Abstract

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 2 anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies, aducanumab (June 7, 2021) and lecanemab (July 6, 2023), for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, and will most likely also approve a 3rd one, donanemab, soon. While these antibodies have been shown to significantly reduce amyloid in the brain, there is little, if any, evidence that they provide clinically meaningful benefit for AD patients by slowing cognitive decline. I have said it before, and I say it again: the reported benefits of anti-amyloid antibodies observed in clinical trials are erroneous and based on misinterpretation of data and a trivial miscalculation. For example, Sims et al. (2023) reported in a phase III clinical trial that donanemab treatment of early symptomatic AD patients with amyloid and tau pathology provided 35% and 36% slowing of clinical progression and cognitive decline, respectively, as measured using the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (iADRS) and Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) psychometric tests. Here, in this editorial, I show that 2.5% and 9.6% would be better estimates for less cognitive impairment with donanemab treatment.

Keywords: clinical trial, Alzheimer, amyloid, donanemab

Introduction

The hypothesis that amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides and amyloid formation in the brain drive the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is stronger than ever and back in the spotlight of AD research and clinical trials, as exemplified by the recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies, aducanumab and lecanemab, for the treatment of patients with AD.1, 2, 3 However, these “transformative treatments that redefine AD therapeutics,”4 as Jeff Cummings put it, are not supported by any experimental evidence to show that anti-Aβ antibodies slow AD progression and reduce cognitive decline. While they do reduce amyloid in the brain, they can also cause serious health problems due to brain bleeding and swelling.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

What could be the reason for this apparent resurrection of the amyloid hypothesis? For one thing, it cannot be the reported benefits of aducanumab or lecanemab observed in clinical trials.10, 11 For example, as I have argued previously, the clinical benefit of lecanemab treatment is 9.6% less cognitive decline compared to placebo, while the claimed 27% benefit is based on misinterpretation of data and a trivial miscalculation.1, 2 Another example of misinterpretation of AD anti-amyloid therapy data, the topic of this editorial, is provided by the clinical trial of donanemab.3, 12

Donanemab

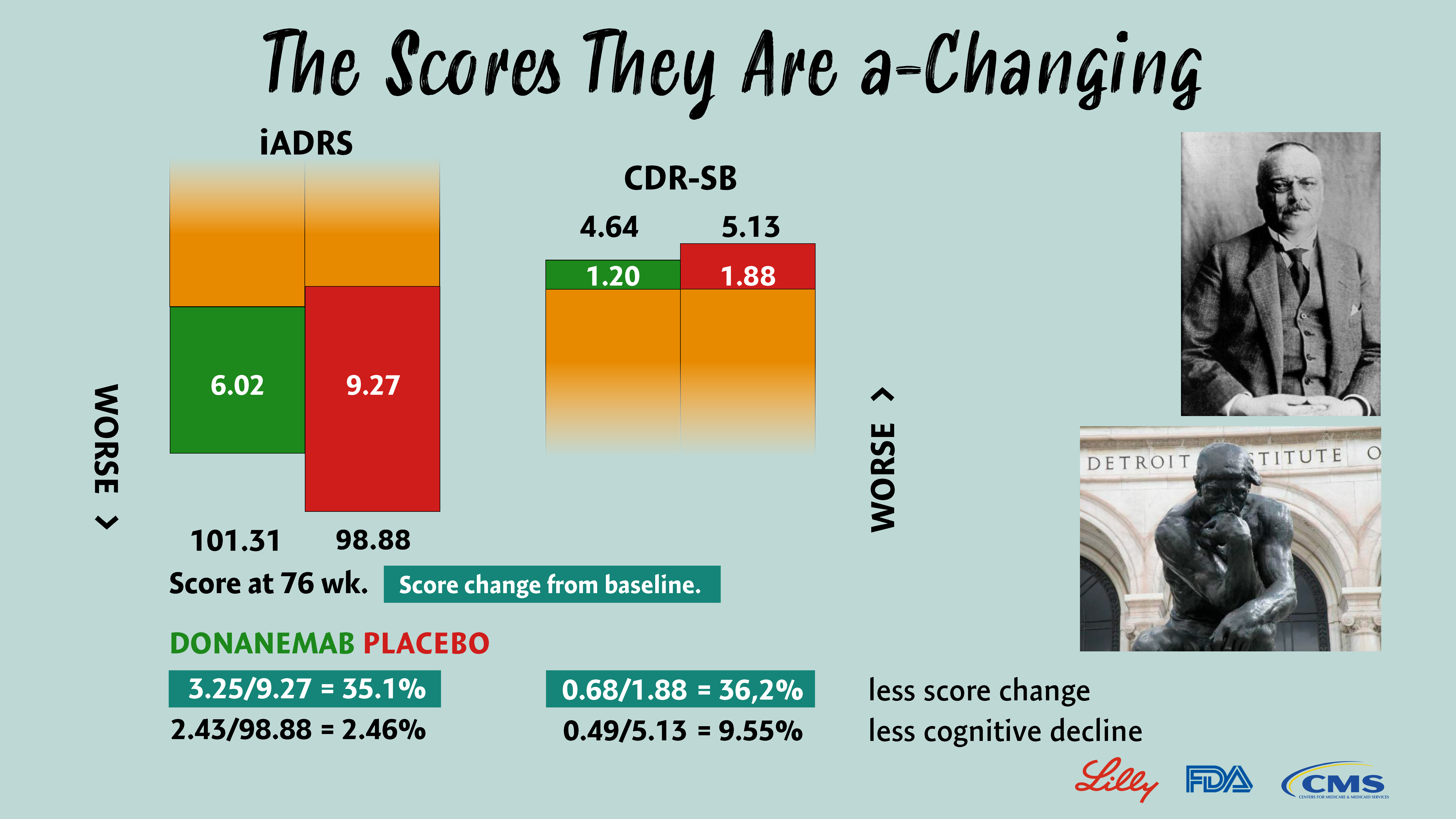

Donanemab is an anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody that binds to pyroglutamate-modified Aβ peptide found only in amyloid plaques.13 Sims et al. (2023) reported that donanemab slowed disease progression by 35.1% compared to placebo in a phase III clinical trial of 1736 participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.3 The findings were estimated using the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (iADRS), which measures cognition and function on a 144-point scale, with lower scores indicating worse performance. Here, from baseline to 76 weeks, iADRS score change was −6.02 in the donanemab group and −9.27 in the placebo group, a difference of 3.25, which the authors interpreted as a 35.1% (3.25/9.27) slowing of cognitive decline, or clinical progression, as the authors called it.3 This is a mistake. A score of 9.27 is not a score of cognition (the ‘amount’ of cognition) in the placebo group but is a change in cognition score calculated from the iADRS scores at baseline and 76 weeks. In other words, the 35.1% calculation disregarded the final iADRS scores at the conclusion of the 76-week trial to the effect that they would be irrelevant to cognition.

Obviously, it is not the score change but the final score that matters in cognition, which was 101.31 in the donanemab group and 98.88 in the placebo group.3 These are the scores that must be used when calculating the effect of donanemab treatment on cognition. Accordingly, I suggest the 101.31 − 98.88 = 2.43 difference, or 2.46% (2.43/98.88), is a better estimate for less AD progression and cognitive impairment with donanemab compared to placebo. Even in a trial as large as 1736 study participants, 2.46% is not a statistically significant difference. I also suggest, lest we forget, that the people living with AD, their family members and friends have the final say on donanemab, whether it provides 35% or 2.5% slower clinical progression. These numbers are different enough to make a difference. Subjective, yes, but that is what matters most in real life.14, 15

Sims et al. (2023) also measured donanemab’s clinical benefit using other psychometric tests, such as the Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), an 18-point scale, with higher scores indicating worse performance. They reported that donanemab slowed disease progression by 36%. Here, the CDR-SB score change from baseline to 76 weeks was 1.20 in the donanemab group and 1.88 in the placebo group, a difference of −0.68, or 36% (0.68/1.88) of slowing. Similar to the 35.1% benefit on iADRS, 36% is erroneous and due to a misunderstanding of the difference between cognition and change in cognition when calculating the clinical benefit of donanemab. The final score at the study conclusion was 4.64 with donanemab and 5.13 with placebo, so I suggest the 5.13 − 4.64 = 0.49 difference, or 9.55% (0.49/5.13), is a better estimate for less AD progression and cognitive impairment with donanemab compared to placebo.

Conclusions

Answers come and go, but the question remains: If amyloid drives AD, why have anti-amyloid therapies not yet slowed cognitive decline?16 But if amyloid does not drive AD, what is the question then? Therefore, in the spirit of “prevention is the only cure,” we have to do much more research on preventive therapies and increase public awareness of the role of healthy lifestyles in delaying the onset of AD. It’s about time. It’s about the human mind.17, 18, 19