Abstract

Background. Adjuvant therapy after surgery is effective for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer (GC), but the regimens are not uniform, resulting in imbalanced benefits.

Objectives. To compare the overall survival (OS), relapse-free survival (RFS) and disease-free survival (DFS) of patients with local-advanced GC (LAGC) after surgery plus adjuvant therapy and with surgery alone based on meta-analysis.

Materials and methods. Literature search was performed among the articles published in the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library databases from January 2000 to December 2018. Study selection was conducted based on the following criteria: randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on surgery plus adjuvant therapy compared to surgery alone; studies compared OS and/or RFS/DFS; and cases medically confirmed with LAGC. Only articles in English were included.

Results. A total of 12 datasets from 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 4606 patients were included in the meta-analysis. There was a significant improvement in OS of patients who underwent postoperative adjuvant therapy (HR 0.78; 95% CI: 0.72–0.84; p < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, it showed a higher improvement in OS patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy plus immunotherapy or radiotherapy (HR 0.72; 95% CI: 0.61–0.85; p < 0.001).

Conclusions. Adjuvant therapy led to survival benefits in patients with LAGC.

Key words: chemotherapy, gastric cancer, radiotherapy, overall survival

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) ranks as the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally.1 As revealed in GLOBOCAN 2012, the incidence of GC in East Asia populations is the highest.2 Most patients are at an advanced stage at diagnosis, and surgery is their only chance of survival. In recent years, significant advances have been made in surgical techniques, and surgical concepts have been continuously updated. Although surgery for different extents of lymph node dissection, especially D2 lymphadenectomy, is well accepted as a standard for locally advanced GC (LAGC),3 many patients still present local-regional recurrence and distant metastasis. On this basis, the efficacy of single radical surgery for LAGC is not sufficient.

In the past decades, there have been many explorations into the treatment of LAGC, including preoperative neoadjuvant radiotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and combined immunotherapy. These treatment options can reduce the stage of tumor regression and eliminate micrometastases before surgery, thereby improving the R0 resection rate and reducing intraoperative spread and the recurrence rate. These indeed prolong patient survival. Although these studies4, 5, 6 have confirmed the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant therapy in LAGC, there is still no treatment standard.

Postoperative chemotherapy has been considered an option for LAGC. Among these regimens, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy combined with platinum and/or docetaxel is regarded as the standard.7 In the previous meta-analysis, postoperative chemotherapy contributed to the extension of overall survival (OS) in LAGC after radical surgery.8 In recent decades, several large-scale trials have continuously updated their data on treatment efficiency, such as CLASSIC9 and ACTS-GC.10 In recent years, with the development of radiation therapy and the gradual application of immunotherapy, many patients can benefit from radiotherapy and chemotherapy or combined immunotherapy. Meanwhile, other strategies (e.g., radiotherapy or immunotherapy) have been adopted for treating LAGC. However, the results of many studies are inconsistent, and there are disputes over therapeutic applications.

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effects of postoperative treatment on the prognosis of LAGC patients, especially those receiving chemotherapy plus radiotherapy or immunotherapy. This meta-analysis was designed to compare the OS, relapse-free survival (RFS), and disease-free survival (DFS) of patients with LAGC after surgery plus adjuvant therapy and those with surgery alone.

Materials and methods

Study design

Based on the guidelines of meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), a protocol was designed by our team, including a search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, primary and secondary outcomes, and statistical analysis. The study is consistent with the requirements of PRISMA and a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR).

Criteria of eligibility

Two authors (WZ and DLH) independently searched articles published in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library between January 2000 and December 2018. The terms utilized included “gastric carcinoma”, or “adenocarcinoma of the stomach”, or “gastric cancer”, or “stomach tumors” and “radiotherapy”, or “radiation therapy”, or “chemotherapy”, or “external irradiation therapy”, or “adjuvant chemotherapy”, or “external radiation therapy”. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English were included in this meta-analysis. The eligible studies should have met the following criteria: 1) involving patients histologically confirmed with advanced GC; 2) RCTs reporting the comparison between adjuvant therapy after radical surgery or surgery alone; 3) Reporting the hazard ratio (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for OS and RFS/DFS.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each eligible study: first author, study design, country, year of publication, patient age, number of patients (with/without postoperative adjuvant therapy), median survival, and HR of OS and/or RFS/DFS. In cases of missing data, we contacted the authors by e-mail to obtain the information. A comprehensive discussion was held among all investigators until reaching a consensus when there were any disputes on the data collection.

Hazard ratio was used to analyze the time-to-event data, including OS and RFS/DFS. The method by Tierney et al. was used to calculate the HR if it was not mentioned in the extracted articles.11

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated using the domain-based Cochrane Collaboration’s tool as previously described.12 Funnel plots were constructed to assess the risk of publication bias across the series for all outcome measures.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test Q-statistics evaluated the heterogeneity, and the degree of heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 statistic. A random effects model was selected when p < 0.10 or the I2 statistic was >50%. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was adopted. For the sensitivity analysis, we recalculated the pooled statistics after deleting the related study. Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 5.3; Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for the statistical analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the eligible studies

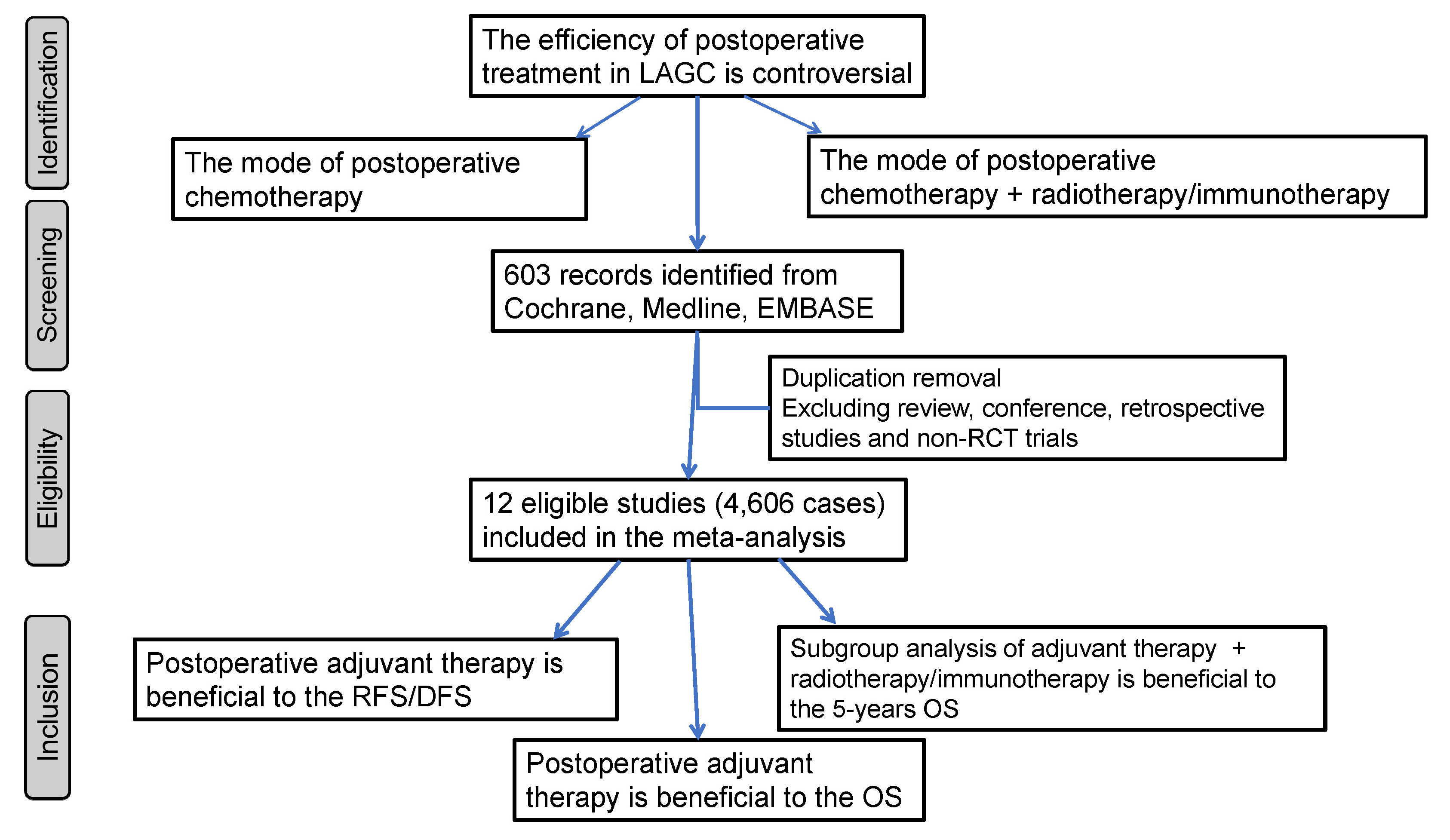

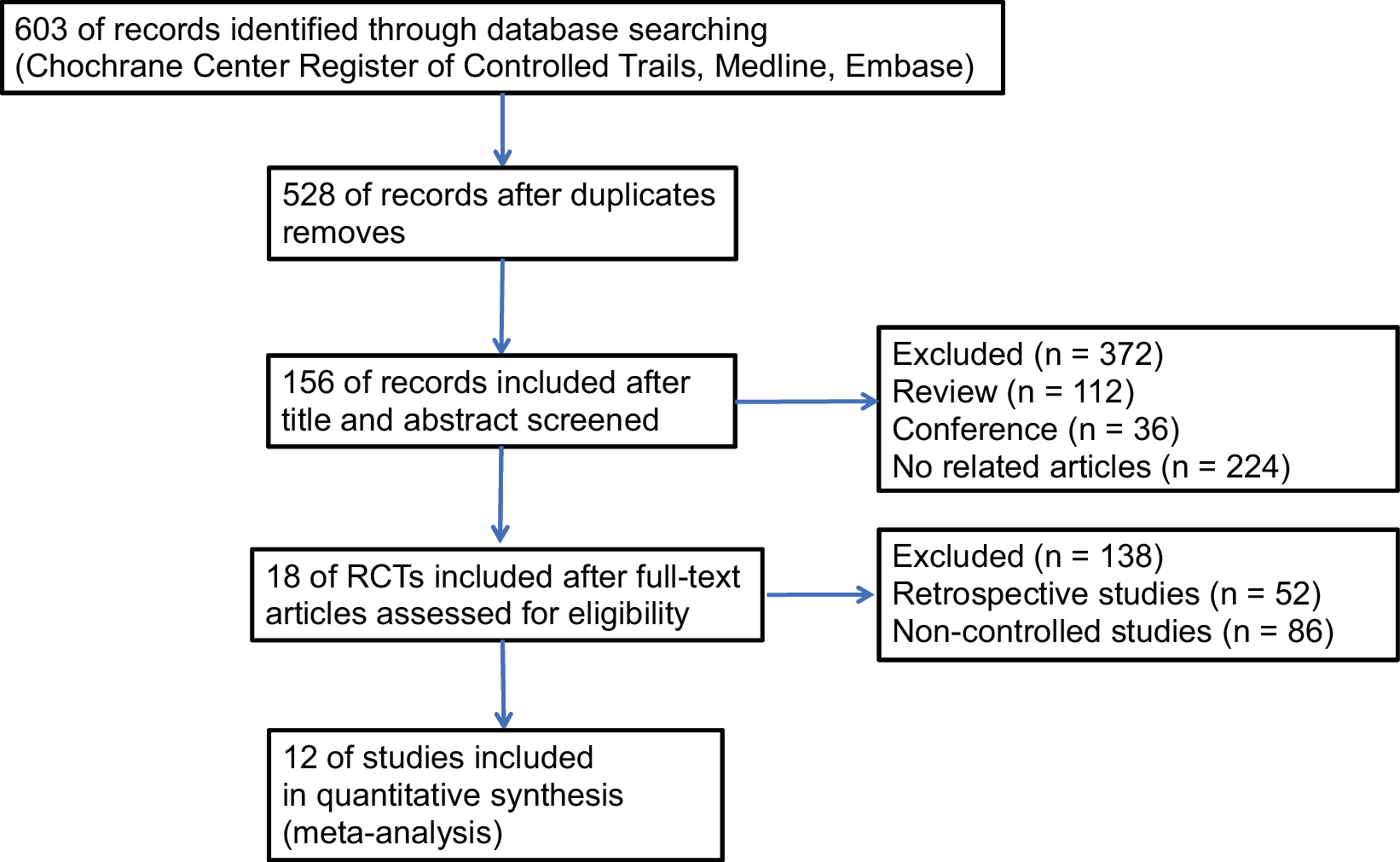

Figure 1 shows the literature selection and screening flowchart, which resulted in 18 RCTs9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 enrolling 7,919 patients into the meta-analysis. The basic characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1. In brief, the studies were published from 2001 to 2018, and the sample sizes ranged from 137 to 1,059 people. Six studies used 3 datasets, which were updated using 3 RCTs, and only 3 studies were included. Four studies were excluded as the HR could not be extracted due to the absence of OS, PFS, or DFS.13, 14, 15, 16 Two datasets were selected from the 3-arm study.17

A total of 12 datasets were obtained from the RCTs comparing the OS of GC patients with or without postoperative therapy.9, 10, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27 All RCTs had undergone peer-review between 2001 and 2014. Herein, 3 trials were from Japan, South Korea, and China, respectively, 2 from France, 4 from Italy, 1 from Poland, and 1 from the USA. A total of 4,606 patients were included in the analysis, among which 2319 received postoperative therapy, and 2,287 underwent radical surgery.

The disease-stage classification of LAGC patients was mainly performed based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system, together with the classification system recommended by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA). Patients with at least a 70% lymph node-positive rate were recruited in 1 study.18 In addition, patients with N+ tumors with at least an 80% lymph node-positive rate were recruited in 7 studies.9, 10, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24 Three trials recruited patients with N+ tumors with a lymph node-positive rate of 100%.17, 22, 27 Meanwhile, D2 lymphadenectomy was performed in 4 trials9, 10, 22, 27 and D1-plus and R0 resection was performed in 6 trials.9, 10, 18, 21, 22, 27

OS determination

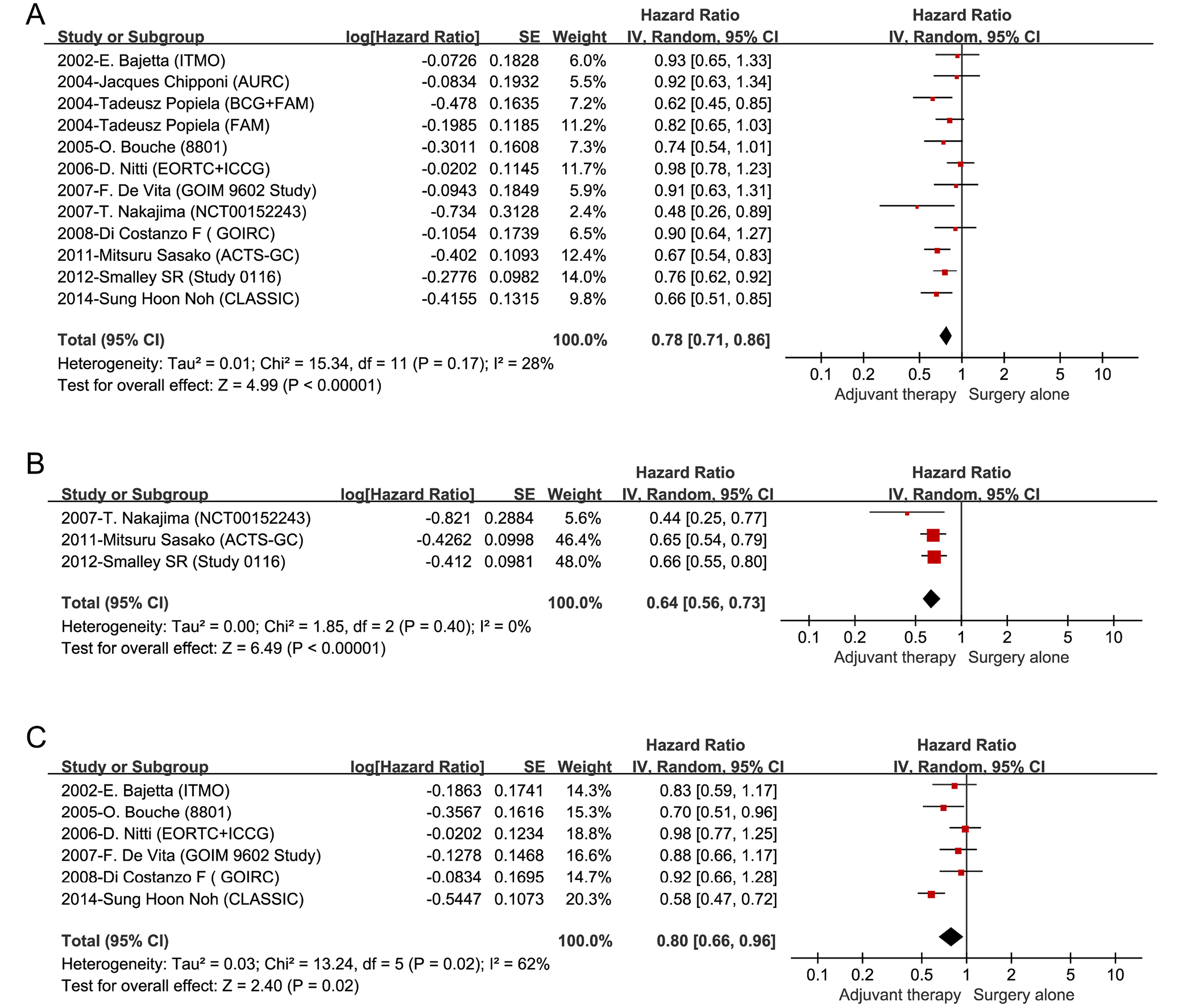

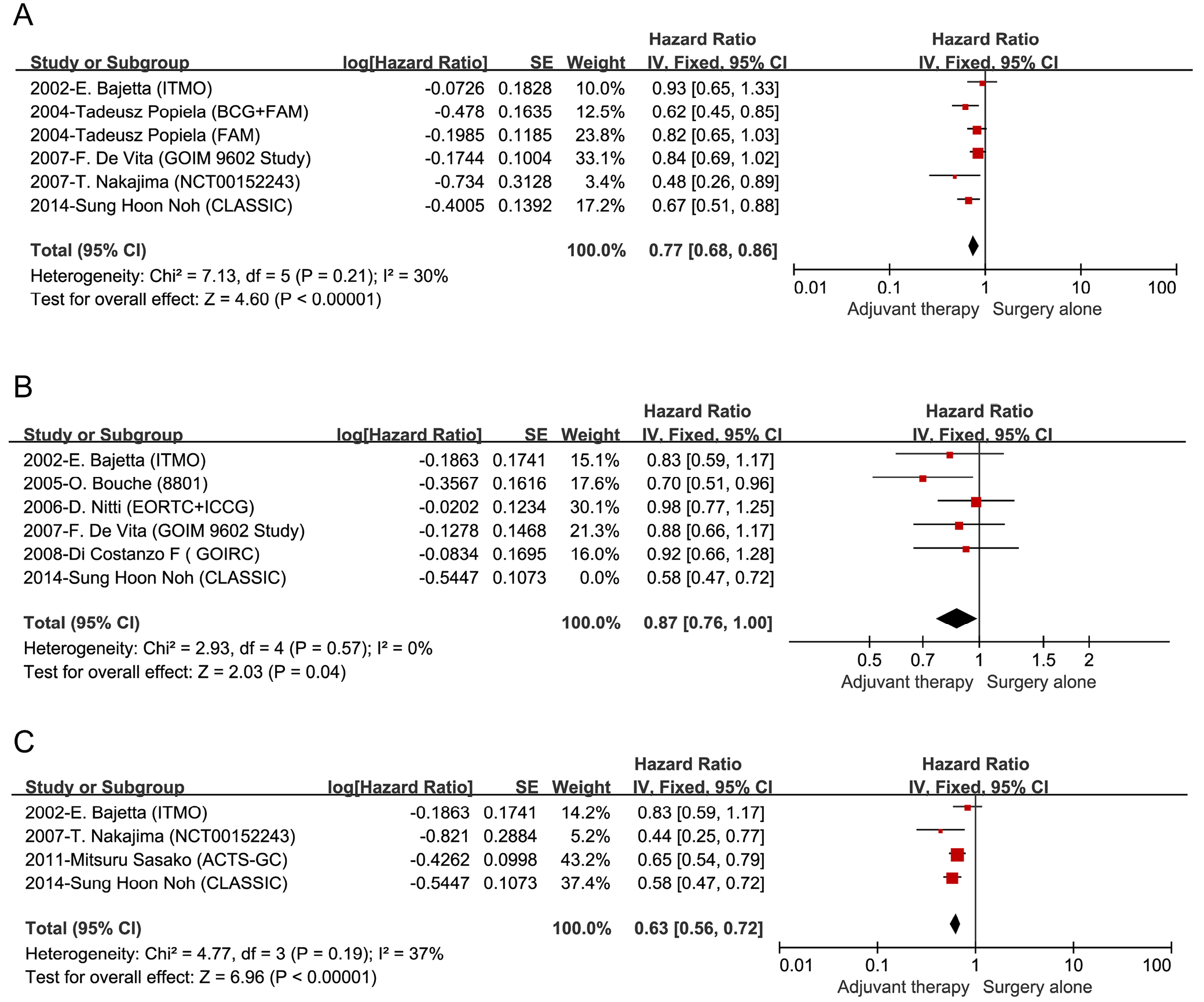

All patients were followed up for more than 5 years. The OS rates were higher in most of adjuvant therapy groups than those of the surgery group in 5 of 11 trials9, 10, 17, 22, 24 (Figure 2A). We present the pooled OS data in Supplementary Fig. 1. In the study by Nitti et al.,21 2 datasets from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial and the International Collaborative Cancer Group (ICCG) were collected to be analyzed jointly. The OS rate in the adjuvant therapy group was higher than that in the surgery group in the EORTC trial.21 However, in the ICCG trial, the OS rate of patients receiving adjuvant therapy was lower than that of surgery-only cases.21

RFS

Three RCTs reported the RFS with no heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 0%).10, 22, 24 Significant differences were observed between the patients receiving adjuvant therapy and those receiving just surgery (HR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.56–0.73; I2 = 0%; Figure 2B). We present the pooled RFS data in Supplementary Fig. 2.

DFS

Heterogeneity was observed in the DFS of 6 RCTs (p = 0.02; I2 = 62%).9, 18, 20, 21, 23, 27 On this basis, the random-effects model was used, which indicated significant differences in DFS between the patients receiving adjuvant therapy and those only receiving surgery (HR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.66–0.96; p = 0.02; I2 = 62%). There was no heterogeneity for these studies after omitting 1 study9 (I2 = 0%; Figure 2C). We present the pooled DFS data in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis

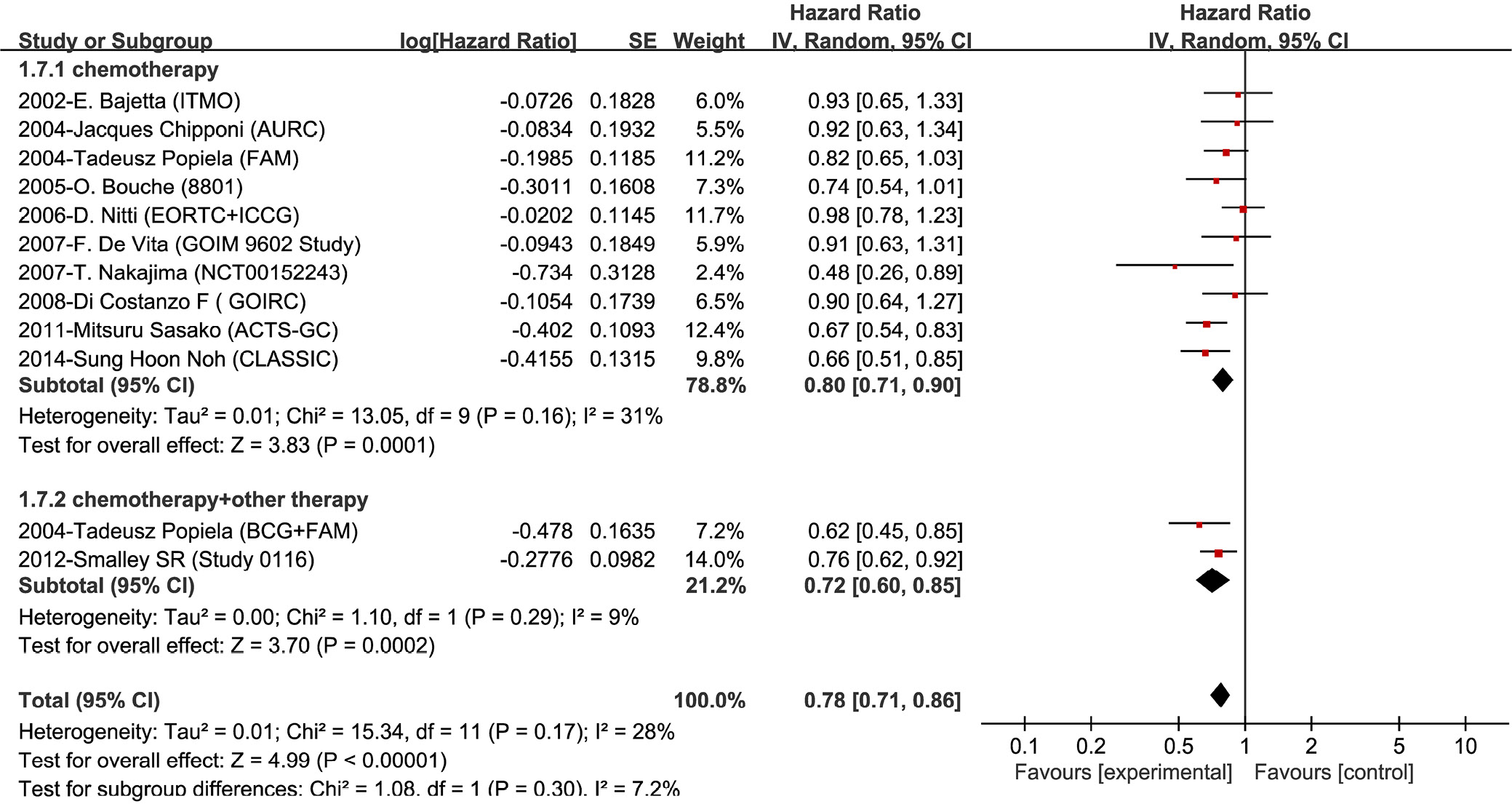

In addition to chemotherapy, we divided the 12 sets of data into 2 subgroups based on the combination of other adjuvant therapies (i.e., radiotherapy or immunotherapy). Subgroup analysis indicated that patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy plus radiotherapy or immunotherapy presented a significant increase in 5-year OS rate than those only receiving chemotherapy (HR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.60–0.85; p < 0.001; Figure 3).

Different postoperative adjuvant regimens may affect the prognosis

All patients enrolled in the RCTs received chemotherapy with different regimens, with all studies applying 5-FU except for 1 study9 using capecitabine and oxaliplatin. Two studies involved the oral administration of fluorouracil agents, such as S-1 and tegafur–uracil (UFT).10, 22 The rest of the regimens were carried out by iv. infusion of 5-FU. Among the included studies, 1 involved immunotherapy using the bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG),17 and 1 involved radiotherapy.24 The data supported that adjuvant chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy or immunotherapy contributed to the extension of OS (Figure 3). The outcomes of OS for the patients with lymphatic metastasis are shown in Figure 4.

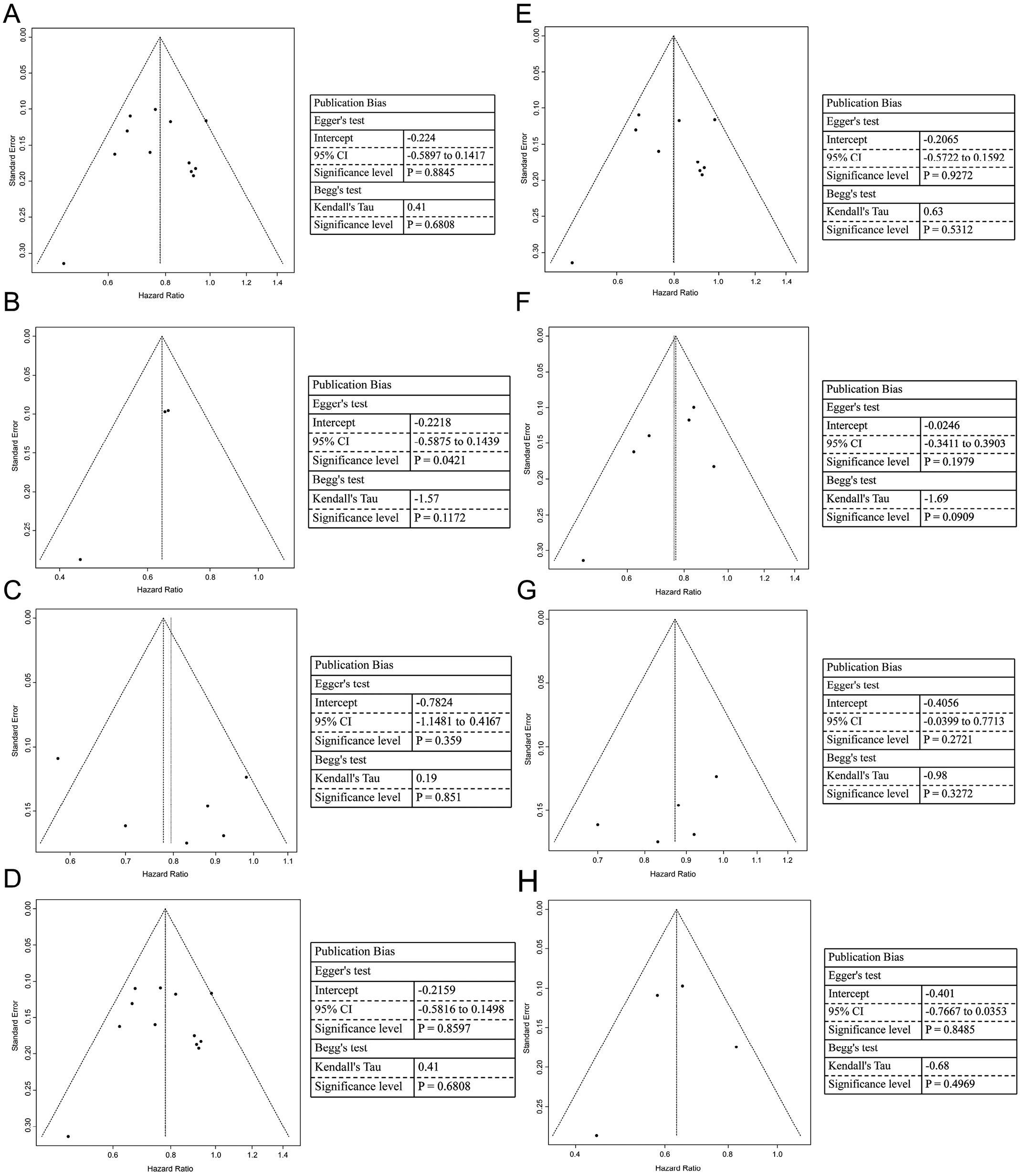

Publication bias

As shown in Figure 5, together with the Egger’s and Begg’s tests, the publication bias in these studies was low. Egger’s regression test determined the degree of asymmetry in the funnel plot by measuring the intercept of a standard normal regression that deviated from precision. The Begg’s rank correlation test explained the correlation between the rank of the effect size and its variance. A p-value of more than 0.05 demonstrated statistical difference with a low risk of publication bias. In this study, the p-values for the Begg’s test and Egger’s test in most of the groups were more than 0.05. However, p-value for the Begg’s test in the studies listed in Figure 2B was 0.1172, and p-value for the Egger’s test was 0.0421 (Figure 5B), which may be related to the minor trials in this group. The funnel plots of 12 trials listed in Figure 2A were symmetric, and the p-values for the Begg’s test and Egger’s test were 0.885 and 0.680, respectively (Figure 5A). Meanwhile, the p-values for the Begg’s test and Egger’s test for the studies listed in Figure 2C were 0.851 and 0.359 (Figure 5C), while those for the studies listed in Figure 3 (chemotherapy and chemotherapy and other therapy) were 0.680 and 0.860 (Figure 5D), respectively. The p-values for the Begg’s test and Egger’s test for chemotherapy of the study listed in Figure 3 (chemotherapy only) were 0.531 and 0.927 (Figure 5E), while those for the studies listed in Figure 5A were 0.091 and 0.198 (Figure 5F), those listed in Figure 5B were 0.327 and 0.272 (Figure 5G), and those listed in Figure 5C were 0.497 and 0.858 (Figure 5H), respectively. These data mostly indicated a low risk of publication bias.

Discussion

The prognosis of LAGC patients is usually poor, and many present with recurrences or metastases. In recent years, immunotherapy has been reported to be effective in the treatment of multiple malignancies.29 However, the efficacy of immunotherapy alone is limited. Indeed, many studies confirmed that chemotherapy or radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy after surgery is more effective for solid tumors.30, 31, 32 This meta-analysis of 12 sets of data indicated that postoperative chemotherapy improved the prognosis of LAGC patients. Specifically, LAGC patients receiving adjuvant therapy showed an increase of about 22% in the 5-year OS rate compared to those only receiving radical surgery (Figure 2A). Although there is a lack of statistical significance upon individual analysis, the OS data of 7 trials along with the DFS data from another 4 trials indicated that postoperative chemotherapy contributed to the survival of LAGC patients, though this is probably due to the small sample size enrolled in the trials. The survival benefits after postoperative chemotherapy were significant after pooling for the meta-analysis.

Six sets of data reported the OS outcomes for patients with lymphatic metastasis (Figure 4A). The analysis of patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy showed increased OS by up to 23%. However, 3 trials supported postoperative therapy with no statistically significant trends. Two RCTs mainly recruited patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, or IV (T4N1M0).17, 27 Likewise, in another study,18 the ratio of patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, or IV (T4N1M0) exceeded 80% of all enrolled patients.

Nine studies considered RFS or DFS as their primary endpoint. Three RCTs compared the RFS of LAGC patients with and without postoperative chemotherapy,10, 22, 24 which indicated the survival benefits of postoperative chemotherapy. The pooled HR was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.56–0.73) after combining all the HRs in the selected trials, which significantly favored postoperative chemotherapy (p < 0.001, Figure 2B). Six RCTs compared the DFS of GC patients receiving postoperative treatment compared with those who received no postoperative treatment.9, 18, 20, 21, 23, 27 Almost all trials favored postoperative treatment except for 4 trials showing no statistical differences.18, 21, 23, 27 When considering the study of Noh et al.,9 survival benefits were observed after postoperative therapy (HR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.66–0.96; p = 0.02) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 62%; Figure 2C). Upon removing the study, the survival benefits were significantly weaker (HR = 0.87; 95% CI: 0.76–1.0; p = 0.04) with a low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; Figure 4B). The high heterogeneity was mainly associated with higher weight and better survival benefits. In the study by Noh et al., 1,035 patients underwent curative D2 gastrectomy with no macroscopic or microscopic evidence of tumors. The radical surgical treatment produced a significant survival benefit, and the high heterogeneity might also be caused by the treatment design, including the chemotherapy regimen, the number of patients, and the surgeon’s skills.

Four studies reported the outcomes of OS and RFS for patients who underwent D2 gastrectomy, with no evidence of remaining tumors noticed among these patients (Figure 4C). The OS and RFS outcomes were consistent in the patients receiving combined therapy (OS: HR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.58–0.83; p < 0.001; RFS: HR = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.53–0.76; p < 0.001). Patients enrolled in the Japanese trials showed higher postoperative survival rates than in trials carried out in Western Europe and the USA.8 Three trials were carried out in Japan, and the results showed statistically significant trends to support postoperative therapy. There was no statistical significance in the study by Bajetta et al.,27 which was probably due to the advanced stage of the eligible patients.

Several studies reported that 40–60% of GC patients undergoing radical surgery at stage II or III showed a loco-regional recurrence before postoperative therapy. Loco-regional failure often occurred in the anastomosis, followed by the stomach bed and undissected regional nodes. Radiotherapy could improve postoperative local control of GC, but there were some disputes on survival in the data from randomized trials. D2 loco-regional node resection was the standard method, and postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) combined with chemotherapy was still controversial for treating LAGC.33 In this meta-analysis, 2 studies confirmed that LAGC patients showed longer OS after PORT combined with chemotherapy. In 2018, a network meta-analysis confirmed that the 5-year OS rate and the 2-year PFS of patients receiving chemoradiotherapy were higher than those only receiving surgery (HR = 0.80 and 0.58, respectively).8 However, the 5-year OS rate of patients who underwent PORT was poor, indicating that postoperative chemotherapy is important for advanced GC.

In this meta-analysis, there was a higher improvement in OS among patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy plus immunotherapy or radiotherapy. Recently, malignant tumors have been confirmed to be immunogenic, and accumulating evidence demonstrates a potential link between cancer progression and anti-tumor immunity.34 In 2018, a meta-analysis confirmed that chemotherapy combined with cytokine-induced killer cell (CIK)/dendritic cell-CIK (CIK/DC-CIK) therapy after surgery significantly increased OS rates (HR = 0.712; 95% CI: 0.594–0.854), DFS rates (HR = 0.66; 95% CI: 0.546–0.797), and T-lymphocyte responses in patients with GC.35 In addition, a retrospective study reported a similar conclusion in epithelial ovarian cancer patients.34 Another study confirmed that the immunotherapy group presented a higher 3-year OS rate and 5-year OS rate, respectively.29 Meanwhile, patients receiving 3 or more cycles of immunotherapy showed a higher 5-year OS rate than those who received 2 cycles or less (82.10% compared to 69.90%; p = 0.035).29

A study based on the National Cancer Database (NCDB) concluded that PORT conferred an additional OS advantage, which was higher than that of adjuvant chemotherapy alone for complete resection of N2 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).36 Similarly, another study reported that PORT was associated with improved OS in patients with incompletely resected stage II or III N0-2 NSCLC.37 However, studies on PORT combined with immunotherapy are still limited for LAGC, and more clinical studies reporting the outcomes of LAGC are expected in the future.

Limitations

Indeed, there are limitations in this meta-analysis. First, the study designs of the trials differed. For example, the chemotherapy regimens and cycles were not totally consistent. Second, we only focused on the influence of postoperative treatment rather than complications and adverse effects, which may exaggerate the benefits of postoperative treatment. Finally, we could not eliminate the potential publication bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, postoperative treatment plays a significant role in improving survival in patients with LAGC. We found that patients receiving adjuvant therapy after surgery showed a significant improvement in OS. Meanwhile, patients presented a higher improvement in OS after adjuvant chemotherapy plus immunotherapy or radiotherapy.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8294045. The package consists of the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Pooled data of OS including 11 RCTs.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Pooled data of RFS including 3 RCTs.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Pooled data of DFS including 6 RCTs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.