Abstract

Background. Dendritic cells (DCs) are a key class of immune cells that migrate to the draining lymph nodes and present processed antigenic peptides to lymphocytes after being activated by external stimuli, thereby establishing adaptive immunity. Moreover, DCs play an important role in tumor immunity.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to investigate whether MCT1 gene silencing in DCs affects their ability to mount an immune response against cervical cancer cells.

Materials and methods. We silenced the expression of MCT1 in DCs from mouse bone marrow (BM) by infection with adenovirus. The surface antigen profile of DCs was analyzed by flow cytometry and cytokine secretion was evaluated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following sodium lactate (sLA) exposure and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. Then, various groups of DC-induced cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) were prepared and their cytotoxicity against U14 was tested.

Results. Without sLA exposure, silencing MCT1 did not affect the expression of CD1a, CD80, CD83, CD86, and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) in DCs after LPS challenge. Similar results were found for interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12 p70 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). After sLA exposure, silencing MCT1 significantly decreased the expression of CD1a, CD80, CD83, CD86, and MHCII in DCs after the LPS challenge, as well as the secretion of IL-6, IL-12 p70 and TNF-α. In addition, sLA exposure significantly reduced the toxicity and inhibited the proliferation of DC-induced CTLs compared to U14 cells in vitro and in vivo. However, silencing MCT1 significantly attenuated the changes caused by sLA exposure. At the same time, in the absence of sLA, silencing MCT1 did not affect the toxicity nor inhibit the proliferation of DC-induced CTLs on U14 cells.

Conclusions. Lactate exposure reduces the immune effect of DCs on cervical cancer cells, but MCT1 gene silencing attenuates these alterations.

Key words: dendritic cells, cervical cancer, immunity, MCT1

Background

Dendritic cells (DCs) represent a critical subset of immune cells that initiate adaptive immunity by migrating to the draining lymph nodes. These cells are activated by external stimuli and present processed antigenic peptides to lymphocytes.1, 2 Moreover, DCs play an essential role in tumor immunity by ingesting tumor antigens and maturing to express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, costimulatory factors, and adhesion factors.3, 4 In addition, DCs combined with T cells induce the killer cells to produce large quantities of interferon (IFN)-γ, perforin and granzyme by secreting high concentrations of interleukin (IL)-12, thereby enhancing the lysis effect of target cells on cancer cells.3, 4 Simultaneously, DCs can induce the killing effect of CD8+ T cells, facilitating the clearance of antigen-specific tumor cells. Thus, DCs initiate the body’s anti-tumor immunity and are the bridge between T cells and tumor cells.5, 6 Any alteration to the normal functioning of DCs can directly impact the body’s anti-tumor immunity.

Tumor immunotherapy, especially chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell immunotherapy, has developed rapidly in recent years.7 Despite significant clinical outcomes of immunotherapies in liquid tumors, their effectiveness in solid tumors is comparatively limited. The microenvironment of solid tumors has been identified as a key factor contributing to the significant difference in clinical responses to cell-based immunotherapy between these two forms of cancers.7, 8 The Warburg Effect is the most notable feature distinguishing tumor cells from normal cells, in which tumor cells preferentially choose to supply energy through glycolysis under anaerobic conditions, and lactate is the main by-product of glycolysis energy supply for tumor cells.9, 10 The Warburg Effect may provide tumor cells with an escape mechanism against the immune system, as high lactate concentrations have been reported to alter the phenotype of immune cells.11, 12, 13 A recent study stated that lactate exposure attenuated DC maturation by downregulating CD80 and MHCII expression following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation.13 Therefore, lactate is a barrier affecting the anti-tumor immunity of DCs.

Monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) of the SLC16 solute carrier family are key proteins for intracellular and extracellular lactate exchange.14, 15, 16 Under physiological conditions, MCTs prevent lactate accumulation within cells by eliminating its excess produced due to increased glycolytic activity. This process has potential implications for developing cancer therapeutics targeting lactate metabolism.16, 17 Dendritic cells express several MCTs, including MCT1, MCT2 and MCT4. The MCT1 and MCT2 are responsible for transporting extracellular lactate into the cell, while MCT4 is responsible for transporting intracellular lactate outside the cell.

Additionally, while MCT1 and MCT4 are regulated by lactate, MCT2 is not involved in lactate management.13, 15, 18 Therefore, we hypothesized that the expression level of MCT1 in DCs would have an impact on their phenotype under high lactate conditions, thereby affecting their anti-tumor immunity. In this study, we used adenovirus to silence MCT1 of mouse bone marrow (BM)-derived DCs to investigate their phenotypic changes and toxicity to cervical cancer cells in standard or high lactate environments.

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the impact of DC-mediated immunity on cervical cancer cells following MCT1 gene silencing.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out following the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.19 The protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, Naval Medical University, China (approval No. 2017KY068).

Cells and reagents

The U14 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (A1049101; Gibco, Waltham, USA) with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10099141; Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Mouse SLC16A1 (MCT1) shRNA silencing adenovirus (Ad-shMCT1) and its matched control shRNA adenovirus were purchased from Vector Biolabs (shADV-272089; Vector Biolabs, Malvern, USA). The anti-MCT1 antibody was purchased from Abcam (ab156080; Cambridge, UK). Other used antibodies included FITC-conjugated CD1a antibody (ab27992; Abcam), CD80 antibody (ab18279; Abcam), CD83 antibody (MHCD8301; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), CD86 antibody (MHCD8601; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and MHCII antibody (11-9956-42; eBioscience, San Diego, USA). The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (C0037), mouse IL-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (PI326) and mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) ELISA kit (PT512) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Finally, the mouse IL-12 p70 ELISA kit (EK0500) was purchased from Signalway Antibody (Greenbelt, USA).

Adenovirus infection of BM-derived DCs

As previously described,20 we prepared DCs from mouse BM. In brief, the mouse tibia was rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), red blood cells were fully lysed, and cells were collected by centrifugation. The cells from BM were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 ng/mL rmGM-CSF (PMC2016; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 20 ng/mL rmIL-4 (RMIL4I; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 week. Subsequently, Ad-shCtrl or Ad-shMCT1 adenoviruses (MOI = 10:1) were added to BM-derived DCs for 12 h, cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then, the medium was replaced with a fresh one to continue culturing.

Immunoblot analysis

After 24 h of Ad-shCtrl or Ad-shMCT1 infection, DCs were harvested, and an appropriate amount of cell lysing solution was utilized to extract total cellular protein. Approximately 40 μg of cellular protein was analyzed using 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by the transfer of protein molecules to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Subsequently, the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk powder at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the MCT1 antibody. After being washed 3 times with tris-buffered saline (TBS)+0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) buffer at room temperature, secondary antibodies were added to the membrane and it was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were developed using an ECL Chemiluminescence Kit (P0018FS; Beyotime), and the protein band grey value was analyzed using ImageJ v. 1.8.0 (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

Dendritic cell phenotype analysis and cytokine assay

After 24 h of Ad-shCtrl or Ad-shMCT1 infection, 50 mM of sodium lactate (sLA) was added to the culture medium for 48 h (an equal amount of PBS was used as control) and then changed to a fresh medium supplemented with 1 µg/mL LPS (L2880; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), followed by culturing for another 24 h. Then, we collected DCs and analyzed their phenotype using a flow cytometer. The cell culture medium was collected and investigated for cytokine content (IL-6, IL-12 p70 and TNF-α), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

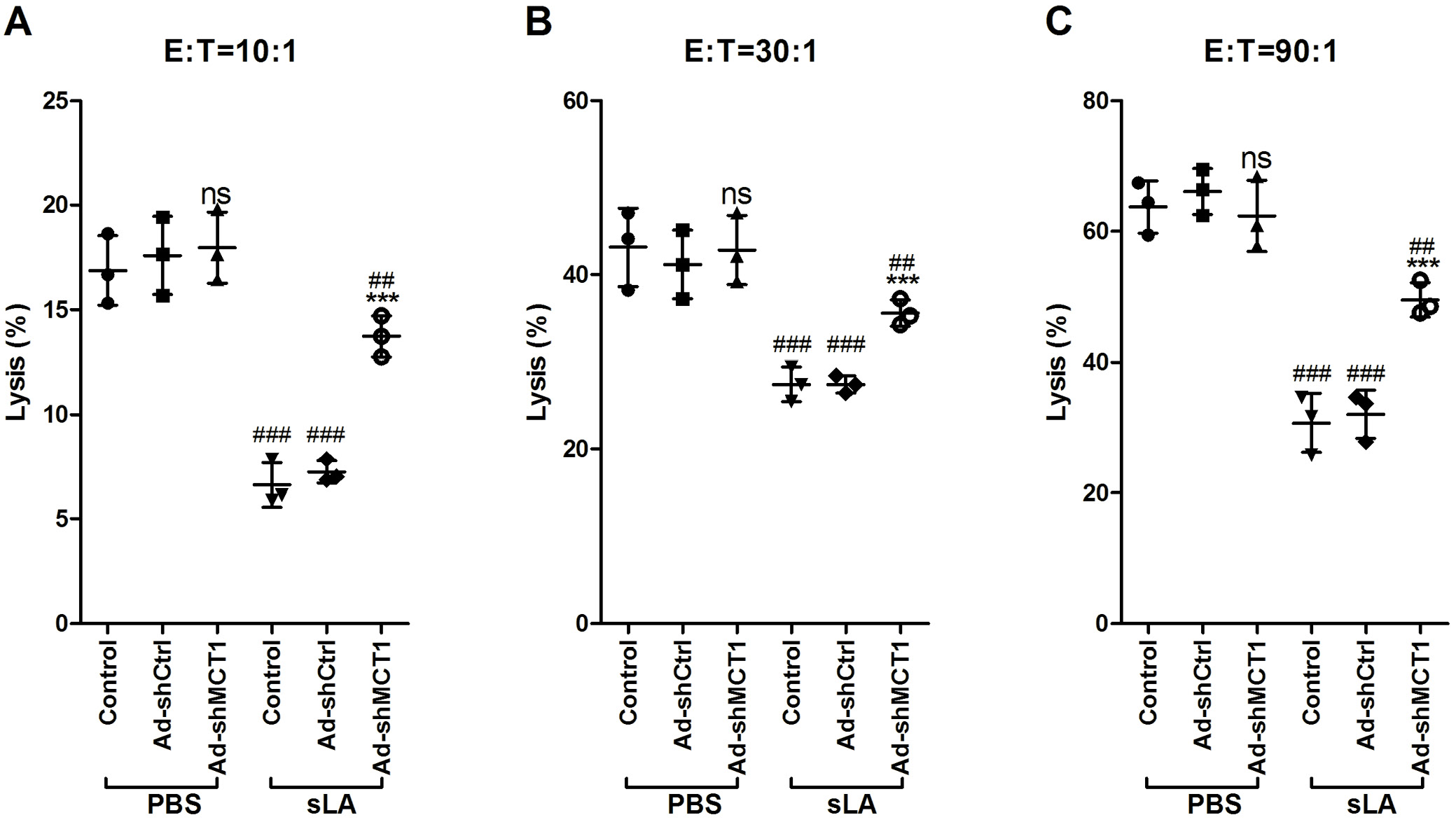

Cytotoxicity assay

Dendritic cells were co-cultured with mouse splenic T cells for 1 week at a ratio of 1:10 after adenovirus infection, sLA exposure (PBS as control) and LPS challenge. Then, we collected the T cells after 7 days, defining them as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Using a CCK-8 kit, the in vitro cytotoxicity of DC-induced CTLs was assayed by culturing the CTLs with target U14 cells for 24 h at effector:target (E:T) ratios of 90:1, 30:1 and 10:1.

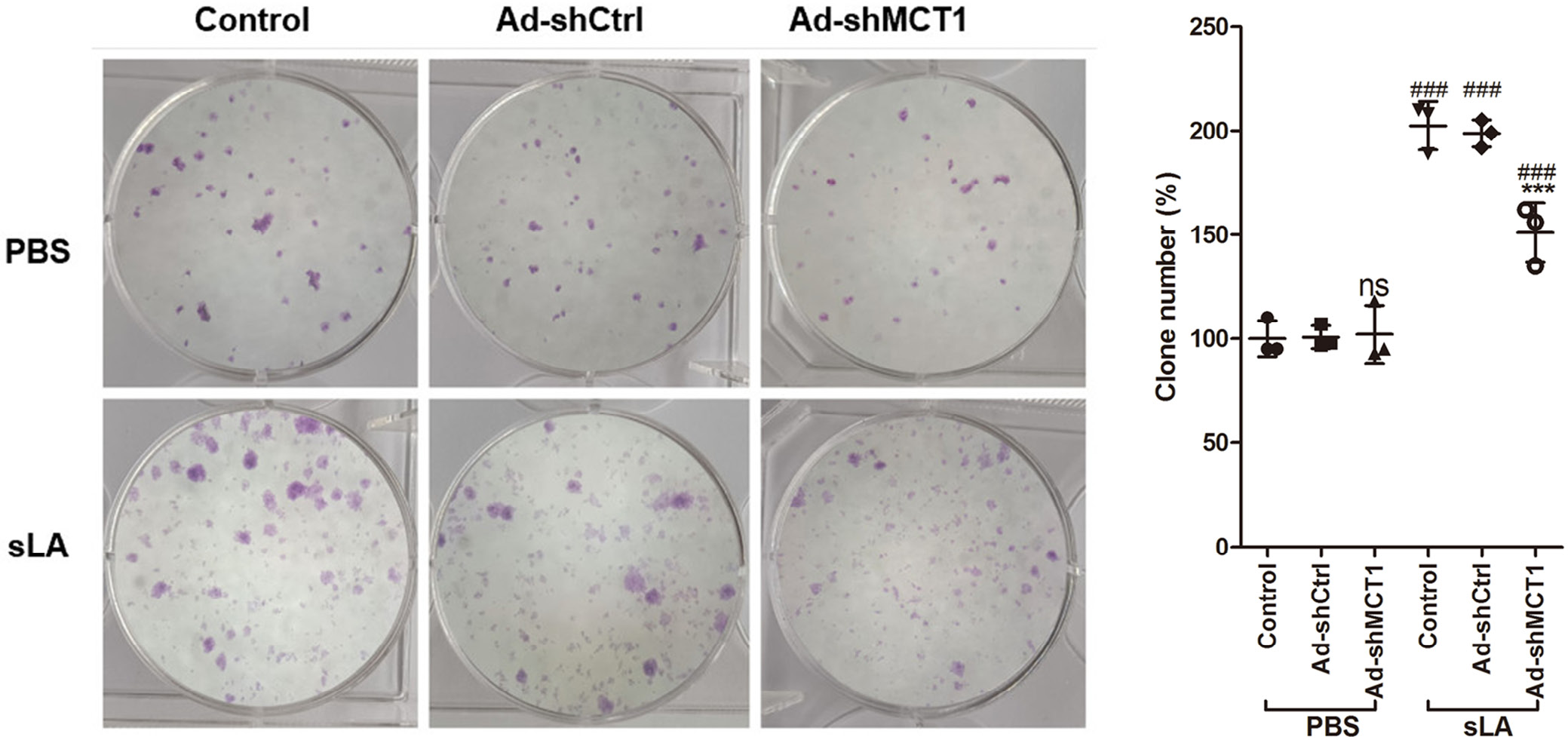

Cell clone formation test

The DC-induced CTLs and U14 cells were mixed and cultured (1:10), and after 24 h of culture, they were digested with trypsin. The cells were resuspended as a single-cell suspension, and 1000 cells were seeded into a 6-centimeter culture dish and incubated in a culture medium at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 14 days. Then, the cells were stained with crystal violet and the number of clones was counted.

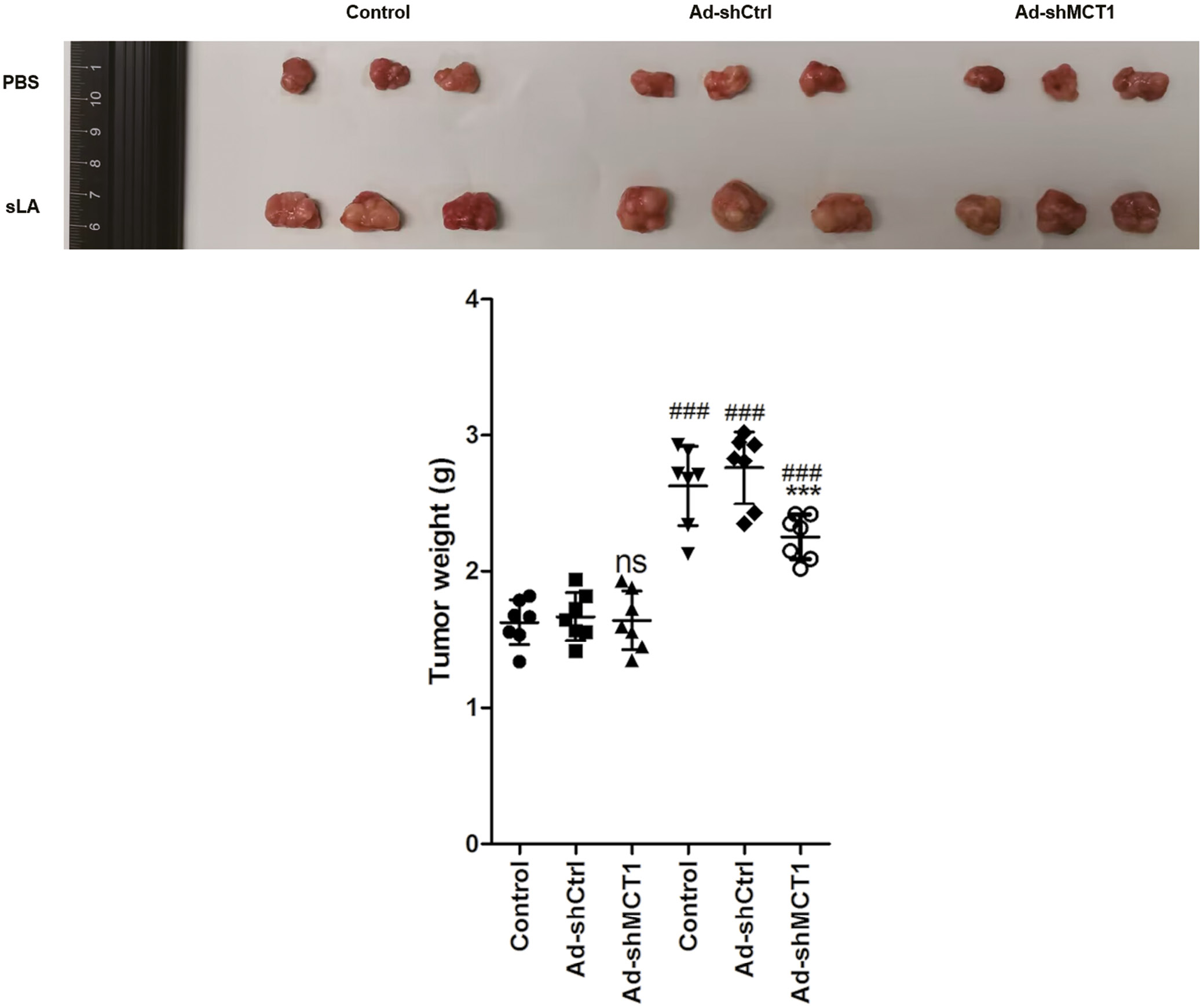

Nude mouse U14 cell xenograft

After a week of adaptive feeding, 42 nude mice (6–8 weeks old, 18–22 g) were randomly divided into 6 groups. The U14 cells in the ratio of 2×106 cells/100 μL were injected subcutaneously into the back of the mice. After 10 days, 2×106 cells/200 μL of DC-induced CTLs were injected into U14 xenografts for treatment once a week for a period of 30 days. Subsequently, mice were euthanized, and the U14 xenografts were isolated and compared for tumor tissue weight.

Statistical analyses

The SPSS v. 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) and GraphPad Prism (v. 5.0; GraphPad Software, Boston, USA) were used to analyze data. The measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. We used the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess whether the measured data conform to the normal distribution in SPSS. The p-value was calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test between multiple groups in GraphPad Prism. Student’s t-test was used to compare the differences between 2 groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

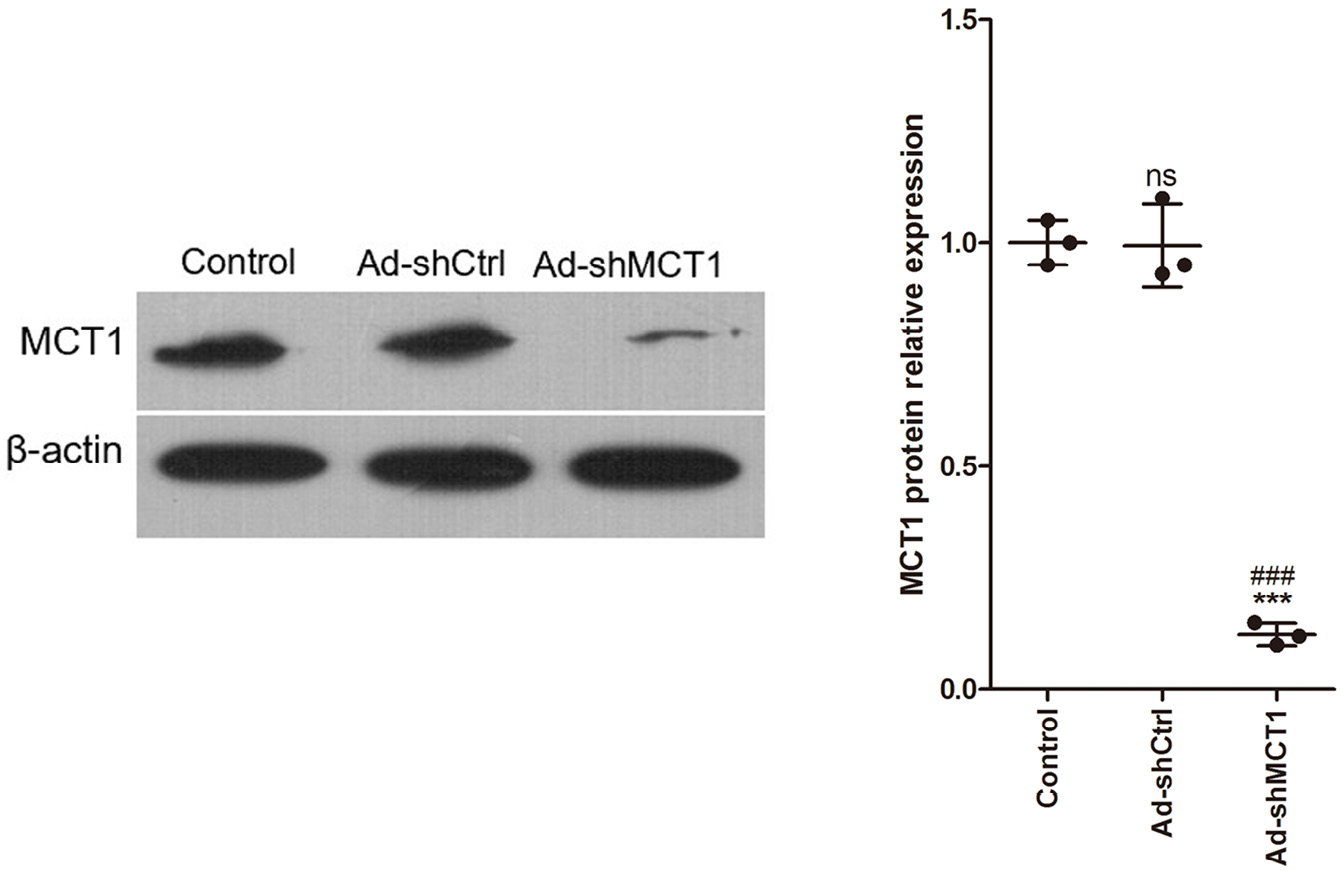

Analysis of silencing MCT1 in DCs

Immunoblotting was used to detect the expression of MCT1 protein in DCs in order to analyze the MCT1 gene silencing effect of Ad-shMCT1 adenovirus. Results showed that Ad-shMCT1 adenovirus significantly decreased the expression of MCT1 protein in DCs compared to the control group (p < 0.05, honestly significant difference (HSD) test following ANOVA, Figure 1 and Table 1).

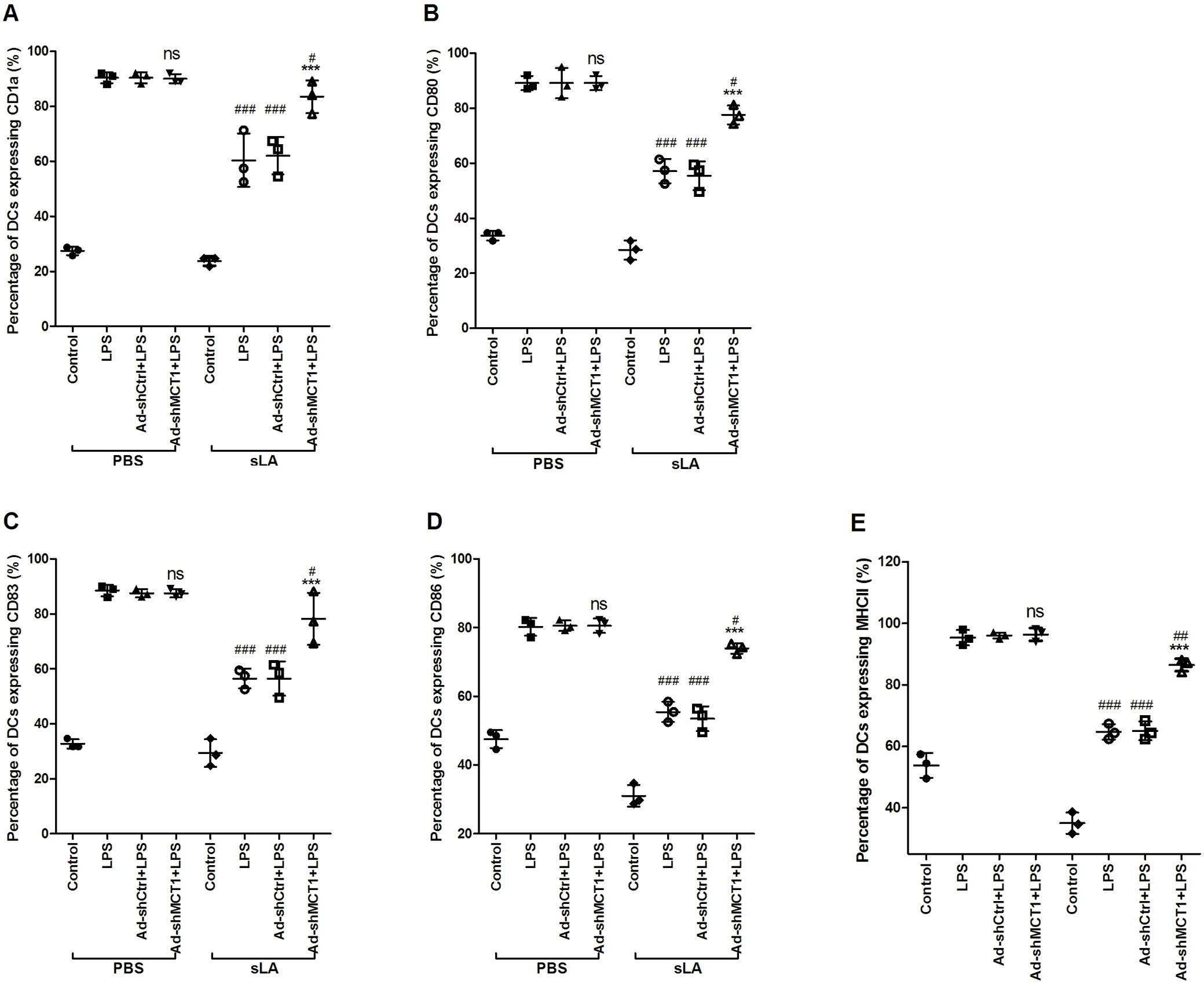

MCT1 silencing alters the phenotype of mature DCs following sLA exposure

In the absence of sLA, MCT1 silencing did not affect the percentage of DCs expressing CD1a, CD80, CD83, CD86, and MHCII. Upon sLA exposure and MCT1 silencing, the percentage of DCs significantly increased (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA, Figure 2 and Table 2). However, after sLA exposure and LPS stimulation, the rate of DCs significantly decreased, without a concomitant change in DC viability (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

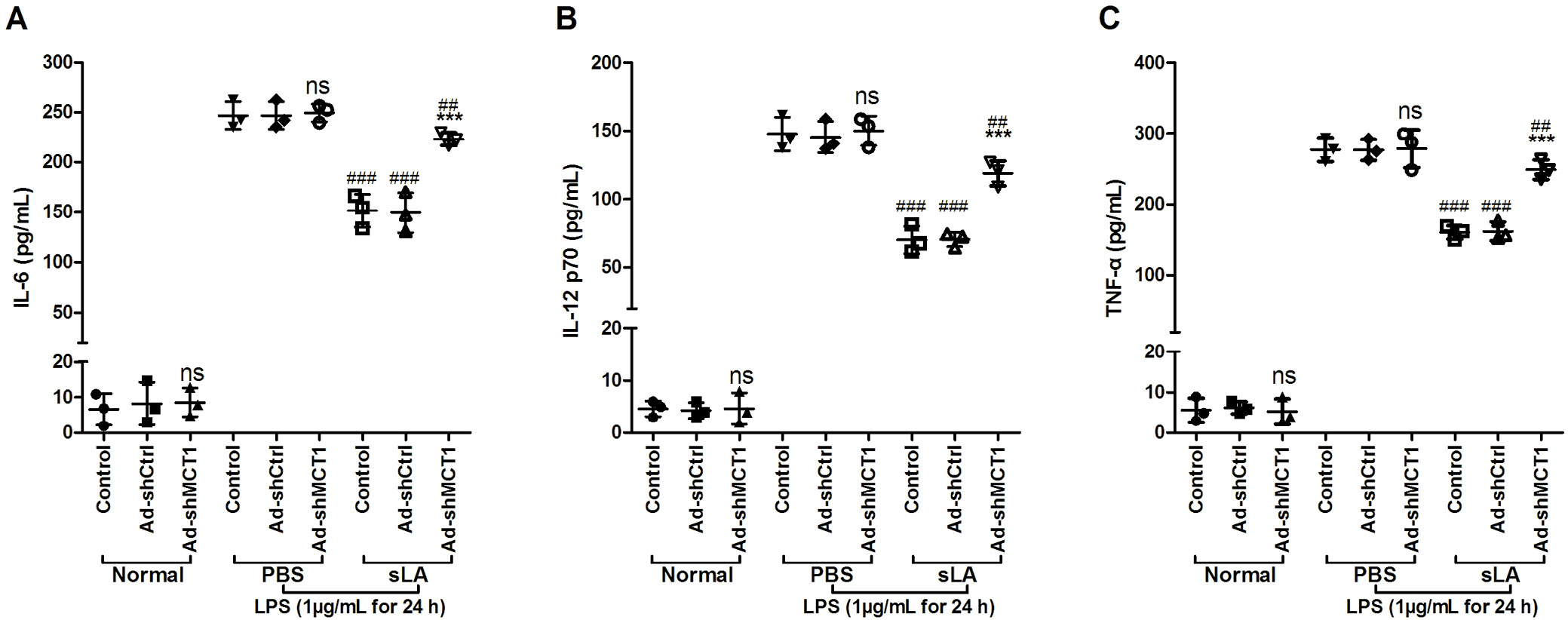

MCT1 silencing alters the secretion of cytokine from DCs after sLA exposure

The MCT1 silencing significantly increased the DC levels of IL-6, IL-12 p70 and TNF-α after sLA exposure (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA, Figure 3 and Table 3). In the absence of sLA exposure, MCT1 silencing did not affect the secretion of IL-6, IL-12 p70 and TNF-α from DCs. However, the exposure of DCs to sLA and LPS decreased the levels of these cytokines.

Impact of MCT1 gene silencing on the immune effect of DCs

To analyze the toxicity effect of DC-induced CTLs on cervical cancer cells, we generated CTLs (defined as DC-induced CTLs) by co-culturing DCs and T cells for 1 week, and then co-culturing the obtained CTLs with U14 cells. In DC-induced CTLs without sLA exposure, the lysis rate of U14 cells was independent of whether MCT1 was silenced (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA, Figure 4 and Table 4). However, DC-induced CTLs with sLA exposure and MCT1 silencing significantly increased the lysis rate of U14 cells (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA testing, Figure 4 and Table 4). Simultaneously, in a DC-induced CTL and U14 cell co-culture system, the MCT1 silencing without sLA exposure did not affect the number of U14 clones, but it decreased the U14 cell clone number (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA testing, Figure 5 and Table 5). Consistently, in vivo, MCT1 silencing without sLA exposure did not affect the weight of U14 xenograft, while xenografts demonstrated significantly decreased weight with MCT1 silencing and sLA exposure (p < 0.05, HSD test following ANOVA testing, Figure 6 and Table 6).

Discussion

For decades, lactate was considered a metabolic waste product. However, in recent years, it has been reported that the output of lactic acid from the glycolysis of tumor cells can promote the proliferation of tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, it aids in immune tolerance and helps tumor cells escape detection by immune cells.21, 22, 23 The Warburg Effect of cancer cells makes them more inclined to use glycolysis for energy, and the accompanying lactic acid is a product of their metabolism. Importantly, lactate exported by cancer cells into the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor cell proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis, and immune tolerance.9, 10 It has been reported that lactate is a potent inhibitor of T cell and NK cell survival and function, modulating the phenotype of DCs and macrophages.11, 12, 13 A recent study reported that AZD3965, an MCT1 inhibitor, could reverse the immunosuppressive micro-environment of solid tumors, thereby improving the safety and anti-tumor efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.24 Hence, the inhibition of MCT1 can be viewed as a new strategy for tumor immunotherapy.

In this study, we silenced the MCT1 expression in BM-derived DCs by adenovirus infection and found that MCT1 silencing affected the phenotype and cytokine secretion of BM-derived DCs, although only when also exposed to sLA. Specifically, MCT1 silencing upregulated the expression of CD1a, CD80, CD83, CD86, and MHCII, and the secretion of IL-6, IL-12 p70 and TNF-α in BM-derived DCs after sLA exposure and LPS challenge. The MCT1 is a member of the monocarboxylate transporter family, which plays an essential regulatory role in glycolysis by mediating the transmembrane transport of lactate.25, 26 It has been reported that MCT1 is upregulated in cervical cancer tissues and contributes to disease progression by promoting the proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of cervical cancer cells. Its mechanism is thought to be related to the regulation of lactate metabolism in the tumor microenvironment.27, 28, 29

Furthermore, lactate that is accumulated in the tumor microenvironment is transported from extracellular to intracellular microenvironment via MCT1 to regulate its phenotypic changes, ultimately resulting in immunosuppression.13, 18 This is considered an essential measure of immune evasion of tumor cells. Sangsuwan et al. revealed that lactate exposure reduces the expression of CD11c, CD80, CD86, and MCHII, and results in a decreased secretion of IL-12 in DCs, which is consistent with the results of the present study.13 More importantly, our study found that silencing MCT1 attenuated these changes induced by lactate exposure in DCs, providing a new strategy for tumor immunotherapy.

A robust immune response against tumors depends on several factors, such as the degree of maturation and activation of DCs, their ability to capture, process and present exogenous antigens, as well as their transport to secondary lymphoid organs and the tissue types from which they arise.30, 31 Dendritic cells are critical for initiating anti-tumor immunity, as they activate various immune cells, including T cells, to establish anti-tumor resistant barriers. In this study, we demonstrated that we could induce CTLs by co-culturing DCs and splenic T cells. Our findings showed that CTLs derived from sLA-exposed DCs were less effective against U14 cells than those derived from DCs not exposed to sLA. However, MCT1 silencing significantly increased the toxicity of sLA-exposed DC-derived CTLs to U14 cells both in vivo and in vitro. The results suggest that lactate exposure reduced the antigen-presenting capacity of DCs, but MCT1 silencing could attenuate the effects of lactate exposure. Under physiological conditions, DCs often exhibit an immature phenotype in vivo, characterized by low surface levels of MHCII and costimulatory molecules, and induce suboptimal T cell priming, often resulting in T cell anergy or tolerance.32, 33, 34 Dendritic cells matured and activated by antigens were found to highly express MHCII and costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD83 and CD86), which induced potent T cell activation and effector differentiation.35, 36 However, lactate-mediated signaling has been shown to hinder the maturation, activation and antigen presentation of DCs, resulting in widespread immunosuppression.37 The MCT1 is a crucial protein involved in the signaling pathways of lactate in DCs, and conversely, lactate has been shown to regulate the expression of MCT1. Therefore, silencing of MCT1 could theoretically attenuate the functional and phenotypic changes of DCs induced by lactate exposure. Our findings provide evidence to support this hypothesis.

Limitations

The present study demonstrated that MCT1 gene silencing attenuated lactate exposure and decreased dendritic cell immunity against cervical cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. However, this study did not further investigate the specific molecular mechanism of the changes caused by MCT1 silencing.

Conclusions

Lactate exposure reduces the immunological effect of DCs on cervical cancer cells. However, this effect can be mitigated by MCT1 gene silencing, thereby reducing the impact of lactate exposure on DCs.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281170. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Statistics for Figure 1.

Supplementary Table 2. Statistics for Figure 2.

Supplementary Table 3. Statistics for Figure 3.

Supplementary Table 4. Statistics for Figure 4.

Supplementary Table 5. Statistics for Figure 5.

Supplementary Table 6. Statistics for Figure 6.

Supplementary Table 7. Statistics for Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Cube maps for the levels of DC marker expression after sLA exposure and LPS challenge. Dendritic cells were first infected with Ad-shCtrl and Ad-shMCT1 adenoviruses for 24 h, then co-cultured with 50 mM of sLA or PBS for 48 h, and finally stimulated with 1 µg/mL LPS for 24 h. Flow cytometry was used to detect the expression of CD1a (A), CD80 (B), CD83 (C), CD86 (D), and MHCII (E) in DCs. The column height represents the average value, and the bar of the column is the standard deviation. The p-value was calculated by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test following analysis of variance (ANOVA) between multiple groups or by Student’s t-test (PBS compared to sLA treatment).