Abstract

Background. Inflammatory response is involved in the pathogenesis of herpes zoster (HZ) and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

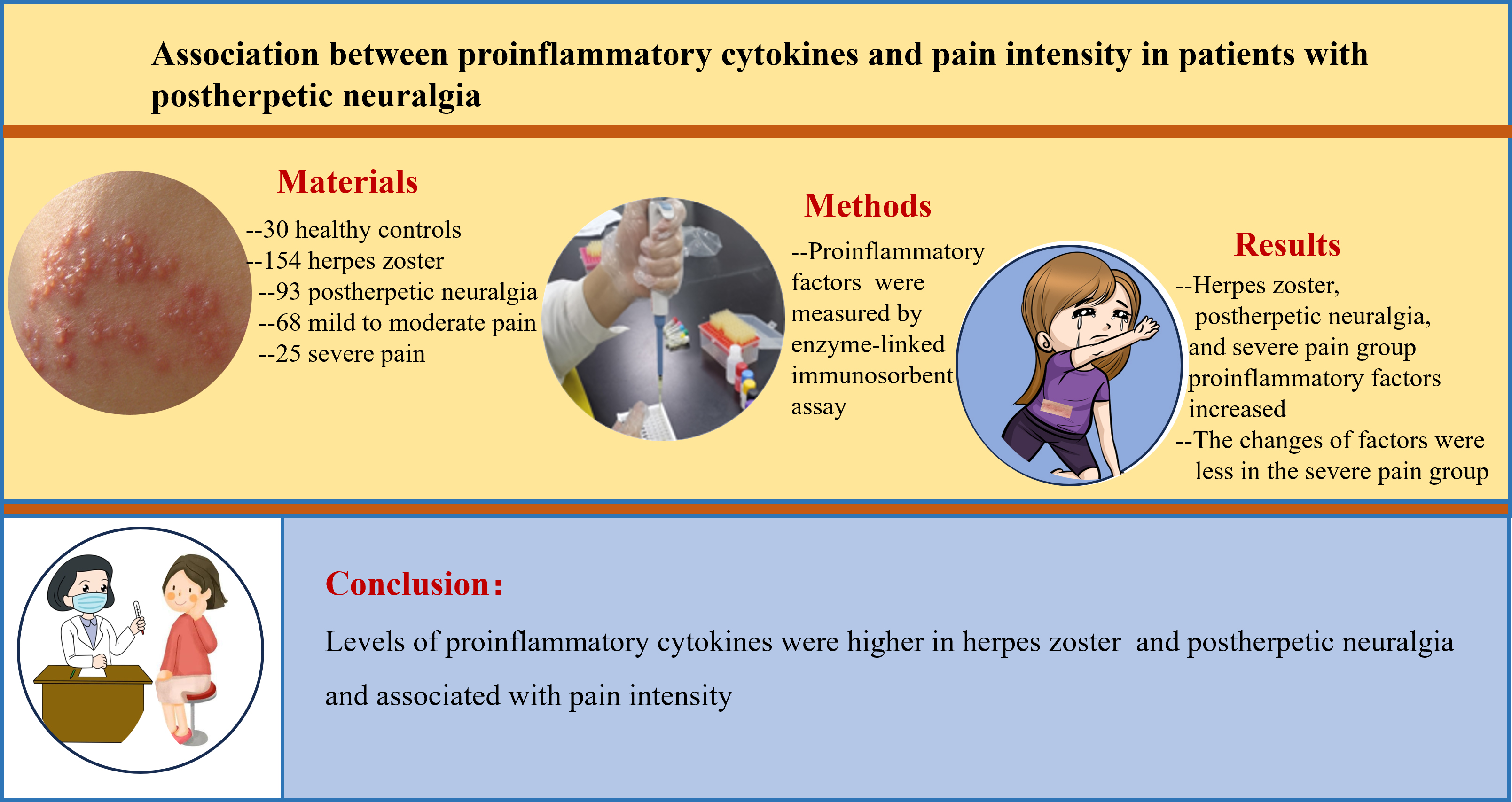

Objectives. This study aimed to evaluate levels of proinflammatory factors at different stages of HZ and PHN.

Materials and methods. A total of 154 patients within 72 h of HZ onset and 30 healthy controls were included. Patients were followed up to 90 days. The levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured at baseline and 90 days. The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to assess the intensity of pain and PHN patients were divided into mild-to-moderate pain and severe pain group.

Results. Interleukin 6, TNF-α and CRP levels in HZ patients at baseline were significantly higher than in healthy controls and decreased as followed up to 90 days. Moreover, PHN patients had a higher level of IL-6, TNF-α or CRP at baseline and 90 days than non-PHN patients. In addition, PHN patients in the severe pain group had a notably higher baseline or 90-day IL-6, TNF-α and CRP level than in the mild-to-moderate pain group. However, the changes of IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels between 90 days and baseline were significantly less pronounced in the severe pain group than in the mild-to-moderate pain group.

Conclusions. The levels of proinflammatory cytokines were higher in HZ and PHN patients and associated with pain intensity in PNH patients. These findings suggest that repeated measurements of serum proinflammatory cytokines may aid in clinical management and guide anti-inflammatory treatment strategies.

Key words: proinflammatory cytokines, interleukin 6, postherpetic neuralgia, tumor necrosis factor alpha, herpes zoster

Background

Herpes zoster (HZ), caused by varicella-zoster virus, is known as a common skin infectious disease and remains latent in the ganglia after the primary infection. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), a significant neuropathic complication of HZ, is clinically defined as persistent neuropathic pain lasting beyond 3 months.1 Recent studies indicated that the effectiveness of the live zoster vaccine wanes after 10 years in preventing HZ and PHN.2 Therefore, emerging evidence underscores the necessity of developing multimodal therapeutic interventions targeting both HZ and PHN. Previous studies suggest that combination or interventional therapies may benefit patients with intractable conditions.3, 4, 5 Yet, the incidence of HZ and its sequela, PHN, has continued to rise,6 with the risk of PHN increasing sharply with age.7 Therefore, elucidating the underlying pain mechanisms is essential for developing novel treatment options.

Multiple immune cells (mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and T lymphocytes) and their secreted mediators contribute to the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain.8, 9 Since proinflammatory cytokines are central to these inflammatory pathways, a broader panel of pertinent biomarkers should be assessed in patients with HZ and PHN.

Proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP), have a trending relationship with pain condition.10, 11 Previous studies also indicated that IL-6 levels were related to the severity of PHN.12 Compared to non-PHN patients, CRP level increased in PHN patients.13 Furthermore, recent studies indicated that TNF-α produced by varicella-zoster virus-specific T cells was higher in PHN patients.14

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the levels of IL-6, TNF-α and CRP at different stages of HZ and PNH.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Huabei Petroleum Administration Bureau General Hospital (approval No. EC-2023-hbyyecky-01) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria for patients with HZ were: 1) fulfilment of the diagnostic criteria for HZ; 2) no speech or cognitive impairment; and 3) capacity to understand and use the visual analogue scale (VAS).

Exclusion criteria were: 1) age <18 or >80 years; 2) concomitant autoimmune disease, including ankylosing spondylitis; 3) active malignancy, bacterial or viral infection other than HZ, or related disorders; 4) recent use of immunosuppressants; 5) severe systemic comorbidities involving the nervous, cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal systems; and 6) pregnancy or lactation.

Patients with HZ and PHN were administered appropriate comprehensive treatment, including oral valaciclovir, gabapentin and mecobalamin. All patients were followed up for 90 days. Trained clinical professionals conducted face-to-face follow-up visits with the patients. The VAS questionnaire was used to evaluate the pain intensity, ranging from 0 to 10. The VAS pain scale was used as in earlier studies: 0 = no pain; 1–3 = mild, tolerable pain; 4–6 = moderate pain that disrupts sleep; and 7–10 = severe, intolerable pain that interferes with both sleep and appetite.15, 16

Patients with PHN were stratified by VAS score: a VAS ≤6 defined mild-to-moderate pain (n = 68), whereas a VAS >6 indicated severe pain (n = 25).

Data collection

Baseline demographic and clinical data were recorded within 24 h of admission, including histories of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Serum biomarkers (IL-6, TNF-α and CRP) were also measured.

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or current use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed by a fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, an HbA1c ≥6.5 %, a 2-h plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L during an oral glucose-tolerance test, or current antidiabetic therapy. Dyslipidemia was defined as a fasting total cholesterol ≥5.2 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≥3.4 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <1.0 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L, or current use of lipid-lowering agents.

Biochemical measurements

Serum samples from HZ patients and healthy controls were collected at enrollment and again 90 days later, aliquoted into cryotubes, and stored at −80°C without any freeze–thaw cycles. Concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α and CRP were quantified with commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (RapidBio, Arizona, USA) by laboratory staff blinded to the clinical data. Each assay was run in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Study size

Between January 2020 and December 2022, 154 patients seen within 72 h of HZ onset and 30 healthy controls were enrolled.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants were described as frequencies (percentages) and median with interquartile range (IQR; Q1–Q3). The variables included gender, age, a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. Significant differences between the 2 groups were tested with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Paired cytokine concentrations in HZ patients (baseline vs day 90) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Baseline HZ patients vs healthy controls, and day-90 HZ patients vs healthy controls, were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test, applying a Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = 0.025). All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

From 2020 to 2022, 154 patients and 30 healthy volunteers were enrolled. The HZ and control groups did not differ in age or sex. The patients’ median age was 67 years, and 52 (33.8 %) were women. Baseline median serum concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α and CRP were 6.23 pg/mL (IQR: 4.63–9.55), 8.43 pg/mL (IQR: 7.34–9.95) and 12.98 mg/dL (IQR: 11.89–14.69), respectively.

Evaluation of proinflammatory cytokines in HZ patients and healthy controls

To investigate the differences of proinflammatory cytokines between HZ patients and healthy controls, we measured the IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels. We found that proinflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in HZ patients than in healthy controls (all p < 0.001) (Table 1). Subsequently, to further assess the differences in proinflammatory cytokine levels across different stages of HZ, we measured serum IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels in HZ patients at 90 days. We found that the 90-day levels of these proinflammatory cytokines had significantly decreased compared to baseline (all p < 0.001; Table 1). However, IL-6 and CRP levels at 90 days remained significantly higher than those observed in healthy controls (both p < 0.001).

Evaluation of proinflammatory cytokines with PHN patients

The demographic and clinical characteristics of PHN and non-PHN patients are presented in Table 2. Among the 154 patients, 93 (60.4%) had PHN, while 61 (39.6%) did not. The PHN patients were generally older, with a higher proportion of males, and showed a higher prevalence of preexisting comorbidities, particularly hypertension and diabetes mellitus. We examined the relationship between baseline proinflammatory cytokine levels and pain intensity in PHN patients (Table 2). As shown in Figure 1, serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines were markedly higher in PHN patients compared to non-PHN patients. Furthermore, at 90 days, the levels of these cytokines remained significantly elevated in PHN patients (Figure 1).

Association between serum proinflammatory cytokines and VAS score

The demographic and clinical characteristics of PHN patients in relation to VAS scores are presented in Table 3. Among the 93 PHN patients, 68 (73.1%) were classified as having mild-to-moderate pain, while 25 (26.9%) had severe pain. Compared to those with mild-to-moderate PHN, patients with severe PHN were more likely to be older and female and to have a history of diabetes mellitus.

We examined the relationship between proinflammatory cytokine levels and pain intensity in PHN patients (Table 3). As shown in Figure 2, baseline levels of proinflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in patients with severe pain compared to those with mild-to-moderate pain. Furthermore, at 90 days, cytokine levels remained notably higher in the severe pain group compared to the mild-to-moderate pain group (Figure 2).

Changes of proinflammatory cytokines in different pain intensity PHN

To investigate the changes in proinflammatory cytokine levels across different phases in PHN patients, we further analyzed the differences between baseline and 90-day measurements according to pain intensity (Table 4). The results showed that the reduction in proinflammatory cytokine levels over time was smaller in PHN patients with severe pain compared to those with mild-to-moderate pain.

Discussion

In this study, we found that serum proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with HZ were significantly higher than those in healthy controls. Furthermore, cytokine levels showed a significant decrease at 90 days compared to baseline. Additionally, serum proinflammatory cytokine levels were notably higher in PHN patients compared to non-PHN patients. We also observed that cytokine levels were associated with pain intensity, and the degree of change in serum cytokine levels over time was related to pain intensity as measured using VAS scores.

Interleukin 6 is a key immunomodulatory cytokine that plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory conditions.17 Previous studies have confirmed that blocking the IL-6 pathway is an effective immunotherapeutic strategy.18, 19Recent research has further demonstrated that targeting the IL-6 pathway, either by interfering with IL-6 itself or its specific receptor, has become a major approach to alleviating inflammatory responses.20 Additionally, IL-6 levels have been shown to decrease following treatment in PHN patients.21 Other immune cytokines, such as TNF-α, which regulate both acute and chronic inflammation, also play crucial roles in signal transduction under certain conditions.22, 23

Monoclonal antibodies have been used to antagonize the TNF-α pathway in inflammatory diseases.24, 25, 26 However, a recent study indicated that TNF-α levels were lower in PHN patients.27 Additionally, CRP, which is secreted in response to IL-6 stimulation, may serve as a more sensitive biomarker for detecting systemic inflammation following inflammatory events. In turn, CRP interacts with various cell types and stimulates the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby promoting proinflammatory effects.28 Growing evidence has shown that CRP levels are associated with inflammation and disease activity.29 Furthermore, pharmacological treatments for immune-mediated systemic inflammatory diseases generally reduce systemic inflammation, with CRP levels typically decreasing in accordance with the drug’s mechanism of action.28

Previous studies have found that CRP levels increase in both HZ and PHN patients and decrease after treatment.13, 30 In summary, although immunological responses are thought to mediate the clinical features of HZ and PHN,31 the association between serum IL-6, TNF-α or CRP levels and pain intensity in PHN remains not well established. Some studies have shown that IL-6 and CRP levels in HZ patients within seven days of onset are higher than in healthy controls, with these differences potentially linked to pain severity.32 Additionally, it has been suggested that serum IL-6 levels might serve as a predictor of PHN severity.12 In contrast, other studies have reported that IL-6 receptor α levels are significantly downregulated in PHN patients compared to healthy controls.15

In addition, recent studies with small sample sizes have shown that the concentration of TNF-α secreted by varicella-zoster virus-specific T cells is higher in PHN patients than in non-PHN patients, highlighting the potential role of these specific T cells in the development of PHN.14 However, further investigation into the interactions among multiple inflammatory factors in HZ and PHN is needed to better understand their combined effects. Moreover, given the large sample size in this study, even minor differences may reach statistical significance. Therefore, additional research is required to clarify the association between proinflammatory cytokines and pain intensity in PHN patients.

In our study, we examined serum proinflammatory cytokine levels in HZ patients within 72 h of onset and in PHN patients at 2 different phases. Additionally, we analyzed whether changes in proinflammatory cytokine levels were associated with pain intensity. We found that serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines in HZ patients were significantly higher at baseline compared to healthy controls and decreased over the 90-day follow-up period. Furthermore, elevated serum levels of these cytokines were associated with the pain intensity observed in PHN patients. Notably, the reduction in cytokine levels between baseline and 90 days was smaller in PHN patients with severe pain compared to those with mild-to-moderate pain.

Since levels of inflammatory factors change dynamically throughout disease progression, examining these markers at different phases of PHN may help improve our understanding of their relationship with pain intensity. Consistent with previous studies,12 we found that IL-6 levels significantly decreased at 90 days compared to baseline. However, to date, no studies have assessed serum IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels both at baseline and at 90 days to explore their association with pain intensity in PHN patients. Our study demonstrated that both baseline and 90-day proinflammatory cytokine levels were elevated in HZ patients and were closely associated with pain intensity in those with PHN.

Several mechanisms might explain this finding. One possible explanation is that pro-nociceptive cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, promote the activation of nociceptor neurons.33, 34 Previous studies have indicated that macrophages play a key role in both pathological and physiological pain by releasing the nociceptive cytokine IL-6.35 Additionally, macrophages can regulate the threshold for pain perception by secreting nerve growth factor into the dermis.36 Another possible explanation is that immune cells and neurons interact to modulate pain sensitivity, contributing to the transition from acute to chronic pain.37

Previous studies have suggested that the application of TNF-α can cause axons to produce aberrant electrophysiological activity, and this subsequent ectopic firing by nociceptive axons may generate pain sensations through activation of dorsal horn neurons.38 Another explanation is that serum CRP levels are higher in HZ patients with severe rash compared to those with mild or moderate rash.13 Consistent with prior findings, severe rash was significantly associated with severe pain in both univariate and multivariate analyses, indicating that the severity of rash is an important risk factor for pain intensity in PHN patients.39

Considering the dynamic changes of inflammatory markers involved in pain sensation,40 we further evaluated the association between changes in serum proinflammatory cytokine levels (from baseline to 90 days) and pain intensity. To date, these associations with pain intensity in PHN patients have not been clearly defined. We found that smaller reductions in IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels were associated with an increased risk of severe pain. Therefore, repeated measurements of serum proinflammatory cytokines should be considered in the clinical management of HZ and PHN patients. Our findings suggest that appropriate anti-inflammatory treatments – particularly targeting IL-6, TNF-α and CRP – may help reduce the risk of developing severe pain in HZ patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we focused only on IL-6, TNF-α and CRP, while other proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators may also play important roles in pain intensity among PHN patients. Second, we measured serum levels of inflammatory factors without investigating their cellular sources, which could provide deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms. Future studies exploring the origin of these inflammatory mediators may help clarify their specific contributions to pain intensity. Third, we assessed inflammatory factor levels at only 2 time points; more frequent, dynamic measurements over time could offer a better understanding of the temporal relationship between inflammatory responses and pain. Future research should include a broader panel of inflammatory mediators, track their dynamic changes over multiple time points, and explore their cellular origins to provide more precise mechanistic insights and strengthen the biological relevance of the findings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines are associated with pain intensity in patients with PHN. Furthermore, patients with severe pain showed smaller reductions in proinflammatory cytokine levels between baseline and 90 days, suggesting a link between sustained inflammation and pain severity.

Data availability statement

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/MiaoJun2024/Data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.

.png)

.png)