Abstract

Background. Osteosarcoma is a pleomorphic cancer that frequently affects children and teenagers. Although several chemotherapy regimens have been utilized for many years, the best therapeutic option for the treatment of osteosarcoma has not yet been determined.

Objectives. This meta-analysis was designed to assess the clinical efficacy of a high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MAP) regimen and compare its survival outcomes with those of other chemotherapy strategies in patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma.

Materials and methods. We systematically searched databases, namely Embase, the Cochrane Library and PubMed, up to August 2022, for relevant studies investigating the impact of the MAP chemotherapy protocol on survival among patients with osteosarcoma. The odds ratio (OR) pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated.

Results. Twelve studies including 4102 patients were eligible for analysis in this study. The estimated pooled ORs of the 3-year overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) were OR = 1.08 (95% CI: 0.72–1.62, p = 0.70) and OR = 1.04 (95% CI: 0.81–1.32, p = 0.78, respectively). The 5-year OS and EFS were OR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.62–1.23, p = 0.42) and OR = 1.13 (95% CI: 0.76–1.68, p = 0.54), respectively, with no statistical differences. The subgroup analysis of MAP compared to a 2-drug regimen (doxorubicin and cisplatin) revealed a significant difference between the 2 chemotherapy strategy groups in 3-year OS rates (OR = 0.72 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92, p = 0.009)) and 5-year EFS rates (OR = 0.57 (95% CI: 0.43–0.76, p < 0.001)).

Conclusions. The MAP chemotherapy strategy for osteosarcoma showed superiority over other regimens, especially over the 2-drug regimen (doxorubicin/cisplatin), in terms of better prognosis and safety.

Key words: doxorubicin, overall survival, cisplatin, osteosarcoma, ifosfamide

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is a pleomorphic malignancy that commonly occurs in children and adolescents. It is defined as a primary malignancy of the mesenchymal tissues in bones and accounts for 20–40% of all diagnosed bone cancers.1 The etiology of osteosarcoma remains unknown; however, exposure to radiotherapy, alkylating agent-based chemotherapy, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, and Paget’s disease of bone are considered risk factors and account for a proportion of the cases.2 The main treatment approach for this type of bone cancer was amputation, which had limited clinical efficacy. Chemotherapy and surgical strategies were introduced in the 1970s and improved the overall 5-year survival rate to about 70%.3 During that time, chemotherapy was used postoperatively to eliminate unresectable lesions. Later, preoperative chemotherapeutic regimens were clinically applied and known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This approach was widely adopted in clinical practice since it helped in the elimination of potential micro-metastases, reduced tumor edema, increased limb salvage rates, reduced recurrence rates, and improved the overall survival (OS) rates.4

In the past decades, a number of trials have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of different postoperative chemotherapeutic agents. Initially, methotrexate was reported, followed by other agents with some degree of survival improvement.5, 6 The studied drugs included ifosfamide, dacarbazine, and their combination with doxorubicin, with a response rate reaching up to 40%. Single-agent chemotherapy has been shown to be inadequate for osteosarcoma treatment. A trial conducted in 2014 comparing doxorubicin alone with its combination with ifosfamide revealed a significant improvement in the rates of progression-free survival (PFS) and the overall response for the combined chemotherapeutic regimen. However, the OS between the 2 regimens did not significantly differ (p = 0.076).7 Recently, as approved by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines,8, 9 the most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents for osteosarcoma include doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and ifosfamide.

Nowadays, novel approaches are applied for osteosarcoma management, including targeted drug therapy, experimental therapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy. The combination of up to 4 drugs, namely doxorubicin, methotrexate, cisplatin, and ifosfamide, is the main osteosarcoma treatment in today’s protocols.6, 9, 10 The recommended regimens, according to the NCCN guidelines, include a doxorubicin and cisplatin combination; high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MAP) combination; methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and ifosfamide (MAPI) combination; and ifosfamide, cisplatin and epirubicin combination.9 Most healthcare settings worldwide conduct a number of preoperative chemotherapy courses, ranging from 2 to 6 courses for up to 18 weeks.11 The toxicity of chemotherapeutic regimens should also be considered, which includes bone marrow suppression, neurological toxicity, liver and kidney damage, and gastrointestinal disorders. Although these regimens have been used for many years, the optimal therapeutic choice for osteosarcoma treatment has not been established.

Objectives

Therefore, studies that compared the above regimens were eligible for the present meta-analysis to establish a detailed comparison between the available regimens and assess the clinical efficacy and toxicity of first-line chemotherapeutic agents for patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and identification

This meta-analysis was designed and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The ethical approval was waived due to the type of the study. The protocol of this meta-analysis has been registered in PROSPERO as CRD42022385111. Original research studies written in English and published up to August 2022 were verified by the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library databases. The keywords or medical subject headings (MeSH) terms related to osteosarcoma, chemotherapy, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, ifosfamide, and survival rate were combined during the database search, as presented in Table 1. The retrieved studies were carefully investigated for eligibility. Only human research studies were included. Irrelevant publications, assessed on the basis of the title, abstract or full article, were excluded. Also, commentaries, review articles, editorials, and irrelevant studies were all excluded. All chosen publications were collected using EndNote software (Clarivate, London, UK), and duplications were excluded.

Inclusion criteria

The current meta-analysis inclusion criteria were:

1. Well-designed randomized controlled or comparative studies, either prospective or retrospective;

2. Studies in which the intended target patients were those with a confirmed diagnosis of osteosarcoma using typical imaging or pathological biopsy;

3. Studies in which the procedure of intervention included a comparison of the first-line chemotherapeutic regimens, according to the NCCN recommendations for the treatment of osteosarcoma;

4. Studies in which data were adequately described to estimate the overall pooled effect size of the intervention and 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

The exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were:

1. Reports, editorials, abstracts, reviews, animal experiments, and studies in languages other than English;

2. Publications with missing or incomplete outcomes;

3. Research articles with aims other than the examination of the recommended first-line chemotherapeutic regimens such as target receptor-based therapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and vaccine-based therapy.

Data extraction

The methodological quality was evaluated and data extraction was performed by 2 independent authors, according to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines.12 We used a pre-designed form to summarize the study- and participant-related variables under the following headings: the name of the first author, study period, region, target patients, study protocol, number of subjects, demographical characteristics, applied chemotherapeutic protocol, and survival status. The main outcome measures included the OS rate, which is the time elapsed from the inclusion in the study to death or the last follow-up; event-free survival (EFS), which is the time from the inclusion in the study to metastatic disease appearance or death; and the total number of adverse effects (grade ≥3) after the implementation of different chemotherapeutic regimens. The targeted adverse effects included neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, cardiac and renal dysfunction, mucositis, and anemia.

Risk of bias

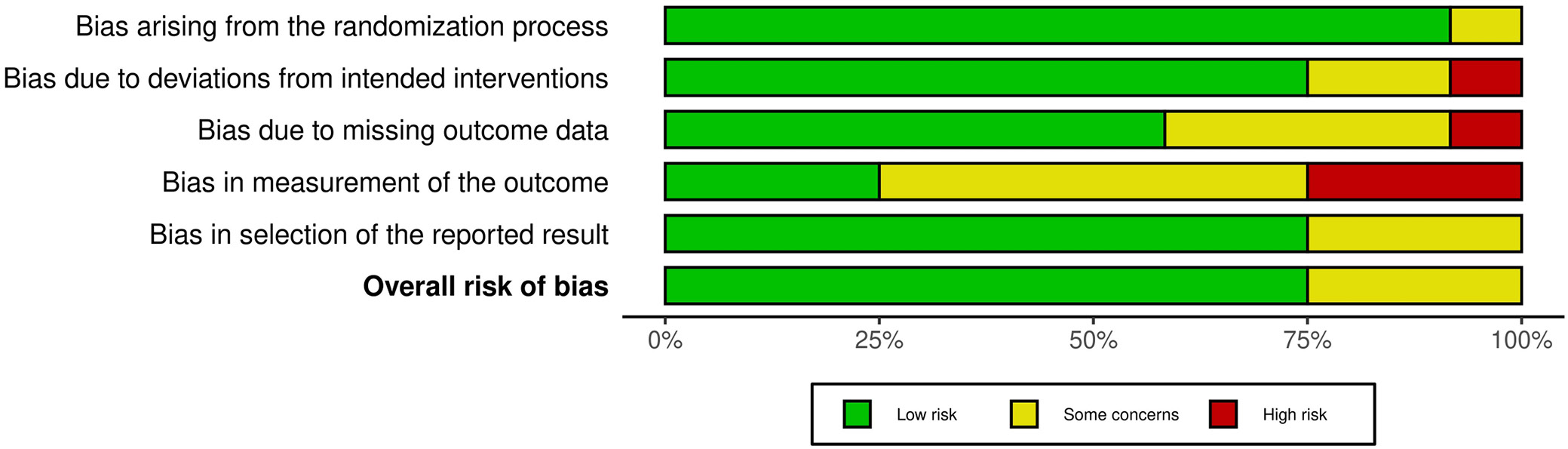

Following data extraction, the authors assessed the quality of the chosen studies according to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. The risk of bias was graded as low, medium or high, and was assessed based on the employed randomization method, the outcome assessment blinding, and any missing data or selective reporting. We reviewed the original article to clarify any discrepancies or misunderstandings.

Statistical analyses

The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were computed using fixed- or random-effect models. The pooled estimates of the interventions’ effect sizes and graphs were performed using the Reviewer Manager (RevMan) software v. 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). The χ2 tests were utilized to test for heterogeneity. The estimated I2 index ranged between 0% and 100% and was used to evaluate heterogeneity.13 When the value of the I2 index was 0%, it was interpreted as an absence of heterogeneity, an I2 index of 25% was identified as a low level of heterogeneity, and the values of 50% and 75% were identified to represent moderate and high heterogeneity levels, respectively. If the I2 index was higher than 50%, we applied a random-effect model, and if it was less than 50%, we applied a fixed-effect model. The sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the source of significant incoherence for the main outcomes. The value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. The assessment of bias was quantitatively performed using the Egger’s regression test (p ≤ 0.05 denoted bias between studies), and qualitatively, by visual inspection of the funnel plots.

Results

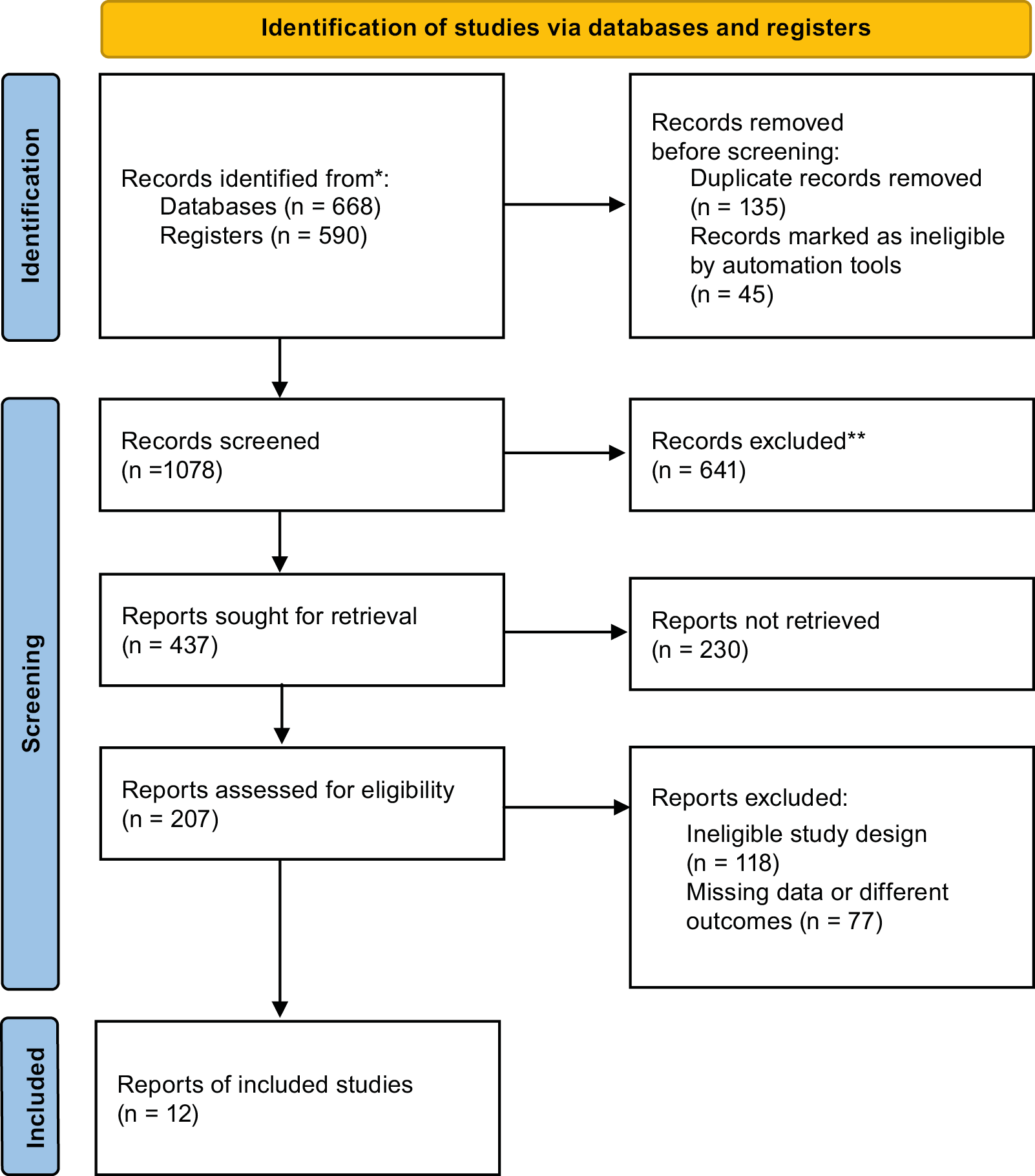

A total of 1258 potential publications were retrieved through a database search. After full-text assessment, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated in this meta-analysis.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The process of literature search and screening is depicted in Figure 1. The selected studies involved a total of 4102 patients. All included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The sample size of the integrated studies ranged from 36 to 716 osteosarcoma patients at the beginning of the trial. The main features of the selected studies are summarized in Table 2.

The risk of bias in the eligible studies was evaluated according to the Cochrane Collaboration tool (Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2)). All included trials adequately described the randomization procedures, while blinding and allocation concealment were variable. The evaluation of the risk of bias is summarized in Figure 2.

Overall survival rates

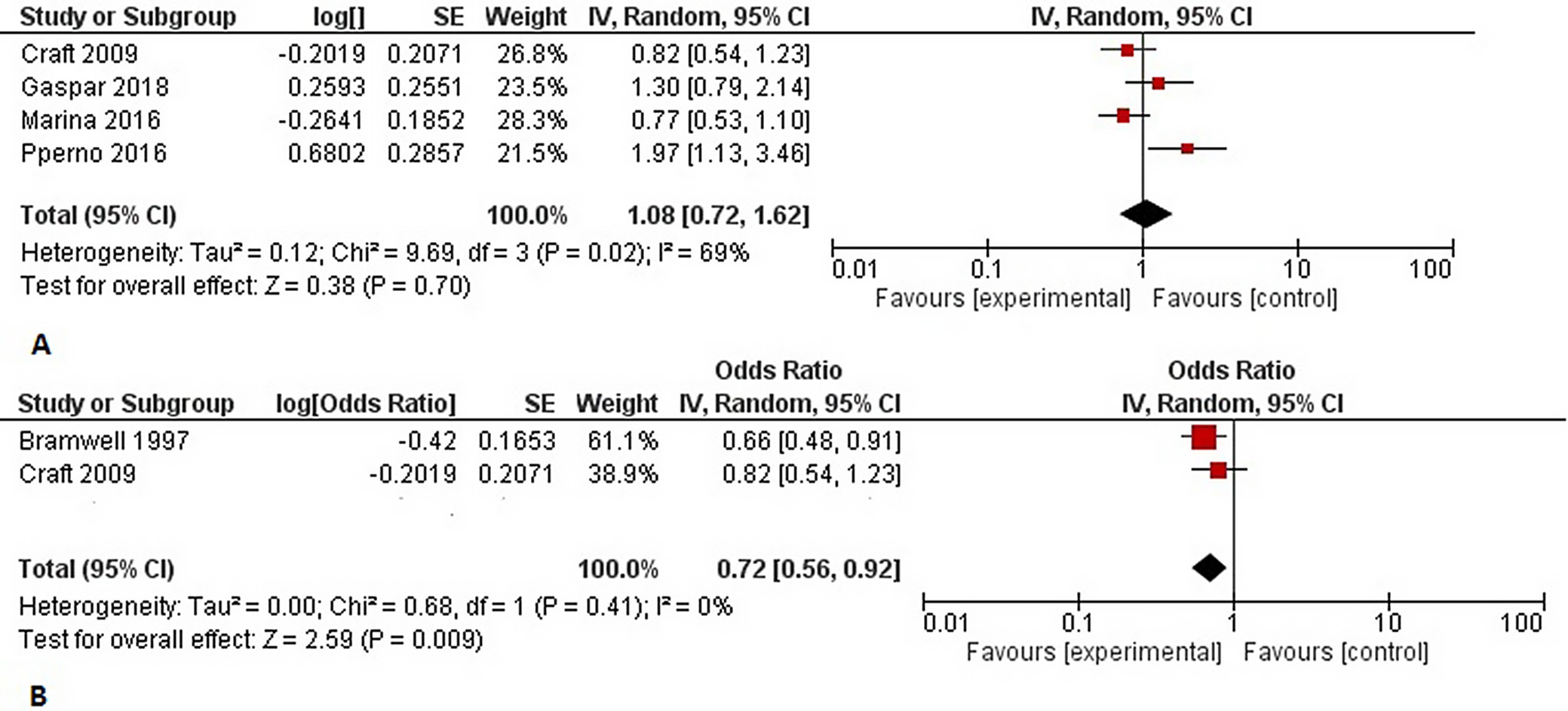

Four studies (n = 1886) reported data related to the 3-year OS rates. The comparison of MAP with different therapeutic regimens, including doxorubicin and cisplatin regimens or MAP chemotherapy regimens plus adjuvant drugs, showed no differences between groups (OR = 1.08 (95% CI: 0.72–1.62), Z-test = 0.38, p = 0.700), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 69%), as shown in Figure 3A. The subgroup analysis of the pooled OR of the survival rate with MAP chemotherapy compared to doxorubicin and cisplatin combination chemotherapy revealed a significant difference between the 2 groups regarding 3-year OS rates (OR = 0.72 (95% CI: 0.56–0.92), Z-test = 2.59, p = 0.009) (Figure 3B).

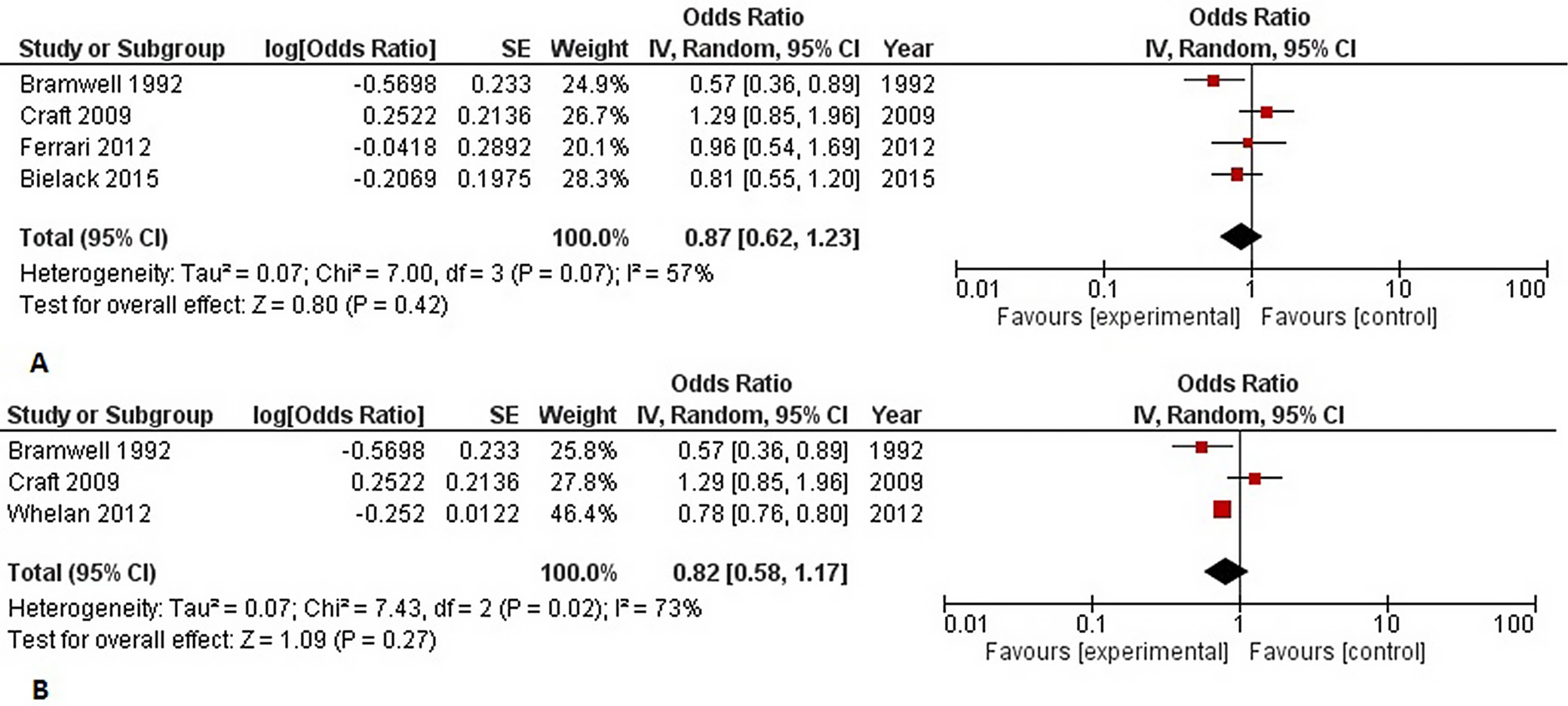

The 5-year OS rate was assessed in 4 studies (n = 1657). The forest plot, presented in Figure 4A, summarizes the overall ORs with non-statistically significant differences between the arms of comparison (OR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.62–1.23), Z-test = 0.80, p = 0.420). Moderate heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 57%). The subgroup analysis of the 5-year OS rate after MAP chemotherapy compared to doxorubicin and cisplatin combination chemotherapy revealed a non-statistically significant difference (OR = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.58–1.17), Z-test = 1.09, p = 0.270), with moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 73%, χ2 = 7.43, p = 0.020) (Figure 4B).

Event-free survival rates

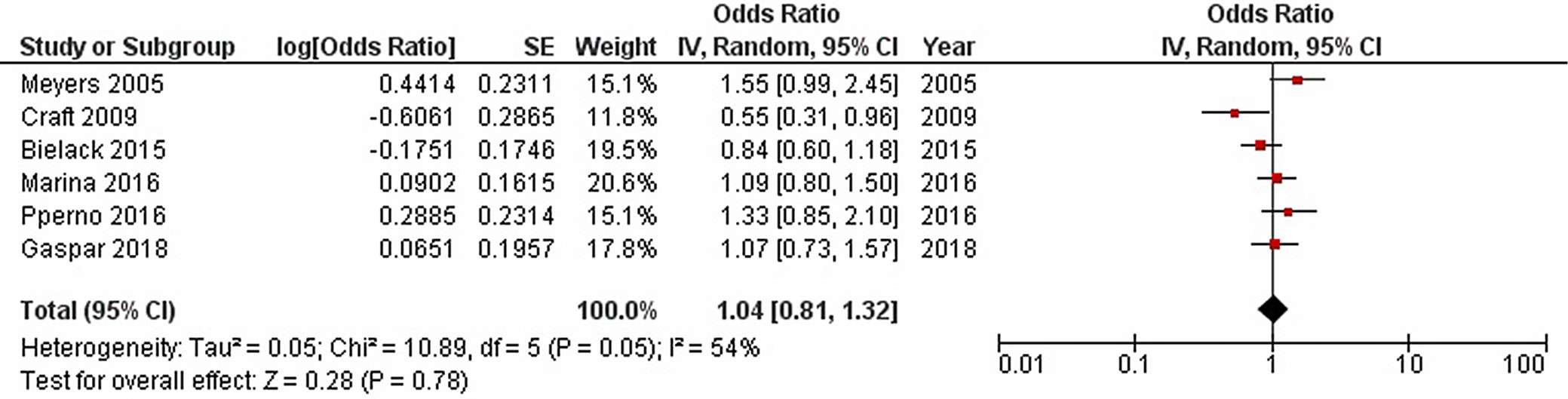

Six studies (n = 3001) reported data related to the 3-year EFS. The comparison of MAP chemotherapy regimens with other regimens revealed no significant differences, with an overall OR of 1.04 (95% CI: 0.81–1.32, Z-test = 0.28, p = 0.780). The estimated heterogeneity between studies was moderate (I2 = 54%) (Figure 5).

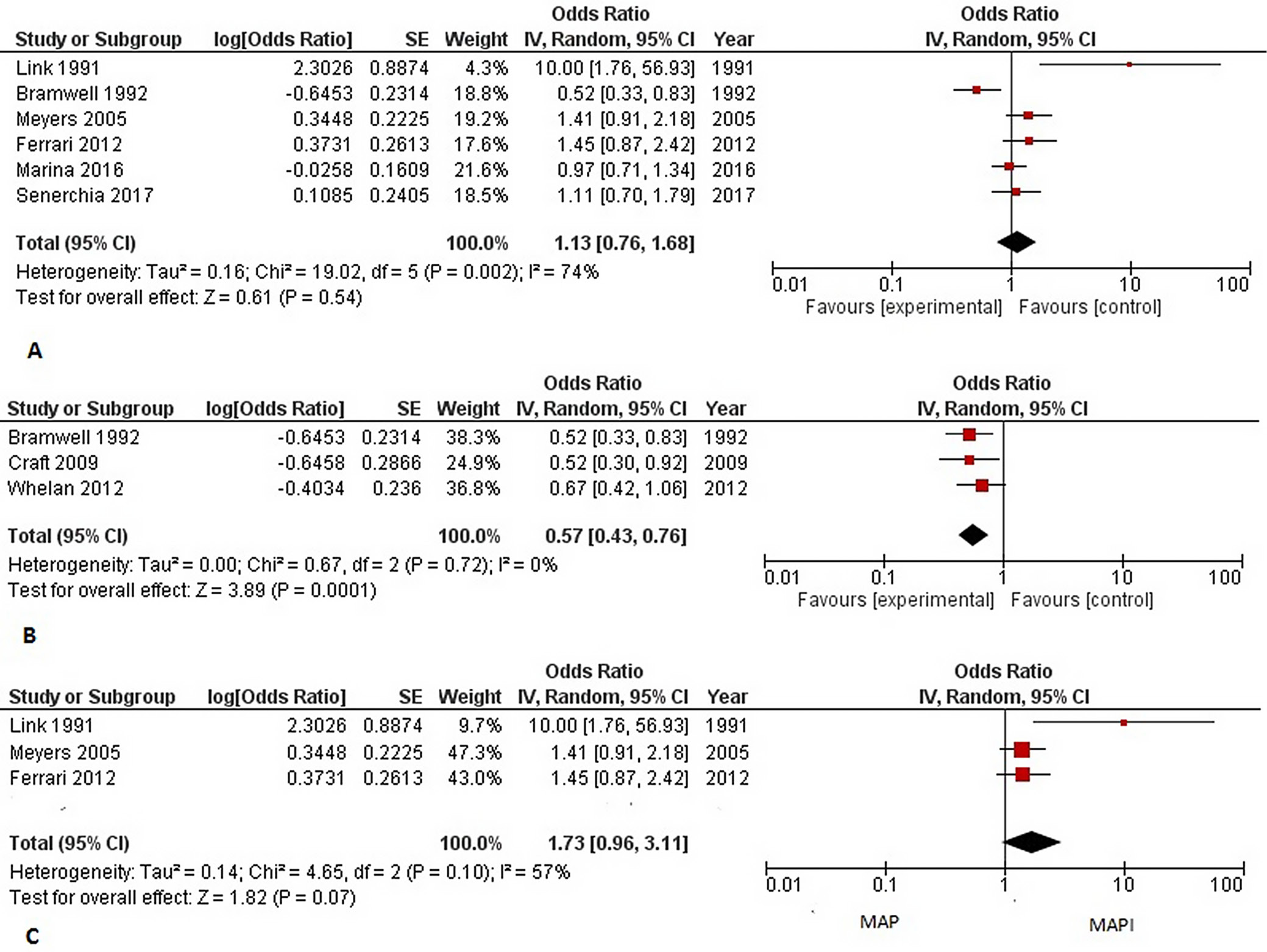

The 5-year EFS rate was reported in 6 studies (n = 1902). The estimated 5-year EFS rate was 61.2% (1164/1902) with the use of MAP regimens compared to the other chemotherapeutic regimens. The forest plot, as shown in Figure 6A, revealed non-significant differences between the comparison groups (OR = 1.13 (95% CI: 0.76–1.68), Z-test = 0.61, p = 0.540) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 74%). The subgroup analysis of the pooled OR of the 5-year EFS rate with MAP chemotherapy compared to 2-drug combinations, doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy, revealed a significant difference between the 2 groups in 5-year EFS rates (OR = 0.57 (95% CI: 0.43–0.76), Z-test = 3.89, p < 0.001) (Figure 6B). The comparison of MAP regimen with MAPI revealed preferable 5-year EFS rates with the addition of ifosfamide, as shown in Figure 6C. However, the overall OR was statistically non-significant (OR = 1.73 (95% CI: 0.96–3.11), Z-test = 1.82, p = 0.070), with moderate heterogeneity (χ2 = 4.65, p = 0.100, I2 = 57%). The adjustment for factors such as gender, race, and age, as well as subgroup analysis were not conducted because of the limited data on the influence of these variables in the included studies. We assessed the impact of each study on the overall results using sensitivity analysis. The symmetrical shape of the funnel plots and the results of Eggers’s test, as illustrated in Table 3, did not show any evidence of publication bias.

Overall severe adverse effects and systemic toxicities

The chemotherapy-related toxicities are summarized in Table 4. Seven common adverse effects of chemotherapy were observed in the eligible studies. These included neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hypophosphatemia, cardiac toxicity, mucositis, and anemia. Neutropenia events were the most common, with an incidence rate of 87.4% (615/703) for MAP or MAPI regimens and 92.9% (416/448) for other chemotherapy regimens. The thrombocytopenia incidence rate was lower for the MAP or MAPI regimen (69.1% (484/700)), compared to other combinations of chemotherapy (78.9% (355/450)). The incidence rates for febrile neutropenia and anemia were lower for MAP or MAPI regiments compared to other chemotherapy combination regimens: 62.8% compared to 79.5% and 70.2% compared to 81.6%, respectively.

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is the most prevalent bone tumor in the young age group, with a high mortality rate and the risk of metastasis to other organs, commonly the lymph nodes and lungs, in about 30% of patients.26 Multi-drug combination chemotherapy and surgery have been associated with improved survival rates of up to 80%.9, 27 The frontline chemotherapy combination for osteosarcoma treatment includes high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin and doxorubicin with or without ifosfamide. However, the overall efficacy of this regimen is still controversial in many RCTs. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the latest meta-analysis on the effectiveness and tolerability of first-line chemotherapy combination drugs for osteosarcoma.

This meta-analysis included 12 RCTs with a total of 4102 patients. The outcomes for the 3- and 5-year OS and EFS were used for efficacy assessment. The total number of severe adverse events was evaluated as a measure of the safety and tolerability of different chemotherapeutic regimens. Based on the conducted analysis, no significant difference was observed in the survival rate between MAP and other regimens. These results are consistent with a recently published meta-analysis by Yu et al.28 However, the subgroup analysis showed that the MAP regimen significantly improved 3-year OS and 5-year PFS when compared to the doxorubicin and cisplatin combination. Consistent with our results, Bacci et al. reported significant survival benefits with a methotrexate-based regimen among patients with osteosarcoma.29 High-dose methotrexate seems to play a pivotal role in the efficacy of the multi-drug combination regimen; however, its exact mechanism has not yet been clarified.30 Ifosfamide, a cyclophosphamide analog, is a highly effective therapeutic agent in osteosarcoma treatment. In our results, the comparison of MAP with MAPI revealed a favorable 5-year event-free prognosis with the addition of ifosfamide to the regimen, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.070). The relatively small number of the included studies could have prevented the detection of significance. A meta-analysis conducted by Fan et al. reported a reduced mortality rate of about 17% and remarkable responses with a chemotherapeutic regimen based on ifosfamide.31

According to our results, the MAPI regimen could significantly improve the survival rates of patients with osteosarcoma compared to the 2-drug chemotherapeutic regimen (doxorubicin and cisplatin). Furthermore, MAPI showed better outcomes compared to the MAP regimen; however, the difference was non-significant.

Although the MAP regimen, with or without ifosfamide, showed better responses and prognoses in patients with osteosarcoma, its adverse effects are also a matter of concern. The safety assessment of MAP and MAPI chemotherapy-based regimens showed lower rates of toxicities, including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, febrile neutropenia, hypophosphatemia, cardiac toxicity, mucositis, and anemia. These results are consistent with the meta-analysis by Yu et al., which reported lower rates of adverse effects with MAP-based regimens, especially with regards to febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and hypophosphatemia.28 The combination of both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimens with surgery has become the major strategy for osteosarcoma treatment.32 The addition of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before resection has many advantages, including better control of the primary tumor, reduced metastasis incidence, and early assessment of the prognosis. Several studies have confirmed a similar efficacy with MAPI as neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy regimen.32, 33

This meta-analysis had numerous strong points. First, this is the latest meta-analysis on the efficacy and safety of the first-line regimens of chemotherapy for osteosarcoma treatment. Second, we explored the efficacy of the ifosfamide addition to the MAP regimen, and we compared the 2-drug regimen, cisplatin/doxorubicin, with the methotrexate-based multi-chemotherapy regimens. Third, the absence of publication bias was evident qualitatively, after visual inspection of the funnel plot, and quantitatively, after conducting the statistical test for publication bias. Besides, our findings provide clear and concise evidence for the efficacy and safety of osteosarcoma chemotherapy.

Limitations

Nonetheless, the present meta-analysis had some limitations. The main limitation of the study was the use of evidence with potential bias. Some of the included RCTs did not adequately describe the allocation and blinding techniques, which might affect the validity of the findings. Second, the lack of adjustment to the confounding factors could affect the overall outcomes. Besides, some comparisons included a small number of studies; therefore, further studies are warranted to develop the optimum strategy for osteosarcoma treatment and prognosis.

Conclusions

The MAP chemotherapy regimen for osteosarcoma showed superiority over other regimens, especially over the 2-drug regimen (doxorubicin/cisplatin) for osteosarcoma treatment in terms of better prognosis and safety.