Abstract

The advantages of ultrasonography do not need to be discussed. It is suitable for use in diverse clinical settings and environments by operators with different backgrounds. Recent technological advances have led not only to the enhancement of the diagnostic capabilities of stationary ultrasound systems but also to miniaturization, which in turn led to the introduction of smartphone-sized handheld ultrasound devices (HUDs), designed to be used at bedside to improve and extend the scope of physical examination. Although diagnostic capabilities of HUDs are expanding, according to guidelines, they cannot be perceived as a tool suitable for performing full echocardiographic examination. However, their ultraportability made them essential for the bedside assessment, with the particular emphasis on the bedside focus cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS)-goal-oriented, limited echocardiographic screening. Clinically relevant cardiological targets suggested for HUDs include the assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic function and size, assessment of other cardiac chambers, identification of gross valvular abnormalities, and detection of the pathological masses within the heart cavities. Handheld ultrasound devices may be also helpful in identifying pleural effusion or subpleural consolidations; furthermore, brief ultrasonographic assessment of “lung comets” enables the estimation of the level of congestion. Ultrasound screening for certain vascular abnormalities also appears promising. The limitations of HUDs are rather obvious and caution is needed to distinguish the role of HUD-based bedside-limited scan from comprehensive stationary echocardiography. It appears that the right approach is to treat them as complementary tools proving their capabilities in diverse clinical scenarios.

Key words: handheld ultrasound device, FoCUS, echocardiography

Introduction

The advantages of ultrasonography are unquestionable and its widespread application requires no justification. It is probably the most versatile imaging method in medicine, and its unique characteristics – availability, portability, low cost, and absence of side effects – make it suitable for use in diverse clinical settings and environments by operators with different backgrounds, to examine numerous structures of the human body. Additionally, the fast image acquisition and the possibility for immediate image interpretation can provide relevant clinical information with direct impact on patient management.

Recent technological advances have led not only to the enhancement of the diagnostic capabilities of stationary ultrasound systems. With different clinical scenarios requiring diversified tools, the path of development began to diverge. On the one hand, echocardiographers expect top imaging quality with the implementation of the most sophisticated imaging methods. On the other, when used in a fast-paced reality of emergency room, such traits are left underused and undervalued – it is the portability and simplified yet prompt assessment of patient’s status that counts. Conventional high-end systems, even though designed as mobile, in reality prove difficult to transport. The necessity for bedside examination would result in a time-consuming and impractical transfers of heavy and delicate devices. Thus, the development within the echocardiographic realm may mean more cutting-edge imaging technology but also fitting basic modalities into take-me-everywhere portable devices. While discussing various stages of miniaturization, we should mention the creation of mobile echocardiographs – slightly trimmed down in size yet not in 2D-imaging capabilities group of devices which are more easily transported; laptop-sized portable echocardiographs with slightly limited array of imaging modalities but still sufficient to perform full echo, and finally smartphone-sized handheld ultrasound devices (HUDs) designed for use at bedside to extend and improve physical examination beyond the stethoscope rather than replace standard echocardiography.1, 2

Visual stethoscope was a theoretical concept first mentioned and then implemented in a real diagnostic device in 1970s by Roelandt et al. (Minivisor).3, 4 However, brilliant ideas may require the technology to catch up and it was not until the beginning of 2000s when the first, “pocket size imaging ultrasonograph” suitable for cardiac imaging was introduced (Acuson P10; Siemens AG, Munich, Germany). Other problem which brilliant ideas usually face is that they have to prevail old routines. Two hundred years ago, it was commonly doubted whether the recently invented stethoscope “will ever come into general use, notwithstanding its value5” – and now it has become a symbol of a physician and the diagnostic process.

Fortunately, it is an exaggeration to compare the abovementioned anecdote and the current position of HUDs in modern medicine. However, the question of their status in cardiology is quite intriguing, and finding new possibilities for augmenting diagnostic process with ultrasonography appears very tempting.6, 7

Technical evolution

Finding a niche in a world of imaging diagnostics required investigating uncharted waters. The HUD manufacturers implemented various ideas to meet clinicians needs that other devices could not fulfill. The user interface of HUDs was simplified, with limited image adjustments, as examination was supposed to be based on the predefined presets, optimally with ease of a single-handed operation. Pioneer HUD enabled only 2D imaging with most basic area and distance measurement tools. Initially used 3.7-inch screen now seems outdated, as the technology utilized then does not compare favorably with screens of currently used smartphones. Significant improvements made throughout the years of development included:

– Addition of color – Doppler modality (visual assessment of cardiac valve competence was made possible).

– Introduction of a dual probe combining the features of a sector and linear probe, which enabled the assessment of more superficially positioned structures.

– Radical change of design – certain HUDs are just a probe which could either be connected by a cord or wirelessly with the smartphone/tablet with a dedicated application installed. Such approach had numerous benefits: possibility of fitting the screen size to the clinician’s needs; no risk of the prolonged use of the outdated technology as the screen could be “replaced” with the purchase of a new smart device; easy firmware updates that could fix potential software issues; less complicated disinfection of the device (which proved vital during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic).

– Implementation of M-mode imaging capabilities.

– Streaming a real-time examination for a second opinion or consult, which might prove essential if the HUD operator is an entry-level sonographer.8

– Introduction of the downloadable apps that assist in obtaining correct projections or enable automated evaluation of certain cardiac parameters with the use of machine learning technology. With sufficient computing power of HUDs, it is possible to automatically calculate the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) using an artificial intelligence (AI) module. The first iteration of the software requires only a single 4-chamber view with no border tracing editing. Currently, there are HUDs with more advanced LVEF assessment algorithm which uses 2 apical views: 4-chamber and 2-chamber. Furthermore, manual correction of endocardial borders is possible.

Manufacturers still search for the optimal size of the HUD screen. At first, the miniaturization was perceived as a paramount goal and the devices were constantly becoming smaller and easy for one-handed operation. However, at a certain point, the desired ultraportability clashed with the limited visibility of echocardiographic projections on tiny screens. It appears that a larger device with better screen resolution and equipped with a widened set of diagnostic functions but still not exceeding more or less the size of a tablet combines the best features from both worlds. While it will not fit a white coat pocket, it still remains very lightweight and portable. Most recent HUDs may be slightly bigger than other devices from this group, but are equipped with color Doppler, M-mode, pulsed wave and continuous wave spectral Doppler, previously mentioned AI module for LVEF assessment, and systems tutoring and aiding inexperienced sonographers.9 This makes the separation of a “HUD study” from a “standard study in the lab” less obvious; however, the main objective of using HUDs is improved initial diagnosis rather than replacing comprehensive echocardiography.

Clinical targets for HUDs

The search for the optimal clinical application of HUDs became a focus of numerous published studies. Many of those papers present cardiologists’ outlook on the subject.10, 11 According to the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) guidelines,1, 2 the following findings should be emphasized.

Assessment of LV systolic

function and size

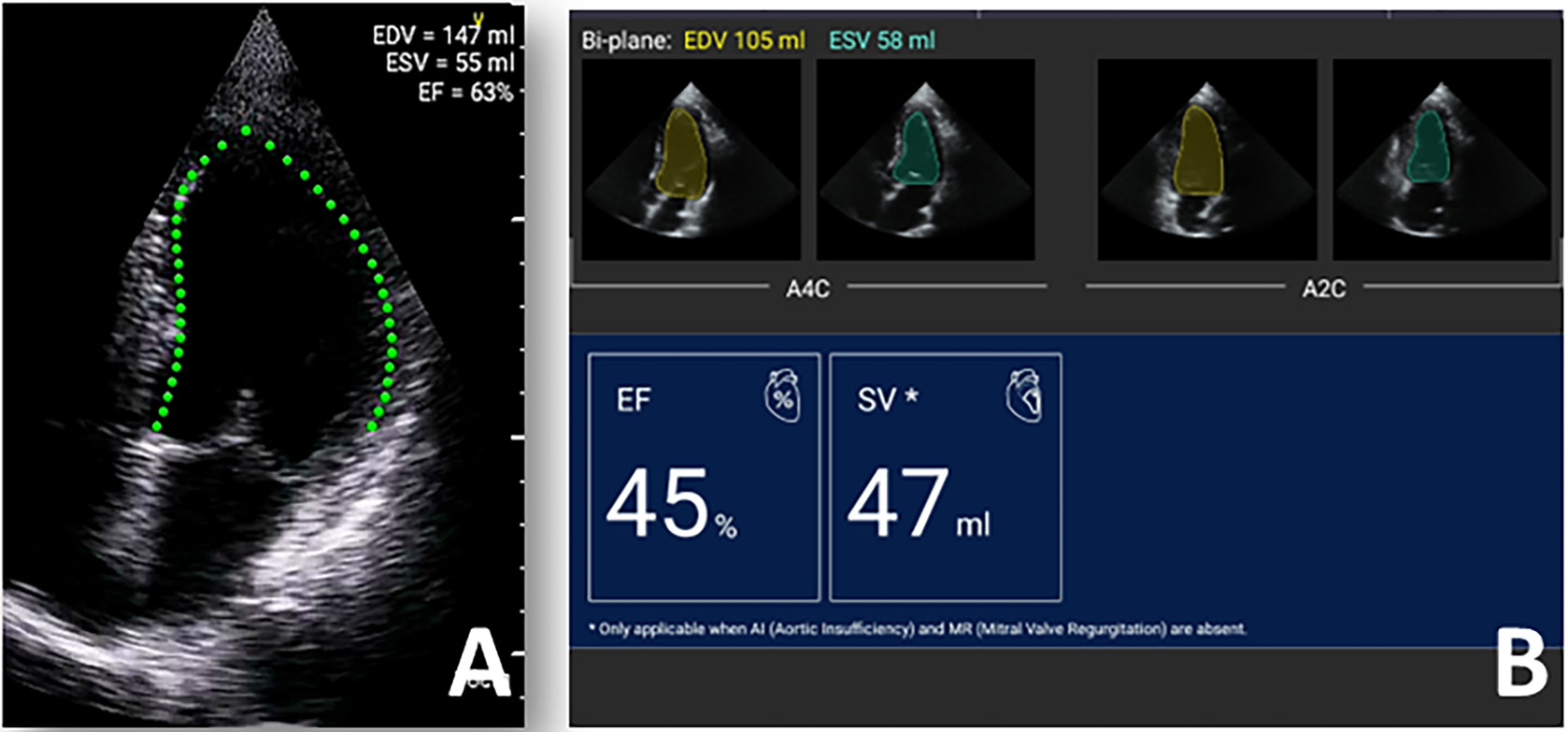

In the majority of cases, the assessment of LV systolic function is qualitative, based on visual estimation of LVEF and regional wall motion. This task proved to be one of main interests of authors attempting to make HUD-acquired echocardiography analysis a fully automated process. Certain HUDs (e.g., VScan Extend; GE Healthcare, Lincoln Park, USA) offer a downloadable application which enables an automated edge detection of left myocardial wall and calculates the end-systolic and end-diastolic left ventricular volumes and LVEF using apical 4-chamber views. Good agreement between HUD and 3D measurement of LVEF on stationary echocardiography was identified12, 13; however, the results largely depended on the quality of acquired images. Furthermore, in almost 12% of patients, the software failed to calculate LVEF.12 A more advanced algorithm available on other device (Kosmos; Echonous, Redmond, USA) performed an automated EF calculation from 2 apical projections, which showed good agreement with measurements using Simpson’s method. Other clinical benefits of this software include high-specificity and high-sensitivity detection of patients with decreased LVEF.14 Improvements to the algorithm also enable a semi-automated EF by editing the endocardial borders, which might prove clinically relevant but requires further validation (Figure 1).

Assessment of other cardiac chambers

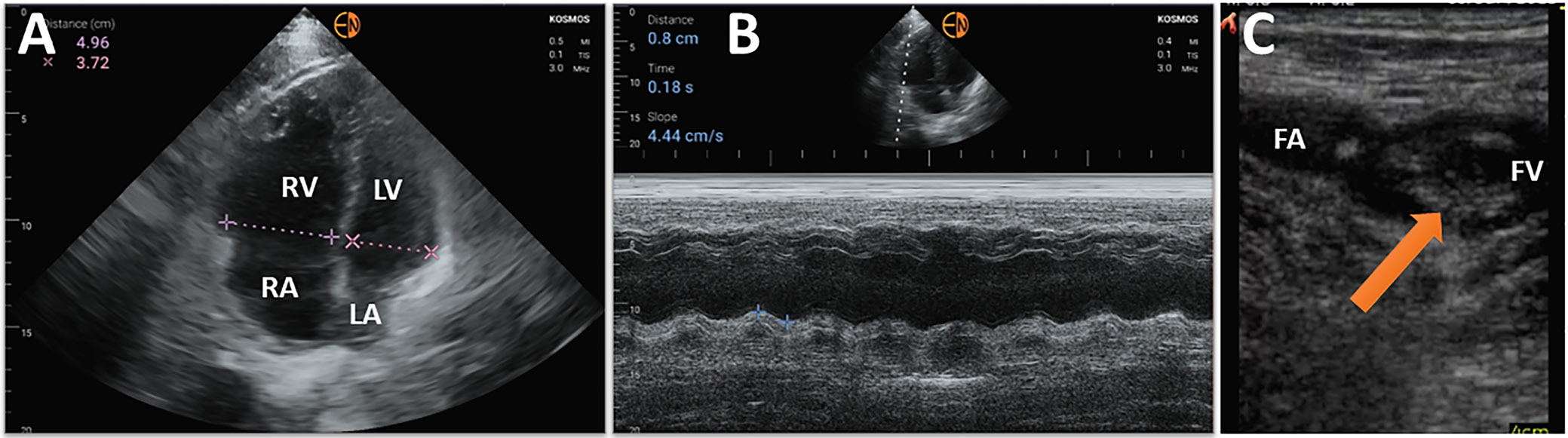

Right ventricle (RV) visualization with HUDs proves more challenging. Variable correlations between HUD and high-end systems to identify RV dysfunction have been reported. Some studies showed that HUDs proved feasible in the initial assessment of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. It was concluded that rapid imaging protocols with HUDs, based, among others, on RV enlargement, allow for improved initial evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism and increase the diagnostic accuracy of clinical risk assessment scores (Figure 2).15, 16

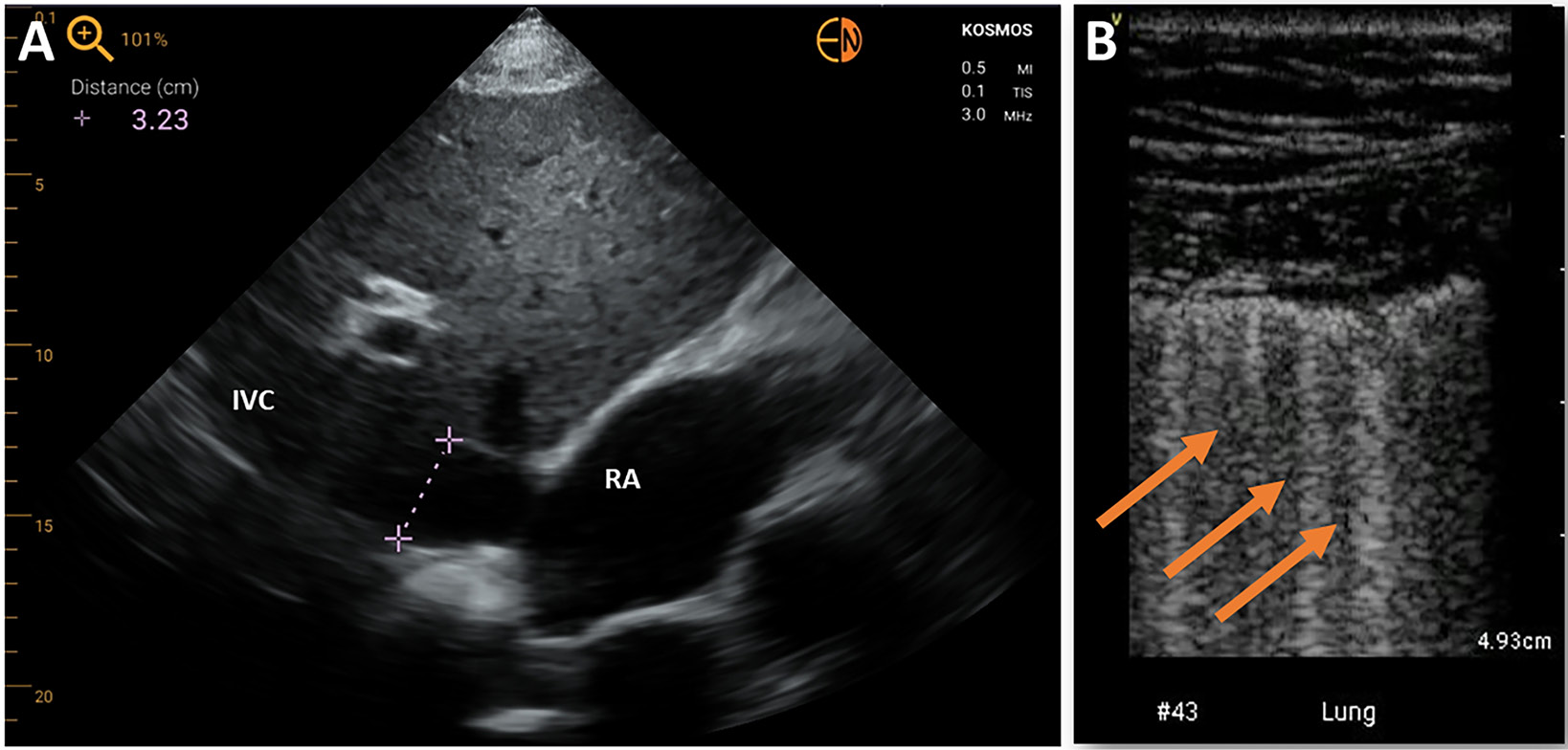

Several studies confirmed the feasibility of HUDs in assessing the width and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava (IVC) parameters used for estimating right atrial filling pressures, also in the setting of critical care unit. It is worth noting that in few studies, HUD operators were trained nurses.17, 18, 19 The presence of left atrium (LA) dilatation as a marker of increased LA pressures was proposed as one of the parameters to be evaluated in critically ill patients when performing their initial assessment.20

Gross valvular abnormalities

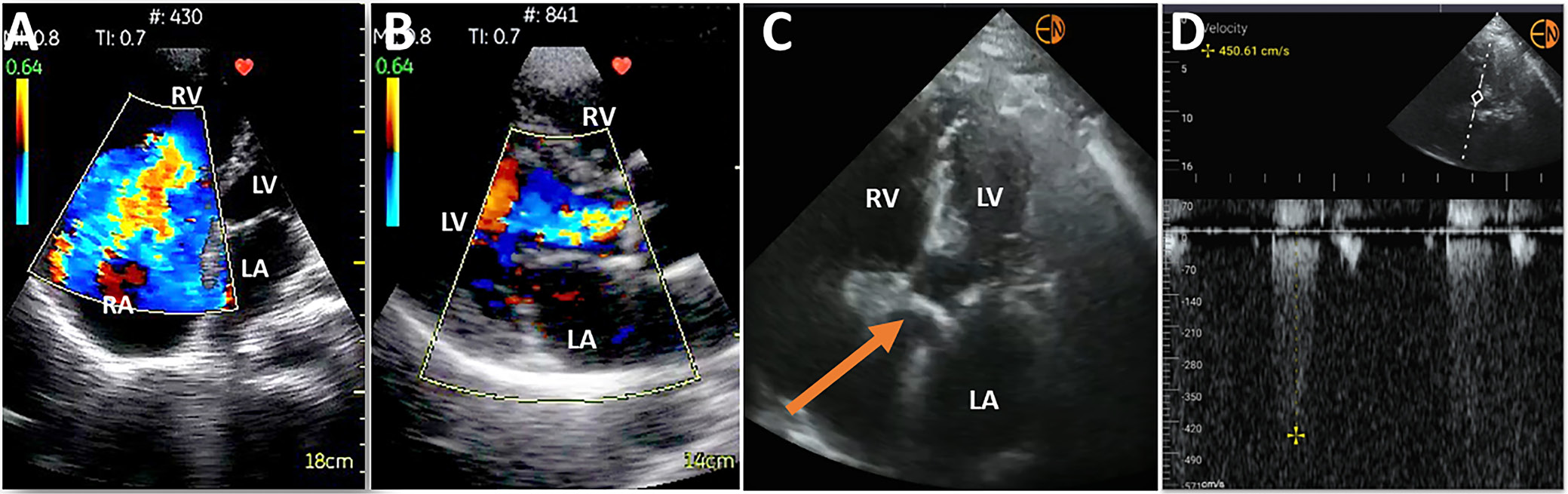

Initially, a valvular assessment could only be qualitative and based on the visual detection of morphologic abnormalities, such as significant calcification or dilated valvular ring. Due to the introduction of the color Doppler modality, such assessment, although still qualitative, became more accurate. Quantitative analysis was recently made available with the implementation of spectral Doppler to a HUD. It was already confirmed that experienced operators can reliably detect clinically significant aortic stenosis (AS) and facilitate AS grading with the use of this HUD, and this modality might prove promising (Figure 3).21

Other specific echo findings

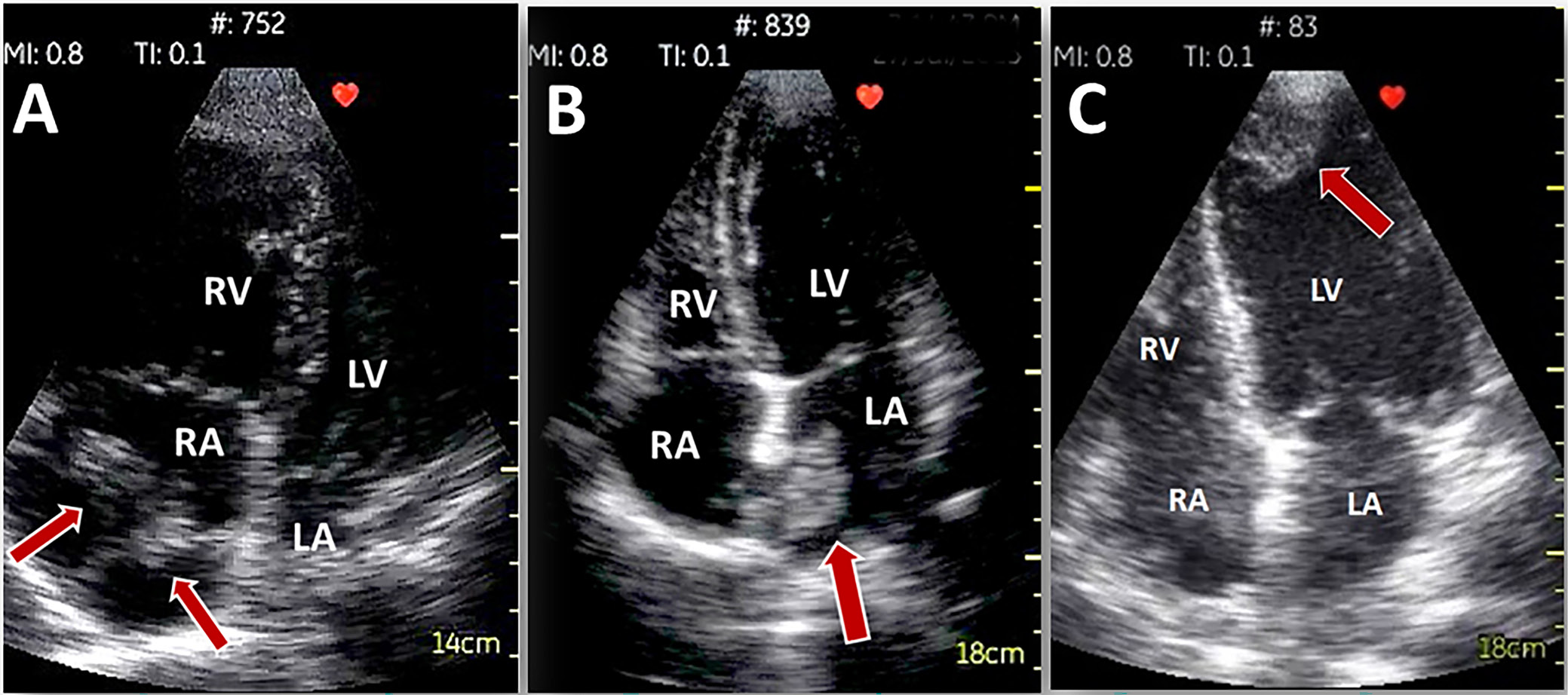

The HUD-derived projections are of sufficient quality to enable the detection of the pathological masses within heart cavities. Although scientific data are mainly obtained from case studies, they show that thrombus in LV,22 masses suggesting the presence of tumors (e.g., myxoma23), or thrombus in transit in right atrium (RA) and RV24 could all be identified. There is a good overall concordance with the conventional echocardiography in the detection and assessment of pericardial effusion (Figure 4).25, 26

Extracardiac findings

The HUD-performed lung ultrasonography became a particularly interesting diagnostic option in the time of COVID-19 pandemic.27, 28 Besides the identification of pleural effusion or subpleural consolidations, brief ultrasonographic assessment of “lung comets” allows the estimation of the level of congestion, which is vital in patients with heart failure (HF) (Figure 5).29

Ultrasound screening for certain vascular abnormalities can also prove clinically relevant. Handheld ultrasound devices proved their feasibility in carotid stenosis evaluation,30, 31 accessing site complications screening after the femoral artery puncture32 or a detection of the aortic root dilatation as a marker of aortic dissection in symptomatic patients. Abdominal aneurysm screening may also be feasible in patients with good substernal visibility.

FoCUS examination

Due to limited diagnostic capabilities of HUDs, it was impossible, according to guidelines, to perceive them as tools that could be used for full echocardiographic examination. However, their ultraportability made them essential tools for the bedside examination, with the particular emphasis on the bedside focus cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS)-goal-oriented, limited echocardiographic examination.33 Such procedure should be treated as an extension of the physical examination. It can be performed in any environment, with a predefined limited protocol, by an operator not necessarily trained in comprehensive echocardiography, but appropriately trained in FoCUS and usually responsible for decision-making and/or treatment process.

Who needs the HUDs?

Non-cardiologist use of ultrasound for rapid, bedside structural assessment of the heart in critically ill patients drew widespread attention for the first time in the early 1990s. It was shown that a readily available, limited echocardiogram carried out by emergency physicians could confer a mortality benefit to those with penetrating cardiac injuries.34 From this narrow scope, non-traditional users of echocardiography such as critical care physicians have expanded the applications of cardiac ultrasound to address a broad array of important clinical questions at the bedside.

The EACVI guidelines emphasize that FoCUS should only be used by the operators who have completed appropriate education and training program, and who fully understand and respect its scope and limitations.33 The FoCUS utilizes a highly restricted protocol that represents a small part of the standard comprehensive echocardiographic examination. Although cardiologists who have completed basic echocardiography training outlined in the EACVI recommendations are qualified to perform echocardiography in all emergency situations, for optimal use of FoCUS, they should be familiar with the FoCUS scope, approach and Core Curriculum. In this regard, they could also benefit from additional training, e.g., in basic lung ultrasound (LUS) and the use of cardiac ultrasound in critical care. In case of other medical professionals, theoretical and practical training is vital; it was observed that learning curve for FoCUS is relatively steep.35

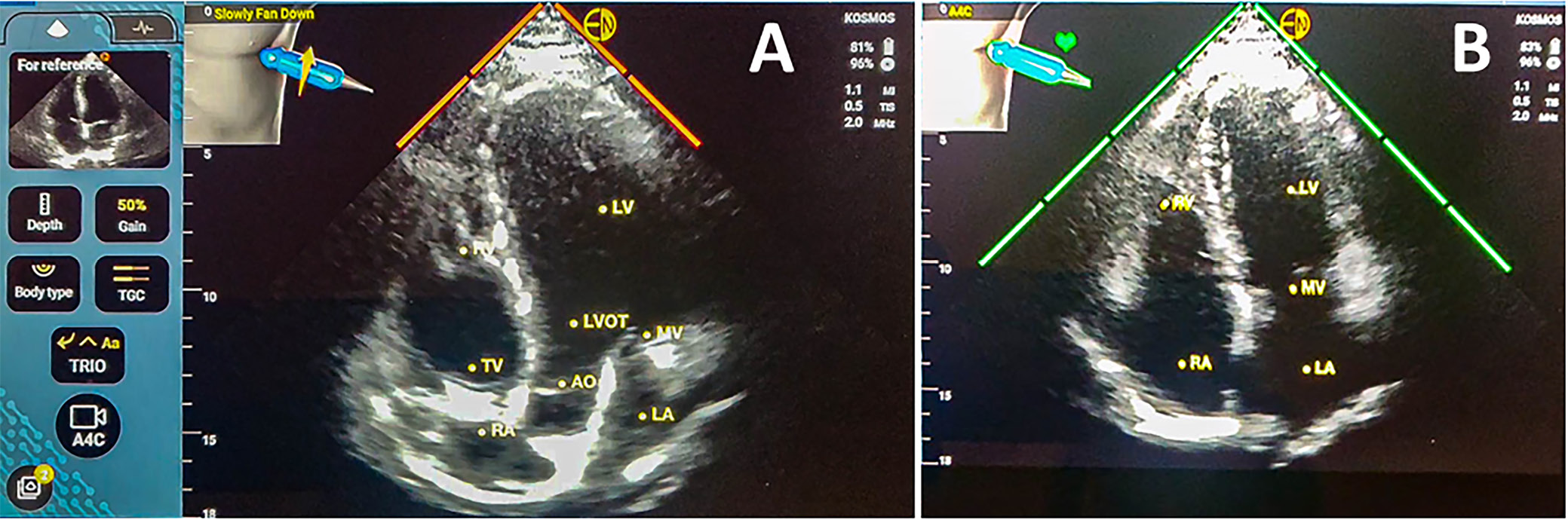

Novel HUDs introduced machine-learning tutorials for the less experienced operators – modality of real-time labelling of the visualized structures. Apical projections can also be assessed using the software algorithm, and in case of the suboptimal quality hints regarding the proper probe orientation are displayed on the device screen (Figure 6).

Other implementations of HUDs

Apart from their clinical usefulness, HUDs are an unequivocally valuable tools for educating and hands-on training of medical students. It was previously confirmed that even a brief training of medical students results in the reliably performed basic ultrasonographic screening augmenting the physical examination.36, 37 Importantly, the learning curve is steep. Proposed use of HUDs by anesthesiologists for the purpose of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) learning also proved effective.38 The HUDs were also introduced as a tool used in numerous screening programs in schools, workplaces and in social campaigns.39, 40, 41, 42 They may also play a prominent role in the development of the contemporary telemedecine – in a study conducted by Dykes et al., the parents of pediatric patients after heart transplant were trained in acquiring images in parasternal short-axis and apical views, which were subseqently sent to an experienced sonographer for assessment. Interestingly, acquired projections were sufficient for the qualitative assessment of LV function.43 Finally, HUDs are efficient, cost-effective screening tool to detect patients requiring full echocardiography.44, 45

Conclusions

In a world where the consumer needs are being created rather than correctly identified, it may be difficult to tell apart between a gadget and a useful tool that might actually improve certain aspects of our lives. Things become even more convoluted in medicine, where the stakes are especially high. The HUDs at first may seem “gimmicky” and having no real substance to back their widespread use. But in reality, they are still passing the test of time being widely used by numerous medical professionals, who would not otherwise be able to introduce the elements of imaging diagnostics into the treatment process. Moving limited echocardiogram out of echocardiography rooms to the bedside created a real challenge to the traditional ‘just a stethoscope’ approach towards more robust bedside screening. Expert sonographers may frown upon the limited set of features, but even them, when facing an immediate threat to patient’s life in a setting of an emergency ward, would be more than happy to perform basic echocardiography rather than rely on a limited set of diagnostic data. The limitations of HUDs are obvious and effort is needed to distinguish indications for the HUD-based bedside-limited scan and comprehensive, in many cases decisive standard state-of-the-art echocardiography. This is, however, the skill of picking the right tool for the job.