Abstract

Background. As dental implants become a more popular treatment option for restoring missing teeth, it is significant for a dentist to understand patients’ level of knowledge toward implants, to avoid potential miscommunication and unrealistic expectations.

Objectives. To determine the knowledge level regarding dental implants among patients applying for prosthetic treatment.

Materials and methods. The study was conducted among patients from the Department of Prosthetic Dentistry at Wroclaw Medical University, Poland. A questionnaire composed of 11 questions was distributed to 232 patients, of which 225 were qualified for the study. The chi-square test of independence (χ2) was used to analyze the association between parameters of interest and groups of patients. The strength of studied relationships was measured with Cramer’s V.

Results. Patients showed limited knowledge of implants. Of the respondents, 75.6% heard about dental implants; however, 40% considered the dental implant as a set of a screw with a fixed crown. The major concern was the high cost (69.4%), followed by the need for surgery (31.2%). The Internet was the most popular source of information. The source of treatment financing has a strong correlation to the willingness to undergo treatment.

Conclusions. The study group demonstrated not a satisfactory extent of knowledge regarding dental implants. Dental professionals should make an effort to provide sufficient information to patients to avoid misunderstandings about the treatment. Measures should be taken to reduce the cost of the procedure and thus increase its availability.

Key words: dental implants, prosthetic treatment, patient knowledge

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Oral Health Status Report (2022), the frequency of edentulism for people aged 60 years and older is 23%, while the rate of people above the age of 20 with complete tooth loss was almost 12% in Poland. World Health Organization report has indicated a proportional and direct relationship between population groups with lower socioeconomic status (social class, lower education level, and income) and oral disease severity (including edentulism), regardless of their country’s wealth. The most common causes of tooth loss are untreated dental caries, periodontal disease, dental trauma, and poor health services.1 The burden of severe tooth loss not only affects masticatory function and appearance but also has an impact on the level of comfort and social life, with many edentulous individuals struggling with involvement in society due to reduced self-esteem and the embarrassment of smiling and speaking.2

The most traditional prosthodontic treatment options for replacing missing teeth include removable partial prostheses, complete prostheses, and fixed appliances such as bridges and implants.3 Dental implants are screws surgically placed in jawbones that provide alternative options for restorations of single tooth gaps, implant-supported overdentures for fully edentulous individuals, and maxillofacial prostheses.4, 5 The broad popularity and acceptance of dental implants as a method of rehabilitation of missing teeth are due to their high rate of treatment success demonstrated by long-term research.6, 7, 8, 9 Thus, it is important to understand patients’ level of knowledge and comprehension of dental implants to enhance patient-provider communication and accept the treatment plan.

In Poland, the differences in the oral health status of the population may result from a limited degree of insurance-covered dental procedures. The Polish public health system only finances prosthetic treatment for removable dentures (replacing 5 or more missing teeth). Other prosthetic procedures, such as crowns, bridges, metal frame partial prostheses, and implants, are fully paid for by patients. Consequently, advanced prosthetic care with dental implants is not accessible for the majority of the Polish population, and beneficiaries of the treatment are mainly the wealthy patients.10

The most common sources of knowledge about dental implants, indicated in different papers, are relatives/friends, dentists, and the Internet.11, 12, 13, 14 However, expectations and willingness to undergo an implant procedure reflect the adequacy of the patient’s awareness.15 Therefore, it is essential for dental professionals to understand patients’ level of knowledge regarding dental implants to avoid potential miscommunication and unrealistic expectations.

Objectives

The present research was conducted to evaluate the level of knowledge and awareness regarding dental implants among patients admitted for prosthetic treatment. There are no reports on this subject in the literature, so this is the first study of this kind on the Polish population. Nevertheless, there are many related studies in other countries. The study hypothesis was that patients admitted for prosthetic treatment had an inadequate extent of knowledge regarding dental implants.

Materials and methods

Study design, area, and population

The study was conducted in the form of a self-administered survey among patients of the Department of Prosthetic Dentistry at Wroclaw Medical University, Poland. Data were collected from November 2022 to February 2023. The Department of Prosthetic Dentistry is responsible for preparing prosthetic treatment plans and directing patients to the Department of Dental Surgery if implants are planned. The inclusion criteria were patients interested in participating in the study and those aged 20 and above. The exclusion criteria were age below 20, mental disability, and returning incomplete questionnaires.

Participants and sample size

The total number of participants involved in the study who met the requirements was 225 (146 women and 79 men). Every patient in the Department of Prosthetic Dentistry waiting hall was invited to participate in the study to avoid sampling bias. All respondents were informed about the aim of the study, which was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients consented to participate.

Survey tool

A total of 232 questionnaires were distributed to the patients, of which 225 were qualified for the study. The survey consisted of 11 questions and was designed to obtain data about socio-demographic characteristics (5 questions on gender, age, and educational background), awareness of dental implants, and attitude to implant treatment (6 questions regarding dental implants) (Table 1).

Statistical analyses

The χ2 test was used to analyze the association between parameters of interest and groups of patients. The strength of studied relationships was measured with phi coefficient and Cramer’s V. Phi was used to examine the association between 2 dichotomous variables and Cramer’s V when there was more than a 2×2 contingency. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The graphics were produced using Microsoft® Excel® 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA).

Results

Demographic structure of the study group

The total study group was comprised of 146 women (64.9%) and 79 (35.1%) men. The largest response group represented people between the ages of 61–70 (36%), the 2nd largest group was over 70 (25.3%), 15.1% were between 51–60, 13.8% between 20–40, and the smallest group was between 41–50 (9.8%). Of all participants, 29.3% had a higher level of education, 63.6% gained secondary education, and 7.1% completed only primary education. Table 1 summarizes the demographic structure of the group.

Knowledge and attitude

In the present study, 75.6 % of the respondents heard about dental implants, of which 65.9% were female and 34.1% were male. There was no significant difference between men and women (p = 0.583) (Table 2), although 24.4% of patients were not aware of implants. The general knowledge of dental implants was measured with 2 questions on what an implant is and where it is anchored in the mouth. Most participants (40%) considered dental implants to be a screw with a fixed crown. The answers “a screw replacing tooth root” and “a denture” were given by 21.8% of the respondents, followed by 6.2% who answered “a crown,” while 10.2% of respondents answered “I had no idea”. The difference between genders was insignificant (p = 0.543).

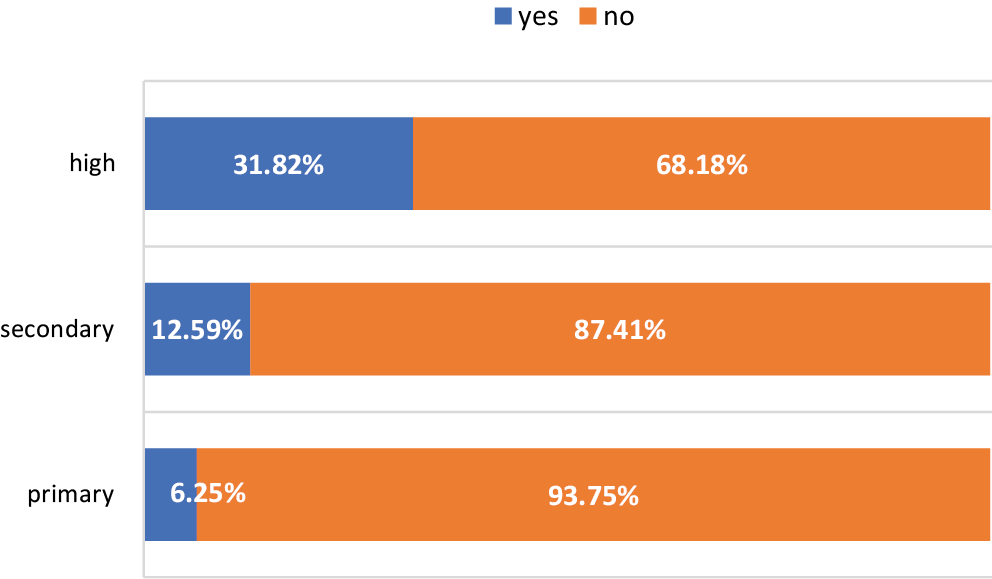

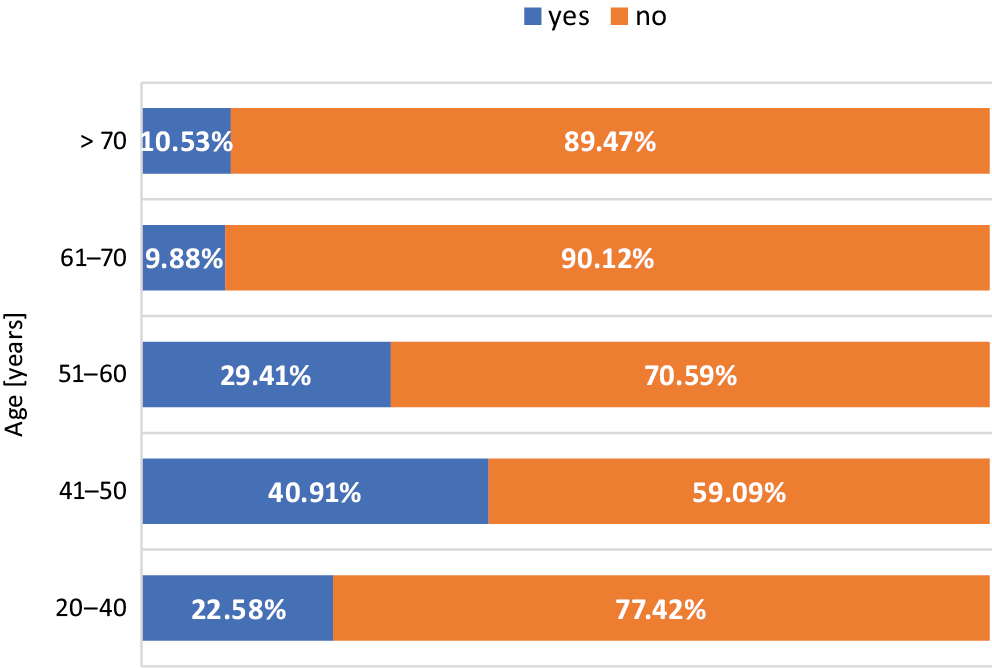

Regarding anchoring of dental implants in the mouth, 60.4% of participants responded “in the jawbone,” 14.7% thought it is placed “in the gum,” and almost 1/4 (24.9%) did not know the answer. There was a significant difference between men and women (p ≤ 0.001) in favor of women. Only 17.8% of respondents correctly answered both questions, indicating a basic knowledge of implants. The chi-squared test indicated a significant relationship between participants’ knowledge about dental implants and education level (p = 0.002; V = 0.240) (Figure 1), with results being in favor of higher education. Participant age affected knowledge (p = 0.002, V = 0.276) (Figure 2), as most correct answers were presented in the 41–50 group and showed a downward trend to the lowest score in those over 70. However, the effect size was considered small for both. There were no significant differences between men and women (p = 0.727) (Table 3).

Out of the 170 participants who were aware of dental implants, almost half (48.2%) indicated that implants require a similar hygiene routine as natural teeth, 15.3% thought that implants need less care, and 11.8% thought more care would be needed. However, 24.7% of respondents had no idea about how to take care of implants.

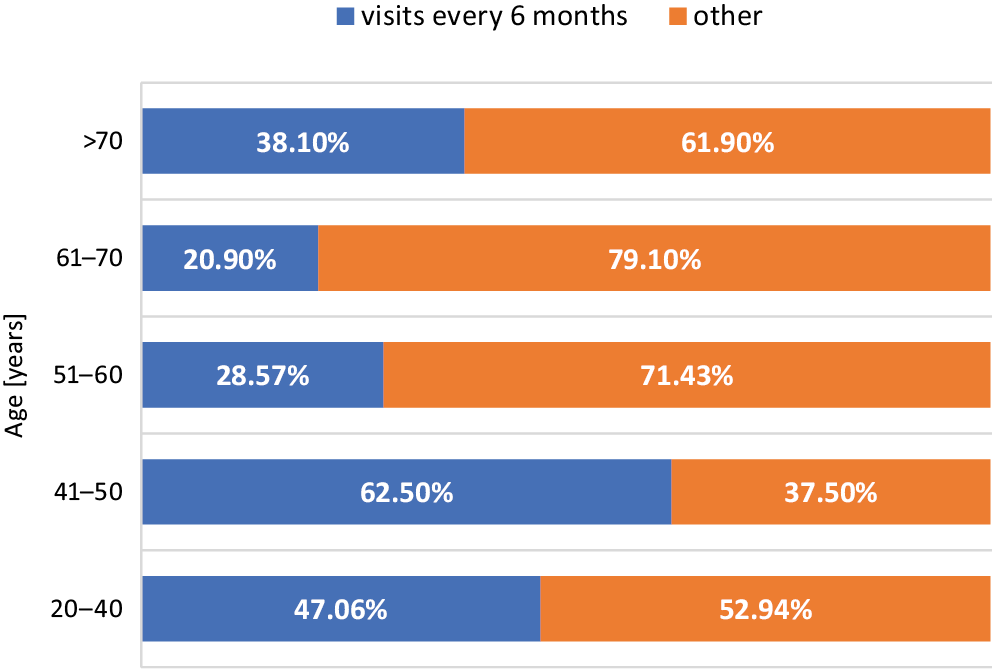

Regarding the follow-up visit frequency, only 32.4% of participants thought a dental check-up is needed every 6 months, including 31.3% in the female group and 35.1% in the male group (Figure 3). The difference between genders was not significant (p = 0.669). Few patients (17%) would visit the dentist once a year, while 5.9% saw no need to have a check-up, and most respondents (44.7%) had “no idea” how often they should attend. Nevertheless, the χ2 test indicated a significant relationship between participant age and knowledge of the frequency of follow-up appointments (p = 0.011; V = 0.277), with results shown in Table 4. There was no correlation between the level of education (secondary and higher) and knowledge (p = 0.180).

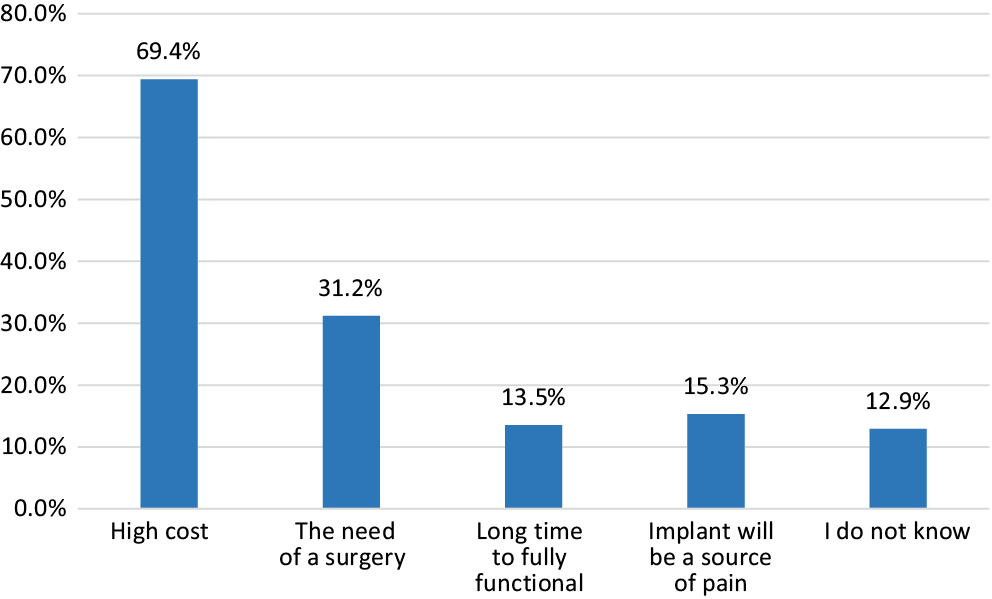

To assess patients’ major concerns regarding implant treatment, we asked a multiple-choice question. The 2 issues stated by the participants were high cost (69.4%) and the need for surgery (31.2%), with 15.3% of respondents replying: “I’m afraid the implant will be a source of pain,” 13.5% stating: “It takes time to complete the treatment and have a fully functional implant,” and 12.9% (22 out of 170) replying: “I do not know” (Figure 4).

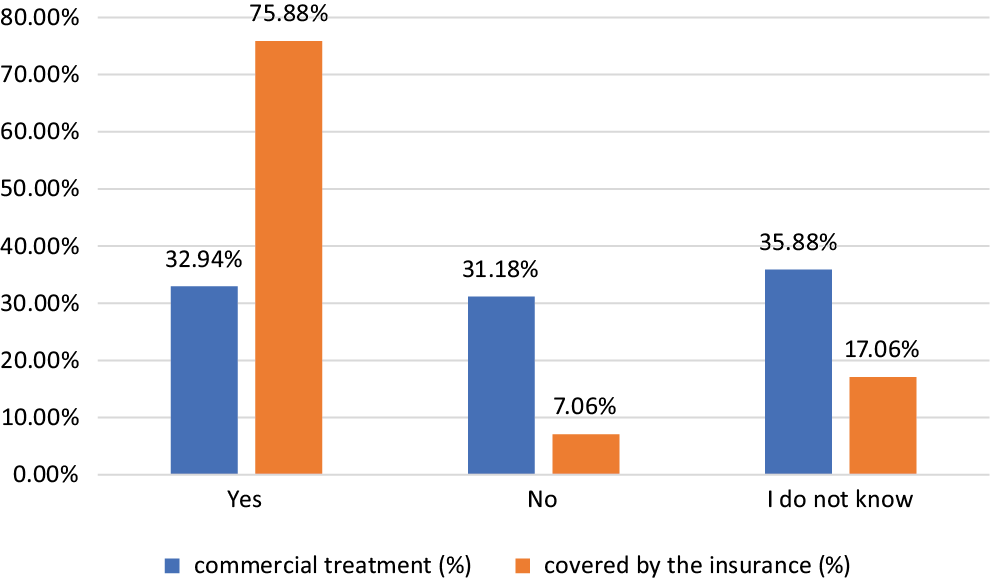

Patient willingness to undertake an implant treatment depending on the source of financing is shown in Figure 5. Regarding commercial treatment, 32.9% would like to have the implant if offered, 31.2% rejected it, and 35.9% did not know. However, when we asked if they would undergo treatment if the procedure was covered by the insurance, 75.9% answered affirmatively, only 7.1% rejected it, and 17% did not know. The χ2 test indicated a strong relationship between the respondent’s willingness and the source of treatment financing (p < 0.005). There were insignificant differences between men and women in commercial (p = 0.703) and insurance-covered treatment (p = 0.447). We did not find a relationship between the education level (secondary and high) and willingness for commercial (p = 0.143) or insurance-covered treatment (p = 0.111).

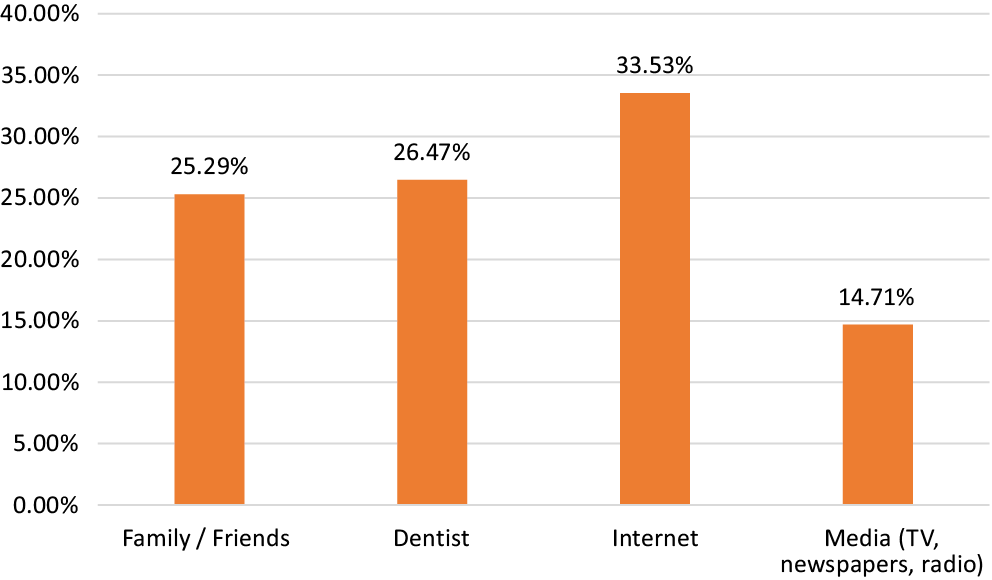

Sources of information

Regarding the question on the source of information about dental implants, 1/3 of the respondents (33.5%) indicated the Internet. The 2nd common source was a dentist (26.5%), followed by family/friends (25.3%), and the media (television, newspapers, and radio) (14.7%) (Figure 6).

Discussion

Today, dental implants are receiving widespread attention from professionals and patients due to their many advantages over traditional prosthetic restorations.16 Using implants to treat partial and complete edentulous patients brings many benefits through improving biting force, preventing alveolar bone loss, enhancing phonetics, better esthetics, and high treatment rate success.3, 17 Indeed, implant-supported prostheses provide better masticatory efficiency, retention, and higher comfort of use compared to conventional dentures.3, 15, 16 Moreover, a recent study among elderly people in Japan indicated an association between reduced chewing ability and impaired cognitive processes.18 Therefore, it could be stated that implant-based restorations not only significantly improve oral functions but also broadly defined quality of life.

Appropriate patient knowledge of implants is crucial for avoiding negative perceptions of the procedure and treatment process that could arise due to a lack of reliable information.3, 19 This study showed that 75.1% of respondents had heard about dental implants, which is similar to results from other countries, where the implant awareness rate was 77% in the USA,20 72–79% in Austria,21, 22 70.1% in Switzerland,13 and 70.7% in Norway.23 The study group demonstrated an unsatisfactory level of dental implant knowledge, meaning the research hypothesis was accepted. The outcome could be related to the low socioeconomic background of the group, as most respondents (61%) were above the age of 60 and without a higher education status (71%). As shown in the results, only 40 participants (18%) knew that the implant is a screw that replaces the tooth root and is anchored in a jawbone. We also found that 40% of patients considered dental implants as a whole, the screw and a crown. Therefore, clear communication between dental professionals and patients is crucial to avoid misunderstanding and confusion during treatment planning and financing.

Figure 1 demonstrates that the number of correct answers increased with increasing education levels. Regarding patient age, most correct answers were given by the 41–50 group and decreased with increasing age. This finding may be due to the greater awareness in this age group of their dental needs, as they are at the peak of their professional activity, are more interested in various treatment options, and are willing to seek information on this subject. These findings agree with other studies indicating that people with a higher degree, aged over 50, and living in urban areas had better implant knowledge.15, 24 However, it is worth considering that in this study the patients were randomly selected in the Department of Prosthetic Dentistry. Thus, the results could be different among patients who received implants in the past. Indeed, studies focused on comparing patients’ perception of implants to their experience with such treatment indicated that people with implant treatment history were better informed and more willing to undergo another procedure in the future.16, 19, 25, 26 On the other hand, dental implants were described as “scary,” “expensive,” and “painful” by patients who have never had one.19

Of the respondents, almost 45% stated that they do not know how often they should have a dental check-up, and around 6% thought that there is no need for further dental appointments after implant treatment. This could be explained by findings in other studies, which reported patients’ problem-oriented check-up behavior and pain as a common reason for visiting the dentist.27, 28 In contradiction to our findings of insignificant differences between genders, some studies29, 30, 31 indicated that women visit the dentist more frequently than men and show greater awareness of oral health.

Our survey showed that the primary source of information about implants was the Internet (33.5%), followed by the dentist (26.5%), relatives or friends (25.3%). It is reported that wide Internet access encourages patients to seek online health information,11, 32 even among those aged over 75,33 which is consistent with our findings. In contradiction to our study, different results were shown in other countries, with family and friends as a primary source of information and dental professionals a secondary source in Switzerland (52.3% friends and 40% dentist),13 Saudi Arabia (45.5% friends and 36% dentist),34 Nepal (30.2% friends and 17.7% dentist),12 and Sudan (38.2% friends and 35.7% dentist).35 Conversely, studies in Austria,21 India,36 and China,37 indicate dentists as a main source of knowledge (68%, 54.6%, and 42%, respectively). Thus, dental professionals should demonstrate adequate knowledge of implantology and be aware of the importance of their role as patient educators.

In this study, most patients stated the high cost (69.4%) of implant therapy as their main concern, followed by anxiety about the need for a surgical procedure (31.2%). Comparable results were reported in similar studies from other countries.12, 19, 38, 39, 40 Due to a significant number of elderly people participating in this study, the results of Müller et al. are noteworthy.13 It was stated that objections to implants of geriatric respondents were the expense of the procedure, the perception that undergoing such dental treatment was meaningless, and that they were too old.

Limitations

The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations. The 1st is the limited access to patients with various socioeconomic status because the study was conducted in the Faculty of Dentistry at Wroclaw Medical University. To reach Polish patients with different socioeconomic backgrounds, the survey should be conducted in many dental offices in other cities and small towns. More diversified sample testing would better reflect the general population, which leads to the second limitation, i.e., the insufficient sample size. The group of patients with primary education levels with awareness of dental implants was too small to run a statistical test and be considered representative of the population. Thus, we could not identify a relationship regarding patients’ education level. To overcome this limitation, the study should be carried out over a longer period of time and on a larger sample.

Conclusions

This study showed that patients were not adequately informed about implants, and variables such as age, education level, and gender influenced their awareness. As the Internet becomes a prevalent source of health information, dental professionals must provide sufficient information to patients to fill gaps and correct their knowledge on implant treatment. Misunderstandings about the treatment and its costs could be due to the terminological gap between the dentist and the patient. Since most patients fear the expense of implant treatment, measures should be taken to reduce the cost of the procedure to increase its availability.