Abstract

Background. Bone mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC)-derived exosomes (B-exos) are attractive for applications in enabling alloantigen tolerance. An in-depth mechanistic understanding of the interaction between B-exos and dendritic cells (DCs) could lead to novel cell-based therapies for allogeneic transplantation.

Objectives. To examine whether B-exos exert immunomodulatory effects on DC function and maturation.

Materials and methods. After mixed culture of BMSCs and DCs for 48 h, DCs from the upper layer were collected to analyze the expression levels of surface markers and mRNAs of inflammation-related cytokines. Then, before being collected to detect the mRNA and protein expression levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), the DCs were co-cultured with B-exos. Then, the treated DCs from different groups were co-cultured with naïve CD4+ T cells from the mouse spleen. The proliferation of CD4+ T cells and the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells were analyzed. Finally, the skins of BALB/c mice were transplanted to the back of C57 mice in order to establish a mouse allogeneic skin transplantation model.

Results. The co-culture of DCs with BMSCs downregulated the expression of the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and CD80/86 costimulatory molecules on DCs. Moreover, B-exos increased the expression of IDO in DCs treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The proliferation of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells increased when cultured with B-exos-exposed DCs. Finally, mice recipients injected with B-exos-treated DCs had significantly prolonged survival after receiving the skin allograft.

Conclusions. Taken together, these data suggest that the B-exos suppress the maturation of DCs and increase the expression of IDO, which might shed light on the role of B-exos in inducing alloantigen tolerance.

Key words: exosomes, tolerance, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

Background

Bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) have multipotent abilities – they can form bone, adipose and other mesenchymal tissues.1 In addition to these differentiation capabilities, BMSCs possess immunomodulatory properties, including the ability to modulate immune cells, such as T cells, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) in a non-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted manner.2, 3, 4 Several studies indicated that the immunosuppressive effect of MSCs occurs through paracrine or cell-to-cell contact mechanisms.5

Exosomes (exos) are small membrane vesicles, of 40–150 nm, released into the extracellular medium upon fusion of late multivesicular endosomes with the plasma cell membrane.6 Accumulating evidence has suggested that compared to BMSCs, exosomes have a stable biological activity and a low risk of immunological rejection.7

Dendritic cells are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that play a prominent role in the development of T cell immune responses.8, 9 In contrast to the ability of mature DCs (mDCs) to stimulate immunity, tolerogenic DCs (tolDCs) are involved in the maintenance of immunological tolerance via T cell unresponsiveness and generation of regulatory T (Treg) cells.10 Another study showed that MSC-exos induced immature DC (imDC) and mDC differentiation into tolDCs with low expression levels of costimulatory markers in vitro.11 However, the mechanism underlying B-exos to induce tolDCs remains unknown. Additionally, whether B-exos from the recipient can drive DC differentiation into tolDCs and induce transplant immunotolerance is not yet clarified.

Therefore, we investigated whether B-exos exert immunomodulatory effects on DC maturation and function by examining the phenotypic and functional features of B-exos-exposed DCs in comparison to their untreated counterparts. We also established an allogenic skin transplant mice model to elucidate the mechanism underlying B-exos-mediated immunomodulation.

Objectives

This study aimed to examine whether B-exos exert immunomodulatory effects on DC maturation and function.

Materials and methods

Animals

Five-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (Animal Center of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China), weighing 25–30 g, were used as experimental animals. All animal experiments conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Use Committee of Shenzhen Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China (approval No. 2021-0057), and performed according to the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

Isolation and culture of BMSCs

The BMSCs were isolated from hind limb bones of 5-week-old C57 mice as described previously,12 and cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM)-alpha growth medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and ×100 penicillin and streptomycin solution (Gibco). The cells were passaged for 3–5 passages (P3–5) using 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) at 78–80% confluency, and used to collect exosomes.

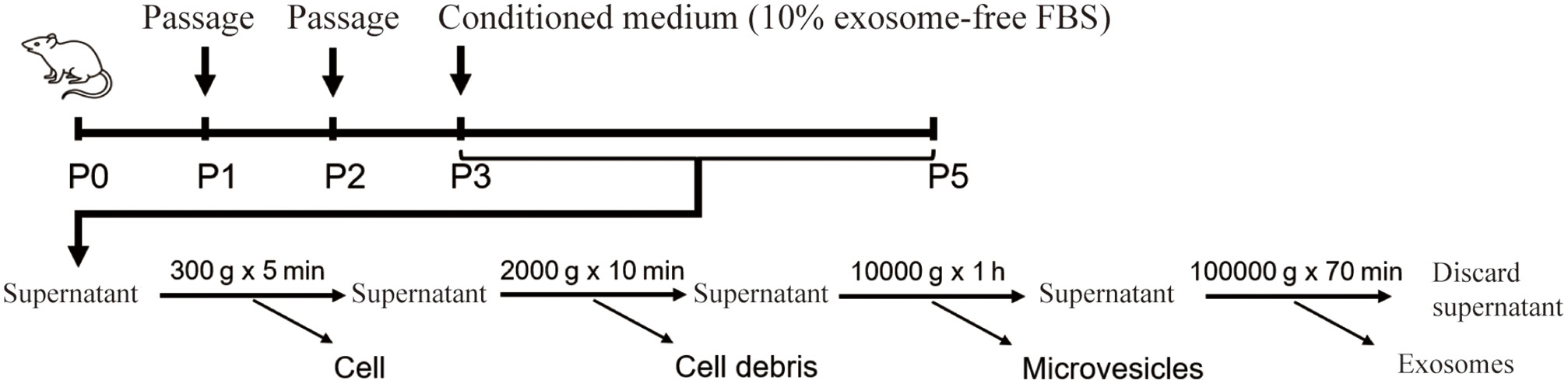

Bovine extracellular vesicle (EV)-depleted medium was obtained by overnight ultracentrifugation of medium supplemented with 20% FBS at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 8 h to eliminate the interference of exosomes from FBS.13 For exosome isolation, P3–5 BMSCs were washed twice with particle-free Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and incubated with fresh medium for continuous culture for 48 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was collected for exosome isolation.

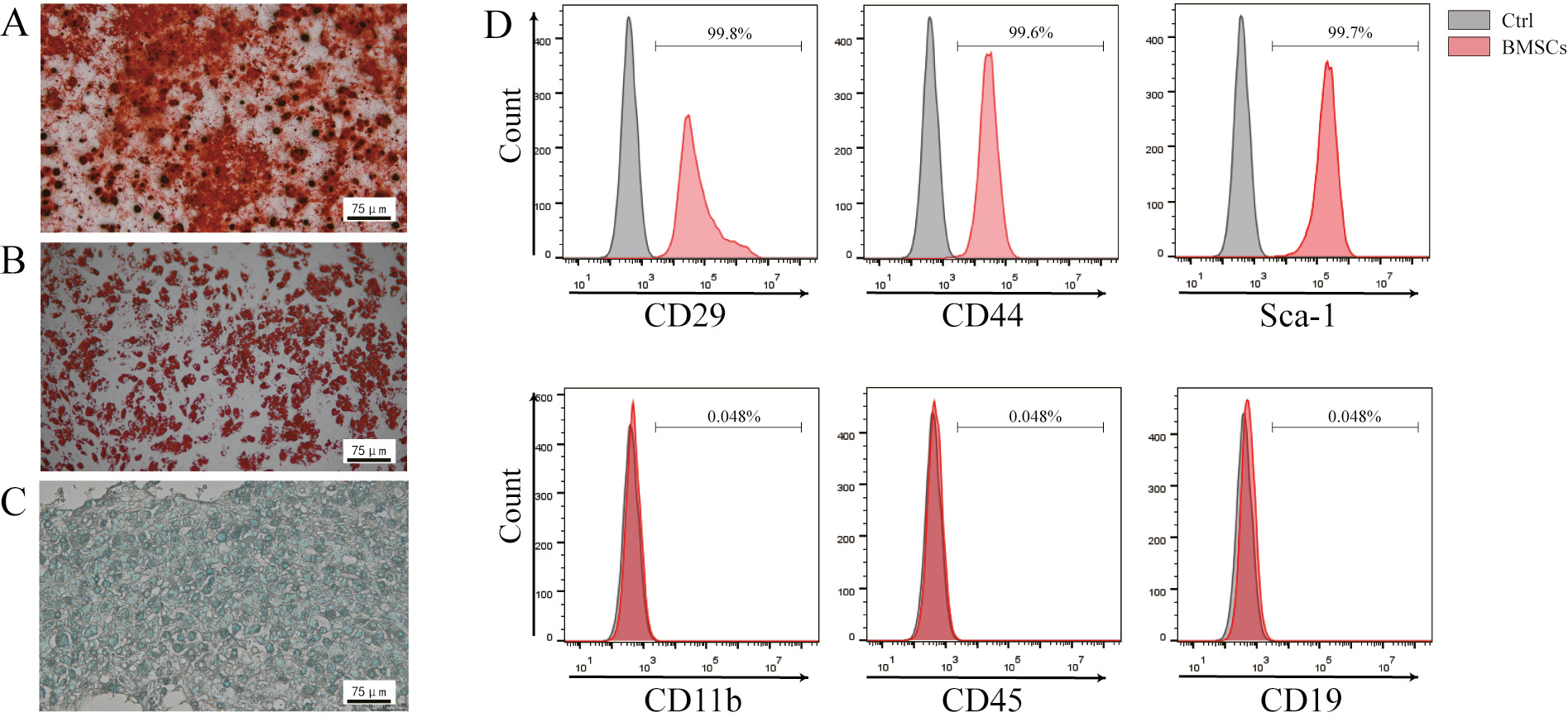

Characterization of BMSCs

Briefly, 106 BMSCs were seeded as a monolayer in 6-well plates. The OriCell™ C57 mouse BMSC adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation kits (catalogs no. MUBMX-90031, MUBMX-90021 and MUBMX-9004, respectively) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cyagen Biosciences Inc., Guangzhou, China). When the adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation processes were completed, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with Oil Red O working solution, alizarin red and Alcian blue (Cyagen Biosciences), respectively, and rinsed with PBS.

Cultivation of BMDCs

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were differentiated from bone marrow as described previously.14 Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs and tibias of 5-week-old C57 mice and cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 20 ng/mL recombinant mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (CK02; Novoprotein, Guangzhou, China) and 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse interleukin (IL)-4 (CK74; Novoprotein). The remaining clusters, loosely adherent to the Petri dish, were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2, and the medium was changed every other day. On day 7, the cells were collected and treated with different protocols, depending on the subsequent planned experiments.

Exosome isolation and analysis

Exosomes were obtained from the supernatant of BMSCs by differential ultracentrifugation, as described previously.13 Briefly, the pellet was obtained by centrifugation of the culture medium at 300 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was clarified as follows: 2000 × g for 20 min, 10,000 × g for 40 min, and finally 100,000 × g at 4°C for 90 min before the resuspension in 50–100 μL of sterile DPBS.

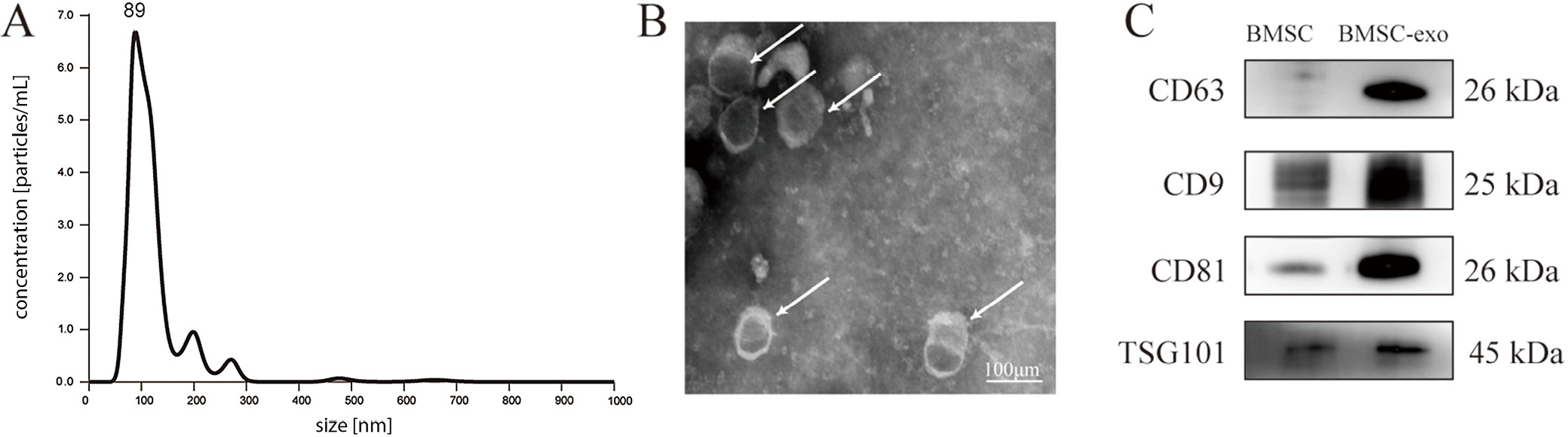

The ultrastructure and size distribution of exosomes were analyzed with transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Nanosight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Briefly, the exosome samples were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 5 min. The mixture was then spotted onto 300-mesh carbon/formvar-coated grids, dried at room temperature, washed with DPBS, and stained for contrast using uranyl acetate (50%) in water at room temperature for 10 min. Then, the exosome size and morphology were observed using a JEM-1011 electron microscope (×25,000 magnification; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

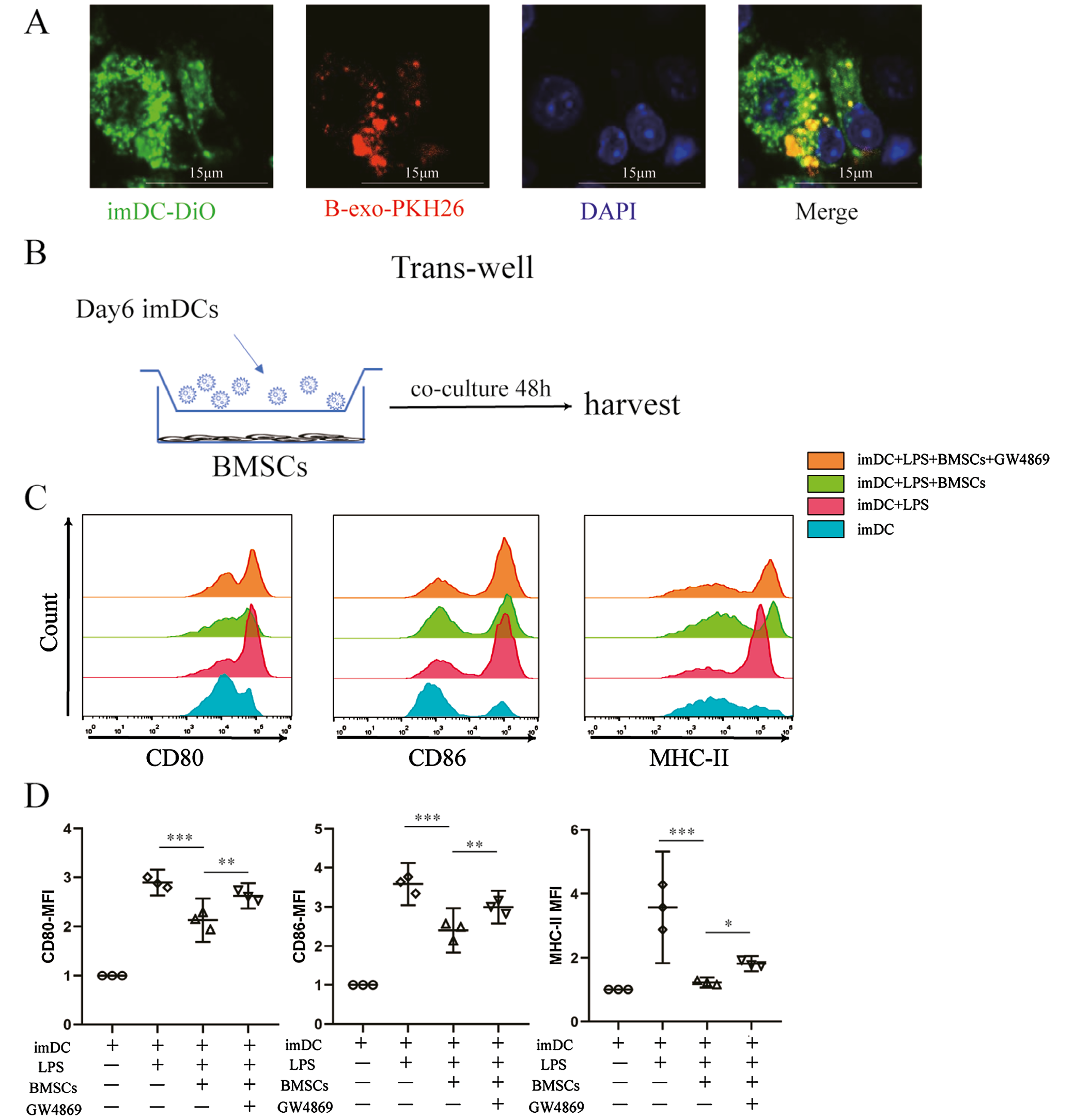

Cellular uptake of exosomes

The concentration of exosomes was determined using the FD™ BCA Protein Quantitative Kit (FDbio Science, Hangzhou, China). Exosomes were labeled with PKH26 using a membrane labeling kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, PKH26 dye was diluted, added to the 10 μg of exosomes in 20-μL DPBS, and then incubated for 5 min after mixing by gentle pipetting. The excess dye was bound with 100 μL of 10% exosome-depleted FBS in RPMI 1640 medium. The exosomes were then diluted to 12 mL with DPBS and pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μL DPBS. The imDCs were incubated with 5 µg/mL of PKH26-labeled exosomes for 12 h and stained with 3,3’-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiO; C1993S; Beyotime, Guangzhou, China) and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, C1005; Beyotime) before being observed with a Benchtop High-Content Analysis System (CQ1; Yokogawa, Musashino, Japan).

Flow cytometry analysis

The P3 BMSCs were digested with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and suspended to a concentration of 1×106 cells/mL in cell staining buffer (#156603; BioLegend, San Diego, USA). Next, the cell suspension was stained with antibodies from BioLegend against CD29-PE (#102207), CD44-PE (#103023), Sca-1-PE (#108107), CD11b-PE (#101207), CD45-PE (#157603), and CD19-PE (#152407) in the dark at 4°C for 45 min.

The imDCs were cultivated in six-well plates at 5×106 cells/well. Dendritic cells were left untreated (as a control) or stimulated with 1 mg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS), 5 μg/mL of BMSC-exos, or 1 mM 1-methyl-L-tryptophan (1MT; Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h. Dendritic cells treated with LPS for 48 h and harvested at day 7 will represent mDC. Dendritic cells in different groups were then incubated with the following anti-mouse antibodies (BioLegend): fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11c (#117305), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD80 (#104707), -CD86 (#159203), and -MHC II (#116407). Subsequently, the cells were stained and observed using a Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA). Data were analyzed with FlowJo v. 10 software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, USA).

Intracellular staining was performed with a Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (KTR201-100; Liankebio, Hangzhou, China). Tregs were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5), APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD25 (PC61.5), and PE-conjugated anti-mouse Foxp3 Ab (3G3) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The populations of Tregs in the co-cultured cell samples were defined as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+.

Co-culture of BMSCs and DCs

in a transwell system

Bone mesenchymal stem cells were cultured in complete medium in the lower well of transwell chambers (pore size: 0.4 μm; Corning Costar; Corning, Corning, USA) to 80% confluency. Then, the medium was replaced with a complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% exosome-depleted FBS. For inhibition of exosome generation, BMSCs were incubated with 20 μM GW486915 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h, and the medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 containing 10% exosome-depleted FBS before co-culture. Subsequently, BMSCs were cultured in the lower compartment, while DCs were cultured in the upper compartment to avoid cell-to-cell contact. Dendritic cells were harvested for further experiments after co-culturing in the transwell system for 48 h.

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from the isolated exosomes or DCs from differentially treated groups using the Whole Cell Lysis Assay (KeyGen Biotech, Nanjing, China), and the concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (FD2001; Fude, Hangzhou, China). The lysates were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (EMD Millipore, Burlington, USA).

After blocking with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) buffer at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies at 4°C overnight (Abcam, Cambridge, UK): TSG101 (1:1000, ab125011), CD81 (1:1000, ab109201), CD9 (1:2000, ab92726), CD63 (1:1000, ab217345), and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) (1:1000, ab277522). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (1:10,000, ab205718; Abcam) and developed using BeyoECL Star (Beyotime). The intensity of the immunoreactive bands was analyzed using the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA).

Co-culture of DCs and naïve CD4+ T cells for differentiation of Tregs

Naïve CD4+ T cells were purified from pooled single-cell suspensions of C57 spleen using a mouse naïve CD4+ T cell isolation kit (#480039; BioLegend). These purified naïve CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with DCs from differentially treated groups at an optimal ratio described previously.16 Then, 1MT, a selective IDO inhibitor, was added to the medium in the 1MT group before co-culture. The cells (T cell 106 and DCs 2×105) were cultured in 24-well plates with a total volume of 1 mL/well of culture medium. The medium was refreshed on days 3 and 5, and the cells were harvested for flow cytometry analysis on day 5.

Real-time quantitative polymerase

chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from DCs in different groups using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s protocols. The RNA quantity and quality were measured on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific). An equivalent of 1 µg RNA was reverse-transcribed using a reverse transcription kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using a PerfectStart Green qPCR SuperMix kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) on an ABI-7500 machine (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primer pairs are listed in Table 1. The data were analyzed using SDS relative quantification software (v. 2.2.2; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative fold change was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method.17 All reactions were performed in triplicate and normalized to the expression of the internal control Actin.

Allogenic skin transplant

Full-thickness skin transplantation in mice was performed as described previously.18 Briefly, the donor mouse (BALB/c) was anesthetized, and the back skin from the hip to the neck was harvested and cut into 15-mm × 15-mm grafts. For the recipient (C57BL/6), 5×106 DCs were given via the tail vein on postoperative day (POD) 0. The recipients in the positive group were given the same amount of PBS via the tail vein on POD0. Ten recipients were randomly assigned to each group. A 10-mm × 10-mm to 15-mm × 15-mm square of skin was cut superficially after anesthesia. The graft from the donor was positioned on the graft bed, and 8 sutures were placed on the corners and the middle of each edge. Finally, the recipient mouse was wrapped in an adhesive bandage with a folded gauze over the graft. Signs of rejection were monitored daily. On POD12, skin and spleen samples were harvested for the analysis.

Histopathology

On POD12, skin samples were collected and animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, processed in graded alcohols, sectioned into 5-μm-thick slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). All slides were reviewed by an expert veterinary pathologist in a blinded manner.

Statistical analyses

The data are expressed as the means with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Normal data distribution within the compared groups was verified with the use of the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variance among the groups was evaluated with the use of the Levene’s test. These results were provided in Supplementary Table 1 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7664412) Three independent experiments were performed for validity, and at least 3 samples per test were taken for statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with the least significant difference (LSD) test. Graft survival was compared through Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test. The value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v. 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA) and IBM SPSS v. 23.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

Identification of BMSCs and B-exos

Bone mesenchymal stem cells from C57 mice could be induced towards osteogenic and lipogenic differentiation (Figure 1A–C). The results of flow cytometry verified that the cells used in our experiment expressed identical BMSC markers in line with the definition of BMSCs (Figure 1D).11

Then, exosomes were isolated from the supernatant of P3–5 BMSCs according to the protocol presented in Figure 2. The TEM, nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and western blot analysis were used to analyze the ultrastructure, size distribution and specific protein, respectively. The results showed that the exosome size was about 89 nm (Figure 3A), and the characteristic saucer shape was revealed with TEM (Figure 3B). Additionally, the expression levels of CD63, CD9, CD81, and TSG101 were more abundant in the exosome protein lysate compared to their parental cell protein lysate (Figure 3C). These findings indicated the successful isolation of BMSCs and exosomes.

Exosome uptake and the effects on attenuation of DC maturation

To assess whether B-exos interact directly with DCs from C57 mice, imDCs differentiated from bone marrow were incubated with PKH26-labeled exosomes and monitored with fluorescence microscopy imaging for over 12 h. We observed that the cells endocytosed the exosomes and became fluorescent at 12 h (Figure 4A). These findings implied that B-exos have the potential to communicate directly with allogenic imDCs.

Next, we investigated whether B-exos affect the phenotype and function of mDCs through an indirect contact with BMSCs in vitro in transwell chambers (Figure 4B). The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) shift showed a significant decrease in MHCII, CD86 and CD80 in DCs co-cultured with BMSCs compared to that of mDCs; however, these effects were attenuated when BMSCs were treated with GW4869, the exosome inhibitor (Figure 4C,D).

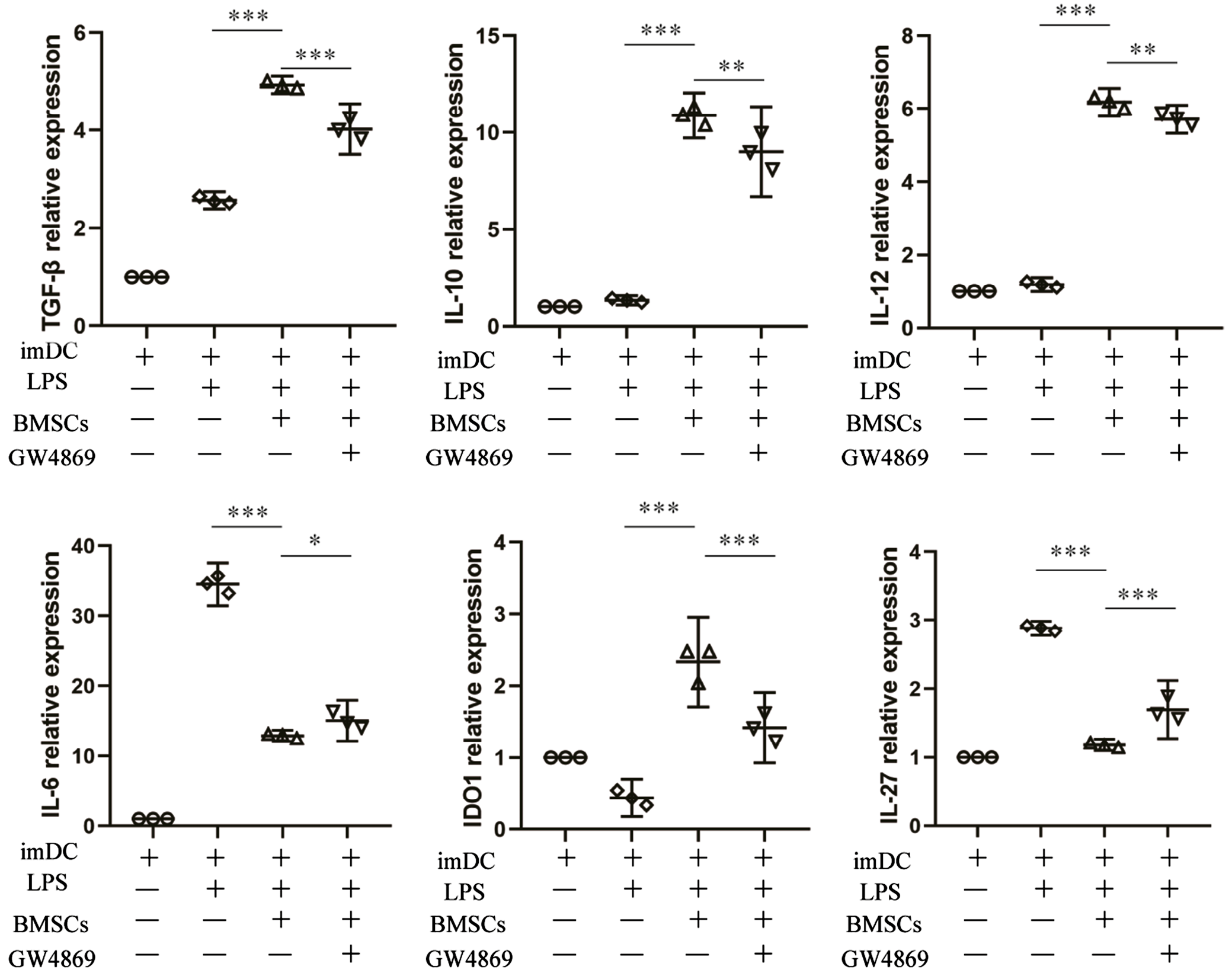

Then, we performed RT-qPCR-based immune profiling of DCs from different groups. The BMSC-exposed DCs showed significantly increased transcripts of several immune-modulatory genes, including IL-10, IL-12 and TGF-β, whereas transcripts of IL-27 and IL-6 were decreased compared to mDCs. However, these phenomena were attenuated after the treatment with GW4869 (Figure 5).

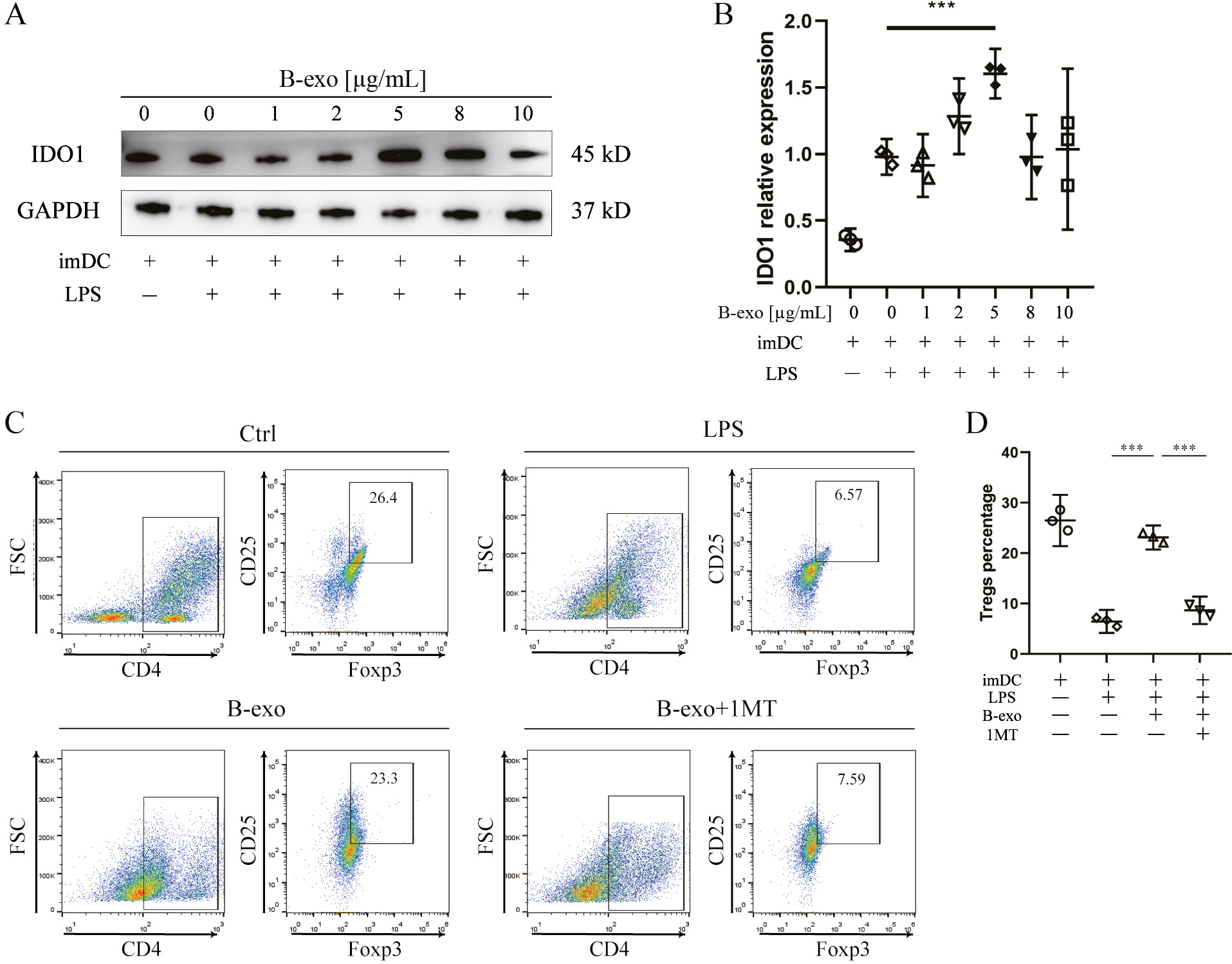

IDO expression is increased during B-exos-induced differentiation of dendritic cells

Since BMSC-exposed mDCs increased the expression of IDO, we investigated the involvement of IDO in the induction of tolDCs by BMSC-exos. The exosomes were purified from BMSC supernatants and co-incubated with imDCs treated with or without LPS (5 μg/mL) for 48 h. Then, we analyzed the effects of different doses (1, 2, 5, 8, or 10 μg/mL) of BMSC-exos. Surprisingly, we found that the expression levels of IDO in mDCs were increased in 2- and 5-μg/mL groups compared to the mDCs group, and the highest expression was obtained in the 5-μg/mL group (Figure 6A,B), considering it the optimal dosage for increasing IDO expression.

Effect of IDO on B-exos-exposed DCs

We also investigated if B-exos-treated DCs could induce Treg polarization. Naïve CD4+ T cells (1×106/well) were isolated from the spleen and incubated with DCs (2.5×105/well) in different groups for 5 days. As shown in Figure 6C,D, the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells decreased in mDCs and 1MT-treated mDCs, but increased in B-exos-exposed DCs. These findings demonstrated that B-exos-exposed DCs induced Tregs by increasing the expression of IDO.

B-exos-exposed DCs

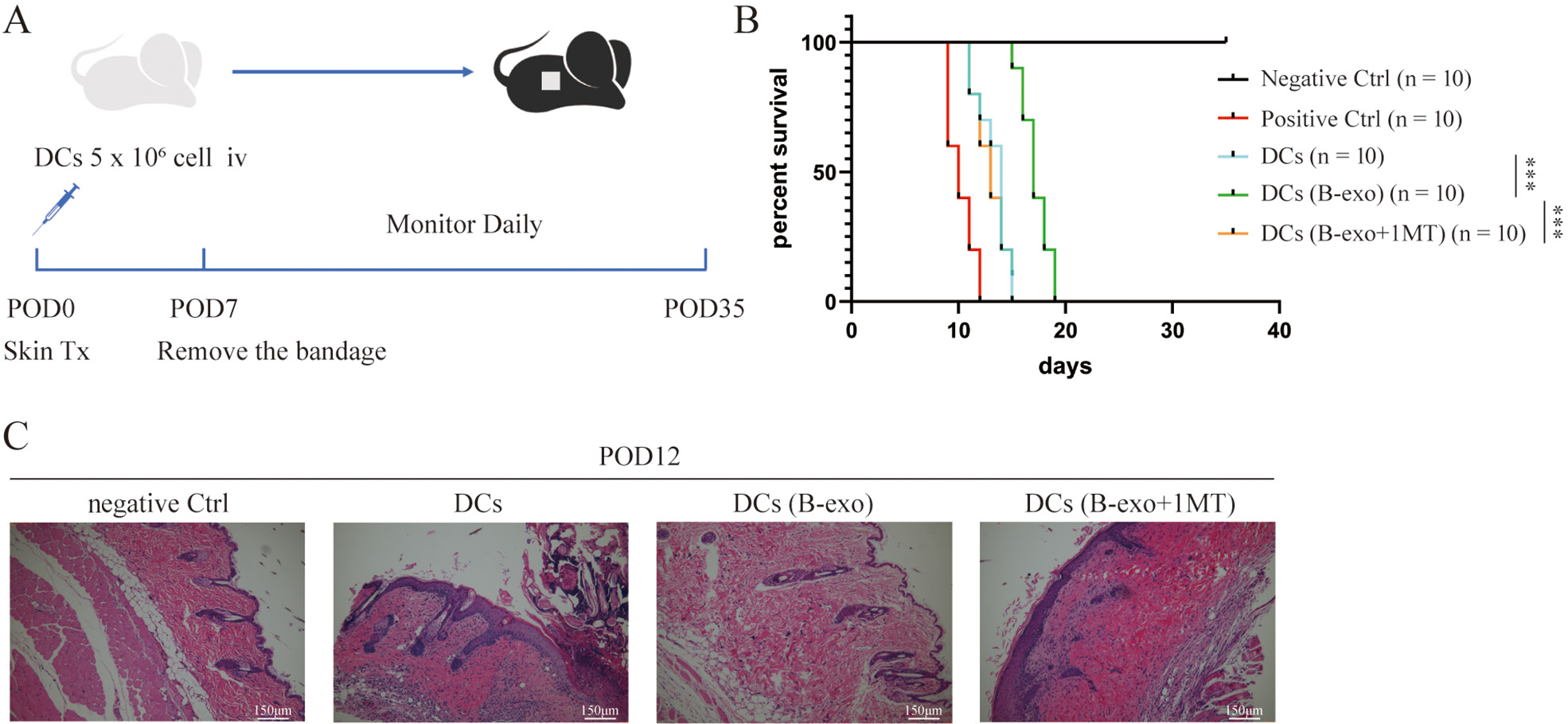

enhanced allogeneic skin graft

Based on the enhancement of Treg polarization by B-exos-exposed DCs, we hypothesized that they could delay the allogeneic skin graft rejection with a concomitant increase in Tregs in the recipient mice. The back skins from BALB/c mice were grafted on BALB/c recipients and followed by caudal vein injections of 5×105 DCs per mouse on POD0 (Figure 7A).

Recipient mice injected with DCs and DCs in the 1MT group rejected allograft skins (median survival time (MST): 14 days and 13 days, respectively; Figure 7B), whereas those injected with B-exos-exposed DCs had significantly prolonged allograft survival (MST: 18 days). Therefore, the DCs in B-exos group significantly improved skin allograft survival.

Histological examination of skin allografts showed slight cell infiltration and preserved graft structure in transplant recipients injected with B-exos-exposed DCs on POD12. However, allografts from recipients injected with mDCs and DCs in the 1MT group showed severe myocyte damage and moderate inflammatory infiltration (Figure 7C).

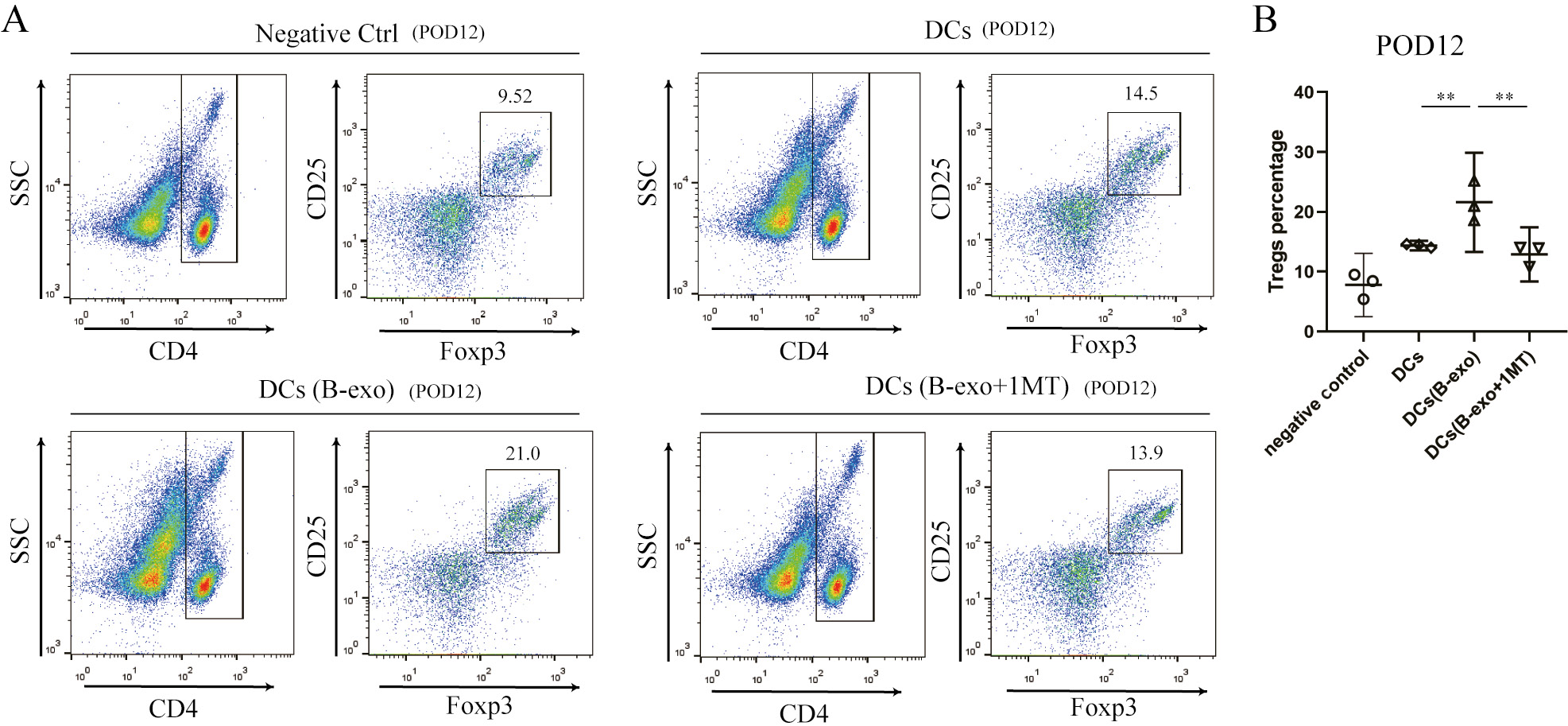

B-exos-exposed DCs induced the proliferation of recipient spleen CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells

To determine if the delayed graft rejection was due to increased Treg polarization, the spleens of the mice from different groups were harvested on day 12 and assayed for Tregs. The level of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells was significantly higher in B-exos-exposed DC recipient animals compared to that of mDCs and DCs in the 1MT group (Figure 8A,B).

Discussion

Due to their potential applications in enabling alloantigen tolerance, MSCs have been investigated thoroughly and found to exert an immunomodulatory effect that influences all cells involved in the immune response.19 Moreover, the paracrine effect is one of the critical mechanisms underlying immune tolerance.20 As a tool of cell-to-cell communication, exosomes transfer biological material between the cells and regulate physiological and pathological conditions.19 Several studies have shown that MSC-derived exosomes can affect the activity of immune cells. A recent study by Zhang et al.21 showed that MSC exosomes mediated cartilage repair enhancing proliferation, attenuating apoptosis and modulating immune reactivity by inducing M2 macrophages and reducing pro-inflammatory synovial cytokines. It indicated that the regenerative and immunomodulatory properties of MSCs were inherited by MSC-exos; which are convenient and recommended for alternative treatments.22 Taking together the results from rescue experiments, we concluded that BMSC-exos, as a form of remote secretion by BMSCs, attenuate the maturation and activation of DCs and induce mDCs into tolDCs.

Dendritic cells are essential in directing immune responses toward either immunity or tolerance.23 Tolerogenic DCs are a subset of DCs that can induce tolerance through various mechanisms, including the induction of Tregs, and could be used in tolerizing immunotherapies.24 Phase I and II clinical trials utilizing tolDCs have been conducted for kidney and liver transplant recipients.25 A key mechanism involved in tolDC-mediated immunosuppression is the expression of IDO-1.26 In addition to suppression of proliferation, IDO competence in human DCs is shown to support T cell regulatory function.27, 28 The current data suggest that when exposed to BMSC-exos, the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells was increased in the BMSC-exos-exposed DC group compared to those in the non-exposed DC group. Collectively, BMSC-exos enhanced the ability of DCs to induce Tregs via elevated expression of IDO. These results confirmed the findings of a previous study, wherein MSC exosomes required monocytes to mediate the differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Tregs.29

Presently, the clinical application of MSCs to improve the prognosis of transplant recipients has broad prospects. Although MSC-derived exosomes have functions similar to MSCs, their direct application is not yet clear. Thus, in the present study, DCs were chosen as recipient cells to modulate allograft tolerance. The regulatory DCs promote liver transplant operational tolerance and are used in cell therapy for many autoimmune diseases.30, 31 However, our cell injection strategy could not achieve long-term transplant survival. Notably, it is difficult to achieve tolerance or long-term survival without the use of immunosuppressants.19 Tolerogenic DCs combined with suboptimal doses of immunosuppressants may achieve specific allograft tolerance and long-term transplant survival.32

Limitations

The present study showed that B-exos induce tolDCs and increase the expression of IDO, but the exact protein or non-coding RNA constituent that promotes this effect is yet to be identified. As a cargo for cell-to-cell communication, the bioactive molecules transferred by BMSC-exos to DCs are the key factors for future studies. The critical factors involved in the induction of tolDCs may be illustrated by RNA sequencing and proteomic analysis along with CRISPR/Cas9 deletion screening or antibody-blocking studies. Besides, a small number of replications is a limitation of this study. In the following experiments, the sample size should be expanded to be able to verify reliably both the normal data distribution and homogeneity of variance. Multiple injection strategy of tolDCs combined with suboptimal doses of immunosuppressants might achieve specific allograft tolerance and long-term transplant survival.

Conclusions

The present study showed that B-exos induce mDCs into a tolDC population with low expression of costimulatory markers and higher IDO expression. In the in vivo study, allograft tolerance is induced by B-exos-exposed DCs with prolonged skin allograft survival.