Abstract

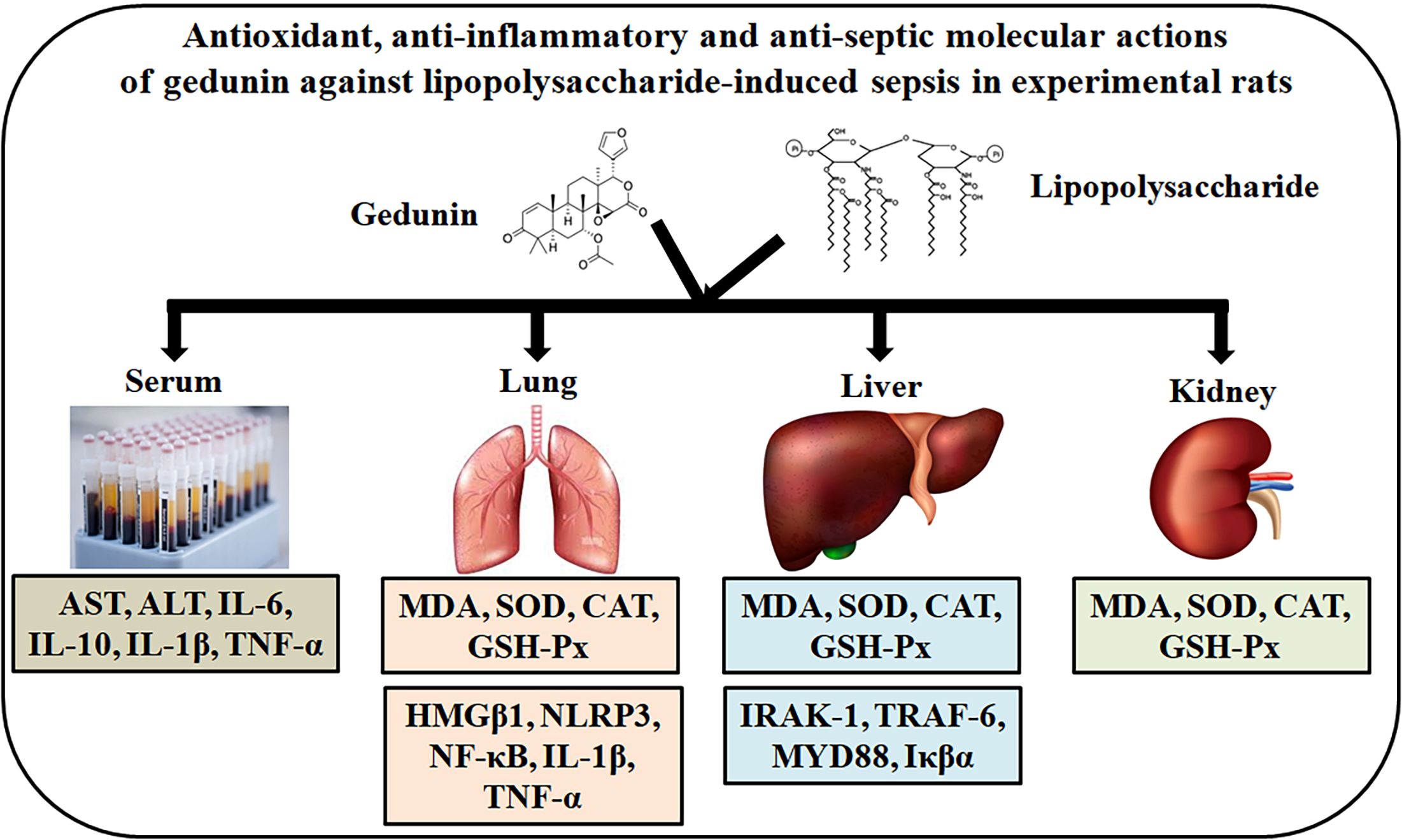

Background. Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction without effective therapeutic options. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial endotoxin, is known to induce sepsis. It is associated with oxidative stress, inflammation and multiple organ failure. Gedunin (GN) is a tetranortriterpenoid isolated from the Meliaceae family. Gedunin possesses numerous pharmacological properties, including antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiallergic, and anticancer activities. However, the molecular anti-inflammatory mechanism of GN in sepsis has not been established.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to explore the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory molecular actions underlying the antiseptic activity of GN in an LPS-induced rat model.

Materials and methods. Rats were randomized into 4 sets: group 1 (control) was given 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) by gavage, group 2 rats were treated with LPS (100 μg/kg body weight (BW), intraperitoneally (ip.)), group 3 rats were given LPS (100 μg/kg BW, ip.)+GN (50 mg/kg BW in DMSO), and rats in the group 4 were given GN (50 mg/kg BW in DMSO) alone. We studied hepatic markers, inflammatory cytokines and antioxidants using specific biochemical kits and analyzed their statistical significance. Histopathology of liver, lungs and kidney tissues was also explored. The mRNA levels and conducted protein investigations were performed using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and western blot, respectively.

Results. Our findings revealed that GN significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited oxidative stress, lipid peroxides, toxic markers, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and histological changes, thereby preventing multi-organ impairment. Additionally, GN attenuated the HMGβ1/NLRP3/NF-κB signaling pathway and prevented the degradation of Iκβα.

Conclusions. Gedunin is a promising natural antiseptic agent for LPS-induced sepsis in rats.

Key words: oxidative stress, sepsis, lipopolysaccharide, gedunin, HMGβ1/NLRP3/NF-κB pathway

Background

Sepsis is triggered by microorganisms or microbial toxins, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Lipopolysaccharide, an endotoxin of Gram-negative bacteria, causes a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).1, 2 In the USA, 700,000 sepsis cases with more than 200,000 deaths occur annually and the condition contributes to 10% of deaths.3 Sepsis is the invasion of microbes or endotoxins into cells and body fluids and it activates the inflammatory pathways.4 The healing process is initiated by an inflammatory response. However, high doses of endotoxin cause imbalances in reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammatory cytokines and homeostasis, which lead to organ dysfunction.5 Lipopolysaccharide triggers the discharge of strong pro-inflammatory intermediaries, causing cardiac disorders, multiple organ disorders, tremors, and death.6, 7 Sepsis induces a drop in general vascular function, leading to multiple organ failure.8 Almost half of the patients with septic shock develop acute renal failure (ARF) and require dialysis.9 Sepsis leads to hemodynamic fluctuations such as hypotension, drop in renal blood flow, and local renal ischemia causing ARF.10 Moreover, the condition causes tissue impairment, multiple organ dysfunction, acute lung disease, septic shock, and death.11, 12 Due to its critical nature, sepsis attracts the attention of clinicians and researchers. Thus, both in-vitro and in-vivo experiments are being conducted to find new antiseptic agents.13

An endotoxin, LPS, has been used to prompt sepsis in the experimental rat model.14 Lipopolysaccharide activates the inflammatory cascade by stimulating macrophage and monocyte cell membrane receptors. This triggers nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathways, which in turn stimulate the discharge of cytokines, pro-inflammatory intermediaries and ROS from leukocytes, plasma and blood cells.15 The key cytokines, namely interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6, are significant controllers in the inflammatory reaction during sepsis. The TNF-α is a primary mediator of septic shock. It is released instantly after infection and causes the pathological progression of septic shock. In reaction to cytokines, ROS are produced from neutrophils and phagocytic cells, which trigger oxidative stress.16 The free radicals produce malondialdehyde (MDA) and impair biomolecules. This leads to various chronic illnesses, namely osteoporosis, atherosclerosis, cancer, and arthritis.15, 17 Unrestrained inflammation and extreme oxidative stress are the prominent signs of sepsis that culminate in multiple organ failures and mortality.18 Due to an excess of free radicals, oxidative stress is rummaged by antioxidant guard systems, including catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px).19 Hence, sepsis can be treated with antibiotics, antioxidants, corticosteroids, and anti-inflammatory mediators.

Oxidative stress is crucial in sepsis-associated transience and multi-organ impairment.16, 18 Many researchers have been attentive to anti-cytokines, drug targets and antioxidants to control the pathophysiology of sepsis-prompted acute lung injury (ALI).13, 19 The high mobility group box (HMGβ1) protein plays a vital part in the development and evolution of sepsis-prompted lung damage.20 The HMGβ1 is stimulated by immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells and mononuclear cells, and induced by inflammatory cytokines and endotoxins.21 Hence, the restraint of HMGβ1 discharge mitigates SIRS and sepsis-induced organ injury.22 A previous study on the activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of pro-IL-β also highlighted the key role of NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes in inflammation.23 Increased NLRP3 expression causes the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune cell gathering, and augmented stimulation of the adaptive immune reaction.23, 24 Hou et al.25 described that NLRP3 facilitated the increased secretion of HMGβ1 in lung injury. Thus, drugs targeting the inhibition of HMGβ1 and NLPR3 have a possible role in the treatment of sepsis and associated lung failure. Potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities might reduce the severity of sepsis. Isik et al.26 demonstrated that sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the accepted approach to stage the clinically negative axilla, and the incidence of lymphedema (LE) after SLNB is about 5%. Furthermore, the authors hypothesized that patients undergoing axillary excision of >5 lymph nodes (LNs) were at an increased risk of developing LE.

Gedunin (GN) is the main tetranortriterpenoid sequestered from the neem tree. Gedunin is identified to restrain the stress-prompted chaperone heat shock protein, Hsp90.27 Blocking Hsp90 produces a multi-directed beneficial method since Hsp90 proteins are associated with numerous transcription factors and kinases, particularly NF-κB.28 The Hsp90 regulators diminish inflammation in various experimental models, such as atherosclerosis, uveitis and lung inflammation.29, 30 Gedunin can restrain prostate gland, ovary and colon cancer cell proliferation.31, 32 It also subdues articular inflammation in a zymosan-induced acute articular inflammation model.33 Gedunin affixes to MD-2, damages TLR4/MD-2/CD14 pathways, and reduces LPS-stimulated inflammatory reactions in macrophages in silico and surface plasmon resonance studies.34 However, the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and in-vivo antiseptic efficacy of GN in LPS-induced sepsis has not yet been evaluated.

Objectives

Hence, the current research explores the molecular actions underlying the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiseptic activity of GN in the LPS-induced rat model.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Gedunin, LPS, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), antibodies, antibiotics, and all the biochemicals were obtained from Gibco (Carlsbad, USA). The antibodies for western blot analysis were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA).

Trial animals

A total of 40 Wistar albino male rats weighing 225–250 g were obtained from Xi’an Yifengda Biotechnology Co., Ltd (XI’an, China). Rats were housed in aseptic polypropylene cages under fixed laboratory circumstances. The animals were nourished with a regular pellet diet ad libitum. Rats were adapted for 7 days before the experiments. The trial was approved by the of Xi’an Zhongkai Animal Experiments Medical Research Ethics Committee (approval No. 4894).

Experimental design

The animals were randomized into 4 sets of 10 rats each. Group 1 was the control group and was given 1 mL of DMSO for 10 days by gavage. The rats in the group 2 were given a single dosage of LPS (100 μg/kg body weight (BW), intraperitoneally (ip.)). Group 3 rats were administered LPS (100 μg/kg b.w., i.p.)+GN (50 mg/kg b.w. in DMSO). The rats in the group 4 were treated with GN (50 mg/kg b.w. in DMSO) alone. A single intraperitoneal dose of LPS was injected, and 1 mL of GN was given daily for 10 days by alimentation. After the experiment, all animals were anesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Sample preparation

The blood of the rats was drawn through cardiac puncture and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm. The serum was separated and preserved at −80°C. The residual serum was recollected at 4°C to estimate hepatic markers. Tissues (liver, kidney and lung) were dissected and divided into 2 parts. One portion was kept at −80°C for antioxidant assessments. The second part of the tissues was fixed in 10% formalin for histopathological assessment.35

Biochemical assessments

For biochemical analyses, tissues of the rats’ liver, kidney and lung were washed with deionized ice-cold water. One gram of tissue sample was treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH: 7.2, 1:9 ratio) and was homogenized. Afterward, the homogenate was centrifuged for 1 h, and the supernatant was analyzed. Malondialdehyde, CAT, SOD, and GSH-Px were determined by the kits acquired from Elabscience (Wuhan, China). Cytokine levels were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Toxicity markers (aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT)) were assayed using kits delivered by Cayman Chemical, according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Histopathological analysis

Liver, kidney and lung tissues were preserved with formaldehyde (10%), fixed in paraffin blocks, cut into slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Successively, stained tissues were identified for histological changes and inflammation under a light microscope (model CX33; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Determination of mRNA levels by qRT-PCR

The total RNA of lung tissue was sequestered using TRIzol® reagent (Abcam, Waltham, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The isolated RNA was converted to cDNA through reverse transcription by using a high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology). FastStart SYBR Green Master Mix (Abcam) was used to explore the cDNAs. The band intensity was scrutinized with 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Finally, the band intensity was measured by Image J v. 1.48 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA). The fold variations were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt formula. The used real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) primer sequences are as follows (Table 1):

Western blotting analysis

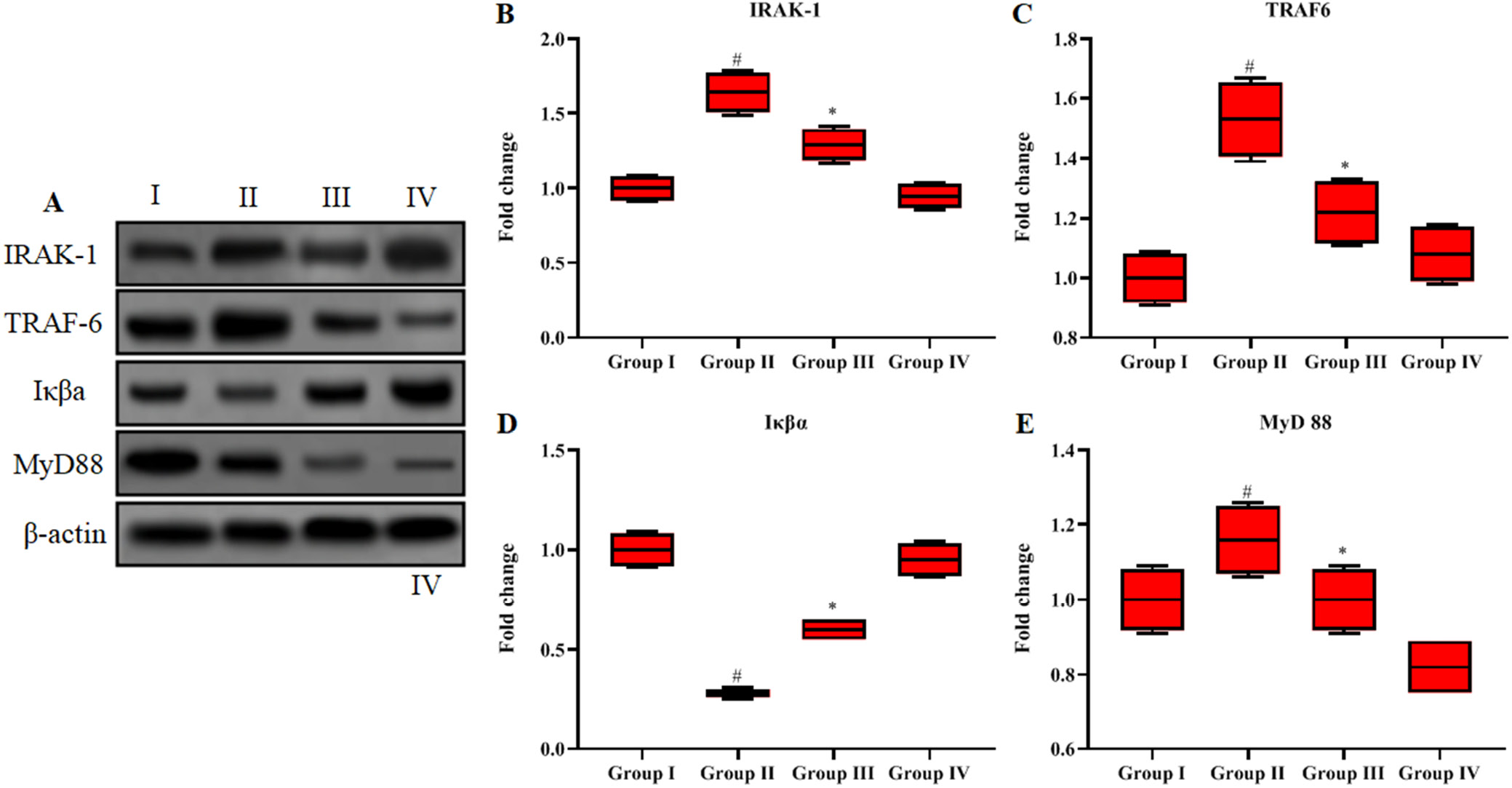

Hepatic tissue was dissected 12 h after the induction of sepsis.33 The tissues were cleaned twice with PBS and lysed with a cold lysis buffer consisting of 0.01% protease inhibitor. Then, these were preserved on ice for half an hour. The lysate was cold (4°C) and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm, and the resulting solution was passed through sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10%) and shifted electrophoretically to the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) film. Then, 5% of fat-free milk was used to block the membrane. Next, it was conserved with the primary antibodies, namely IRAK-1 (sc-5288), TRAF-6 (sc-8409), Iκβα (sc-1643), MyD88 (sc-74532), and β-actin (sc-69879), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution). The β-actin was utilized as a reference. The membrane was reviewed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Millipore, Burlington, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v. 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) and SPSS v. 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) software. The measurement data were reported as median and quartiles. The normality of the distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All parameters had normal distribution for which we used a nonparametric test due to small sample sizes. The comparison among groups was performed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s test to compare variables among the groups. When the test standard had a value of p < 0.05, the difference was considered statistically significant.

Results

All variables had a normal distribution. Table 2 demonstrates the results of compared variables among the groups.

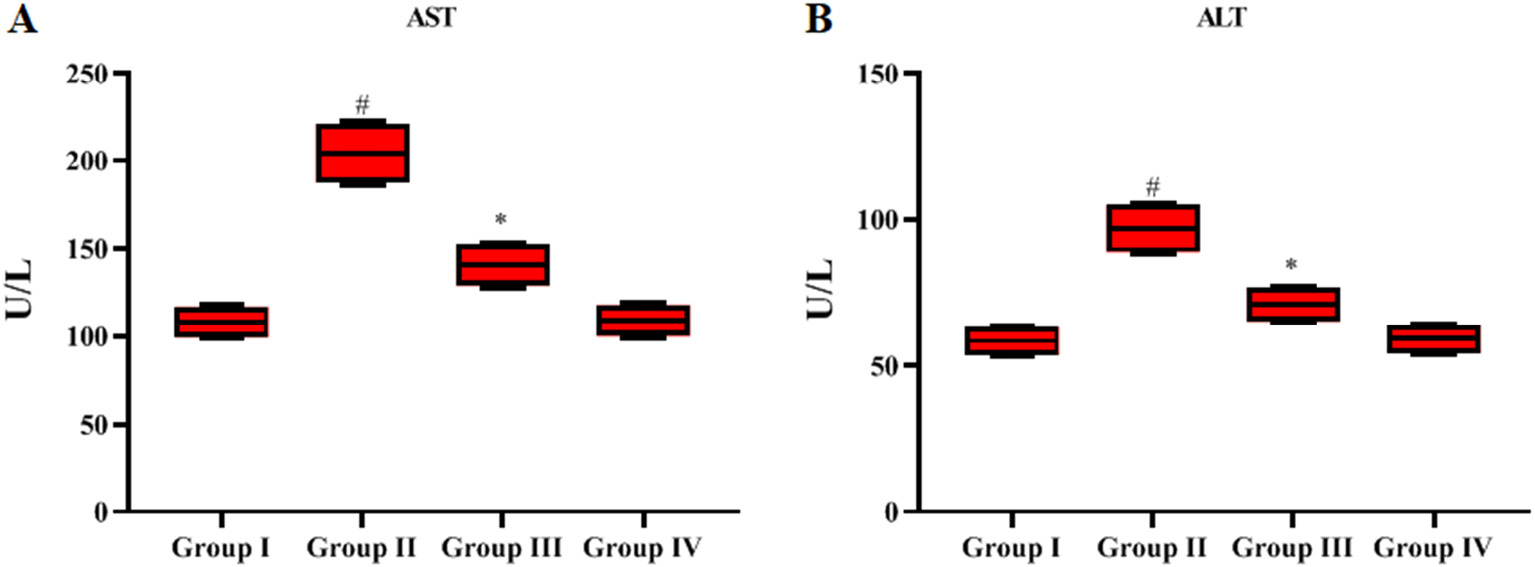

GN reduces hepatic toxicity enzyme markers

Hepatic toxicity serum enzymes (AST and ALT) were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) in LPS-treated septic rats compared to controls (Figure 1A,B). The hepatic enzyme levels were reduced in the LPS-treated GN group. Normal marker enzyme levels were detected in the GN alone-treated rats and control rats. Hence, GN may be effective in reducing liver damage.

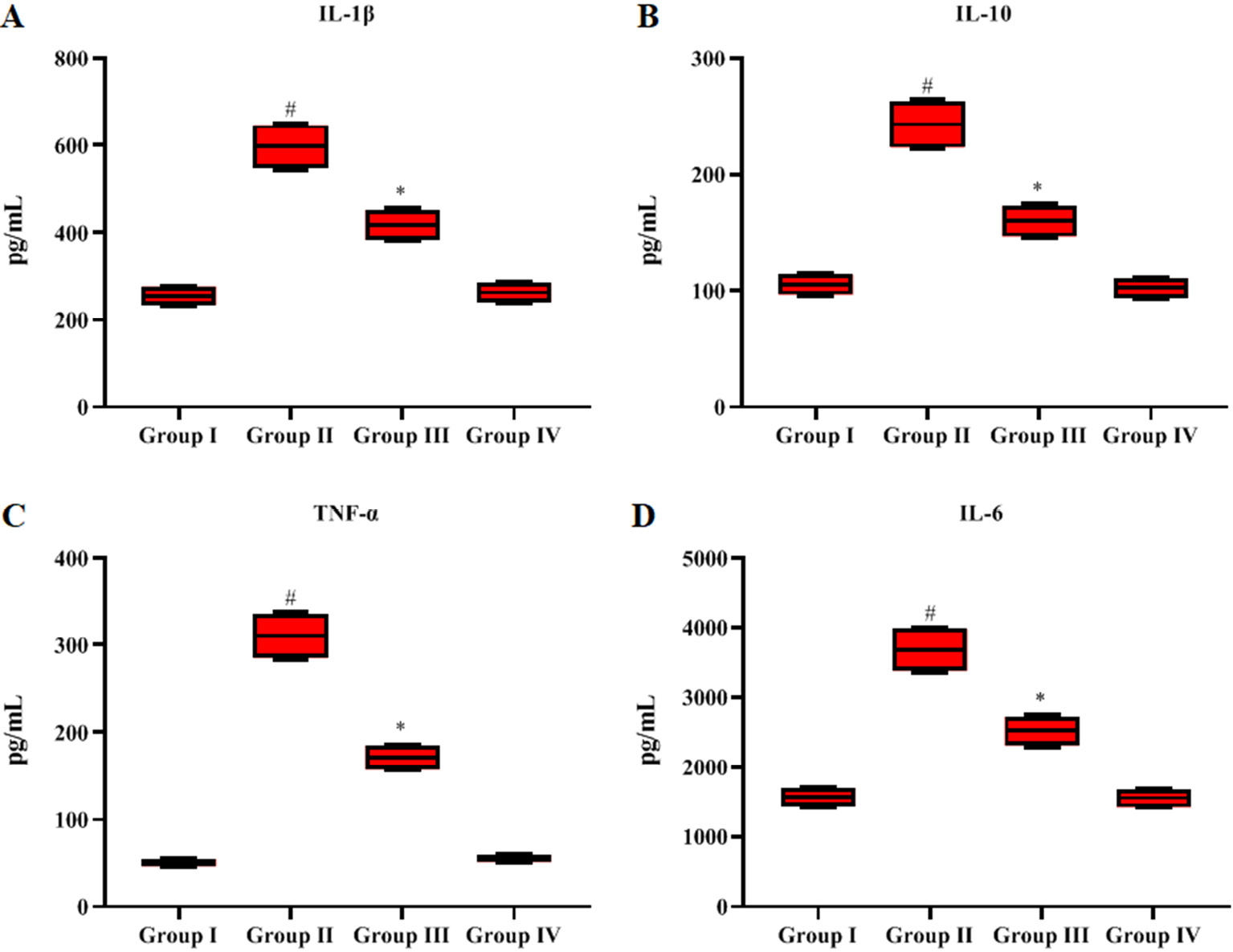

GN alleviates pro-inflammatory cytokine levels

The serum cytokines, namely IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, and TNF-α, were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) in LPS-induced sepsis animals (Figure 2A–D). The cytokine levels declined in the GN+LPS-prompted septic rats. Cytokine levels in control rats and GN alone-treated rats were similar.

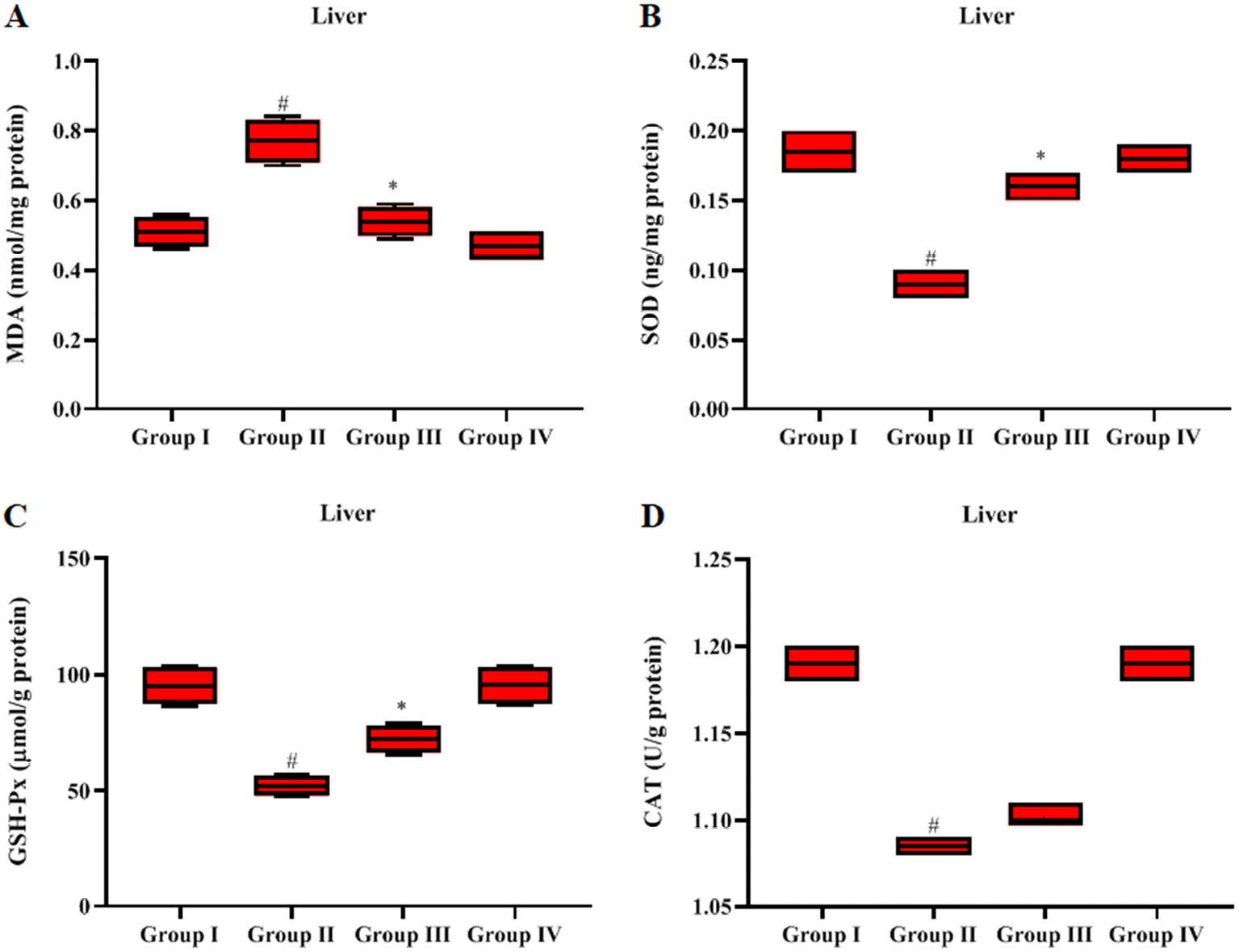

Effect of GN on MDA and antioxidant enzymes in hepatic tissue

Malondialdehyde levels in liver tissue were significantly higher (p < 0.05), and antioxidant enzyme (SOD, CAT and GSH-Px) levels were lower in the LPS-induced sepsis animals compared to the control rats (Figure 3A–D). The GN+LPS-treated rats had significantly decreased (p < 0.05) MDA levels and increased antioxidant enzymes compared to the LPS alone-treated rats. The GN alone-treated rats had similar results to the control rats.

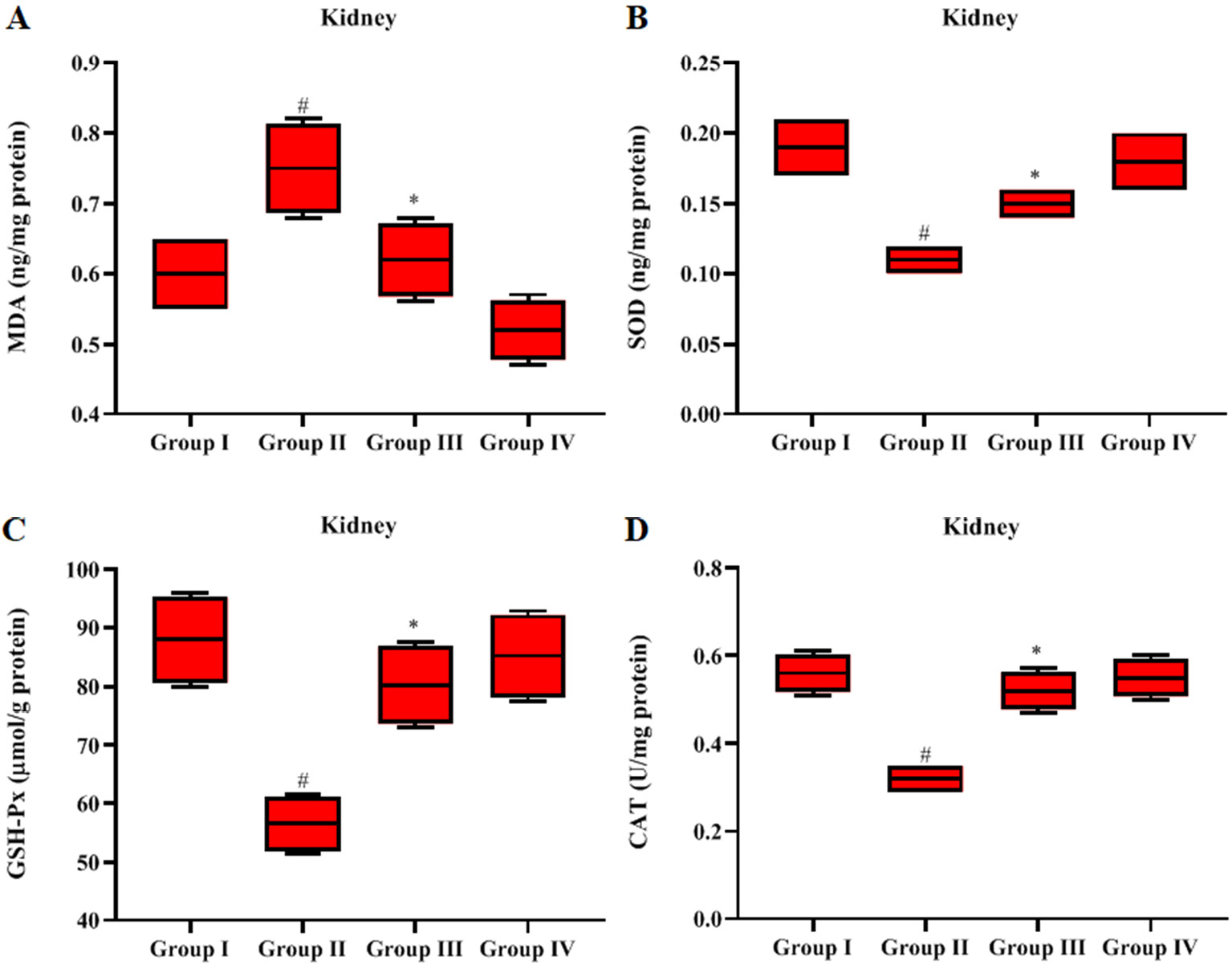

Effect of GN on MDA and antioxidant enzymes in kidney tissue

Malondialdehyde levels were significantly increased in kidney tissues (p < 0.05), and antioxidant enzyme (SOD, CAT and GSH-Px) levels were alleviated in the LPS-induced septic rats compared to the controls (Figure 4A–D). The GN+LPS-treated rats had significantly reduced (p < 0.05) MDA levels and enhanced antioxidant enzymes in comparison to the LPS alone-treated rats. The GN alone-treated rats displayed similar results as controls.

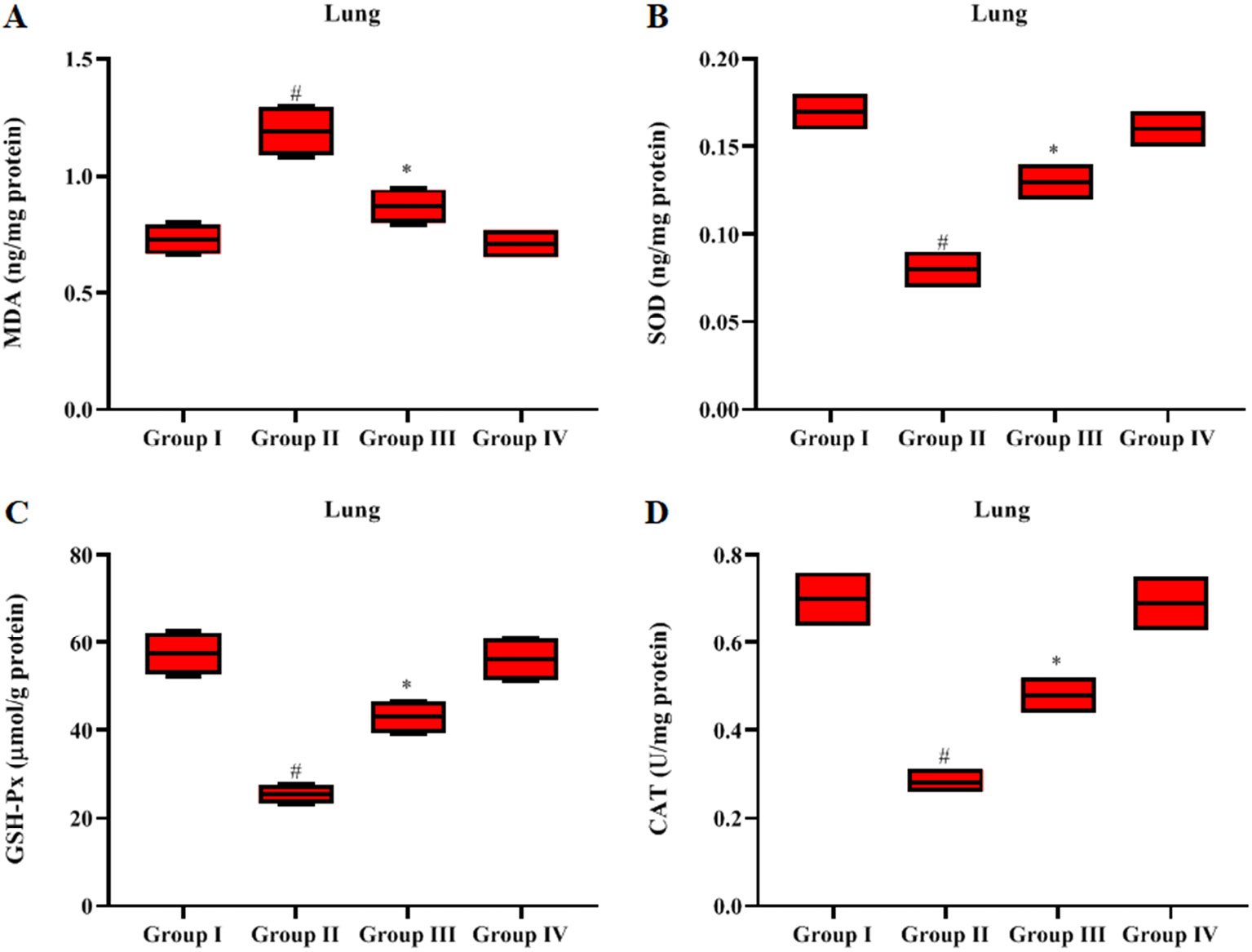

Effect of GN on MDA and antioxidant enzymes in lung tissue

Malondialdehyde levels in lung tissues were significantly increased (p < 0.05), and antioxidant enzyme (SOD, CAT and GSH-Px) levels were reduced in the LPS-induced septic rats in contrast to the control rats (Figure 5A–D). The GN+LPS-treated rats had significantly reduced (p < 0.05) MDA levels and augmented antioxidant enzymes as compared to the LPS alone-treated rats. The GN alone-treated rats presented similar results as controls.

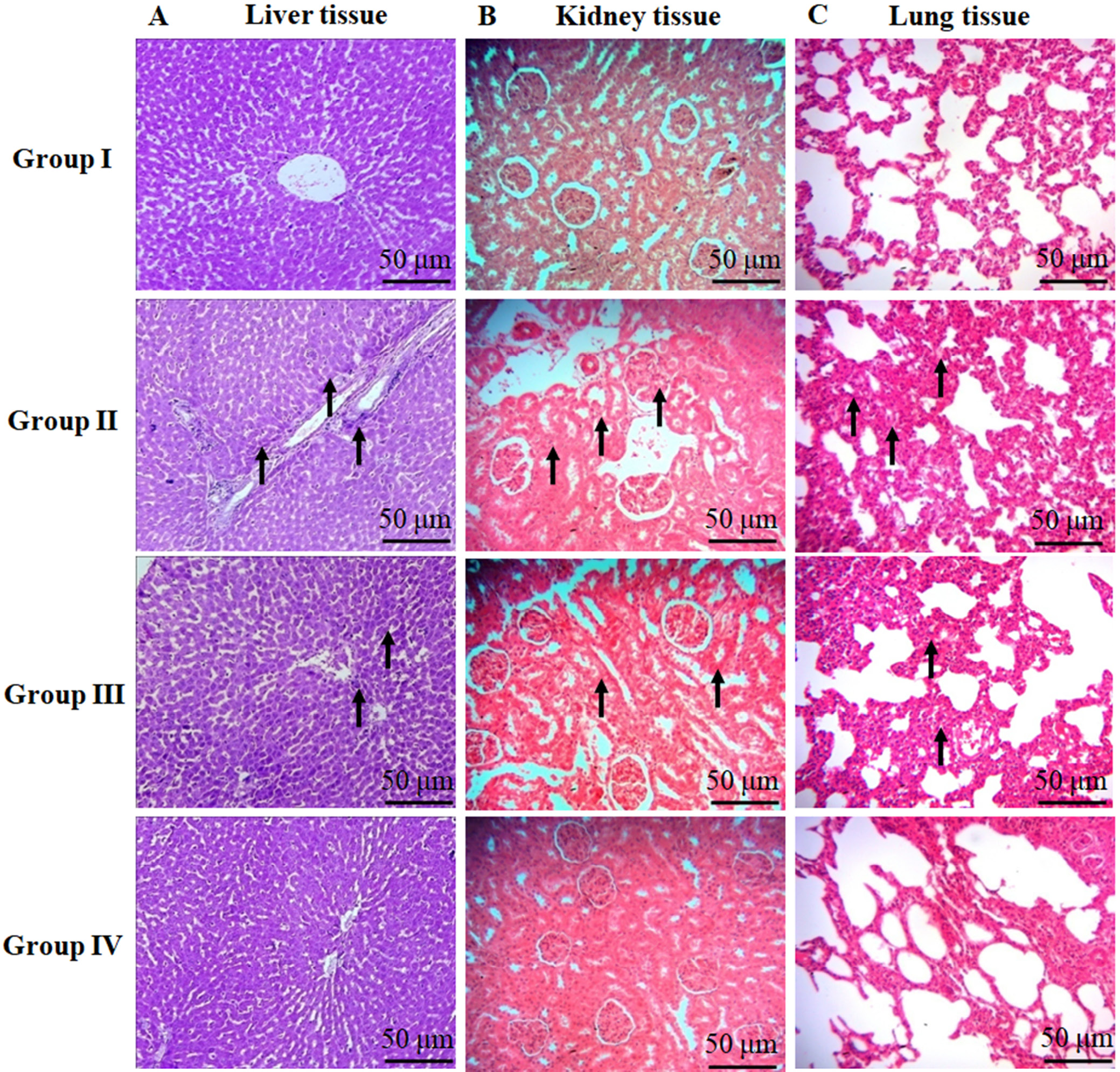

Effect of GN on histopathological analysis of liver, kidney and lung tissues

Figure 6A–C exhibit the histopathological examination of the liver, kidneys and lungs in control and experimental rats. Histopathological damages and lesions were absent in the hepatic, kidney and lung tissues of control and GN alone-treated rats. Lipopolysaccharide caused severe inflammation and damage to hepatic tissues, as well as inter-alveolar septum condensing, hyperemia, and severe inflammation in the peri-bronchiolar and peri-vascular regions of the lungs. Moreover, it induced modest assembly of the hyaline cylinder in the lumen of renal tubules, mild relapse of tubular epithelium, and serious interstitial vessel hyperemia in renal tissues. The GN-treated septic rats demonstrated mild renal tubule lumens and extinct deterioration in the tubular hyperemia in comparison to the LPS-prompted septic rats. Only mild inflammation of hepatic tissue was present in the GN-supplemented septic rats. The GN group presented with condensed interstitial thickening and inflammation in the lungs in contrast to the LPS-stimulated sepsis animals.

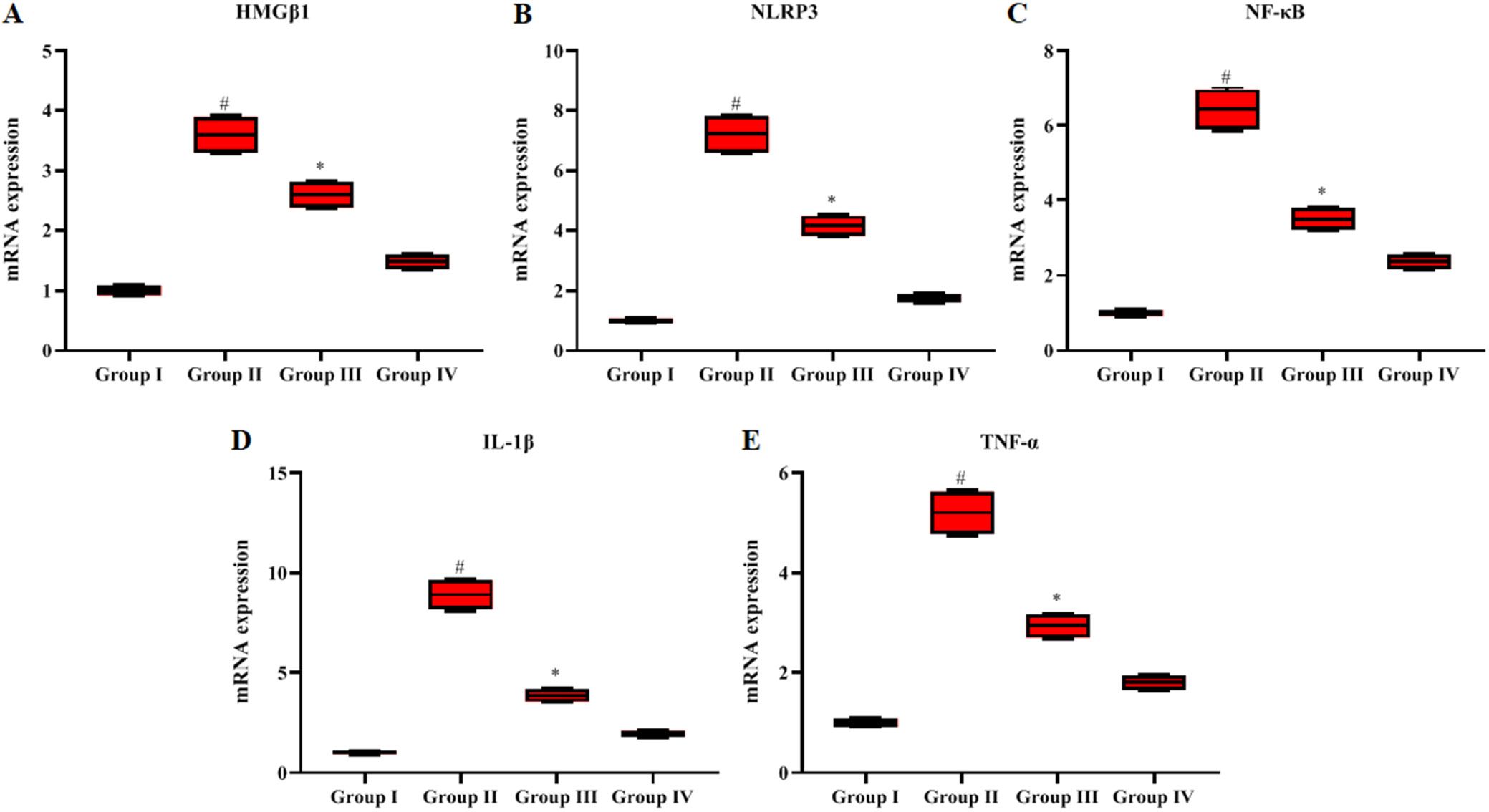

GN alleviates mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators in lung tissues of LPS-induced septic rats

To assess whether GN (50 mg/kg BW) mitigated inflammation in lung tissues of septic rats, the HMGβ1, NF-κB, NLRP3, TNF-α, and IL-1β mRNA levels were evaluated (Figure 7A–E). The levels of HMGβ1, NF-κB, NLRP3, TNF-α, and IL-1β mRNA were significantly enhanced (p < 0.05) in the LPS-induced septic rats as compared to the control group. The administration of GN significantly attenuated (p < 0.05) these inflammatory mediators in contrast to the LPS-prompted septic rats (Figure 7).

GN attenuates the protein expression of IRAK-1, TRAF-6, MYD88, and Iκβα in hepatic tissues of LPS-induced septic rats

In the western blot analysis, we found that the protein levels of IRAK-1, TRAF-6 and MYD88 were augmented, whereas Iκβα levels declined in the hepatic tissues of LPS-prompted sepsis animals (Figure 8A–E). It was observed that GN reduced IRAK-1, TRAF-6 and MyD88 levels, and enhanced Iκβα protein levels in hepatic tissues. The stimulation of NF-κB is regulated by Iκβα proteins, and they inhibit NF-κB triggering. The Iκβα expression was suppressed in LPS-induced septic rats. Gedunin inhibited the degradation of Iκβα.

Discussion

Septic shock is one of the stages of SIRS, which subsequently causes multiple organ failure. An endotoxin, LPS, is a powerful stimulator that activates macrophages or monocytes in order to produce assorted pro-inflammatory cytokines.1, 2 The LPS-prompted septic rat model behaves like a human disease.13, 14 Sepsis causes uneven immune reactions, oxidative stress and mitochondrial disorders.11, 12 Meanwhile, an immune reaction in sepsis is an exceptionally complex single antimicrobial remedy that appears to be enough to increase survival. Antioxidants play a defensive role in sepsis-associated inflammation and oxidative stress.13, 19 The efficacy of medications in sepsis treatment via LPS-triggered cytokines and stimulated signals has been reported.13, 14, 33, 34 Thus, we aimed to evaluate the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of GN on an LPS-induced rat model. Gedunin significantly reduced cytokines, chemokines and pro-inflammatory mediators, and enhanced the antioxidant activities in our LPS-prompted septic rat model. Numerous studies have previously proposed that GN exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities in lung inflammation, acute articular inflammation and LPS-induced inflammation models.30, 33, 34

The generation of increased free radicals leads to oxidative damage. Extreme oxidative stress is a unique feature of LPS. Sustained vascular inflammation and oxidative stress due to LPS stimulation are distinctive features in sepsis.18 The antioxidant resistance is due to a variety of antioxidants: CAT, SOD and GSH-Px. Our study shows that LPS modifies the antioxidant enzymes and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), and GN treatment prevents oxidative stress. Increased TBARS formation and reduced antioxidant levels confirm LPS-induced lipid peroxidation. Gedunin treatment inhibited this peroxidation. This result is in agreement with previous studies which reported that GN, neem leaf and bark extract reversed elevated MDA levels and enhanced the antioxidant status.36, 37 Hence, GN could reduce oxidative stress and exert protection against free radicals generated by LPS-induced sepsis in rat models.

Numerous studies have indicated that inflammatory cytokines, particularly TNF-α, play a vital role in LPS-prompted sepsis and endotoxin shock.16 Tumor necrosis factor alpha, a pleiotropic cytokine, is responsible for multiple physiological functions and is released by various immune cells due to LPS triggers.38 The ELISA tests identified LPS serum cytokines in rats. Lipopolysaccharide enhanced the levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-10, IL-1β, and IL-6) and GN reduced them. These results establish that GN can constrain the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and block inflammatory reactions. Previous reports have also suggested that GN reduces inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators in experimental animals.33, 34 The HMGβ1 functions as an extracellular signal molecule and has a role at the molecular level in inflammation, cell diversity, relocation, and metastasis.39 In an earlier study, an increase in HMGβ1 led to a subsequent increase in TNF-α, which resulted in the release of IL-6, reflecting co-activation between early inflammatory cytokines and HMGβ1.40 The HMGβ1 acts as a controller or modulator in the organ responses to sepsis. In the current trial, HMGβ1 was significantly augmented in the LPS-induced septic rats, and significantly reduced in the GN-treated animals. Thus, GN prevents the inflammatory reaction of sepsis in the lungs by attenuating HMGβ1 and thus protects against lung damage. To the best of our knowledge, the action of GN on HMGβ1 has not been previously explored. Our study is the first one to reveal the impact of GN on HMGβ1.

Recently, it has been discovered that HMGβ1 amplifies TLR-facilitated activation of NF-κB.41 Nuclear factor kappa B plays a crucial role in controlling the gene transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines.42 Preceding trials have explored the pathways of NF-κB stimulation and signal transduction in the pathophysiology of sepsis. The NF-κB, a transcription element, prompts an upsurge of cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) to initiate inflammation and apoptosis.43, 44 The multi-protein signaling complexes, such as inflammasomes, promote the stimulation of caspases and IL-1β. The NLRP3 is a renowned inflammasome that is associated with autoimmune disorders. It is also a key target for anti-inflammatory treatments.45 Control of HMGB1 improves inflammation and sepsis-promoted lung damage by restraining NLRP3 through the NF-κB pathways.46 Our findings demonstrate that GN causes anti-inflammatory action in septic lungs by subduing NF-κB activation, which results in reduced levels of HMGβ1, NLRP3 and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, GN protects against lung impairment.

Sepsis causes hyper-expression of inflammatory moderator systems to produce cytokines. The NF-κB stimulation is key to those principal systems.47 The suppression of NF-κB reduces acute inflammatory changes and organ impairment in sepsis. In the current research, we proposed that GN could mitigate hepatic phosphorylated NF-κBp65. Earlier reports found that MRP-8 openly interrelates with TLR-4/MD-2 and persuades NF-κB stimulation.48 The MRP8 promotes MyD88 intracellular translocation and the initiation of IRAK-1 and NF-κB that subsequently upregulates TNF-α expression.48 Our study documents that GN diminishes MyD88, IRAK-1 and NF-κBp65 adaptor protein expressions. Hence, the protective effect of GN could be mediated by the suppression of other inflammatory molecules involved in the NF-κB pathway. Nevertheless, further investigations over a longer period of time should assess if there are any side effects associated with GN treatment before human use.

Limitations

The current study showed that GN significantly reduced cytokines, chemokines and pro-inflammatory mediators, and enhanced the antioxidant activities in the LPS-prompted septic rat model. However, one should note that except for IL-6, none has found its way from bench to bedside. Interestingly, GN is the promising candidate to control the sepsis, but further clinical research is needed.

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time that GN could mitigate ROS in organs (liver, kidneys and lungs), and it could reduce pro-cytokines, lessen hepatic toxicity, reduce tissue damage, and enhance antioxidant activity in the LPS-induced septic rat model. We also discovered that GN treatment alleviated the MyD88, IRAK-1, TRAF-6, and NF-κB protein levels and subdued Iκβα degradation in the LPS-induced septic rat model through its anti-inflammatory effects. While these results may be due to the powerful antioxidant properties of GN, they may also be caused by the repression of the intensified inflammation cascade. This suppression prevents serious impairment by attenuating HMGβ1, NF-κB and NLRP3 levels and averts a cytokine storm. Our findings imply that GN is a potential remedy for sepsis due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Further research is required to confirm the antiseptic activity of GN on various signaling pathways in an in vivo model.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8297655. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 1.

Supplementary Table 2. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 2.

Supplementary Table 3. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 3.

Supplementary Table 4. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 4.

Supplementary Table 5. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 5.

Supplementary Table 6. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 7.

Supplementary Table 7. Results of normality test as presented in Figure 8.

Supplementary Fig. 1. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 1.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 2.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 3.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 4.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 5.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 7.

Supplementary Fig. 7. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 8.