Abstract

Background. Intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide are common emergency treatments for adult patients with migraine headaches. The comparison between ketorolac and metoclopramide for migraine treatment is an intriguing issue for research and clinical practice.

Objectives. To provide an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to help determine which treatment has better effects for migraine patients.

Materials and methods. Intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide were compared to evaluate whether intravenous ketorolac is associated with significant benefits for pain intensity, short-term headache relief and sustained headache relief among adult patients with migraines. Adverse effects were also analyzed. Five studies with a total of 674 adult patients were included in the analysis, which focused on the outcomes of pain intensity, short-term headache relief, sustained headache relief, and adverse effects.

Results. The meta-analysis showed that the only modest but statistically significant difference was present in short-term headache relief when comparing intravenous ketorolac with intravenous metoclopramide. There were no significant differences between intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide in terms of pain intensity, sustained headache relief or adverse effects.

Conclusions. The results suggest that there are no significant differences in most treatment effects (aside from short-term headache relief) and adverse effects when comparing intravenous ketorolac with intravenous metoclopramide. However, the paucity of literature on this topic might have limited the interpretation of the current results. Thus, more relevant studies are warranted.

Key words: meta-analysis, metoclopramide, migraine, intravenous, ketorolac

Introduction

Migraine is a widespread neurological disease that may be debilitating, especially for young adults and women. Research has suggested that 1.04 billion people suffer from migraine headaches globally. Thus, attention from researchers and clinicians is warranted for this condition.1 Various types of medications are available for treatment, including ibuprofen, triptans, ketorolac, and metoclopramide.2, 3 Ketorolac and metoclopramide are level B treatments for acute migraine attacks.3 Ketorolac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that can inhibit the cyclooxygenase enzyme and reduce the production of prostaglandins, which can inhibit nociceptors at sites of inflammation4 and reduce the severity of migraine-related pain.5 Intravenous ketorolac administration is a common clinical strategy for acute migraine attacks.

Metoclopramide is another important choice for the treatment of acute migraine headaches, and a previous meta-analysis has suggested that intravenous metoclopramide should be the primary agent for treating acute cases.6 In addition, a systematic review proposed that metoclopramide may be more effective than ketorolac in treating acute migraines.7 However, there have been few meta-analyses focusing on comparisons between intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide.

Comparative meta-analyses of these 2 agents have examined outcomes of pain intensity, ability to return to work or usual activities, the need for rescue medications, and the frequency of adverse events.8 However, they have not examined other types of outcomes, such as relief from short-term headaches or sustained headaches, as well as individual subgroups of side effects, such as drowsiness and restlessness.

Objectives

This meta-analysis was designed to evaluate updated literature regarding these unaddressed outcomes. Based on the available studies,8 we hypothesized that intravenous ketorolac might be inferior to metoclopramide in terms of these outcomes in adult patients.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and information sources

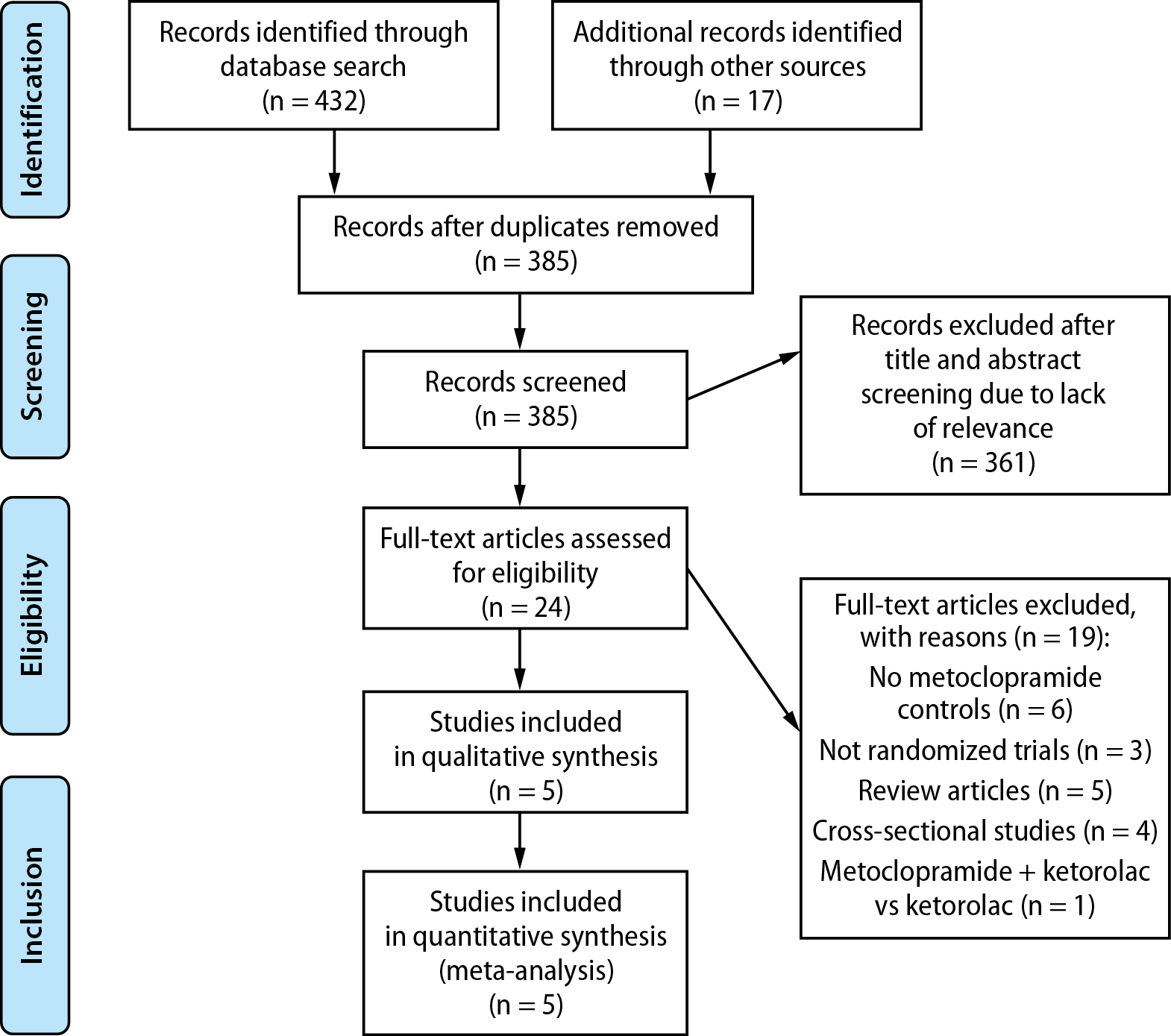

A search for relevant prospective randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was conducted using Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ScienceDirect, PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase. The following keywords have been used: “migraine”, “ketorolac”, “metoclopramide”, “pain”, “outcome”, “efficacy”, “versus”, “randomized”, “clinical”, “trials”, “controlled”, “therapy”, “treatment”, or “comparison”, “intravenous”, “headache”. The included studies were limited to those published before October 2022. The inclusion criteria for the RCTs were as follows: 1) studies comparing ketorolac and metoclopramide treatment for adult patients with migraines; 2) RCTs with baseline data and post-treatment outcomes for pain intensity, relief of short-term headaches or sustained headaches, and side effects; 3) RCTs with detailed data on the outcomes regarding pain relief and adverse events; and 4) studies published in English.

Assessment of evidence quality and data extraction

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (www.training.cochrane.org/handbook) was used as the basis for conducting the meta-analysis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines9 were used as a standard for reporting the process and results. The following data were extracted from the eligible RCTs regarding migraine patients treated with ketorolac and metoclopramide: pain intensity, the occurrence and rates of short-term headache relief and sustained headache relief, and the number of adverse events.

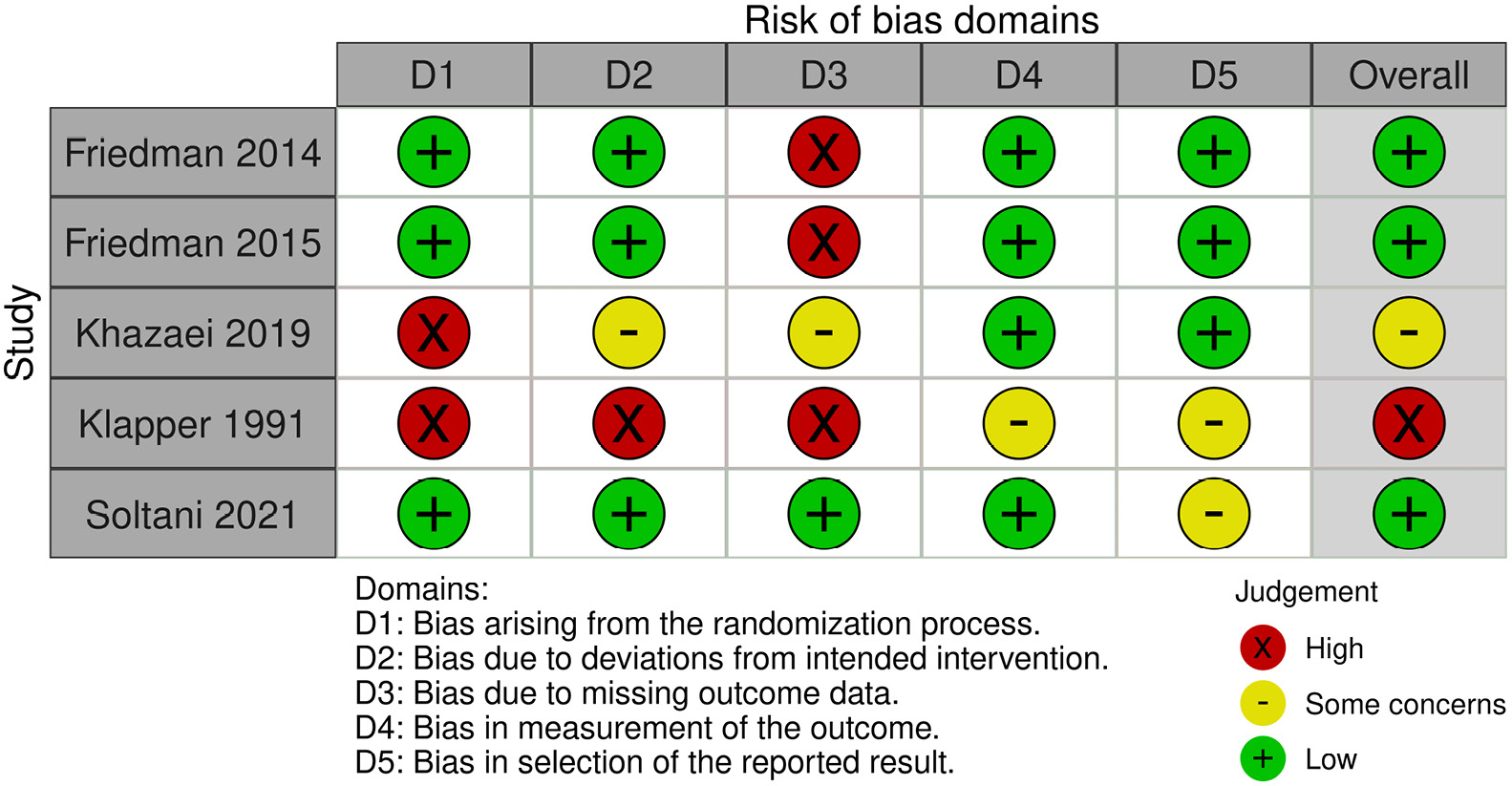

The abstracts were evaluated to screen studies, which were then independently assessed using the full text, tables and figures. The eligible studies included data on pain intensity, relief of short-term headaches or sustained headaches, and side effects. The risk of bias was evaluated according to the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement methods, and selection of the reported results (Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2), a revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials (https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool)). A collaborative review was conducted by all the authors to achieve agreement (kappa = 0.8). The final results were also reviewed by all the authors.

Meta-analysis and statistical analysis

We used the weighted mean difference to estimate numerical variables of pain intensity. Ketorolac and metoclopramide were compared to determine which medicine was better for relieving pain intensity. The overall effect size of post-treatment pain intensity was calculated as the weighted average of the inverse variance for study-specific estimates.

We generated pooled estimates of the relative risks (RRs) for short-term headache relief, sustained headache relief and adverse effects. The Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager Software Package (RevMan v. 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration, Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used. The weighted estimates of the average risks of the included studies were combined in a random-effects model. Ketorolac and metoclopramide treatments were compared to determine which treatment is more beneficial in terms of relief and side effects. The χ2 test was used to assess the heterogeneity between RCTs.10 The random-effects model was applied in the meta-analysis.

Results

Description of studies

The PRISMA selection process was followed to identify eligible studies (Figure 1), and a qualitative analysis was performed on the final 5 eligible articles that were included in the analysis.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The characteristics of these studies are presented in Table 1. An assessment of the risk of bias is illustrated in Figure 2.

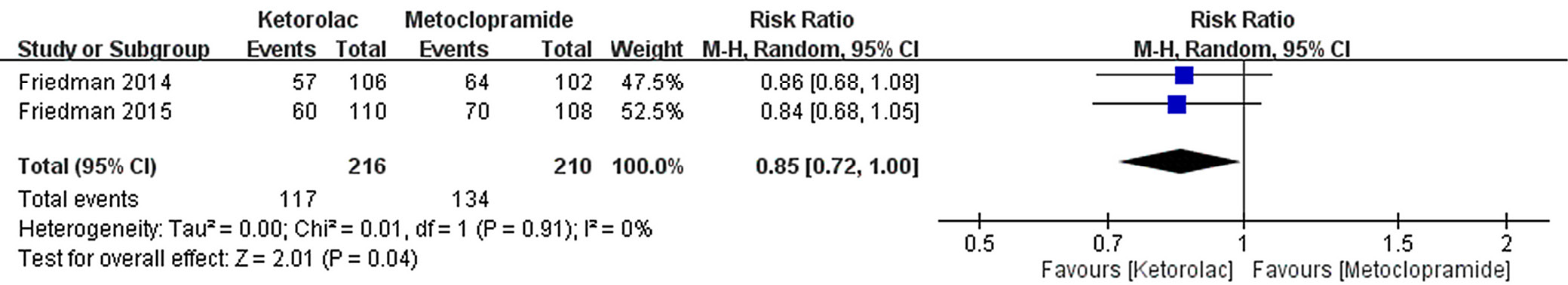

RR of short-term headache relief

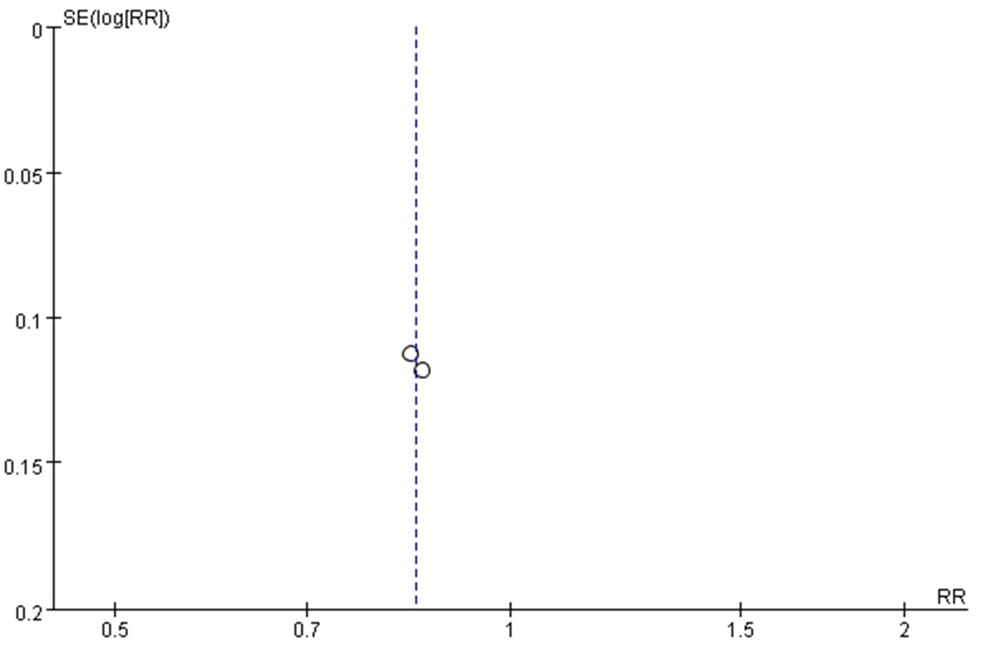

Low heterogeneity was observed. The result for the overall effect was Z = 2.01 (p = 0.04, Mantel–Haenszel method). A significant difference was observed in relative risk (RR) for short-term headache relief events between the intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide treatments (Figure 3). The funnel plot showed a symmetric distribution without significant publication bias (Figure 4).

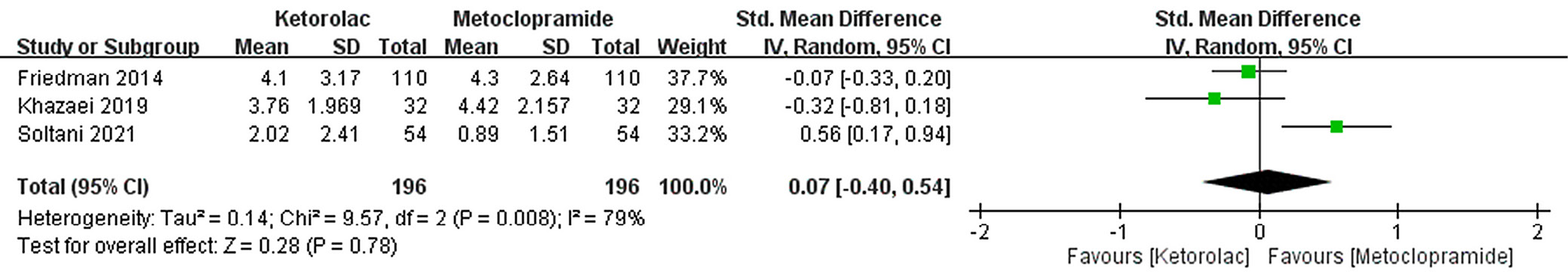

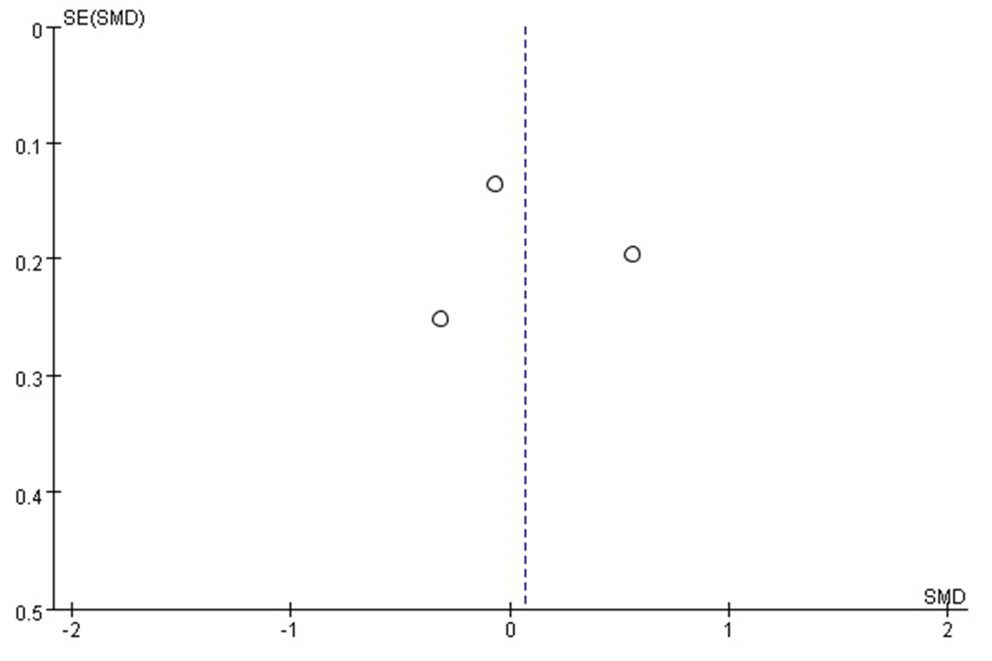

Pain intensity

The difference in pain intensity between the group of patients that received ketorolac (196 subjects) and the group that received metoclopramide (196 subjects) was 0.07 (95% confidence interval (95% CI): −0.40–0.54, inverse variance method). This suggests that the effects of ketorolac and metoclopramide treatments on pain intensity were not significantly different (Figure 5). The funnel plot showed a symmetric distribution without significant publication bias (Figure 6).

RR of sustained headache relief and adverse events

The RR of sustained headache relief was not statistically significant (test for overall effect: Z = 0.07 (p = 0.94), Mantel–Haenszel method). In addition, the RR of adverse events was not significant for ketorolac compared to metoclopramide (test for overall effect: Z = 1.15 (p = 0.25), Mantel–Haenszel method). The difference in drowsiness as an adverse event was not statistically significant (test for overall effect: Z = 0.84 (p = 0.40), Mantel–Haenszel method). Similarly, the dimensions of restlessness (test for overall effect: Z = 1.48 (p = 0.14), Mantel–Haenszel method) and high restlessness (test for overall effect: Z = 1.77 (p = 0.08), Mantel–Haenszel method) showed nonsignificant results. The forest plots, funnel plots and publication bias statistics in this section can be referred to in the supplementary data.

Discussion

Intravenous ketorolac and metoclopramide treatments were not significantly different with regard to most outcomes (pain intensity, sustained headache relief, adverse events, and side effects of drowsiness, restlessness, and high restlessness). The only significantly different outcome was short-term headache relief. However, even though the results showed that intravenous ketorolac treatment was beneficial, the risk ratio of 0.85 suggests that it might be less effective for short-term headache relief. The 95% CI (0.72–1) indicates that the results might have the potential to be statistically nonsignificant.

In summary, the meta-analysis results demonstrated that intravenous ketorolac treatment had similar effects to intravenous metoclopramide treatment. In addition, the adverse events were not significantly different. The only potentially significant outcome of difference between the 2 treatments might be short-term headache relief events. However, due to the nondefinitive 95% CI values of the short-term headache relief results and the low number of included studies for these results, the research needs to be replicated in the future with more studies focusing on this outcome.

A previous systematic review of ketorolac for acute migraine attacks found that it might be as effective as meperidine and more effective than sumatriptan for the relief of acute migraine headaches. In addition, it was reported that ketorolac might not be as effective as metoclopramide.7 The present meta-analysis showed that ketorolac and metoclopramide might not produce significant differences in pain intensity, sustained headache relief or adverse events. Therefore, this study could serve as an update of ketorolac’s characteristics in comparison with metoclopramide.

Ketorolac has been a standard option for migraine treatment and has been compared to other new medications.16, 17, 18, 19 Therefore, the effects of ketorolac treatment should not be undervalued, especially for pain intensity, sustained headache relief and adverse events. The only effect for which intravenous ketorolac might be inferior to intravenous metoclopramide is short-term headache relief.

The American Headache Society and the Canadian Headache Society recommended that clinicians prescribe metoclopramide for patients with acute migraines.20, 21 However, intravenous metoclopramide was not superior to intravenous ketorolac in terms of pain intensity, sustained headache relief and adverse events. Our meta-analysis results support those of another meta-analysis on metoclopramide treatment for acute migraines, which suggests that metoclopramide is not associated with more significant adverse events than other kinds of medications.22

There is a lack of experimental evidence regarding the possible mechanism of the anti-migraine effects of metoclopramide, but underlying dopamine D2 antagonism and the related decrease in trigeminovascular activation might explain the treatment efficacy of metoclopramide for acute migraines.23 Dopamine D2 antagonism may be related to extrapyramidal side effects, such as Parkinsonism and acute dystonia.24, 25 Thus, clinicians may consider the use of ketorolac for patients with migraines if they have concerns about the side effects of metoclopramide, such as extrapyramidal side effects.

For short-term headache relief, intravenous metoclopramide showed superior effects when compared to intravenous ketorolac. This is consistent with the recommendations made by the American Headache Society and the Canadian Headache Society. In our results, the highest dosage of intravenous metoclopramide was 10 mg, which corresponds with a study on the appropriate dose of metoclopramide.26 Therefore, our research should be replicable in clinical practice when clinicians are treating acute migraines, considering different dimensions of outcomes, and determining their treatment goals.

Limitations

Several limitations of our meta-analysis need to be mentioned. First, the included RCTs were limited in sample size. Therefore, large RCTs on this topic are warranted. Furthermore, the variable doses and types of ketorolac and metoclopramide treatments might have biased our results. However, in recent years, clinical practice regarding migraine treatment has still included ketorolac and metoclopramide. Thus, the present results might provide useful information for clinical practice.

Another issue is that the low numbers of included RCTs addressing several outcomes, such as short-term headache relief, might be a concern with regard to the significance of the results. In addition, the 95% CI of the only significant result might be another issue of concern. The lack of patient-level data and covariates might have led to bias. Not all included RCTs reported all the outcomes in a consistent style, and some of them reported results in a format that could not be used in the collection of data for our meta-analysis. The different definitions and severities of migraine headaches addressed in the included RCTs might have also influenced our results, and there was a lack of demographic data on the ketorolac and metoclopramide groups. Additionally, the different representations of the sexes of participants in some included RCTs might be a concern.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis compared the effect of intravenous ketorolac with metoclopramide treatment on adult migraine patients. The results suggest that the differences in most treatment effects and adverse effects are not significant between the treatments, with the exception of short-term headache relief. However, few studies available on this topic might have been a limitation in the analysis. Thus, more studies are warranted to confirm the results.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8299830. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. The forest plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of sustained headache relief (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide, Mantel–Haenszel method).

Supplementary Fig. 2. The funnel plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of sustained headache relief (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 3. The forest plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of adverse events (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 4. The funnel plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of adverse events (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 5. The forest plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of drowsiness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 6. The funnel plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of drowsiness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 7. The forest plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of restlessness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 8. The funnel plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of restlessness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 9. The forest plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of high restlessness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).

Supplementary Fig. 10. The funnel plot of RR for the meta-analysis results of high restlessness (ketorolac compared to metoclopramide).