Abstract

Background. Major depression (MD) is the one of the most debilitating diseases, affecting millions of people all around the world.

Objectives. To establish visual pathway function in untreated individuals with MD.

Materials and methods. In 29 untreated, newly diagnosed, ophthalmologically asymptomatic individuals (58 eyes) with MD (mean age: 47.3 years) and in 29 (58 eyes) of age-, sex- and refractive error-matched healthy controls (mean age: 46.8 years), the following examinations were performed: 1) best corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA); 2) intraocular pressure (IOP); 3) and 4) biomicroscopy of anterior and posterior segment of eye; 5) macular structure (SD-OCT-Zeiss); and 6) pattern visual evoked potentials (PVEPs) measurements according to the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standard (ISCEV-standard PVEPs). An analysis of correlation between the parameters of PVEPs and the depression severity (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD)) was performed. To estimate the diagnostic power of PVEPs test, a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was used. Data were analyzed with the significance level of p < 0.05.

Results. In the study group and in healthy control, the clinical results and macular structure were normal and not different. In the MD group, in PVEPs test (check size: 1°4’and 0°16’), a significant decrease of amplitudes of P100 (AP100), associated with prolonged P100 peak time (PTP100; check size: 0°16’, p < 0.004) were detected. The most frequent abnormality in PVEPs examination in the MD group was AP100 reduction (in 69% of individuals) detected using stimulation check size 0°16’. The statistically significant positive correlation between PTP100 (check size: 0°16’) and HAMD score was found in severe MD (p = 0.03). The analysis of ROC curve revealed the highest sensitivity of 0.759 and specificity of 1.0 for AP100 (0°16’). The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.841 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions. In individuals with newly diagnosed, ophthalmologically asymptomatic and untreated MD, a dysfunction of visual pathway is present without other signs of ocular pathology. The visual pathway dysfunction measured with ISCEV PVEPs has a potential value to be an objective biomarker of MD.

Key words: major depression, visual pathway function, PVEPs

Background

Major depression (MD) is the one of the most debilitating diseases, affecting millions of people all around the world.1 It was reported to be one of the 5 leading causes of years lived with disability.2 Several studies show that visual abnormalities in individuals with MD may occur. Photophobia, perceived dimness, anomalous pre-attentive processing of visual information, and self-reported visual function loss were detected.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Such patients are also more likely to experience vision problems like blurred vision and watery and strained eyes with surrounding pain and eye floaters. The cause of these complains can be disorders of the retina9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 as well as disorders of the brain including visual cortex.16, 17, 18 Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) are visually evoked electrophysiological signals extracted from electroencephalographic activity in the visual cortex, but they depend on functional integrity of central vision at all levels of visual pathway.19 In the available literature, only a few studies, using various methods, described changes in the PVEPs recordings in individuals with MD.20, 21, 22 In 2 studies, the individuals with MD were medicated with antidepressants, so it was not possible to exclude their influence on PVEPs recordings.20, 21 Only the study by Bubl et al. described visual pathway dysfunction in unmedicated group with MD, and revealed abnormal cortical response, which was less pronounced than the retinal response.22 It was the reason why we decided to analyze the visual pathway function in an untreated group of individuals with MD.

Objectives

Our aim was to evaluate visual pathway function in unmedicated patients with MD. We wanted to check if commonly performed, standard ISCEV (International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision) PVEPs recordings are useful in detecting visual pathway dysfunction in individuals with MD.

Materials and methods

Prospective studies were conducted in 2017–2021 in Department of Ophthalmology and Department of Psychiatry at the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland.

In the untreated, ophthalmologically asymptomatic, newly diagnosed 29 individuals (58 eyes) with MD (mean age: 47.3 years, age range: 20–69 years) and in 29 (58 eyes) age-, sex- and refractive error-matched healthy controls (mean age: 46.8 years, age range: 21–65 years), the following examinations were performed: 1) the best corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA; Snellen Table); 2) intraocular pressure (IOP; Pascal tonometer); 3) and 4) biomicroscopy of anterior and posterior segments of the eye; 5) macular structure (thickness: inner limiting membrane to the retinal pigment epithelium (ILM-RPE) average cube, average retinal nerve fiber layer and average ganglion cell layer (GCL) + inner plexiform layer (IPL; Cirrus HD OCT Model 5000, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany); and 6) pattern reversal visual evoked potentials measurements (PVEPs according to ISCEV standards)19 (RetiPort; Roland Consult GmbH, Brandenburg an der Havel, Germany). Stimulus parameters were as follows: black and white reversing checkerboard with 2 check sizes equal to 0°16′ and 1°4′, with the luminance of the white elements of 120 cd/m2, and the contrast between black and white squares of 97%. Parameters of the recording system were as follows: amplifier range ±100 μV/div; filters 1–100 Hz; sweep time of 300 ms, and artifact rejection threshold of 95%. Two trials of 100 artifact free sweeps for each check size were obtained and averaged off-line. The analysis included the amplitude (A) and the peak time (PT) of the P100 wave (AP100 and PTP100).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Pomeranian Medical University (approval No. KB-0012/107/16 granted on October 17, 2016). The individuals with MD were assessed psychometrically with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD).23, 24 Individuals with MD accompanied by other psychiatric disorders, as well as ocular and systemic diseases with known influence on the retinal function were excluded. The MD individuals with poor focusing ability were also excluded.

Statistical analyses

The average value of the PVEPs parameters from the right and left eye from the MD and the control group were measured for further statistical analysis. Central tendency and dispersion measures of analyzed variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (M ±SD). The assumption of normality was checked using the W Shapiro–Wilk test (Table 1). With reference to the normality tests, the normal ranges were determined based on the values of parameters from the control group. In the case of normal distribution of the variables, the normal range was between −2SD and +2SD; in the absence of normality, the normal range was between 2.5 and 97.5 percentile. The values of parameters (amplitudes and peak times of the P100 wave with 1°4’ and 0°16′ check sizes) between the 2 groups were compared. To compare the parameters between the groups, the Student's t-test was used in the case of normal distribution (taking into account the homogeneity of variance and Welch’s correction) of variables, or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test in the case of non-normal distribution. An analysis of the correlation (Spearman’s rank correlation test) between the parameters of PVEPs and HAMD scale score was performed. To estimate the diagnostic power of PVEPs test, the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were was used. The results were considered as statistically significant with p < 0.05.

Results

In the MD group and the healthy controls, the clinical results were as follow: the BCDVA – 1.0 ±0.1 (both groups), IOP – between normal limits, biomicroscopy of anterior and posterior segment of the eye – normal, and normal macular structure (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the age between the 2 groups (MD: mean age 47.3 years, healthy controls mean age: 46.8 years, Student’s t-test; df = 56; p = 0.731). In the MD group, the HAMD mean was equal to 26.4 ±6.6. There was a significant difference in the psychometric measure between the MD and the control group (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in mean age between the 2 groups (Student’s t-test; df = 56; p = 0.731). In the MD group, the HAMD score mean was 26.4 ±6.6. There was a significant difference in the psychometric measure between the MD and the control group (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.001).

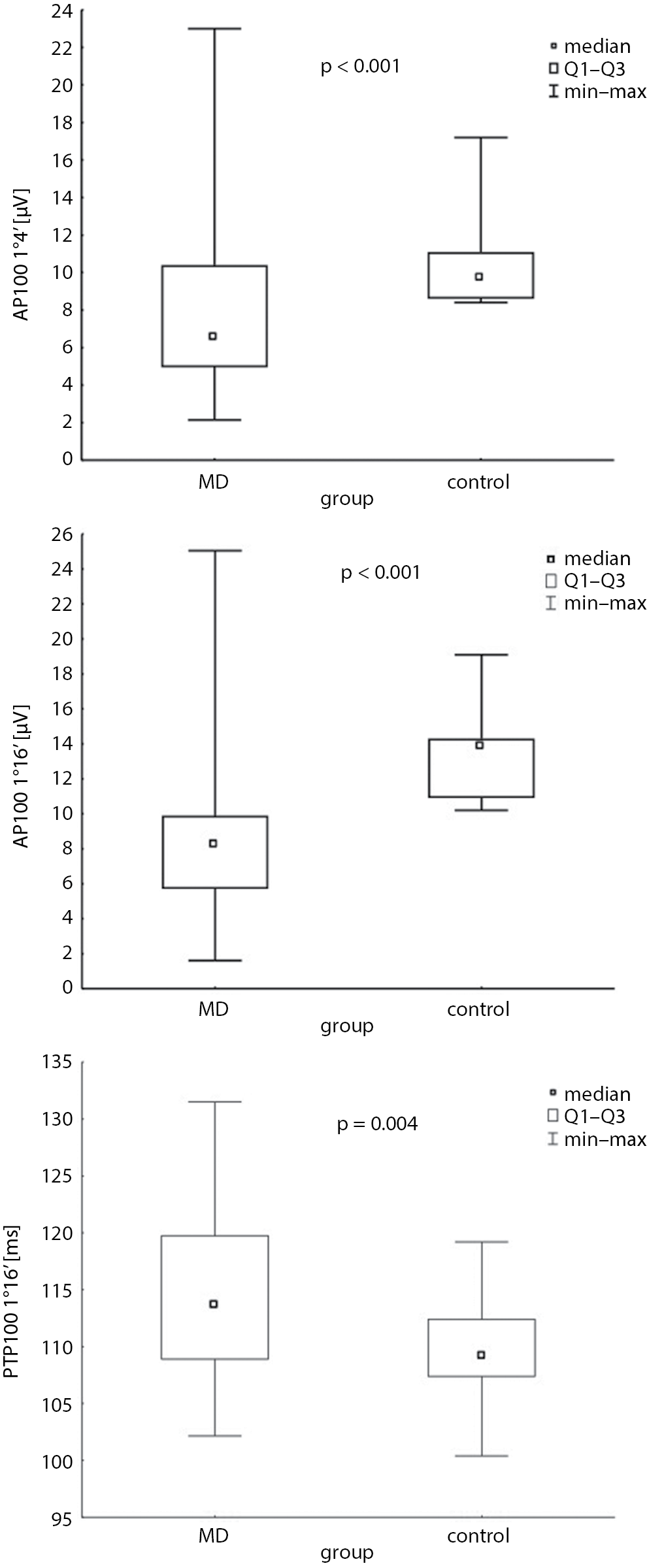

Table 3 presents comparisons of PVEPs parameters such as AP100 and PT100 (check sizes: 0°16′ and 1°4′) between the MD and the control group. In the MD group (Table 3, Figure 1), a significant decrease of AP100 was achieved (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.001 with 1°4′ and Student’s t-test; df = 56; p < 0.001 with 0°16′). The significant difference of PTP100 between the MD and the control group was also obtained but only for check size 0°16′ (Mann–Whitney U test; p < 0.004), (Table 3, Figure 1).

Comparisons of differences between mean A/mean PT of the P100-wave in patients with MD and mean A/PT of the P100-wave in normal subjects showed no statistically significant differences.

The range of normal values for PVEPs parameters was obtained from 58 eyes of 29 healthy controls. On the basis of the PVEPs normal values, the percentage of abnormal results for the analyzed PVEPs parameters in the MD group was estimated (Table 4). The most frequent abnormality in PVEPs examination in the group of MD individuals was the reduction of AP100 (check size: 0°16′) in 69% of them.

The HAMD results did not correlated significantly with PVEPs parameters. Correlations between PVEPs parameters as well as the severity of depression were also analyzed, adopting a 2-degree division of MD25: mild and moderate (HAMD score 8–23; 11 patients), and severe (score ≥24; 18 patients). The only statistically significant positive correlation between PTP100 (check size: 0°16′) and HAMD score was found in severe MD (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient = 0.5; df = 16; p = 0.033).

The ROC analyses for PVEPs parameters were performed to assess the accuracy of the electrophysiological examination of the visual pathway with reference to MD. In the case of AP100 (check size: 1°4’), the cutoff point was 8.3 µV, with sensitivity of 0.690 and specificity of 1.00. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.775 (p = 0.001). In the case of AP100 (check size: 0°16′), the cutoff point was 9.9 µV, with sensitivity of 0.759 and specificity of 1.00. The AUC was 0.841 (p < 0.001). For the PTP100 (check size: 0°16′), the cutoff point was 115.6 ms, with sensitivity of 0.483 and specificity of 0.897. The AUC was 0.719 (p = 0.001).

Discussion

Results of the present study are consistent with previous PVEPs findings in individuals with MD.22 A study by Bubl et al. indicated a reduction of the retinal contrast gain on the level of ganglion cells in MD individuals.26 The decrease in retinal contrast gain was correlated with the reduction of visual evoked potential amplitude.22 In our study, we did not perform measurements of the contrast gain in the PVEPs. We wanted to check if commonly performed, ISCEV-standard PVEPs recordings (contrast between black and white squares of 97%) are useful in detection of visual pathway dysfunction in individuals with MD. Obtained results in this study strongly suggest that in the untreated, newly diagnosed individuals with MD, visual pathway dysfunction is present without other signs of ocular pathology and can be measured using ISCEV-standard PVEPs recordings (Table 3, Figure 1, Figure 2). The manifestations of detected dysfunction were a reduction of AP100 for used check sizes of stimulation as well as prolonged PTP100 for check size equal to 0°16’.

According to Lam, different sizes of the check stimulus in PVEPs stimulate different part of the retina.27 The large check stimulus elicits more parafoveal response (magnocellular pathway) but small check sizes stimulate a mainly foveal response (parvocellular pathway). We investigated the difference in PVEPs examination between stimulation in the foveal and parafoveal region in patients with MD. Comparative analysis between AP100 and PTP100 after large (1°4′) and small (0°16′) check stimulation showed no statistically significant differences. This results indicated that in untreated individuals with MD, parvo- and magnocellular pathways are evenly disturbed.

If separated eyes of MD individuals were compared to age- and sex-matched normal values from PVEPs examination of controls (Table 4), the most frequent feature was the reduction of AP100 (check size: 0°16′). The only significant correlation found was between PTP100 (check size: 0°16’) and the severe MD measured using HAMD. The lack of correlation between PVEPs parameters in mild and moderate MD suggested that ISCEV-standard PVEPs measurement, contrary to the PVEPs contrast gain, is less useful in estimating MD severity.22

The results of the ROC curve analysis show the predictive potential of PVEPs parameters in evaluation of visual pathway dysfunction in individuals with MD. The areas under the ROC curve for AP100 (check sizes: 0°16′ and 1°4′) and for PTP100 (check size: 0°16’) differed significantly from the random model. According to the proposed classification by Hosmer et al., the AUC for AP100 (check size: 0°16’) had an excellent predictive value (0.8 < AUC < 0.9) while for AP100 (check size: 1°4’) and PTP100 (check size: 0°16’) it was acceptable (0.7 < AUC < 0.8).28 In our model, in the case of AP100 (check size: 1°4′), at the designated cutoff point, 69% of individuals with MD were correctly classified (sensitivity of 0.69) and 100% were correctly classified as healthy (specificity of 1). For AP100 (check size: 0°16’), at the designated cutoff point, 75.9% (sensitivity of 0.759) of individuals with MD and 100% of healthy individuals were correctly classified (specificity 1). A worse result was obtained for the PTP100 (check size: 0°16’), where 48.3% of MD individuals and 89.7% of healthy individuals were correctly classified at the designated cutoff point.

Despite well-known characteristic symptoms of MD like mood dysregulation and impaired cognitive control, depressive disorder might be associated with the visual complaints not explained in the course of routine ophthalmological examination. There is growing evidence that a dysfunction of dopaminergic system has a significant role in pathogenesis of MD.29 The ventral tegmental area as well as mesolimbic and mesocortical pathway play important roles in this regard.30, 31 The occipital cortex receives strong dopamine innervation from the mesocortical dopamine system.32 Moreover, dopamine modulates contrast gain control in the visual pathway in the lateral geniculate body and visual cortex.33 Dysregulation of dopamine level in MD individuals might be responsible for abnormal retinal contrast response and less pronounced cortical response.22 There are some studies suggesting influence of the catecholaminergic dysfunction on the PVEPs recording in MD individuals20, 22, 34, 35 and in another dopamine-related diseases such as Parkinson disease.36, 37 Abnormal PVEPs in our study confirmed previous notions on the connection with the catecholaminergic system changes in MD individuals.

In our study, in the MD individuals, the retinal macular structure was also examined using the OCT test and compared with the controls. We did not find significant changes in the MD group. Our results suggest that due to dysregulation of dopamine level, the visual pathway dysfunction was detected without the presence of structural macular changes. In the past, in individuals with MD, the retinal structure using the OCT test examination was investigated in 5 case-control studies with mixed results.14, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Jung et al. described decrease of ganglion cell inner plexiform layer thickness in individuals with MD.12 Kalenderoglu et al. showed significantly reduced GCL, IPL, and global and temporal superior retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness in the recurrent-MD individuals compared to the first-episode individuals, and in all MD individuals compared with the controls.38 This decrease was more severe in individuals with more severe MD. Liu et al. described thinner RNFL in bipolar disorder and MD patients than in healthy people.42 However, other researchers, like in our study comparing the MD individuals with the healthy controls, found no statistically significant differences in the OCT measures.39, 40, 41

The feature of abnormal ISCEV-standard PVEPs response has clinical relevance. The PVEPs signal might serve as an objective marker of the major depression and has a potential value in monitoring pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment trials. The PVEPs test is commonly used in ophthalmology, is easy to perform, minimally invasive and inexpensive in comparison to other techniques like positron emission tomography (PET) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Abnormal PVEPs in patient without diagnosed MD but with ophthalmic MD signs and normal results of other ophthalmological as well as neuroimaging examinations should be an indication for psychiatric consultation. Major depression should be taken into account in differential diagnosis of patients with suspected subclinical visual pathway diseases.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is the small number of cases, unblinded examination of the MD individuals, as well as possible and not detected poor focusing of the fixation point during the PVEPs test resulting in abnormal results.

Conclusions

The present study results are additional evidence that in patients with MD visual pathway dysfunction is present (as measured based on ISCEV-standard PVEPs). The abnormalities in visual pathway function detected in PVEPs recording have a potential value to be an objective marker of MD. Future studies using the same methodology but with a larger sample size are necessary to confirm such conclusion. The dependence between subjective visual symptoms and severity of visual pathway dysfunction should also be elucidated.