Abstract

Background. Circular RNA homeodomain interacting protein kinase 3 (circHIPK3) has been implicated in facilitating angiogenesis in various conditions. However, its role in steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) remains unclear.

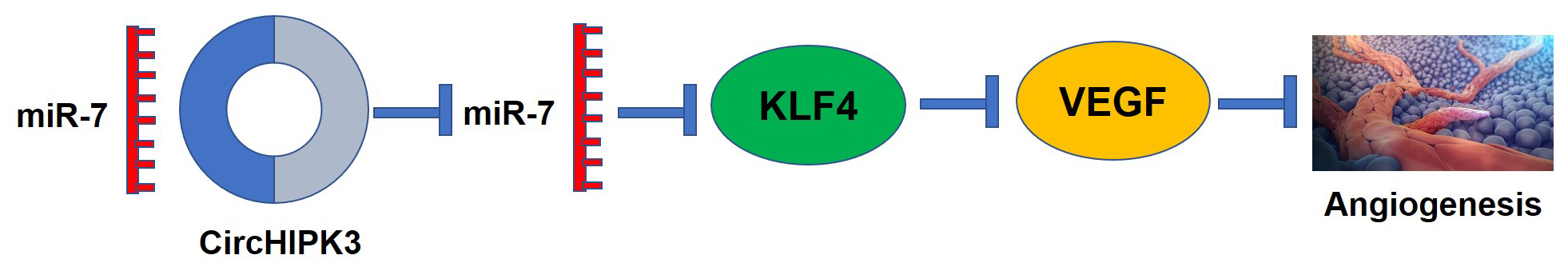

Objectives. To investigate whether circHIPK3 promotes bone microvascular activity and angiogenesis by targeting miR-7 and Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in ONFH.

Materials and methods. Fifty patients with steroid-induced ONFH undergoing hip-preserving surgery or total hip arthroplasty were included in this study. The expression of circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4 was evaluated using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in necrotic and healthy samples of the femoral head. Bone microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) were extracted and cultured with 0.1 mg/mL hydrocortisone to create a hormonally deficient cell model. These BMECs were then transfected with either circHIPK3 overexpressing or silencing plasmids with or without miR-7 mimics. The MTT assays were used to detect cell proliferation. Scratch assays were used to assess the migration ability of the BMECs. The tube formation was carried out using an in vitro Matrigel angiogenesis assay. Annexin V-FITC/PI and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays were used to assess the degree of apoptosis. Western blot assays were carried out to discern KLF4 and VEGF expression. The interactions of circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4 were confirmed using luciferase, RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP), RNA pull-down, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays.

Results. The circHIPK3 and KLF4 expression was decreased, whereas miR-7 expression was increased in necrotic tissues compared to non-necrotic samples. Both circHIPK3 and KLF4 expression correlated negatively with miR-7. The overexpression of circHIPK3 promoted the proliferative, migratory and angiogenic capabilities of the BMECs, while adding an miR-7 mimic reversed these effects. At the same time, the overexpression of circHIPK3 reduced the apoptosis rate of the BMECs and increased KLF4 and VEGF protein expression, but adding an miR-7 mimic reversed these effects. The FISH, RNA pull-down, RIP, and luciferase assays revealed an interaction between circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4.

Conclusions. The circHIPK3 promotes BMEC proliferation, migration and angiogenesis by targeting miR-7 and KLF4/VEGF signaling.

Key words: miR-7, circHIPK3, bone microvascular endothelial cell, osteonecrosis of the femoral head

Background

The hallmark of osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is progressive bone cell and bone marrow necrosis, which leads to femoral head necrosis if left untreated.1 It accounts for approx. 10% of the 250,000 total hip arthroplasties (THAs) performed in the USA each year.2, 3 Osteonecrosis of the femoral head can be either traumatic or nontraumatic. Primary nontraumatic ONFH accounts for 30–50% of all ONFH cases in adults aged 30–60 years in China; it is linked to steroid use.4 Although clinical steroid use remains closely associated with ONFH progression, the exact mechanism is not clear. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head involves a disruption in bone vascular supply, which is related to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, and coagulopathy.5, 6, 7, 8 Endothelial cells are directly damaged by glucocorticoids, causing vasoconstriction, thrombosis, coagulopathy, and an abnormal fibrinolytic system, all of which culminate in ONFH.9, 10 Femoral head blood circulation needs to be maintained to prevent steroid-induced ONFH.

The current literature suggests that dysfunction of bone microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) caused by glucocorticoids may lead to altered femoral head microcirculation, so it is an important contributor to glucocorticoid-triggered ONFH.11 Bone microvascular endothelial cells are distributed in the vascular sinuses and inner bone layers, and play an important role in angiogenesis and vascular homeostasis.12 Moreover, BMECs regulate cellular apoptosis in relation to angiogenesis.13 Angiogenic function and vascular integrity have been reported to be inversely related to the levels of apoptosis.14 Continuous exposure to glucocorticoids results in angiogenesis inhibition, cell apoptosis stimulation and endothelial cell dysfunction.15 A recent study showed that the angiogenic activity of BMECs was decreased while its apoptotic activity was increased in patients with glucocorticoid-triggered ONFH.16

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are noncoding RNAs in the shape of a covalently closed loop spliced together by covalent bonds at the 3’ and 5’ ends, which increases their stability, enabling them to resist digestion by RNA exonuclease enzymes.17 This is in contrast to linear RNA, which has different 5’ and 3’ ends that mark the stop and start transcription sites. The circRNAs are associated with a variety of disorders, including musculoskeletal,18 gastrointestinal19 and cardiovascular diseases,20 as well as several malignancies.21 Circular RNA homeodomain interacting protein kinase 3 (circHIPK3) is a ubiquitous circRNA that absorbs microRNAs (miRNAs) in order to regulate cell angiogenesis, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis.22 The circHIPK3 also participates in many pathophysiological processes, including fibrosis, tumor formation and vascular endothelial damage.23 The miRNAs are an evolutionarily conserved class of small regulatory noncoding RNAs that have multiple biological functions.24 Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of circRNAs to sponge miRNAs in order to modulate gene expression.25 However, data regarding the sponge role of circRNA in the occurrence and progression of steroid-triggered ONFH are scarce, especially with regard to circHIPK3.

The Krüppel-like factors (KLFs) are DNA-bound zinc finger transcription families comprised of 9 specific proteins and 18 KLFs.26 Several members of the KLF family, such as KLF2, KLF4, KLF5, KLF6, KLF10, and KLF15, are strong angiogenesis promoters in various cellular environments.27, 28, 29, 30 Hale et al. found that KLF4 promotes the angiogenesis by regulating Notch signaling.31 Both in vitro and in vivo angiogeneses are promoted by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The KLF4 has been shown to activate VEGF signaling in order to promote angiogenesis in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells.32

Objectives

This study was performed to investigate whether circHIPK3 promotes BMEC activity and angiogenesis by targeting miR-7 and KLF4/VEGF signaling in ONFH.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

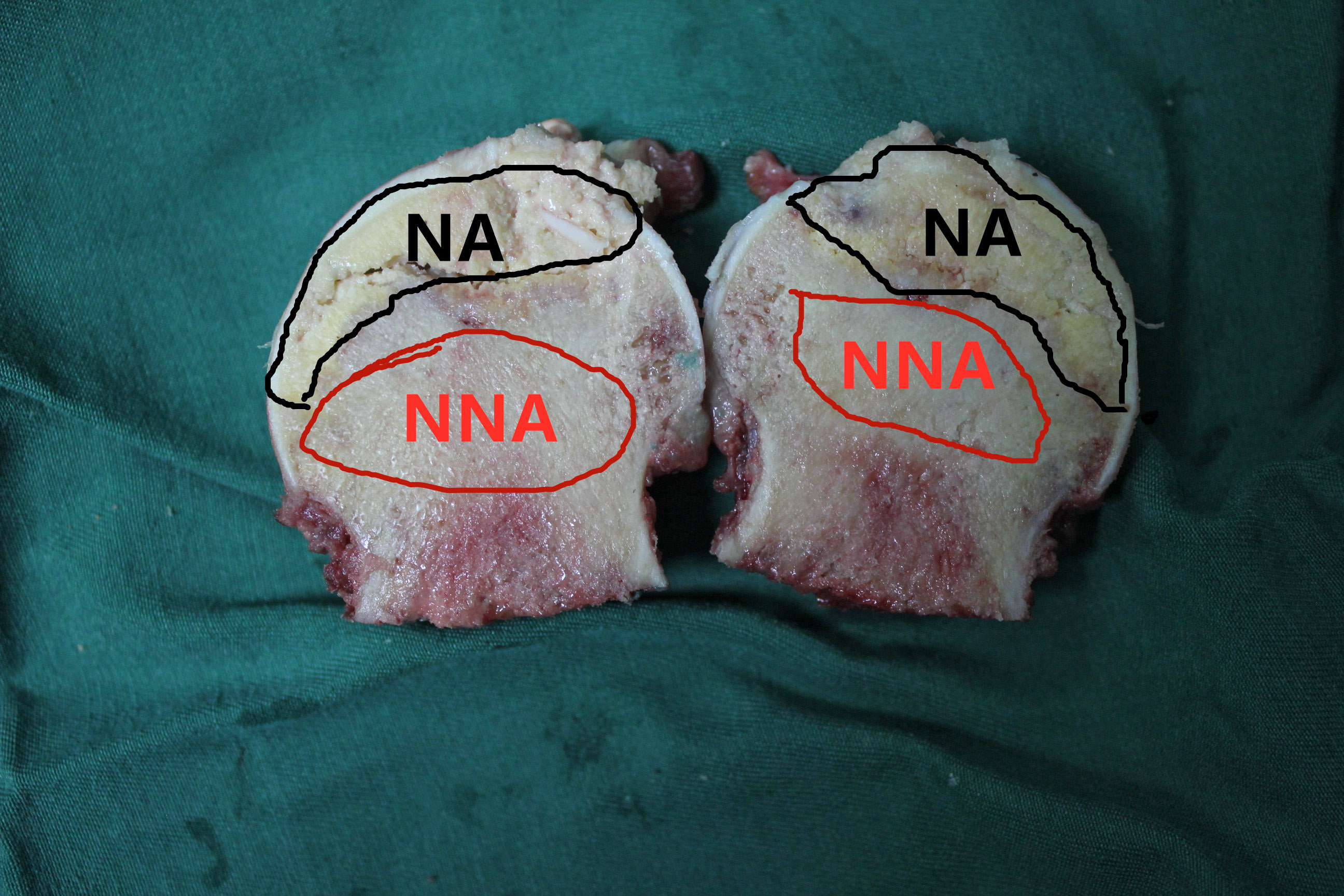

From April 2020 to April 2021, 50 steroid-induced nontraumatic ONFH patients (37 male, 13 female; mean age: 46.4 ±7.8 years) undergoing hip-preserving surgery or THA at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in Zhuhai Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, China, were recruited for this study. All patients were diagnosed using anteroposterior and lateral pelvic radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging. Steroid-induced ONFH was defined by a history of a highest daily dose of 80 mg or a mean daily dose ≥16.6 mg of prednisolone equivalent within 1 year before the development of symptoms or radiological diagnosis in asymptomatic cases. The exclusion criteria were alcohol-induced ONFH, idiopathic ONFH, systemic comorbidities, and a clear history of trauma. The necrotic area of the femoral head was selected as the case group, and the adjacent non-necrotic area was regarded as the control group (Figure 1). The ethics committee of Zhuhai Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine approved the study (approval No. 20200022). All participants provided informed consent. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Tissue collection

Necrotic and healthy tissue collection was performed based on previous study by Jiang et al.33 In terms of preserving surgery, marrow core decompression followed by bone grafting was performed. After anesthesia, a longitudinal incision was made on the external side of the femur, 2 cm below the greater trochanter. The position of the guide pin was monitored using a C-arm X-ray machine (Ziehm-9; Ziehm Imaging, Nuremburg, Germany). The guide pin was inserted into the center of the necrotic area beneath the femoral head cartilage through the femoral neck from under the trochanter, and it was screwed into the edge of the lesion area below the head using a decompressor with a tube core. A biopsy device was screwed into the lesion area, and yellowish-white wax-like loose diseased tissue (necrotic tissue) was extracted from the front end of the biopsy device to be used for further study. Non-necrotic tissue as a control was collected at least 3 cm away from the margin of necrotic tissue using the biopsy device. For THA, the femoral head was obtained according to the standard surgical procedure, and necrotic samples and adjacent non-necrotic samples were collected directly (Figure 1).

Quantitative real-time polymerase

chain reaction

TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA) was used to extract total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA using the miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, USA). The SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) was used to aid the RT-qPCR, with the ABI StepOne Real-time Quantitative PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) used to carry out the analysis. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were as follows: 94°C for 40 min, 60°C for 35 min, 72°C for 30 s, and 90°C for 3 min, for a total of 45 cycles. The internal loading controls were U6 for miR-7 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for KLF4 and circHIPK3. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The primers used were as follows: KLF4 forward 5’-CCCACATGAAGCGACTTCCC-3’ and reverse 5’-CAGGTCCAGGAGATCGTTGAA-3’; miR-7 forward 5’-AAAAGAACACGTGGAAGGATAG-3’ and reverse 5’-CGCCTAACGTACCGCGAATTT-3’; circHIPK3 forward 5’-GGGTCGGCCAGTCATGTATC-3’ and reverse 5’-ACACAACTGCTTGGCTCTACT-3’; GAPDH forward 5’-TCACCAGGGCTGCTTTTAAC-3’ and reverse 5’-GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG-3’; U6 forward 5’-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3’ and reverse 5’-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3’.

Isolation and culture of BMECs

and the glucocorticoid damage model

The BMECs were cultured based on the previously published instructions.33 The subchondral area of the femoral head was used to extract the cancellous bone. Digestible bone fragments were treated with 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 0.2% type I collagenase for 5 min. The reaction was stopped by adding Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Waltham, USA). The lytic products were filtered using a 70-μmol/L cell filter and centrifuged for 6 min at 1500 rpm. The supernatant was removed, and the cell sediments were exposed to an endothelial cell medium (ECM) (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, USA) containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin, 5 mL recombinant human VEGF, and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) in 5% CO2 in a 37°C wet incubator. For cell passage, the medium was removed. The cells were washed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 5 min. The reaction was ceased using a medium with 10% FBS. The cells were then repeatedly blown using a 1-microliter pipette tip. Cell passage was performed when cell confluence achieved 90%, and the 3rd cell generation was used for the following procedures.

Plasmid and oligonucleotide transfection

A circHIPK3 overexpressing plasmid was created by synthesizing human circHIPK3 cDNA and inserting it into a luciferase-labeled pcDNA3.1 vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The BMECs were seeded in a 6-well plate and incubated with serum-free medium (Opti-MEM™; Gibco) at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere overnight. The overexpression (OE)-circHIPK3, circHIPK3 small interfering RNA (siRNA), miR-7 mimics, and negative controls (NC; GenePharma, Shanghai, China) were used for transfection with the Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) reagent as per manufacturer’s protocols.

Examination of cell proliferation

and viability

The proliferation of BMECs was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated in 96-well plates, followed by the addition of 10 μL of the CCK-8 solution and 100 μL of ECM into each well for a 2-hour incubation period. The absorbencies at each time point were measured at 450 nm using an iMark™ Microplate Absorbance Reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA).

Wound healing assay

In the wound healing test, 5×105 BMECs were seeded in a 6-well plate for 24 h until 90% cell confluence was achieved. A 10-microliter pipette tip was used to scratch the cell monolayer and draw a gap on the plates. The scratch width was measured at 0 h and 48 h, and the degree of cell migration was calculated as follows: migration area (%) = (A0 − An)/A0 × 100, where A0 represents the area of the initial wound and An represents the remaining area of the wound at the metering point.

Transwell assay

In the transwell assay (8 μm; Corning, New York, USA), the upper chamber was filled with 100 μL of serum-free medium and 5×105 BMECs from each treated group. The bottom chamber contained 500 μL of serum with ECM and FBS. The upper chamber was rinsed using PBS and incubated for 12 h at 37°C and in 5% CO2. The upper chamber cells were then picked up using a cotton swab. The bottom chamber was exposed to 20 min of 4% paraformaldehyde to fix the cells before the addition of 1% crystal violet for 30 min to stain any migratory cells. The cells were then observed under a light microscope (Leica DC 300F; Leica Camera AG, Wetzlar, Germany).

Tube formation assay

A 96-well plate coated with 100 μL BD Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA) was cured and polymerized for 1 h at 37°C. The transfected BMECs were pretreated with ECM containing FBS for 24 h. Then, 2×105 cells per well were seeded onto the Matrigel. After a 6-hour culture period, the tube formation process was visualized microscopically, followed by quantification using ImageJ v. 6.0 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA).

Annexin V-FITC and PI assay

First, BMEC apoptosis was detected using an Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After transfection, 500 μL of binding buffer was used to resuspend the BMECs. Then, 5 μL PI and 5 μL Annexin V-FITC were added to the suspended cells, followed by a 20-minute darkroom incubation period. The samples were washed on BD FACS™ Lyse Wash Assistant (BD FACSCanto™ II and BD FACSCanto™ 10-Color; BD Biosciences). Cytometry was used to assess the degree of cell apoptosis.

TUNEL assay

The rate of BMEC apoptosis was evaluated using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining with an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then washed with PBS. Next, 0.3% Triton-X 100 in PBS was added and incubated for 5 min. The cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS. Then, the cells were incubated with 50 μL TUNEL Dilution Buffer (Roche-11966006001; Roche) in a 37°C humidified chamber for 1 h. The nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min at room temperature in the dark and later mounted with an anti-fade mounting medium. A fluorescent microscope (Olympus CX23; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was used to capture images. Three independent investigators separately quantified the number of apoptotic cells based on the number of TUNEL-positive cells.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 12-well plates were used to house BMECs seeded onto glass coverslips. Phosphate-buffered saline was then used to rinse the cells before they were fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde. Phosphate-buffered saline containing 5 mM MgCl2 was then used to rinse the cells twice. The cells were then rehydrated for 10 min in 2× saline sodium citrate (SSC) and 50% formamide. A solution consisting of 0.5 ng/mL fluorescently labeled circHIPK3 and miR-7 probes, 2.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.25 mg/mL salmon sperm DNA, 2× SSC, 0.25 mg/mL Escherichia coli transfer RNA, and 50% formamide was mixed. The cells were incubated in the solution at 37°C. After 3 h, the cells were rinsed twice for 20 min with 2× SSC and 50% formamide at 37°C. Then, they were incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 solution at 4°C for 5 min. The penultimate detergent contained DAPI. The specimens were analyzed using a Zeiss confocal fluorescence microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany).

Luciferase reporter assay

Site-directed mutation was used to produce a circHIPK3 mutant. Similarly, by replacing the seed region of the miR-7 binding site, we produced a KLF4 mutant 3’UTR. The firefly luciferase-expressing vector pGL3 (Shanghai Gena Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to clone the mutant sequence. For luciferase activity detection, the BMECs were seeded in 24-well plates at 4×104 cells/well 24 h prior to transfection by using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were collected and lysed 48 h after transfection. The Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, USA) was used to assess luciferase activity. Luminescence levels were normalized against the β-lactamase gene of the pGL3 luciferase carrier.

RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation

RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) testing to identify the protein pre-mNRIP1 and the QKI protein was carried out using an RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation kit (17-700; Merck, Burlington, USA) in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The QKI-RNA mixture was then absorbed by the magnetic beads.

RNA pull-down assay

Ultrasound treatments were used on 1×107 lysed BMECs. The C-1 magnetic beads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) were incubated with circHIPK3 probes for 2 h at 25°C to produce a probe-coated magnetic bead. Cell lysates with circHIPK3 probes or oligo probes were incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with detergent, the bead-bound RNA mixture was eluted and extracted with reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) using the RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The miR-7 pull-down was performed following the same procedure.

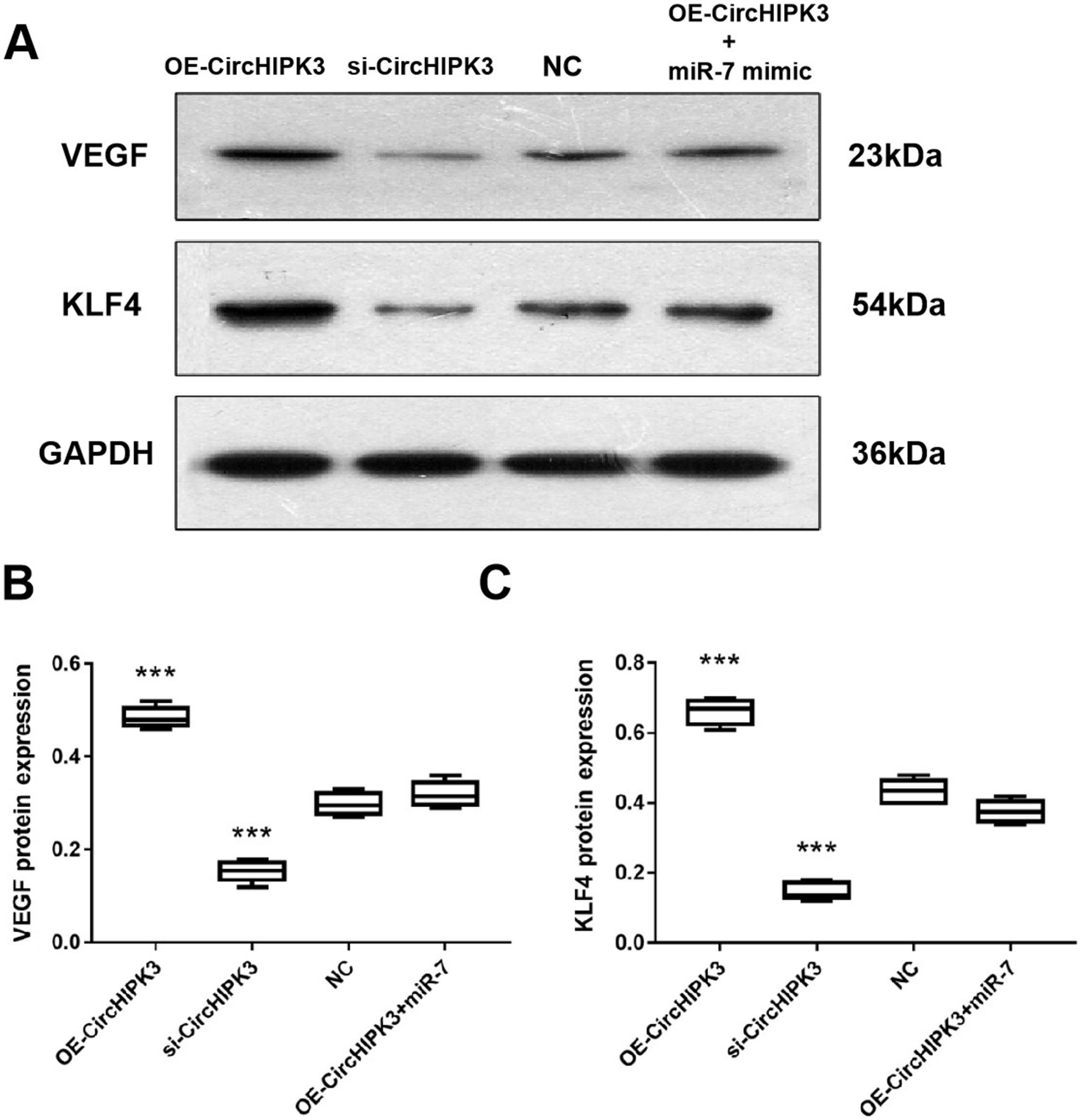

Western blot analysis

After transfecting the OE-circHIPK3 and si-circHIPK3 into the BMECs for 24 h, a RIPA lysis buffer (ab156034; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used to extract proteins for total protein concentration evaluation with a BCA Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein samples (40 μg) were separated on sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% w/v) and transferred electrophoretically to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The cell membranes were blocked with 5% dry skim milk and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-VEGF (1:1000; Abcam), KLF4 (1:1000; Abcam) and β-actin (1:3000; Abcam). The cell membranes were then incubated with their corresponding secondary antibodies. Electrochemiluminescence using Invitrogen reagent was used to analyze the strips. Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ v. 6.0 software.

Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism v. 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) was used for data analysis. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test was used to test the distribution (normal or non-normal) of the variables. The F-test was used to check the homogeneity of variances between groups. Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD) when the data distribution was normal. Otherwise, the values were expressed as median. When the data met normal distribution and homogeneity simultaneously, the Student’s t-test was conducted for comparisons between the 2 groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out when 3 or more groups were compared, followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis. When the data did not meet either normal distribution or homogeneity, the Mann–Whitney (M–W) U test was conducted for comparisons between the 2 groups. The Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) test was used when 3 or more groups were compared, followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis. The correlation between 2 genes was examined using the Spearman’s correlation test. A value of p < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. All the statistical results have been demonstrated in Table 1.

Results

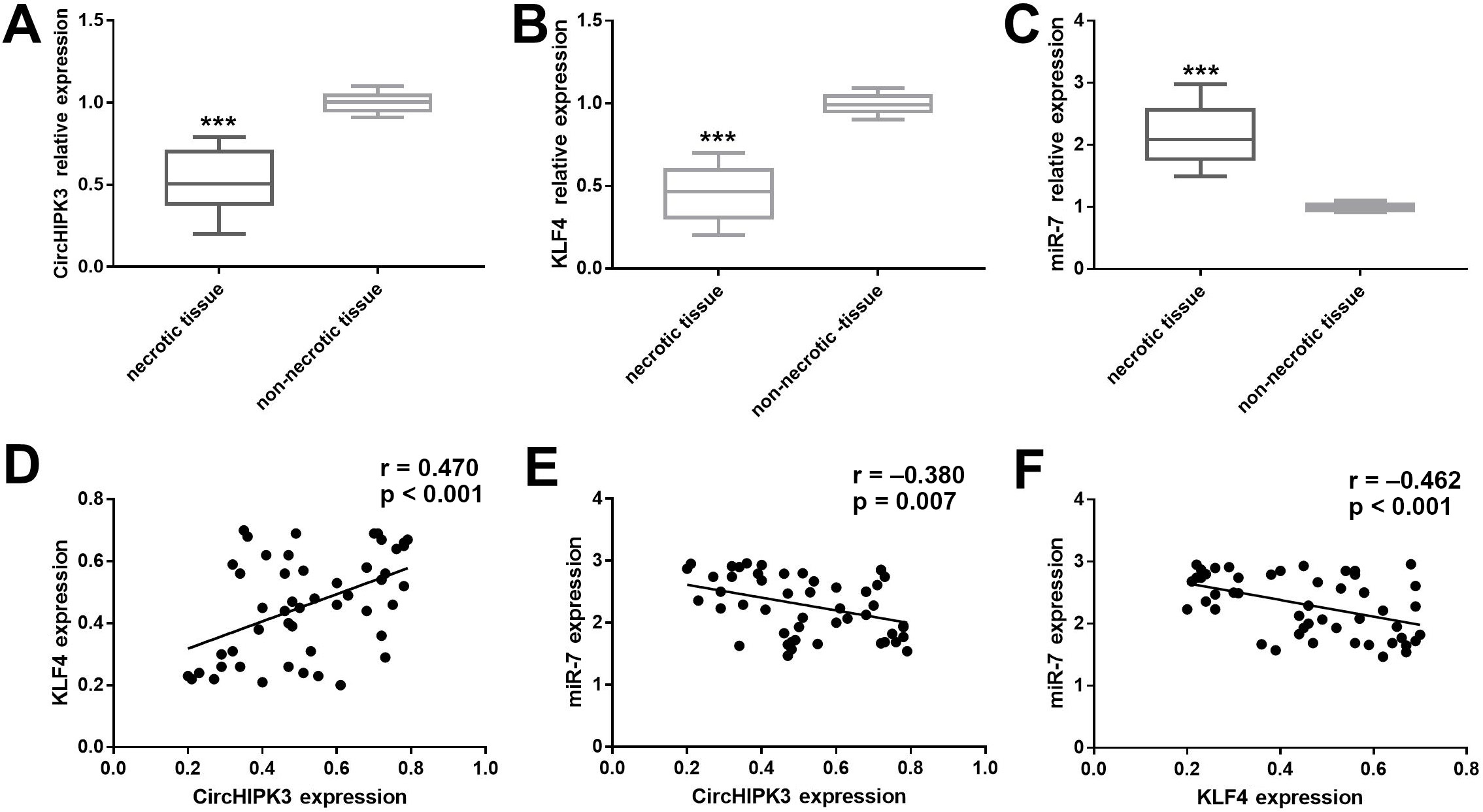

CircHIPK3 expression was downregulated in necrotic tissue in ONFH

The expression of circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4 in necrotic and healthy bone samples was assessed using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). There was a markedly lower circHIPK3 and KLF4 expression in necrotic tissue compared to non-necrotic tissue (Figure 2A,B; circHIPK3: M–W U test, U = 0, p < 0.001; KLF4: M–W U test, U = 0, p < 0.001). Conversely, miR-7 levels were significantly higher in necrotic tissue compared to healthy tissue (M–W U test, U = 0, p < 0.001; Figure 2C). Further correlation analysis demonstrated that circHIPK3 expression in necrotic tissue was positively correlated with KLF4 levels (Spearman’s correlation, r = 0.470, p < 0.001; Figure 2D) but negatively correlated with miR-7 (Spearman’s correlation, r = −0.380, p = 0.007; Figure 2E). In addition, miR-7 expression corresponded inversely with KLF4 (Spearman’s correlation, r = −0.462, p < 0.001; Figure 2F).

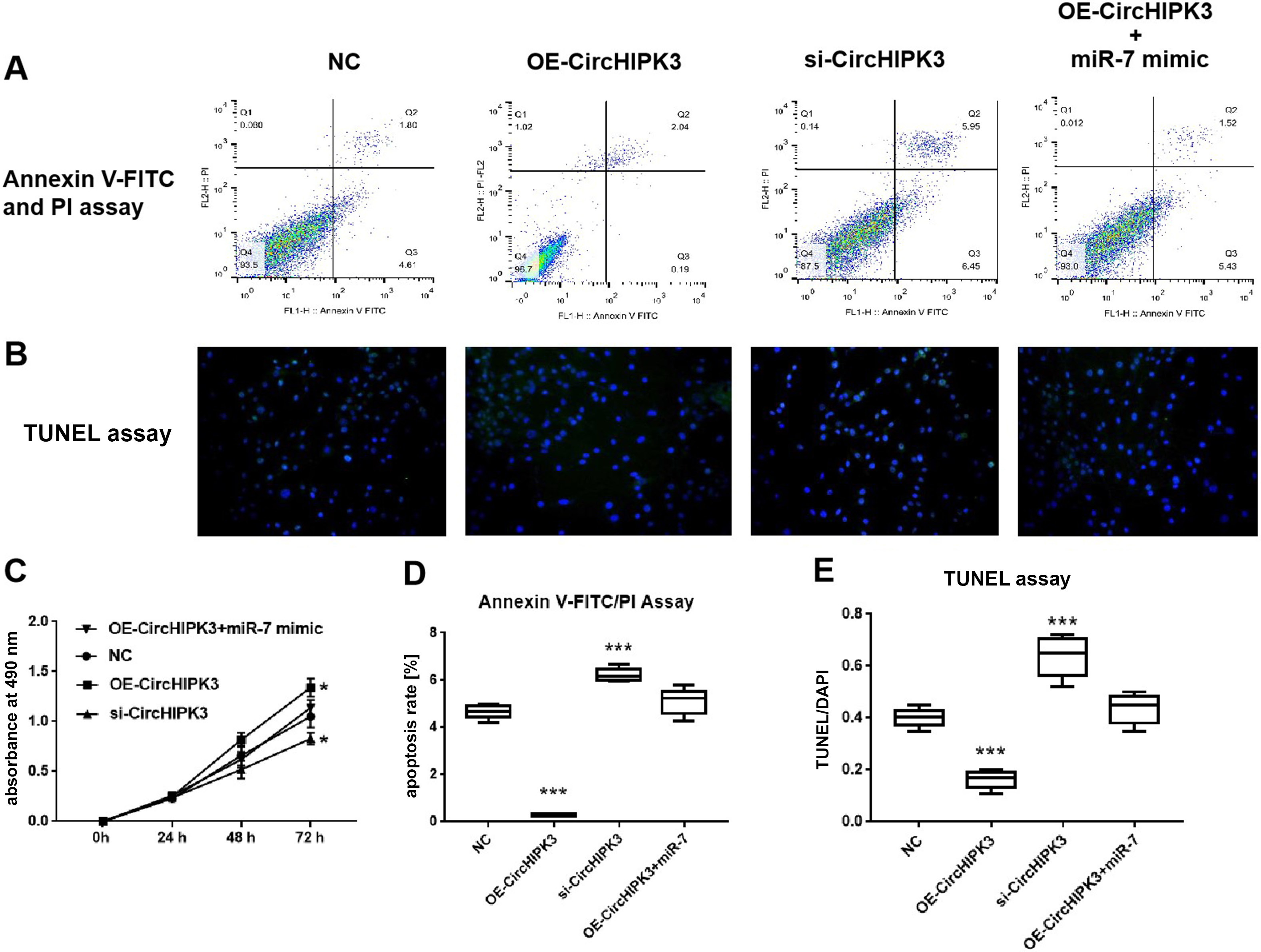

CircHIPK3 upregulation inhibits apoptosis but augments proliferation of BMECs

We postulated that the BMECs would have reduced migratory and proliferative abilities if circHIPK3 expression was downregulated. Based on this assumption, circHIPK3 siRNA, OE-circHIPK3 and miR-7 mimics were transfected into the BMECs (Figure 3A). The CCK-8 assay showed that the proliferation of the BMECs transfected with OE-circHIPK3 was significantly enhanced compared with the NC at 72 h (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, p = 0.025 compared to negative control (NC)), while the proliferation of the BMECs was significantly suppressed following the transfection with circHIPK3 siRNA (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, p = 0.015 compared to NC; Figure 3C). The transfection of OE-circHIPK3 plus miR-7 yielded similar proliferation rates in contrast to NC (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test, p = 0.155 compared to NC; Figure 3C).

To further analyze the impact of circHIPK3 and miR-7 on isolated BMEC growth, the rate of apoptosis was evaluated in the OE-circHIPK3, circHIPK3 siRNA, OE-circHIPK3+miR-7 mimic, and NC. According to the results of the Annexin V-FITC, PI and TUNEL assays, the apoptosis rate was markedly decreased upon circHIPK3 upregulation in contrast to NC (apoptosis FITC: K–W test followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; TUNEL assay: one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; Figure 3A,B,D,E). When the BMECs were treated with circHIPK3 siRNA, the cell apoptosis rate was markedly increased in contrast to the NC (Figure 3A,B,D,E; apoptosis FITC: K–W test followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; TUNEL assay: one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC). The cell apoptosis rates were similar between the OE-circHIPK3+miR-7 mimic and NC.

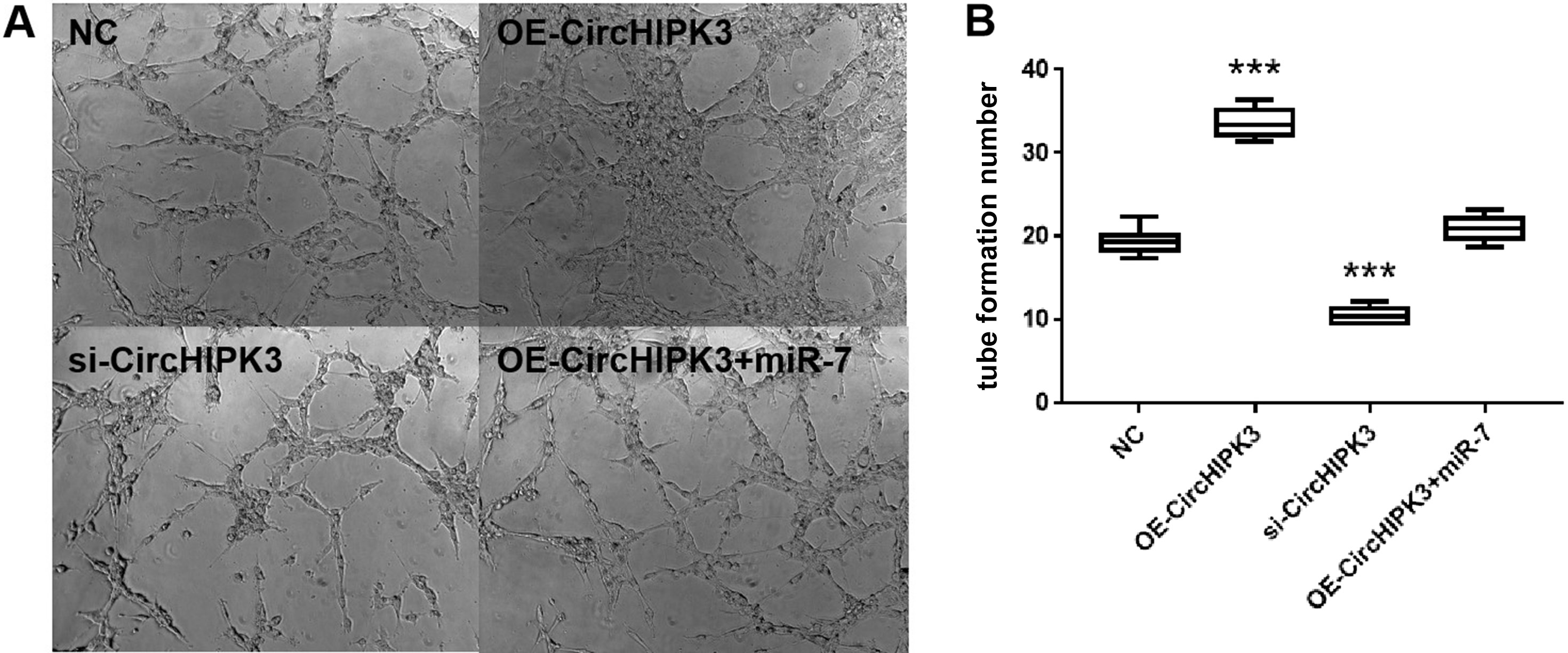

Overexpression of circHIPK3 promotes BMEC migration and angiogenesis

The impact of circHIPK3 upregulation on BMEC tubule formation was observed after 48 h. Accordingly, the total tubule number and density were significantly increased upon circHIPK3 overexpression compared to NC. Conversely, there was a reduction in density and total tubule number upon circHIPK3 silencing. The OE-circHIPK3 in combination with the miR-7 mimic had similar tubule number and density compared with NC (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; Figure 4A,B).

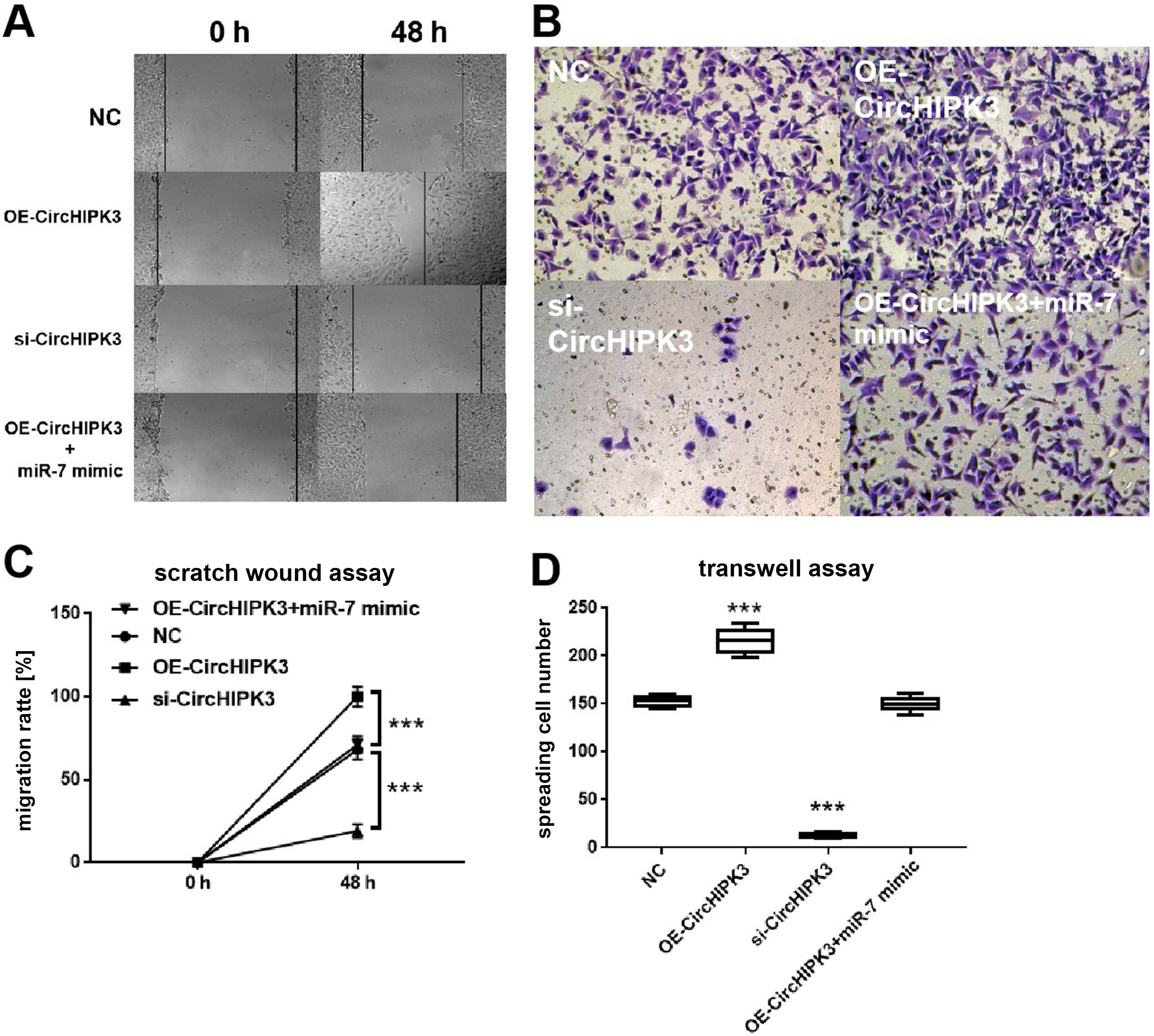

A scratch wound assay allowed us to evaluate the impact of circHIPK3 on BMEC migration. The overexpression of circHIPK3 notably enhanced BMEC motility, as determined by the migration area (Figure 5A,C; one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC), whereas circHIPK3 silencing significantly impaired the motility of BMECs (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC). The OE-circHIPK3+miR-7 mimic group had similar BMEC mobility compared to NC. The pro-migratory ability of the BMECs influenced by circHIPK3 was further confirmed with the transwell assay, which is another widely used method for evaluating cell migration. There was a higher proportion of migratory cells in the OE-circHIPK3 group compared to NC (K–W test followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC), whereas those of the si-circHIPK3 group exhibited a significantly lower proportion of spreading cells. The OE-circHIPK3+miR-7 mimic and NC groups had similar proportions of migratory cells (the K–W test followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; Figure 5B,D).

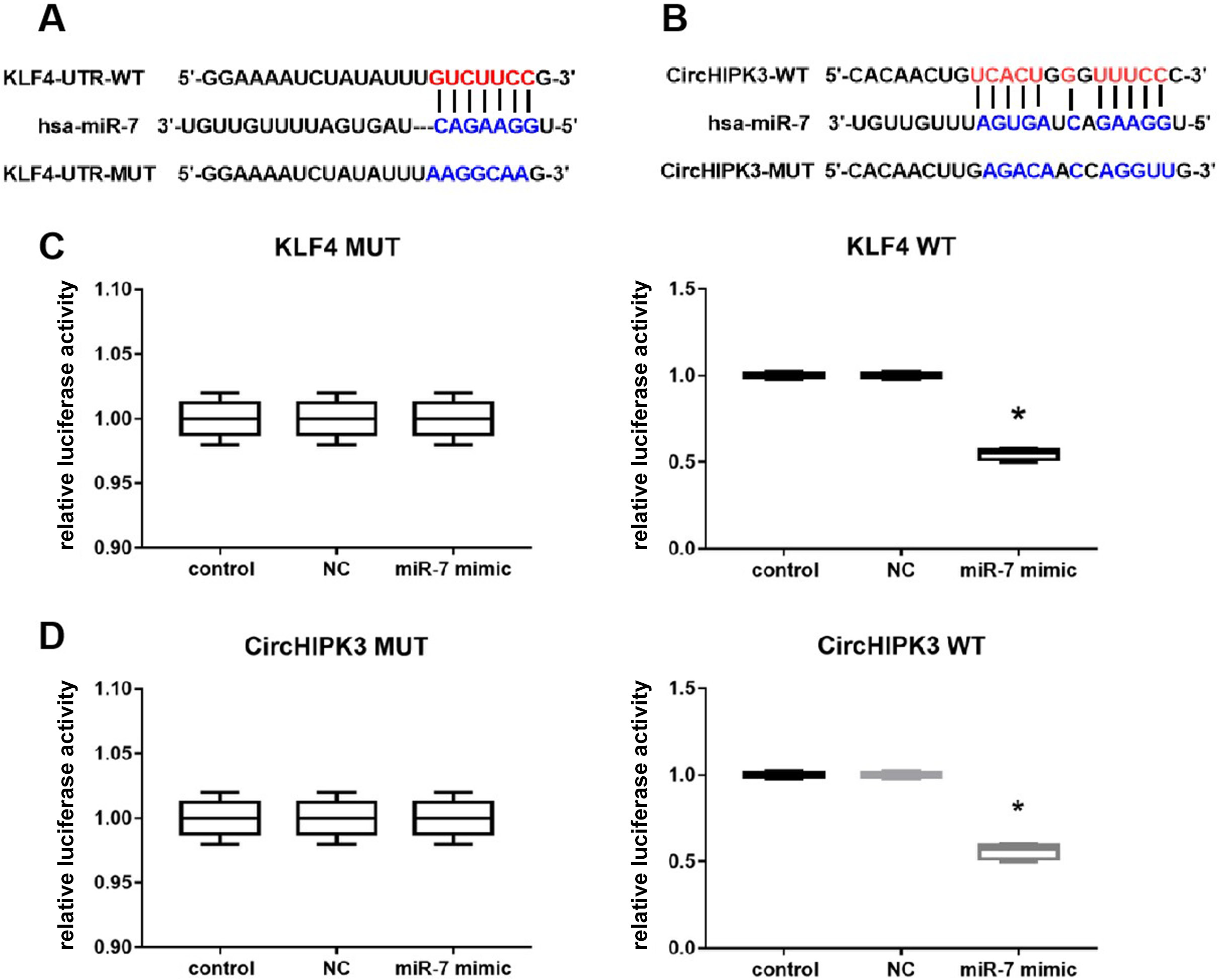

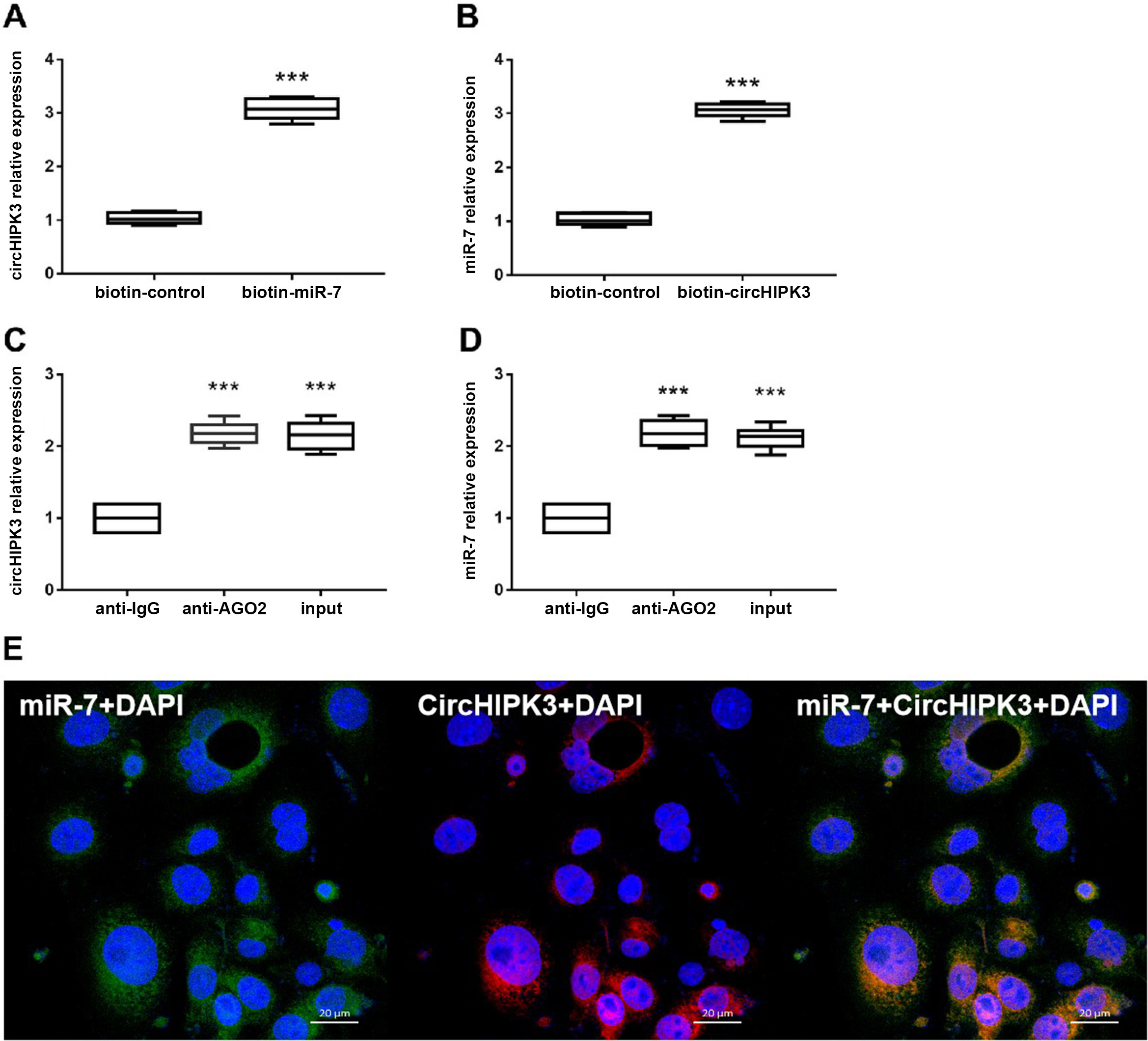

CircHIPK3 functions to sponge miR-7 expressing KLF4 targets

We carried out bioinformatics analysis (using miRBase (https://www.mirbase.org) and starBase v. 3.0 (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/starbase2/)) to predict the likely miRNA target of miR-7 for both KLF4 and circHIPK3. We found that KLF4 was a potential target site for miR-7 (Figure 6A), with circHIPK3 also possessing an miR-7 target site (Figure 6B). The luciferase activity assay demonstrated markedly suppressed luciferase activity of KLF4-WT (wild-type) and circHIPK3-WT reporter genes upon miR-7 mimic exposure compared to the simulated NC (Figure 6C,D) (circHIPK3: K–W test followed by the Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis, p = 0.033 compared to NC; KLF4: one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p = 0.029 compared to NC). However, the miR-7 mimic had no apparent effect on KLF4-WT and circHIPK3-MUT reporter luciferase activities (Figure 6C,D). To further discern the relationship between circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4 in the BMECs, FISH, RIP and RNA pull-down assays were performed. The RIP test showed that the AGO2 antibody significantly enriched the expression of circHIPK3 and miR-7 in contrast to the control immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to anti-IgG; Figure 7A,B). In the RNA pull-down test, circHIPK3 was detected in the miR-7 pull-down sphere in contrast to NC (Student’s t-test, p < 0.001 compared to biotin control; Figure 7C). The miR-7 was also identified in the miR-7 pull-down particles in contrast to NC (Student’s t-test, p < 0.001 compared to biotin control; Figure 7D). The FISH assay colocalized circHIPK3 (red fluorescence) and miR-7 (green fluorescence) in the isolated BMECs (Figure 7E). These findings suggest that circHIPK3 possesses sponge functions by competing for miR-7 with the potential target of KLF4 in BMECs.

Effect of circHIPK3 on KLF4

and VEGF expression

The likely mechanism of circHIPK3 and miR-7 on potential proteins, including KLF4 and VEGF, was studied. After 48 h, we found that circHIPK3 overexpression further increased KLF4 and VEGF protein expression in contrast to NC. On the other hand, transfection of si-circHIPK3 led to a decreased expression of KLF4 and VEGF (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC). Compared with NC, the expression of these proteins was not significantly different after the co-transfection with the OE-circHIPK3+miR-7 mimic, indicating that miR-7 reduced the impact of circHIPK3 on KLF4 and VEGF expression (one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis, p < 0.001 compared to NC; Figure 8A–C). Our findings indicate that KLF4/VEGF signaling activation was promoted by the overexpression of circHIPK3 but suppressed by the overexpression of miR-7.

Discussion

This study investigated the potential role of circHIPK3 in the progression of steroid-induced ONFH. It is the first study to demonstrate a markedly decreased circHIPK3 expression and a notably raised miR-7 expression in necrotic bone tissue in contrast to healthy bone tissue. Our analyses found that the expression of circHIPK3 was negatively associated with miR-7 expression. Further cell studies showed that circHIPK3 augmentation could promote BMEC proliferation, migration and angiogenesis while also attenuating the degree of cell apoptosis. The addition of miR-7 could counteract these effects. The FISH, RNA pull-down, RIP, and luciferase assays revealed a relationship between circHIPK3, miR-7 and KLF4. The upregulation of circHIPK3 enhanced the protein expression of KLF4 and VEGF. These results suggest that circHIPK3 promotes BMEC proliferation, migration and angiogenesis by targeting miR-7 and KLF4/VEGF signaling.

Steroid-induced ONFH is often thought to arise in the setting of frequent steroid consumption.34, 35 In recent years, studies on the epigenetics of hormone-induced ONFH have sought to uncover its molecular pathogenesis and to discover likely miRNA, lncRNA and circRNA targets.36, 37, 38 However, detailed reports on the role of circRNA in this disease have yet to be published. The circRNAs represent novel targets due to their relationship with angiogenesis.

In this study, we established the role of circHIPK3 in the regulation of BMEC angiogenesis, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target in steroid-induced ONFH. The circHIPK3 expression was found to be lower in necrotic bone compared to adjacent non-necrotic bone in ONFH patients. Conversely, miR-7 expression was increased and KLF4 expression was upregulated. A further analysis established that circHIPK3 and miR-7 were inversely correlated. We found that circHIPK3 was localized in the cytoplasm based on FISH studies. The RIP and RNA downregulation experiments suggest that circHIPK3 may affect BMECs through its role on miRNA sponge miR-7.

Angiogenesis is the physiological phenomenon of novel blood vessel formation from existing capillaries. Angiogenesis serves as a pivotal process during bone repair in ONFH. Many circRNAs have been suggested to regulate angiogenesis in both in vivo and in vitro studies.39 For example, Ouyang et al. demonstrated that circRNA hsa_circ_0074834 promoted osteogenic and angiogenic coupling of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs).40 Zhang et al. discovered that hsa_circRNA_001587 could inhibit angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells.41 Another study indicated that circRNA-001175 is able to inhibit apoptosis while enhancing angiogenesis and proliferation in high glucose-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells.42 In our study, we found that overexpressing circHIPK3 promoted BMEC angiogenesis, indicating that circHIPK3 may exert positive effects on bone blood supply in ONFH. Previous studies have demonstrated that circHIPK3 could induce cardiac regeneration and promote blood supply in myocardial infarction. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated an increased VEGF-A activity due to the action of exosomal circHIPK3 derived from hypoxia-induced cardiomyocytes on inhibiting miR-29a activity.43 Another study showed that the overexpression of circHIPK3 promotes proliferation, migration, tubule-forming ability, and subsequent angiogenesis of coronary endothelial cells.44 In addition, we found that circHIPK3 enhanced BMEC migration and proliferation while suppressing apoptosis. All these findings indicate that circHIPK3 could act as a stable biomarker that regulates angiogenesis in steroid-induced ONFH.

The circHIPK3 was found to act as an miR-7 sponge, which regulates angiogenesis through its effect on KLF4 expression. In previous studies, KLF4 has been shown to be a pro-angiogenic factor that acts through the VEGF signaling pathway to promote proliferation, migration and duct formation.45 Therefore, we focused on the KLF4 pathway as a potential target signal pathway. Augmenting circHIPK3 resulted in upregulated KLF4 and VEGF expression. Our study found that circUSP45 regulated VEGF-mediated angiogenesis.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be considered. Although we demonstrated that circHIPK3 increased KLF4 and VEGF signaling by acting as a sponge of miR-7, there may be other yet-to-be-characterized miRNAs that may also be sponged by circHIPK3. More extensive studies on these potential miRNA candidates and their related target proteins and signaling pathways are warranted.

Conclusion

Our study revealed the role of circHIPK3 downregulation in steroid-induced ONFH. The upregulation of circHIPK3 could promote proliferation, migration and angiogenesis through inhibiting apoptosis of isolated BMECs by targeting miR-7 and through activation of KLF4/VEGF signaling. Our study provides a new reference for the diagnosis and treatment of steroid-induced ONFH, but more relevant mechanisms of action and treatment strategies need to be further investigated.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7104863. The package contains Supplementary Statistical File 1, presenting the results of the normality and homogeneity tests.