but not in other groups (χ2 = 27.356, p < 0.001). However, demyelination of nerve fibers in the white matter region was identified in the CP, CP-exo and CP-mNGF groups (83% (5/6), 1/8 (12.5%) and 3/6 (50%), respectively). This phenomenon was not found in the CP-exo-mNGF group (χ2 = 17.516, p = 0.02). Glial cell proliferation between nerve fibers was observed in the CP, CP-exo, CP-mNGF, and CP-exo-mNGF groups (83% (5/6), 87.5% (7/8), 83.3% (5/6), and 75% (6/8), respectively), but no differences were found between groups (χ2 = 0.446, p > 0.05). The decreased proportion of pyramidal cell necrosis observed in the hippocampus area in the CP-mNGF and CP-exo-mNGF groups was greater than in the CP group (50% (3/6) and 50% (4/8) vs 100% (6/6), χ2 = 4.00, p = 0.046; χ2 = 4.20, p = 0.040). Compared with the CP group, there was less pathological damage in the CP-mNGF and CP-exo-mNGF groups, and significantly fewer pathological changes were found in the CP-exo-mNGF group. This suggests that mNGF and mNGF-exos could improve pathological damage in CP, while mNGF-exos could improve it more significantly.

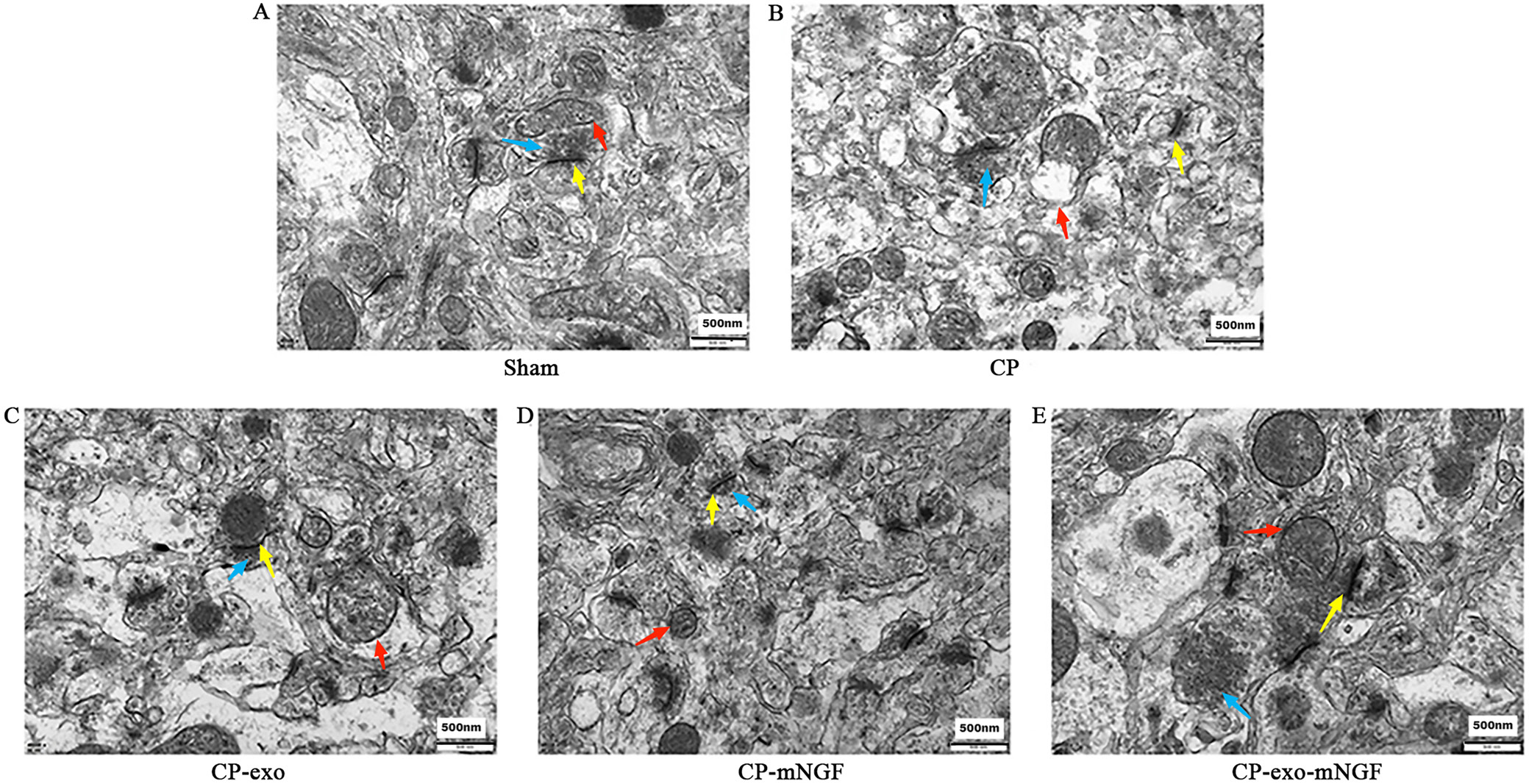

mNGF combined with hUC-MSCs-exos treatment improved the synaptic structure in mice with CP

Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the synaptic structures, comprising presynaptic membranes, postsynaptic membranes and synaptic clefts, were well preserved and abundant in the sham group. In contrast, the CP group exhibited significant dissolution of brain tissue structure and blurring of ultrastructures, with few remaining synapses. In the CP-exo and CP-mNGF groups, some regions showed dissolution, but the synaptic structures remained abundant and clear. The CP-exo-mNGF group displayed synaptic structures similar to those of the sham group (Figure 4), highlighting the beneficial effects of the combined treatment on synaptic integrity in the CP models. Neuronal function was severely impaired in mice with CP but could be recovered using hUC-MSCs-exos, and the effect was better when hUC-MSCs-exos were combined with mNGF.

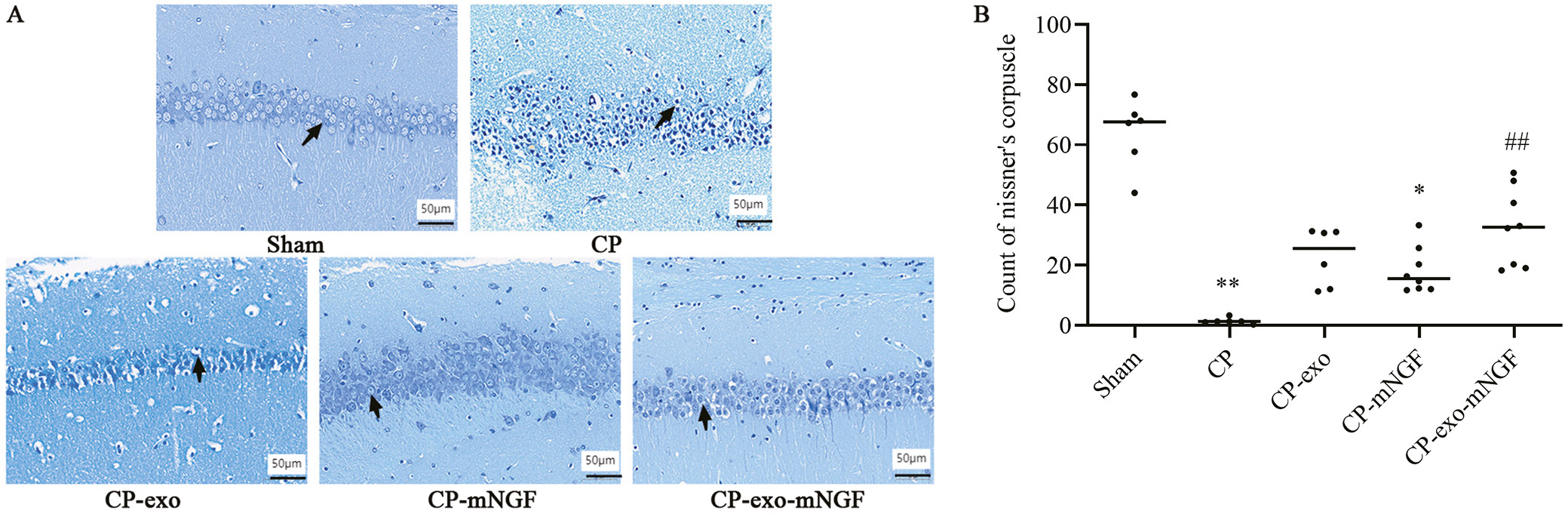

Nissl bodies, a marker of the functional state of neurons, were counted in images at ×400 magnification (Figure 5A). Compared to the sham group, the number of Nissl bodies in the hippocampal pyramidal cells of the mice in the CP group was significantly lower (67.67 (44.00, 76.67) vs 1.33 (0.33, 3.33), Kruskal–Wallis test, H = 4.815, p < 0.001 (Table 5)). In the CP-exo-mNGF group, the number of Nissl bodies was significantly higher than in the CP group, indicating recovery of neuronal function (32.66 (18.33, 50.67) vs 1.33 (0.33, 3.33), Kruskal–Wallis test, H = –3.442, p < 0.001, adjusted p = 0.006 (Table 5)).

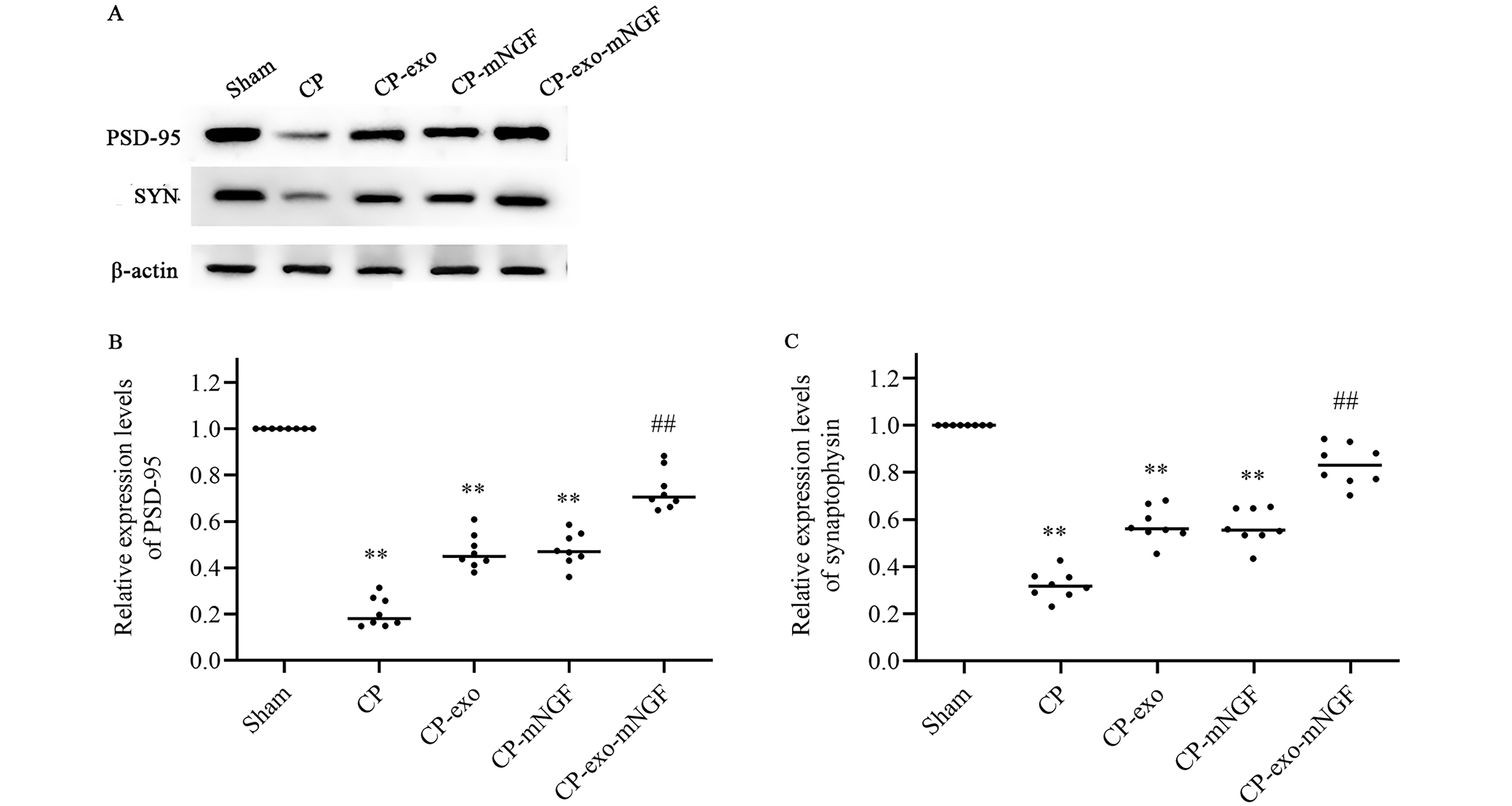

PSD-95 and SYN protein levels were upregulated after hUC-MSCs-exos or mNGF treatment

The expression levels of PSD-95 and SYN proteins in the brain tissues were assessed using WB analysis. The expression levels in the CP group were significantly lower than in the sham group (Kruskal–Wallis test, PSD 95: CP vs sham, H = 32.000, p = 0.000; SYN: CP vs sham, H = 32.000, p = 0.000 Figure 6B,C, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9), but they were significantly higher in the CP-exo-mNGF groups compared to the CP group (PSD-95, 0.70 (0.065, 0.88) vs 0.16 (0.15, 0.27); SYN, 0.83 (0.70, 0.94) vs 0.32 (0.23, 0.43), all p < 0.001, Table 8, Table 9).

Discussion

Cerebral palsy is a permanent motor disorder that results from brain injury and neuroinflammation during the perinatal period. Current therapeutic options for CP are limited. The MSC-exos have demonstrated potential as therapeutics, not only due to their intrinsic properties but also because they are good at crossing epithelial barriers, similar to their parent cells.31 As CP occurs within 1 month before or after birth, neonatal pups were selected as subjects in this study. To investigate the mechanism of CP, a compound CP model of hypoxic induction after unilateral common carotid artery ligation combined with LPS infection was adopted to simulate the pathological changes in the brain after CP.23 In this study, the horizontal grid test and pole-climbing test results indicated that hUC-MSC-exos, especially combined with mNGF, were beneficial for the recovery of motor function, irrespective of the ability of limb grasp or motor coordination. White matter injury is a structural injury that leads to a slowing down or interruption of nerve conduction velocity and damage to cortical and subcortical neurons, resulting in cognitive deficits and intellectual development disorders.32, 33 In this study, the ability of hUC-MSC-exos to improve cerebral injury in mice with CP was assessed, and pathological evidence was obtained.

Treatment with hUC-MSC-exos alone or in combination with mNGF significantly reduced the demyelination of nerve fibers and necrosis of pyramidal cells in the hippocampus area. Demyelination and cell necrosis are common neuropathological features in patients with CP and are closely associated with motor impairments and other clinical symptoms. This finding suggests that hUC-MSC-exos, either alone or combined with mNGF, may exert therapeutic effects through neuroprotective actions or by providing anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects. The hippocampus plays a crucial role in memory processing, converting short-term to long-term memories, so neuroprotective therapies targeting this region are essential. McDonald et al. confirmed that the hippocampus was particularly vulnerable to neonatal hypoxic–ischemic brain injury, mediated through significant neuroinflammation.34 However, clinically, frequently used therapeutic hypothermia did not protect the hippocampus following neonatal hypoxic ischemia in a murine model.30 Nissl bodies were used as a marker of neuronal functional state in this study. The results showed that neuronal function was severely impaired in mice with CP, but it could be recovered using hUC-MSC-exos, and a better effect was observed with ip. injection of hUC-MSC-exos combined with mNGF. This method may be used in the future to alleviate symptoms caused by hippocampal damage.

Neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) causes permanent motor deficit (CP) and may result in significant disability and death. The brain damage process, the “HIE cascade,” is divided into 6 stages35: 1) energy depletion, 2) impairment of microglia, 3) inflammation, 4) excitotoxicity, 5) oxidative stress, and 6) apoptosis in capillaries, glia, synapses, and/or neurons. Synapses are functional connections between neurons and key parts of information transmission.36 In line with a previous study,35 the results of this study indicate that the ultrastructure was blurred and the synaptic structure was obviously damaged in mice with CP. However, a combination of hUC-MSC-exos and mNGF treatment could promote the recovery of synaptic function and improve nerve conduction function to improve motor function in mice.

Synaptophysin and PSD-95 mainly regulate synaptic formation and synaptic plasticity. Synaptophysin is a synaptic vesicle glycoprotein that is expressed in neuroendocrine cells and in most neurons in the CNS.37 It is a hallmark of synaptic vesicle maturation, and it is also considered an indirect marker of synaptogenesis in the developing brain.38 Likewise, PSD-95 is involved in the maturation of excitatory synapses.39 Evidence has shown that PSD-95 is a promising target for ischemic stroke therapy, as well as for other CNS disorders, as it protected synapses from β-amyloid,40 which were downregulated in an ischemia model.41 A recent study showed that the levels of presynaptic SYN and postsynaptic PSD-95 decreased in the hippocampus of LPS-exposed mice, which might contribute to the impairment of synaptic plasticity and the decline in learning and memory observed in behavioral tests, suggesting that impairments in synaptic plasticity might be responsible for LPS-induced cognitive deficits.42 Interestingly, this study also found that SYN and PSD-95 proteins were downregulated in the hippocampus of mice with CP, suggesting synaptic formation and dysfunction of neurotransmitters in mice with CP. This phenomenon supports the results of the TEM in this study. However, after mice with CP were injected with hUC-MSC-exos and mNGF, the levels of synapse-associated proteins SYN and postsynaptic PSD-95 both increased significantly, suggesting that hUC-MSCs-exos combined with mNGF could promote the reconstruction of contact structures and improve synaptic conduction and neural information transmission. Therefore, the modulation of these proteins by hUC-MSCs-exos or mNGF could lead to the long-term modulation of synaptic transmission, affecting motor control.

This study demonstrated the considerable efficacy of combining human umbilical cord MSC (hUC-MSC)-derived exosomes with mNGF in alleviating motor disorders and brain pathological injuries in mice with CP. These treatments may promote neuroregeneration and repair, enhancing synaptic stability and function, thereby improving neurological impairments in CP. Additionally, they could reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, protecting neurons from further damage and facilitating brain injury repair. These findings lay a critical theoretical foundation for developing innovative therapeutic strategies for CP. The successful outcomes of combined exosome and nerve growth factor therapy underscore the potential of stem cell-derived biologics to enhance neurological function in CP. This combination could significantly enhance therapeutic efficacy, potentially establishing a pivotal approach for future CP treatments. Moreover, this study provides essential theoretical support for the clinical application of this combined therapy. Further clinical studies are necessary to validate the safety and efficacy of this therapy, potentially offering new treatment options for patients with CP. Additional research should also determine the optimal dosages, administration routes and timing for this therapy to customize treatment strategies and maximize therapeutic benefits.

Limitations

Immunohistochemical analysis could not be conducted in this study due to financial constraints; however, it will be addressed in future research. Definitive evidence confirming the role and mechanism of action of hUC-MSC-exos combined with mNGF in CP models is still lacking. Detailed mechanisms of action still need to be clarified.

Conclusions

Combined therapy using exosomes derived from hUC-MSCs and mNGF shows promising mechanisms and translational implications, which is relevant to clinical practice in managing motor disorders and brain injuries in CP.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14212279. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. The research design.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.