Abstract

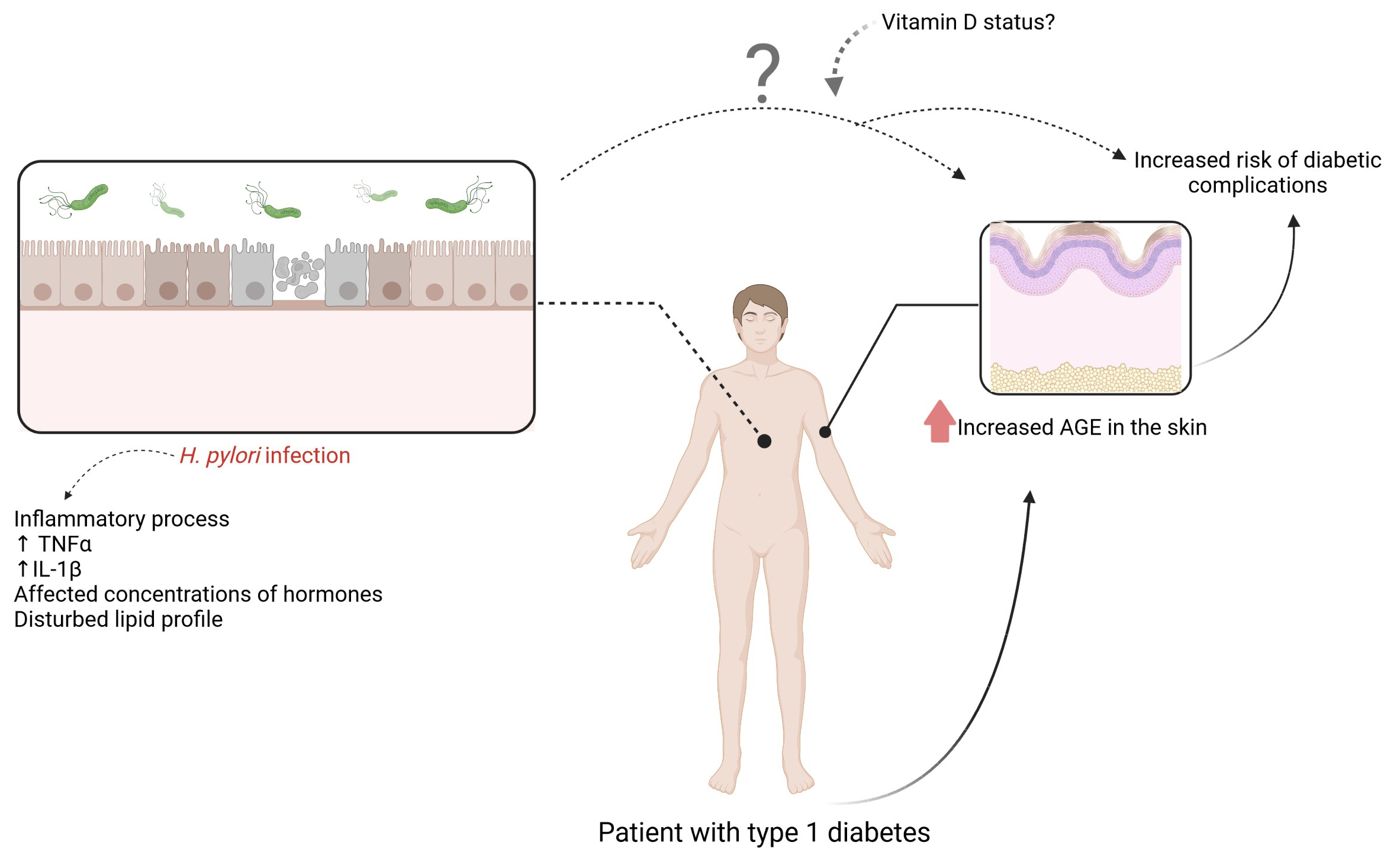

Background. Helicobacter pylori infection (HPI) is more frequently diagnosed in patients with diabetes. Insulin resistance in patients with type 1 diabetes (DMT1) is associated with the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the skin and progression of chronic complications.

Objectives. Assessment of the relationship between the incidence of HPI and skin AGEs in patients with DMT1.

Materials and methods. The study included 103 Caucasian patients with a DMT1 duration >5 years. A fast qualitative test was performed to detect the HP antigen in fecal samples (Hedrex). The content of AGEs in the skin was estimated using an AGE Reader device (DiagnOptics).

Results. The HP-positive (n = 31) and HP-negative (n = 72) groups did not differ in terms of age, gender, duration of diabetes, fat content, body mass index (BMI) and lipid profile, metabolic control, and inflammatory response markers. The studied groups differed in the amount of AGEs in the skin. The relationship between HPI and increased AGEs in the skin was confirmed in a multifactor regression model taking into account age, gender, DMT1 duration, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), BMI, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and the presence of hypertension, and tobacco use. The studied groups also differed in serum levels of vitamin D.

Conclusions. Increased accumulation of AGEs in the skin of patients with DMT1 with coexisting HPI suggests that eradication of HP may significantly improve DMT1 outcomes.

Key words: vitamin D, H. pylori, advanced glycation end products, type 1 diabetes, diabetic complications

Background

In recent years, a significant increase in the incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection (HPI) has been observed.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 30% of the population in developed countries and 70% of the population in developing countries carry this Gram-negative anaerobic bacilli.2 Helicobacter pylori (HP) is the principal etiological agent of diseases such as gastritis, peptic ulcers and gastric cancer.3 The infection may aggravate gastric symptoms of patients treated with chronic steroid therapy or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and plays an important role in the exacerbation of certain autoimmune diseases, such as hypothyroidism. Furthermore, chronic inflammation associated with infection and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines may cause many extragastric symptoms such as iron deficiency anemia, insulin resistance, ischemic heart disease, and neurological disorders. Meta-analysis data from 2013 confirm that HPI is recognized significantly more often in patients with diabetes, and patients infected with HP are more frequently diagnosed with diabetes.4 The relationship between the infection and insulin resistance of peripheral tissues is yet to be determined.

Type 2 diabetes (DMT2) patients infected with HP showed significantly increased Homa Insulin Resistance Index (HOMA-IR) values than those without any coexisting infection. Similar observations have been made in patients with type 1 diabetes (DMT1).5 Insulin resistance in DMT1 patients is associated with thickening of the intima-media complex (IMT), accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the skin, and development of chronic complications. The assessment of the association of HPI with anthropometric parameters and insulin resistance indices may bring significant clinical benefits. Enhanced accumulation of AGEs in the skin and, thus, an increased risk of chronic complications of diabetes in patients with coexisting HPI, may suggest that eradication of the bacteria might alleviate some of the complications of DMT1.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between the presence of HPI and the accumulation of AGEs in the skin of patients with DMT1.

Materials and methods

The study involved 103 patients with DMT1 treated in the Department of Gastroenterology, Dietetics, and Internal Diseases and in the Department of Internal Medicine and Diabetology (Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland) in 2017–2020, who met the criteria for inclusion. All patients gave informed consent.

The inclusion criteria were:

1. DMT1 (diagnosis supported by the presence of autoantibodies ICA, IA2 and GAD) treated with intensive functional insulin therapy or multiple injections of fixed insulin doses;

2. Age > 18 years;

3. Caucasian;

4. Diabetes duration > 5 years;

5. Informed consent for study participation.

Exclusion criteria were:

1. Diabetes other than DMT1;

2. Persons treated with chronic proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers and bismuth preparations;

3. Subjects receiving antibiotics within 1 month before study entry;

4. Persons treated with chronic steroids, NSAIDs;

5. Pregnancy;

6. Other chronic gastrointestinal diseases (gastric cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.).

Ethics committee

The study protocol was approved by the Poznan University of Medical Sciences Bioethics Commission (approval No. 504/16 granted on May 5, 2016). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a prior approval by the institution’s human research committee. All patients gave written informed consent.

Evaluation of Heliobacter pylori infection

A noninvasive method was used to assess the presence of HP in patients. A rapid, qualitative, one-step test for the detection of the HP antigen in stool samples was performed (Helicobacter Antigen Test; Hydrex Diagnostics, Warszawa, Poland) (Ref HXHPAg10, Ag20, Ag25). The principle of the test is based on the immunochromatographic method (monoclonal antibodies directed against HP on the test strip). The mean sensitivity and specificity of the test is 94.5%. The presence of the HP antigen in feces is confirmed by the formation of a colloidal gold antibody complex of HP antigen–antibody conjugate.

Anthropometric parameters

and survey data

Anthropometric indicators (height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), waist and hip circumference (WHR index)) were analyzed. The daily dose of insulin was evaluated. The estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR) was calculated using published formulae.6 The visceral adiposity index (VAI) was evaluated based on a previously published gender-specific formula.7

Total body fat was assessed with electrical bioimpedance using a Tanita BC-418 MA (Tanita Polska, Poznań, Poland) analyzer. As a result of those measurements, abdominal visceral body fat (AViscBF) content was presented on a scale from 1% to 59% (resolution: 0.5%) and percentile content of trunk body fat on a 5–75% scale (resolution: 0.1%). The device is CE certified and complies with European Union Directive MDD93/42EEC for medical appliances. Total body fat and visceral adipose tissue were estimated using electrical bioimpedance according to the WHO age- and gender-adjusted criteria.8 The clinical presentation of the investigated group is shown in Table 1.

Evaluation of chronic complications

The presence and severity of chronic complications were evaluated. Retinopathy was diagnosed when at least 1 microaneurysm was found in both eyes and was classified according to the recommendations of the Polish Diabetes Association. Diabetic kidney disease was recognized by the assessment of renal function (creatinine serum concentration, calculation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) following the pattern of Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD; the assessment of excretion of albumin in the urine)). Diabetic kidney disease was defined as albuminuria or evident proteinuria. Albuminuria was defined according to the recommendations of the Polish Diabetes Association.9 Peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed based on 2 out of 5 abnormal parameters such as the sensation of touch, vibration, temperature, pain, or knee or ankle reflex removal. Touch sensation was assessed using Semmes–Weinstein 10 g pressure monofilament (Medische Vakhandel, Veendam, the Netherlands), vibration sensation was assessed with Tunning Fork C 128 Hz/C 64 Hz according to Ryder–Seiffer function diagnostics 2 (Suzhou Yongtaite Dianzikejiyouxiangongsi, Suzhou, China), temperature sensation was evaluated with a metal and plastic tip roller (Tiptherm; GIMA Italy, Gessate, Italy), and by examining the ankle jerk reflex. Autonomous neuropathy was diagnosed based on heart rate variability test (rest assessment, respiratory test, Valsalva test, orthostatic test) with the use of ProSciCard III® apparatus (2010; CPS GmbH, Rohrdorf, Germany).

Quantitative assessment

of skin autofluorescence

The content of AGEs was evaluated using the AGE Reader device (type 214D00102; DiagnOptics, Groningen, the Netherlands). The device emitted ultraviolet light with a wavelength of 300–420 nm and was used to illuminate 1 cm2 of skin on the inner forearm, about 10 cm away from the elbow joint. A built-in spectrometer registered light in the range of 300–600 nm (autofluorescence (AF)). The AF score was calculated automatically (the ratio of the amount of light emitted by the skin to the amount of light emitted by the device).

Advanced products of protein glycation can be assessed in serum; however, due to their high heterogeneity and instability, as well as physiological fluctuations in their concentrations, this test is not particularly reproducible.10 Moreover, the cost of serum AGE determination is high. Skin autofluorescence (SAF) is a simple and noninvasive technique that has been validated based on the gold standard, the assessment of AGE in skin biopsy.11 The SAF directly correlates with both fluorescent (pentosidine) and nonfluorescent (Nε-carboxymethyllysine (CML) and Nεcarboxy-ethyllysine (CEL)) advanced glycation products in skin biopsy.12 In a study by Koetsier et al., SAF reference values were established for healthy Caucasians.13 The SAF increased linearly with age at approx. 0.023 units (AU) per year for those aged up to 70 years. Tobacco smoking was associated with an absolute increase in SAF of 0.16 AU, and in this case, age was not additive. Gender had no effect on SAF in non-smokers, while in the smoking group, women had 0.2 AU higher skin AF than men, with no further age-related increase.

Laboratory tests

Basic laboratory parameters were also evaluated: the value of glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured with turbidimetric and immunoinhibition methods using the cobas® 6000 device (norm: 4.8%–6.5%; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland); lipid metabolism parameters (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) fractions, and triglycerides concentration in serum) using the enzymatic method and C-reactive protein (CRP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and creatinine using standard methods. The calculation of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was based on MDRD study equation (norm: 90–120 mL/min/1.73 m2). The concentration of vitamin 25(OH)D3 was determined with radioimmunoassay.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica PL v. 13.3 (StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o., Kraków, Poland), MedCalc v. 20.115 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) and R software v. 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The compliance of the interval data distribution with the normal distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normal distribution was not observed in most of the data. In the analysis, a statistical method for nonparametric variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. The results are presented as numbers and percentages, as well as medians and interquartile range (IQR). The Fisher’s test was applied to analyze the categorical data. In order to assess the influence of HPI on the onset of long-term complications of the disease, the logistic regression model with no automatic predictor selection was applied. Observations complied with the model’s assumptions: 1) no extreme outliers (>3 IQR), after removing 2 such values; and 2) no multicollinearity among explanatory variables (variance inflation factor (VIF) of 0.1 for each of the numerical predictors). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the study group, 30% of patients were found positive for HPI. The HP-positive and HP-negative groups did not differ in age, sex, duration of diabetes, metabolic control, and inflammatory response markers, as well as regarding fat content, BMI and lipid profile. The studied groups varied in the amount of AGEs in the skin (Table 2), and in the levels of vitamin D. Vitamin D serum concentrations were significantly higher in patients without HPI. However, no differences in fat content, BMI and lipid profile were noted. Differences between HP-positive and HP-negative groups are shown in Table 2. In the logistic regression analysis, lower vitamin D levels were associated with the presence of HPI (odds ratio (OR): 0.89; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.81–0.96, p = 0.005), and the higher SAF was associated with the presence of HP (OR: 5.43; 95% CI: 1.88–18.55, p = 0.003). Age, gender, smoking status, BMI, arterial hypertension, HbA1c value, and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration were not related to the presence of HPI (Table 3).

Discussion

It has been previously demonstrated that an increased prevalence of HPI occurs in patients with autoimmune diseases, such as hypothyroidism and DMT1. The co-occurrence of HP and DMT1 is also associated with a higher level of islet cell antibodies (ICA). The intensification of the autoaggression process is associated with worse diabetes control and increases the risk of chronic complications, such as retinopathy and neurological disorders.9

The results of studies evaluating the influence of HPI on metabolic control and its relation to the occurrence of chronic complications in diabetic patients are inconclusive.14, 15 The meta-analysis by Dai et al. found significantly higher glycated hemoglobin values in patients with DMT1 and HPI.15 However, this relationship was not confirmed in patients with DMT2. A study by Demir et al. showed that HPI was associated with the development of neuropathy. However, no such relationship was found when analyzing glycemic control, occurrence of retinopathy or diabetic kidney disease.16 Moreover, patients with DMT1 may show higher levels of HP colonization because of delayed gastric emptying and the occurrence of gastroparesis, as the result of autonomic neuropathy.17 Chung et al. demonstrated that the incidence of microalbuminuria was significantly higher in patients with DMT2 and coexisting HPI.18 Similarly, in a study by Zizzi et al., it was found that HPI is associated with a higher incidence of proteinuria in patients with DMT2.19 The relationship between HPI and diabetic nephropathy has been shown in a study by Bajaj et al.20 The HPI also aggravates the symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis.21 The association between HPI and retinopathy has also been demonstrated in the study by Agrawal et al.22 However, in our study group, no statistically significant differences in disease complications were observed in patients with and without HPI (Mann–Whitney test, p > 0.05). This may be due to the relatively small number of individuals presenting with complications in the study group (24.7% on average) and the short or completely unknown duration of HPI. Indeed, a prolonged inflammatory process enhances the development of chronic complications. The HPI causes a local inflammatory process that may not reflect a long-term systemic response. However, chronic inflammation is a well-known risk factor for diabetic chronic complications. The HPI could cause a long-lasting, low-intensity inflammation that affects cell metabolism. In the study by Noach et al. that used a multivariable logistic regression model, HPI was not associated with elevated CRP levels. However, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β levels were significantly higher in HP-positive patients. This may be of particular importance in patients with newly diagnosed DMT1 enrolled into this study, who present with higher numbers of IL-1β-expressing monocytes and a reduced number of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) expressing IL-6, when compared to nondiabetic individuals.23 There were no elevated inflammatory response markers in the study group, but the value of CRP was higher in the HP-positive group. However, this difference was not statistically significant. In addition, elevated IL-1 levels may contribute to increased insulin resistance and play a central role in driving tissue inflammation during metabolic stress in patients diagnosed with diabetes.24

The phenomenon of insulin resistance is associated not only with DMT2. A growing body of evidence shows that insulin resistance may play an important role in the development of complications in DMT1. Reduced sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin limits the possibility of achieving good metabolic control of carbohydrate, lipid and blood pressure. An increase in insulin resistance due to HPI is another factor that may affect the control of disease progression in diabetes.25, 26 Local gastritis, induced by the bacterium, can also affect the concentration of hormones such as gastrin and somatostatin, as well as leptin and ghrelin, which are important factors regulating the content and hormonal function of adipose tissue in the body.27, 28 In the present study, no differences were observed in insulin-resistant markers (VAI, eGDR) between both groups of patients (HP-positive and HP-negative). The HPI may also influence lipid profiles. A significant increase in LDL-C and a decrease in HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations were observed in patients without diabetes and in patients with DMT2.29, 30 However, no studies evaluating these parameters in patients with DMT1 and concomitant HPI have been published. No such connection was found in the group of patients studied by our team.

In a study by Meerwaldt et al., in diabetic patients, 70% of SAF was above 95% CI of the mean value in the control group.12 In diabetic patients, SAF directly correlated with age, duration of diabetes and the value of HbA1c.12, 31 Samborski et al. indicate that SAF was significantly higher in DMT1 patients than in the controls without diabetes.32 Moreover, there was a significant positive association between SAF and the age of patients. A significant positive relationship was found in diabetic subjects between SAF, the duration of diabetes and HbA1c. The SAF measurement reflects glycemic control over a longer period than that reflected by HbA1c levels.33 It has also been demonstrated that SAF is a better predictor of the development of chronic complications and mortality from diabetes over time (5–10 years) than HbA1c.34, 35, 36 Moreover, AGE values (>2.0 AU for over 5 years) are a significant marker of the development of vascular complications of micro- and macroangiopathy. An increase in SAF value is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death.36

Our results indicate that HPI is associated with AGEs in patients with DMT1. This is the first study assessing the relationship between HPI and the presence of AGEs in the skin using AF. In previous studies, the local receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) concentrations in gastric epithelial cells was assessed. It has been found that RAGE expression increased in HP-infected cells compared to uninfected cells.37

The HP produces many virulence factors such as vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), which induces programmed cell necrosis, causes HMGB1 release and enhances the pro-inflammatory response.38 However, the mechanisms of the activation of HMGB1 expression and RAGE by HPI to promote inflammation in gastric epithelial cells are not fully understood.39

Furthermore, a high rate of positive RAGE expression was observed in the gastric biopsies.

In addition, a significantly higher percentage of RAGE expression is found in biopsies with dysplasia or carcinoma in situ.40 Many studies show an association between HPI and metabolic syndrome, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and gastric and lower gastrointestinal oncogenesis.41

The role of RAGE in the process of HP adhesion to the epithelial cells of the stomach is also worth emphasizing and confirms the belief that HP is undoubtedly related to the content of final products of protein glycosylation in the body. In the study by Rojas et al., the role of the receptor for RAGE on the adhesion of HP to gastric epithelial cells was defined. Bacilli of HP bind with immobilized RAGE. It means that RAGE represents a new factor in the pathogenesis of HPI.42 There is no evidence in the literature showing that the eradication of HP reduces AGEs; this would be an important follow-up study.

The significantly lower vitamin D levels in HP-positive patients are also important. As shown in our study, patients with lower vitamin D levels and DMT1 are more likely to be HP-positive. Vitamin D deficiency can have a negative impact on metabolic status and glycemic control in DMT1, although the supplementation of vitamin D improves these outcomes.43 On the other hand, low vitamin D levels are associated with an increased risk of HPI.44 Moreover, many data show that vitamin D deficiency may result in failure to eradicate HPI on treatment.44, 45 In a study performed by Yildirim et al., out of 220 patients with HPI, 22.7% were found to be unresponsive to eradication treatment. In the group where eradication failed, mean vitamin D levels were significantly lower when compared to the successful treatment group.45 El Shahawy et al. demonstrated a negative influence of vitamin D deficiency on the results of eradication therapy.46 Finally, a recent meta-analysis confirmed these findings and additionally showed that 25-OH vitamin D supplementation improved eradication outcomes.47

Population studies show that the efficacy of HPI eradication in patients with DMT2 is also lower than in those without diabetes. In patients with DMT1, the infection is at risk of recurrence.48 This is an important observation since, in studies carried out in patients with DMT2, a statistically significant improvement in the metabolic control of diabetes was observed after effective treatment of the infection.49

Considering all the data mentioned above and the results of our study, we strongly believe that HPI eradication should be implemented as a potential adjunct therapy, maximizing the effectiveness of classical treatment of DMT1 in HP-infected patients. This is still a matter of debate whether vitamin D should be routinely included in therapeutic protocols in HPI. Appropriate clinical trials should help us to answer this question in the near future. Nevertheless, a growing body of evidence suggests that DMT1 patients would especially benefit from supplementation of vitamin D during and after treatment for HPI.

Limitations

The limitations of the study were a relatively small research group, lack of control group and restrictions related to the AGE measurement technique in the skin with the AGE Reader device.

Conclusions

An increased accumulation of AGEs in the skin of patients with DMT1 with coexisting HPI may be a reason to consider eradication therapy in this group of patients.

In the group of DMT1 patients, lower vitamin D levels were observed and associated with HPI.

Further studies on larger groups of DMT1 patients should be considered to assess the connection between AGE and HPI. Further studies are also necessary to indicate whether HP eradication reduced the accumulation of protein glycation end products in the skin.