Abstract

Introduction. According to many reports, multidisciplinary comprehensive care alleviates Parkinson’s disease (PD) more frequently than any other standard care, though the results were found to vary greatly.

Materials and methods. A systematic literature search up to July 2022 was performed and 1234 related studies were evaluated. The chosen studies comprised 1115 subjects with PD who participated in baseline trials; 633 of them were under multidisciplinary comprehensive care, while 482 were under standard care. Odds ratios (ORs) and mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to measure the results of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD by the contentious and dichotomous approaches with a random or fixed influence model employed.

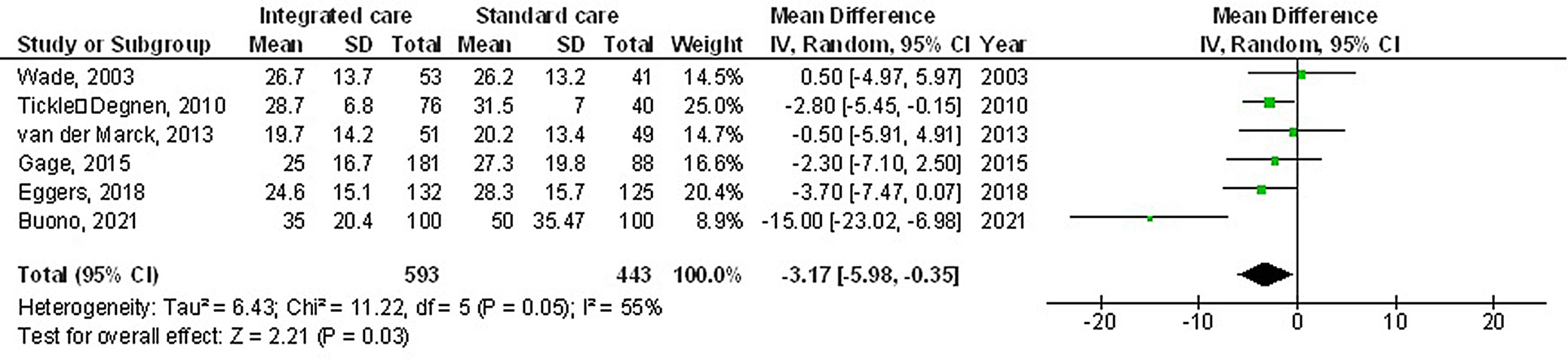

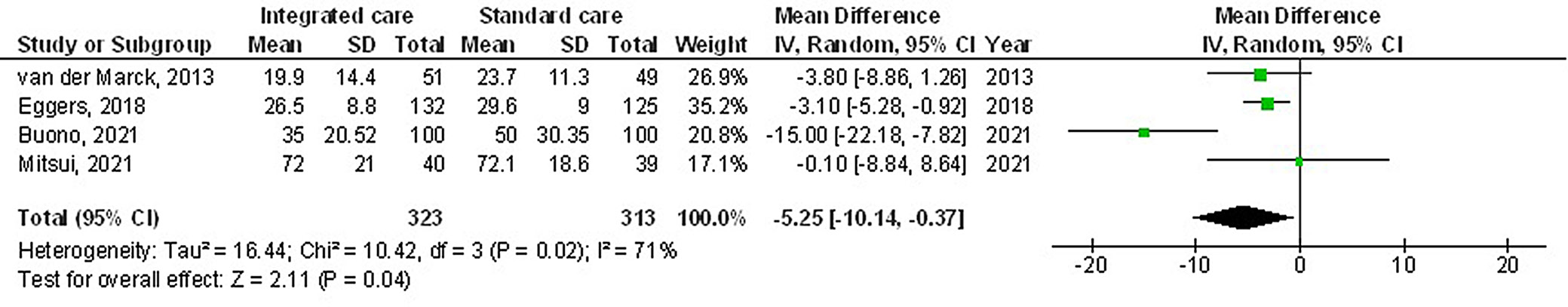

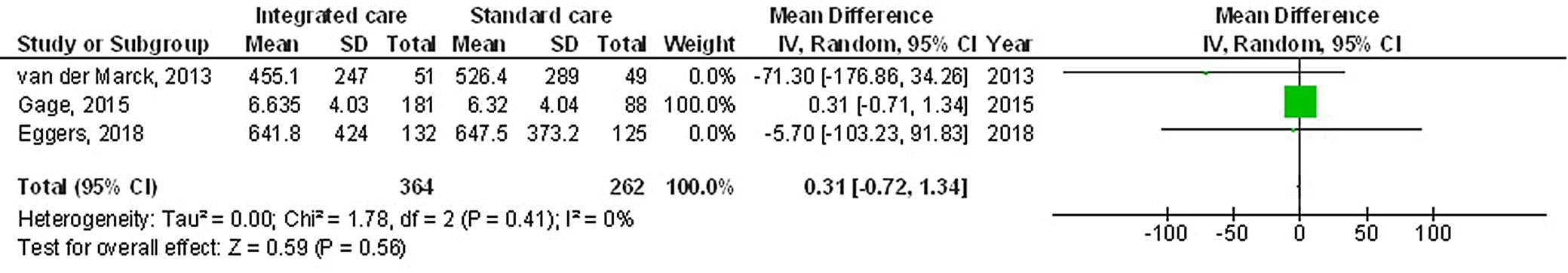

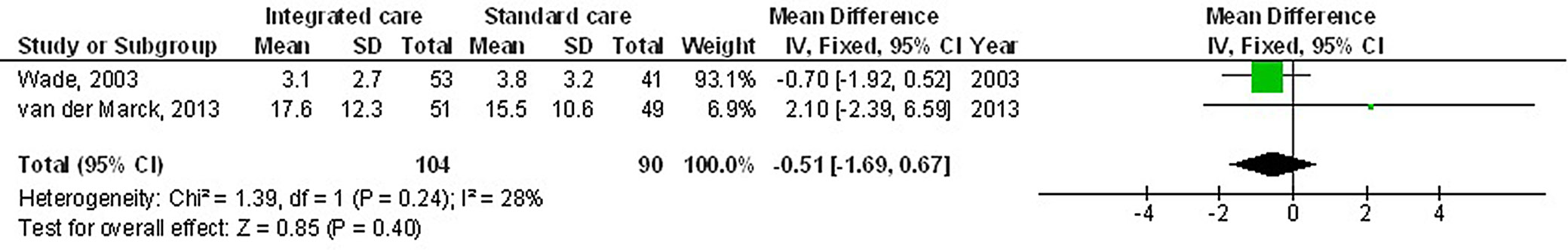

Results. The use of multidisciplinary comprehensive care resulted in significantly better health-related quality of life (HRQL) (MD: −3.17; 95% CI: −5.98–−0.35, p = 0.03) and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) score (MD: −5.25; 95% CI: −10.14–−0.37, p = 0.04) compared to the standard care for subjects with PD. Nevertheless, no significant difference was found between multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care for subjects with PD regarding medication dosage (MD: 0.31; 95% CI: −0.72–1.34, p = 0.56) and caregiver strain (MD: −0.51; 95% CI: −1.69–0.67, p = 0.40).

Conclusions. Outpatient multidisciplinary comprehensive care models may improve patient-reported HRQL and UPDRS score; nevertheless, no significant difference was found in terms of medication dosage and caregiver strain compared to the standard care for subjects with PD. The small sample size of 2 out of 7 analyzed studies and the small number of studies in certain comparisons requires attention when analyzing the results.

Key words: Parkinson’s disease, integrated care, health-related quality of life, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurological condition with bradykinesia, tremor, stiffness, and postural instability as its hallmarks. These clinical symptoms can be present in several illnesses, and the clinical syndrome is known as parkinsonism. Parkinsonian disorders are conditions where parkinsonism is a dominant feature. Parkinson’s disease has toxic, traumatic and degenerative vascular etiologies.1 In autopsy series, synucleinopathies (Lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy) and tauopathies (progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration) are the most prevalent neurological causes of PD.2 Because the above causes include additional symptoms, some of these are regarded as atypical PD.3, 4 Parkinson’s disease is characterized by irregularities of movement, including tremors, gait and balance issues, and slowness of movement.5 The abnormalities of neuronal and muscular activity that are associated with these symptoms are well understood.6 Motor symptoms can also be described in terms of motor control, a level of description that explains how movement variables, such as a limb’s position and speed, are controlled and coordinated.7 Understanding motor symptoms as motor control abnormalities means identifying how the disease disrupts normal control processes.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In the case of PD, movement slowness, for example, would be explained by a disruption of the control processes that determine normal movement speed.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The capacity to manage behaviors can be impacted by emotions.24 The valence of emotional cues may have a varied impact on certain motor skills; however, it is unclear whether emotions have a positive or negative impact on action control.25 The stop-signal task, which calculates the ability to completely cancel a response to the presentation of a stop signal using the stop signal reaction times, is a method for measuring reactive inhibitory control.26 When challenged with emotional stimuli, such as stop signals in stop-signal tasks, action control is both impaired and assisted, with conflicting outcomes for positive compared to negative stimuli.27

Since the beginning of cognitive neuroscience, it has been known that emotions have an impact on several executive functions, including the inhibition of action; however, the intricate interplay between emotional stimuli and action regulation is still not fully comprehended.28 The stop-signal task is a method of assessing inhibitory control.29 Regarding internal emotional stimuli such as stop signals in stop-signal tasks, it has been discovered that action control is both aided and impaired.30

Currently, the most effective medical care available for patients with PD entails a medical professional applying cutting-edge diagnostic and therapeutic knowledge acquired from cohort studies and clinical trials.31 The ability, experience and intuition of medical professionals to translate knowledge based on collective decision-making to individual decision-making is crucial to the much-needed customization of medicine.32 Within 20 years, such individual therapeutic decisions will be substantially backed by digital technologies, creating a new healthcare ecosystem that is frequently referred to as “digital medicine.”33 New “digital health pathways” or data-driven personalized decision support, which is based on a combination of multimodal data sources, including evidence-based medical knowledge, is anticipated to be part of the next phase of digitalization (e.g., clinical guidelines).34 Currently, PD can only be treated with symptomatic medications.35 Both motor and a wide range of nonmotor symptoms in PD contribute to the general disease problem.36 This complexity calls for a personalized, all-encompassing therapeutic strategy. Given the variety of symptoms of the disease, PD nurses or care coordinators who specialize in the condition can support patients in achieving their unique therapeutic objectives.37 Better self-management information, adequate interdisciplinary collaboration amongst various healthcare professionals, appropriate amount of time to discuss potential future scenarios, and a specific healthcare professional guiding and support are among the reported core needs from the patient’s point of view.38 With widely differing degrees and intensities, several distinct multidisciplinary comprehensive care models have been formed globally to meet these needs.39 All of these models strive to provide PD patients with structured, individually tailored treatment programs. Until now, programs’ venues, team makeup or degree of clinical integration have not been consistent. The majority of programs do, nevertheless, adhere to some common disciplines. Additionally, the outcomes of published data vary in terms of study design and findings (including improvement in HRQL). The nomenclature employed is also not uniform, with care models most frequently being referred to as “multidisciplinary”, “interprofessional”, “interdisciplinary”, or “integrated”. The phrase “multidisciplinary comprehensive care” is consistently used. The delivery of multidisciplinary comprehensive care involves at least 1 patient and numerous healthcare workers from various specialties. The accessible data and evidence on present multidisciplinary comprehensive care models and their results concerning the improvements in the HRQL of PD patients are synthesized in the current meta-analysis and systematic review, along with Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), medication dosage and caregiver strain. The most often used rating tool for PD is the UPDRS.40, 41 Three subscales, namely (I) Mentation, Behavior, and Mood; (II) Activities of Daily Living; and (III) Motor Examination, make up the total UPDRS score, which consists of 31 items.40 Although this information might provide help in clinical decision-making, the UPDRS does not evaluate general cardiovascular fitness and offers only scant details on functional performance relevant to daily activities. Therefore, it is important to assess the UPDRS’s ability to predict outcomes for time- and resource-intensive tests, such as ambulatory function.

Objectives

The objective of the study was to determine the outcomes of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD, e.g., HRQL, UPDRS, medication dosage, and caregiver strain.

Materials and methods

Information sources

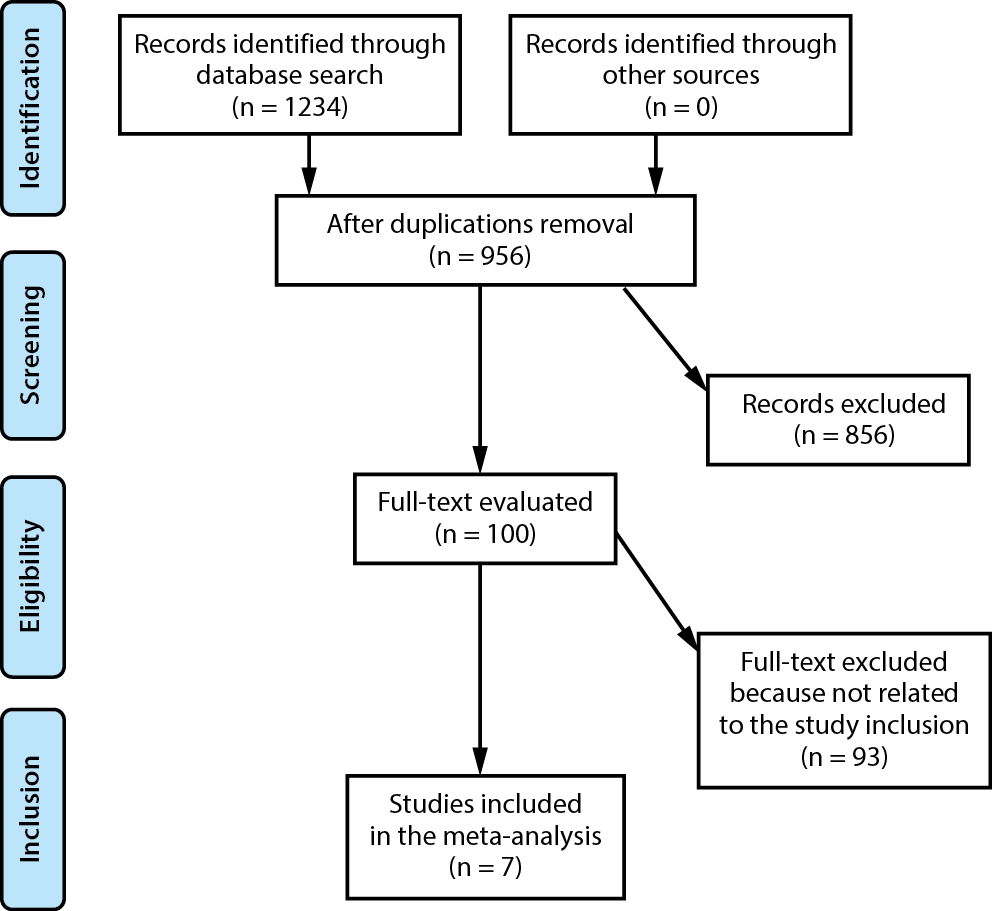

All studies included in the analysis involved humans as research participants. Language or study scope were not among the inclusion or exclusion criteria. The list of publications did not include commentaries, review papers and papers that did not present any relationship between the studied phenomenons. The complete course of the study is shown in Figure 1. The studies were chosen for the meta-analysis when the following inclusion criteria were met:

1. The study was either a controlled trial, observational, prospective, or retrospective study.

2. The selected subjects were subjects with PD.

3. The intervention program included multidisciplinary comprehensive care.

4. The study was the consequence of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD.

The studies which did not present any comparison of outcomes within its protocol, studies that did not examine multidisciplinary comprehensive care in subjects with PD, and research papers on subjects with no PD or without multidisciplinary comprehensive care were excluded from the study.

Search strategy

A protocol regarding search strategy was developed following the PICOS concept, and was characterized as follows: population (P) – subjects with PD; intervention (I) – multidisciplinary comprehensive care technique; comparison (C) – multidisciplinary comprehensive care compared to standard care; outcomes (O) – HRQL, UPDRS, medication dosages, and caregiver strain; study design (S) – no restrictions.42, 43

A thorough search of the OVID, Embase, Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases up to June 2022 was conducted, using an arrangement of key words and correlated terms regarding multidisciplinary comprehensive care, HRQL, PD, and UPDRS (as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1). To single out studies that did not examine the relationship between multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care in subjects with PD, all included papers were listed in an EndNote file, duplicates were eliminated, and the titles and abstracts were assessed.

Data collection process

The data collected for the purpose of the study included the last name of the first author, country, quantitative and qualitative assessment technique, the information source, the results of the assessment, and statistical analysis results.44

Study risk of bias assessment

Two authors individually evaluated the methodology of the 7 chosen papers to ascertain the possibility of bias in each study. The procedural quality was assessed using the “risk of bias instrument” from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions v. 5.1.0.45 Each study was assessed according to the evaluation criteria and assigned one of 3 levels of bias risk. A study was rated as having a low risk of bias if all the quality standards were met. If one or more requirements were not met, a study was rated as having a moderate risk of bias. High risk of bias occurred if one or more quality criteria were not met at all or were only partially met. The original article was revised to remove any inconsistencies.

Effect measures

Only the studies that reported and assessed the influence of multidisciplinary comprehensive care in comparison to standard care underwent sensitivity assessment. Sensitivity and subclass analyses were utilized to compare the consequences of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD.

Statistical analyses

The current meta-analysis used a fixed- or random-effects model with dichotomous and continuous techniques to compute the odds ratio (OR) and mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The heterogeneity (I2) index was calculated using a range of 0–100%. The values were around 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively, and showed no, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity.46 Additional characteristics that show a high degree of similarity between the included studies were analyzed to confirm the employment of the correct model. The random-effects model was considered if I2 was 50% or above; if I2 was less than 50%, the likelihood of employing the fixed-effects model increased.46 By stratifying the initial evaluation according to the previously mentioned outcome categories, the subclass analysis was finished. The value of p = 0.05 indicated statistical significance for differences between the subcategories.

Reporting bias assessment

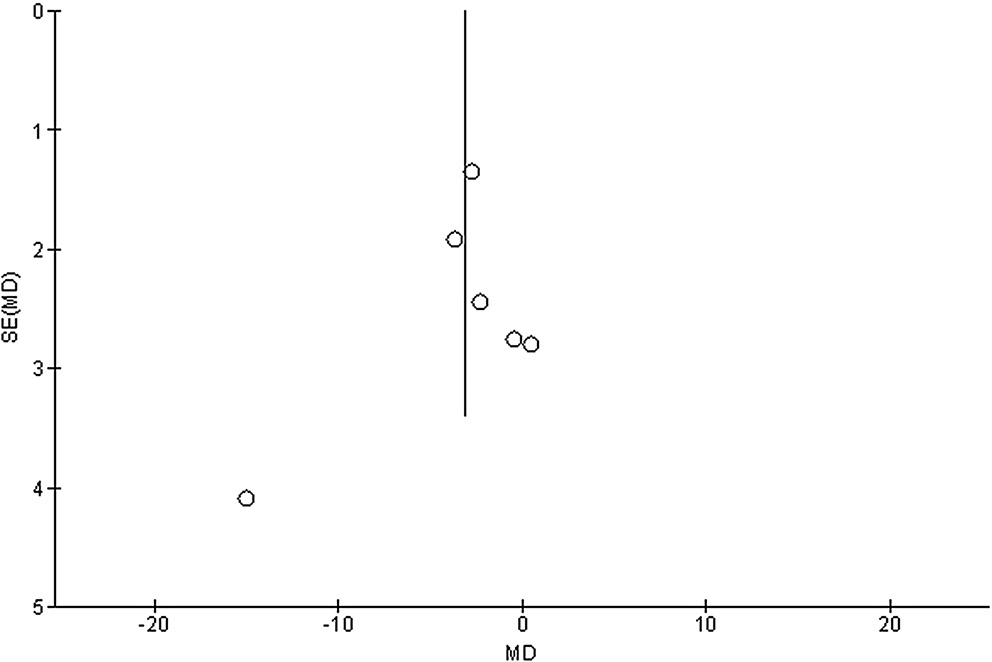

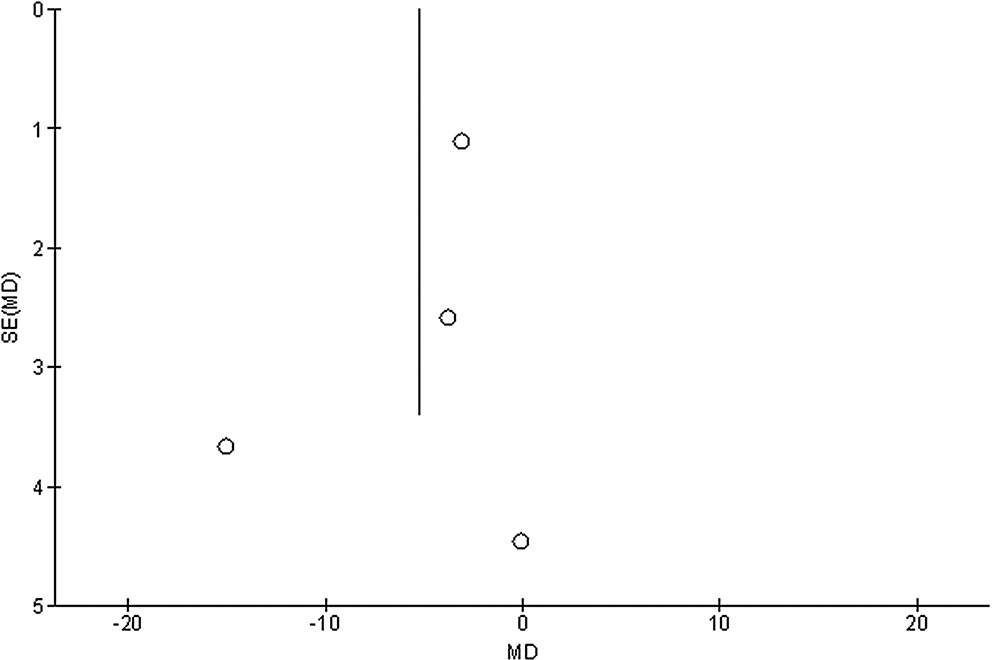

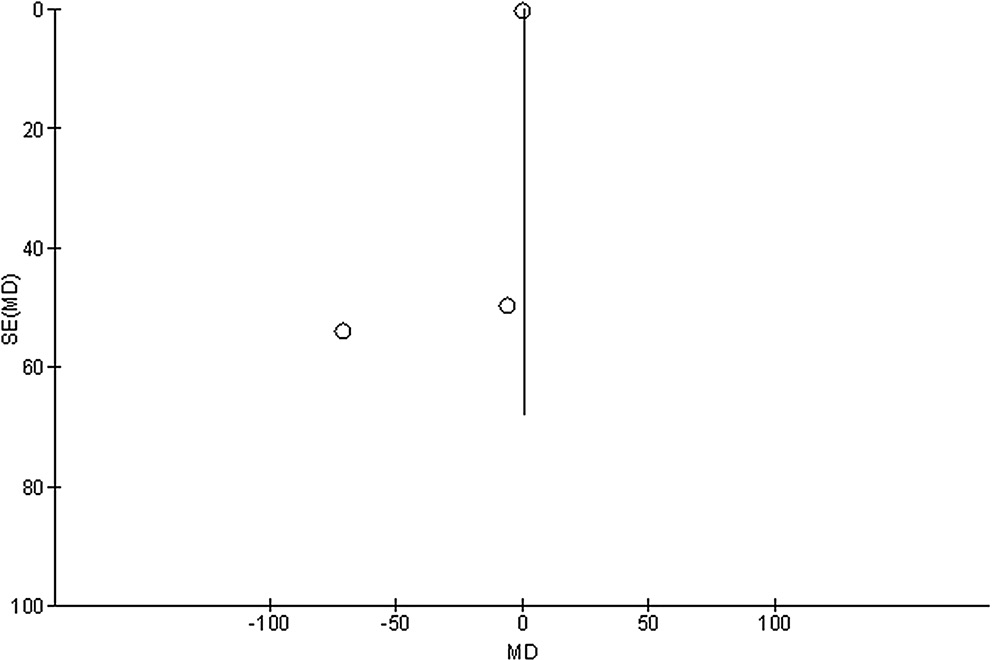

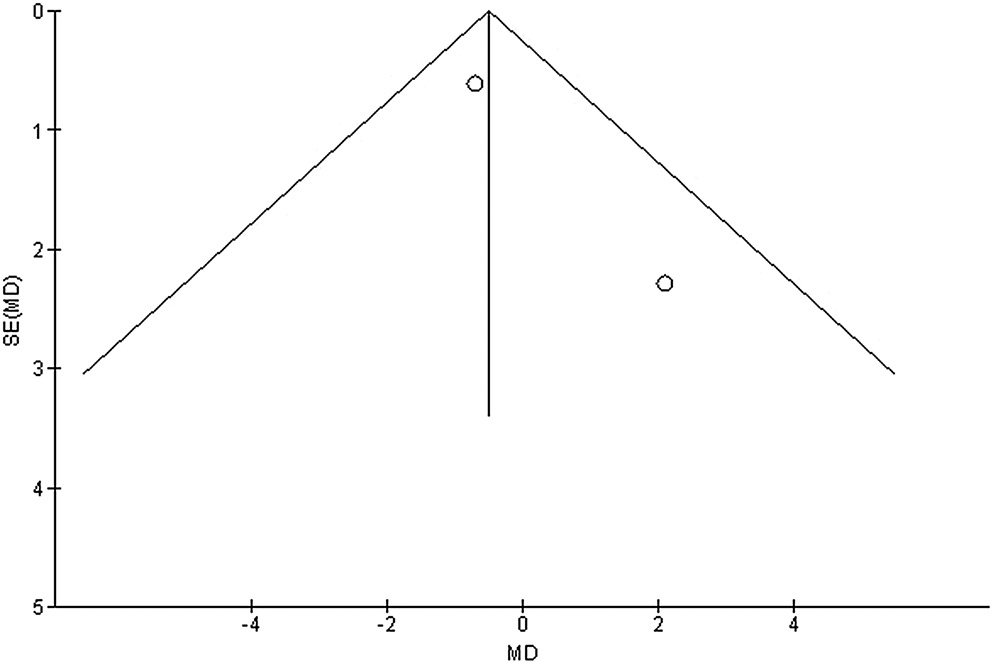

Publication bias was measured both qualitatively and statistically using the funnel plots and the Egger’s regression test, which display the logarithm of ORs or MDs compared to their standard errors (publication bias was considered for p = 0.05).47

Certainty assessment

Two-tailed tests were used to analyze all p-values. The graphs were created and the statistical analysis was conducted using Reviewer Manager v. 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

From a total of 1234 examined studies, 7 articles published between 2003 and 2021 that met the requirements and were included in the meta-analysis were selected.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 Table 2 presents the findings from these studies. A total of 1115 subjects with PD participated in the selected studies’ baseline trials; 633 of them underwent multidisciplinary comprehensive care, while 482 were provided with standard care. Sample size of the analyzed studies was between 79 and 269. Six studies presented data organized according to the HRQL, 4 studies presented data organized according to UPDRS, 3 studies presented data organized according to the medication dosage, and ٢ studies presented data organized according to caregiver strain.

The use of multidisciplinary comprehensive care resulted in significantly better HRQL (MD: −3.17; 95% CI: −5.98–−0.35, p = 0.03, Z = 2.21, degrees of freedom (df) = 5) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 55%), and UPDRS (MD: −5.25; 95% CI: −10.14–−0.37, p = 0.04, Z = 2.11, df = 3) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 71%) compared to the standard care for subjects with PD (Figure 2, Figure 3). Nevertheless, no significant difference was found between multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care for subjects with PD in terms of medication dosage (MD: 0.31; 95% CI: −0.72–١.34, p = 0.56, Z = 0.59, df = 2) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), and caregiver strain (MD: −0.51; 95% CI: −1.69–0.67, p = 0.40, Z = 0.85, df = 1) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 28%) (Figure 4, Figure 5).

Stratified models could not be utilized to examine the influence of some factors on comparison outcomes, such as gender, age and ethnicity, due to scarcity of data on these parameters. After performing quantitative evaluations using the Egger’s regression test and visual inspection of the funnel plot, there was no evidence of publication bias (p = 0.85, p = 0.83, p = 0.89, and p = 0.91, respectively, for HRQL, UPDRS, medication dosage, and caregiver strain) (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9). Nevertheless, the bulk of the included randomized controlled trials were found to have subpar methodological quality, no bias in selective reporting, and scant outcome data.

Discussion

In the trials included in this meta-analysis, 1115 subjects with PD participated in baseline trials; 633 of them received multidisciplinary comprehensive care, while 482 were provided with standard care.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 The use of multidisciplinary comprehensive care resulted in significantly better HRQL and UPDRS compared to the standard care for subjects with PD. Nevertheless, no significant difference was found between multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care for subjects with PD in terms of medication dosage and caregiver strain. Caution should be taken when evaluating the results due to the modest sample size of 2 studies (n = 100) and the small number of studies including the comparisons, e.g., medication dosage and caregiver strain.

This systematic review identified several healthcare delivery models that provide PD patients with multidisciplinary comprehensive care. For a better understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of the various individual models, further information from head-to-head comparisons could be needed. Nevertheless, despite individual variations in the models, earlier studies on other topics, such as chronic lung illness, cancer treatment and chronic renal disease, have effectively analyzed the impact of multidisciplinary comprehensive care.55, 56, 57, 58 Although many concerns are still not answered, there are some important discoveries that might be taken into account for the application of present or future multidisciplinary comprehensive care models in PD.59 Some significant endorsements for the organization of integrated clinical care teams in PD have recently been made using a practice-based evidence approach.60 Additionally, some team members, such as the vascular medicine specialist,61 gastroenterologists,62 pulmonologist, neuro-ophthalmologist, urologist, geriatrician, palliative care specialist, and dentist, have not been recognized as “classic” candidates of a multidisciplinary comprehensive care model for PD.63 The inclusion of these specialties may raise awareness of the complexity of nonmotor symptoms linked to PD and encourage the commencement of more effective referrals to the appropriate healthcare providers.64, 65 According to a recent randomized controlled trial, extended multidisciplinary care is superior to conventional multidisciplinary rehabilitation in PD.66 Multidisciplinary comprehensive care models offer a probability to harmonize healthcare pathways, personalize healthcare utilization based on individual requirements, and improve patient–provider communication as digital infrastructures continue to develop.65 Nevertheless, there are few comprehensive statistics on these novel methods and their use. It is crucial to note that the fundamental objectives of multidisciplinary comprehensive care models might change in the future as researchers continue to look for disease-modifying treatments to slow down, halt or even reverse the neurodegenerative process linked to PD. The team makeup and overall design of multidisciplinary comprehensive care programs may need to be reviewed whenever major advancements in this area are made and some method of disease modification is truly available.

This meta-analysis assessed the results of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD. More homogeneous and larger study samples are necessary in such investigation. This was likewise emphasized in a previous work that employed a similar meta-analysis technique and yielded advantageous outcomes for multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care for subjects with PD.66, 67 Since in the present meta-analysis it was impossible to define whether the differences in gender, age and ethnicity are related to the outcomes, future randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate these factors.

Limitations

Since several studies identified during the search were not included in the systemic review, there might have been a selection bias. However, the removed publications did not meet the necessary inclusion criteria. The sample size for 2 of the 7 chosen papers was less than 100. Furthermore, we were incapable to determine whether factors such as age, gender or ethnicity affected the outcomes of the study. The meta-analysis aimed to compare the outcomes of the standard care group with the multidisciplinary comprehensive care group for subjects with PD. The incorporation of data from earlier studies could have added bias due to incomplete or inaccurate data. Potential sources of bias included the nutritional status of the participants as well as their age and gender characteristics. Regrettably, some unpublished papers and missing data can bias the studied results.

Conclusions

The use of multidisciplinary comprehensive care resulted in significantly better HRQL and UPDRS compared to the standard care for subjects with PD. Nevertheless, no significant difference was found between multidisciplinary comprehensive care and standard care for subjects with PD in terms of medication dosage and caregiver strain. Thus, we encourage the use of multidisciplinary comprehensive care for PD subjects. Communication between team members is an important constituent of multidisciplinary comprehensive care and might need tailored solutions. Above all, maintaining the subject-centered approach in any care model requires constant feedback and availability of modification mechanism in which the subjects and caregiver play equally vital roles.

Availability of data

The corresponding author agrees to make the meta-analysis database available upon reasonable request.