Abstract

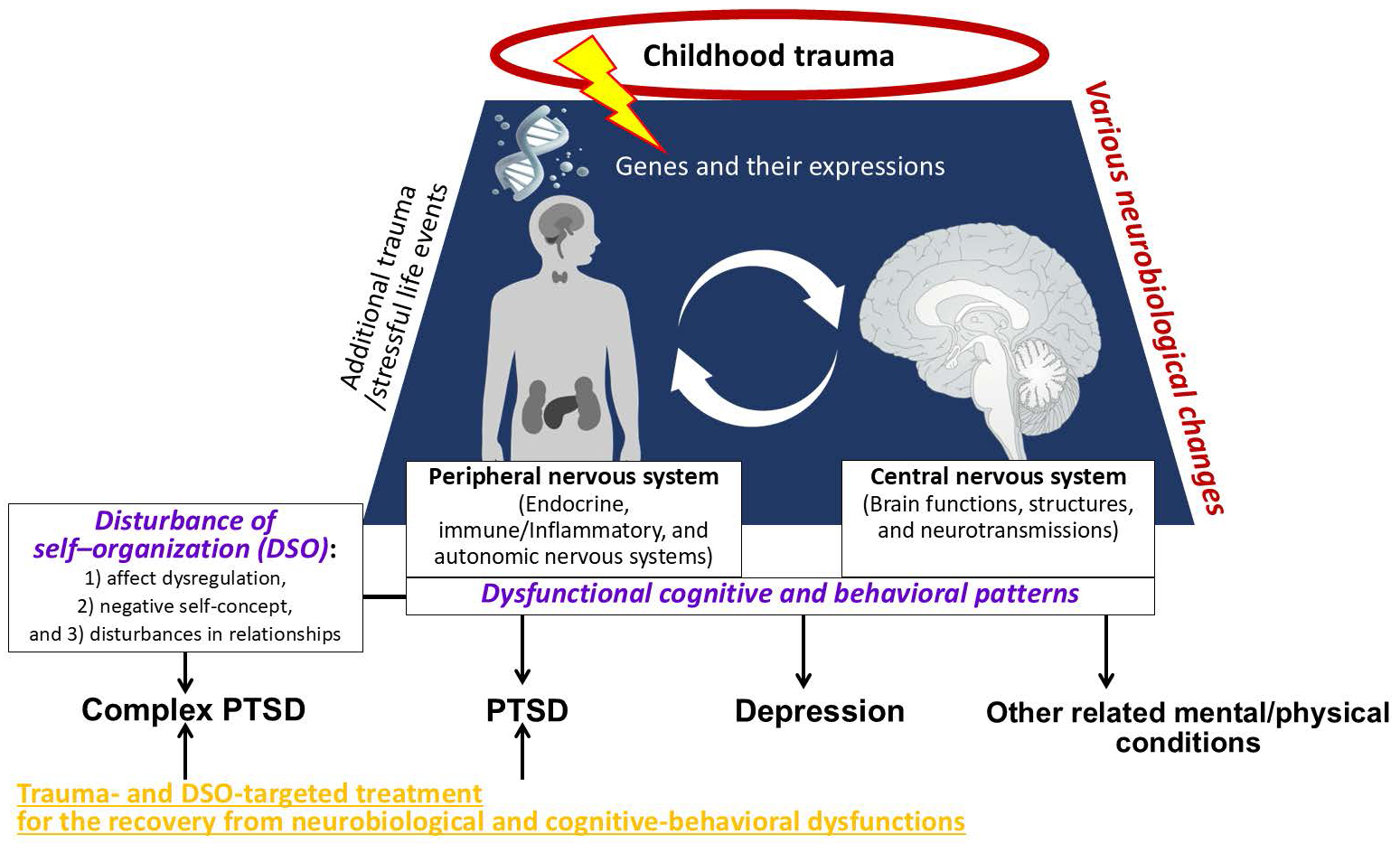

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as childhood abuse and neglect, have a profound impact on our bodies, affecting the brain, autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, immune and inflammatory systems, as well as genetic expressions. Childhood maltreatment can leave long-lasting neurobiological scars, significantly increasing the risk of developing both physical and mental disorders, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The ICD-11, an international disease classification system, has recently introduced new diagnostic criteria for what is known as complex PTSD. In this context, we will briefly overview the neurobiological effects of ACEs, the associated health conditions they can lead to, and potential pathways to recovery. These pathways include promoting the reinstatement of emotional and interpersonal skills that may have been impaired during early development. Approaching ACEs from a holistic perspective may open new avenues for more effective clinical practices for individuals suffering both physically and mentally.

Key words: childhood trauma, childhood adverse experiences (ACEs), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), complex PTSD, evidence-based psychotherapy

Introduction

Medicine is the science and practice of diagnosing, treating, managing, and preventing diseases, injuries, and related health conditions in humans. Clinicians recognize the importance of viewing diseases and health problems from a holistic, biopsychosocial framework. For example, the cause of a liver disease can be attributed to habitual excessive alcohol intake. In that case, we need to consider and address the maladaptive alcohol intake in treating the disease itself. External stressors (e.g., pathogens, allergens and harmful substance exposure) have, of course, detrimental effects on the body, but scientists have revealed that psychological stressors, such as trauma, also significantly affect our physical conditions – the brain, autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, immune/inflammatory system, and gene expressions.

Unfortunately, in psychiatry, there is no established objective marker to determine the presence of mental illnesses. Stressful life events and dysfunctional family environments often precede the development of psychiatric diseases; however, it is challenging to clarify the causal relationship between them. Thus, psychiatric diagnoses are primarily based on the information collected during a medical interview, including the types and duration of symptoms that the patient experiences. Among these conditions, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is unique in that its diagnostic criteria explicitly require exposure to a life-threatening event – a clearly defined environmental factor. Such traumatic events include combat experience, natural disaster, motor vehicle accident, and sexual assault.

Recently, the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11), introduced new diagnostic criteria for complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). It is a disease strongly associated with long-term, repeated traumas, rather than a single trauma, which include adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as abuse and neglect from a principal caregiver. Notably, ACEs are one of the most serious social problems, affecting over 1/3 of the population in developed countries, as indicated by extensive epidemiological studies.1 In addition, physically and sexually abused individuals are reported to have a 40% prevalence rate of CPTSD.2 Its diagnostic criteria consist of the disturbance of self-organization (DSO), in addition to 3 PTSD criteria of trauma re-experience, avoidance and sense of threat. Disturbance of self-organization further has 3 types of symptoms: 1) affect dysregulation (e.g., sudden outbursts of anger and intense mood swings), 2) negative self-concept (e.g., feeling of self-worthlessness) and 3) disturbances in relationships (e.g., overdependence on or overavoidance from others). It can overlap with the symptoms of attachment disorders and borderline personality disorder.3

Here, we provide a brief overview of the neurobiological impacts of ACEs, the associated health conditions, and possible pathways to recovery, with a focus on CPTSD.

ACEs and neurobiological scars

Substantial evidence indicates that, irrespective of the presence or absence of psychiatric diagnosis, individuals with ACEs exhibit blunted cortisol responses to psychosocial stressors, and increased levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP). In addition, they show exaggerated amygdala responses to emotionally negative stimuli and possess decreased hippocampal grey matter volume (see Hakamata et al.4 for a comprehensive review).

Although the mechanisms underlying these neurobiological alterations remain unclear, animal studies have reported elevated glucocorticoid and glutamate levels, as well as overactivation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, in mice exposed to repetitive stressors during early development. Among them, NMDA receptor overstimulation is known to cause neuronal death, inhibit neurogenesis, and reduce dendritic branching in the hippocampus.5 In contrast, decreased cortisol secretion is observed in adults who have experienced ACEs,6 which initially seems to contradict the findings on excessive glucocorticoid secretion in animal studies. However, cortisol levels may have similarly increased in humans who experienced ACEs at certain points in early life, potentially leading to disruptions in neuronal growth and generation in the hippocampus, as well as dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Supporting this notion, a few longitudinal studies demonstrated the decline of cortisol levels over time in adolescents with ACEs,7, 8 while their CRP levels increased as time passed,9 suggesting low-grade inflammation caused by blunted cortisol secretion. Furthermore, peripheral inflammatory markers can penetrate the blood–brain barrier when systemic inflammation persists,10 exerting detrimental effects on the central nervous system through multiple pathways.11

Importantly, ACEs increase the risk of developing stress-related mental disorders such as PTSD and depression by approx. 4–5 times.12, 13 In addition, childhood maltreatment confers a 1.5-fold increased risk of lung disease, gastric ulcers, and arthritis. Sexual abuse increases the risk of heart diseases by about 4 times, and neglect increases the risk of autoimmune diseases by 4 times.14

The neurobiological alterations associated with ACEs can exist transdiagnostically and lead to the development or the increased risk of mental (and/or physical) diseases through complex interactions between various environmental and genetic factors. Future research should elucidate the neurobiological alterations and the pathways leading to each medical disease.

Recovery from ACEs

The diagnostic notion of CPTSD is relatively new, and systematic research on its effective treatment is still underway. However, according to a meta-analysis on previous randomized controlled trials for PTSD patients with at least 1 symptom among the DSO (i.e., CPTSD syndrome), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure component alone (EA) and eye movement and desensitization reprocessing (EMDR), which are evidence-based psychological treatments for PTSD, improve interpersonal difficulties with moderate-to-large effect sizes.15 Despite the lack of EMDR findings, CBT and EA also alleviate negative self-concept with moderate-to-large effect sizes. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of treatments for affect dysregulation remains unclear.

Recently, the Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR) Narrative Therapy,16 developed for childhood trauma survivors, has attracted significant attention as a new, promising treatment for DSO in CPTSD. STAIR Narrative Therapy consists of 16 sessions, including skills training in affect regulation and interpersonal difficulties (i.e., STAIR), and repeated imaginal exposure to trauma with cognitive restructuring (i.e., Narrative Therapy). Narrative Therapy is similar to CBT and exposure therapy, which encourage patients to recall trauma memories vividly and repeatedly and thereby help them integrate fragmented memories into a part of their autobiographical memory in a less threatening manner through cognitive restructuring.17 The key feature of this psychotherapy is that it includes the component of STAIR to develop and strengthen patients’ skills to be aware of, accept and manage their feelings and emotions, and express them more adaptively. The STAIR is also similar to the emotion regulation group therapy,18 whose effectiveness has been shown in patients with borderline personality disorder with significant problems in regulating their intense emotions.19 STAIR focuses on the recovery and redevelopment of emotional and interpersonal skills impaired due to chronic childhood abuse, and has been demonstrated to effectively improve CPTSD symptoms, including DSO.20, 21

A meta-analysis, although a preliminary quantitative synthesis, has found that evidence-based PTSD psychological treatments reduced the exaggerated amygdala activity towards negative stimuli, accompanying decreased activity in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex, in PTSD patients.22 These findings suggest that individuals with ACEs can recover from the neurobiological scars they have sustained. Future research should elucidate the neurobiological mechanisms by which STAIR Narrative Therapy or other potential treatments can ameliorate DSO, addressing the difficulties stemming from ACEs.

Conclusions

Clinicians and scientists find essential to consider the effects of psychosocial stressors that significantly affect our mind and body – from the brain, autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, immune/inflammatory system, up to gene expressions – especially for individuals with ACEs associated with various mental and physical health problems towards better medical practice, holistic treatment, and support for them.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.