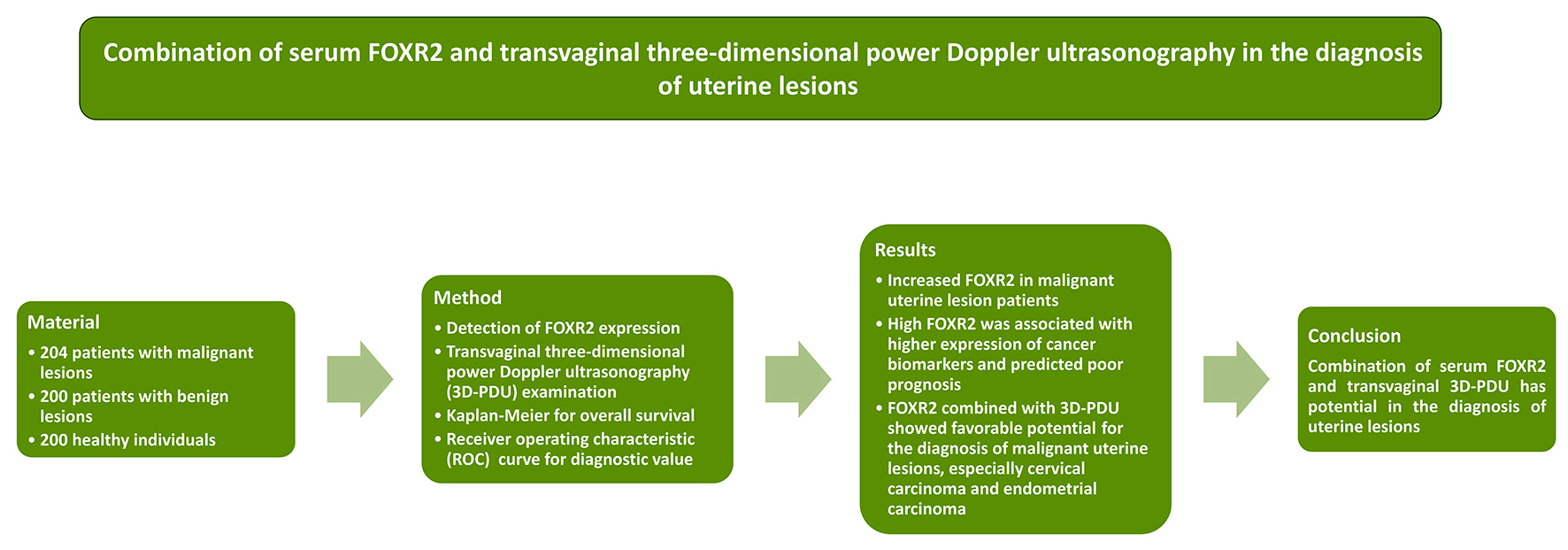

Abstract

Background. Cervical carcinoma and endometrial carcinoma are the most common gynecologic cancers worldwide. Forkhead-box R2 (FOXR2) plays an important role in the progression of various malignant tumors. However, the effects of FOXR2 on the development of uterine lesions remain unclear.

Objectives. This prospective observational study aimed to investigate the diagnostic performance of FOXR2 and transvaginal three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography (3D-PDU) for malignant uterine lesions.

Materials and methods. This study included 404 uterine lesion patients and 200 healthy individuals who visited the hospital for a physical examination from April 2014 to May 2016. All patients received FOXR2 detection and 3D-PDU examination at admission. The demographic data and clinical data, including age, body mass index (BMI), and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, were collected. All the patients were followed up for 5 years. The overall survival (OS) was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier (K–M) curve analysis. The diagnostic value of FOXR2 and 3D-PDU was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results. Serum levels of FOXR2 mRNA were upregulated in patients with malignant uterine lesions. Patients with high expression of FOXR2 showed a higher expression of the cancer biomarkers CA125, CA199, CEA, and SCCA. It was also found that FOXR2 expression was associated with the clinical outcomes of patients with malignant uterine lesions. Moreover, higher expression of FOXR2 predicted a poor prognosis. The combined use of FOXR2 and 3D-PDU showed favorable potential for the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions, especially for cervical carcinoma and endometrial carcinoma.

Conclusions. The combination of serum FOXR2 and transvaginal 3D-PDU has a potential in the diagnosis of uterine lesions.

Key words: diagnosis, FOXR2, 3D-PDU, uterine lesions

Background

Cervical carcinoma and endometrial carcinoma are the most common gynecologic cancers in developed countries, ranking 2nd and 4th, respectively, in malignant tumors of the female reproductive system.1, 2, 3, 4 In the last decade, the incidence and mortality rates of malignant gynecologic cancers have been increasing year by year.5, 6, 7 As reported, the 5-year survival for cervical carcinoma patients with high tumor stage is no more than 60%.8 Although huge progress has been made in the treatment, such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the long-term survival for patients with tumor metastasis is still not satisfactory.9, 10, 11 Therefore, finding a novel diagnostic method is important.

Three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography (3D-PDU) is a new imaging technique widely used in gynecology, especially in gynecologic oncology.12, 13, 14 The 3D-PDU exhibits a similar diagnostic performance as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in predicting deep myometrial invasion and cervical involvement for endometrial cancer staging.15, 16, 17 Zhang et al. found that combined applications of 3D-PDU and MRI showed a better effect on the staging diagnosis of endometrial cancer with hepatitis B virus infections than a single examination using 3D-PDU or MRI.18 Several biomarkers are proven to be associated with the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma, including CA125, CA15-3, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA.19, 20, 21 Among these biomarkers, forkhead-box R2 (FOXR2) is involved in gynecologic oncology. A previous study revealed the upregulation of FOXR2 in the tissues of patients with ovarian cancer, suggesting an obvious association of the biomarker with the prevalence of ovarian cancer.22 Another study demonstrated that FOXR2 accelerated tumor metastasis and the growth of ovarian cancer cells by stimulating angiogenesis and activating the Hedgehog signaling pathway.23 However, the evidence shows that FOXR2 serves as a tumor promoter in different cancers, such as human colorectal cancer,24 lung cancer25 and thyroid cancer.26 The clinical significance of FOXR2 in uterine lesions needs further investigation.

Objectives

We conducted an observational study to investigate the association between the expression of FOXR2 and the prognosis of uterine lesion patients, and analyze the diagnostic performance of combined applications of FOXR2 and 3D-PDU for uterine lesions.

Materials and methods

Participants and samples

Our prospective observational study included 404 uterine lesion patients who reported to Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital (The First Hospital Affiliated with Hunan Normal University), Changsha, China, for treatment between April 2014 and May 2016. All patients were diagnosed with uterine lesions through histological analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) no history of severe drug allergy; 2) no serious cardiovascular diseases, including uncontrolled hypertension, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, heart failure, or myocardial infarction; and 3) patients without dyspnea or severe pulmonary insufficiency. The following patients were excluded: 1) patients who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before the study; 2) patients who underwent a traumatic operation before examination, such as hysteroscopy and diagnostic curettage; and 3) patients with other cancers. The tumor stage was evaluated according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria.27 Additional 200 healthy female patients who visited the hospital for physical examinations during the same period were enrolled in our study as controls. Blood samples were collected from all participants. The tumor tissues of all patients were obtained and immediately stored at −80°C for the following analysis. Fasting peripheral venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from all patients within 24 h of admission and stored at −80°C for the following experiments. This study obtained the approval from the Ethics Committee of the Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital (The First Hospital Affiliated with Hunan Normal University, approval No. HuNPPH-20150058). Written informed consent was provided by all participants. The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Calculation of sample size

The following formulas (Equation 1,Equation 2) were implemented:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

Minimal sample size (N) = max (NSEN, NSPE), where α stands for the test level, d indicates the tolerance error, Z represents the Z score, Z1-α/2 indicates that the sample follows a standard normal distribution, Z1-α/2 is identified as 1.96, SEN stands for sensitivity, SPE indicates specificity, and P represents the prevalence of disease.

The mean SEN value was 0.828 and the SPE level was 0.834, according to previous studies. The p-value was 0.456 for the prevalence of malignant uterine lesions, and 0.544 for the prevalence of benign lesions. Thus, α = 0.05, Z1−α/2 = 1.96, d = 0.1, NSEN = 120, NSPE = 98, and minimal sample size (N) = 120.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNAs were extracted from serum samples using Trizol reagent (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). The RNA concentrations were detected using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Subsequently, reverse transcription of RNA was conducted using a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan), and the target genes were quantified using ABI PRISM7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, USA) with the SYBR Premix ExTaq (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primers were used: F 5’-ACTGGGTCTCATGATGGTGG-3’ and R 5’-CTCCATCCAGGAGGTGATCT-3’ for FOXR2 and F 5’-TAGACTTCGAGCAGGAGATG-3’ and R 5’-ACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTG-3’ for β-actin. The β-actin was utilized as an internal control, and the relative expression of FOXR2 mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Transvaginal three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography (3D-PDU)

The vaginal volume probe with the power Doppler mode (Voluson E8; GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA) was used to examine the uteri of all patients. The sampling volume was placed on the color central blood flow, adjusted to about 5 mm from the edge of the tumor. Subsequently, the piezoelectric chip of the probe was rotated automatically at a 90° angle to scan the whole lesion. A complete three-dimensional power Doppler image was obtained. The thickness, shape, echo, and integrity of the endometrial contour, the location, number, size, shape, boundary, echo, and surface of lesions, as well as the relationship between basement and endometrium, were evaluated. The Virtual Organ Computer-aided Analysis (VOCAL) software (GE Healthcare) for the 3D power Doppler histogram analysis with computer algorithms was used to analyze the indices of blood flow and vascularization, including the vascularization index (VI), flow index (FI) and vascularization flow index (VFI).

Data collection and follow-up

Demographic data of all patients, including age, body mass index (BMI) and tumor stage, were collected. Serum levels of cancer-related biomarkers, including serum CA15-3, CA125, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA, were determined using chemiluminescence immunoassay, as reported in a previous study.28 All patients were followed up for 5 years from admission to death or the last follow-up.

Statistical analyses

First, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov analysis was used to confirm whether the data were normally distributed. The normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD), and non-normally distributed data were presented as median with range. The heterogeneity of variance was analyzed using Levene’s test. For normally distributed data (data expressed as M ±SD), the comparison between 2 groups was conducted using Student’s t-test, while the non-normally distributed data (data expressed as median with range) were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The rates were compared with the χ2 test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the diagnostic value. A Kaplan–Meier (K–M) curve with a log-rank test were used to examine the survival time. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were made using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and GraphPad v. 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) software.

Results

Basic clinical characteristics of all patients

This prospective observational study included 204 cases of malignant uterine lesions, 200 cases of benign lesions and 200 healthy controls. All participants were consecutively enrolled. Compared to the benign lesion group, the malignant lesion group had higher serum levels of CA15-3, CA125, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA, and a higher ratio of positive human papillomavirus (HPV). No significant difference was found for age and BMI between the malignant lesion group and the benign lesion group, as well as between the uterine lesion group and the healthy group (Table 1).

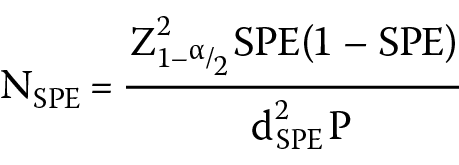

Serum levels of FOXR2 were elevated in malignant uterine lesion patients

Subsequently, the expression of FOXR2 in serum samples and tissue samples was determined. As shown in Figure 1A, the serum FOXR2 expression was notably upregulated in all uterine lesion patients, including benign lesion patients, compared to healthy controls (p < 0.001). The FOXR2 expression in tissue samples was increased in all malignant uterine lesion patients, endometrial carcinoma patients and cervical carcinoma patients compared to benign uterine lesion patients (Figure 1B, p < 0.001). These findings illustrate that FOXR2 expression is upregulated in patients with malignant uterine lesions.

Serum FOXR2 was associated with cancer-related biomarkers and clinical outcomes of malignant uterine lesion patients

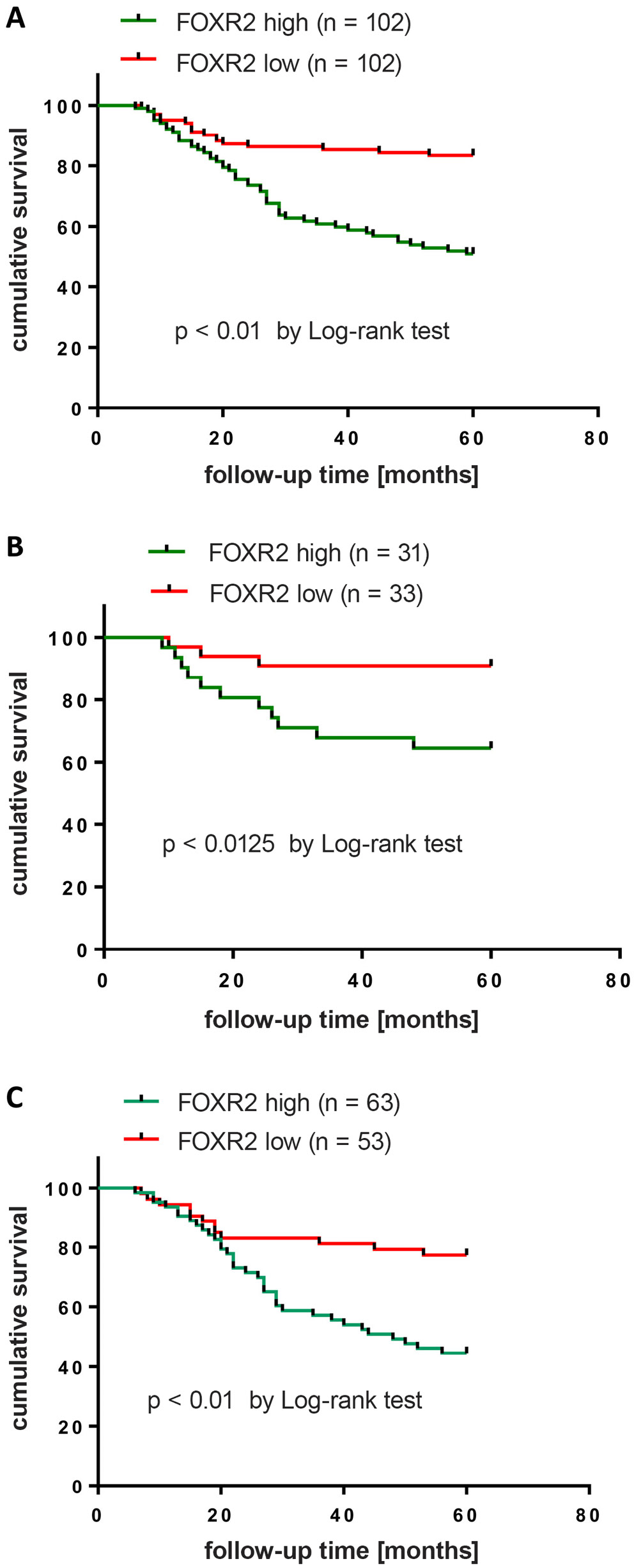

To further investigate the role of FOXR2 in uterine lesions, all malignant uterine lesion patients were divided into 2 groups, namely a high FOXR2 expression group and a low FOXR2 expression group, according to the median value of FOXR2 mRNA (0.855 compared to β-actin). Basic characteristics, including levels of tumor markers and the rate of positive HPV, were detected. As shown in Table 2, serum levels of CA15-3, CA125, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA were significantly higher in the high FOXR2 group than in the low FOXR2 group for all malignant lesion patients and cervical carcinoma patients (all p < 0.001). However, endometrial carcinoma patients with high/low FOXR2 expression showed no significant difference in SCCA expression. Additionally, the ratio of positive HPV (p < 0.001 for all comparisons), advanced FIGO stage (p < 0.001 for malignant lesions and cervical carcinoma, χ2 = 11.746 and p = 0.001 for endometrial carcinoma), lymph node metastasis (LNM) (p < 0.001 for malignant lesions and cervical carcinoma, χ2 = 8.749 and p = 0.003 for endometrial carcinoma), and distant metastasis (p < 0.001 for malignant lesions and cervical carcinoma, χ2 = 8.749 and p = 0.003 for endometrial carcinoma) were notably higher in patients with high expression of FOXR2. We further identified the early diagnostic value of FOXR2 for malignant lesions. As shown in Table 3, the ratio of patients with high FOXR2 expression increased along with the FIGO stage in all malignant lesion patients. The K–M curve analysis showed that patients with high FOXR2 had a shorter 5-year survival time compared to those with low FOXR2 in all malignant lesion patients (Figure 2A, p < 0.001), endometrial carcinoma patients (Figure 2B, χ2 = 6.235 and p = 0.0125) and cervical carcinoma patients (Figure 2C, p < 0.001). These findings suggested that higher FOXR2 expression predicted poor clinical outcomes and prognosis for patients with malignant lesions.

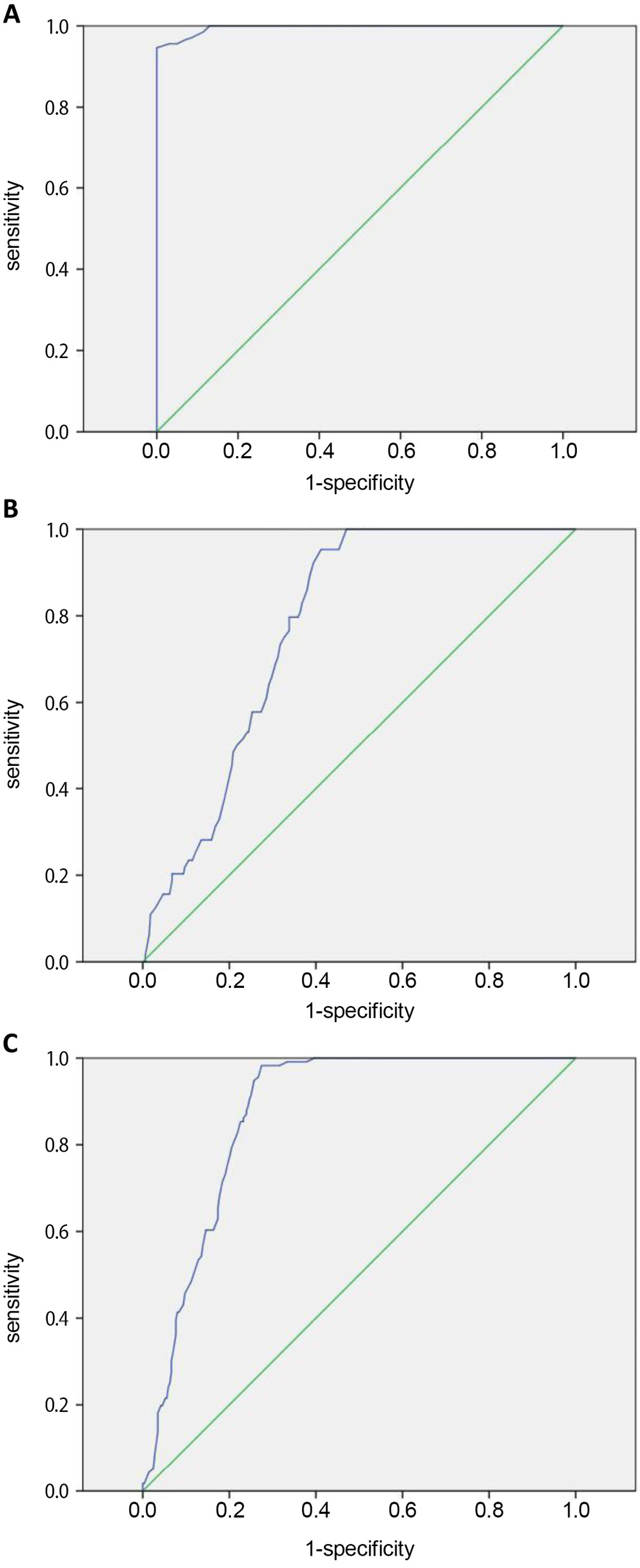

Diagnostic value of serum FOXR2 in benign/malignant uterine lesions

Next, a ROC curve analysis was performed to analyze the diagnostic value of FOXR2 in malignant uterine lesions. The cutoff value of FOXR2 mRNA for malignant uterine lesions was 0.545 compared to β-actin, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.996, sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 87.0% (p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.992–0.999, Figure 3A). The cutoff value of FOXR2 for the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma was 0.645 compared to β-actin, with an AUC of 0.776, sensitivity of 81.3% and specificity of 63.5% (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.730–0.823, Figure 3B). The cutoff value for FOXR2 in the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma was 0.605 compared to β-actin, with an AUC of 0.871, sensitivity of 98.3% and specificity of 75.3% (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.838–0.905, Figure 3C). These findings suggested that serum FOXR2 levels might serve as a potential diagnostic marker for malignant uterine lesions. Furthermore, FOXR2 showed satisfactory diagnostic value for endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma.

Combination of serum FOXR2 and transvaginal 3D-PDU in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions

Finally, the combined application of serum FOXR2 and transvaginal 3D-PDU in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions was analyzed. All patients received a transvaginal 3D-PDU examination at admission. A cutoff value of 0.545 for FOXR2 mRNA was considered diagnostic for malignant uterine lesions, as was a FOXR2 mRNA of 0.645 for endometrial carcinoma and FOXR2 mRNA of 0.605 for cervical carcinoma. As shown in Table 4, the application of FOXR2 combined with 3D-PDU exhibited satisfactory potential in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions, with a sensitivity of 96.65%, specificity of 97.44% and accuracy of 97.03%. Moreover, the application of FOXR2 combined with 3D-PDU showed a sensitivity of 79.69%, specificity of 99.17% and accuracy of 98.27% in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma, and a sensitivity of 95.65%, specificity of 70.49% and accuracy of 77.67% in the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma. The above results illustrated that FOXR2 combined with transvaginal 3D-PDU might be useful in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions, including endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma.

Discussion

Although the diagnostic methods for uterine lesions have developed in the last few decades, the early diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions still requires improvement.29, 30, 31 Reportedly, the 5-year survival rate for malignant uterine lesion patients with a high tumor stage is no more than 50%.32, 33, 34 Thus, finding early diagnostic methods and potentially novel biomarkers for malignant lesions of the uterus is of extreme importance. Our study illustrated that FOXR2 was increased in patients with malignant uterine lesions, and a higher FOXR2 expression was associated with a poorer prognosis and shorter 5-year survival time. Moreover, FOXR2, as well as the combined application of FOXR2 and transvaginal 3D-PDU, might be a potential method for the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions.

Emerging evidence states that FOXR2 is a tumor promoter responsible for the development of different cancers, such as liver cancer,35 lung cancer36 or prostate cancer, among others.37 As reported, FOXR2 was upregulated in breast cancer tissue and was remarkably associated with tumor size and LNM status, indicating that FOXR2 is an independent prognostic factor for breast cancer patients.38 Lu et al. found that FOXR2 promoted proliferation, invasion and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of human colorectal cancer cells.24 Nevertheless, limited studies have illustrated the role of FOXR2 in tumors of the female reproductive system. A previous study revealed that FOXR2 expression was elevated in endometrial adenocarcinoma (EAC), and an increased FOXR2 expression was related to a poor prognosis in EAC patients.39 The FOXR2 was also increased in epithelial ovarian adenocarcinoma tissue, and notable correlations between FOXR2 mRNA expression and EMT-related biomarkers were identified in ovarian adenocarcinoma patients with a high-grade cancer stage.22 In addition, another study found a greater upregulation of FOXR2 in paclitaxel (PTX)-resistant ovarian cancer tissues compared to PTX-sensitive ovarian cancer tissues.40 However, the role of FOXR2 has not been well investigated in uterine diseases, especially in endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma. In the present study, we demonstrated that FOXR2 was upregulated in malignant uterine lesion patients and was closely associated with levels of cancer-related biomarkers, namely CA125, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA. At the same time, the high expression of FOXR2 predicted poorer clinical outcomes and prognosis for patients with malignant uterine lesions.

The most recent study suggests that fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging is recommended for the assessment of various malignancies, such as lung cancer,41 hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma42 and breast cancer.43 The FDG PET/CT also exhibits good diagnostic performance in endometrial carcinoma44 and cervical cancer.45 Numerous studies report on the application of 3D-PDU in various diseases. Data show that the sensitivity of 3D-PDU is higher than that of digital rectal examination, grey-scale ultrasonography and power Doppler ultrasonography, but its specificity is lower.46 The 3D-PDU has been widely used in the diagnosis of benign and malignant uterine lesions. A previous study revealed that 3D-PDU exhibited higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting local recurrence or persistence in cervical carcinoma compared to serum markers (SSCA, CEA and CA125).47 Other research suggested that 3D-PDU imaging showed a potential in monitoring early therapeutic responses to concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT) in patients with cervical cancer.48 Belitsos et al. found the indicators of 3D-PDU to be positively correlated with cervical volume except for other pathological characteristics in cervical cancer patients.49 Furthermore, compared to early-stage ovarian tumors, the levels of vascular indicators of 3D-PDU were higher in patients with advanced-stage and metastatic ovarian cancers.50 The combination of the Mainz ultrasound scoring system with 3D-PDU enhanced its sensitivity and specificity in identifying benign and malignant pelvic tumors.51 Various biomarkers have been used in the diagnosis of malignant tumors, such as SSCA,52 CEA53 and CA125.54 However, the combination of biomarkers with 3D-PDU in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions was rarely addressed. The present study illustrated that the combination of serum FOXR2 and transvaginal 3D-PDU exhibited a potential in the diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions, especially for endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the samples were collected from a single center. Second, the molecular mechanism of FOXR2 in uterine lesions was not investigated. Third, the diagnostic value of 3D-PDU was not fully addressed. Further studies are needed to solve the above issues.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study illustrated that serum FOXR2 levels were upregulated in patients with malignant uterine lesions. The FOXR2 was associated with cancer-related biomarkers CA125, CA19-9, CEA, and SCCA. A higher expression of FOXR2 predicted poorer clinical outcomes and shorter 5-year survival times. Both FOXR2 and the combination of FOXR2 with transvaginal 3D-PDU showed potential in the early diagnosis of malignant uterine lesions, especially for endometrial carcinoma and cervical carcinoma. This observational study might provide novel research targets and new diagnostic methods for uterine lesions.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of the study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.