Abstract

Background. Circulating cancer cells have characteristics of tumor self-targeting. Modified circulating tumor cells may serve as tumor-targeted cellular drugs. Tremella fuciformis-derived polysaccharide (TFP) is related to immune regulation and tumor inhibition, so could B16 cells reeducated by TFP be an effective anti-tumor drug?

Objectives. To evaluate the intrinsic therapeutic potential of B16 cells exposed to TFP and clarify the therapeutic molecules or pathways altered by this process.

Materials and methods. RNA-seq technology was used to study the effect of TFP-reeducated B16 cells on the immune and inflammatory system by placing the allograft subcutaneously in C57BL/6 mice.

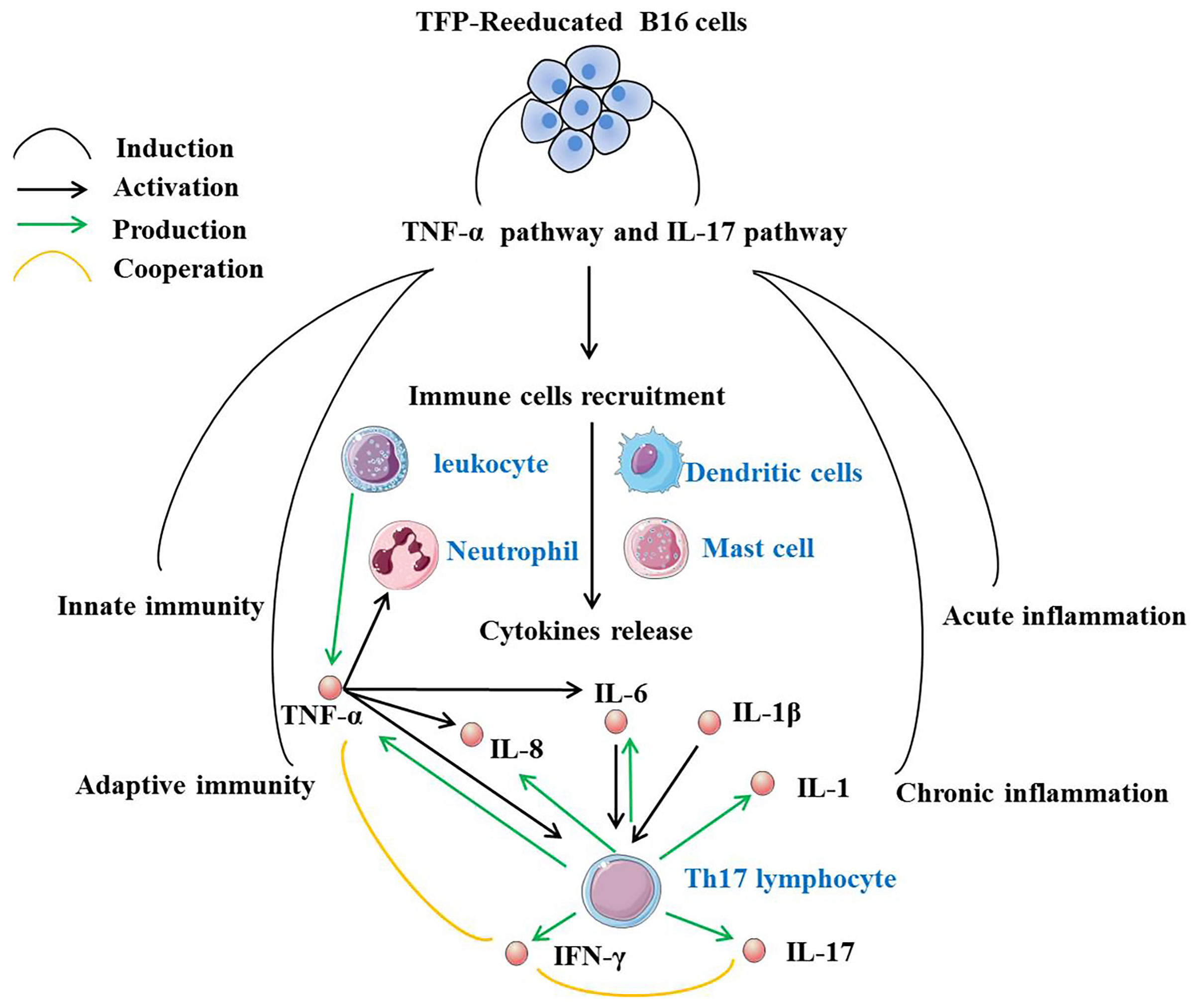

Results. Tremella fuciformis-derived polysaccharide-reeducated B16 cells recruited leukocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), and mast cells into the subcutaneous region and promoted the infiltration of several cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and interleukin 1 (IL-1). Tumor necrosis factor alpha also activated Th17 lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 17 (IL-17) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ). The co-expression of IFN-γ and IL-17 was favorable for tumor immunity to shrink tumors. In short, TFP-reeducated B16 cells activated the innate and adaptive immune responses, especially Th17 cell differentiation and IFN-γ production, as well as the TNF-α signaling pathway, which re-regulated the inflammatory and immune systems.

Conclusions. B16 cells subcutaneously exposed to TFP in mice induced an immune and inflammatory response to inhibit tumors. The study of the function of TFP-reeducated B16 cells to improve cancer immunotherapy may be of particular research interest. This approach could be an alternative and more efficient strategy to deliver cytokines and open up new possibilities for long-lasting, multi-level tumor control.

Key words: IL-17, TNF-α, Tremella fuciformis-derived polysaccharide, reeducated B16 melanoma, RNA-seq technology

Background

A tumor is the result of a complex interaction between malignant and normal cells, including immune cells. Immune evasion and tumor-promoting inflammation are hallmarks of cancer.1, 2

The immune system is divided into 2 primary branches: innate and adaptive immunity. These branches provide comprehensive cellular and molecular protection from a wide range of diseases, including infectious diseases and cancer.3 In the early stages of carcinogenesis, innate immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells) provide a robust 1st line of defense against cancer cell-associated “danger signals” through an acute inflammatory response to initiate cancer recognition, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and elimination of cancer cells by innate immune cells.4, 5 The innate immune response is of critical importance for the formation of an effective anti-tumor adaptive immune response.6 The adaptive immune response occurs subsequent to the innate immune response. Dendritic cells migrate, present tumor antigens, and activate tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These specific T cells migrate to the tumor site and facilitate killing of tumor cells to prevent the occurrence and development of a tumor.7 Cancer cells modulate the functions of immune cells surrounding the tumor.8 The formation and development of tumors are the result of complex interactions between cancer cells and immune cells. Each immune cell type has a dual effect of immune promotion and immune suppression, making immunity present a double-edged sword: they hinder cancer progression or promote tumor activity.3, 9

Immune cell populations co-evolve with cancer cells, sculpt the progression of the tumor and produce sustained inflammatory pathways.10 Inflammation has been proven to be closely related to all stages of most cancers. Inflammation processes are driven by immune cells and molecules released by immune cells, which mediate the interactions between these cells.11 The communication at the cellular and molecular levels ensures a balance between immune response activation and inhibition.8 More and more evidence suggests that the tumor microenvironment (TME) is one of the main obstacles to cancer immunotherapy, with chronic inflammation playing a major role in tumor cell proliferation and immune suppression,12 but acute inflammation caused by certain therapies can reeducate tumor-promoting TMEs to re-enter the anti-tumor immune microenvironment.13, 14, 15

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is mainly produced by macrophages, monocytes, T cells, NK cells, B cells, and fibroblasts.16 It is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays an important role in host defenses and acute and chronic inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates many pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8 and TNF-α itself, as well as adhesion molecules, chemokines and metalloproteinases.17 On the other hand, TNF-α promotes the synthesis of anti-inflammatory factors and limits the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. It is also an essential signaling protein in the innate and adaptive immune systems,18 which can promote the recruitment of immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes to inflammatory sites.19

T cells are activated during the inflammatory process and differentiate into Th17 cells under conditions of IL-1β, tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β) and IL-6.20 Th17 cells have been recognized to play a dual role in tumor development. According to Zhao et al., Th17 cells have the effects of promoting and suppressing tumors.21 High levels of Th17 cells are associated with an improved prognosis.22 Th17 cells have been shown to recruit immune cells into tumors, activate effector CD8+ T cells, directly convert them into Th1 phenotype, and produce interferon gamma (IFN-γ) to kill tumor cells.21 Melanoma patients who exhibit an increase in the number of Th17 cells have been reported to have a higher survival rate.23 Some studies have shown that if Th17 cells are the only immune cells, they can promote cancer, but have protective function in the presence of other immune cells.24 The presence of other immune cells promotes the protective role of Th17 cells dependent on IFN-γ, and its co-expression with IL-17 is beneficial to shrink the tumor.25 Interferon gamma exerts its anti-cancer effect by tumor angiogenesis inhibition, cytokine secretion, anti-proliferative activity, and stimulating anti-tumor immunity in the TME.26

Tumor necrosis factor alpha is also one of the major effector cytokines secreted by pathogenic Th17 cells, initiating the production and release of IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17.27 Interleukin 17 is known to stimulate TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β production, while IL-1β acts synergistically with IL-6 to induce pro-inflammatory Th 17 cell differentiation.28 Studies have shown that the presence of TNF-α and IL-1β is required for the maximum effects of IL-17.29 Interleukin 17 can cooperate with TNF-α to induce a synergistic response.30 Tumor necrosis factor alpha and IFN-γ accelerate NF-κB-mediated cell apoptosis.26

The effect of TNF-α on inducing cancer cell death or survival depends on the cellular microenvironment.26 Many efforts have been made to enhance the anti-tumor effect and reduce the systemic toxicity of TNF-α, including cell-based therapy. A recent study showed that systemically administered TNF-expressing tumor cells can localize tumors, release TNF-α locally and induce cancer cell apoptosis, reducing the growth of both primary tumors and metastatic colonies in immunocompetent mice.31

Cancer cells can educate innate immune cells to exert tumor protection and immunosuppressive activities.32 Tremella fuciformis-derived polysaccharide-reeducated B16 cells (TFP-B16 cells) may locally activate the TNF-α signaling pathway, Th17 cell differentiation and pro-inflammatory cytokines release, promote cytokine-cytokine interactions, induce immune-inflammatory profile changes, and may possess therapeutic potential by engineering them to attack melanoma cells.

Objectives

This study used RNA-seq technology to investigate the effects of TFP-B16 cells on the immune and inflammatory systems of C57 BL/6 mice after subcutaneous transplantation. Additionally, the study evaluated the therapeutic potential of B16 cell exposure to TFP and the therapeutic molecules or pathways activated by these cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and mice treatment

B16 cells were provided by Stem Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China), and were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks, 18–20 g) were purchased from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center (Shanghai, China). They were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment (25˚C, 30–40%), kept on a 12-h light/dark cycle, and provided with an unrestricted amount of rodent chow (corn 40–43%, bran 26%, soybean cake 29%, salt 1%, bone meal 1%, lysine 1%, vitamins 1%) and water. After 1 week of acclimatization, the mice were randomly divided into 2 groups: the model group and the TFP group. After exposure to 5 mg/mL of TFP for 24 h, B16 cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 1×106 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of the mice. For the vehicle control, the same amount of B16 cells were subcutaneously inoculated as described.

RNA extraction, library construction and RNA-seq analysis

Six tumor tissues from the model and TFP groups were used for RNA-seq analysis. Total RNA was extracted using a Trizol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA enriched using Oligo (dT) beads was fragmented into short fragments and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. The purified double-stranded cDNA fragments were end-repaired, poly (A) added, ligated to adaptors, and screened for approx. 200 bp cDNA using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) After polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, the cDNA library was built and sequenced using Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co.; Guangzhou, China).

Sequencing data processing and interpretation

Raw reads containing adapters reads containing more than 10% known nucleotides (N) and low-quality reads containing more than 50% low-quality (Q-value ≤10) bases were filtered using fastp33 from the raw data. The rRNA reads were removed from the clean data to obtain effective data using Bowtie2.34 The remaining clean reads were further used in assembly and gene abundance calculations. The final clean data were mapped to the Mus musculus genome (Ensembl release104) using HISAT2.35 The sequenced data reported in this study was archived in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the BioProject ID PRJNA772896.

Identification of differentially expressed genes and enrichment analysis

The mapped reads of each sample were assembled using StringTie (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/index.shtml)36, 37 in a reference-based approach. Gene abundances and variations were analyzed using RSEM software (http://deweylab.github.io/RSEM/)38 and normalized by fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. The RNA differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html)39 software for the 2 groups. The genes identified using the parameters of a false discovery rate (FDR) below 0.05 and absolute fold change ≥2 were considered significant DEGs.

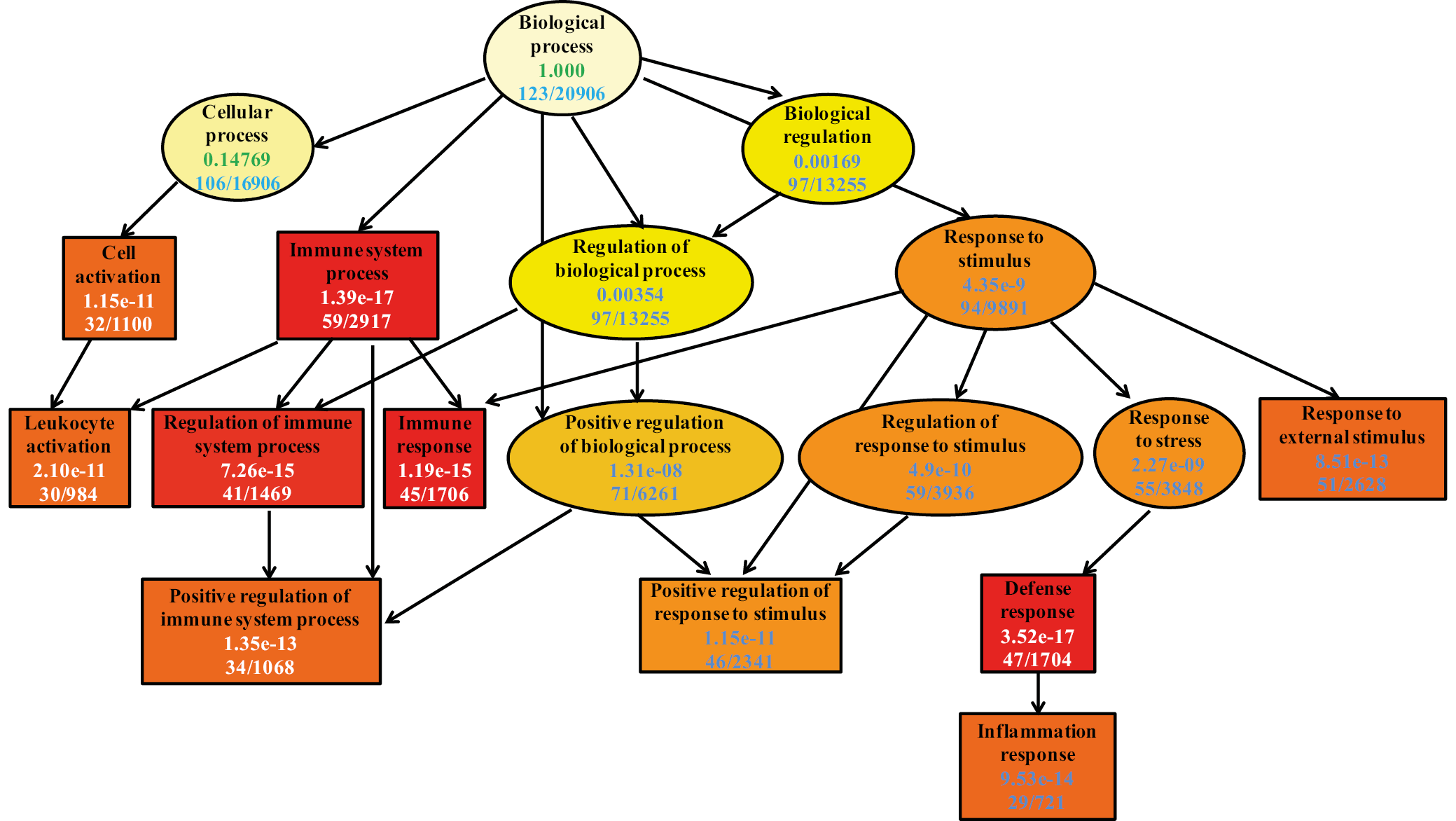

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed. All DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the GO database (http://www.geneontology.org), gene numbers were calculated for every term, and significantly enriched GO terms in DEGs compared to the background genome were defined using the hypergeometric test. The calculated p-value went through FDR correction, using FDR ≤ 0.05 as the threshold. The biological pathways of the DEGs were enriched to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp) using the same hypergeometric test as used for GO term enrichment. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was used to identify whether a set of genes in specific GO terms\KEGG pathways showed significant differences between the 2 groups (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp).

Results

The TFP-B16 cells stimulated immune cell activation

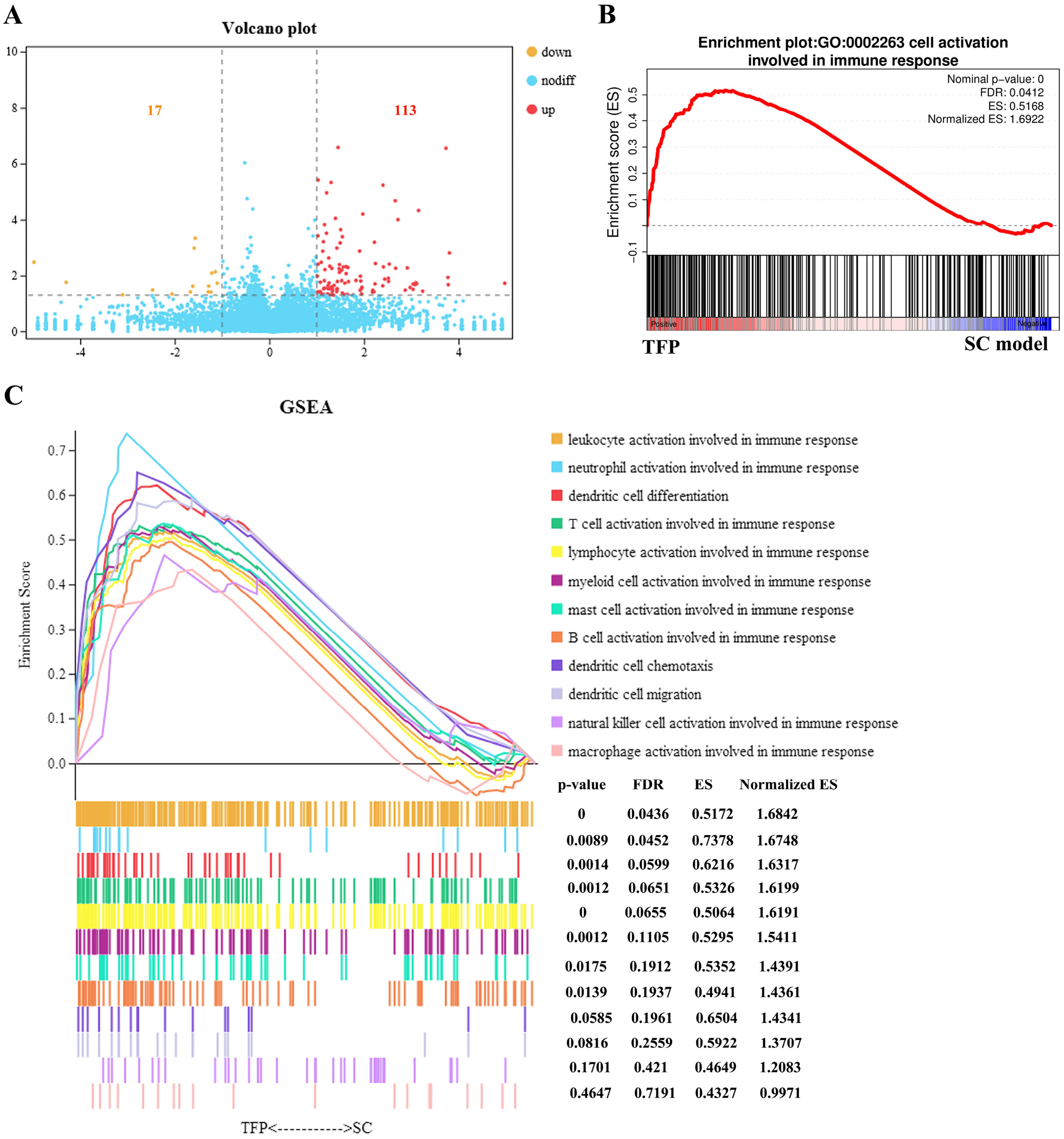

To detect the overall gene expression changes of allografts, we conducted RNA-seq analysis on the model and TFP groups. Figure 1A shows that TFP extensively regulates gene expression, with more upregulated genes (113) than downregulated genes (17), indicating that TFP mainly plays a role by promoting gene transcription.

To characterize immune states, GSEA analysis was used to identify the immune system response in the TFP group. The data showed that the TFP-B16-treated group was positive for “cell activation involved in immune response,” as shown in Figure 1B. Leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes (T cells and B cells), and mast cells were activated in the immune response, but NK cell and macrophage activation were not significantly increased, as shown in Figure 1C. Dendritic cells underwent significant differentiation. These data show that TFP-B16 cells promote more immune cell infiltration into the allograft compared to the model group.

TFP-B16 cells activated innate and adaptive immune response

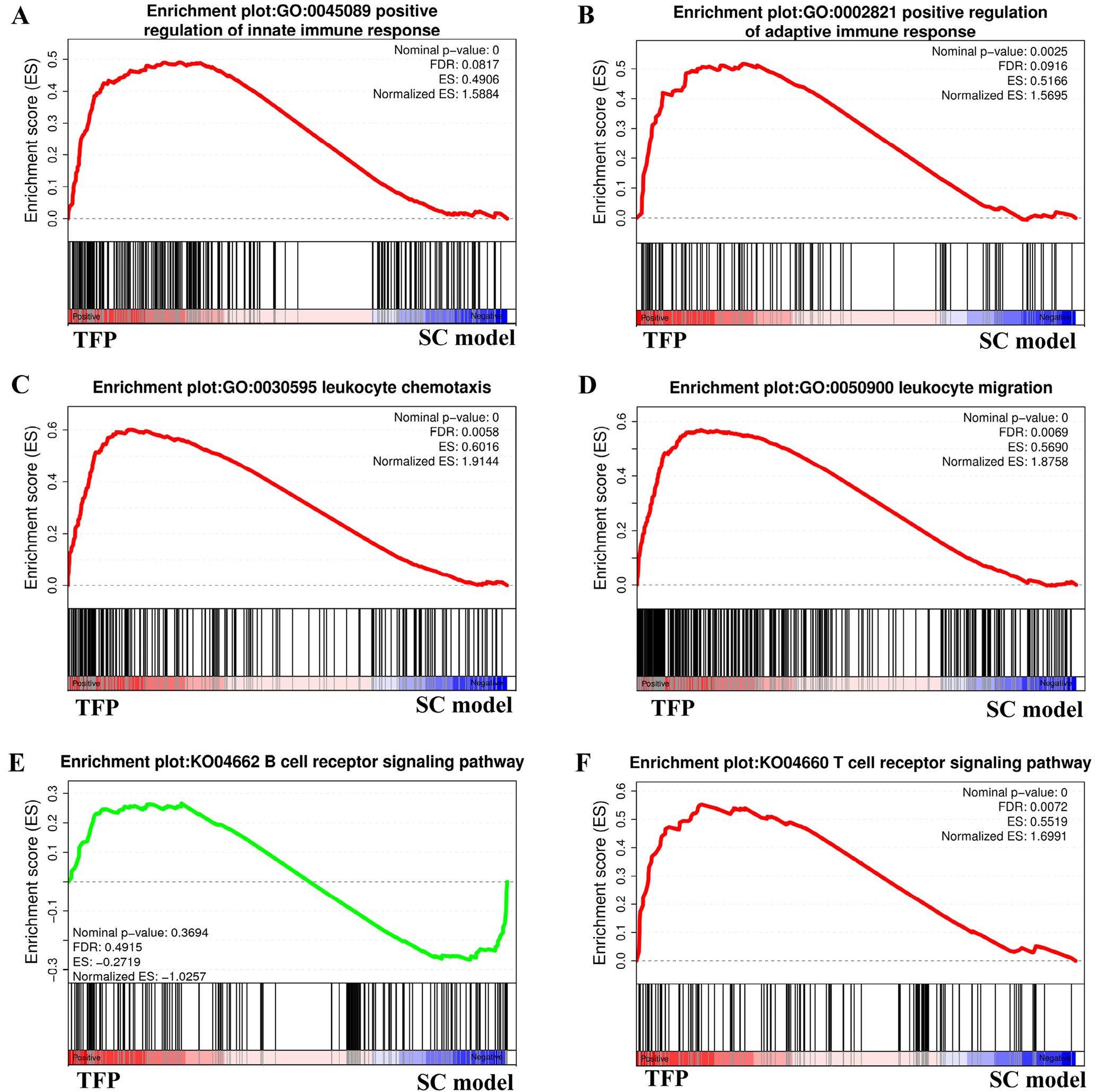

The GSEA showed that there were significant differences in the “positive regulation of innate immune response” (Figure 2A) and “positive regulation of adaptive immune response” (Figure 2B) gene sets between the TFP-B16 and SC groups, and most of the genes in the 2 pathway gene sets were upregulated in the TFP-B16 group.

In the early stage of immunity, leukocyte synthesis, migration and release of TNF-α and IL-1 cytokines have been found to promote pro-inflammatory effects.21 The TFP-B16 cells in the treatment group showed positive results in “leukocyte chemotaxis” and “leukocyte migration,” as shown in Figure 2C and Figure 2D. These data indicate that TFP-B16 cells activated innate immunity which has an important role in the early phases of anti-tumorigenesis.

Dendritic cells can process foreign antigens and present them to T lymphocytes, initiating a specific adaptive immune response.40 Activated adaptive immune cells, including T and B lymphocytes, are known to further amplify the initial inflammatory response. The “T cell receptor signaling pathway” was activated but not the “B cell receptor signaling pathway,” as shown in Figure 2E and Figure 2F. This data indicated that the infiltrating adaptive immune system cells are primarily T lymphocytes, and the T cell receptor signaling pathways were activated.

TFP-B16 cells induce inflammation via TNF-α and IL-17 pathway activation

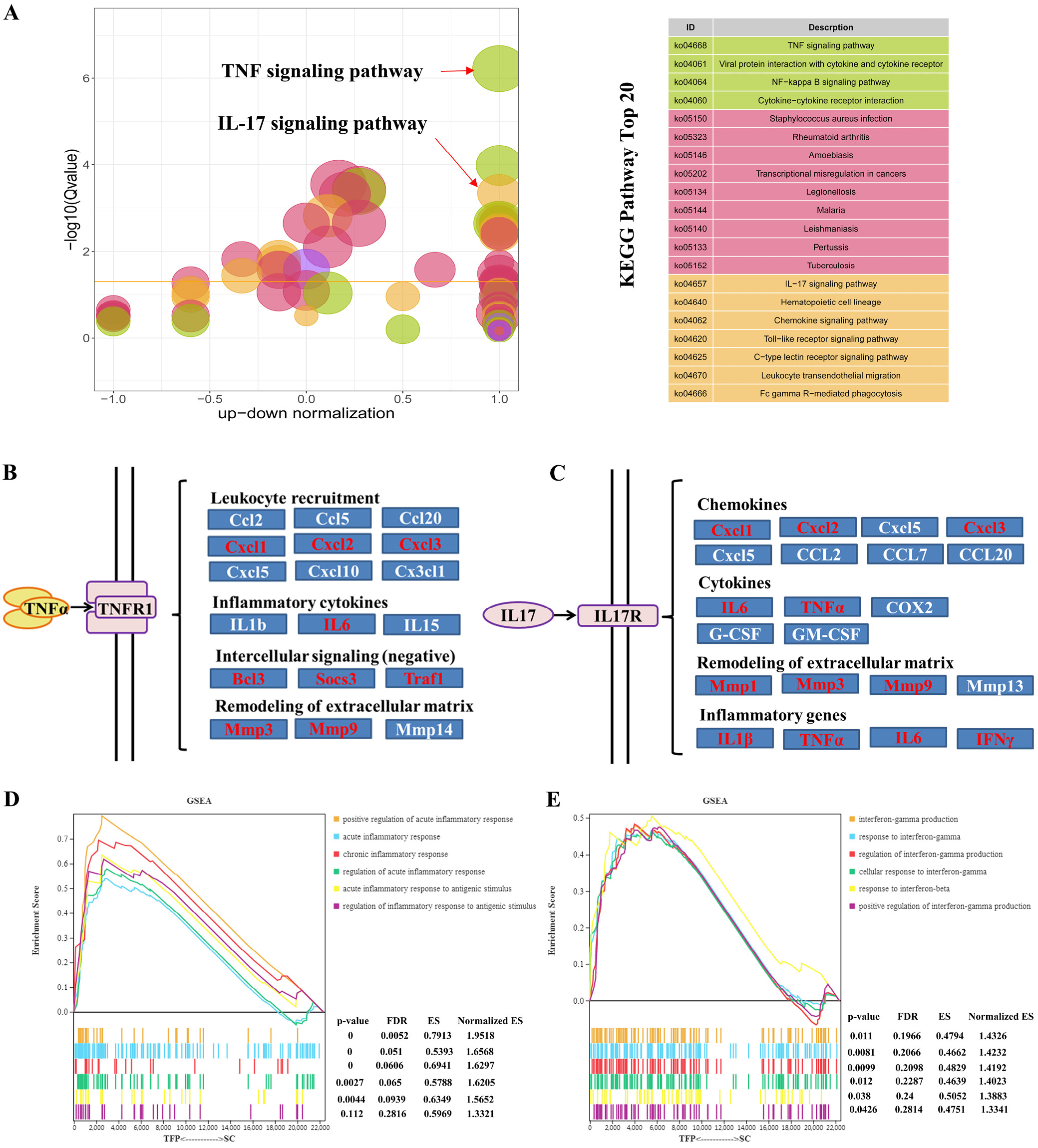

To further uncover the effects of TFP-B16 cells on the immune-inflammatory environment, the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that TNF-α and IL-17 signaling pathways were significantly altered by the TFP-B16 cell group. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 3A, TFP significantly altered NF-κB signaling pathways and cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-κB needs to convert immature DCs into functionally mature effector cells and then stimulate naïve T-cells to initiate antigen-specific T-cell responses.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling pathways via TNFR1 mainly trigger pro-inflammatory and apoptotic effects.41 The TFP-B16 cells promoted leukocyte recruitment and inflammatory cytokine secretion, negatively regulated intercellular signaling, and remodeled the extracellular matrix, as shown in Figure 3B. The TFP-B16 cells also promoted chemokines, cytokines and inflammatory genes and remodeling of the extracellular matrix via IL-17 through the IL-17 receptor, as shown in Figure 3C.

The GSEA showed that more pathways related to acute inflammation were significantly increased in the TFP-B16 cells as shown in Figure 3D. Acute inflammation is the initial response to harmful stimuli,42 while chronic inflammation promotes the development, progression and metastasis of tumors. This data suggested that TFP-B16 cells activated the acute inflammatory response, which had an important role in the early phase of anti-tumorigenesis.

The GSEA of IFN-γ showed that IFN-γ production and response to IFN-γ was significantly upregulated by TFP-B16 cells, as shown in Figure 3E, which suggested that IFN-γ plays an important role in immune regulation. The use of TFP-B16 cells is a novel strategy to modulate TNF-α and IFN-γ pathways; such an approach would have the benefit of triggering protective immunity.

The interplay of TFP-B16 cells on the immune-inflammatory system

The most significant impacts by TFP-B16 cells were seen on the “immune system process (p = 1.39e-17),” “regulation of the immune system process (p = 7.26e-15),” “immune response (p = 1.19e-15),” and “defense response (p = 3.52e-17)”. The impact on “cell activation (p = 1.19e-11),” “leukocyte activation (p = 2.10e-11),” “positive regulation of immune system process (p = 1.35e-13),” “response to external stimulus (p = 8.51e-13),” and “inflammation response (p = 9.53e-14)” was followed by the impact on “positive regulation of response to stimulus (p = 1.15e-11),” and these GO terms were all in the top 10. This data confirmed that TFP-B16 cells regulate immune and inflammation responses and can influence the immune response, as shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

The complex immunosuppressive networks formed by inflammatory cells, tumor cells and their secreted cytokines in the TME play a pivotal role in tumor immune escape.43 The cytokine content can tip the balance between immunosuppressive and immune-activating factors within tumors.44 The specific blockade of inhibition pathways in the TME is expected to effectively prevent immune escape and tumor tolerance.

The ineffectiveness of traditional cytokine therapy is primarily attributed to the presence of numerous immunosuppressive cytokines and chemokines in the TME.43 Several studies have directed cytokines specifically to tumors using engineered cytokine-producing T-cells or targeted nanoparticle systems.45 Advances in polysaccharide-based nanosystems have the potential to enhance the local delivery of immunotherapeutic agents, reprogram immune regulatory cells, promote inflammatory cytokines, and block immune checkpoints in addition to receptor-mediated active targeting.46

Attracting tumor-specific immune cells or immunomodulatory factors directly to tumor sites47 rather than stimulating the entire leukocyte population non-specifically has the potential to address systemic toxicity and adverse side effects.43 Tumor cells manipulated in vitro circulate through the blood, creating the potential for efficient direct targeting of immune cell proliferation and providing a source for self-amplification of appropriate immunity, and can serve as a unique and effective carrier for delivering bioactive cytokines to the parental tumor through their homing characteristics, especially in highly metastatic cells.31

There are few reports on the use of polysaccharide-modified tumor cells for the treatment of tumors. In this study, inflammatory and immune responses in the subcutaneous region induced by the TFP-B16 cells were explored using transcriptome analysis.

The immune and inflammation process induced by subcutaneous injection of TFP-B16 cells begins with a local cellular response to an extracellular stimulus and the activation of innate (leukocytes, neutrophils, myeloid cells, mast cells, DCs) and adaptive immune cells (T and B cells). Cytokines and chemokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, and TNF-α are produced to amplify the local inflammatory process after immune cell migration and adaptive immune response initiation. Tumor necrosis factor alpha has been identified as one of the most effective molecules for mediating important anti-tumor immune effects that disrupt tumors.48 Systemic administration of TNF-α can lead to significant off-target toxicities, thereby limiting the administrable concentration and resulting in lower efficacy.49 The methods to stimulate endogenous TNF-α release are currently being evaluated as a long-term regulatory immune intervention.50 The TFP-B16 cells elevated TNF-α, which constitutes a TME signal that biases recruited immune cells toward anti-tumor and pro-inflammatory activities. Tumor necrosis factor alpha has cytotoxic effects and induces the secretion of other cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6. This reaction results in cytokine- and chemokines-mediated damage to target tissues.

Moreover, TFP-B16 cells and their tumor environment not only provide soluble cytokines but also provide unknown cell–cell contact signaling for the expansion of Th17 cells. The TFP-B16 cells upregulated IL-17 production by Th17 cells. Interleukin 17 stimulates CXCL2 and CXCL3 production, attracts IFN-γ anti-tumor neutrophils in vivo, and inhibits tumor growth.51 Several studies have shown that tumor-specific Th17 polarized cells reduce the advancement of B16 melanoma in a mouse model, and this process heavily depends on IFN-γ production.52

The results revealed heterogeneity in the content of the factors produced by B16 cells and in their impact on the expression of inflammatory and immunity traits. Through these interactions, TFP-B16 cells reshaped the immune and inflammatory microenvironment and may thus inhibit tumor progression.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the present study. First, due to the crucial importance of tumor cells expressing TNF-α for anti-tumor activity, further detection of TNF-α expression in tumor or blood circulation is necessary. Second, the anti-tumor effect and mechanism of B16 cells reprogrammed by TFP are needed in the future mouse models of tumor cells.

Conclusions

Administration of TFP-B16 cells could lead to activation of anti-tumor mechanisms locally and reduced counter-regulatory mechanisms through modification by TFP. This approach would be an alternative and more efficient strategy to deliver cytokines and open up new possibilities for long-term and multi-level tumor control.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10992031. The package includes the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. Statistical table of data filtering.

Supplementary Table 2. Statistical table of base information.

Supplementary Table 3. Statistical table of ribosomal comparison.

Supplementary Table 4. Statistical table of reference comparison.

Supplementary Table 5. The original data of Figure 3A.

Supplementary Table 6. The original data of Figure 4.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.