Abstract

The cell membrane can be permeabilized when subjected to calibrated short electric pulses. This membrane alteration can be reversible, leaving cell viability unaffected. This set of events is called electroporation (EP). It is now used in clinical applications to introduce hydrophilic drugs into the cytoplasm. One of the EP applications is electrochemotherapy (ECT), in which EP is used for the selective delivery of drugs administered to treat cancer. The combination of EP with chemotherapy allows local cancer treatment, lowering the drug dose and reducing the side effects of systemic chemotherapy. Nowadays, bleomycin-based ECT (BLM-ECT) is a safe treatment for cutaneous tumors and skin metastases with established standard operating procedures. Additionally, there is emerging evidence that BLM-ECT may be particularly effective in combination with immunotherapies, acting synergistically and producing enhanced systemic anti-tumor effects. Still, to make it the first-choice therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma, further studies are needed to establish the relative effectiveness of ECT. Analyzing the EP phenomenon and the objective complexity of the associated effects at the cell level, we came across a problem that has not yet been investigated in increasing the therapeutic effectiveness of ECT. The profile and kinetics of extracellular vesicles (EVs) released from cells subjected to EP have not been analyzed. The exact nature of these EVs is unknown.

Key words: melanoma, electroporation, electrochemotherapy, extracellular vesicles

Introduction

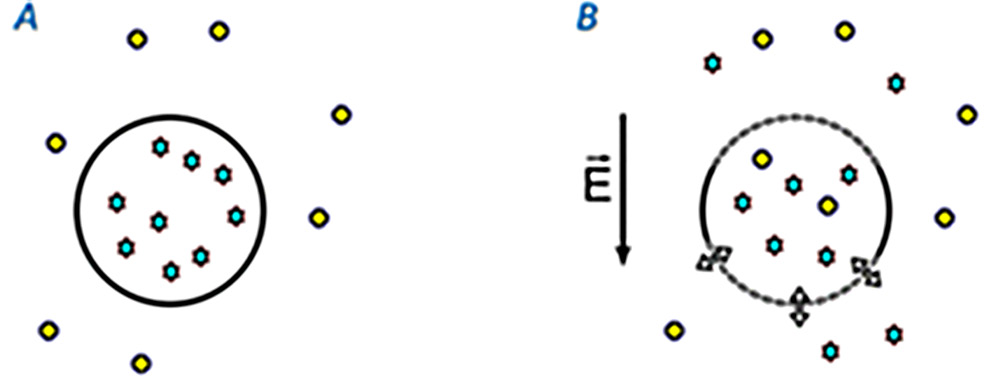

The cell membrane is a natural barrier that determines the control of the transport of molecules to the cell. Its permeability is an essential factor determining the effectiveness of therapy. Under the influence of a strong electric field, the lipid molecules in the cell membrane change their organization, and electroporation (EP) occurs. Transient hydrophilic pores are formed, constituting an additional pathway of transport of macromolecules through the cell membrane (Figure 1).

Currently, EP is used as a standard in in vitro cell culture as the purest available gene transfection method.1 Electroporation can also be used in gene therapy and in vivo immunogenotherapy. One of the EP applications is electrochemotherapy (ECT), in which EP is used for the selective delivery of drugs administered to treat cancer. The combination of EP with chemotherapy (CT) significantly reduces the need for surgical intervention, allows local treatment of cancer, lowers the drug dose, and reduces the side effects of systemic chemotherapy.2 Effectiveness of this method is also increased due to the occurrence of the so-called vascular lock after applying an electrical pulse. It reduces the blood flow through the tumor and therefore causes a more extended stay of the drug in the tumor cells. In addition, the blood vessels are damaged, resulting in decreased blood flow within the tumor and the activation of the immune system.3

When bleomycin was used with EP, its cytotoxicity index increased 1000 times.4 The first clinical tests on using ECT were carried out in the 1990s. The squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck were treated with intravenous injection of bleomycin, followed by EP of the nodules.5 The investigators found a significant reduction in the size of neoplastic lesions after treatment. In 2006, the European Standard for Operating Procedures for ECT and Electrogene Therapy (ESOPE) was developed to define standard operating procedures.6 Several methods of treatment have been proposed to ensure the patient’s safety and obtain optimal treatment results concerning the selection of a chemotherapeutic drug, the way of drug delivery (intravenous or intratumoral), and the shape of the electrode (plate or needle) and EP parameters.7 Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin or cisplatin of malignant melanoma tumors results in a marked reduction of tumor size. No local or general adverse effects are observed during treatment – only temporary redness and accumulation of serum in the treated areas.6 Electrochemotherapy is used today in clinical practice to treat cutaneous and subcutaneous tumors, especially melanoma tumors.8, 9 The procedure is applicable all over the body surface, with high response rates across various tumor subtypes. In addition, the treatment can be performed with local anesthesia if a patient has a few smaller lesions.10 New electrodes have been developed to access deep-seated and surgically challenging tumors in different ways.11

The effectiveness of systemic and adjuvant therapies has significantly progressed recently. However, more effective therapeutic options for the treatment of melanoma are still being sought. Bleomycin-based ECT (BLM-ECT) is currently considered a safe and effective form of treatment of skin tumors and their metastases. This method has been included in international clinical guidelines. The European Society for Medical Oncology recommendations on managing locoregional melanoma12 cited the study by Kunte et al. That recently published cohort study found that 78% (306 patients) had a complete or partial response and 58% (229 patients) presented a complete response to BLM-ECT.13 Currently, clinicians most often choose BLM-ECT treatment for palliative therapy. However, due to the proven effectiveness of BLM-ECT, it can be considered the method of choice when surgical resection or radiotherapy are contraindicated. Moreover, BLM-ECT can be performed after other forms of treatment and can be repeated in the same area several times.14 Mozzillo et al. presented a report on the retrospective investigation of 15 patients treated with ipilimumab who also received ECT. Over the study duration, a local objective response was attained in 67% of patients. In addition, a systemic response was observed in 9 patients, resulting in a disease control rate of 60%. Evaluation of circulating T-regulatory cells showed significant contrasts between responders and non-responders. The above study showed that the combination of ipilimumab and ECT benefits patients with advanced melanoma, warranting other investigations and trials.15 An essential method of treating melanoma with in-transit metastases is systemic therapy, while ECT may be a treatment option for patients who cannot receive therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors. However, the treatment method should be carefully balanced so as not to deprive the patient of the chance of long-term survival.16 Decisions about systemic and adjuvant therapy for melanoma patients should be made on an individual basis, taking into consideration potential toxicities, costs and patient preference. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-compliant systematic review analysis suggested that patients with metastatic melanoma should be treated by multidisciplinary teams including oncologists, dermatologists and radiation oncologists.17 In addition, ECT procedures should be performed in centers with appropriate equipment and trained personnel experienced in this method.

Evidence indicates that simultaneous local and systemic therapy modalities may lead to synergistic anti-tumor effects in melanoma. Increased response and overall survival when using ECT combined with immunotherapy have already been noted.10 Heppt et al. showed the use of ECT combined with a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T cell antigen-4 (ipilimumab) or PD-1 (programmed death receptor 1) inhibitor. Thirty-three patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma participated in the study. Twenty-eight patients received ipilimumab, while 5 were treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. It was observed that ipilimumab combined with ECT was tolerable and showed a high systemic response rate.18 Also, Campana et al. investigated the effectiveness of ECT in combination with a PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab). They compared patient outcomes after treatments with pembrolizumab, pembrolizumab with ECT, and ECT alone. The combined application of inhibitor and ECT was safe and more effective in preventing further tumor growth than pembrolizumab alone. In addition, the patients treated with pembrolizumab and ECT shared lower disease progression and more prolonged survival than those who received only pembrolizumab. The above study showed that ECT might increase the effect of pembrolizumab when an in situ vaccination against melanoma cells is performed.19

An interesting approach to the treatment of metastatic melanoma with EP was presented by Greaney et al.20 Systemic interleukin (IL)-12 is connected with life-threatening toxicity, but intratumoral delivery of IL-12 via telseplasmid (tavo) electroporation is safe and can induce tumor regression in remote places. The mechanism of these reactions is unknown but is supposed to result from a cellular immune response. Greaney et al. results indicated that this local treatment could induce a systemic T-cell response.20

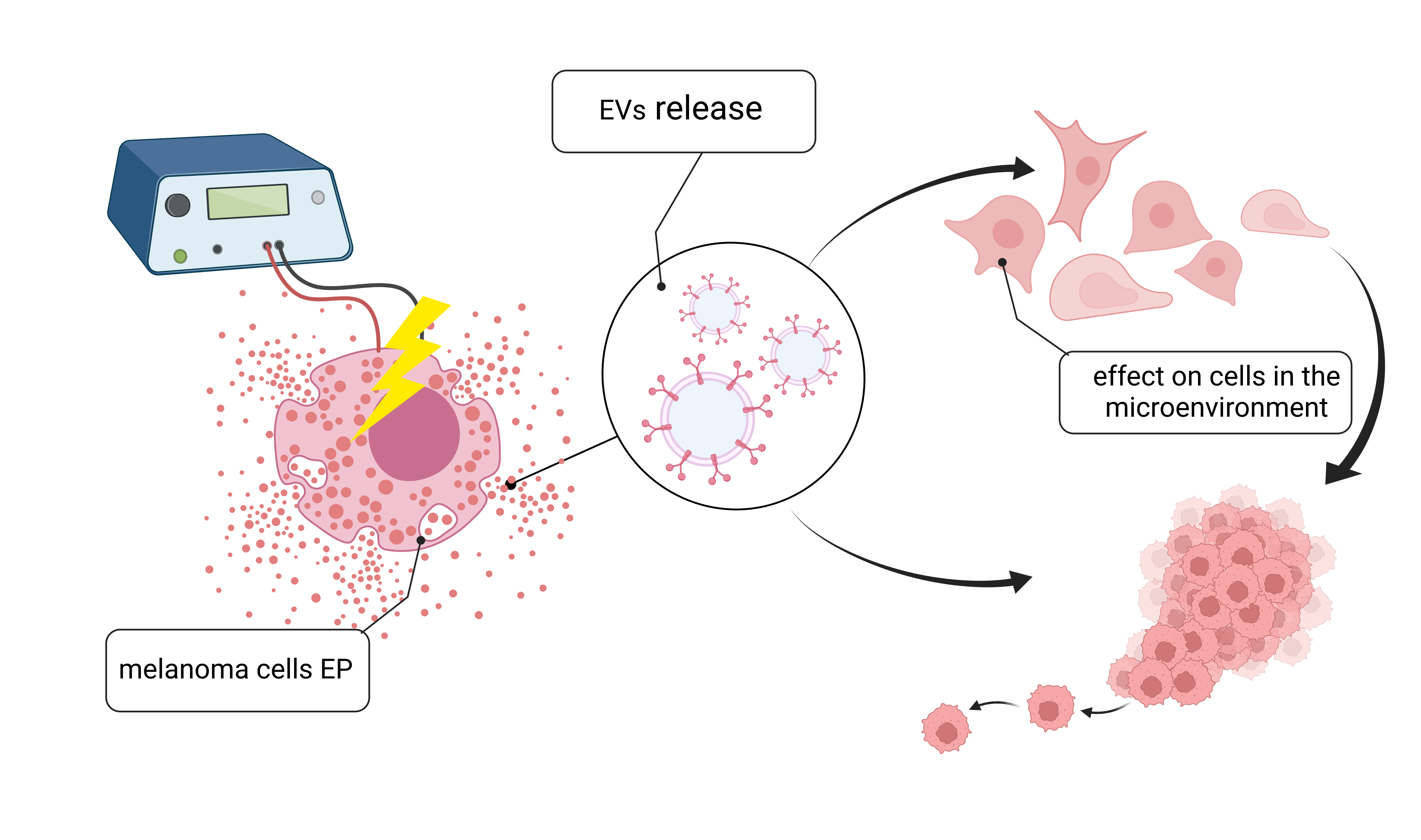

Analyzing the EP phenomenon and the objective complexity of the associated effects at the cell level, we came across a problem that has not yet been investigated in the context of increasing the therapeutic effectiveness of ECT. The profile and kinetics of extracellular vesicles (EVs) released from cells subjected to electroporation have not been investigated. The exact nature of these EVs is unknown. It is also not clear how the profile of the released EVs depends on the pulse duration.

Electroporation of melanoma cells: What about molecules transported outside the cell?

Until recently, it was believed that the role of EVs was to remove unnecessary compounds outside the cell. However, we now know that they have enormous potential. They mediate intercellular communication, enable the transfer of bioactive molecules, and can transfer the charge to individual cells by acting on specific receptors in target cells under physiological and pathophysiological conditions.21 The main features of EVs depend on the cell they come from, their state and the requirements of the external environment. The EVs are currently a highly heterogeneous group and can be divided into 3 populations: exosomes, ectosomes and apoptotic bodies.

Both normal and cancer cells release all types of EVs. Since EVs modulate intercellular signaling, protein transport and cell proliferation, EVs of neoplastic origin can induce and stimulate cancer growth when delivered to recipient cells. Melanoma-derived exosomes have increased tumor cell proliferation and contribute to the epithelial–mesenchymal transition and pre-metastatic niche formation.22 They are also involved in extracellular matrix degradation and activation of integrin signaling. Melanoma-derived exosomes can modulate many immune system functions, counteracting the immune response against melanoma.23, 24 The receptor tyrosine kinase MET has also demonstrated its effect on bone marrow progenitor cells. In this way, it interferes with the differentiation and maturation of antigen-presenting cells, controlling the survival and apoptosis of the effector T cells, cytokine production, and NK cell cytotoxicity.25 Recent studies have found twice as many ectosomes released in vitro by melanoma cells as normal melanocytes. Melanoma-derived ectosomes show higher levels of tissue factor, which is responsible for the coagulation process associated with carcinogenesis.26 They can also induce metastasis by transporting metastases or their endogenous activators.27 It has also been shown that ectosomes can transform fibroblasts into fibroblasts related to cancer and suppress the immune response by EV-associated Fas ligand.28

Peinado et al. identified MET-associated signaling proteins transmitted by exosomes derived from highly metastatic melanoma cells. They mediate provasculogenic effects on bone marrow progenitor cells.29 MET oncogene causes neoplastic transformation and stimulation of neoplastic cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis.30 It has been shown that the co-expression of TYRP2 and MET in exosomes is associated with melanoma progression. Moreover, Peinado et al. showed that the transfer of exosome-derived MET oncoproteins to bone marrow progenitor cells promotes metastasis in vivo.29

Our preliminary studies on the A375 human melanoma cell line electroporated using a low-intensity electric field (unpublished data) showed a clear difference in kinetics of calcein released from cells depending on the parameters of reversible EP. The analysis of cell confluence levels measured in parallel with the level of calcein released from cells showed no significant changes, confirming that the EP parameters used did not affect cell viability. It was also observed that a low-intensity electric field causes marked differences in the amount of EVs released from A375 melanoma cells as a function of EP parameters 24 h after its application. According to our studies, various parameters of reversible EP impact the kinetics and profile of released EVs following the application of reversible EP with varying parameters. Different EP parameters will probably affect the protein profile of EVs released after EP. The above proteins may significantly influence the cells in their environment and influence the process of metastasis.

Conclusions

Currently used ECT protocols for malignant melanoma are based on parameters established by ESOPE, where the process conditions did not consider the extracellular transport following EP. More studies analyzing transport from the cell to the external environment induced by external electromagnetic fields of varying intensity are needed to optimize the therapeutic process using ECT.