Abstract

Background. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (hucMSC)-derived exosomes have been reported to be effective in the treatment of cancer. The miR-214-3p is a suppressor miRNA that has been extensively studied and has been proposed as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in some cancers.

Objectives. The aim of this study was to investigate whether the regulatory mechanism of hucMSC-derived exosomal miR-214-3p with GLUT1 and ACLY affects the proliferation and apoptosis of gallbladder cancer (GBC) cells.

Materials and methods. We found that the target genes of miR-214-3p on the TargetScan website contain GLUT1 and ACLY, and the targeting relationship was verified using luciferases. The GBC-SD cells overexpressing GLUT1 and ACLY were constructed to determine proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and other cellular activities.

Results. We identified hucMSCs and exosomes, and found that the exosomes contained miR-214-3p. Furthermore, TargetScan predicted that miR-214-3p had base interactions with ACLY. Dual luciferase assays showed that miR-214-3p could inhibit ACLY (p < 0.05). The results of quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blot showed that exosomal miR-214-3p could inhibit the expression of ACLY and GLUT1 (p < 0.05). Exosomal miR-214-3p can inhibit the proliferation, cloning and migration of GBC-SD cells (p < 0.05). The apoptosis of GBC-SD cells was increased (p < 0.05). The GBC-SD cells overexpressing ACLY and GLUT1 could reverse the efficacy of miR-214-3p.

Conclusions. Exosomal miR-214-3p can inhibit the downstream expression of ACLY and GLUT1. The ACLY and GLUT1 could affect the proliferation and apoptosis of GBC-SD cells.

Key words: GLUT1, exosomes, miR-214-3p, ACLY

Background

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is an uncommon human malignancy that has a particular geographical distribution in Central and South America, Central and Eastern Europe, Japan, and Northern India.1, 2 It is on the rise globally and its prognosis is very poor. Since GBCs are usually asymptomatic, early diagnosis may not be possible.3 Clinical evidence indicates that many GBC patients are diagnosed as inoperable, a state at which the tumor has already become invasive and metastatic.4 The overall prognosis of GBC is extraordinarily poor and the mean survival ranges from 13.2 to 19 months.5 Although some prognostic biomarkers in adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) have shown some promise, the clinical use of these proposed biomarkers has not yet been approved.6, 7 Currently, there are no reliable or acceptable molecular markers associated with simple cholecystectomy (SC) or ASC progression and prognosis.

During oncogenesis, the metabolism of a tumor cell is reprogrammed to support rapid proliferation of tumor cells.8 Previous studies have reported that many metabolic genes play a significant role in the progression of cancer, and can be used as putative biomarkers for prognosis and targets for therapeutic agents. The basic metabolic processes of tumor cells are glycolysis and lipogenesis. It was discovered that most fatty acids in cancer come from lipogenesis.9 Glycolysis is a biochemical process. In cancer cells, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the main energy source.10 Moreover, the fatty acids synthesized in the process of adipogenesis are used as the main fuel for the rapid proliferation of cancer cells to produce cell membranes.11 At present, at least 5 genes in the glycolysis and lipogenesis pathways are directly involved in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. The GLUT1 promotes increased glucose transport in tumor cells and maintains a high glycolysis rate in aerobic conditions. However, ACLY can convert citrate into acetyl-CoA for fat generation as a cell solute enzyme.9 Therefore, GLUT1 and ACLY are known as key enzymes in the rate-limiting first step of the metabolic pathway. In various tumors, such as breast cancer,12, 13 colorectal cancer,14, 15 gastric cancer,16, 17 hepatocellular cancer,18, 19 and prostate cancer,20, 21, 22 GLUT1 and ACLY are upregulated. In this regard, we further explored whether GLUT1 and ACLY play a role in the life activities of cholangiocarcinoma cells.

The human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (hucMSC)-derived exosomes (hucMSC-exo) exert anti-inflammatory effects on human trophoblastic cells by transferring miRNAs.23 The miR-214 was reported to be a member of a vertebrate-specific miRNA precursor involved in regulating glucose metabolism in the liver.24 It also has an important role in skeletal diseases.25 The miR-214-3p is a suppressor miRNA that has been extensively studied and has been proposed as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in some cancers.26

Objectives

Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate whether the regulatory mechanism of miR-214-3p with GLUT1 and ACLY affects the proliferation and apoptosis of GBC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell transfection

Human gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells (BNCC100091) were purchased from Beina Biological Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The required si-RNA-negative control (NC), si-GLUT1 and si-ACLY were removed, and ice thawing was performed. Two of the 8 sterile centrifuges were taken, and 95 μL of serum-free 1640 medium was added to each tube. Then, 5 μL of i-RNA-NC and 5 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 were added to the centrifuges, respectively. Another si-RNA was added to the corresponding centrifuge tube in the same way. The mixture was gently mixed and left to stand for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the 2 tubes were gently mixed and left to stand for 20 min at room temperature. Finally, the mixture was evenly added to the wells to be transfected and mixed. All plasmids were purchased from HonorGene Company (Changsha, China).

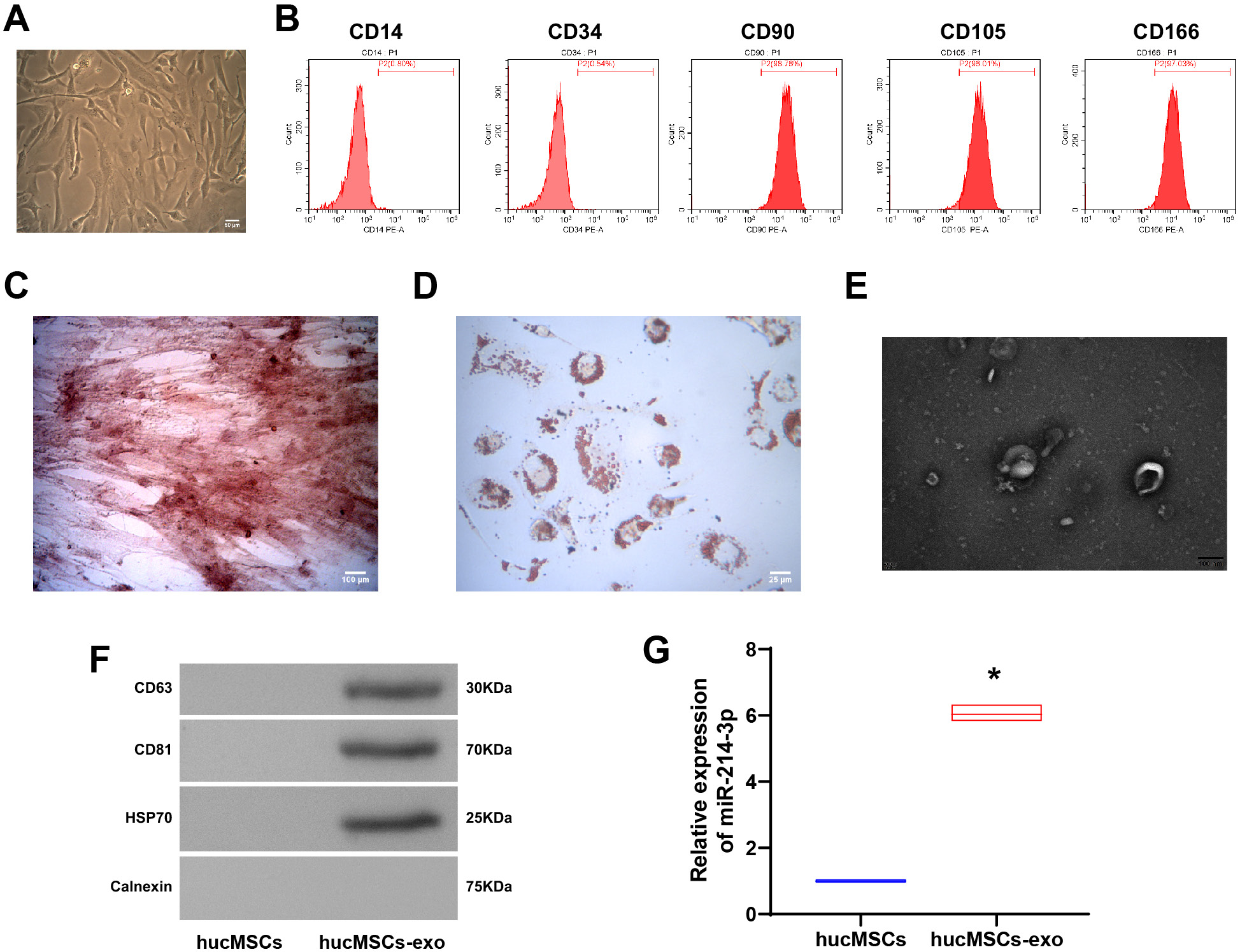

Separation of exosomes

The hucMSCs were obtained from the umbilical cord tissue of newborns. Five cell surface markers (CD105, CD90, CD34, CD14, and CD166) were evaluated to identify hucMSCs. The hucMSCs were counted to ensure that each cell suspension had more than 1 × 106 cells. The cells were incubated with human anti-CD105 (P-phycoerythrin (PE)), anti-CD90 (PE), anti-CD34 (PE), anti-CD14 (fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)), and anti-CD166 (FITC) (all from eBioscience, San Diego, USA), respectively, for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were washed and suspended for flow cytometry analysis. Half the volume of an exosome separation solution was added to the supernatant, blown, mixed, and placed in the refrigerator at 4°C overnight. After 12 h, the supernatant was centrifuged for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant solution was discarded, and the precipitate was retained. The precipitate was blown with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fully mixed to form an exosome suspension. The concentration of exosomes was detected with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein concentration and stored at −80°C as reserve. The effective storage time of exosomes was 1 month.

Identification of exosomes

The exosomes were identified with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (TecnaiTM G2 Spirit BIOTWIN; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). A volume of 20 µL of exosomes was dropped onto the copper mesh and left for 3 min. The cells were dried with an incandescent lamp, and pictures were taken under the TEM. The particle size analysis was performed using a nanoparticle tracking analysis (NS300; Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Western blot was utilized to identify the surface markers of exosomes. The protein content of the exosome suspension was measured with the use of a BCA kit (23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific), the sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel was prepared, protein denaturation and electrophoresis were performed, and the membrane was transferred to detect the exosome-specific marker protein HSP70 (ab5439, 1:1000), CD63 (ab134045, 1:2000), CD81 (ab79559, 1:1000), and calnexin (ab22595, 1 µg/mL; Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Alizarin red S assay

Oligodendrocyte Medium (OM) was used to culture 2 × 104 cells for 7 days. Then, the cells were stained with alizarin red and quantitatively analyzed. A nitrotetrazolium Blue chloride (NBT)/5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) staining kit (72091; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, USA) was used for alizarin red staining after cell fixation. The alizarin red Active Colorimetric Quantitative Detection Kit was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Reagent Company (Nanjing, China). Depending on the instructions, the cells were collected, separated at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and observed with Triton-X100 or X400. The optical density (OD) of cells was measured at 520 nm. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Oil Red O staining

Modified Oil Red O staining solution was used to stain 2 × 104 cells for 10–15 min in airtight conditions, protected from light. Mayer’s hematoxylin staining solution was added to remove the stain, and the nuclei were restained for 5 min. The slices were blotted with filter paper and sealed with glycerol gelatin or gum arabic.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from brain tissues using Trizol (15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

About 500 μL of GBC-SD cells were collected into a new 1.5-mL centrifuge tube, and Trizol was supplemented to 1 mL after mixing, followed by chamber lysis for 3 min. Next, 200 μL of trichloromethane were added into the centrifuge tube, the tube was shaken vigorously for 15 s and then stood at room temperature for 3 min. The concentration was determined with a ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer, the absorbance (OD) value was measured at 260 nm and 280 nm, and the concentration and purity were calculated. Vortex oscillation mixing and temporary centrifugation were used for the wall of the solution to be collected at the bottom of the tube. The solution was incubated for 50 min at 50°C and 5 min at 85°C. Reaction conditions were as follows: 40 cycles of pre-denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, denaturation at 94°C for 15 s and annealing at 60°C for 30 s. After the reaction, the tubes were briefly centrifuged and cooled on ice. The internal reference primer was β-actin. The primer sequences are presented in Table 1. With 2 μg cDNA as template, the 2–ΔΔCt relative quantitative method was used. The relative transcription level of the target gene was calculated as follows (Equation 1,2):

ΔΔCt = Δ experimental group − Δ control group (1)

ΔCt = Ct (target gene) − Ct (β-actin) (2)

Western blot

The GBC-SD cells were extracted using the Total Protein Extraction Solution RIPA kit (R0010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). For primary antibodies, we used rabbit anti-p-mTOR (1:5000, ab109268), mouse anti-mTOR (1:10000, 66888-1-Ig), mouse t anti-p-AKT (1:5000, 66444-1-Ig), rabbit anti-AKT (1:1000, 10176-2-AP), rabbit anti-p-PI3K (0.5 µg/m, ab278545), mouse anti-PI3K (1:800, 67071-1-AP), mouse anti-Bax (1:10000, 60267-1-AP), mouse anti-Bcl-2 (1:1000, 60178-1-AP), rabbit anti-caspase 3 (1:5000, #9661, CST0), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000, 66009-1-Ig). All antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Genomics (San Diego, USA). The membrane was immersed in Superecl Plus (k-12045-d50, Advansta, USA) for the development of luminescence. The β-actin was used as an internal reference. Image J software (NIH, USA) was utilized to analyze gray values.

CCK-8

Cells in each group were counted and inoculated into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well, 100 μL per well. Each group was equipped with 3 multiple holes. After culture and adherence, the treatment was carried out in accordance with the above method. After the corresponding time, 10 μL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (NU679; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well, and the CCK-8 solution was prepared with a complete medium. Then, the drug-containing medium was removed and 100 μL of CCK-8 medium was added to each well. The OD value at 450 nm was analyzed using the BioTek microplate analyzer (DSZ2000X; Cnmicro, Beijing, China) after further incubation at 37°C for 4 h at 5% CO2, and the mean value was drawn as a histogram.

Wound healing assay

A flask of cells was taken and trypsinized, and after counting, approx. 5 × 105 cells were added to each well. After the cells were covered with the plate, the pipette tip was used to draw a horizontal line perpendicular to the previously drawn horizontal line. Cells were washed 3 times with sterile PBS, streaked cells were removed, and serum-free 1640 medium (R8758; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was added. The scratches were photographed at 0 h, and 3 fields of view were taken at each timepoint. After culturing at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h and 48 h, pictures were taken again for recording.

Double luciferase activity

The target gene analysis of ACLY with miR-214-3p was performed using TargetScan website (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80) to verify whether there is a targeting relationship between ACLY and miR-214-3p using the luciferase reporter gene assays. The target gene ACLY dual luciferase reporter gene vector and mutants with mutations of the binding site of miR-214-3p (pGL3-ACLY Wt and pGL3-ACLY Mut) were constructed, respectively. Two reporter plasmids were co-transfected with the overexpression of miR-214-3p into cells, and 24 h after transfection, the cells were lysed according to the TransDetect® Double-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit procedure (FR201-01; full-form gold; Antipedia, Beijing, China), and the supernatant was collected. After that, 100 μL of luciferase reporter gene activity (Renilla luciferase) was added to Reaction Reagent II and the ratio of firefly luciferase to sea kidney luciferase (FL/RL) was used to determine relative luciferase activity. Each experiment was repeated 3 times.

Cell colony formation

Cells from each group of the p-index growth phase were taken, digested with 0.25% trypsin, blown into individual cells, and suspended in a complete medium with 10% calf serum. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and saturated humidity for 2–3 weeks, with appropriate fluid changes. The culture medium was discarded, and the PBS solution (SH30256.01; HyClone, Logan, USA) was carefully washed twice. The 6-well plate was removed and soaked with 1 mL of 10% acetic acid to decolorize. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (MB-530; Huisong Pharmaceuticals, Hangzhou, China).

Flow cytometry analysis

The cells were collected using digestion with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free trypsin. They were washed twice with PBS and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min each time to collect approx. 3.2 × 105 cells. Next, 500 μL of binding buffer was added to suspend the cells. After adding 5 μL of Annexin V-APC, 5 μL of propidium iodide (MBC0409; Meilunbio, Wuhan, China) was added, mixed at room temperature and protected from light. The reaction was performed for 10 min within 1 h and detected with flow cytometry.

The fixed sample was taken out, centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Then, 1 mL of pre-cooled PBS was added to resuspend the cells, centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min, and the cells were collected by centrifugation. Next, 150 μL of propidium iodide working solution was added and stained at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. The percentage of each cell cycle on the fluorescence histogram was analyzed.

Transwell assay

The cells treated above were digested with trypsin to form single cells, resuspended in serum-free medium to 2 × 106 cells/mL, and 100 μL of cells were added to each well. The upper chamber was taken out and placed in a new well containing PBS. The pore size was 8 μm. The samples were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (G1062; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 5 min, washed with water 5 times, placed on a glass slide, and photographed under a microscope (model DSZ2000X; Cnmicro). The cells on the outer surface of the upper chamber were observed under an inverted microscope (model DSZ2000X; Cnmicro), and 3 fields of view were taken for each. The chamber was taken out and soaked in 500 μL of 10% acetic acid to decolorize, and the OD value was measured with a microplate reader (DSZ2000X; Cnmicro) at 550 nm.

Statistical analyses

All measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD). The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v. 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test and F-test were used to compare variances and to evaluate whether the data conformed to a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance assumption. The unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the data between 2 groups that did not have one-to-one correspondence. The Shapiro–Wilk test and the Brown–Forsythe test were used to analyze whether the data conformed to a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance assumption. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test were used to compare data among 3 groups. The measurement data obeyed the normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. The degrees of freedom and p-values for normal distribution were used to present the results of the analysis. The difference was statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Identification of hucMSCs and exosomes

First, we performed cultures on the purchased hucMSCs. The cells showed shuttle-shaped, swirling growth (Figure 1A). Flow cytometry was used to detect the cell surface antigens CD14 (0.80%), CD34 (0.54%), CD90 (98.76%), CD105 (96.01%), and CD166 (97.03%) (Figure 1B). The hucMSCs showed osteogenic capacity (Figure 1C) and lipogenic capacity (Figure 1D). Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe the secretion of exosomes by huc-MSCs (TecnaiTM G2 Spirit BIOTWIN; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Exosomes were collected and were positive for exosome markers CD63, CD81 and HSP70, and negative for calnexin and elevated miR-214-3p expression (Figure 1E–G). All raw data are presented in Supplementary Table 1. In short, hucMSCs can secrete exosomal miR-214-3p.

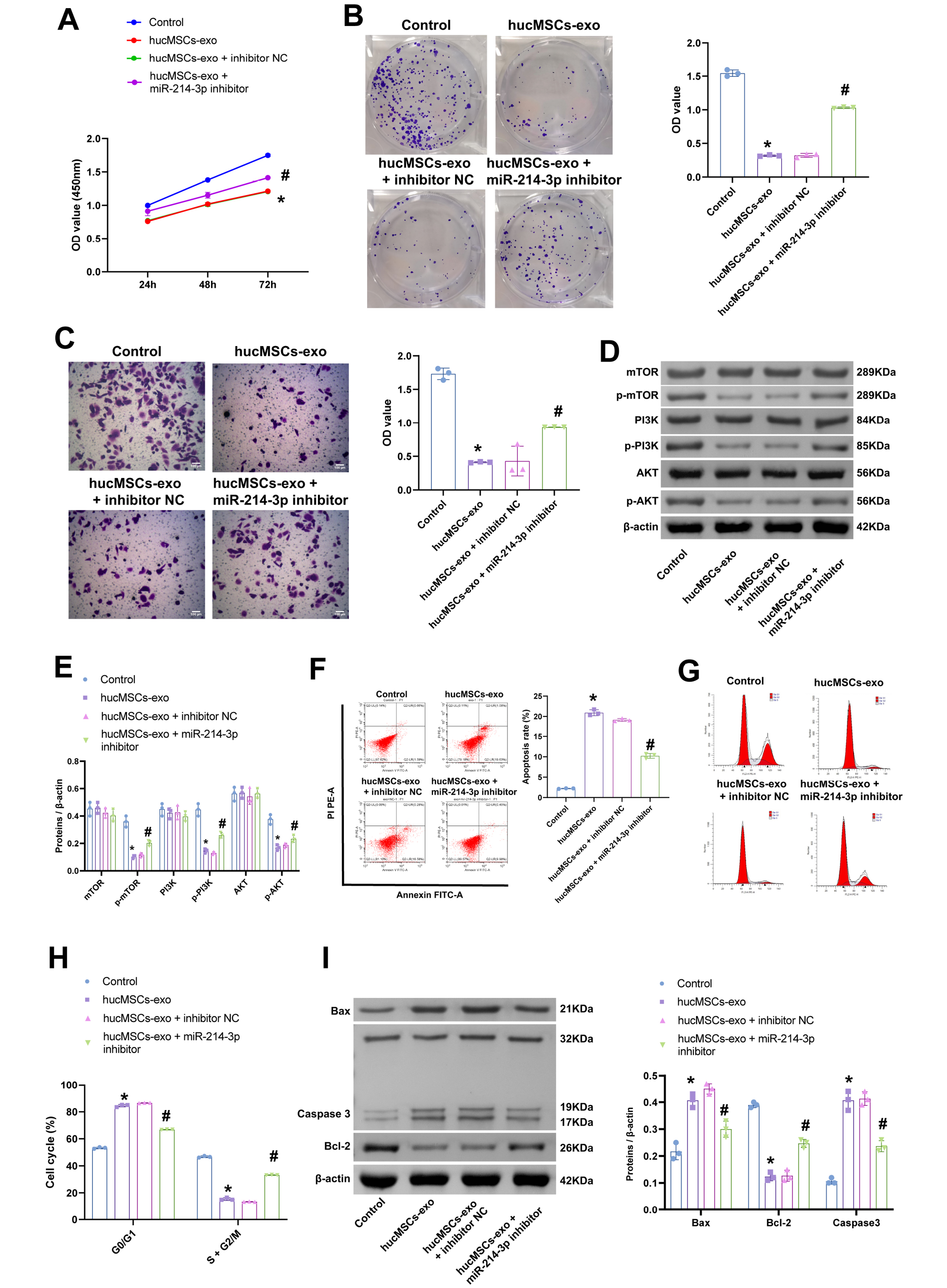

Exosomal miR-214-3p can affect the proliferation of GBC-SD

The above results indicated the presence of miR-214-3p in hucMSC exosomes. To investigate the effect of exosomal miR-214-3p on the development of cholangiocarcinoma, the GBC-SD cell line was selected for subsequent experiments. The addition of exosomes in GBC-SD resulted in a decrease in cell proliferation (Figure 2A), clonogenic ability (Figure 2B), invasive ability (Figure 2C), and an increase in the percentage of apoptosis (Figure 2F) and G0/G1 phase (Figure 2G,H). In contrast, after miR-214-3p silencing in GBC-SD, the proliferative, clonogenic and invasive capacities of the cells significantly increased after the addition of the exosomes in GBC-SD, while the percentage of apoptosis and S-phase decreased. The levels of p-mTOR, p-PI3K, p-AKT (Figure 2D,E), and Bcl-2 decreased, and the expression of Bax and caspase 3 increased under exosome intervention. Silencing of miR-214-3p increased the levels of p-mTOR, p-PI3K, p-AKT, and Bcl-2, and inhibited the expression of Bax and caspase 3 (Figure 2I). The data displayed in Figure 2 are also presented in Supplementary Table 2. In short, miR-214-3p in exosomes was able to inhibit the proliferation of GBC-SD cells.

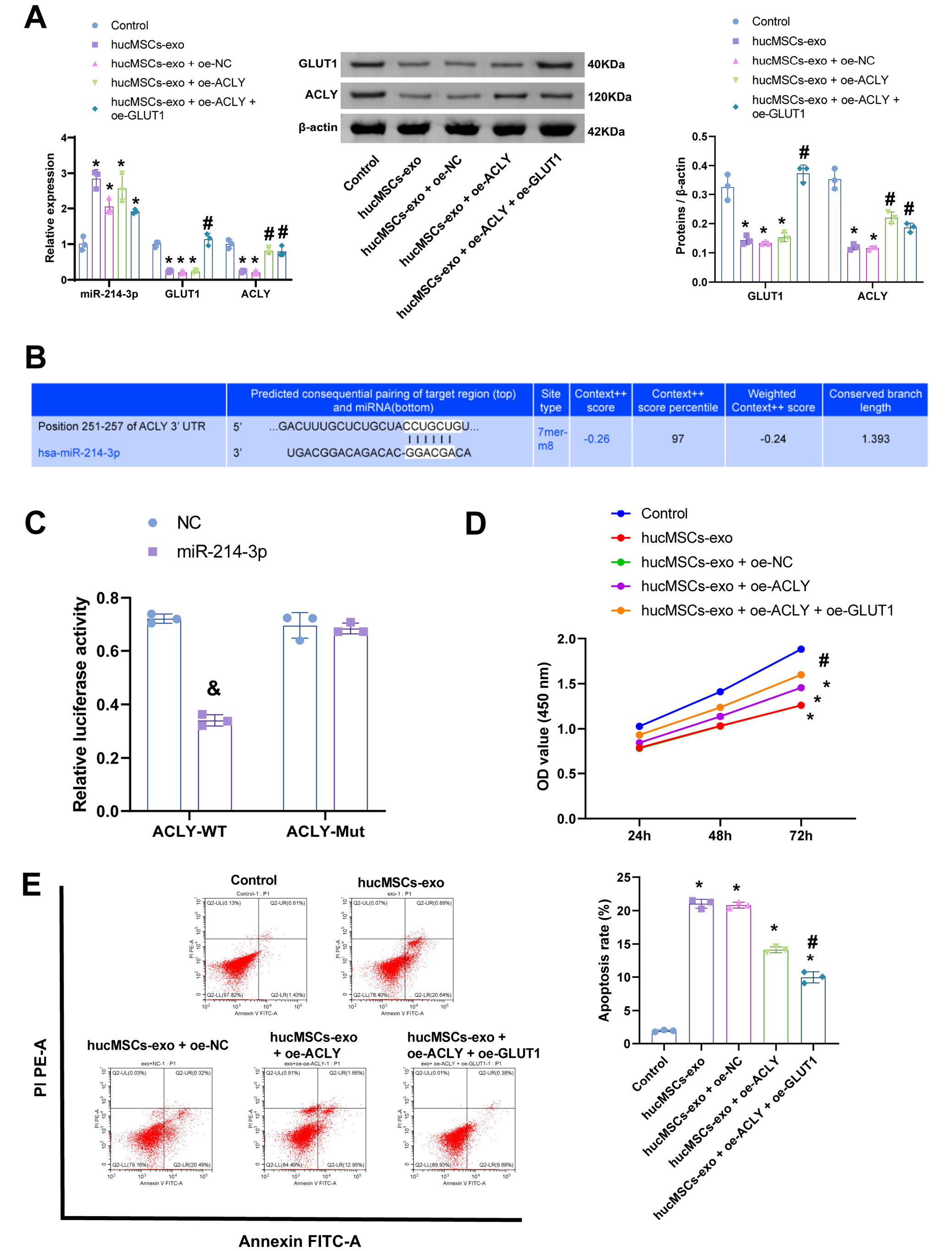

Exosomal miR-214-3p can regulate ACLY/GLUT1 to affect GBC-SD cells

The above experiments demonstrated that miR-214-3p can affect the proliferation and apoptosis of GBC-SD cells in exosomes. To investigate whether miR-214-3p can regulate the progression of GBC through ACLY/GLUT1, we constructed cell models overexpressing ACLY and GLUT1. The miR-214-3p expression levels were not affected by the overexpression of ACLY and GLUT1. Exosomal miR-214-3p inhibited ACLY and GLUT1 expression (Figure 3A,B). The miR-214-3p was shown to have base interactions on the TargetScan website (https://www.targetscan.org/; Figure 3C). Dual luciferase activity assays showed that miR-214-3p can target and inhibit the expression of ACLY (Figure 3D). The data showed that exosome-competent miR-214-3p inhibited the proliferation of GBC-SD cells (Figure 3E) and promoted their apoptosis (Figure 3, Figure while the overexpression of ACLY and GLUT1 cells reversed this effect. The source data and analysis results of Figure 3 are presented in Supplementary Table 3. In short, ACLY and GLUT1 can affect the proliferation and apoptosis of GBC-SD cells.

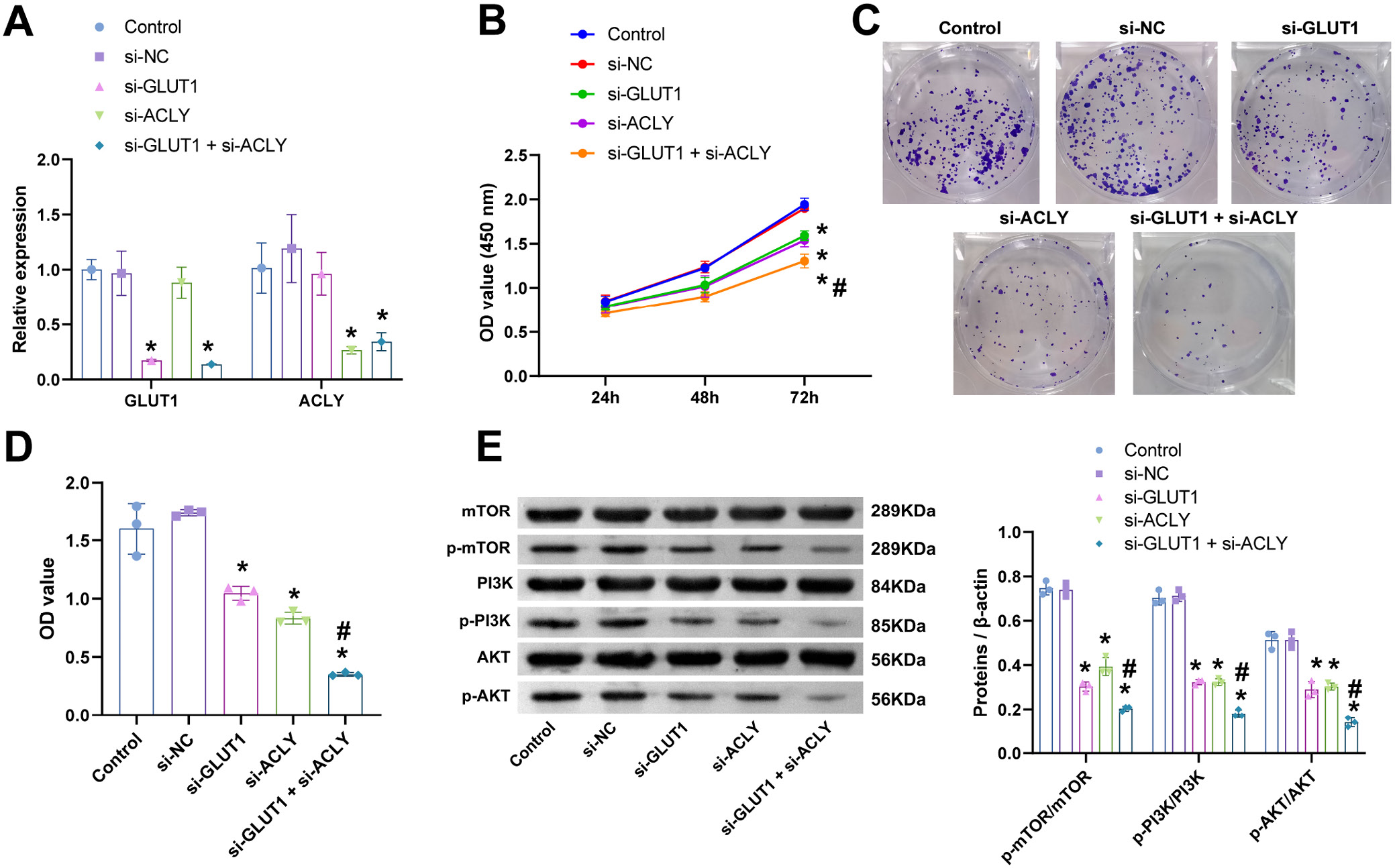

Inhibition of GLUT1 and ACLY can affect the proliferation of GBC-SD cells

The above results showed that GLUT1 and ACLY were associated with the prognosis of GBC patients. We planned to investigate whether GLUT1 and ACLY could affect the function of GBC-SD in vitro. Firstly, we constructed GBC-SD cells with the silencing of GLUT1 and ACLY. The data presented in Figure 4A showed that the expression of GLUT1 and ACLY was inhibited in GBC-SD cells after silencing, indicating that the cell model was successfully constructed. Compared with the control and si-NC groups, the proliferative and clonogenic abilities of GBC-SD cells were reduced in the si-GLUT1 and si-ACLY groups, and the proliferative and clonogenic abilities of GBC-SD cells were more significantly reduced in the si-GLUT1+si-ACLY group (Figure 4B–D). Then, we examined the expression of proliferation-related genes, and the expression of p-mTOR, p-PI3K and p-AKT was significantly reduced in GBC-SD cells silenced with GLUT1 and ACLY (Figure 4E). The results of the data analysis displayed in Figure 4 are presented in Supplementary Table 4. In short, silencing of GLUT1 and ACLY inhibited the proliferative capacity of GBC-SD cells.

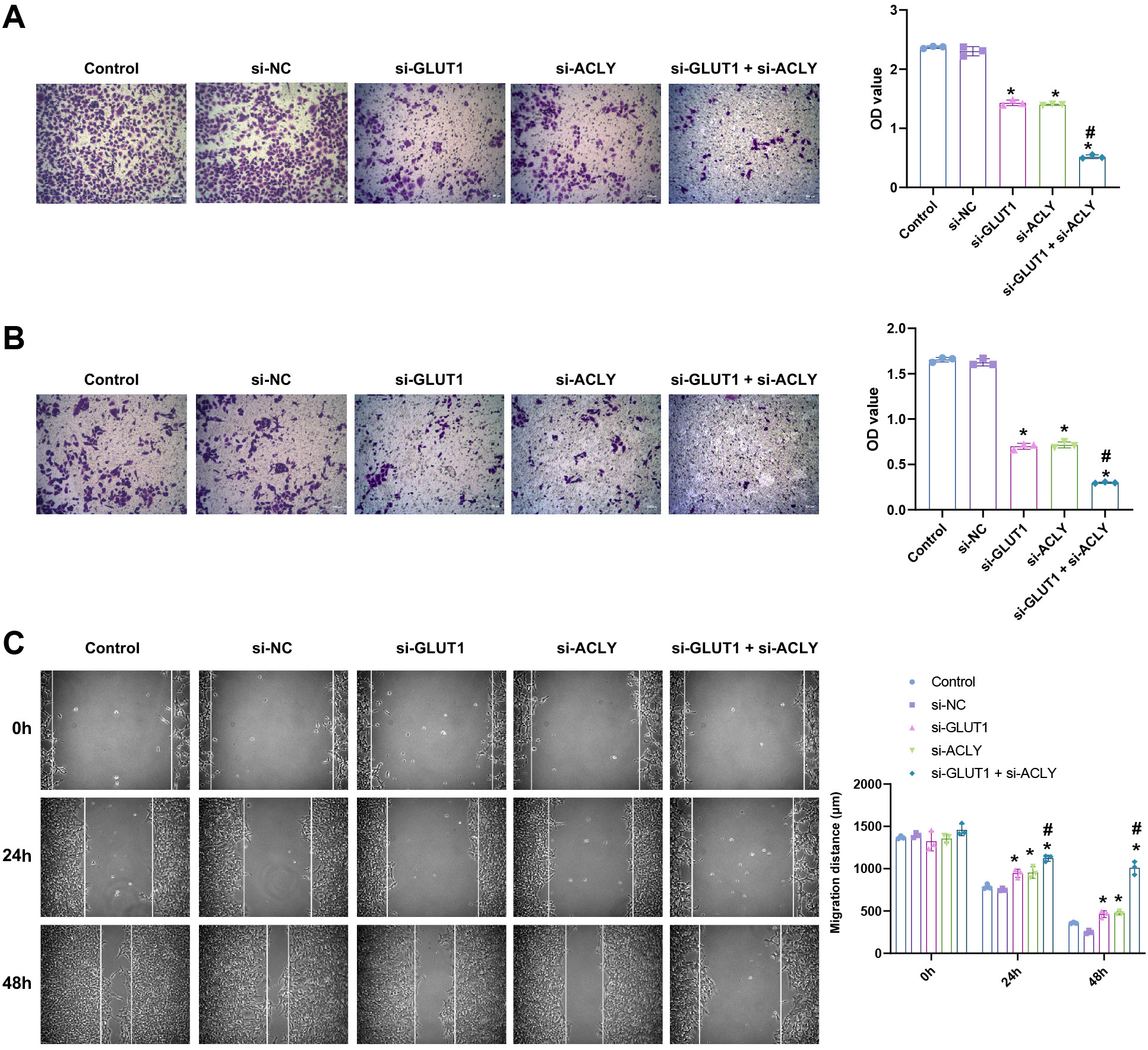

Inhibition of GLUT1 and ACLY can affect GBC-SD cell migration

The above results suggested that GLUT1 and ACLY can affect the proliferation of GBC-SD cells, thus whether silencing GLUT1 and ACLY can inhibit the proliferation of GBC-SD cells required further study. Transwell assays were used to detect the migration and invasion ability of GBC-SD cells. The experimental results demonstrated that the migration and invasion ability of GBC-SD cells were reduced in the si-GLUT1 and si-ACLY groups compared to the control and si-NC groups, and the reduction of migration and invasion ability of GBC-SD cells was more significant in the si-GLUT1+si-ACLY group (Figure 5A,B). The scratch assays were performed to measure the migration distance, and the migration distance of GBC-SD cells silenced with GLUT1 and ACLY was significantly lower (Figure 5C). The results displayed in Figure 5 are presented in Supplementary Table 5. In conclusion, silencing of GLUT1 and ACLY inhibited the migratory ability of GBC-SD cells.

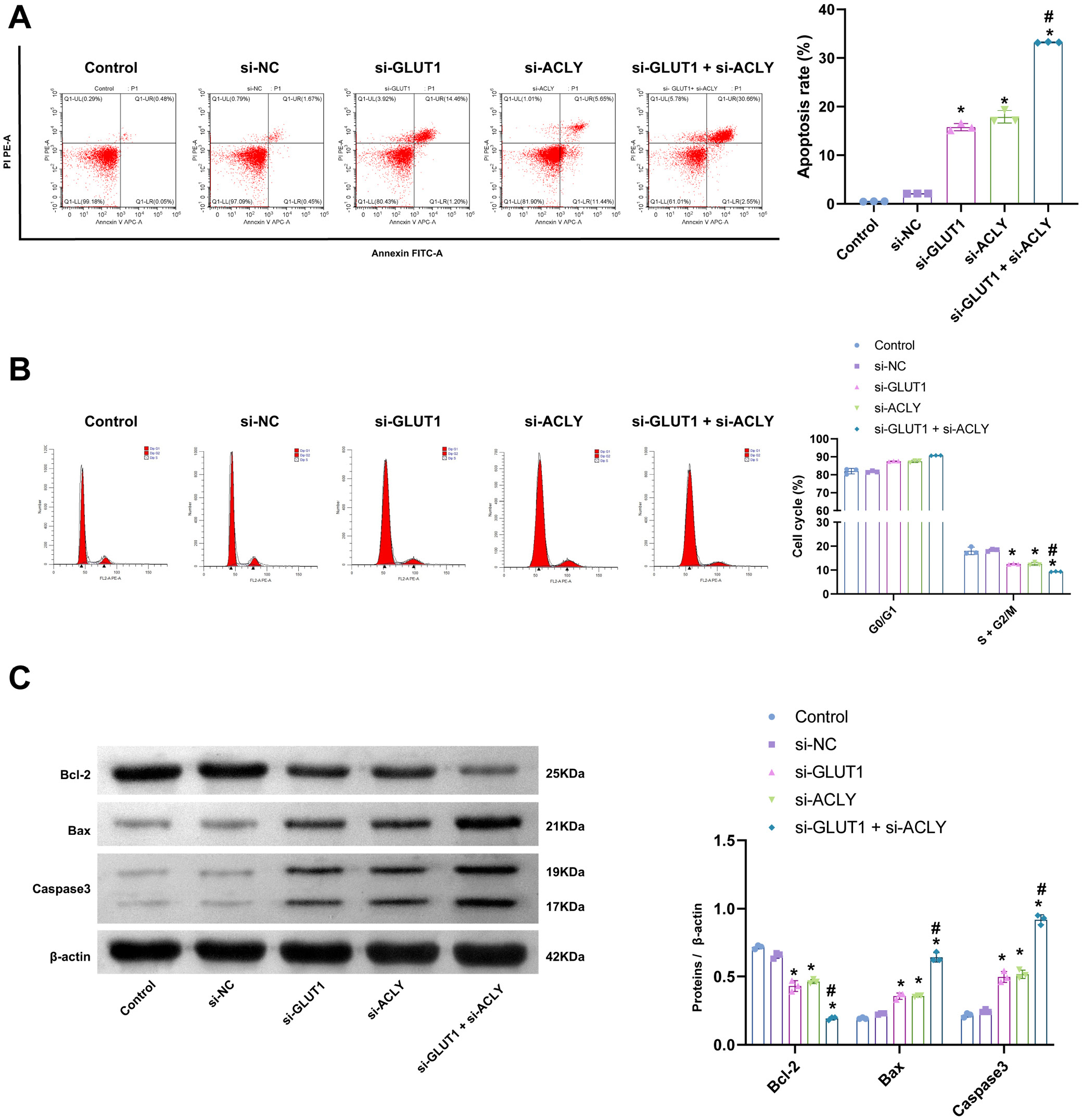

Inhibition of GLUT1 and ACLY can affect the apoptosis of GBC-SD cells

The above results suggested that GLUT1 and ACLY can affect the proliferation and migration of GBC-SD cells; thus, whether the silencing of GLUT1 and ACLY can promote apoptosis of GBC-SD cells required further investigation. Flow cytometry was used to detect the apoptosis rate of GBC-SD cells. Compared to the control and si-NC groups, the apoptosis rate of GBC-SD cells was elevated in the si-GLUT1 and si-ACLY groups, and the increase in the GBC-SD cell apoptosis rate was more significant in the si-GLUT1+si-ACLY group (Figure 6A). The results of the data in Figure 6B showed that the sum of S and G2/M phases of GBC-SD cells in the si-GLUT1 and si-ACLY groups were decreased compared to the control and si-NC groups, and the sum of S and G2/M phases of GBC-SD cells in the si-GLUT1+si-ACLY group was decreased more significantly. Western blot was utilized to analyze the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. The expression of Bax and caspase 3 was significantly increased, while the expression of Bcl-2 was significantly decreased in GBC-SD cells silenced with GLUT1 and ACLY (Figure 6C). The results displayed in Figure 6 are presented in Supplementary Table 6. All in all, silencing of GLUT1 and ACLY promoted apoptosis in GBC-SD cells.

Discussion

The understanding of clinicopathological characteristics of SC/ASC derives from studying the cases and analyzing small groups of patients. Therefore, more comprehensive studies are necessary to accurately understand SC/ASC tumors and adenocarcinoma differences. In malignant tumors of the gallbladder, the squamous differentiation incidence is at 1–12%.6 In this study, we observed that ACLY with GLUT1 reversed the inhibition of GBC-SD cell proliferation and migration by exosomal miR-214-3p.

Exosomes are subsets of naturally occurring particles inside the cells, with notable functions during physiological and pathological conditions.27 Recent data revealed that exosomes facilitate paracrine cell-to-cell communication via the transfer of different biomolecules.28 Evidence points to the fact that these nanoparticles can deliver numerous biotherapeutic agents to the target cells by using different fusion mechanisms and ligand–receptor interactions.29 Exosomes can act as biological shuttles and can even treat neurological damage.30 The SFB-miR-214-3p exosomes suppressed apoptosis and inflammation in chondrocytes.31 The overexpression of miR-214-3p repressed proliferation and cancer cell stemness in vitro and in vivo in squamous cell lung cancer via targeting YAP132 and fibroblast growth factor/MAPK signaling.33 Han et al. suggested that miR-214-3p modulated breast cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis by targeting Survivin.34 The miR-214-3p also interacted with TWIST1 to suppress the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of endometrial cancer cells.35 In our study, exosomal miR-214-3p inhibited the proliferation and migration of GBC-SD cells and promoted their apoptosis. Exosomal miR-214-3p can reduce the activity of GBC-SD cells. This may have significant efficacy in treating the progressive development of GBC.

The ACLY is an enzyme that has recently been proven to be the key to the metabolism of cancer cells.8, 36 The ACLY is the main source of acetyl-Coenzyme A, an important precursor for fatty acid, cholesterol, and isoprenoid biosynthesis, and it is also involved in protein acetylation.37 The activation of ACLY signaling is linked to many cancers, such as prostate cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, leukemia, glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, and liver cancer.21 A positive expression of GLUT1 significantly predicts a poor prognosis in lung cancer patients. The GLUT1 may serve as a helpful biomarker and a potential target for the treatment strategies of lung cancer.38 The blocking of ACLY by siRNA can inhibit the Akt pathway, resulting in tumorigenicity loss in vitro. It is believed that blocking the ACLY pathway may have the potential to treat cancers. The results of this study showed that the knockdown of ACLY and GLUT1 inhibited the proliferation of GBC-SD cells and promoted apoptosis.

Limitations

It is thought that specific blocking of the GLUT1 and ACLY pathways may have the potential to treat human cancers. We will explore the effects of GLUT1 and ACLY on animal and human GBC in the future.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that exosomal miR-214-3p can target and inhibit ACLY. The miR-214-3p can inhibit the proliferation of GBC-SD cells. The overexpression of GLUT1 and ACLY promoted the proliferation of GBC-SD cells. In vitro experiments revealed that miR-214-3p can interfere with the activity of GBC-SD cells by inhibiting ACLY, which provided a basic theory for the treatment of GBC.

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8161958. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. The expression of miR-214-3p.

Supplementary Table 2. The proliferation and apoptosis of GBC-SD cells.

Supplementary Table 3. miR-214-3p can regulate ACLY/GLUT1 to affect GBC-SD cells.

Supplementary Table 4. Inhibition of GLUT1 and ACLY could affect the proliferation of GBC-SD cells.

Supplementary Table 5. GLUT1 and ACLY could inhibit the migratory ability of GBC-SD cells.

Supplementary Table 6. GLUT1 and ACLY could affect the apoptosis of GBC-SD cells.