Abstract

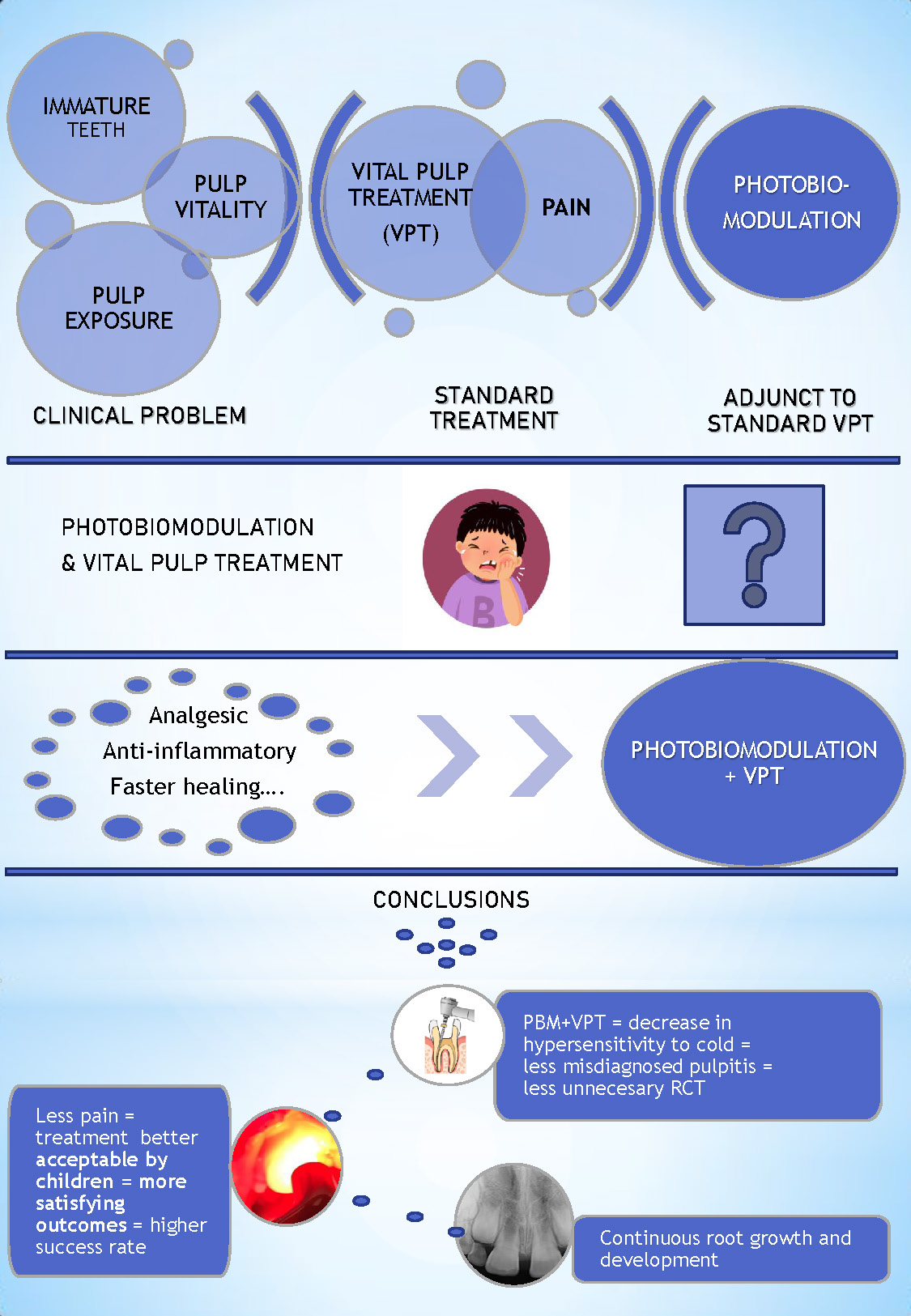

Background. Minimally invasive endodontics is recommended for young, immature teeth to preserve healthy pulp and dentin tissue.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to examine the cold sensitivity of immature teeth that received photobiomodulation (PBM) after vital pulp therapy (VPT).

Materials and methods. The study followed the STROBE guidelines and included 123 healthy patients aged 8–13. The immature teeth (incisors, premolars and molars) that qualified for VPT received the bioceramic material – Biodentine. In this experiment, teeth were treated immediately and at 24 h post-VPT with a 635-nm diode laser using a power of 100 mW, a power density of 200 mW/cm2 and a total energy of 4 J (PBM group, n = 43), while those not treated were the control group (n = 43). The tooth sensitivity to cold was measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS) before and at 6 h, 1 day, 7, 30, and 90 days after treatment. The predictor variable was PBM skills regarding the ability to decrease cold sensitivity after VPT. The primary endpoint was the time to reverse hypersensitivity to cold, and the secondary endpoint was the occurrence of possible side effects. The Mann–Whitney U test, Friedman test along with Dunn’s post hoc test, and the χ2 test were used to investigate tooth sensitivity.

Results. Eighty-six immature permanent teeth of 86 children were included in the study. It was shown that the difference was significant for sensitivity to a cold stimulus between the groups at 6 h, 24 h, 7 days, and 30 days, but no difference was found preoperatively and at 90 days (6 h, 24 h, 7 days, and 30 days, p < 0.001, and 90 days, p = 0.079). However, patients in both groups reported a decrease in discomfort provoked by cold stimuli throughout the follow-up period.

Conclusions. Photobiomodulation decreased postoperative sensitivity and was more acceptable for patients. Further randomized clinical studies with placebo-controlled groups are needed.

Key words: dental pulp capping, calcium hydroxide (CH), dental pulp test, photobiomodulation therapy

Background

Young permanent teeth are teeth that have erupted and are present in the oral cavity but have not fully matured in morphology and structure, and have not established an occlusal relationship with their antagonists. The anatomical characteristics of these immature teeth include short clinical crowns, wide pulp cavities, thin hard tissues, short roots, and trumpet-shaped apical foramina. During the first 3–5 years after the eruption, the root formation process continues, and factors such as caries, developmental deformities and trauma can cause pulp lesions or even necrosis.1 The bacteria and toxins from necrotic pulp tissue can spread to the surrounding tissues, resulting in shortening of the root or even tooth loss.2 Since the apical orifice in immature teeth is wide and open, conventional root canal treatment (RCT) may not effectively control bacterial infections. In addition, due to the thin root canal wall and poor resistance, these teeth are prone to fracture even under physiological forces.3

Vital pulp therapy (VPT) is expanding its indications with the advancement of biomimetic oral materials and modern equipment, coupled with the deepening of basic oral research.4 The current trend in dentistry is minimally invasive treatment, especially in endodontics for young, immature teeth, with an emphasis on preserving healthy dentin and pulp tissue at every stage of clinical intervention, from diagnosis to preparation. While there is local inflammation and bacterial infections in cases of irreversible pulpitis, histological and micro-biological studies reveal that the entire pulp need not be removed as the inflammation and bacteria are generally confined to the local pulp tissue near the lesions.5 Pulp tissue a few millimeters away from the infected tissue and necrotic pulp is typically free of inflammation and bacteria.6 Furthermore, current research has shed light on the ability of dental pulp tissue to prevent bacterial penetration into the dentin by producing reactive or reparative dentin.7 The traditional approach to the complete removal of the pulp (RCT) once it is infected is being challenged by these new findings. Pulp tissue has the opportunity to self-repair by isolating itself from bacteria and toxins, and it is recommended to preserve it, especially in young permanent teeth where the healing potential is relatively high.8

The primary objective of VPT is to prevent pulpitis by stimulating the production of reparative dentin or a calcium bridge, which ensures the continued functioning of the affected teeth. The ultimate aim is to preserve pulp vitality and retain the affected teeth in the long run. The commonly used methods for VPT are pulpotomy and pulp capping. According to a recent study by Wu et al.,9 pulpitis-derived stem cells exhibit comparable proliferative capacity and multidirectional differentiation potential as dental pulp-derived stem cells, suggesting that it is possible to adequately preserve pulp in irreversible pulpitis without completely removing it. Vital pulp therapy for young permanent teeth includes indirect pulp capping (IPC), direct pulp capping (DPC), partial pulpotomy, and total pulpotomy. Among these techniques, IPC and DPC are more effective at preserving the entire pulp and enhancing tooth development, while partial pulpotomy and total pulpotomy are partial pulp preservation methods. The application of VPT methods varies, depending on the age group.10

After VPT, patients most often complain of hypersensitivity to cold.10 As pain is very subjective, it is difficult to calibrate the sensations registered by patients, especially in the case of young patients, who usually exaggerate pain. Nowadays, there is no recommended effective method to overcome this complication and to help patients deal with postoperative discomfort.10, 11 Several studies have proposed photobiomodulation (PBM) as an effective new attempt of pain control in medicine and dentistry that is well accepted by patients due to its high success rate.11, 12

Photobiomodulation was formerly known and described in the literature as low-level laser therapy (LLLT). After it had been reported that the use of not only coherent monochrome light sources, such as lasers, but also non-coherent light sources such as light emitting diodes (LEDs) was effective and led to similar biomodulation processes, the therapy received a new name in practice.13 Numerous effects of PBM have been identified in the literature, including improved cell regeneration and tissue formation by promoting the proliferation of stem cells, enhanced microcirculation and capillary development, as well as the production of analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects.12, 14

Thus, PBM has been used in dentistry following VPT due to its well-documented anti-inflammatory, regenerative and analgesic properties.11 Additionally, it has been reported that laser irradiation has a stimulatory effect on the dental pulp cells, odontoblasts. In fact, they release tertiary dentin, which is an important process in dentin bridge formation at the pulp exposure site.15

Objectives

The objective of this study was to clinically evaluate the effectiveness of PBM using a 635-nm diode laser in reducing postoperative sensitivity and pain following VPT in the immature teeth of young patients. Additionally, in both groups, the clinical success rates of VPT were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was conducted as a retrospective analysis and was granted the approval by the Local Ethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University’s Faculty of Dentistry (approval No. KB235/2021). All the participants and their parents provided informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Setting

The analysis included the results of PBM following VPT in children aged 8–13 years who received the treatment at the Department of Pediatric Dentistry of Poznan University of Medical Sciences, from October 2021 to October 2022, who had relevant clinical data from available patients’ records and met the inclusion criteria of the study. Data were collected from January 2023 to February 2023.

Participants

A total of 123 patients were selected for this study from the pool of children referred for routine treatment. Then, we identified a group of 86 children who fulfilled all the inclusion criteria for the study.

Variables

The data available for this study included the patient’s age and gender, treated tooth, and discomfort level measured with the visual analogue scale (VAS). The treatment was performed by a single operator and aimed to standardize the groups based on the number of clinical cases (i.e., age, gender and tooth).

The inclusion criteria for the study included patients aged 8–13 years with immature mandibular and maxillary permanent incisors, premolars, and molars that did not have any periodontal problems (i.e., probing depth was no more than 3 mm). All patients receiving 980-nm diode laser-assisted VPT with or without PBM were included. Pulpal exposure of 0.5–1.0 mm, occurring only on the occlusal side of premolars and molars, was also a requirement. In addition, patients had to be generally healthy, not requiring analgesics or antibiotics in the past 2 weeks, and not taking immunosuppressive drugs or requiring antibiotic prophylaxis. To participate in the study, all parents of the participants were required to sign a declaration of informed consent, based on the age of the patients. The patients’ data had to be accurately recorded and complete. Patients were excluded from the study if they required a second anesthetic, had undergone previous treatment and restoration, had severe tooth pain or pain that could not be localized, had taken pain medication prior to their visit, had problems with cooperation, or lacked data during follow-up.

Vital pulp therapy included cases with clinically vital (in cold test) and asymptomatic pulp, where mechanical exposure occurred during the preparation of caries in teeth isolated with a rubber dam. Indications for VPT were pulp exposure with controlled bleeding and the possibility of direct contact of vital pulp tissue with capping material, Biodentine, with adequate coronal seal due to the final restoration at the same visit.

In total, out of 123 teeth, only 86 teeth from 86 individuals were further examined and included in the study (43 children who received PBM after pulp therapy (PBM group) and 43 patients who did not receive PBM after the procedure (control group)).

Data sources

All data included in the study were collected from the patient’s dental records, examinations and radiographs.

Study size

The patients were chosen as participants of the study according to the inclusion criteria. No other criteria were used for the selection of the participants. The study size of 123 teeth included all VPT cases treated from October 2021 to October 2022 at the Department of Pediatric Dentistry.

Clinical procedures

Before the clinical examination, medical and dental anamnesis were obtained from both the parents and participants. The baseline preoperative pain level (VAS) and preoperative radiographs were recorded after stimulation with a cold thermal test. Cold spray (Coltene/Whaledent Inc., Mahwah, USA) was applied to a regular microbrush applicator (Ø 2.00 mm) and held on the healthy enamel for 5 s. Assuming pain produced by cold stimulation, a short-lived, sharp pain that subsides when the test is over (5 s) is considered normal for the pulp and reversible pulpitis, and was an inclusion criterion for the study.

If the pain was pronounced or exaggerated and lingered for more than 10 s after the removal of the microbrush tip, it was considered irreversible pulpitis and the patient was excluded from the study. Local anesthesia (4% articaine and epinephrine 1:200,000; Citocartin; Molteni Dental, Milan, Italy) and rubber dam isolation were used. The procedure was performed using ×6.4 magnification loupes (Exam Vision, Samsø, Denmark) and included the laser protocol. The cavity was prepared, and any carious tissue was removed using a sterile bur (Meisinger, Neuss, Germany). In cases where pulpal exposure occurred due to the removal of caries, a sterile saline-soaked cotton pellet was placed in the cavity for 2 min to control the bleeding. If the bleeding from the exposed pulp continued for more than 5 min, the patient was deemed to have irreversible inflammation of the pulp tissue and a pulpotomy or RCT was considered, resulting in the patient being excluded from the study based on the results.

Laser procedures

After 2 min, if bleeding control was successful, a 980-nm diode laser (SmartM PRO; Lasotronix, Piaseczno, Poland) was used for coagulation and cavity decontamination, as shown in Table 1.

The decontamination of the cavity was performed with a non-activated 400-µm fiber, in the defocused mode, with a 1-millimeter tip-to-target distance and a circular movement of 2 mm/s.

The coagulation protocol included the irradiation time of 2 s and a tip-to-target distance of 1 mm. The procedure was repeated until the denaturation effect was achieved on the exposed pulp. When the hemorrhage was controlled, Biodentine (Septodont, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France), mixed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, was placed on the area of pulp exposure. After 20 min, a Single Bond Universal (3M, Maplewood, USA) and dual-cure composite PREDICTA BULK Bioactive (Parkell, Edgewood, USA) were placed as a final restoration. Control radiographs were taken at the end of the visit.

PBM procedure

A 635-nm diode laser (SmartM PRO; Lasotronix) was used for PBM irradiation under the parameters described in Table 2. After VPT, the first session of laser irradiation was performed at the apex area from the buccal and lingual side using a contact technique. The second session of PBM was conducted 24 h after treatment (Table 2).

To prevent any harm during laser application, safety glasses were provided to both the clinicians and patients. A control group was also established by selecting non-irradiated patients.

Follow-up

The effectiveness of PBM was assessed at various follow-up points after VPT, including 6 h, 24 h, 7 days, 30 days, and 90 days. Postoperative sensitivity was evaluated using a thermal test (cold spray) and recorded using VAS, which features a 10-cm scale with no pain representing the value of 0 and unbearable pain representing the value of 10. Patients and parents were instructed to record pain intensity at home for 6 h, specifically for tooth sensitivity caused by cold beverages. At the 24-hour and 7-day follow-ups, pain levels were evaluated using VAS. Additionally, the PBM group underwent a second session after 24 h. Clinical and radiographic examinations were conducted at 1 and 3 months post-VPT. The treatment success was defined as the absence of clinical symptoms and complete radiographic development of the apical area, while failure was indicated by inflammatory signs, periapical lesions, pulp necrosis, and uncontrollable pain, necessitating a referral for RCT.

Statistical analyses

The analysis of the statistical data was conducted using 2 software programs: Statistica® v. 13.5.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA) and PQStat 1.8.0.414 (PQStat software, Poznań, Poland). The results were compared before and after PBM with regard to the evaluation time and grouping. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparing 2 independent groups, while Friedman test with Dunn’s post hoc test was employed for comparing more than 2 paired groups. Categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 test. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05.

Quantitative variables

Quantitative variables were analyzed and compared in terms of mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD), median, minimum and maximum values, interquartile range (IQR), absolute numbers, and/or percentages as per suitability.

Results

The study was performed at the Department of Pediatric Dentistry of Poznan Medical University, Poland, between October 2021 and October 2022. From a pool of 123 cases, as documented in VPT records, only 86 directly capped immature permanent teeth met all the inclusion criteria. The PBM group and the control group included 43 teeth each, according to the study protocol. The baseline characteristics of the subjects revealed no differences in age, gender and tooth location between the PBM and control groups. The patient distribution is presented in Table 3.

Thermal sensitivity assessment (VAS)

In this study, the Friedman test with Dunn’s post hoc test and the χ2 tests were used to investigate the discomfort duration (sensitivity to cold) in the PBM and control groups. After conducting thermal tests at the 3 postoperative follow-up periods, lower pain scores were observed in the PBM group compared to the control group (Figure 1A,B).

The difference in sensitivity to a cold stimulus was significant between the groups at 6 h, 24 h, 7 days, and 30 days, but no difference was found preoperatively and at 90 days (p6h,24h,7 days,30 days < 0.001 and p90days = 0.079). A significantly greater decrease in VAS scores was observed in the PBM group than in the control group, while both groups showed a reduction in discomfort throughout the follow-up period, as shown in Figure 1A,B.

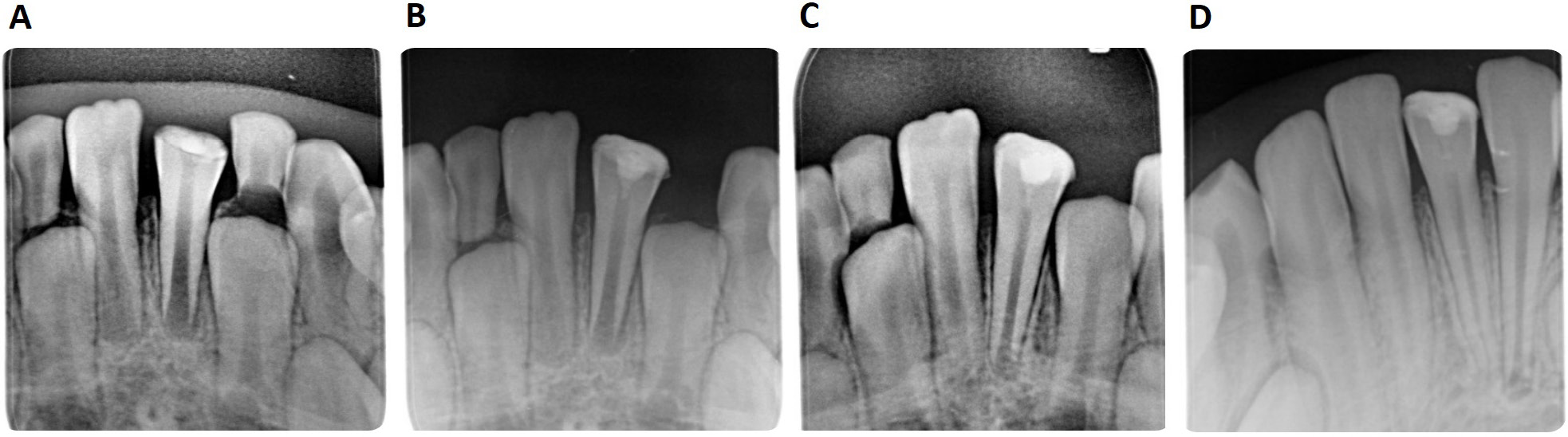

VPT success rate

The success rate analysis showed a success rate of 93.02% in the PBM group (40/43) and of 81.4% (35/43) in the control group. The overall success rate of VPT in our study was 87.2% (75/86). This showed a recorded failure of VPT in 11 cases in total. Three cases failed in the PBM group and 8 in the control group. No statistically significant difference was observed in success rates between the groups (p = 0.10646, Table 4). The radiological treatment success is presented in Figure 2.

Discussion

Based on our study, it has been found that PBM following the VPT procedure could be an effective approach to increase not only the comfort of patients with postoperative pain but also the success rate of the treatment itself. Prolonged sensitivity to cold might be a false indication for RCT, especially when misdiagnosed in young patients, who often exaggerate sensations or have a problem with their evaluation. The findings revealed a decrease in pain levels on the VAS during the 3 postoperative follow-up periods among the PBM group, compared to the control group. Specifically, a notable reduction in pain scores was observed in the PBM group on day 7. Additionally, when comparing the discomfort relief between the preoperative period and each follow-up period, the PBM group demonstrated a considerably higher level of pain relief than the control group (primary endpoint), with no reported complications.

Several studies have demonstrated that sensitivity to cold is a frequent complication following the VPT procedure.16, 17 The varied levels of pain and discomfort experienced by patients, particularly young ones, are unpleasant. Prolonged pain and difficulties in objectively evaluating such sensations have been deemed treatment failures. Despite the significance of the issue,15, 16, 17, 18 a definitive strategy for addressing postoperative pain and sensitivity has yet to be identified. Currently, PBM is being utilized as an additional technique in VPT to address postoperative sensitivity and improve the success rate of treatment. It has been proven that PBM, a non-invasive approach to the biomodulation of the dental pulp, utilizes low-level energy lasers. Though it does not provide total anesthesia (complete insensitivity to sensation), similar to infiltrative local anesthesia, it alters the behavior of neuronal cell membranes, temporarily impeding the Na-K pump, thereby interrupting impulse transmission and leading to a painkilling effect.19

Broadly, there are 2 recommended techniques for using lasers in VPT. The first one involves the direct application of the laser on the exposed pulp to promote coagulation and decontamination. The 2nd method involves using low-power lasers to arouse systemic responses from tissues.19 Several studies have used various laser wavelengths with different parameters for irradiating exposed pulp tissue using the first technique, and have reported higher success rates than for the other method. For instance, a carbon dioxide laser (10,600 nm) was employed as a supplement to DPC in a study conducted by Moritz et al.20 The use of 635-nm and 980-nm diode lasers in VPT offers several benefits that contribute to better results in the laser-treated group. These benefits include efficient decontamination due to the laser’s ability to penetrate deeply into the dentin and scatter significantly. The hemostatic effect is achieved through the laser’s absorption by hemoglobin and melanin. Additionally, the biostimulation effect of the laser results in reduced inflammation and pain, increased cell proliferation and migration, dentinogenesis and cytodifferentiation of odontoblast-like cells, as well as the synthesis of the dentin extracellular matrix leading to the formation of reparative dentin.21, 22 The success rates of laser treatment were reportedly higher than those of calcium hydroxide alone, as noted in the Santucci’s study.21 In a study by Olivi et al., different power parameters and durations of Er:YAG lasers as an adjunct to DPC did not show any significant difference in success rates compared to other studies.22 Moosavi et al. conducted a study to evaluate the effectiveness of PBM in reducing postoperative sensitivity in patients with class V cavities.12 Their findings showed that patients who received PBM had significantly lower pain scores on days 1, 14 and 30, compared to those in the placebo group. Our study showed an overall success rate of 87.2% for VPT, with a success rate of 93.2% in the PBM group and 86.1% in the control group. However, there were no significant differences in the treatment success between the 2 groups. There are limited studies on postoperative pain following VPT stimulated by cold, with variations in factors such as pulp capping material, irradiation parameters and tooth type, making it difficult to compare the results.

Despite using a different laser application technique, our study showed a significant decrease in pain levels in the PBM group on day 7, similar to the findings of the previous study.23 While pain levels in the PBM group significantly decreased at all 3 follow-up points, there was no significant difference in the control group. However, treatment outcomes may vary based on factors such as laser wavelength and power settings, with some studies recommending lasers with a wavelength of 700–1070 nm and 250–500 mW power, and emphasizing the importance of the proper application technique.23, 24, 25 In our study, we applied the laser at the buccal and lingual gingiva over the apex, using an 8-millimeter probe to prevent potential tissue damage. Unlike other studies, we applied the laser to the periapical area for pulp tissue biostimulation, without intervening in the filling. The aim was to determine PBM’s ability to decrease postoperative sensitivity to cold after VPT in immature teeth, where tissue formation requires the presence of vital pulp and irradiation influences microcirculation in the periapical area by eliminating toxins and improving blood supply to the pulp.

Research has shown that the type of pulp capping material can affect the outcome of VPT.26, 27 While calcium hydroxide (CH) was previously the standard for DPC, it has become less popular due to its lack of sealing ability, degradation over time and inefficient biocompatibility. Recent studies have demonstrated better clinical outcomes with the use of mineral trioxide aggregates (MTA) or Biodentine in VPT.26, 28 For this reason, Biodentine was chosen as the pulp capping material for this study. While CH had a 13% success rate in the several studies published in recent 10 years, DPC with MTA showed an 80% success rate after 2 years of follow-up.28 However, some researchers have reported similar outcomes for CH and MTA.29, 30 Nowadays, MTA is the preferred standard capping material for DPC due to its favorable properties, such as increased transcription factor levels and better biocompatibility.31, 32 TheraCal and Biodentine may also be used as alternative materials for indirect pulp therapy (IPT) in young permanent teeth, with a success rate of approx. 95.83% based on radiographic and clinical results.33 A recent study by Sharma et al. showed that combining laser treatment with the use of Biodentine has an additional effect on the formation of tertiary dentin.34 By penetrating dentinal tubules, the antibacterial laser can accelerate the formation of dentin bridges in deep caries lesions and improve the success rate of the procedure. In our study, Biodentine was used as the standard material for all VPT procedures due to its superior properties and higher success rate compared to CH in the long term.35, 36 Additionally, the PBM group showed a significantly greater decrease in hypersensitivity than the control group on the first 3 evaluation time points, with no reported side effects after VPT.

Limitations

This research presents a new alternative to alleviate postoperative hypersensitivity after VPT. Photobiomodulation is a secure, non-invasive and uncomplicated approach to decrease pain and discomfort following VPT. To establish PBM as an adjuvant therapy and minimize discomfort during pulp capping procedures, extended follow-up periods and laser applications with diverse parameters must be examined. Patient age is also a critical factor to consider. Researchers have suggested that DPC is more efficient in patients under 40 years of age.36, 37 Thus, we focused on individuals aged 8–13 years with immature young permanent teeth indicating unfinished root development. Notably, there are no existing data on this topic in the literature, making a direct comparison of our findings challenging. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, no sample size calculations were performed, and all appropriate patients who underwent laser application, VPT, or VPT alone during the specified study period were included. A significant limitation of our study is the non-randomized distribution of samples and the lack of evaluation of various wavelengths and capping materials. Moreover, our retrospective study had no placebo-controlled group, and the subjects, irradiation operators and examiners who performed the assessment and analyses were not blinded. The irradiated parameters were not calibrated or validated before each application, which could also affect the results.

Conclusions

The study revealed significantly lower tooth sensitivity to cold stimulus for PBM application measured after 6 h and 1, 7, and 30 days. The results obtained after 3 months were insignificant. The present study introduced PBM as a reliable, secure and non-invasive technique to improve patient comfort by minimizing pain and discomfort after VPT procedures, especially in the initial postoperative period, the most important for diagnostic concerns. However, as this was a preliminary study, further randomized clinical studies with placebo-controlled groups are essential to explore PBM with various wavelengths and different capping materials.