Abstract

There are contradictory findings regarding the effects of vitamin D supplementation and cigarette smoking on glucose metabolism in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Consequently, this meta-analysis focused on the association between vitamin D interventions and smoking cessation on glycemic control in T2DM patients. This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Cochrane Library, EMBASE and PubMed databases were used for a language-inclusive literature search until November 2022. The primary outcomes of this meta-analysis were changes in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level, vitamin D concentration and body mass index (BMI) values. This meta-analysis included 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 23,289 individuals with T2DM. Nine RCTs were related to vitamin D supplementation interventions, and 5 RCTs were related to smoking cessation interventions. The studies on vitamin D supplementation showed a substantial change in the intervention group, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.72 (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.58, 0.88; p = 0.001) and an odds ratio (OR) of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.78; p = 0.002); high heterogeneity was observed (I2 ≥ 95%). Similarly, the smoking cessation studies showed a substantial change in the intervention group, with a RR of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.99; p = 0.04) and an OR of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.74, 0.99; p = 0.04); high heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 87%). In conclusion, both vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation are associated with moderate BMI decline and an improvement of insulin sensitivity in people with T2DM.

Key words: glycemic index, smoking, type 2 diabetes mellitus, vitamin D deficiency, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a worldwide public health concern.1 Globally, 597 million individuals were suffering from T2DM by the year 20212 It is well documented that T2DM is a substantial risk factor for premature death and complications such as blindness, stroke, heart attack, amputation, and kidney failure.3, 4 Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic condition characterized by relative insulin deficiency, insulin resistance and elevated blood glucose levels.5 Vitamin D supplementation dramatically improves peripheral insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in people with T2DM who were recently diagnosed or are at high risk of developing the disease, by directly promoting pancreatic insulin production. Vitamin D acts through nuclear vitamin D receptors, since a particular receptor for vitamin D was found in the human insulin gene promoters (between 761 and 732 base pairs), which allowed it to control insulin expression.6 Considerable research has explored the relationship between circulating vitamin D concentrations and T2DM risk over the past few decades and has identified a high correlation between the two variables, but the results remain contradictory. For instance, Li et al.,7 Hu et al.8 and Łagowska et al.9 reported in their systematic reviews and meta-analyses that vitamin D supplementation improves the insulin sensitivity of target cells (liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue) and, consequently, improves beta-cell function, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level, insulin resistance, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) scores in T2DM patients. In contrast, Jamka et al.10 and Al Thani et al.11 showed that vitamin D supplementation had no effect on glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity.

Similarly, many studies have demonstrated that cigarette smoking increases the risk of vascular problems in T2DM patients and diabetes incidence in the general population.12 Smoking can influence glucose homeostasis by raising insulin resistance, lowering insulin production, or affecting pancreatic beta-cell function, and is linked to poor glycemic control in T2DM patients.13 Cigarette smoking and nicotine exposure, for instance, reduce the efficiency of pancreatic cells, leading to elevated insulin resistance in T2DM patients, as documented in a review paper by Maddatu et al.14 Contrary to this, Wang et al.15 found that smoking is negatively associated with insulin resistance in T2DM, likely due to increased weight gain upon nicotine withdrawal.

Since the available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed contradictory results, the present meta-analysis of RCTs investigates the influence of vitamin D and smoking on insulin resistance in T2DM patients.

Objectives

The aim of this meta-analysis was to assess the impact of vitamin D deficiency and cigarette smoking on insulin resistance in individuals with T2DM.

Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was undertaken following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data sources and literature search

An inclusive literature search was conducted without any restrictions on the year and language of publication using electronic databases, namely Cochrane Library, EMBASE and PubMed, up to November 2022. In addition, the bibliographies of relevant studies and meta-analyses were searched. The search strategy involved combinations of the following keywords: “type 2 diabetes mellitus”, “T2DM”, “insulin resistance”, “vitamin-D deficiency”, “vitamin-D supplementation”, “cigarette smoking”, “cessation of smoking”, “HbA1c”, “glycated hemoglobin”, “glycaemic index”, “meta-analysis”, and “systematic review”. Duplicate papers were deleted from the search results, followed by a title and abstract screening of the remaining articles. Finally, the full texts of the eligible studies were retrieved and reviewed, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study selection

The literature search was conducted separately by 2 authors. In the event of disputes, a consensus was obtained through discussion. The following conditions had to be met for a study to be eligible for the meta-analysis: (A) RCTs examining the effects of vitamin D deficiency on insulin resistance in T2DM; (B) RCTs examining the effects of cigarette smoking on insulin resistance in T2DM; and (C) studies evaluating the following outcomes: changes in vitamin D levels, HbA1c levels and body mass index (BMI) values. The exclusion criteria included clinical trials with a follow-up time of less than 1 month. Studies that were conducted on healthy volunteers or on those who suffered from type 1 diabetes mellitus were excluded from the study. Lastly, studies that compared factors other than vitamin D deficiency and cigarette smoking were not included in this meta-analysis.

Data extraction

A computerized data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) and utilized for the purpose of documenting the essential information of the studies16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 selected for the meta-analysis. This included the first author’s name, the year of publication, the intervention, the sample size in each group, the follow-up duration, and the study outcomes. Two different authors independently extracted the data, and their results were compared. In the case of divergent opinions, an agreement was obtained via discussion. Depending on the circumstances, a third author was also included.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Cochrane, London, UK) was applied in order to evaluate the methodological validity of each study that was incorporated into the meta-analysis. During the process of data extraction, selected articles were given a score, and RevMan v. 5.4.030 (Cochrane) was used to construct a quality evaluation graph.

Data analysis

RevMan v. 5.4.0 and MedCalc software31 were used throughout the procedure of data processing. The Mantel–Haenszel approach with the random-effects model29 was utilized in order to calculate the pooled risk ratio (RR) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each of the 2 outcomes. A result was considered statistically significant if its p-value was less than 0.05.32, 33 The RCTs that did not have any outcome events recorded in the investigation groups were excluded from the analysis of a particular outcome event because they did not contribute to the RR. Forest plots34 were used to visually represent the RRs and the 95% CIs. The I2 statistics were used to assess the level of heterogeneity present in the results.35

Results

Literature search results

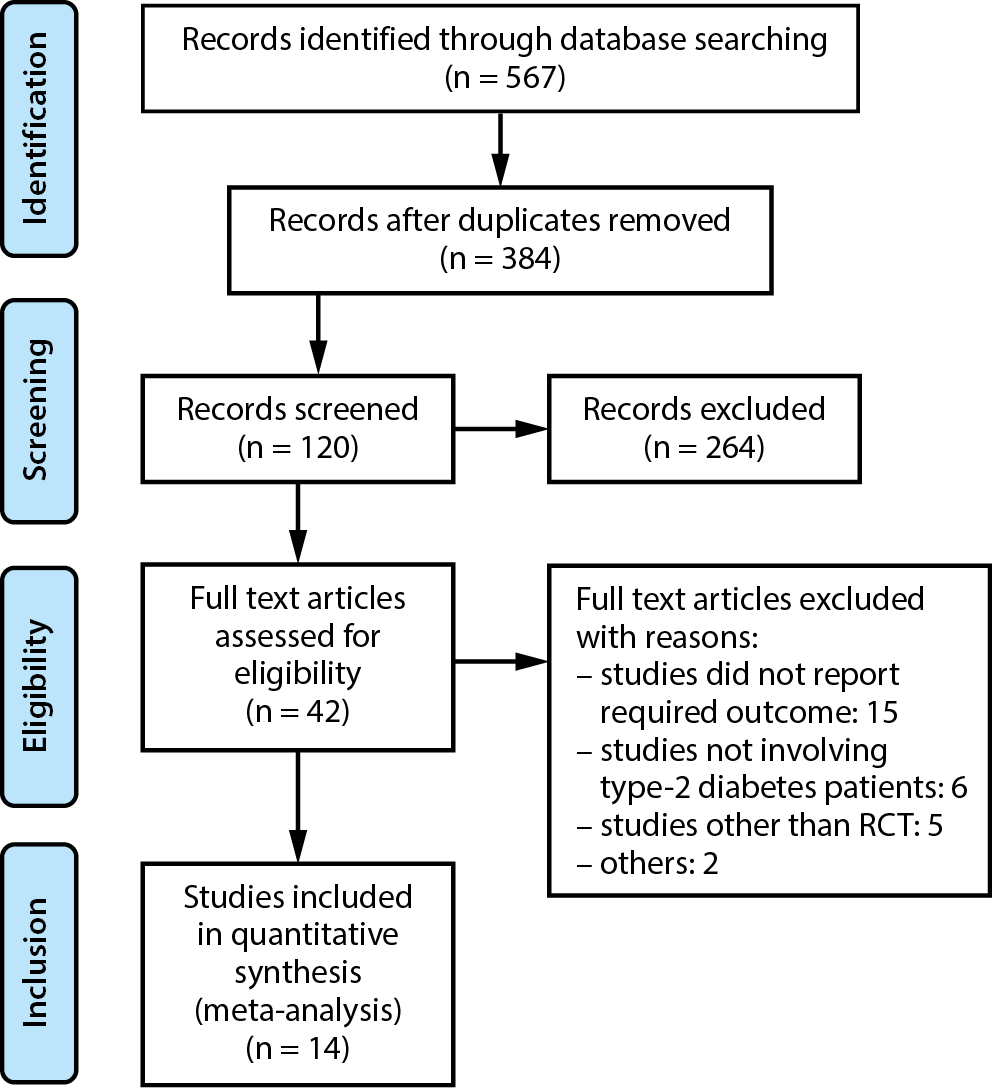

Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA chart for the study selection process. A total of 567 studies were retrieved through a comprehensive search of online databases. After eliminating duplicates, the abstracts and titles of 384 studies were screened. Only 120 studies qualified for full-text evaluation. Fourteen publications were ultimately included based on the PICOS criteria36 presented in Table 1. The characteristics of all included trials are displayed in Table 2. The included studies evaluated the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation on glycemic index, HbA1c level and insulin sensitivity in individuals with T2DM. In all the included investigations, the median follow-up time ranged from 3 to 36 months.

Risk of bias and publication bias

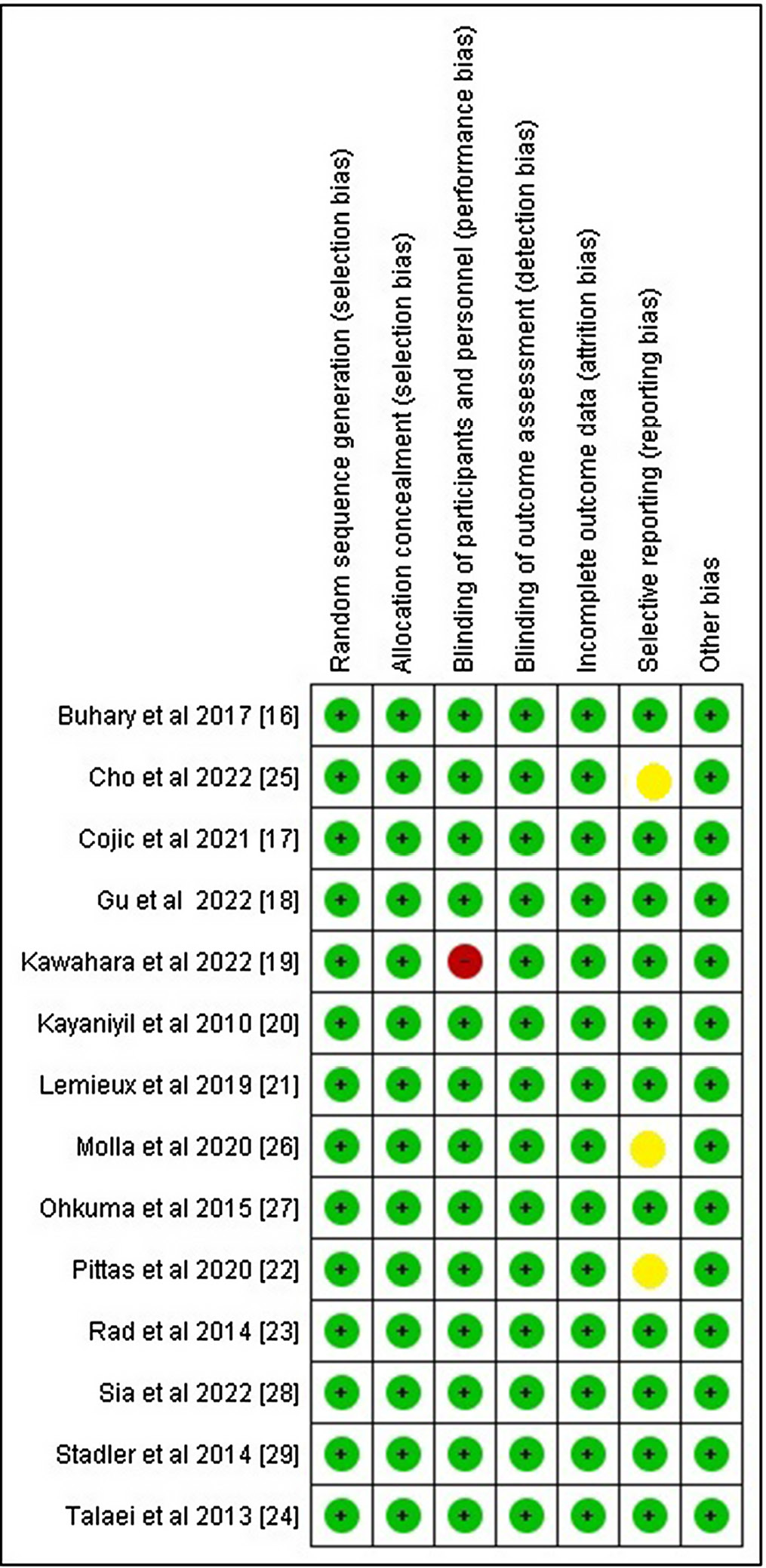

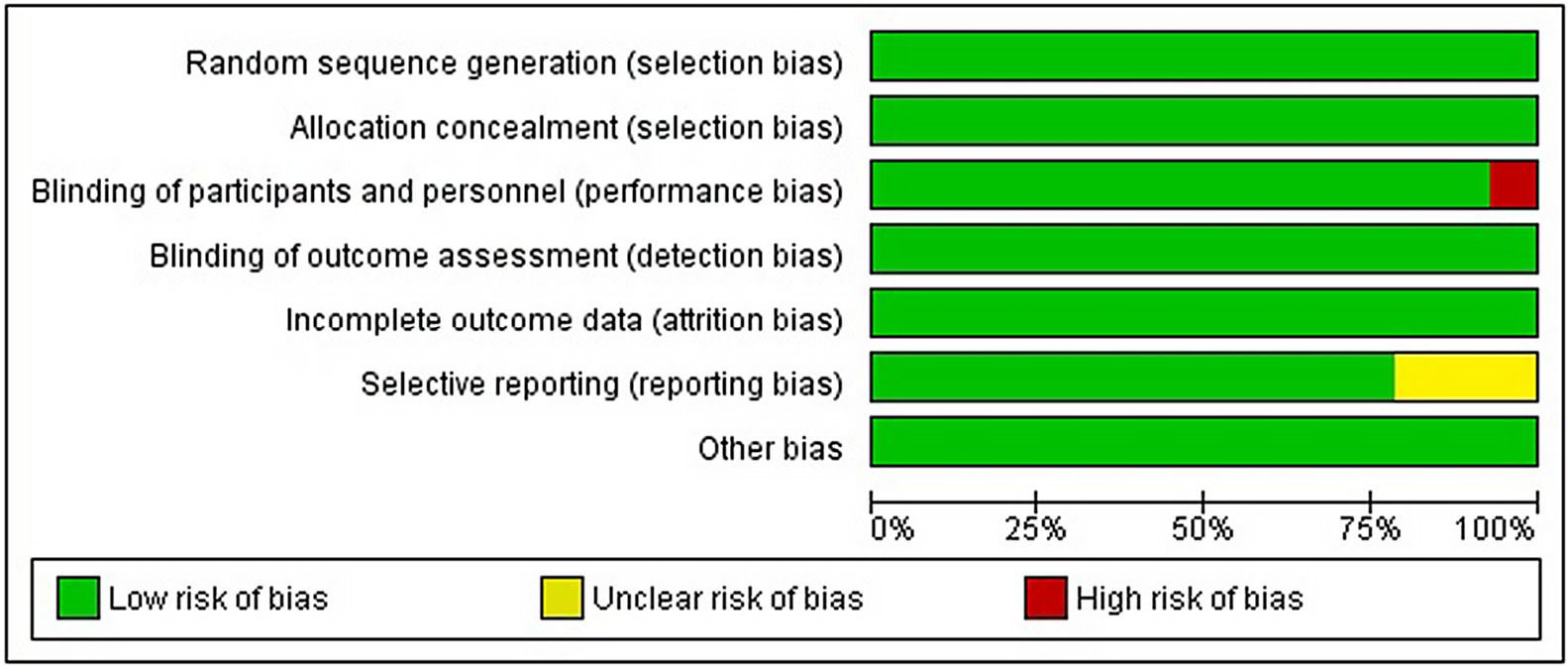

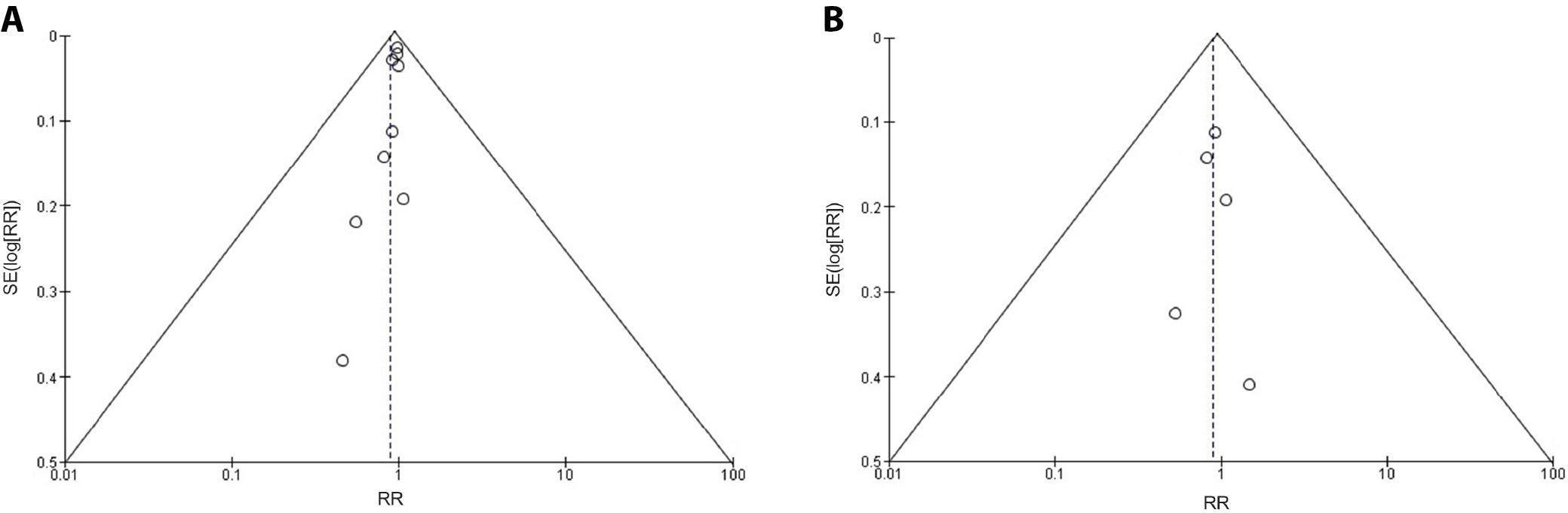

The quality of the included studies was assessed, as shown in Table 3. Figure 2 depicts a summary of the risk of bias, and Figure 3 presents a risk of bias graph. Ten of the 14 included studies had a low risk of bias, whereas 3 studies had a moderate risk attributable to selective reporting or reporting bias. One study showed a high risk of performance bias. Figure 4A depicts the funnel plot for studies related to the effect of vitamin D supplementation, which indicates a low probability of publication bias, with a significant p-value of 0.394 (Begg’s test). Figure 4B depicts the funnel plot for studies related to the effect of cigarette smoking, which indicated a low probability of publication bias, with a significant p-value of 0.252 (Begg’s test).37

Efficacy outcomes

Effect of vitamin D deficiency on insulin resistance

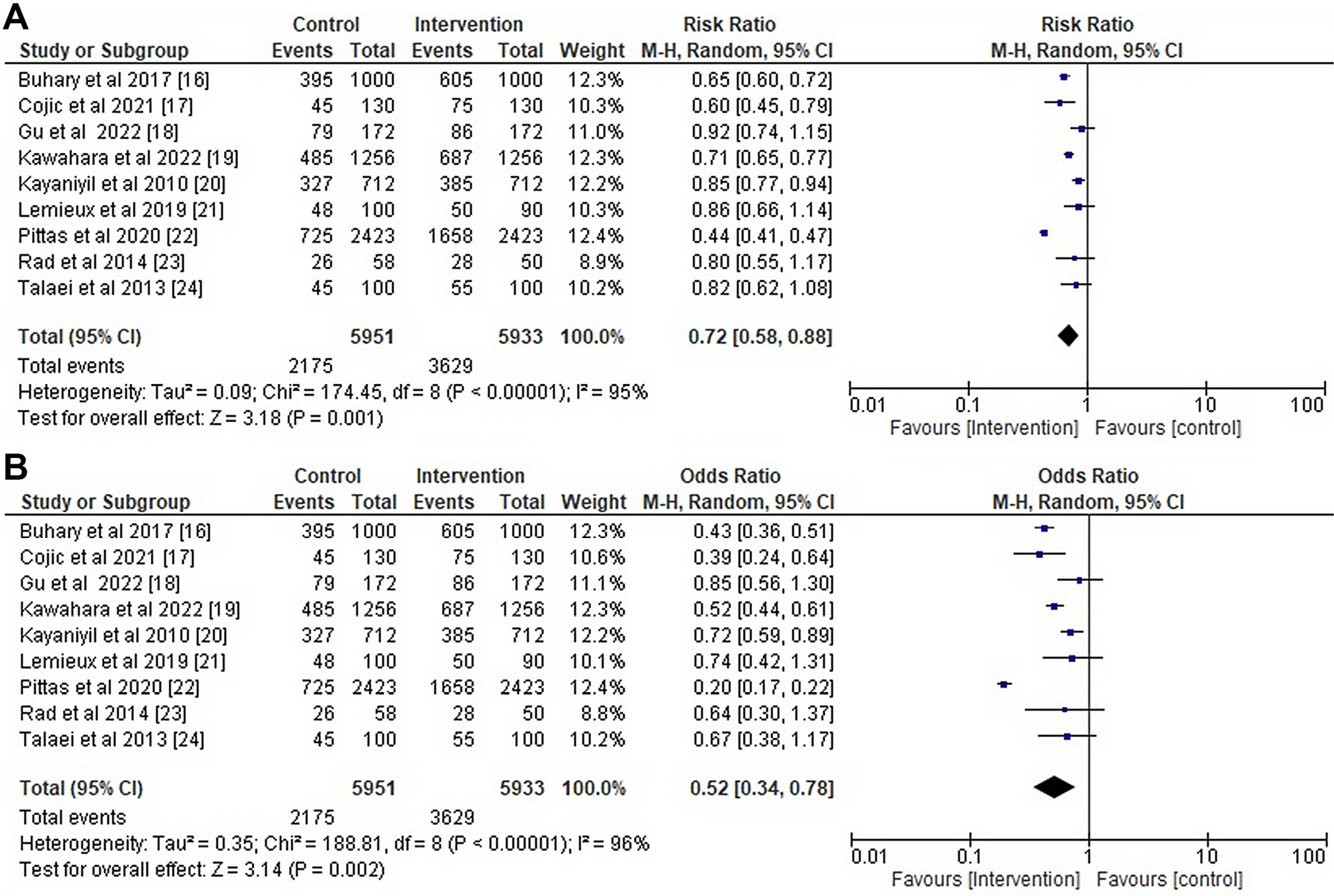

The 14 studies evaluated in this meta-analysis included a total of 23,289 individuals with T2DM. Among these, 9 studies provided information on the effect of vitamin D deficiency on insulin resistance in people with T2DM. Table 4 displays a detailed comparison of the intervention and control groups with respect to the main outcome, comparative BMI values, and changes in HbA1c and vitamin D levels due to vitamin D supplementation. The values presented in Figure 5 show a substantial change in the intervention group, with a RR of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.58, 0.88; p = 0.001), high heterogeneity value for risk ratio of 95%, an odds ratio (OR) of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.78; p = 0.002), and high heterogeneity value for odds ratio of 96%.

Effect of smoking cessation on glycemic index

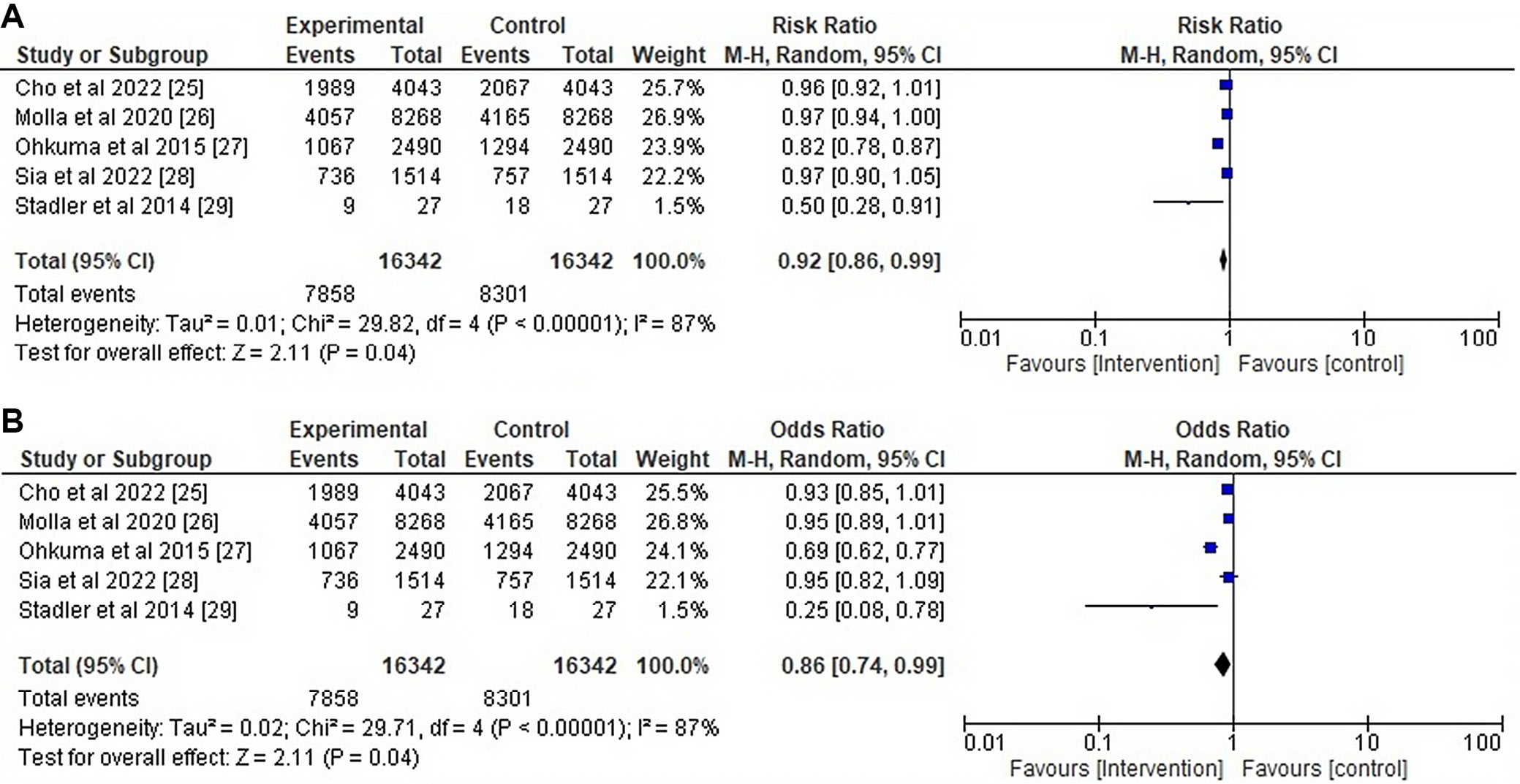

The remaining 5 studies provided information on the effect of cigarette smoking on glycemic index in people with T2DM. Table 5 displays a detailed comparison of the intervention and control groups with respect to the main outcomes, BMI of the control (non-smokers) and smoker groups, and changes in HbA1c level due to smoking cessation. As in the case of vitamin D supplementation, the meta-analysis data show a substantial change in the intervention group, with a RR of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.99; p = 0.04) and an OR of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.74, 0.99; p = 0.04); there was high heterogeneity of 87% (Figure 6).

Risk ratio values and OR values lower than 1 indicate a high likelihood of the positive effect of vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation on improving the glycemic index (HbA1c level) and insulin sensitivity in individuals with T2DM. High heterogeneity was detected among the pooled studies (I2 > 85%).

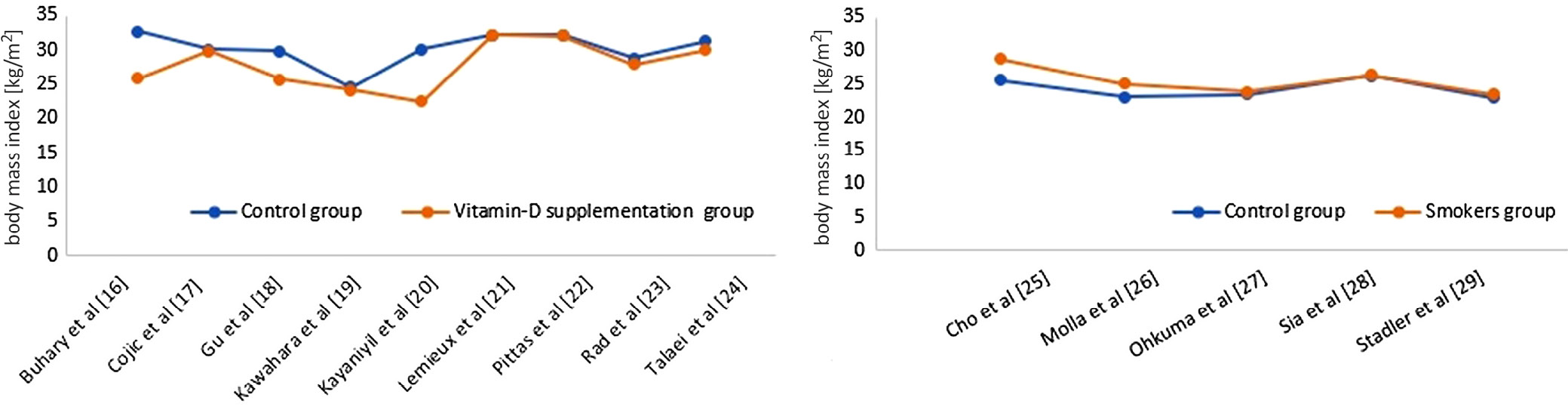

Figure 7 presents a comparison of BMI for the control and vitamin D supplementation groups and the control (non-smoker) and smoker groups. Vitamin D supplementation reduces BMI values, while smoking increases BMI and obesity when compared to the control group.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis designed to investigate the glycemic control outcomes in persons with T2DM, we discovered that vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation decreased plasma HbA1c and insulin resistance. Additionally, we observed that vitamin D supplementation lowered BMI compared to the control group, which is consistent with the findings of other studies,38, 39 showing that vitamin D-deficient individuals have a higher BMI but experience a decrease in BMI after taking a reasonable amount of vitamin D supplements. Similar to other studies40, 41 that demonstrated that smoking increases BMI and obesity, our research revealed that smoking raises BMI in comparison to the control group. Hemoglobin undergoes constant, gradual, non-enzymatic glycosylation due to hyperglycemia.42 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study established that HbA1c is the gold standard for assessing glycemic control in diabetes management.43 George et al.44 conducted a meta-analysis to assess the influence of vitamin D on glycemic management and insulin resistance. The authors reported a slight reduction in fasting blood glucose and insulin resistance, but no improvement in HbA1c levels. We found that vitamin D treatment decreased the elevated plasma HbA1c levels, indicating that vitamin D is advantageous for preventing or delaying the onset of diabetic complications. These disparate outcomes may be the result of our inclusion of a higher number of recent investigations. There was a substantial positive link between HOMA-IR and the development of T2DM. The HOMA-IR is an important factor in the onset of diabetes.45, 46 Insulin resistance is defined as a decreased sensitivity of insulin target tissues to insulin, and the majority of T2DM patients have mixed insulin resistance.47 Frequently, blood glucose concentration and insulin secretion are indirect indicators of insulin sensitivity. In T2DM patients, the blood glucose has not been well managed, which triggered β-cells to produce even more insulin.48, 49 In the vitamin D treatment group, insulin and HOMA-IR values significantly decreased. Insulin secretion is a calcium-dependent mechanism. Vitamin D activates L-type calcium channels on islet beta cells, which modulate calcium levels, initiate insulin signaling and stimulate insulin release.50 Vitamin D deficiency can be accompanied by a drop in plasma calcium concentration, which in turn induces a secondary increase in calcium levels, altering insulin signal transduction, interfering with insulin release and disturbing islet beta-cell function.51 Therefore, the present study further validates these results and demonstrates that vitamin D supplementation improves insulin resistance in individuals with T2DM in the short term.

Smoking is associated with the early onset of microvascular disorders and may contribute to the pathogenesis of T2DM.52, 53 Both the transition from normal glycemia to impaired glucose tolerance and the increased risk of developing diabetes are predicted by smoking.54, 55 According to the studies by Akter et al.56 and Campagna et al.,57 smoking cessation can reduce the risk of macrovascular problems and significantly improve the glycemic index. This meta-analysis demonstrated a substantial association between smoking cessation and a drop in HbA1c level as well as an improvement in glycemic index, similar to the previous findings.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Even though it was completed with the recommended methodological rigor, its results are limited by the availability of only 14 RCTs with moderate to high heterogeneity. In addition, few long-term follow-up studies were included, and the effects of vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation on insulin secretion were not considered. Even if the heterogeneity of the literature was avoided, heterogeneity was still present due to the dose variability of vitamin D intake in the included studies and variable smoking cessation periods. In addition, the RR values were generally applied to establish the association between the two parameters, which may introduce bias when comparing the outcomes of RCTs of varied durations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, both vitamin D supplementation and smoking cessation are associated with a moderate decline in BMI and an improvement in insulin sensitivity in people with T2DM.