Abstract

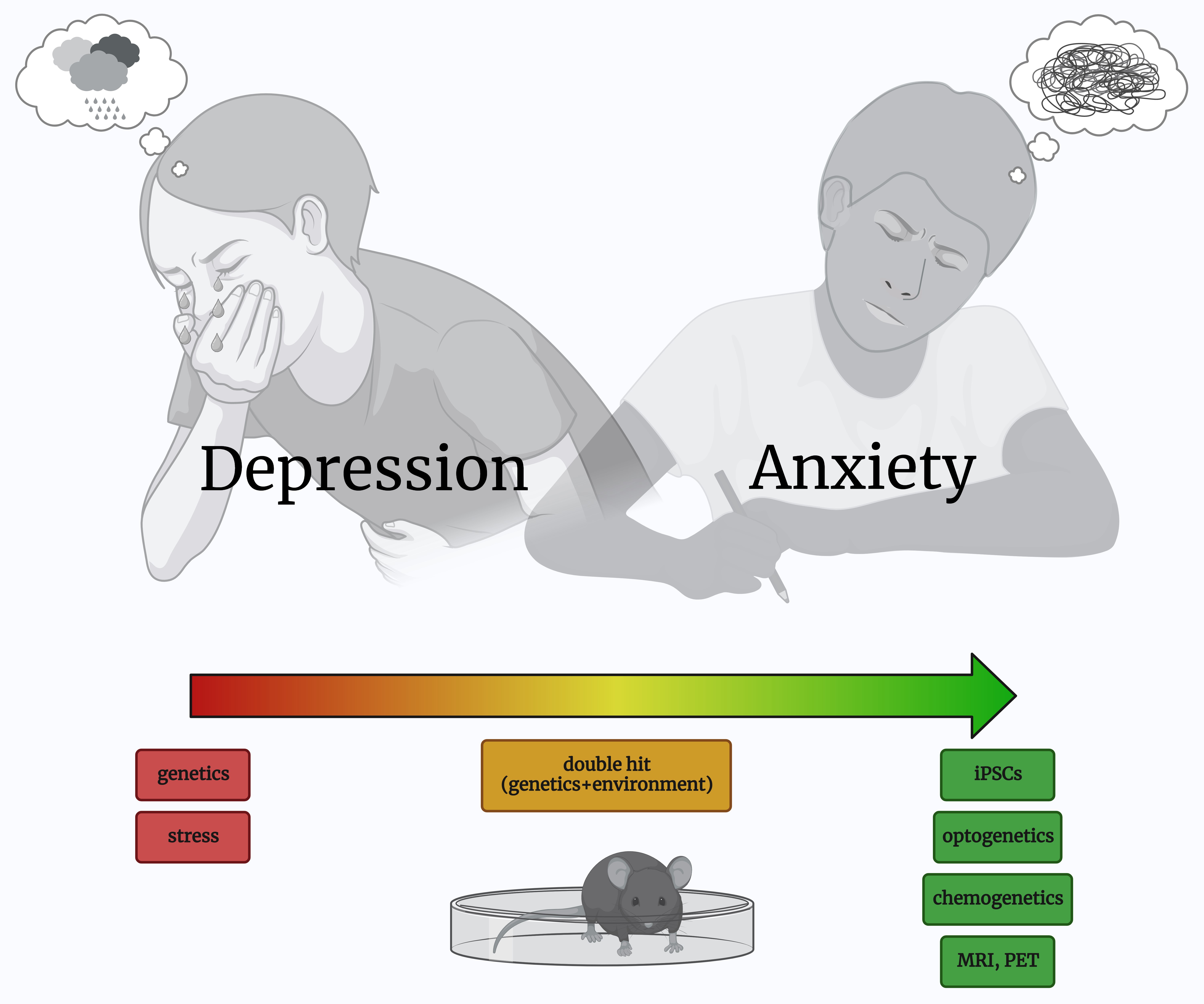

This editorial highlights the limitations of preclinical models in accurately reflecting the complexity of anxiety and depression, which leads to a lack of effective treatments for these disorders. Inconsistencies in experimental designs and methodologies can entail conflicting or inconclusive findings, while an overreliance on medication can mask underlying problems. Researchers are exploring new approaches to preclinical modeling of negative emotional disorders, including using patient-derived cells, developing more complex animal models, and integrating genetic and environmental factors. Advanced technologies, such as optogenetics, chemogenetics and neuroimaging, are also being employed to improve the specificity and selectivity of preclinical models. Collaboration and innovation across different disciplines and sectors are needed to address complex societal challenges, which requires new models of funding and support that prioritize cooperation and multidisciplinary research. By harnessing the power of technology and new ways of working, researchers can collaborate more effectively to bring about transformative change.

Key words: depression, anxiety, PTSD, animal models, translational medicine

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are prevalent symptoms of both systemic diseases and mental illnesses, affecting millions of people worldwide and significantly impacting their quality of life.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The prevalence of these disorders remains high, yet effective treatments are still unavailable.7 The limited success in developing new therapies can be attributed, in part, to the absence of preclinical models that adequately replicate the intricate nature of negative emotional disorders in humans.8 Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of negative emotional disorders, identifying new therapeutic targets and evaluating novel treatments depend heavily on preclinical models, which are vital tools.9, 10, 11, 12 Nonetheless, current preclinical models have limitations that impede their applicability to humans. For instance, the majority of animal models used for anxiety and depression rely on stress induction or genetic alterations that may not accurately reflect the pathophysiology of human conditions.13

This editorial gathers insights from various experts regarding the current challenges and future prospects of preclinical models in understanding negative emotional disorders. We aim to highlight the limitations of existing models and suggest new directions for research to improve the reliability and validity of preclinical models. Furthermore, we seek to promote the use of interdisciplinary approaches to explore the intricate mechanisms involved in the development and maintenance of negative emotional disorders. Ultimately, this editorial intends to stimulate new thinking and innovative ideas to help translate the insights gained from preclinical models into successful therapeutic interventions for these challenging disorders.

Current challenges

in preclinical modeling

The use of animal models in scientific research has been a subject of controversy due to the ethical concerns associated with animal testing.14, 15 Additionally, there is a lack of reliable and valid animal models that can accurately mimic human diseases and responses to drugs.16 Animal models may exhibit different physiological and genetic variations, which can lead to conflicting results that may not translate to humans. This can lead to misinterpretations of research findings and ineffective or even harmful treatments for human diseases.17, 18, 19 Therefore, it is important to continue the development of alternative testing methods that are more reliable, ethical, and accurate in predicting human responses.8, 20

Inconsistent experimental designs and methodologies present a significant challenge to scientific research. Variations in factors such as study size, duration, subject selection, measurement methods, and statistical analyses can generate conflicting or inconclusive findings.21 To address this, researchers should aim to develop rigorous and standardized designs and methodologies that allow for valid and reliable comparisons across studies. This can help promote knowledge advancement and the development of effective interventions.

Identifying a novel target and ensuring safety and efficacy through extensive research studies in drug design and drug discovery are crucial prerequisites for a potential drug to proceed to clinical trials.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Nevertheless, there has been an increasing trend towards overreliance on pharmacological interventions for the treatment of illnesses and conditions in recent years. While there is no denying that medication can be an effective way to manage symptoms and improve quality of life, relying too heavily on drugs comes with its own set of risks and downsides.29 For one thing, overmedication can lead to unnecessary side effects, including fatigue, nausea and dizziness. Additionally, an overreliance on medication can sometimes mask underlying problems that may be better addressed through lifestyle changes, therapy or other non-pharmacological interventions.30 To ensure that patients are receiving the best possible care, it is important to strike a balance between medication and other forms of treatment, and to always prioritize the least invasive approach whenever possible.31

Behavioral and physiological measures are useful indicators for analyzing human activities and responses to different (i.e., threatening) stimuli in the environment. However, there are several limitations to these measures that need to be considered.32, 33, 34, 35 One limitation of behavioral measures is the possibility of social desirability bias, where participants may provide answers they believe will be accepted by others rather than their true opinions or behaviors.36 Moreover, physiological measures can be prone to false readings due to the presence of environmental factors such as noise or electromagnetic interference. Additionally, physiological measures can only provide information about the immediate physiological response and not about long-term effects.37, 38 Furthermore, these measures do not capture the cultural, social and emotional aspects that influence human behavior, which may lead to biases in the interpretation of results.39 Therefore, it is essential to use multiple measures, including self-report data, to improve the accuracy and reliability of the findings.40

Future research directions

To overcome these challenges, researchers are exploring new approaches to preclinical modeling that incorporate the complexity of human negative emotional disorders. One promising strategy is to use patient-derived cells, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), to create disease-specific models. The iPSCs can be reprogrammed from patient cells and differentiated into various types of brain cells, such as neurons and astrocytes, that are relevant to negative emotional disorders.41 These patient-specific models have the potential to provide a more accurate representation of human disease and enable the testing of personalized therapies.42

The development of novel and more complex animal models has been a major focus of research in recent years.8, 43 These models allow researchers to study various diseases and conditions in animals that are more physiologically similar to humans, providing a beneficial tool for the production of innovative treatments and therapies, as well as aiding in the understanding of disease progression and mechanisms. However, it is important to keep ethical considerations in mind when utilizing animal models.44 It is important to balance the potential benefits with ethical considerations to ensure that animal welfare is not compromised.

Integrating genetic and environmental factors is essential in developing strategies to prevent and treat diseases.45 While genetics may play a significant role in an individual’s susceptibility to certain diseases, environmental factors, such as lifestyle, diet and exposure to toxins, also play a crucial role in pathogenesis.46 Understanding the complex interactions between these factors could lead to personalized healthcare interventions and more effective disease prevention and treatment.47 For instance, researchers have found that certain genetic variants may increase an individual’s susceptibility to certain cancers, but environmental factors such as exposure to cigarette smoke or an unhealthy diet may further increase this risk.48 Conversely, lifestyle modifications such as a healthy diet and regular exercise can reduce the risk of disease development, even for individuals with genetic predispositions.49

The incorporation of translational approaches refers to the process of moving scientific advances from laboratory settings to clinical applications.50 This approach aims to improve the efficiency of drug development, minimize the time needed to invent new therapies, and increase the chances of successful clinical outcomes. It involves the integration of various scientific disciplines, advances in technology, and collaboration between academia, industry and regulatory bodies.20 A successful translational approach can lead to the discovery of new biomarkers, identification of disease mechanisms, and advancement of targeted therapies.20 Translational approaches have been instrumental in driving progress in modern medicine, and their ongoing utilization is vital to ensure the creation of safe and effective treatments for various ailments.20

The fields of neuroscience and psychology have seen rapid progress in recent years, thanks to the application of new and innovative technologies. Another approach to improving preclinical models is to use advanced technologies, such as optogenetics and chemogenetics, or the application of noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS), to manipulate specific brain circuits involved in negative emotional behaviors.51, 52, 53, 54 These techniques allow researchers to precisely target brain regions and cell types, which may improve the specificity and selectivity of preclinical models. Optogenetics has allowed researchers to gain unprecedented control over specific cells in the brain, providing a possibility to manipulate and monitor neural activity with precision.55 Chemogenetics applies small molecules to modulate targeted neural circuits and study their functions in vivo.56 These technologies have opened up new avenues for exploring the neural mechanisms underlying behavior, cognition and emotion, and have the potential to lead to new therapeutic interventions for a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Similarly, neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have allowed researchers to visualize and quantify brain activity and structure in unprecedented detail, shedding new light on the neural basis of complex behaviors such as decision-making, creativity and social interaction.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 In addition to these technological advances, it is crucial to consider the heterogeneity of negative emotional disorders when designing preclinical models. Negative emotional disorders can manifest in different ways, and patients may respond to treatments differently.62, 63, 64 Therefore, preclinical models should account for this heterogeneity by incorporating the variability of the disease and the patient’s characteristics. As these technologies continue to improve and evolve, they will undoubtedly play a crucial role in advancing our understanding of the human brain and improving our ability to diagnose and treat brain-related disorders.

Conclusion

Preclinical models play a critical role in improving our understanding as well as treatment of negative emotional disorders, including anxiety, depression and stress-related conditions. These disorders can have significant impact on both mental and physical health.65 Preclinical models provide a controlled environment to study the underlying mechanisms of these disorders, identifying potential drug targets and treatment strategies. Animal models offer insight into the biological mechanisms of negative emotions and allow researchers to develop and test new therapeutic interventions.66, 67 Researchers can study preclinical models to investigate neural circuits and molecules involved in emotional states, and identify changes associated with negative emotional disorders. However, a significant challenge in neuroscience research is creating preclinical models that accurately replicate the complexity of negative emotional disorders in humans. By incorporating patient-specific cells and advanced technologies and accounting for disease heterogeneity, researchers can improve the translational value of preclinical models and expedite the creation of novel treatments. To address the complex challenges the society is facing today, there is a growing call for greater collaboration and innovation in research efforts, which are essential to tackle complex issues like climate change, healthcare, education, and inequality. Breaking down traditional silos and working across different disciplines and sectors can help identify new solutions and approaches. New models of funding and support are also needed to prioritize collaboration and multidisciplinary research, harnessing the power of technology to drive transformative change.