Abstract

Background. Prostate cancer (PC) prevention is effectively achieved through its inhibition. Oridonin (ORD), an active diterpenoid isolated from Rabdosia rubescens, has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on PC cells, although its impact on PC is unknown.

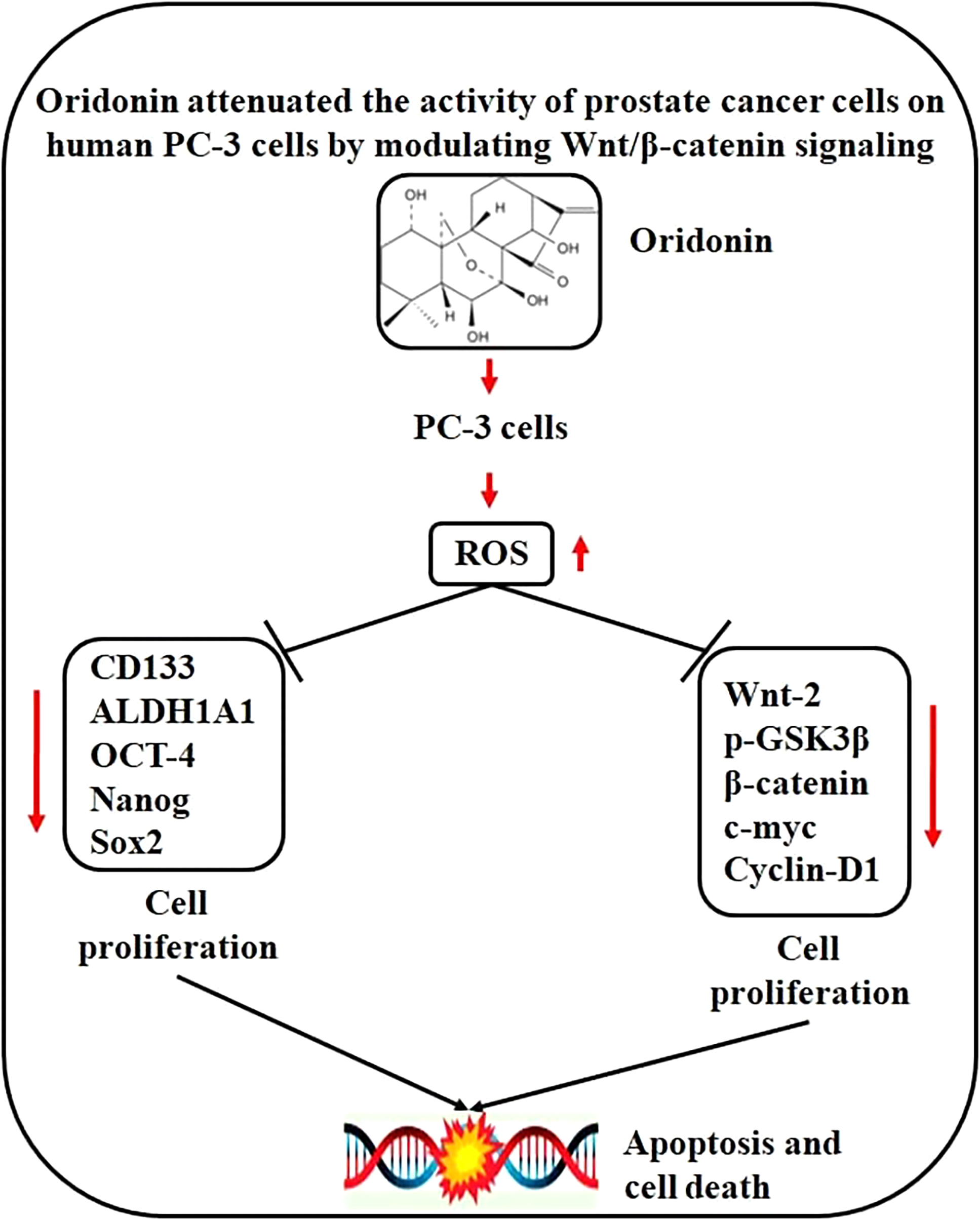

Objectives. The present work investigated the actions and probable mechanisms of ORD on cellular proliferation, apoptosis, PC, and the wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling pathway using the androgen-independent PC-3 cell line.

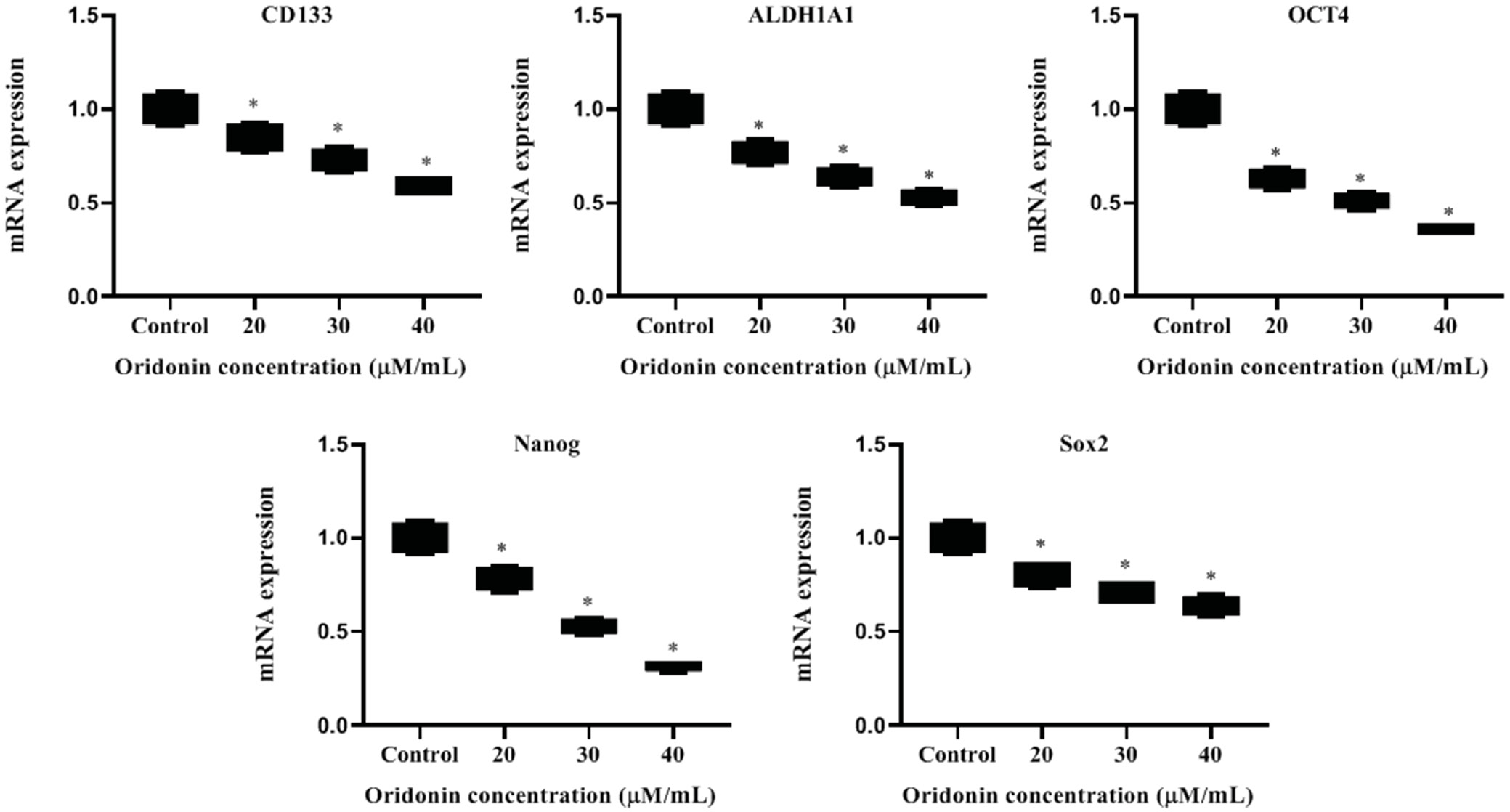

Materials and methods. In this study, cell viability was analyzed with MTT assay method, apoptotic morphology determined using DAPI dye method, while protein (CD1333, OCT-4, Nanog, SOX-2 & Aldh1A1) and mRNA expressions were analyzed with western blotting and real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

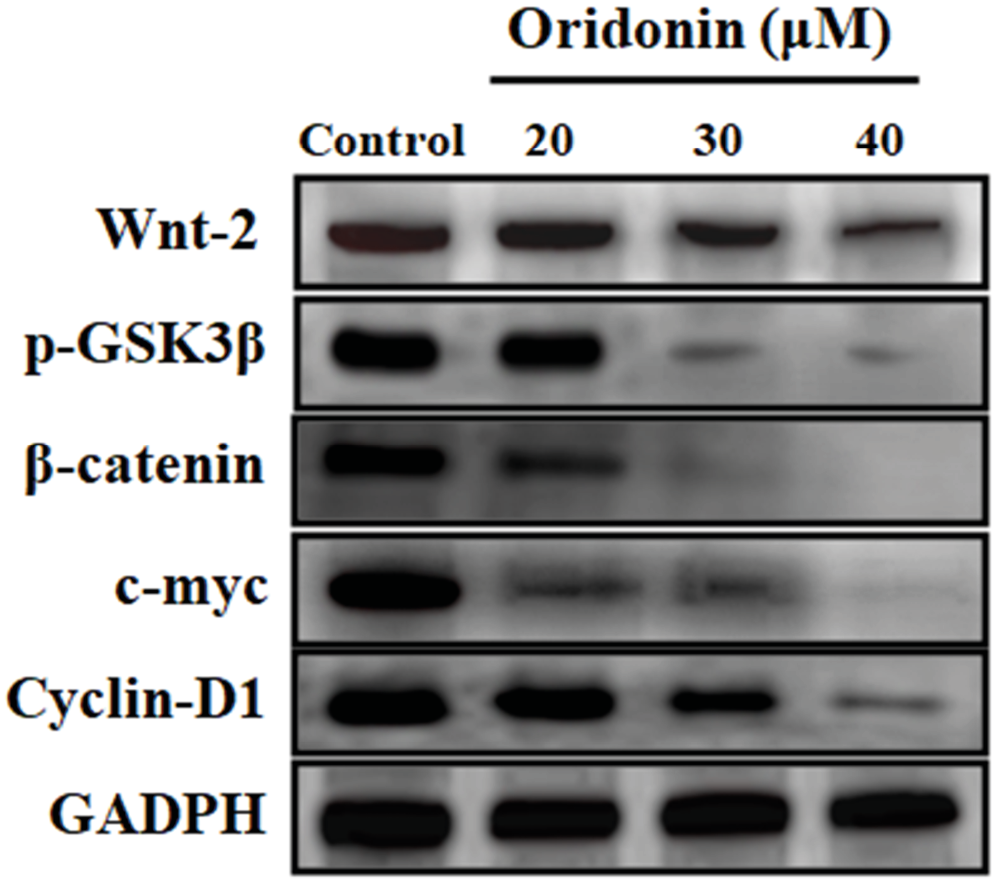

Results. We demonstrated a concentration-dependent ORD inhibition of PC-3 cell proliferation and inhibition of induction apoptosis. Furthermore, ORD decreased PC-3 Wnt-2, phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase-3 (p-GSK3), and β-catenin protein levels and downregulated cyclin-D1 and c-myc messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA).

Conclusions. Oridonin inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in PC-3 cells, with the findings suggesting that it acted via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to exert its effects. This study demonstrates that ORD may impact PC.

Key words: apoptosis, oridonin, prostate cancer, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, PC-3 cells

Background

The world’s most prevalent malignancy, prostate cancer (PC), accounts for 30% of all malignant tumors in men.1 Prostate cancer contributes to 10% of all mortality and ranks as the 2nd major risk of cancer-associated deaths in western countries,2 with the USA reporting 191,930 new cases and 33,330 deaths in 2020.3 Prostate cancer mortality results from bone and lymph node metastasis and mortality rate of cancer progression through androgen-dependent to androgen-independent prostatic growth reversion.4 The PC androgen-dependent phase can be effectively treated with androgen withdrawal therapy, resulting in prostate gland involution due to cellular proliferation subdual and apoptosis activation.5 Although hormonal excision typically works as a first-line treatment against localized tumors, degeneration occurs in most patients after some years, and once the PC becomes androgen-independent, a highly metastatic tumor resistant to irradiation and chemotherapy develops.1, 6 Unfortunately, most patients eventually progress to the androgen-independent stage, for which there is no efficient life-extending management strategy.7, 8

Androgen-independent cancer progression, and its molecular mechanisms, are poorly understood. Therefore, research is required to better understand androgen-independent pathophysiology and identify beneficial treatment strategies for PC. Hence, a drug capable of controlling the signaling pathways involved in tumor progression without impacting hormone receptor expression could significantly improve metastatic PC therapy.

Oridonin (ORD) is an ent-kaurane diterpenoid sequestered from the aromatic plant Rabdosia rubescens, extensively used in traditional Chinese medicine.9 In vitro trials revealed that ORD stimulates apoptosis in various tumor cells such as acute leukemia, gliomas, non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer, with these studies showing that ORD promotes cell death, enhances phagocytosis, and prevents cell cycle progression.10, 11 Previous research has also demonstrated ORD apoptotic and anti-proliferative properties in several malignant cells, such as colorectal, mammary and liver cancer.12, 13, 14 Furthermore, several in vitro and in vivo studies have reported ORD growth inhibition of many human malignancies, including oral cancer,15, 16 gallbladder carcinoma,17 glioblastoma,18 pancreatic tumors,19 cervical cancer,20 and esophageal cancer.21 In addition, recent research showed ORD supplementation to restrict growth and trigger apoptosis in PC cells (PCCs).22, 23, 24 However, the precise role of ORD anti-tumor activity remains unknown.

Several human cancer-derived cell lines with tumor cell characteristics have been recognized for genetic, chemoresistance and therapeutic drug studies.25 The latest method in cancer treatment is cancer cell (CC) targeting since breast cancer cells MCF7 participate in growth, metastasis, drug resistance, and cancer recurrence.26 The PCC markers, such as CD133, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (ALDH1A1), Nanog, octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct-4), and SRY-box transcription factor 2 (Sox2), are well-established and used to recognize the cells and assess their actions.27 Thus, CC targeting is likely the optimal tumor prevention and management strategy.

Recently, researchers have identified the wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling pathway as vital in controlling PCC activities.28, 29 Triggering of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is governed at the β-catenin level and regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3β), which mediates β-catenin phosphorylation to trigger β-catenin deprivation. Inactivation of β-catenin through GSK3β phosphorylation leads to its degradation, accumulation in the cytosol, and nuclear translocation to promote downstream gene targets such as cyclin-D1 and c-myc to act as transcription factors that control CC activity.30

Among PCCs, the androgen-independent PC-3 cell line has higher metastatic potential than others.31 Hence, the current study aimed to investigate ORD anti-proliferative action on PC-3 cells and explore its potential to induce apoptotic signaling pathways.

Objectives

The current research aimed to demonstrate, for the first time, ORD-driven suppression of CC markers and PC. Furthermore, we aimed to establish ORD attenuation of PCCs through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Oridonin, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics (CD133, ALDH1A1, OCT-4, Nanog, Sox2, Wnt-2, β-catenin, GSK3β, c-myc, cyclin-D1, and GAPDH), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham USA). The antibodies for western blot analysis were acquired from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture

The human PC-3 cell line was procured from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). The cells were grown and preserved in DMEM containing FBS (10%), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 U/mL) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and less than 95% humidified air.

Cell cytotoxicity assay

An MTT assay determined the influence of ORD on PC-3 cellular proliferation.32 PC-3 cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/well, incubated overnight in DMEM media, and then treated with different ORD dosages (10–60 μM) for 1 day at 37°C. An aliquot of MTT (10 µL) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 4 h to allow the conversion of MTT into insoluble formazan crystals through mitochondrial dehydrogenase. The subsequent formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 150 μL DMSO to the culture medium. Each experiment was repeated thrice, with cells grown in a culture medium containing DMSO used as a control. Optical density (OD) was determined at 490 nm using a microplate reader (PerkinElmer EnVision; PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA)) to assess proliferation, which was calculated as a percentage of untreated PC-3 cell proliferation (100%). Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) (drug concentration that caused a 50% reduction in the MTT assay) was also calculated.

Apoptosis exploration using

DAPI staining

Human PC-3 cells treated with ORD (20 µM/mL, 30 µM/mL or 40 µM/mL) in 96-well plates were fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) at 37°C for 10 min, and then stained using DAPI for 10 min to analyze the cellular changes associated with apoptosis.33 Finally, all slides were fixed on a glass slide and observed using fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS100; Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot study

Human PC-3 cells were treated with ORD (20 µM/mL, 30 µM/mL or 40 µM/mL) and incubated for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared using an ice-cold lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and then used for western blot analysis. Protein content measurement utilized a Protein BCA Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, USA). The western blot experiment involved electrophoretically dispersing the proteins and relocating them to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) film that was blocked overnight at 4°C using a probe before being treated with diluted (1:1000) primary antibodies, including anti-CD133, anti-Oct-4, anti-ALDHA1, anti-Sox2, anti-Nanog, anti-Wnt-2, anti-β-catenin, anti-phosphorylated(p)-GSK3β(ser9), anti-c-myc, anti-cyclin-D1 and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Appropriate secondary antibodies (1:5000) were then added to the films, with GAPDH used as an internal control. Proteins were visualized using a LI-COR Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, USA).

Determination of messenger ribonucleic acid levels using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from human cells PC-3 using TRIzol® reagent (Abcam, Cambridge, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was converted to complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) through reverse transcription using a high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Beyotime Biotechnology), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, the Fast Start SYBR Green Master Mix (Abcam) was employed to explore the cDNAs, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The band intensity was scrutinized using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Finally, the band intensity was measured using ImageJ 1.48 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA). A comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method was used to calculate the fold changes in the expression of each gene using the formula 2−ΔΔCt. The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were independently conducted in triplicate (n = 3) and repeated 3 times, with data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD). Statistical analysis employed GraphPad Prism v. 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) and IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) software. The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed the normality of data distribution and demonstrated a non-normal distribution, perhaps due to the small sample size. As such, the subsequent analysis used the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc comparison of intergroup variables (control: n = 6; 20 µM/mL: n = 6; 30 µM/mL: n = 6; and 40 µM/mL: n = 6). Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Table 2 and Table 3 show the results of comparing variables among groups.

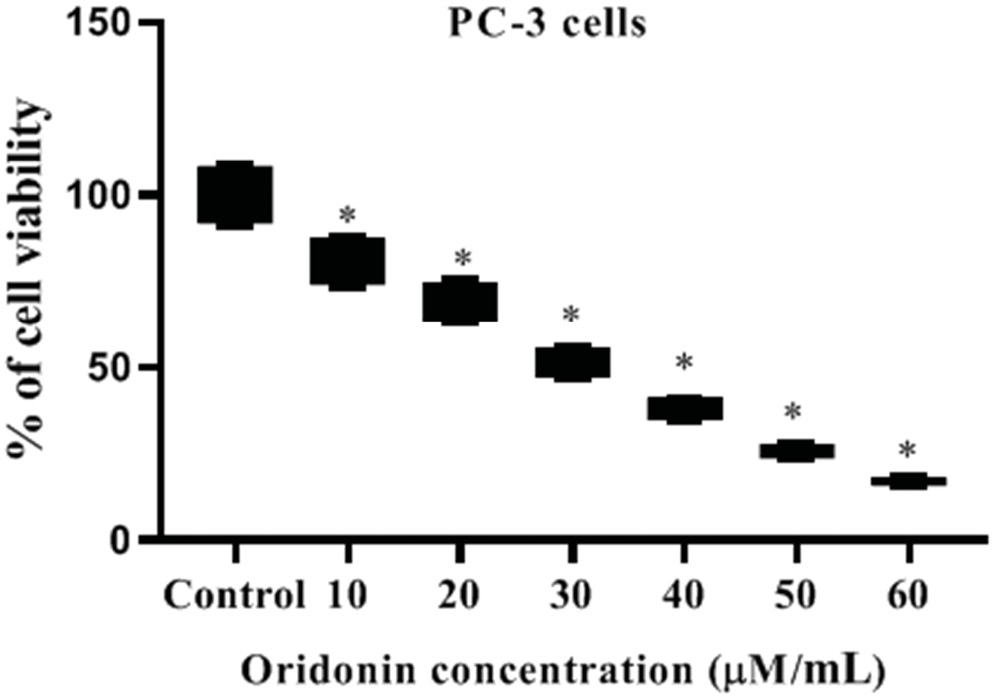

Cytotoxic effects of ORD

on human PC-3 cells

The cytotoxicity of a range of ORD concentrations (10 μM/mL, 20 μM/mL, 30 μM/mL, 40 μM/mL, 50 μM/mL, and 6 0μM/mL) on human PC-3 cells was determined using the MTT assay. The results revealed that ORD had a concentration-dependent anti-proliferative action on PC-3 cells. Untreated control cells did not experience any anti-proliferative effect and showed 100% PC-3 cell proliferation. However, 10 μM, 20 μM, 30 μM, and 40 μM ORD dosages substantially (p < 0.05) inhibited PC-3 viability compared to the untreated control. Furthermore, viability was inhibited further by administering a high dosage of ORD (50 μM and 60 μM), leading to cellular damage.

Results of the MTT assay showed that the ORD IC50 was 30 μM. Therefore, to avoid the damaging effects of high ORD concentrations (20 μM/mL, 30 μM/mL and 40 μM/mL), ORD was used for subsequent experiments (Figure 1).

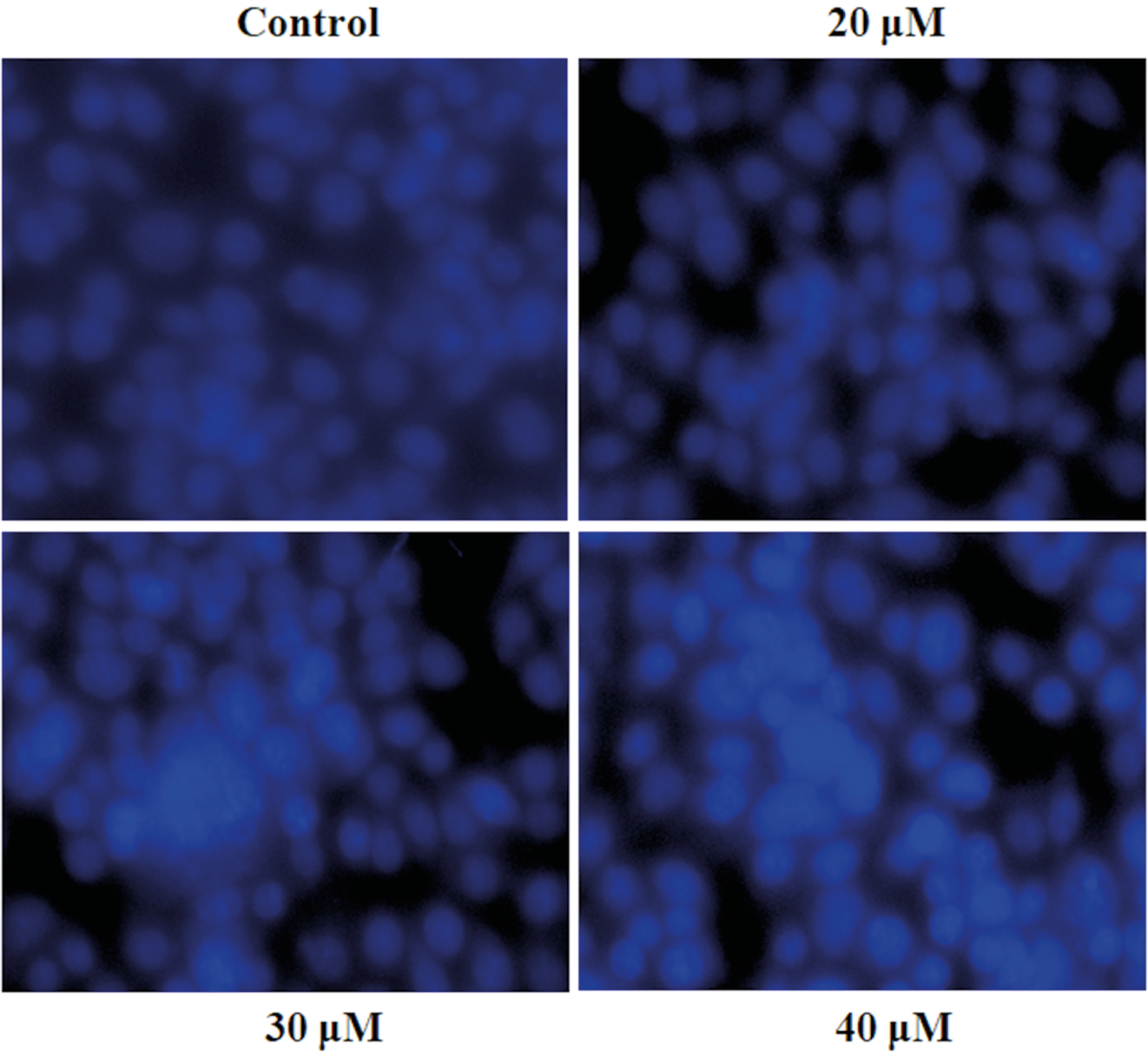

Oridonin triggered apoptosis

in DAPI-stained PC-3 cells

Assessment of ORD (20 µM/mL, 30 µM/mL and 40 µM/mL) on PC-3 cell morphological apoptotic features utilized DAPI staining. Control cells stained with DAPI were viable with normal nuclei. In contrast, ORD-treated PC-3 cells appeared apoptotic, based on nuclear morphology and body disintegration. Furthermore, PC-3 cells exposed to ORD (20 µM/mL, 30 µM/mL or 40 μM/mL) displayed chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing, nuclear envelop impairment, fragmentation, and cellular collapse in a concentration-dependent manner. These results demonstrated that ORD exhibits anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity on PC-3 cells in a dose-dependent way (Figure 2).

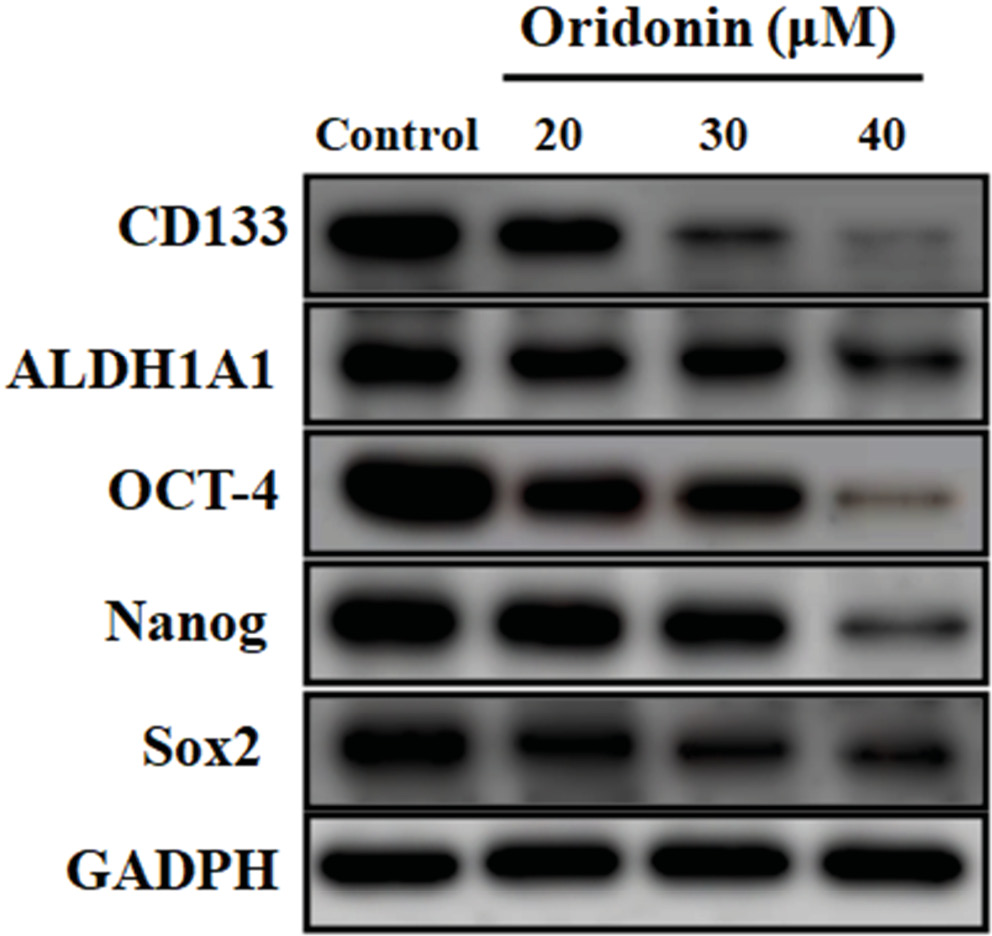

Oridonin suppressed PCC protein

and messenger RNA expression

We evaluated the effect of ORD on the protein and mRNA levels of PCC markers. Western blot and qPCR assays indicated that ORD attenuated the levels of protein and messenger (m)RNA of CD133, Oct-4, Sox2, ALDH1A1, and Nanog in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3, Figure 4). These findings demonstrated that ORD could suppress PCC activity.

Oridonin inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling in PC-3 cells

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a crucial pathway for controlling PC-3 cell actions. Accordingly, we investigated whether the anti-proliferative activities of ORD on PC-3 cells were facilitated by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The findings indicated that ORD repressed Wnt-2, β-catenin and p-GSK3β protein levels, and attenuated cyclin-D1 and c-myc genes (Figure 5).

Discussion

Prostate cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in males and the 2nd leading source of tumor-associated deaths in American men.1, 3 Metastatic PC is the end-phase and leads to most tumor-related deaths. Moreover, metastatic PC sufferers are at a higher risk of emerging bone metastasis, which ultimately results in skeletal illness.4 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved chemotherapeutic drugs docetaxel and cabazitaxel are used for metastatic PC treatment. However, these medicines have serious and potentially lethal side effects.34, 35 Regardless of recent research on putative therapeutics, our knowledge of PC is still limited, including its source and signaling pathways.5, 6 Nonetheless, PCCs are regarded as a cause of sustained prostate carcinogenesis.26 Thus, finding PCC-targeted medications might lead to their removal and produce beneficial effects.27

Oridonin’s anti-tumor capabilities include reducing viability and promoting apoptosis in various malignant cells.10, 11 Moreover, numerous research has reported that ORD suppressed cell growth and induction of cell-cycle arrest in a range of CCs.12, 14 Several mechanisms have been postulated to take part in the anti-cancer ability of ORD, such as proliferation inhibition, apoptosis triggering, cell cycle arrest, caspase activation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and subdual of protein kinase B (Akt) signaling and other pathways.15, 21 Indeed, ORD decreases cell proliferation through death receptor 5 over-stimulation and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation attenuation in ovarian and breast cancer cells.12 However, the effects of ORD in human PC are still uncertain, with limited information on the signaling pathways and mechanisms responsible for its pathophysiology.

In the current study, we established the anti-proliferative activity of ORD on human androgen-independent PC-3 cells, with the results showing that ORD blocked PCC proliferation and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and induced apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner. These outcomes are in agreement with the previous findings on ORD in leukemia cells and others.10, 11 Apoptosis is a well-categorized cell death program that can be triggered by various anti-tumor mediators through communal pathways.5 Several studies have documented that the anti-cancer properties of ORD are due to its apoptosis stimulation effects.15, 21 In agreement with these findings, our results revealed that ORD could initiate apoptosis in PC-3 cells.

Cancer cells are a small population of cells with stem cell features, including self-regeneration, multipotent diversity, increased tumorigenicity, and drug resistance.25, 26 Many dietary compounds, such as curcumin,36 koenimbin,26 sulforaphane,37 and synthetic compounds comprising monobenzylin Schiff base complex,38 have demonstrated the chemopreventive actions of CCs. These cells are recognized as the tumor source and have a crucial role in driving PC development.39 Targeted PCC intermediation may be the ultimate approach to PC prevention and treatment. In this regard, ORD could inhibit tumor conversion and PCC metastasis.40 However, the effects of ORD on PCCs have not been investigated yet. The current study established a concentration-dependent ORD PC-3 cell inhibition and downregulation of markers such as CD133, Oct-4, Nanog, ALDH1A1, and Sox2. These outcomes indicate that ORD could reduce the PCC action and may be proposed as a potential PCC-targeting agent. Indeed, the results from this research highlight the potential role and mechanisms of ORD on PCCs for the first time. Furthermore, we established that ORD anti-proliferative and apoptotic actions on PCCs may be mediated via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an essential role in the growth and expansion of PC cells.28 Also, previous experiments demonstrated that androgen-independent PCC lines, namely the extremely invasive PC-3 cells, display higher Wnt/β-catenin signaling levels than androgen-dependent PC cells.41 The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been documented to be vital for controlling the action of CCs in PC.28, 29 Zhang et al. demonstrated that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its target genes c-myc and cyclin-D1 were stimulated in PCCs.42 In the present research, we investigated if Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in the anti-cancer effects of ORD on PCCs. We found that ORD suppressed GSK3β phosphorylation and the expression of β-catenin, c-myc and cyclin-D1, and inhibited β-catenin nuclear translocation. These findings suggest that stimulation of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by ORD were complemented by the suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. As such, it appears that the proposed anti-cancer actions of ORD on PCCs were mediated through Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Limitations

The current study determined the anti-proliferative actions of ORD on PC-3 cells, highlighted its potent apoptosis-inducing effects, and showed that ORD could suppress CC markers and restrict PC. However, we were unable to uncover novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of ORD in PC.

Conclusions

Oridonin inhibited PC-3 cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in a concentration-dependent way. Moreover, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway appears to be a promising target through which ORD facilitates apoptosis in PC-3 cells. In the current study, we found, for the first time, that ORD controlled Wnt/β-catenin signaling and attenuated PCC activity. According to our findings, ORD has the potential to be a future chemotherapeutic drug, which may decrease drug resistance and PC degeneration by triggering apoptosis in CCs. The findings of this research provide novel insight into the contribution and underlying molecular mechanisms of ORD in PC.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8045766. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Fig. 1. Results of Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 1.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Results of Kruskal–Wallis test as presented in Figure 5.