Abstract

Background. The variability and disparities in the recommended targets across different international guidelines suggest the optimal oxygen saturation (SpO2) target for acute respiratory failure (ARF) patients be further explored.

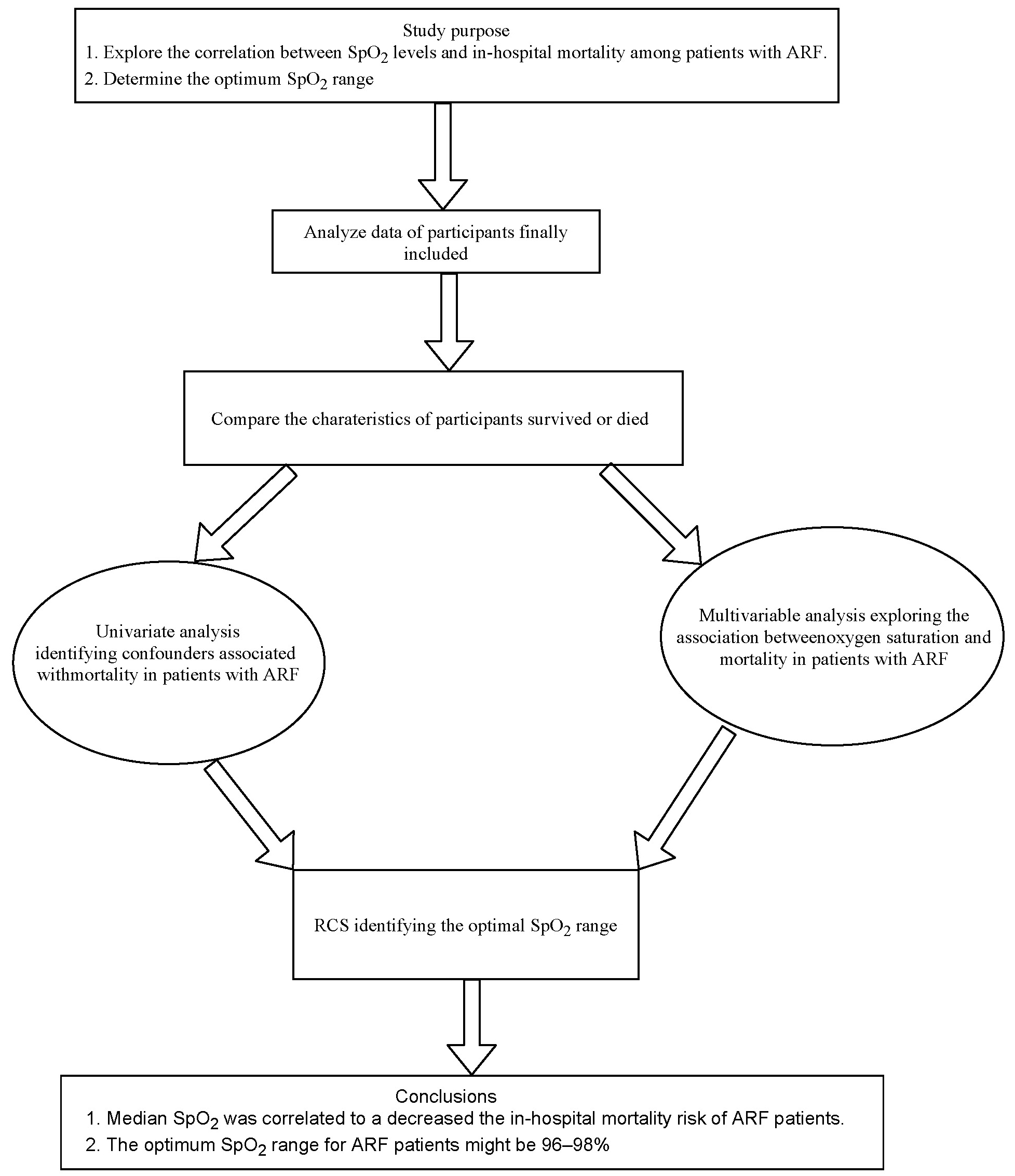

Objectives. To explore the association between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, as well as to determine the optimum SpO2 for ARF patients.

Materials and methods. In this cohort study, 3,225 ARF patients were included at the end of the follow-up; among them, and 1,249 patients survived and 1,976 died. The restricted cubic spline (RCS) was drawn to show the nonlinear association between the median SpO2 and the risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients and to identify the optimal range of SpO2. Cox regression was applied to identify the association between the median SpO2 and the risk of in-hospital mortality in ARF patients. Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted to identify the in-hospital mortality of ARF patients.

Results. The in-hospital mortality rate was 61.2% in all ARF patients at the end of the follow-up. The median SpO2 was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients after adjusting for confounders (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.95, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.93–0.97). The median SpO2 was non-linearly correlated with the in-hospital mortality of ARF patients. The overall survival (OS) was higher in the 96–98% group. A median SpO2 ≤ 96% was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality in ARF patients accompanied by malignant cancer (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.24–1.94), renal failure (HR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24–1.70), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; HR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.27–2.28) and atrial fibrillation (AF; HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.02–1.53). The median SpO2 > 98% was associated with an elevated risk of in-hospital mortality in ARF patients accompanied by AF (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.04–1.44).

Conclusions. The median SpO2 was linked to a decreased risk of in-hospital mortality in ARF patients.

Key words: in-hospital mortality, acute respiratory failure, oxygen saturation, non-linear correlation

Background

As a common disease in critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs), acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a heavy healthcare burden.1 The reasons causing ARF are usually acute pathogenic factors, including severe shock, electric shock, trauma, lung diseases, and acute airway obstruction, resulting in a precipitous deterioration of pulmonary function.2, 3 Acute respiratory failure was reported to result in about 2.5 million ICU admissions4, 5 and causing a mortality rate of over 30% every year.6 In patients with ARF, the body’s compensation does not occur within the short timeframe in which rescue needs to be performed.7 Mechanical ventilation (MV) is one of the most vital life-supporting interventions for ARF patients.8 Supplemental oxygen is important for ARF patients receiving MV in ICUs.9 When oxygen is provided to patients in ICUs requiring MV, the absence of appropriate oxygen management might lead to potential iatrogenic harm to patients.10 Improving the oxygen management for ARF patients requiring MV is essential.

The maintenance of arterial oxygen saturation, evaluated using oxygen saturation (SpO2), is crucial in clinical care. The need for oxygen supplementation in patients is dependent upon peripheral SpO2 thresholds. Setting SpO2 targets towards the higher end of the range provides a safety margin against hypoxemia but may increase the risk of hyperoxemia and tissue hyperoxia, leading to oxidative damage and inflammation.11, 12 Evidence published in 2018 and 2019 suggested that ARF patients receiving MV with high fractions of inspired oxygen were associated with excess morbidity and mortality.13, 14 Also, patients with ARF experienced hypoxic damage when the delivery of oxygen to tissues failed to meet their oxygenation demands, potentially resulting in organ failure and mortality.15 The study conducted by Siemieniuk et al. in 2018 demonstrated that a SpO2 > 96% might increase the mortality of patients compared to a SpO2 < 96%.16 Another study by Barrot et al. in 2020 revealed that conservative oxygen therapy was harmful for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients.17 Some recent guidelines recommend a SpO2 < 96% in patients receiving MV; however, the acceptable lower limit was unclear.16, 18 The variability in current clinical practice19 and disparities in the recommended targets across different international guidelines16, 18 suggested the need for further exploration of the optimal SpO2 target for ARF patients.

Objectives

This study aimed to explore the correlation between SpO2 levels and in-hospital mortality among patients with ARF. The optimum SpO2 range was also determined. Subgroup analysis explored the association between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality among patients with ARF in patients with different types of complications.

Material and methods

Study design and population

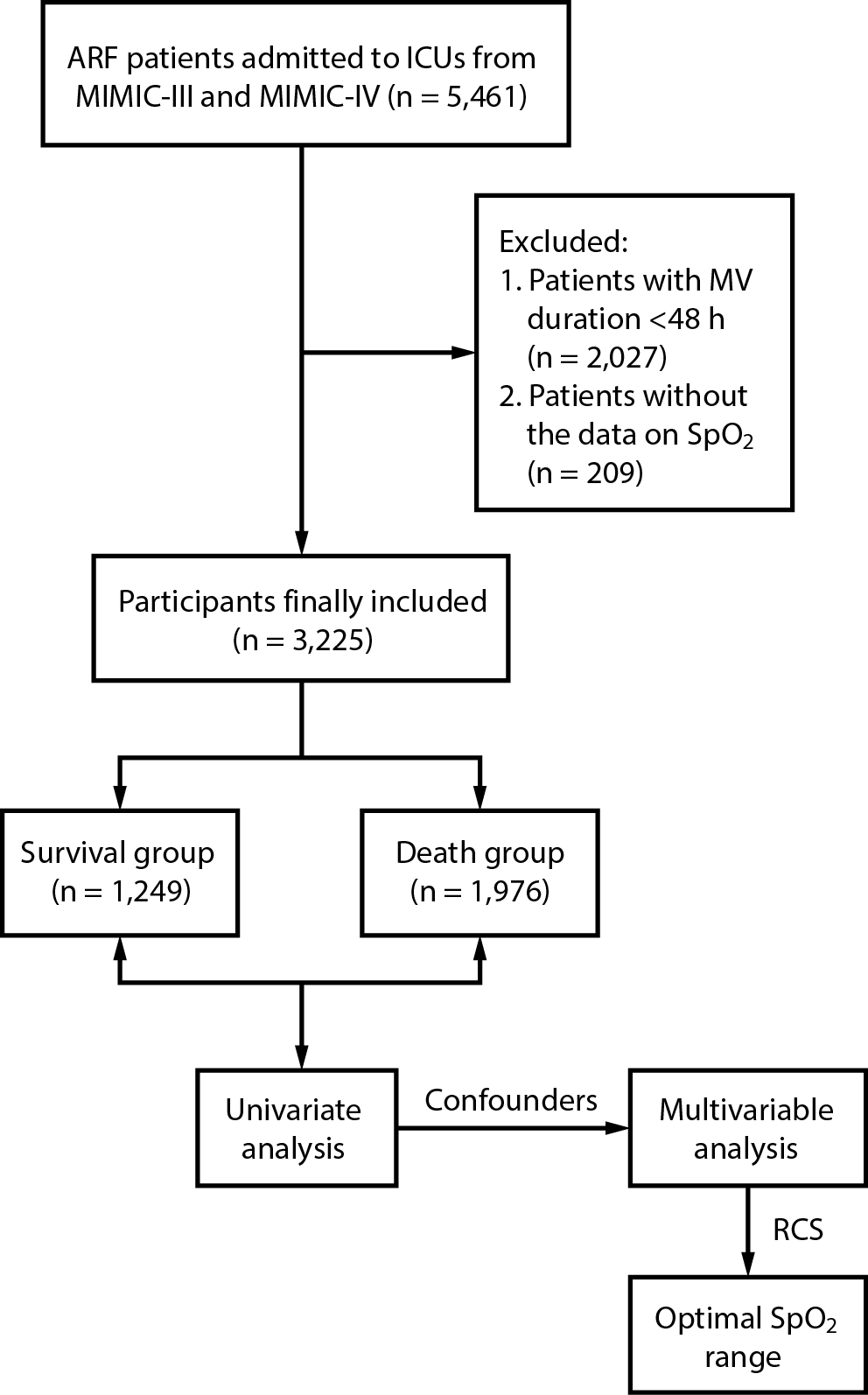

This was a cohort study involving 5,461 ARF patients admitted to ICUs from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-III (MIMIC)-III (v. 1.4) and MIMIC-IV (v. 1.0). Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care is a free critical care database from a single center, containing data on 46,520 patients admitted to the ICU of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC; Boston, USA) between 2001 and 2012.20 This study encompassed demographics, fluid balance, laboratory tests, and vital status and signs. International Classification of Diseases and 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes, hourly physiologic data from bedside monitors validated by nurses in the ICU, and written estimates of radiologic films from specialists covering respective time periods for each patient were recorded.21 Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV is an updated version of MIMIC-III, including data of patients from 2008 to 2019.22 In our study, patients with a MV duration <48 h and those without data on SpO2 were excluded, and finally, the data of 3,225 patients were followed up. After the conclusion of the follow-up period, 1,249 patients survived, while 1,976 patients succumbed to their illnesses. The project received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, USA). The requirement for individual patient consent was waived due to the project’s lack of impact on clinical care and the de-identification of all protected health information.

Data collection

The collected data included, age (years), heart rate (breaths/min), diastolic blood pressure (DBP, mm Hg), systolic blood pressure (SBP, mm Hg), mean arterial pressure (MAP, mm Hg), history of diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), atrial fibrillation (AF), lung cancer, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, renal failure, malignant cancer, and respiratory-related parameters including fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), SpO2 (%), partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2, mm Hg), Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPSII), MV duration, and MV fraction. All data were collected using the first measurements during ICU admission.

Outcome variables

The outcome was assessed by evaluating in-hospital mortality among ARF patients. The follow-up was started 48 h after ICU admission with an endpoint of follow-up when the patients died in the hospital or were discharged. The median duration of follow-up was 15 (10–23) days.

Statistical analyses

The Levene’s test was used to test the homogeneity of variance. The results of the Levene’s test of variables are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The central limit theorem (CLT) assumes that the distribution of variables differs statistically insignificantly from the normal distribution, and measurement data were described as mean and standard deviation (mean (±SD)). A t-test was used for comparison among groups with homogeneous variances, and a t-test was used for heterogeneity of variance. The enumeration data were described in terms of numbers and percentages of cases (n (%)). If the assumption of expected abundance (n < 5 ≤ 20% of cells) for the χ2 test was achieved, Pearson’s nonparametric χ2 test of independence without Yates’s continuity was used. A univariable Cox proportional hazards model was established to identify potential confounding factors. The Cox proportional hazards assumption was tested. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, there was no linear relationship between covariates and logarithmic hazards. Likelihood ratio (LR) test and Wald’s test were used to judge whether the fitting of the model was significant. The former uses the logarithmic likelihood values of the 2 models to test the difference. The latter is a hypothesis that tests whether the value of a set of parameters is equal to 0. If the variable remained significant under both tests, it was regarded as a statistical difference and adjusted as covariates in the multivariable proportional Cox hazards model. The assumption of collinearity among predictors was tested for proportional Cox hazard regression. The non-collinearity of predictors assumption was evaluated with a multicollinearity, variance inflation factor (VIF) <10, which was then regarded as no multicollinearity among the variables. Whether the standardized Schoenfeld residuals were related to time was used to assess whether the model met the proportional hazards assumption. If a p > 0.05 in both the single variable and global variable was found, it was considered that the Schoenfeld residuals were independent of time. More detailed information on Schoenfeld residues is shown in Supplementary Table 2. A standardized Schoenfeld residual relative to time correlation of each covariate is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Comprised of the magnitude of the maximum dfbeta value with the regression coefficients, all observations are not very different from those in each row and are uniformly distributed on both sides of the y = 0 reference line, with relative symmetry. The restricted cubic spline (RCS) was drawn to show the nonlinear association between median SpO2 and the risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients and identify the optimal range of SpO2 using ggplot2, rms, ggthemes, ggsci, and cowplot packages in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The function name and basic code are shown in the Supplementary File 1. To further illustrate the different median SpO2 groups with the risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, a subgroup analysis was performed. R was applied for data analysis with a p < 0.05 set as statistical difference.

Results

The baseline data of the participants

In total, 5,461 ARF patients were involved in this study. Among them, patients with a MV duration <48 h (n = 2,027) and patients without the data on SpO2 (n = 209) were excluded. Finally, 3,225 patients were included. The screening process is shown in Figure 1. At the end of follow-up, those who survived were classified into the survival group (n = 1,249), and those who died were allocated into the death group (n = 1,976).

As for the characteristics of participants in the survival and death groups, the mean SBP (125.7 mm Hg vs 123.2 mm Hg), DBP (67.9 mm Hg vs 64.2 mm Hg), MAP (89.3 mm Hg vs 81.3 mm Hg), FiO2 (50.0% vs 1.0%), and SpO2 (97.6% vs 97.4%) were higher in the survival group. The percentages of ARF patients complicated with COPD (17.6% vs 10.3%), lung cancer (3.4% vs 1.0%), liver cirrhosis (12.5% vs 6.4%), congestive heart failure (44.2% vs 29.2%), heart disease (12.9% vs 9.7%), renal failure (55.9% vs 44.0%), and malignant cancer (26.7% vs 12.3%) was higher in the death group compared to the survival group. The detailed characteristics of patients in the survival and death groups are presented in Table 1.

Potential confounding factors associated with in-hospital mortality of ARF patients

To identify the association between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify potential confounding factors associated with the in-hospital mortality of ARF patients. According to the data in Table 2, age (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.02, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.02–1.02), SBP (HR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00), DBP (HR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00), MAP (HR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00), FiO2 (HR = 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.00), complicated with COPD (HR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.07–1.35), lung cancer (HR = 2.53, 95% CI: 1.98–3.23), AF (HR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.08–1.29), liver cirrhosis (HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.22–1.59), congestive heart failure (HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15–1.37), hyperlipidemia (HR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99), and malignant cancer (HR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.40–1.71), and a SOFA score (HR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03) were potential confounders associated with the in-hospital mortality of ARF patients. The results of the non-collinearity of the predictors’ assumptions showed there was no multicollinearity among the variables (VIF < 10, Table 3) and all the variables were not related to time (Figure 2).

The association between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of acute respiratory failure (ARF)patients

In the unadjusted model, the median SpO2 level might be related to a decreased in-hospital mortality risk of ARF patients (HR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.99). Multivariable Cox regression depicted that the median SpO2 was related to a decrease in the in-hospital mortality risk of ARF patients (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93–0.97) after adjusting for confounders including DBP, SBP, age, FiO2, lung cancer, liver cirrhosis, AF, hyperlipidemia, malignant cancer, and SOFA score (Table 4).

The non-linear association between median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients

Furthermore, we wanted to identify the optimum SpO2 range for ARF patients. The data of RCS delineated that there was a nonlinear correlation between the median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients (Figure 3). There were 2 nodes of median SpO2 in this RSC, which were at 96.8% and 98.3%. When the median SpO2 was between 96% and 98%, the HR for in-hospital mortality of ARF patients was <1, suggesting the risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients was decreased. The survival curves showed that overall survival (OS) was higher in the median SpO2 between 96% and 98% group than both the SpO2 ≤ 96% group and SpO2 > 98% group (Figure 4).

The correlation between median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients with different complications

Subgroup analysis was conducted in ARF patients with different comorbidities. The median SpO2 level was correlated with a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality among patients diagnosed with malignant cancer (HR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.96), renal failure (HR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.90–0.96), lung cancer (HR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.74–0.99), and COPD (HR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97) after adjusting for age, SBP, DBP, FiO2, lung cancer, liver cirrhosis, AF, hyperlipidemia, malignant cancer, and SOFA score (Table 5). In addition, we observed that ARF patients with malignant cancer (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.24–1.94), renal failure (HR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24–1.70), COPD (HR =1.70, 95% CI: 1.27–2.28) or AF (HR =1.25, 95% CI: 1.02–1.53) who had a median SpO2 ≤ 96% were at an increased in-hospital mortality risk. The presence of a median SpO2 > 98% was related to an elevated risk of in-hospital mortality among ARF patients with AF (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.04–1.44, Table 6).

Discussion

In the current study, the relationship between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, as well as the optimum SpO2 target for ARF patients, was explored. The results indicated that the median SpO2 correlated with a decrease in the in-hospital mortality risk of ARF patients, and there was a nonlinear association between median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients. The optimum SpO2 range for ARF patients may be 96–98%. Subgroup analysis depicted that a median SpO2 ≤ 96% was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality among ARF patients with malignant cancer, renal failure or COPD. In ARF patients accompanied by AF, both a median SpO2 ≤ 96% and a median SPO2 > 98% were correlated with an elevated in-hospital mortality risk. These findings might offer insight for clinicians in choosing the optimum SpO2 in ARF patients and help improve the prognosis in ARF patients.

In our study, we found that there was a nonlinear correlation between median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality. A former study similarly demonstrated a U-shaped correlation between time-weighted partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) values and death of mechanically ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients, with both lower and higher levels of PaO2 being linked to an increased mortality risk.23 In several previous studies, the SpO2 target for improving outcomes of ICU patients was explored. Girardis et al. found that conservative oxygen therapy with a SpO2 between 94% and 98% correlated with reduced ICU mortality compared to conventional oxygen therapy between 97% and 100% in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU for ≥72 h.24 Another study revealed that the 28-day mortality in the conservative-oxygen group using a SpO2 from 88% to 92% was 34.3%, and in the liberal-oxygen group with a SpO2 ≥ 96% was 6.5% in ARDS patients.17 Asfar et al. delineated that hyperoxia was correlated to increased weakness, atelectasis and mortality in patients.25 Another study based on the eICU Collaborative Research Database and the MIMIC Database indicated that the optimal range of SpO2 in critically ill patients was 94–98%.26, 27 The British Thoracic Society recommended a SpO2 target of 94–98% for most acutely ill patients. These findings implied that the SpO2 target should be <98%.

Herein, the optimal target of SpO2 for ARF patients might be 96–98%. The in-hospital mortality risk of ARF patients was decreased in those with SpO2 between the 96% and 98%. This was because a SpO2 ≤ 96% might cause hypoxemia. Hypoxemia might lead to damage to multiple organs causing a lack of oxygen to the brain, which can cause drowsiness or coma or affect the blood supply to the myocardium, resulting in myocardial injury.28 On the other hand, a SpO2 > 98% might lead to hyperoxemia in ARF patients. Several studies uncovered that hyperoxemia may be associated with a variety of sequelae in patients receiving MV through lung tissue damage or reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation.29 Hyperoxia might also affect the innate immune system, such as attenuating cytokine production by human leukocytes, inducing structural changes within alveolar macrophages, and increasing in production of serum interleukin (IL)-10, IL-6 and ROS.30 For patients with ARF, clinicians should be careful with the SpO2 level, and the target SpO2 should be controlled at 96–98%.

Herein, subgroup analysis found that for ARF patients with malignant cancer, renal failure, lung cancer, or COPD, the accepted lower limit of SpO2 might be 96%. Some clinicians suggested adjusting the oxygenation target based on the severity of pulmonary disease.31 In ARF patients with lung cancer or COPD, ARF may be a result of the disease itself, complications in treatment or comorbidities.32 The co-occurrence of these diseases might increase mortality by 20% relative to those without comorbidities.33 In ARF patients complicated with other diseases, lung diseases may be more serious, and a higher target for SpO2 might be required. Previously, Adda et al. found that the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was lower (175 vs 248) in ARF patients with hematologic malignancies who failed noninvasive ventilation and required endotracheal intubation compared with those not requiring MV,34 indicating that ARF patients with malignancies, a sufficient SpO2 is needed.

This study identified a nonlinear association between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, indicating the importance of selecting an optimal SpO2 target for ARF patients. Further, the optimum SpO2 target for ARF patients was identified. The levels of SpO2 were non-normally distributed, which could better reflect the status of patients at the beginning and end of treatments than the mean value. Some previous studies explored PaO2 rather than SpO2 to determine the status of oxygenation.10, 35 Arterial blood oxygen pressure cannot be measured continuously, and frequently arterial blood draws for blood gas analysis are required for measuring it.36 The acquisition of PaO2 is invasive, requiring special equipment, which cannot be used for real-time monitoring. On the other hand, oxygen saturation, measured with pulse oximetry, is simple and noninvasive and can be used for the real-time monitoring of patients.17 Oxygen saturation can be continuously monitored, enabling earlier detection of potential ARDS patients, which is of great significance as early interventions can improve the outcomes of patients. We also analyzed the SpO2 target in patients complicated with different diseases, which might provide specific suggestions to those with different underlying diseases. These findings might offer a guide for informing future trials of oxygen therapy to help clinicians in the management of MV in ARF patients. Future clinicians may also place a greater emphasis on the continuous monitoring of SpO2 and titration of oxygen supplementation for ARF patients in the ICU, exercising caution when conducting detailed evaluations of adherence to oxygen targets, exposure to supplemental oxygen, and the incidence and duration of hypoxemia in patients with ARF.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, the detailed information on MV treatment was not analyzed. Second, the data of SpO2 was measured once an hour, and the measurement of SpO2 could be more frequent and flexible depending on the clinical practice. Third, all the data were identified in the MIMIC database, resulting in some recall bias. The findings in this study still require validation in future studies.

Conclusions

The relationship between SpO2 and in-hospital mortality in ARF patients and the optimal SpO2 range for ARF patients were investigated. The results identified that the median SpO2 was linked to a decreased risk of in-hospital mortality of ARF patients, and there was a nonlinear correlation between median SpO2 and in-hospital mortality of ARF patients. For ARF patients, continuous monitoring of SpO2 is necessary, and the optimal SpO2 range might be 96–98%.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary files are available at https://doi.org/

10.5281/zenodo.11463445. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1 The results of the Levene’s test of variables.

Supplementary Table 2 The information of Schoenfeld residues of variables.

Supplementary Fig. 1. The RSC shows a nonlinear relationship between covariates and logarithmic hazards.

Supplementary Fig. 2. A standardized Schoenfeld residual relative to the time correlation of each covariate.

Supplementary File 1. The function name and basic code of statistical analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)