Abstract

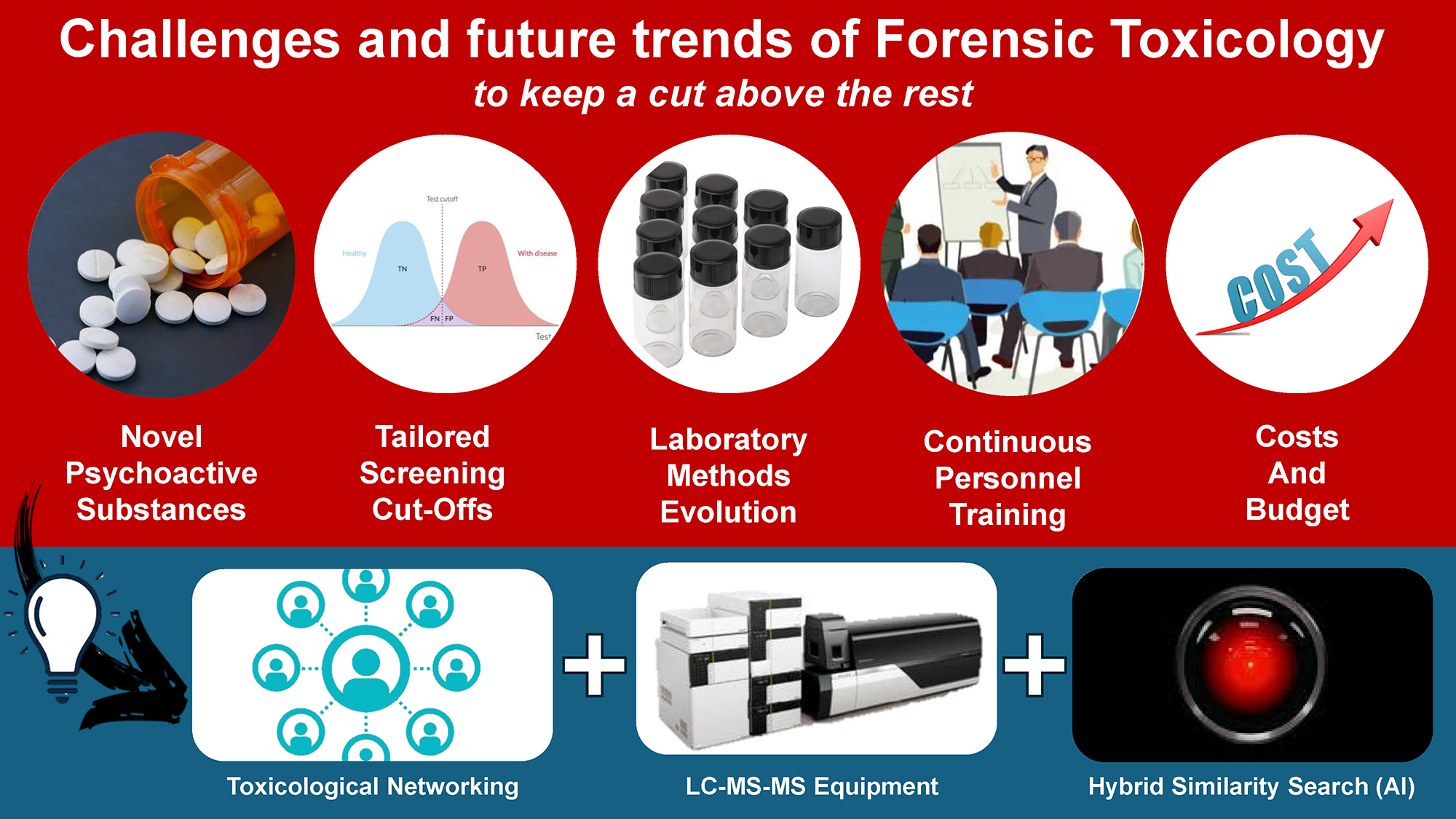

Forensic toxicology faces several challenges in research and daily practice, including new drugs and futuristic technologies requiring innovative testing methods and continuous education and training of professionals. One of the most pressing issues in recent years is the emergence of novel psychoactive substances, often created by modifying the chemical structure of existing drugs to produce compounds with similar effects that are not yet regulated and lack standardized references. To overcome this challenge, forensic toxicologists have employed a range of analytical methods, including qualitative and quantitative analysis using highly sensitive technologies such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), which are the most reliable and accurate methods for detecting drugs in biological samples. Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) is becoming the gold standard for detecting controlled substances, their derivatives and metabolites. Despite advancements in testing methods, challenges persist in forensic toxicology. As such, the field must invest in research and development to improve testing methods, utilize cutting-edge technologies, increase funding for training programs, and promote multidisciplinary interactions.

Key words: forensic toxicology, forensic medicine, mass spectrometry, chromatography, immunoassay

Introduction

Forensic toxicology is an essential field that plays a pivotal role in solving crimes, ensuring public safety and monitoring social phenomena of substance abuse, even in young people.1, 2 However, the field encounters several challenges and innovations in research and daily forensic practice, including the emergence of new drugs that activate specific interconnected metabolic systems in the human brain, cutting-edge technologies requiring new testing methods, and the need for continuous education and training of professionals to keep up with these developments.3

Techniques in use

In recent years, forensic toxicology has faced the increasing prevalence of novel psychoactive substances (NPS). A lack of standardized references and the emergence of new substances pose a challenge for forensic toxicologists in identifying and quantifying NPS in bodily fluids. To overcome this issue, the systematic application of mass spectrometry (MS)-based technologies is required, and forensic toxicology laboratories must maintain the highest scientific integrity in their analytical processes. Immunoassay (IA) was the traditional standard for screening purposes, followed by MS for confirmation analysis. However, gas and liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS and LC-MS) have grown in popularity over time. These methods can analyze many molecules at low concentrations in one run, making them useful for clinical applications, including therapeutic drug and psychoactive substance abuse monitoring, forensic investigations and anti-doping controls.4

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, in particular, has become crucial to the field, replacing immunoenzymatic methods for screening and confirmation.5, 6 The method has higher analytical specificity and sensitivity than IA, which may suffer from calibration bias, diminished sensitivity and specificity, and potential vulnerability to various interferences. The accuracy of IA can also be compromised by cross-reactivity with endogenous and exogenous compounds linked to the analyte of interest, leading to incorrect positive or negative results. Moreover, inconsistency across platforms is a pressing concern, as the impact of cross-reactivity relies heavily on the antibodies used. Experts recommend using hyphenated MS techniques to overcome the limitations of immunoassay-based screening methods, especially in systematic toxicological analysis and drug abuse testing.7 However, challenges such as high instrument costs, personnel qualification requirements and longer processing times hinder the implementation of MS techniques. More user-friendly and fully automated MS instruments should be used to address these issues. Nonetheless, due to fast sample preparation and analysis, IA is still widely used in routine laboratory practices.

In toxicology workflows, a confirmation technique is only used after a positive result from a screening technique, particularly for forensic applications. As a consequence, negative outcome of a screening technique must be reliable to a near-certainty. On these bases, forensic toxicology laboratories need to optimize screening cutoffs for specific case scenarios rather than relying solely on manufacturer’s recommendations, as recently published.8

Recent developments

Forensic toxicology has been prioritizing the development and validation of techniques for detecting an ever-growing number of “classic drugs” and NPS in biological samples taken from living and deceased individuals.9, 10 A range of analytical methods have been implemented to identify and characterize NPS. Among these, qualitative and quantitative methods, such as LC-MS and GC-MS, are considered the most reliable and accurate. However, these techniques are not universally accessible in all forensic toxicology laboratories and require trained operators and continuous updates from national and international networks. Additionally, more cost-effective techniques such as LC-photodiode array and GC-flame ionization detection are employed.

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem MS has emerged as the gold standard analytical tool for detecting controlled substances, their derivatives and metabolites.11, 12 The combination of chromatographic retention time and high-resolution (tandem) MS helps identify a drug molecule by determining the precise mass of a precursor ion and its fragmentation pattern. During the identification process, similarity search algorithms compare the tandem mass spectra of targeted compounds with those in a database. An extensive MS-MS database is crucial for LC-MS-MS-based drug analysis and monitoring, though it is not as comprehensive as required to meet the increasing number of newly synthesized drugs.

Identifying novel synthetic drugs has been one of the most challenging analytical issues in the drug regulatory community. To address this, recent approaches have used artificial intelligence (AI) to study illicit drug analogs, specifically, the hybrid similarity search (HSS).13 Furthermore, NPS analysis requires labor-intensive and expensive reference standards, which might not be accessible for recently emerged NPS on the illicit market. Deep learning methods have been developed to predict known and hypothesized NPS MS/MS spectra from their chemical structures alone.14 However, implementing AI-based technologies in forensic toxicology encounters significant problems, including limited or poor-quality training data that can limit accuracy. Furthermore, biological samples can vary significantly in composition between individuals, making interpreting the results difficult, and if the training data contain biases, AI can inherit and amplify these biases. Data from forensic toxicology laboratories should be collected and integrated to achieve larger and homogeneous datasets, which is particularly relevant if the training data are representative of specific demographic groups or if there are inequalities in the samples. The interpretation of results requires specialized expertise, which means that forensic toxicology often requires the experience of a multidisciplinary team.

Conclusions

The field of forensic toxicology is experiencing a dual challenge. On the one hand, there is a need for highly reliable techniques that can deliver scientifically sound evidence with the utmost precision and accuracy, which are an integral prerequisite in criminal justice proceedings. On the other hand, the illicit market is increasing, bringing a surge of unfamiliar molecules, meaning we must invest in research and development to improve testing methods and the use of cutting-edge technologies. Future research should focus on developing methods for detecting many substances in progressively smaller sample volumes while ensuring the high accuracy and precision levels necessary for forensic analysis.

Sharing data among laboratories by creating national and international networks is crucial to meeting the aims outlined and will require increased funding for training programs and promoting multidisciplinary interactions.15 By doing so, we can support forensic toxicology to achieve and maintain excellence at the highest analytical level. A cut above the rest.