Abstract

Background. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is considered one of the most common causes of irreversible blindness among elderly patients. Neovascular AMD, which accounts for 10% of all AMD cases, can cause devastating vision loss due to choroidal neovascularization (CNV). The clinical effects and safety of intravitreal injection of conbercept in patients suffering from neovascular AMD have not been fully evaluated.

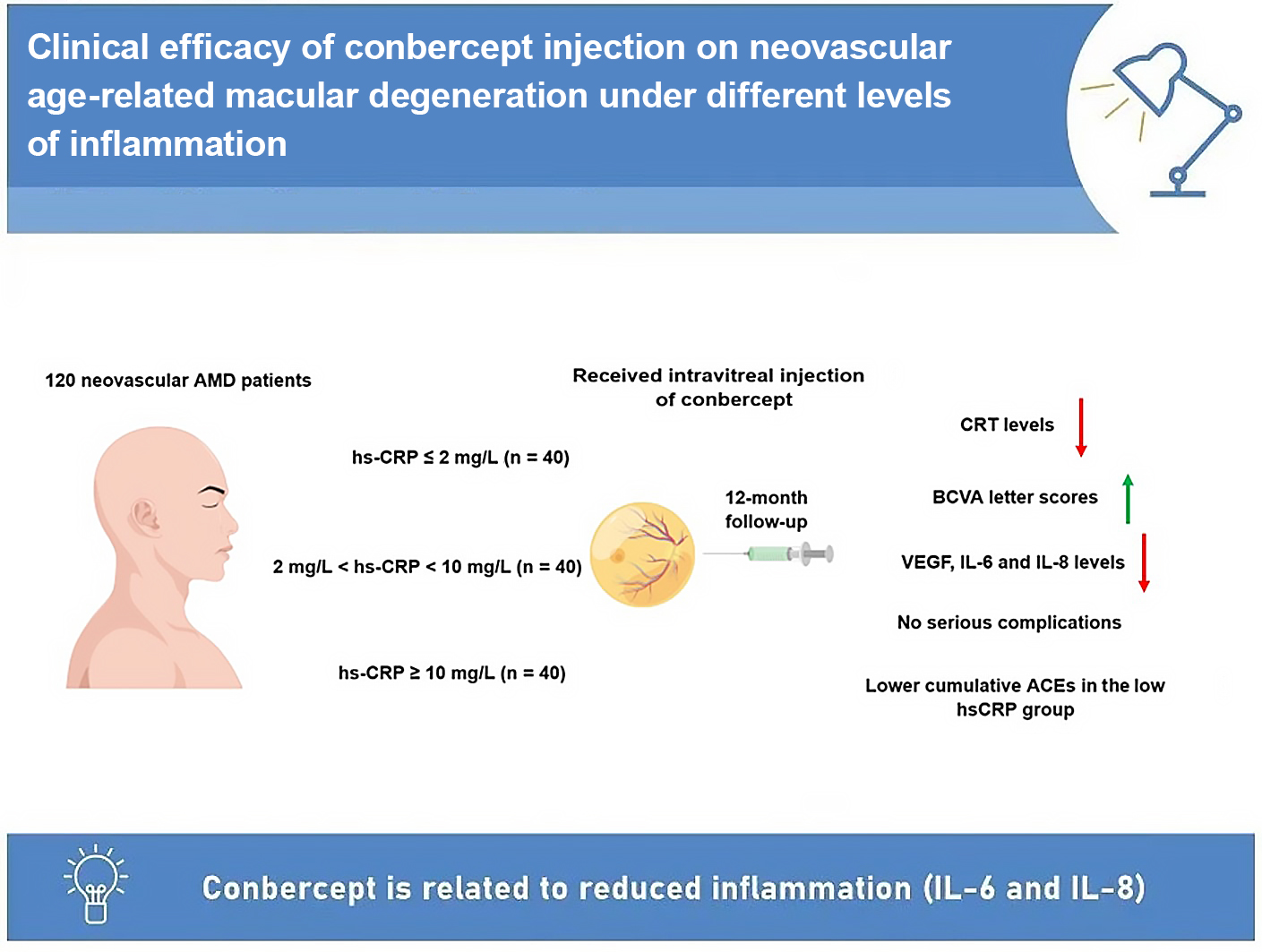

Objectives. The aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravitreal injection of conbercept in patients with neovascular AMD with different levels of inflammation.

Materials and methods. A total of 120 consecutive patients with neovascular AMD who underwent intravitreal injection of conbercept (3 injections per month + pro re nata (3 + PRN)) were included and stratified based on the intraocular level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). The level of inflammation was defined as low, medium or high, based on the concentration of hs-CRP prior to injection. Before and after conbercept injections, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central retinal thickness (CRT) were compared, respectively. Moreover, cytokine markers as well as the frequency of injections and adverse events (AEs) were measured.

Results. There were significant differences in BCVA and CRT between low, medium and high tertiles. Compared to the baseline, improved BCVA was observed, and CRT declined significantly after operation. Adverse events were most observed in high tertiles. A significant decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 was observed after 1 year.

Conclusions. The effectiveness of conbercept on neovascular AMD varies depending on the level of inflammation, which could be achieved by administering different injection frequencies at different levels of inflammation. Furthermore, conbercept is associated with the reduction of inflammatory factor (IL-6 and IL-8) levels after intravitreal injection, which suggests that suppressing inflammatory response might contribute to the clinical efficacy of anti-VEGF treatment. Our results provide a novel mechanism for conbercept in patients with neovascular AMD.

Key words: inflammation, age-related macular degeneration, hs-CRP, intravitreal injection, conbercept

Introduction

Elderly patients in developing countries commonly suffer from age-related macular degeneration (AMD), one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness.1 As a result of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), 10% of AMD cases can cause devastating vision loss.2 Studies have shown that numerous cytokine pathways are involved in CNV formation and leakage. Several treatments have been developed for CNV, including transpupillary thermotherapy, focal laser therapy, verteporfin ocular photodynamic therapy, intravitreal steroids, and surgical removal of the choroidal neovascular membranes.3 Nonetheless, adverse reactions and low cure rates persisted. However, advanced anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy has eliminated these problems completely.4 Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are the first-line treatment for neovascular AMD.5

Age-related macular degeneration is characterized by complement activation, inflammation, and choroidal endothelial cell loss. Additionally, researchers have suggested that C-reactive protein (CRP), a prototypical acute phase reactant, plays a role in AMD pathogenesis.6 Markers of inflammation, namely interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, have also been associated with AMD.7 Inflammatory ophthalmopathy can result in neovascularization, which is similar to the most debilitating form of neovascularization in AMD.8

The interaction between VEGF and inflammation in the clinical setting has not been extensively studied. Additionally, researchers do not know in what way the degree of inflammation affects the levels of VEGF and high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP). In this study, the clinical effect and safety of intravitreal injection of conbercept were evaluated in patients with neovascular AMD with different levels of inflammation.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine whether intravitreal injection of conbercept was effective and safe in patients with neovascular AMD with different levels of inflammation.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

We enrolled 120 consecutive patients diagnosed with neovascular AMD who underwent anti-VEGF therapy at the Fourth People’s Hospital of Shenyang (Shenyang, China) from September 2020 to January 2022. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients over 50 years old; 2) any type of fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) – diagnosing CNV induced by AMD under or near the fovea; and 3) treatment in accordance with the treatment plan. The following criteria were used for exclusion: 1) previous treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF or laser photocoagulation; 2) history of ophthalmic surgery except for cataracts; 3) CNV due to a reason other than AMD; 4) CNV with diseases of the retina such as diabetic retinopathy; 5) diseases that affect intravitreal injections in a severe manner; and 6) no clear indication of the severity of refractive effects of the stromal.

The study protocol adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University and the Institutional Review Board of Fourth People’s Hospital of Shenyang approved the study (approval No. KY2020-105). Each patient gave informed consent to participate in the study, and for their data to be collected and analyzed for research purposes.

Settings

Based on the hs-CRP levels, the patients were grouped into 3 tertiles: high, medium and low. The cut-off hs-CRP levels between the low, medium and high tertiles were 1.99 and 10.22 mg/L, respectively. All patients received the following tests: a measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure, color fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and a FFA (Figure 1). The BCVA was determined by using an international standard logarithmic visual acuity chart, and letter scores were collected from participants. Intraocular pressure measurements were performed using a tonometer without contact (Huvitz HNT-7000; Huvitz, Seoul, South Korea). Color fundus photography and the FFA were performed using a Topcon Fundus Camera (Topcon TRC-50X; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan). Spectral domain OCT products were used to perform the OCT test (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

Data collection

The patient’s eyeball was anesthetized, and the eyelid was opened. Next, the anterior chamber was punctured using a 0.45-mm needle, which was then inserted at the limbus and advanced to the middle of the anterior chamber. The eyeball was gently pressed to make approx. 0.1 mL of aqueous humor enter into a disposable syringe via the needle. The obtained aqueous humor samples were kept in a freezer at −76°C until analysis. The IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF levels were analyzed by performing an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at the Biochemistry Laboratory of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Measurement of cytokine levels

Inflammatory levels were determined by using a commercially available immunonephelometric kinetic assay (BN ProSpec; Siemens, Tarrytown, USA), and hs-CRP levels were determined using CardioPhase (Siemens). In this study, cytokine-specific ELISA kits were used to measure plasma and supernatant cytokine levels (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). A 0.025-mL sample of aqueous humor was used for each measurement. Absorbances were read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (ELx800; BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, USA). The assay ranges for VEGF, IL-6 and IL-8 were 15.6–1000, 2–250 and 2–300 pg/mL, respectively.

Drug treatment

As described previously, the same senior physician administered intravitreal injections of conbercept (0.5 mg/0.05 mL solution was obtained from Chengdu Kanghong Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) to all patients’ eyes.9 Three days before the injection, a dose of 5 μg (2 drops) of 0.5% levofloxacin was administered 4 times daily to the patient’s eye. A three-month course of intravitreal injections of conbercept was administered. The pro re nata (PRN) administration was retracted in the presence of any of the following changes: OCT scan revealing a persistent or recurrent intraretinal or subretinal fluid, new hemorrhage of the macula, new leakage or onset of classic CNV on FFA, a loss of vision greater than 1 line, or a decrease in conscious vision.9, 10 The eyes were bandaged with tobramycin–dexamethasone ointment after injecting conbercept into the conjunctival sacs. For 3 days after the surgery, eye drops were applied 4 times a day using 0.5% levofloxacin.

Follow-up

The patients were followed up for 12 months. Optical coherence tomography examinations and visual acuity tests were performed on a monthly basis. Every third monthly exam was conducted using FFA. The BCVA and central retinal thickness (CRT), as well as the leakage area of CNV were measured before and after the treatment in all patients. In addition, the adverse events (AEs) and cytokine markers (VEGF, IL-6 and IL-8) were recorded at admission and at 12-month follow-up. The trial was conducted according to the Technical Guidelines for Clinical Research of Drugs for Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (Center for Drug Evaluation, National Medical Products Administration, Beijing, China).

Statistical analyses

Mean value ± standard deviation was used for data with a normal distribution, and median (interquartile range) was used for data with a non-normal distribution. The Shapiro–Wilk test was utilized to check the normal distribution of data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to assess the differences between multiple sets of data. The Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to compare sets of non-normally distributed data. The Wilcoxon test for matched pairs was performed to test the differences between baseline and follow-up for each cytokine in all hs-CRP groups. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study utilized SPSS v. 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) for all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline data

A total of 120 consecutive patients suffering from neovascular AMD who underwent injection of intravitreal conbercept (3 + PRN) were included in the study. The participants were stratified based on the concentrations of hs-CRP in the intraocular fluid. As a result of pre-injection hs-CRP concentrations, patients’ inflammation levels were set as high, medium and low. The baseline demographic characteristics and ophthalmoscopic examination results of the 3 groups are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. There were no significant differences observed in the basic characteristics of the patients.

Visual acuity

As depicted in Figure 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, BCVA letter scores improved on average in all post-baseline assessments. The BCVA letter scores significantly improved between the 3 groups after 1 month of treatment (p < 0.001), which averaged increments of 5.92 ±1.19, 5.85 ±1.12 and 6.25 ±1.01, respectively. The improvements in BCVA continued up to 3 months and were maintained for 6 months, which averaged increments of 12.68 ±1.94, 11.20 ±1.95 and 10.10 ±1.13 at 3 months, respectively. There were no significant differences in BCVA letter scores between the 3 groups at 7, 10 and 12 months.

Central retinal thickness

Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4 summarize the characteristics of CRT at admission and follow-up across the 3 groups. There were no significant differences between the 3 groups at 1-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. However, there was a trend for CRT levels to decrease more rapidly in the group with a hs-CRP ≤ 2.

Choroidal neovascularization

In the group with a hs-CRP ≤ 2, FFA examinations at the last follow-up indicated that 24 eyes no longer had leakage areas within the CNV (60%), 14 eyes had reduced CNV (35%), and 2 eyes had enlarged CNV (5%). In the group with a hs-CRP > 2 but <10, 20 eyes no longer had leakage areas of CNV (50%), 14 eyes had reduced CNV (35%), and 6 eyes had enlarged CNV (15%). In the group with a hs-CRP ≥ 10, 16 eyes no longer had leakage areas of CNV (40%), 18 eyes had reduced CNV (45%), and 6 eyes had enlarged CNV (15%). In groups with low inflammation, conbercept had a better effect on leakage areas of CNV compared to groups with high inflammation, but no significant difference was observed.

Cytokine

Conbercept injections significantly reduced levels of VEGF and proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 at low- and medium levels of inflammation (Table 3). Compared to medium- and high levels of inflammation, conbercept had a significantly higher anti-VEGF and inflammatory effect at low inflammation levels (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Clinical outcomes and ocular adverse events at 12-month follow-up

The number of conbercept injections on average between the 3 groups was 5.93 (5.55–6.30), 5.85 (5.49–6.21) and 6.25 (5.93–6.57) in the low, medium and high inflammation groups, respectively. There was a trend for a greater number of injections in the high inflammation group (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 6). Ocular AEs were summarized in Table 4. An intravitreal injection did not result in serious complications, such as porogen detachment or endophthalmitis, during the 12-month follow-up period. Increased intraocular pressure, pain in the eye and conjunctival hemorrhage were ocular AEs. In the low-tertile group, cumulative AEs were significantly lower than in the medium- and high-tertile groups.

Discussion

To date, the efficacy of conbercept in treating neovascular AMD at different levels of inflammation and anti-inflammatory effects of anti-VEGF agents are still unclear. Approximately 8% of the world population suffers from AMD, a progressive neurodegenerative disease.11 Developed countries have the highest rate of elderly blindness caused by AMD. Neovascular growth of patients suffering from neovascular AMD, featuring CNV, should be driven by a complex process that involves VEGF-A, a signal protein.12 The development of AMD is closely associated with neovascularization and abnormal vessel permeability in the eye, mediated by VEGF.13 In recent years, conbercept has become a leading anti-VEGF drug.14 A major benefit of conbercept is that it inhibits retinal angiogenesis and reduces vascular permeability.15 Additionally, inflammation leading to VEGF-A expression also contributes to AMD pathology.16

Regulatory factors associated with AMD, including smoking, dietary factors, obesity, and lipid levels,17, 18, 19 which are also related to cardiovascular disease (CVD), have become better understood in the past decade. Despite the fact that CVD and AMD have common risk factors, the evaluation of the potential relationship between CVD-related biomarkers and AMD is strongly advised.8 As a physiological marker of systemic inflammation, hs-CRP is associated with advanced AMD, which is also consistently associated with CVD. Although there may be new detection methods of other inflammatory markers in the future, with better accuracy, standardization, and characteristics other than those observed in the current detection methods, present clinical practice utilizes hs-CRP detection as a useful marker.20 In our study, conbercept showed a greater reduction in inflammation (IL-6 and IL-8) at lower levels of hs-CRP and a much more stable anti-VEGF effect. Conbercept is a large protein molecule and is known as the extracellular domains of VEGF receptors 1 and 2, which were combined with the human immunoglobulin Fc region to construct a new bait receptor protein.15 In addition, conbercept binds to placental growth factor (PIGF), VEGF-B and VEGF-A, which regulate inflammation.21, 22 Meanwhile, by increasing the number of injections, conbercept is expected to provide a similar clinical effect in patients with high levels of hs-CRP.

In our study, intravitreal injections of conbercept rapidly improved eyesight in neovascular AMD patients. After receiving 3 scheduled conbercept injections, improvements were observed, and these improvements were sustained over a 12-month variable dosing regimen. This study found that conbercept was well tolerated without systemic serious adverse events (SAEs). The intravitreal injections were associated with a high rate of AEs, including conjunctival hemorrhages and increased intraocular pressure. Due to the high molecular weight (143 kDa) of conbercept, systemic AEs are reduced, and the drug’s activity is prolonged, limiting its permeability through the blood–eye barrier, with less systemic exposure than systemic medication.23

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First of all, only a small number of patients participated in the study. Secondly, referral bias may have been present since the study was conducted in a single hospital setting. Also, there was no long-term data or follow-ups, which will be addressed in a future study. Finally, the small sample size of our study prevented us from detecting any AEs related to the drug. Continuous monitoring of short-term effects will be carried out during the post-marketing phase.

Conclusions

The effectiveness of conbercept on neovascular AMD varies depending on the level of inflammation, which could be achieved by administering different injection frequencies at different levels of inflammation. Furthermore, conbercept is related to reduced inflammation (IL-6 and IL-8) at follow-up after intravitreal injections, indicating an anti-inflammatory function for conbercept as anti-VEGF treatment, which could provide another explanation for conbercept treatment in neovascular AMD patients.

Availability of data and materials

The authors of the study are willing to make the raw data supporting their conclusions readily accessible.

Supplementary data

The Supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8330239. The package contains the following files:

Supplementary Table 1. One-way ANOVA test for basic characteristics with post-hoc results.

Supplementary Table 2. Changes of BCVA letter scores in all post-baseline assessments.

Supplementary Table 3. One-way ANOVA test for BCVA letter scores with post-hoc results.

Supplementary Table 4. One way ANOVA test for central retinal thickness outcome with post-hoc results.

Supplementary Table 5. One-way ANOVA test for cytokine levels with post-hoc results.

Supplementary Table 6. One-way ANOVA test for clinical outcomes with post-hoc results.