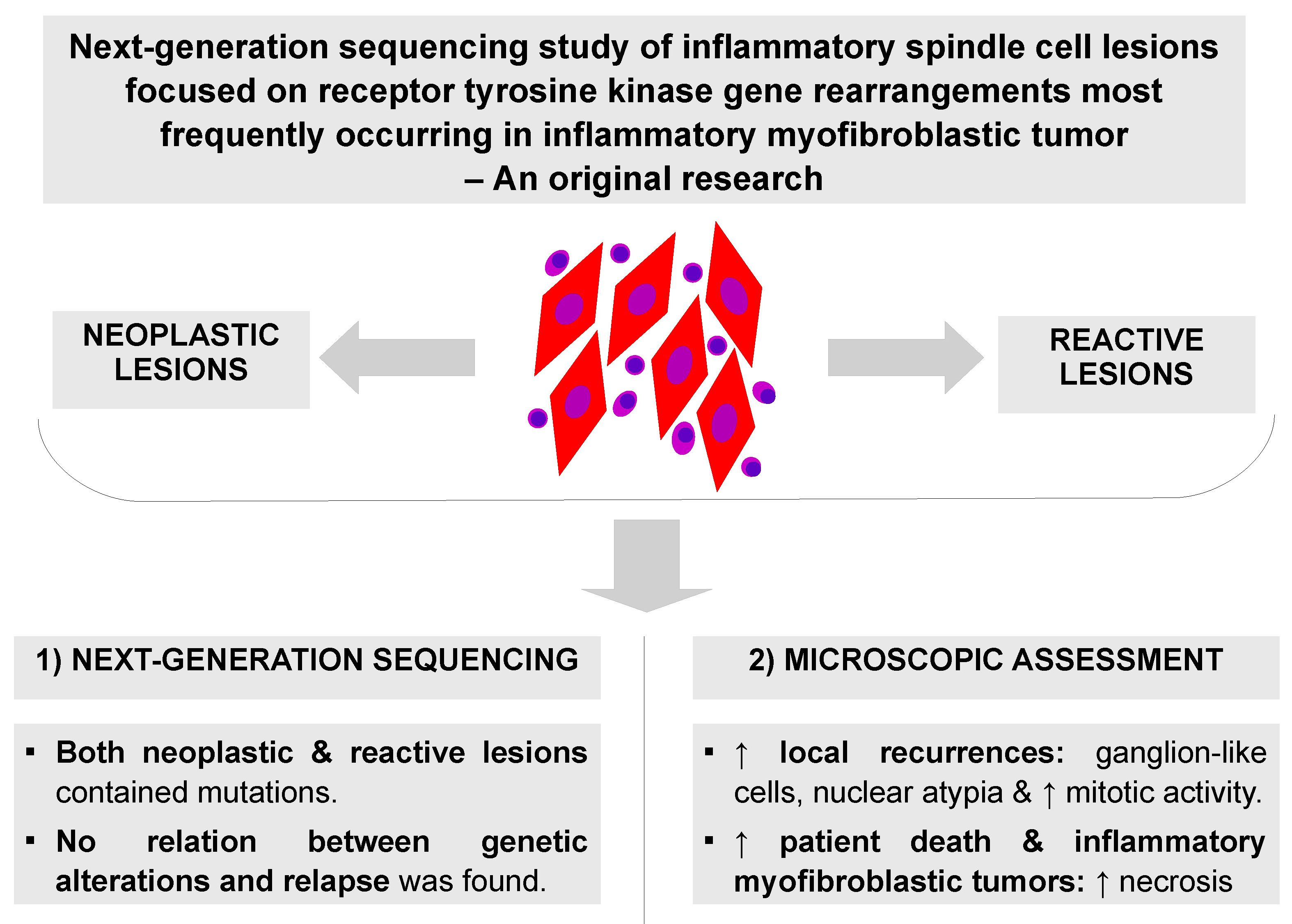

Abstract

Background. A group of inflammatory spindle cell lesions (ISCLs) includes many nosological entities with a common histological image consisting of spindle-shaped cells and inflammatory infiltrate. Diverse diseases indicate different prognoses that can be difficult to predict. The most well-known neoplasm from the group is an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) that harbors tyrosine kinase gene rearrangement frequently affecting ALK, ROS1, RET, PDGFRB, NTRK, and IGF1R genes. In contrast, a reactive mass-forming lesion is regarded as an inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT).

Objectives. This study aimed to: 1) investigate the accuracy of the primary diagnosis of IMT and IPT with the diagnostics using extended analysis of clinical data, re-evaluation of histopathological slides and next-generation sequencing (NGS); and 2) to establish prognostic and diagnostic factors.

Materials and methods. Finally, 46 cases of ISCLs were retrieved. The authors revised diagnoses and performed NGS based on ribonucleic acids isolated from selected paraffin blocks. Clinical and paraclinical data were also collected. The final diagnoses were made as a result of available information integration.

Results. The sequencing confirmed 4 IMTs and detected 4 fusion gene types – EML4-ALK, RANBP2-ALK, and ETV6-NTRK3. Additionally, 1 afunctional EGFR-PPARGC1A rearrangement was found in gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp. A subset of reactive lesions also contained some mutations, which is consistent with actual knowledge. Neoplasms with ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity gave local recurrences. A higher percentage of necrosis indicated IMTs and patients who died in the analyzed period. No relation between genetic alterations and relapse was found.

Conclusions. A final diagnosis can be made based on all clinical and paraclinical data. The prognosis after the treatment is dependent on the pathological diagnosis, disease location and resection completeness, presence of ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia, mitotic index, and necrosis. Not only neoplastic but also reactive lesions can recur. The presence of gene rearrangements and necrosis can have diagnostic value.

Key words: next-generation sequencing, receptor tyrosine kinase, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, inflammatory pseudotumors, inflammatory spindle cell lesions

Background

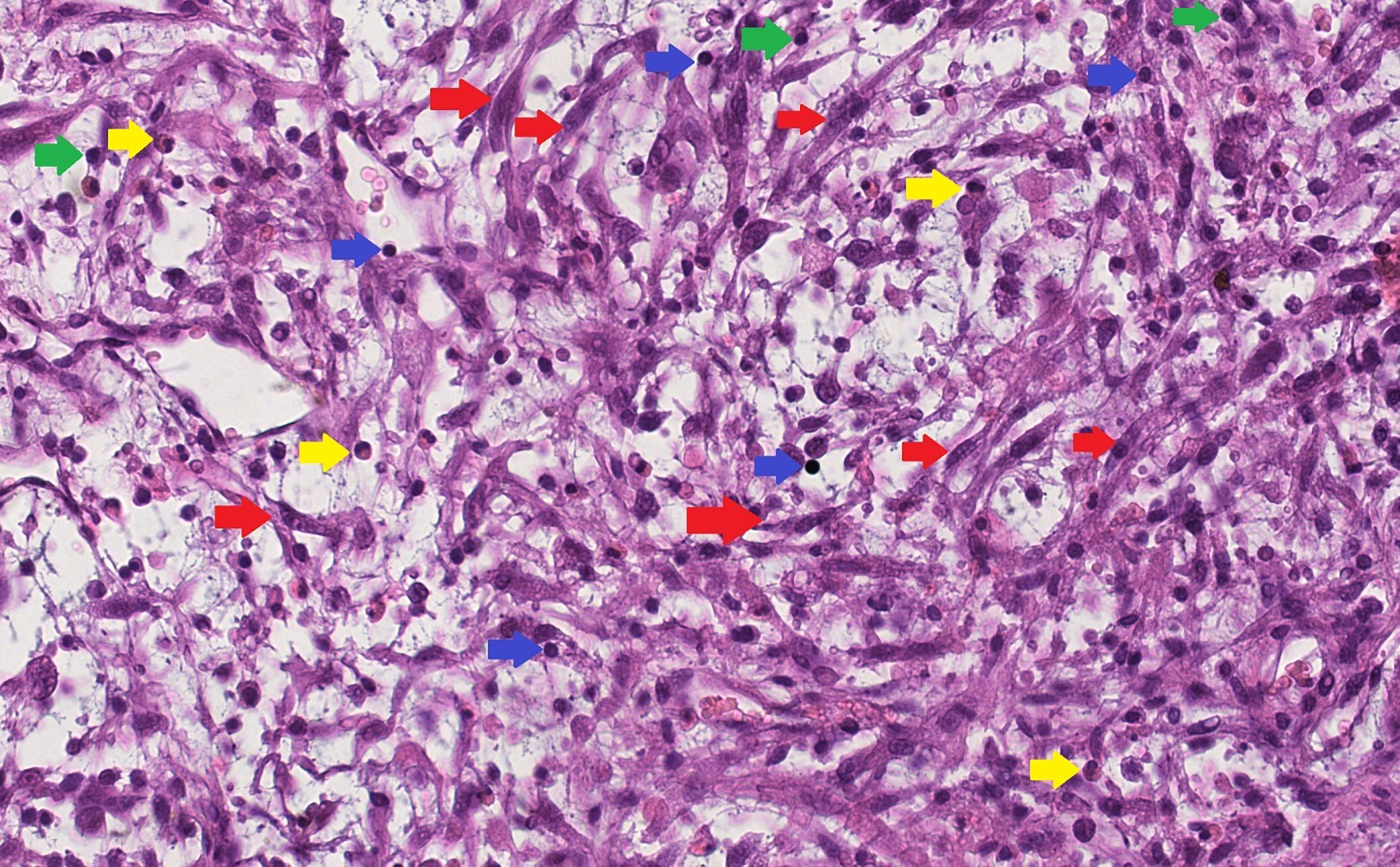

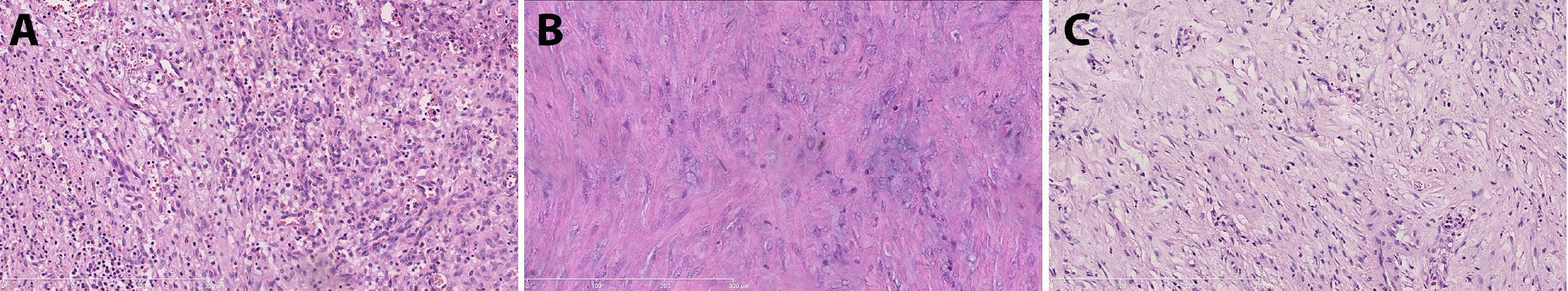

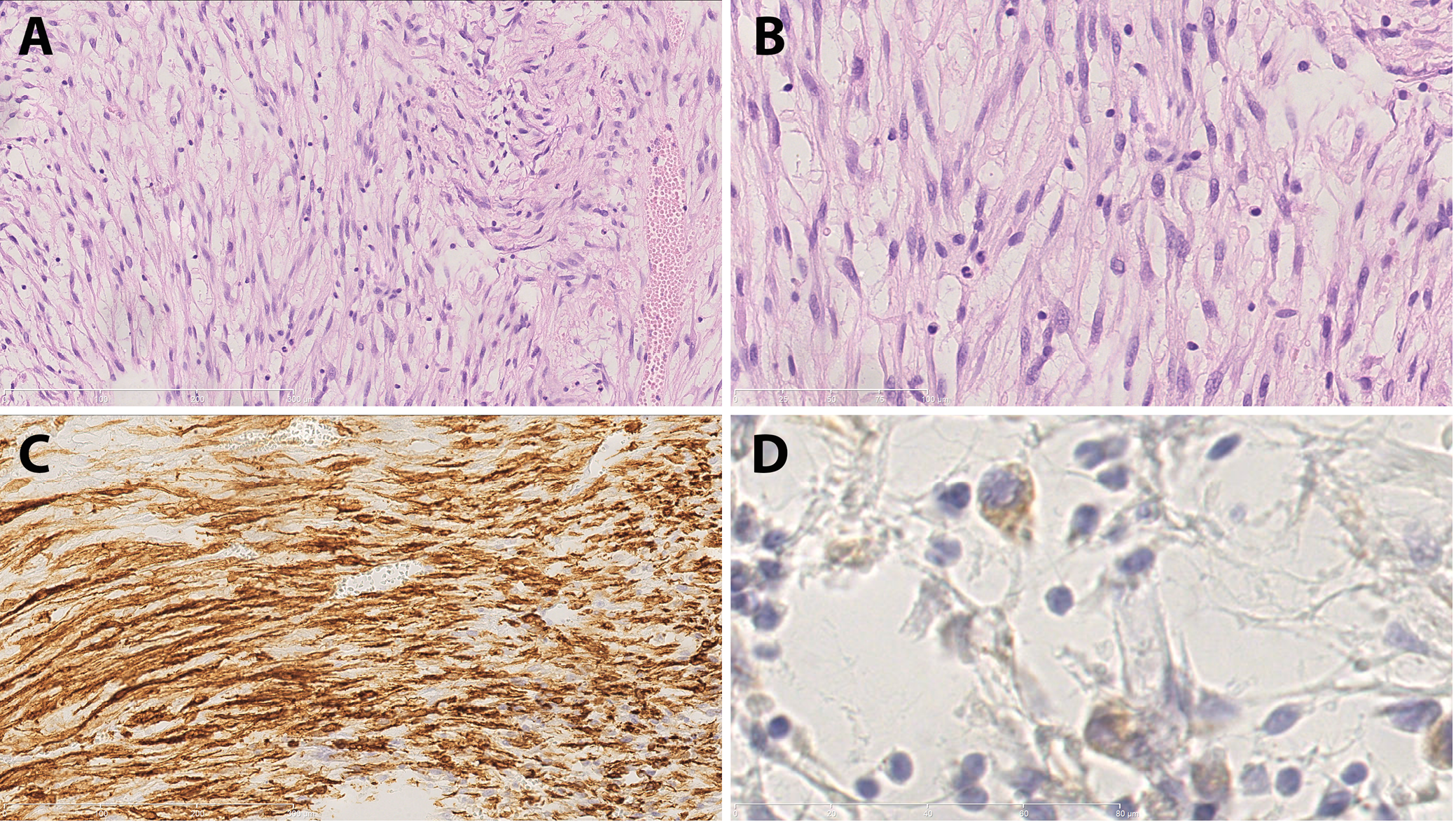

Inflammatory spindle cell lesions (ISCLs) represent a histologically defined group of disorders. Microscopically, they are characterized by the presence of spindle-shaped cells interspersed with a dense inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). This group is heterogeneous in nature, encompassing a range of distinct pathological entities.1, 2, 3, 4 Initially, ISCLs were divided into 2 subgroups: 1) a neoplastic lesion – an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT); and 2) a reactive lesion – an inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT).1 Subsequently, the group was gradually expanded.3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Any secondary inflamed spindle cell neoplasm may be included in this group. However, establishing an accurate diagnosis can be challenging.19

Inflammatory spindle cell lesions may occur in any region of the human body, with symptoms and signs depending on the location.3 Radiological imaging is often heterogeneous and nonspecific.20 Correlation of histological features, molecular genetic testing, clinical history, and radiological data is essential for accurate diagnosis.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors are intermediate-grade neoplasms characterized by a relatively high recurrence rate and low metastatic potential. Under a light microscope, 3 major histopathological patterns can be distinguished: classical, hypocellular and hypercellular. A hypercellular pattern, high mitotic activity, presence of myxoid stroma, ganglion-like cells, multinucleated giant cells, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and infiltrative growth are considered adverse prognostic factors.3, 21 Approximately 50–60% of IMTs harbor ALK gene rearrangements. Other gene fusions – such as ROS1, PDGFRB, RET, NTRK1/3, and IGF1R – occur less frequently. Prior to the identification of these driver fusion genes, the terms IMT and IPT were sometimes used interchangeably by clinicians.3

Objectives

The aim of the study was to: 1) investigate the accuracy of primary diagnoses of IMT and IPT by incorporating extended clinical data analysis, re-evaluation of histopathological slides and next-generation sequencing (NGS); 2) determine whether pathological diagnoses, disease location, histological features, and genetic changes influence local recurrence of ISCLs.

Materials and methods

Participants

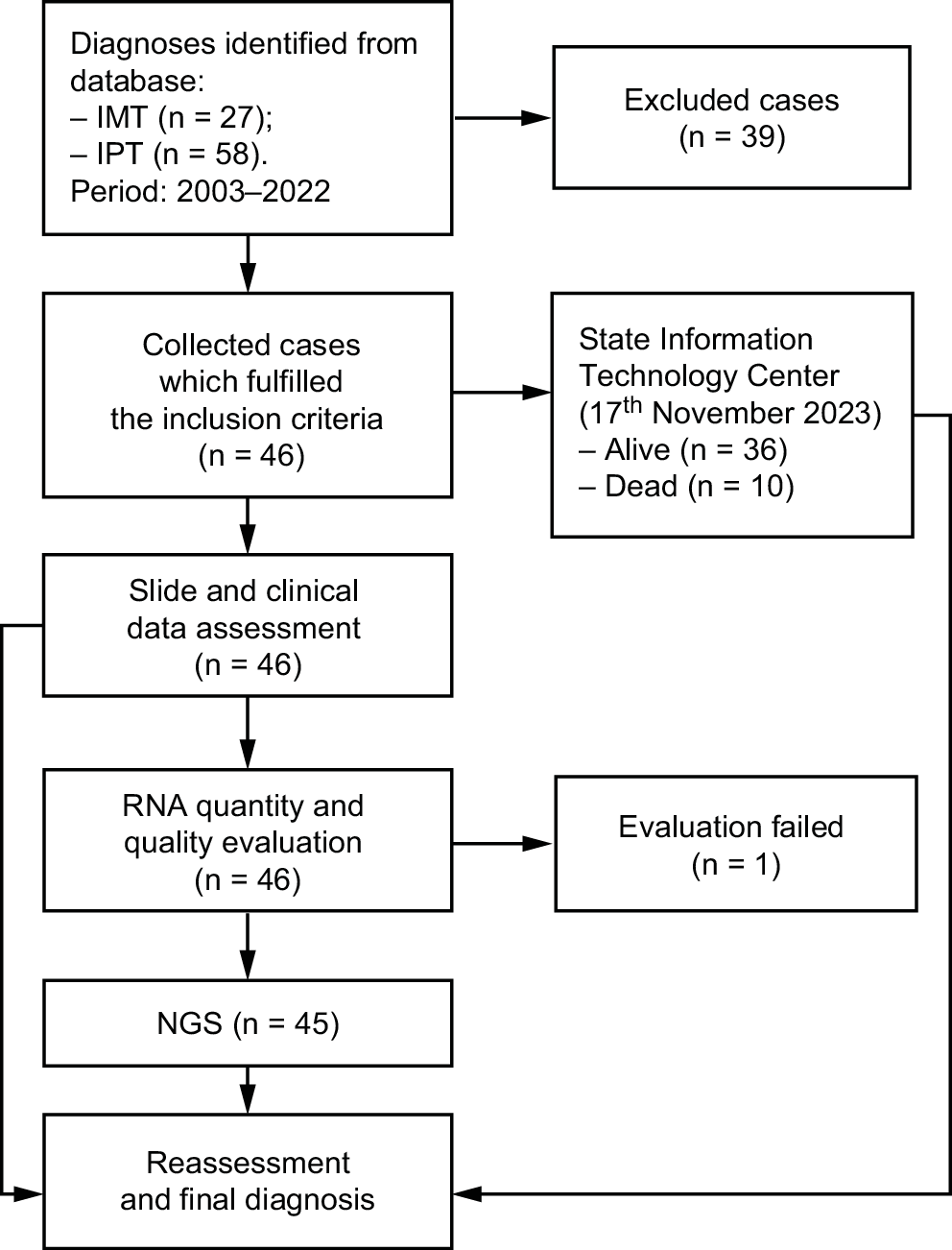

Eighty-five cases of ISCLs, initially diagnosed as IMT or IPT, were retrieved from the Department of Medical Pathomorphology, Medical University of Bialystok (Poland) database. After excluding 39 cases, 46 patients were included in the study (22 men and 24 women; most common lesion locations: abdomen and orbit). Based on the final histopathological diagnoses, the cases were classified into 2 groups: neoplastic (n = 24) and reactive (n = 22). Clinical and paraclinical data collected before and after diagnosis were analyzed for both groups.

Design and settings

The study was approved by Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice by the Bioethical Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok (approval No. APK.002.339.2020). First, archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were prepared using the Leica TP1020 tissue processor (Leica Camera AG, Wetzlar, Germany) and the HistoCore Arcadia H + C embedding system (Leica Camera AG) before the study. At this stage, standard reagents, including 10% buffered neutral formalin, xylene (isomeric mixture), ethanol, and paraffin wax, were used. Then, using the HistoCore AUTOCUT microtome (Leica Camera AG), 4–5 μm-thick sections were prepared and placed on SuperFrost Plus base glasses (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed using the ST5010 Autostainer XL (Leica Camera AG). Finally, histopathological slides were covered using CV5030 Glass Coverslipper (Leica Camera AG).

The initial evaluation of H&E-stained histopathological slides was performed by the 1st pathologist (K.S.) using a light microscope (Olympus BX43; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). A second opinion was provided for each case by the 2nd pathologist (J.R.G.). Final assessments were based on consensus between the 2 specialists. The histopathological evaluation included the following criteria:

− overall pattern (classical, hypocellular or hypercellular);

− degree of nuclear atypia, assessed according to the criteria proposed by Weir et al.22;

− percentage of necrosis;

− mitotic index, defined as the number of mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPF);

− intensity of the inflammatory infiltrate, graded according to the method presented by Klintrup et al.23;

− predominant type of inflammatory cells within the infiltrate;

− presence of ganglion-like cells, angioinvasion and perineural invasion.

Two pathology specialists reviewed all cases and selected 46 for the NGS procedure. Genomic RNA was extracted from the macrodissected FFPE material using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Quantity and quality of isolated RNA were determined using the NanoDrop 1000 UV Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Sample analysis was performed by NGS technology with the Archer® Fusion Plex® Lung Kit v. PI028.1 (ArcherDX, Inc, Boulder, USA) on the Illumina MiSeq platform. The NGS-based targeted sequencing assay allows detection of known and novel gene fusions, single nucleotide variations (SNVs), insertion/deletion polymorphism (indels), splicing, and gene expression. The kit contains 163 GSPs targeting 14 genes. The unique molecular on-target is above 93%. The assay targets are presented in Table 1. The recommended number of reads for all targets was 500,000. Data were analyzed using the Lung Target Region File and vendor-supplied software (Archer Analysis v. 6.2.7; Integrated DNA Technologies Inc.). The limit of detection (LoD) was defined as a minimum of 5 reads with at least 3 unique sequencing start sites spanning the breakpoint regions. The read length was paired-end, with a cut-off of 5% for variant allele frequency (VAF). The median coverage for all samples was 1,350.

Criteria

Following the analysis of clinical and paraclinical data, histopathological slide assessments and NGS results, the final diagnoses were established by 2 pathologists based on the World Health Organization (WHO) soft tissue tumor classification criteria24 (Figure 2). The inclusion criteria were: 1) primary histopathological diagnosis of IMT or IPT; 2) presence of FFPE blocks; 3) spindle cell morphology with inflammatory infiltrate resembling IMT; and 4) RNA integrity number (RIN) with a minimum value of 2. Cases were excluded if FFPE material was unavailable, if histopathological features differed from the study criteria, or if the RNA integrity number (RIN) was below 2.

Statistical analyses

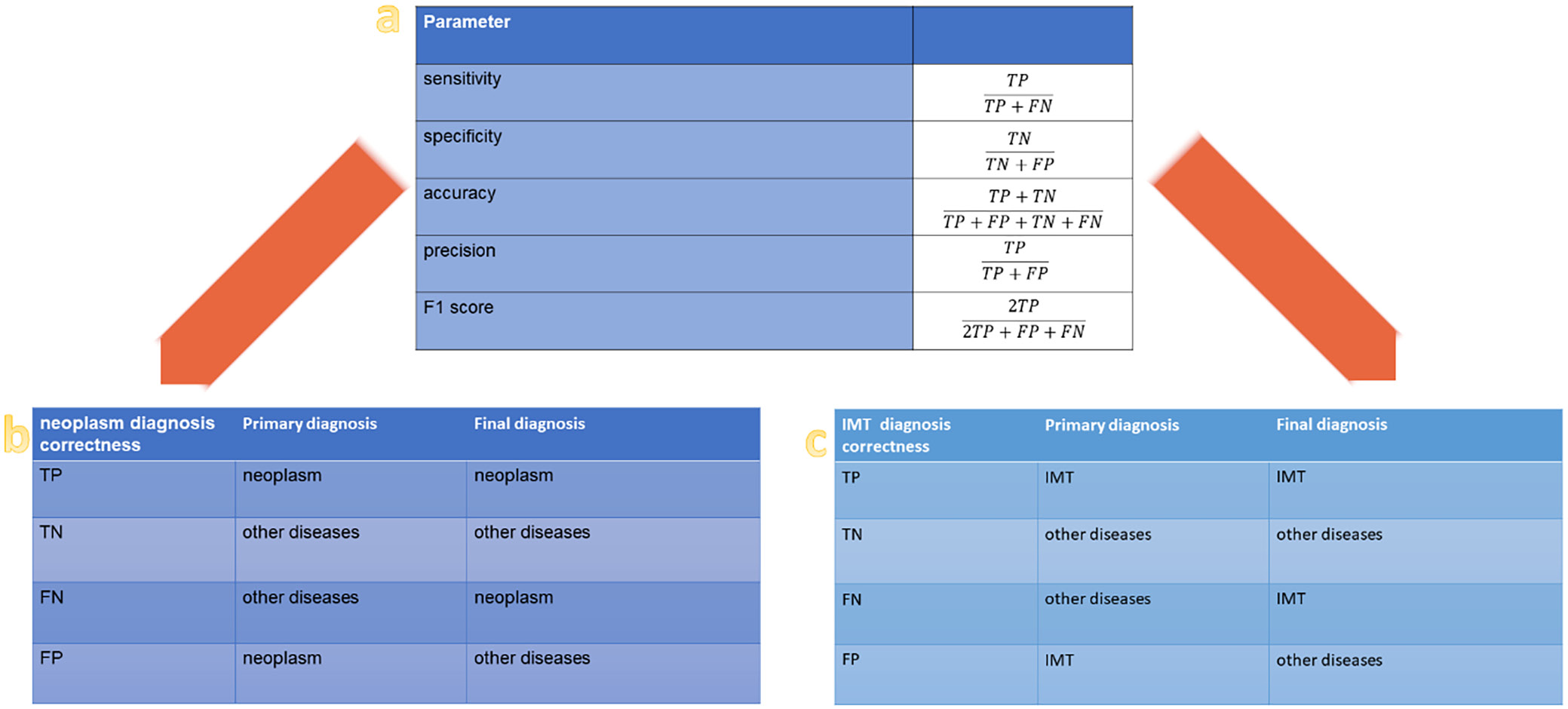

The statistical parameter formulas and definitions used for diagnostic verification are outlined in Figure 3. Dichotomous division was used at each stage of the analysis, e.g., neoplasms compared to other diseases, IMTs compared to other ISCLs, recurrent compared to non-recurrent cases, and patients who died compared to those who survived. To assess the impact of the dichotomous classification, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the 2 proportions were calculated using the method described by Tenny et al.25 These statistical parameters were selected because they effectively quantify the strength of association between the 2 groups (with and without events) in retrospective studies.25 Probability values (p-values) were calculated using the MedCalc online calculator (https://www.medcalc.org).

All numerical data (e.g., necrosis percentage, mitotic index) obtained through light microscopy represented subjective assessments by the pathologists. While these should be considered continuous variables, they could not be assumed to follow a normal distribution. The data obtained using NGS should be treated similarly. At each stage of the analysis, values were categorized into 1 of 2 groups; therefore, a nonparametric test was selected to account for the data distribution. A two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test was conducted at a 5% significance level using the Statistics Kingdom online calculator (https://www.statskingdom.com). Outlier values were included in the analysis.

Results

Histopathological assessment

The predominant tissue patterns were classical (41.3%), mixed (30.4%) and hypocellular (17.4%) (Figure 4). Nuclear atypia was observed in 17 cases (37%), mostly mild, while 3 cases (6.5%) contained ganglion-like cells. Necrosis was present in 26 cases (56.5%). Approximately ¾ of the lesions showed no mitoses. Chronic inflammatory infiltrates, primarily composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells, dominated among the cases. Angiovascular and perineural invasion were not observed.

The ORs for the presence of atypia and mitoses in neoplastic lesions compared to reactive lesions were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level: OR = 7.48 (95% CI: 1.74–32.17, p = 0.007) and OR = 7.14 (95% CI: 1.35–37.75, p = 0.021), respectively. These values were calculated using the method described by Tenny et al.25

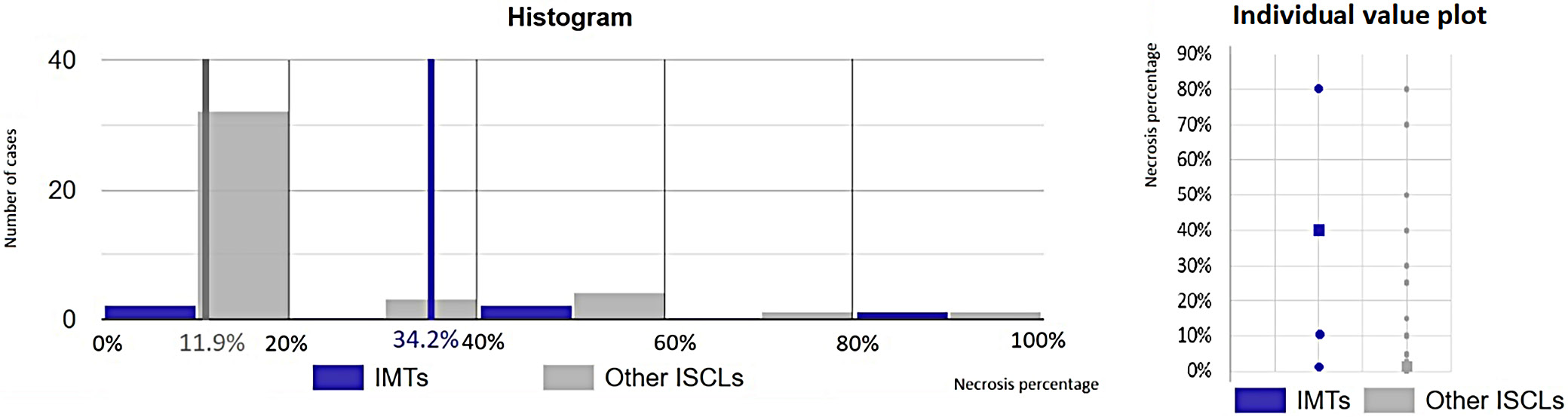

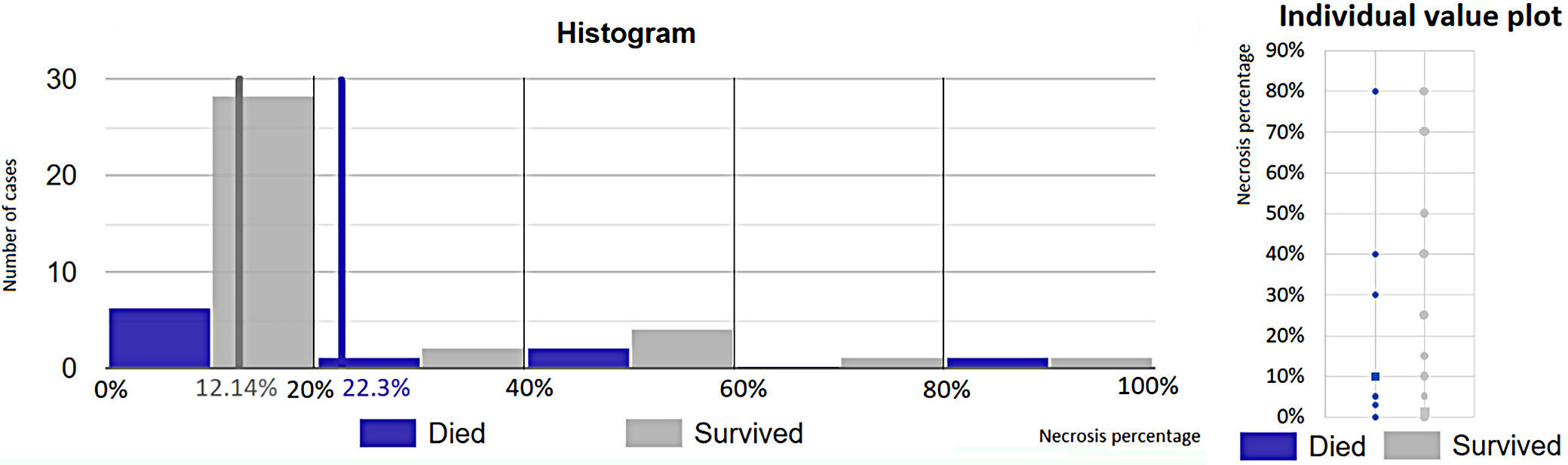

The estimated necrosis percentage in IMTs (cases 1, 2, 3, 4, and 46) compared to other ISCLs was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 162.5, p = 0.028). A statistically significant difference was observed, with the 1st group exhibiting a mean value of 34.2% compared to 11.9% in the 2nd group, at the 95% CI (Figure 5). Based on histopathological features and clinical data, 46 cases were qualified for molecular diagnostics.

Molecular diagnostics

Gene fusions

One sample (case 46) failed RNA quality and quantity control because the RIN value was below 2. Fusion genes were identified in 5 cases. Among them, 4 cases were ultimately diagnosed as IMTs due to the presence of tyrosine kinase rearrangements. Cases 1 and 2 presented an EML4-ALK fusion, while case 3 displayed a RANBP2-ALK fusion, which led to the diagnosis of epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma (EIMS) – a more aggressive variant of IMT. Case 4 was characterized by a translocation involving the NTRK3 and ETV6 genes. In case 5, an EGFR-PPARGC1A rearrangement, which was deemed nonfunctional due to the absence of a promoter, was identified in a gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp (Table 2).

Gene variants

Eighty-four genetic changes, including substitutions, insertions, duplications, and deletions, were identified across 58 gene variants through RNA NGS analysis. According to the Varsome database (https://varsome.com), these variants were classified as follows: 15 pathogenic, 17 likely pathogenic, 38 of uncertain significance, and 14 benign (Table 3). The most frequently observed pathogenic variants were nucleotide substitutions at positions 34 and 35 of the KRAS gene. These mutations were detected in multiple cases, including EIMS (case 3), Langerhans cell histiocytosis (case 11), inflammatory fibroid polyp (case 16), and IPTs (cases 21, 24 and 27).

Additionally, the most commonly identified likely pathogenic variant involved a cytosine-to-thymine substitution at position 2975 of the MET gene. The mutation was found in several cases, including orbital fibroma (case 8), inflammatory fibroid polyp (case 18), gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST – case 19), infective IPT (case 30), and ischemic fasciitis (case 38). Substitutions at position 1807 of the BRAF gene were also detected in inflammatory fibroid polyps (cases 16 and 17) and IPTs (cases 27, 29 and 33).

Clonality

The NGS gene panel revealed clonality in a majority of the neoplasms studied. At least 1 gene variant with a VAF value greater than 0.5 or a functional gene rearrangement was identified in 50% of the neoplasms. Lower values of VAF and no functional rearrangement were found in 29% of patients. Only 21% of examined neoplasms did not present either mutation or rearrangement. Moreover, genetic alterations were identified in 82% of inflammatory lesions, cases with VAF values exceeding 0.5 in 18% of inflammatory lesions and with a VAF range of 0–0.5 in 64%. The OR for the presence of at least 1 functional rearrangement or genetic alteration with a VAF of 0.5 or higher in the neoplastic group compared to the reactive group was approx. 5.85. This result was statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (95% CI: 1.50–22.83, p = 0.011), calculated using the method described by Tenny et al.25

Clinical follow-up

The maximum observation for the study was 17 years. During this time, 10 patients (21.7%) died within a maximum of 6 years following the surgery. The causes of deaths were related to severe neoplastic diseases, including plasma cell myeloma (case 7), anaplastic meningioma (case 9), desmoid fibromatosis (case 12), angiosarcoma (case 15), and intestinal GIST (case 19). One patient (case 35) died post-surgery due to an abdominal aortic rupture. The overall odds of death were 0.33 in the neoplastic group and 0.22 in the reactive group.

During the surveillance period, which ranged from 1 to 13 years, 10 patients (21.7%) experienced local recurrence of their disease (Table 4). Nine of these cases were neoplastic in origin, including IMT (case 1), granular cell tumor (case 6), anaplastic meningioma (case 9), desmoid fibromatosis (case 12), sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma (case 13), intestinal GIST (case 19), spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (case 41), leiomyoma (case 43), and IMT/pseudosarcomatous myfibroblastic proliferation (PMP) (case 46). Episodes of double recurrence were observed in desmoid fibromatosis (case 12) and sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma (case 13). One reactive lesion, classified as infective IPT (case 31), also presented a recurrence. The overall odds of recurrence were 0.6 in the neoplastic group and 0.048 in the reactive group. The OR for recurrence (12.6) was statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (95% CI: 1.44–10.32, p = 0.022), calculated based on method described by Tenny et al.25 Four patients died following local recurrence, including those with anaplastic meningioma (case 9), desmoid-type fibromatosis (case 12), intestinal GIST (case 19), and infective IPT (case 31).

Patients diagnosed with IMTs survived until the end of the study with observation periods lasting between 1 and 8 years. Recurrence was noted in only 1 IMT with the EML4-ALK fusion gene (case 1), occurring 1 year after the initial surgery. No distant metastases were observed during the follow-up period.

Clinicopathological relation

Histopathological features and local recurrence

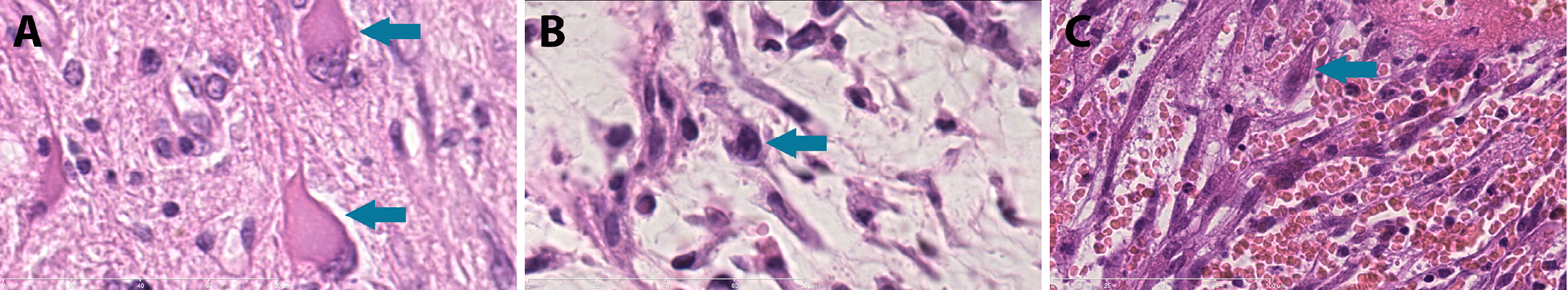

Ganglion-like cells were identified in specimens from 3 patients with recurrent neoplastic tumors (Table 4), including anaplastic meningioma of the right occipital region (case 9), desmoid fibromatosis of the right axillary region (case 12) and sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder (case 13) (Figure 6).

The OR for the presence of nuclear atypia in the group with recurrent disease compared to the non-recurrent group was 12, which was statistically significant at the 5% level (95% CI: 2.14–67.24, p = 0.005), calculated using the method described by Tenny et al.25 This suggests that nuclear atypia is associated with an adverse prognosis and an increased risk of disease recurrence. Four cases showed severe nuclear atypia (Table 4). Three of them, anaplastic meningioma of the right occipital region (case 9), sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder (case 13) and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx (case 41), presented recurrence. One patient with angiosarcoma of the ileum (case 15) died within 3 days after the operation. Desmoid fibromatosis (case 12) presented moderate atypia and recurred twice.

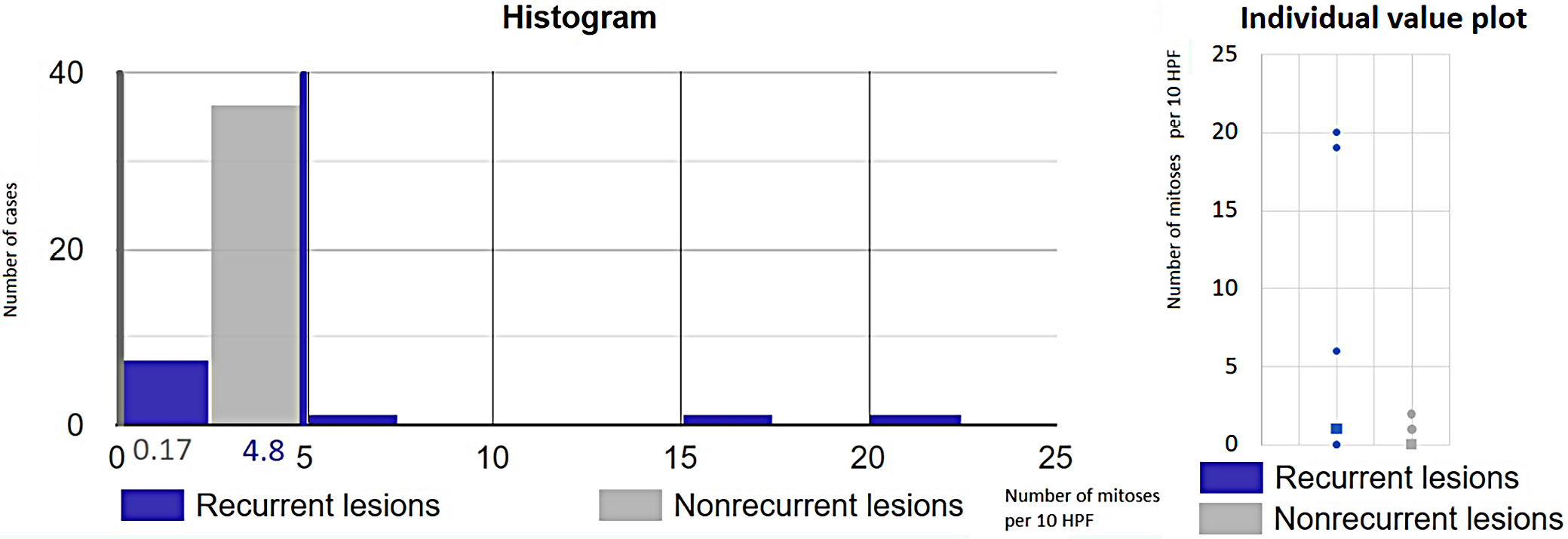

An increased mitotic rate (>5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) was observed in 3 recurrent cases: anaplastic meningioma (case 9), sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma (case 13) and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (case 41). Recurrence occurred in all 3 cases within 6 months (Table 4). Statistical analysis using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 269, p = 0.002) revealed a significant difference in mitotic index values between recurrent lesions (mean: 4.8/10 HPF) and non-recurrent lesions (mean: 0.17/10 HPF), confirming statistical significance at the 5% level (Figure 7).

Although no statistically significant relationship was found between necrosis and recurrence, the necrosis percentage differed significantly between patients who died during the study and patients who survived. It was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 253, p = 0.043), which showed a statistically significant difference between 1st (arithmetic mean: 22.3%) and 2nd group (arithmetic mean: 12.14%) at the 95% CI (Figure 8).

Genetic alterations and local recurrence

Disease recurrence was observed in 6 patients with identified genetic alterations (Table 2, Table 3). One IMT (case 1) harbored a fusion gene EML4-ALK and benign or uncertain mutations in the MET and RET genes. However, recurrences were not observed in case with other fusion genes. A recurrence was noted in intestinal GIST (case 19), which presented a likely pathogenic substitution in the MET gene. Four additional cases with genetic alterations of uncertain significance also experienced relapses. Notably, desmoid fibromatosis (case 12) and sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma (case 13), both with genes of unknown significance, exhibited double recurrence during the follow-up period.

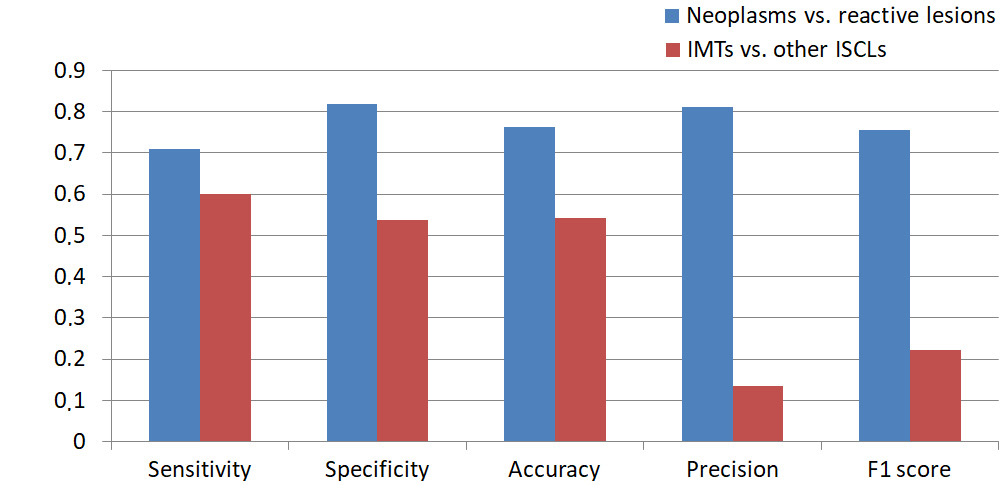

Diagnosis correctness verification

Following final diagnosis verification, patients were categorized into neoplastic and inflammatory groups (Table 5). Diagnostic accuracy for neoplasms was highly satisfactory with a sensitivity of 0.708, specificity of 0.818, accuracy of 0.761, precision of 0.81, and an F1 score of 0.756. Neoplastic lesions were subsequently classified into specific nosological entities. However, diagnostic performance for IMT was significantly lower with a sensitivity of 0.6, specificity of 0.537, accuracy of 0.543, precision of 0.136, and an F1 score 0.222 (Table 6, Figure 9).

Discussion

Inflammatory spindle cell lesions appear to represent an artificial and heterogeneous group of entities, and the term is rarely used in contemporary literature. Many distinct diseases can be differentiated from within this category.1, 2, 26, 27, 28 Establishing an accurate diagnosis is extremely challenging and requires clinicopathological correlation, genetic testing and considerable time, as also demonstrated by the findings of this study. Moreover, making a definitive diagnosis without ancillary tests is nearly impossible, as noted in previous reports.13, 19, 29, 30 Unfortunately, such diagnostic tools are typically available only in highly specialized medical centers. Therefore, the term “inflammatory spindle cell lesion” may be appropriately used in pathology departments with limited diagnostic resources, where molecular techniques are unavailable. However, the final diagnosis should ideally be confirmed in specialized soft tissue pathology centers using molecular assays.

Entities from the ISCL group are a rare occurrence, making it difficult to collect a sufficient number of cases to standardize research protocols.20 In this study, we aimed to gather as many tumors as possible and successfully included 46 cases. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) remains the most representative entity within the ISCL spectrum,1 which is why our focus was placed on investigating tyrosine kinase gene rearrangements. The final diagnosis of IMT requires a typical histopathological image and the presence of certain fusions. Detection of tyrosine kinase gene fusions using FISH, PCR or NGS plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the prognosis of IMT.20, 31 However, only NGS can provide comprehensive information about novel fusion genes.32, 33, 34

Interestingly, our cohort was predominantly composed of middle-aged and older adults, which contrasts with the typical age distribution reported for IMT in the existing literature.20 As the population ages, the prevalence of certain diseases increases, some of which can be severe and contribute to higher mortality. In older populations, comparing local recurrence rates is more relevant, as recurrence appears to be influenced by the final pathological diagnosis, anatomical location and type of surgical resection. Literature supports an association between these factors and local recurrence.35

In this study, primary histopathological diagnoses were compared to final diagnoses, which were based on clinical and paraclinical data. The results indicate that histopathological diagnostics are highly satisfactory for distinguishing between neoplastic and reactive lesions. However, primary recognition of IMT was inconsistent with the final diagnosis. The low values of precision, F1 score and sensitivity highlight the risk of diagnostic inaccuracies, even within academic medical centers. This aligns with prior publications highlighting the risk of misdiagnosis in histopathological evaluation of ISCLs.10, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Our findings underline the prevalence of this problem.

In IMT histopathological slides, the presence of intercellular mucus, ganglion-like cells, giant cells, necrosis, increased mitotic activity, and high cellularity are considered adverse prognostic factors.3, 42 In this study, local recurrences were observed in other neoplastic ISCLs containing ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity (Table 4). Statistical analysis revealed that the OR of these histological features significantly separated neoplastic from reactive groups within a 95% CI. Although no association was found between tissue pattern, necrosis or inflammatory infiltrate intensity and local recurrence as prognostic factors, a higher estimated necrosis percentage was observed in patients who died compared to those who survived with the difference being statistically significant. Thus, the presence of ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia, increased mitotic activity, and necrosis should be noted in pathological reports as negative prognostic factors.

No relationship between genetic changes and clinical outcomes was identified (Table 2, Table 3). Consistent with the literature, ALK gene fusions were the most frequent,20 present in 75% of IMTs confirmed with sequencing in this study (Table 2). Only 1 neoplasm (case 4) exhibited an NTRK3-rearrangement and EML4-ALK fusion genes were detected in 2 IMTs (cases 1 and 2). This fusion gene has also been identified in anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as colorectal and breast cancers.43 It contributes to tumorigenesis by producing a transcript that includes the intracellular kinase domain of ALK and the trimerization domain of EML4, enabling constitutive ALK activation through oligomerization and autophosphorylation. Tumors harboring this fusion are generally responsive to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.44

RANBP1-ALK, RANBP2-ALK and RRBP1-ALK rearrangements are characteristic of EIMS, a malignant IMT variant with an aggressive clinical course.31, 45 These fusions produce distinctive nuclear membrane or perinuclear accentuation patterns in ALK immunohistochemical staining.45 In case 3, the RANBP2-ALK gene was associated with focal nuclear membranous ALK positivity. Complete surgical removal of the neoplasm resulted in no recurrence over a 7-year follow-up period.

The ETV6 gene, a member of the ETS transcription factor family, regulates gene expression by nuclear binding. NTRK genes encode tropomyosin receptor kinases, which are crucial for neuronal tissue development and functioning.17, 28 The ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene has been detected in several neoplasms, including ALK-negative IMT, congenital infantile fibrosarcoma, acute myeloblastic leukemia, secretory breast carcinoma, mammary analog secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland, papillary thyroid carcinoma, and congenital mesoblastic nephroma.46 Differentiation between IMT and congenital infantile fibrosarcoma can be challenging, as both tumors may exhibit similar behavior. Histopathological features, such as classical pattern, inflammatory infiltrate and patients age above 1 year suggest an IMT rather than congenital infantile fibrosarcoma.47 Both tumors may also respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, underscoring the overlap in their management. Histologically, the term “inflammatory fibrosarcoma” has even been used synonymously with IMT.30

In the urinary bladder, pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations (PMPs) typically present grossly as nodular or polypoid ulcerative masses and exhibit microscopic features that closely resemble those of classical IMTs.48 Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations occur mainly in slightly older populations, are more cellular, and have shorter cells and fewer plasma cells than IMTs. While PMP tends to follow a slightly more aggressive course, both lesions can exhibit ALK fusions. However, the ALK breakpoint differs, being situated in exons 18 or 19 for PMP and exon 20 for IMT.9 In this study, differentiation between the 2 entities in case 46 was not possible due to low-quality RNA in the FFPE block. The histopathological findings and ALK-positivity in immunohistochemical assays were consistent with both entities (Figure 10). Treatment for PMP and IMT is similar,20, 48 and some authors consider them synonymous.49

Case 5 was ultimately diagnosed as a gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp containing the EGFR-PPARGC1A fusion gene. This rearrangement has previously been reported only in chronic sun exposure-related cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.50 In this case, the fusion appeared to be nonfunctional due to the absence of the EGFR gene promoter kinase domain (exon 20).51 In certain IMTs, the coexistence of an EML4-ALK rearrangement and an activating EGFR mutation plays a significant role in resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors.44 Since the EGFR gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 7 and the PPARGC1A gene on the short arm of chromosome 4, this fusion may result from a chromosomal translocation.

Indeed, IPT is thought to be a reactive lesion,1 but it can recur after surgical resection, especially when an incomplete excision is performed.51, 52 Moreover, if a causative agent persists in the organism, the recurrence may take place, as a result of ineffective antibiotic therapy in infections or insufficient suppressive treatment in autoimmune diseases. Such a situation was also observed in this study (case 31). However, the OR of relapse in our neoplastic compared to reactive group is approx. 12.6 and statistically significant within the 95% CI, which suggests local relapse tends to be more common for neoplasms.

In this study, neoplasms exhibited features such as ganglion-like cells, atypical cells and mitoses more frequently than reactive lesions. Ganglion-like cells, according to the literature, may occur in benign,53 intermediate and malignant neoplasms,54 but are also found in reactive lesions like proliferative myositis and necrotizing fasciitis.55 The presence of nuclear atypia is typically associated with a worse prognosis and is more commonly found in neoplastic lesions.56 In the neoplastic group, the presence of mitoses is associated with worse outcomes. Also, atypical mitotic figures can be found in neoplasms.57 Reactive lesions can also contain multiple mitoses, but are never atypical.58

Necrosis, calcifications and extravasated erythrocytes are rare in IMTs.59 Höhne et al. noted the presence of necrosis both in IMTs and IPTs but did not define a differentiating percentage.60 In this study, IMTs showed a significantly higher necrosis percentage than other ISCLs, as confirmed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Furthermore, a higher necrosis percentage was statistically associated with increased mortality.

Certain benign non-neoplastic lesions with histopathological features, like hypercellularity, cytological atypia and increased mitotic activity, are classified as psuedosarcomas.61 Integrating clinical and paraclinical data can help avoid misdiagnosing inflammatory lesions as sarcomas.

Interestingly, mutations were also observed in reactive lesions. While genetic clonality is a hallmark of neoplasms,47 clonal expansion is possible in non-cancerous lesions. The presence of driver mutations in these tissues may indicate an early tumorigenesis, which does not always progress to neoplasm development.62 Factors like aging, chronic inflammation and environmental exposures support clonal expansion.62, 63 Neoplasm development and progression require the accumulation of genetic mutations and epigenetic alterations, so a single change may not be sufficient to induce a real tumorigenesis.63 In this study, 82% of inflammatory lesions exhibited genetic clonality, which is consistent with this theory. The number of functional fusion genes with frequencies above 50% and variants with VAF values greater than 0.5 distinguished neoplastic from reactive lesions using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Limitations

This study has several limitations: 1) all cases were diagnosed within a single pathology department, potentially limiting generalizability; 2) only cases initially diagnosed as IMT or IPT were included, which may have introduced selection bias; 3) it was not possible to retrieve all FFPE blocks and histological slides; and 4) a limited targeted NGS gene panel was used. Detailed comparisons are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of integrating clinical and paraclinical data to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Prognosis is influenced more significantly by the final pathological diagnosis, anatomical location of the lesion and completeness of surgical resection than by isolated histopathological or genetic findings. However, neoplastic etiology and some of the features, such as the presence of ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity, can occur in lesions that present local recurrences. The study strongly supports the theory, which assumes that not only neoplasms but also reactive diseases can present worrisome histological features, pathogenic mutations and genetic clonality. However, neoplastic ISCLs more frequently exhibited ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia, elevated mitotic index, and the presence of functional gene rearrangements or point mutations with a VAF ≥ 0.5 compared to reactive lesions. Notably, both lesion types may recur if the underlying causative factor persists following excision. Among the detected functional gene rearrangements, the most frequent involved ALK and NTRK3 genes, which are considered key drivers in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.

Confirmation of tyrosine receptor kinase gene rearrangements is necessary for diagnosing IMTs, which showed a higher necrosis percentage than other ISCLs. A higher necrosis percentage was also linked to increased mortality. In summary, this study confirms the prognostic significance of a neoplastic diagnosis, presence of ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia, elevated mitotic index, and increased necrosis percentage. It also highlights the diagnostic value of ganglion-like cells, nuclear atypia, higher mitotic activity, and functional gene rearrangements or point mutations with a VAF ≥ 0.5. These features should be consistently reported in pathology assessments to support informed clinical decision-making.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15034538. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Full dataset of the study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.