Abstract

Background. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a syndrome characterized by acute decompensation of chronic liver disease associated with organ failures and very high short-term mortality.

Objectives. To assess the incidence and factors predisposing to ACLF in patients with liver cirrhosis hospitalized due to acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB).

Materials and methods. We collected and retrospectively analyzed the data of 89 consecutive patients (59 males (66.2%), median age 53 years (range: 44–62 years), mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score 14.42 ±6.5, median Child–Turcotte–Pugh score 10 (range: 8–11), and acute GIB (72 variceal bleeding and 17 non-variceal bleeding cases). Acute-on-chronic liver failure was diagnosed based on European Association for the Study of the Liver – Chronic Liver Failure Consortium definition.

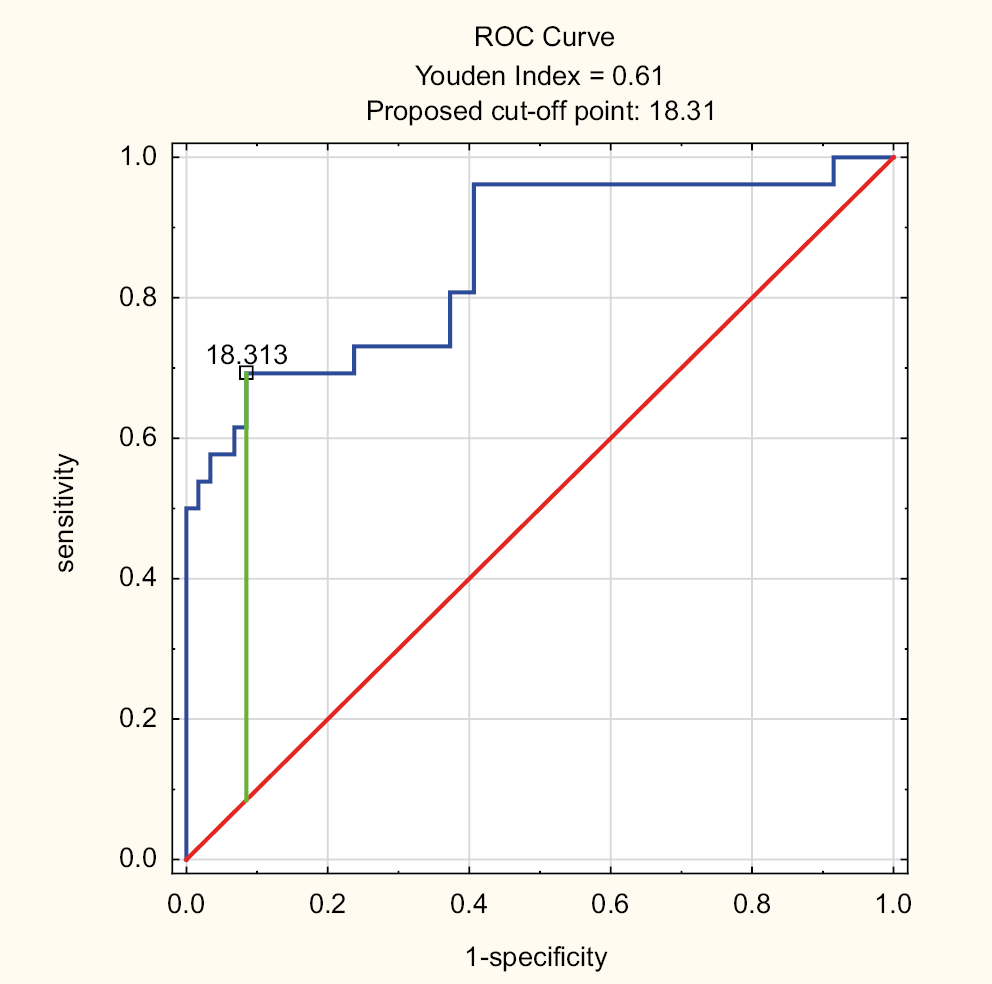

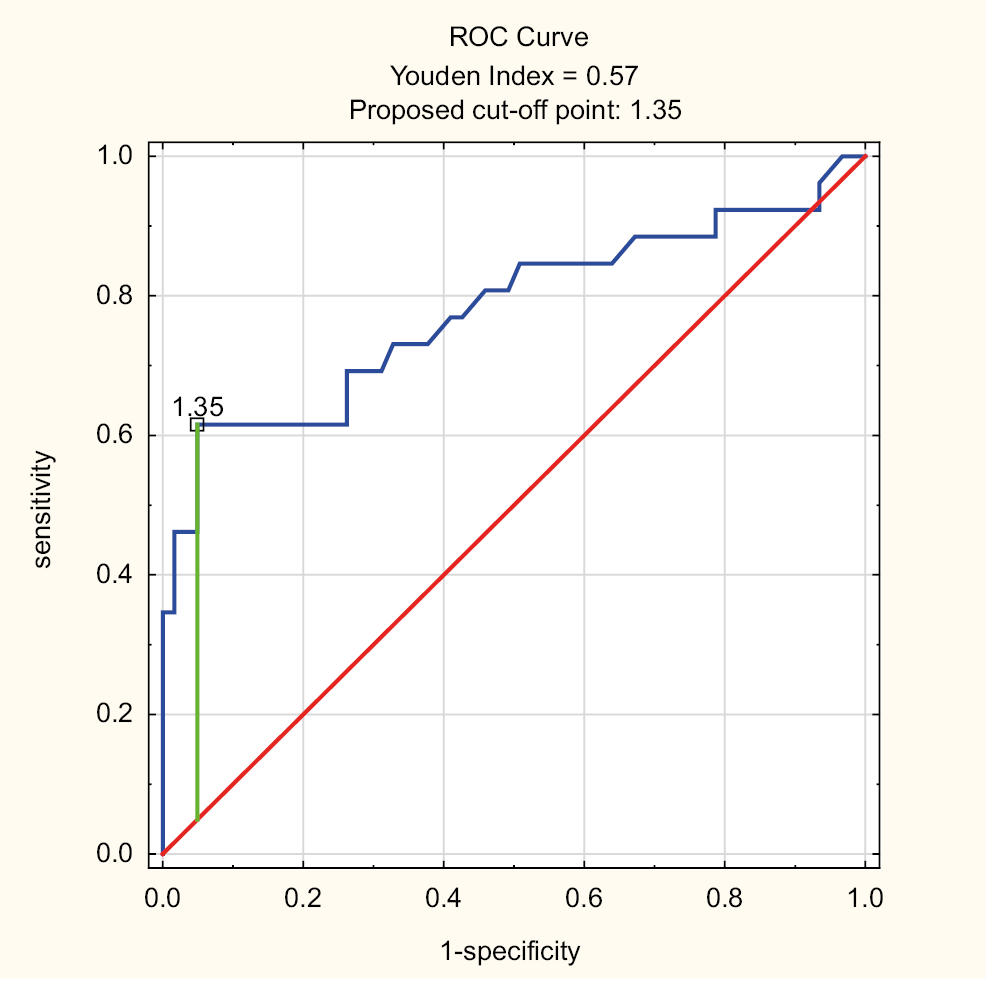

Results. Twenty-seven (30.33%) patients met the criteria of ACLF during hospitalization: 8 (30%) had ACLF grade 1, 13 (48%) had ACLF grade 2 and 6 (22%) had ACLF grade 3. The most frequent organ failures were respiratory (22 (25%)), kidney (18 (20.23%)) and brain (17 (19.1%)) failure. The MELD score value, creatinine level and presence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) on admission were significant predictors of ACLF in the multivariate logistic regression model with optimal cutoff point for MELD score of 18.313 and optimal cutoff point for creatinine level of 1.35 mg/dL.

Conclusions. In-hospital risk of ACLF in cirrhotic patients hospitalized for acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage is high despite successful arrest of bleeding. Elevated creatinine level, MELD score and the presence of HE on admission are the best predictors of ACLF during hospitalization in such patients.

Key words: liver cirrhosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, organ failure, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, acute-on-chronic liver failure

Background

The natural history of liver cirrhosis includes compensated and decompensated phase. The classic hallmarks of decompensated liver cirrhosis are variceal bleeding, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a syndrome characterized by acute decompensation (AD) of chronic liver disease associated with organ failures. While the predicted survival of patients with decompensated cirrhosis is 3–5 years, ACLF has very high short-term mortality exceeding 25%, with a prognosis comparable to the acute liver failure.1, 2 The European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) Consortium and the EASL-CLIF Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis (CANONIC) study provided the evidence-based definition of ACLF in 2013.3 This definition is based on the existence of the failure of 1 of the 6 major organ systems (liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, circulation, and respiration) in patients with acutely decompensated cirrhosis (with or without prior episodes of decompensation).3, 4 The failure of individual organ systems in these patients is assessed using the CLIF-C Organ Failure scale. As defined by EASL-CLIF, ACLF is divided into 3 grades of increasing severity, based on the number of organ system failure.

The Personalised Responses to Dietary Composition Trial (PREDICT) study showed that AD without organ failure (without ACLF) is a heterogeneous condition with 3 major clinical courses: 1) pre-ACLF with high risk of ACLF and high 3-month and 1-year mortality rates; 2) unstable decompensated cirrhosis (UDC) with intermediate mortality rates, high risk of ≥1 readmission, but not leading to ACLF; 3) stable decompensated cirrhosis (SDC) neither requiring readmission to hospital nor leading to ACLF, and showing the lowest mortality.5 Based on results of CANONIC and PREDICT studies, we can identify cirrhotic patients with AD with a high risk of short-term mortality due to ACLF.

In patients with compensated cirrhosis, the major determinants of decompensation are clinically significant portal hypertension and the degree of liver failure. Traditionally, portal hypertension, portosystemic shunting, and hepatic and extrahepatic organ perfusion disorders have been recognized for decades as the main risk factors for complications of cirrhosis. The current view of the physiological mechanism of AD assumes a crucial role of systemic inflammation in the development of AD subphenotypes, including AD-ACLF.6 Systemic inflammation increases across AD-no-ACLF phenotypes from the lowest degree of inflammation in SDC, through moderate in UDC to the highest in pre-ACLF.7, 8 In patients with AD-ACLF, the degree of systemic inflammation correlates also with the number of organ failures, severity of the clinical course and prognosis.6, 9 Variceal bleeding, which is a major complication of portal hypertension, occurs more frequently in UDC than in other AD-no-ACLF phenotypes.10 This phenotype has a complicated clinical course and a relatively high mortality rate, with moderate systemic inflammation at hospital admission. In patients with variceal bleeding and AD-ACLF phenotype, the clinical course seems to depend on the evolution of systemic inflammation.

Objectives

The aim of the study was to assess the incidence and factors predisposing to ACLF in the cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis, hospitalized due to acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) effectively treated endoscopically. The primary endpoint was the occurrence of ACLF in these patients. Secondary endpoints were in-hospital mortality, days of intensive care unit (ICU)/hospital stay, 5-day treatment failure, the rate of repeat endoscopy within 72 h for rebleeding, the need for salvage therapy, and blood transfusion requirements.

Materials and methods

The medical records of patients hospitalized in our department from August 2015 to December 2018 were searched using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes (see Supplementary material for codes and their explanations: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6374308). Data on age, sex, etiology and severity of cirrhosis, sources of acute GIB, and organ failure were collected. We collected and analyzed both the results of laboratory tests on admission and during hospitalization in order to determine ACLF predictors on admission and the incidence of ACLF on admission and during hospitalization.

Definitions

The definitions are presented in the Supplementary material: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6374308.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) cirrhosis diagnosed based on clinical, laboratory and imaging evidence; 2) acute upper GIB confirmed endoscopically and based on clinical symptoms (see above); 3) effective initial resuscitation and successful endoscopic treatment or no need for endoscopic treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) admission for scheduled procedure or treatment; 2) hepatocellular carcinoma outside Milan criteria; 3) severe chronic extrahepatic diseases; 4) ongoing immunosuppressive treatments; 5) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.11

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Medical University of Bialystok, Poland (resolution No. R-I-002/336/2019, of June 27, 2019). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Due to the retrospective design of the study, informed consent of the subjects was not required.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Lilliefors test, and expressed as means (± standard deviation (SD)) or median (interquartile range (IQR)), as appropriate. The equality of variance in the tested samples was assessed with the Levene’s test. Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentage). Continuous data were analyzed with either t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 test. The p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The additional analysis included a stepwise multivariate logistic regression, which was used to identify the best combination of parameters predicting ACLF presence. Only variables which were significantly different between analyzed groups were included into the regression model as predictors. Model was assessed with χ2 test, R2 Nagelkerky coefficient and Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit (GOF) test. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were prepared. Cutoff point calculation was based on Youden’s criterion. Statistical analyses were performed with the STATISTICA v. 13.3 software package (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA).

Results

Of the 1902 hospitalizations identified based on ICD-10 codes (384 hospitalizations due to decompensated liver cirrhosis and 1518 hospitalizations due to acute GIB – see the Supplementary material: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6374308), we collected and retrospectively analyzed data of 89 consecutive patients of Caucasian ethnicity (59 males (66.2%), median age 53 (44–62) years), with cirrhosis (mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score 14.42 ±6.5, median Child–Turcotte–Pugh score 10 (8–11) of various etiologies, and acute GIB, hospitalized from August 2015 to December 2018 at our department.

Twenty-seven (30.33%) patients met the ACLF criteria during hospitalization: 8 (30%) had ACLF grade 1, 13 (48%) ACLF grade 2 and 6 (22%) ACLF grade 3. We were able to confirm ACLF in 7 (7.86%) patients on admission to hospital, based on the available data. Patient data were analyzed considering the presence of ACLF. Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding

Seventy-two patients (80.89%) had variceal bleeding, while 17 patients (19.1%) had non-variceal bleeding. Twenty-one (29.1%) patients with variceal bleeding and 6 (35.29%) patients with non-variceal bleeding had ACLF. Esophageal varices were the most common source of variceal bleeding, while gastric ulcers, erosive esophagitis, duodenal ulcers, and Mallory–Weiss tear were the most common causes of non-variceal bleeding. We found no relationship between the type (variceal compared to non-variceal) and the source of bleeding, and the occurrence of ACLF (Table 2).

Acute cirrhosis decompensation

Forty-three (50%) patients had overt HE, 23 patients (26.44%) had HE grades I/II and 20 patients (23.26%) had HE grades III/V. Hepatic encephalopathy was diagnosed in 24 (40%) patients without ACLF and in 19 (73.08%) patients with ACLF (p = 0.0048).

Ascites was present in 48 patients (54.55%) – 26 (42.58%) non-ACLF patients and 22 (81.48%) ACLF patients (p = 0.0023). Fifty-seven (66.28%) patients were on diuretics (34 (57.63%) in the non-ACLF group compared to 23 (85.19%) in the ACLF group (p = 0.0121). The need for therapeutic paracentesis during hospitalization was observed in 6 patients – 3 (4.92%) patients without and 3 (11.11%) patients with ACLF (p = 0.2878).

A total of 12 (13.48%) patients were diagnosed with clinically significant infections. The most common infections were pneumonia (5 (5.62%)) and urinary tract infection (5 (5.62%)), followed by bacteremia (3 (3.37%)), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (2 (2.25%)) and Clostridium difficile intestinal infection (2 (2.25%)). Infections were more common in the ACLF group compared to patients in the non-ACLF group (8 (29.63%) compared to 4 (6.45%), p = 0.006). Antibiotics were administered in 73 (82.95%) patients (64 (91.43%) patients with variceal bleeding and 9 (52.94%) patients with non-variceal bleeding). Antibiotics were used more frequently in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group (26 (96.3%) compared to 47 (77.05%), p = 0.0268).

Previous episodes of acute decompensation

Fifty (56.18%) patients had a history of previous AD. Of the patients with previous episodes of AD, 16 (32%) had ACLF, while 11 (28%) patients had ACLF despite no prior AD. The history of previous AD did not affect the occurrence of ACLF during current hospitalization (p = 0.699).

Organ failures

The most frequent organ failures as defined by EASL-CLIF score were respiratory (22 (25%)), kidney (18 (20.23%)) and brain (17 (19.1%)) failures, followed by coagulation (7 (7.87%)), circulation (6 (6.98%)) and liver (4 (4.49%)) failures (Table 3). Among patients with organ failures, 20 (52.63%) patients had single organ failure, 13 (34.21%) patients had 2 organs failures, 2 (5.26%) patients had 3 or 4 organs failures, and 1 (2.63%) patient had failure of 5 organs.

In-hospital mortality

There were 7 deaths in the study group: 6 (24.0%) in patients with ACLF and 1 (1.61%) in a patient without ACLF. Estimated probability of dying in the ACLF group calculated based on CLIF-C ACLF score, age and white blood cell (WBC) count was: 24.0% (range: 13–41%), 42.0% (range: 31–61%), 47.0% (range: 41.0–66.0%), and 56.0% (range: 50.0–73.0%) at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. The estimated probability of death based on the CLIF AD score in the non-ACLF group was: 3.0% (range: 1.0–5.0%), 8.0% (range: 5.0–14.0%), 13.5% (range: 9.0–21.0%), and 24.5% (range: 18.0–34.0%) at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. Both CLIF-C ACLF score and CLIF AD score (at 1 month) allowed for a reliable assessment of probability of death during hospitalization in patients with ACLF and patients with AD without ACLF, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in the number of deaths <5 days between the groups – 1 (1.67%) ACLF patient compared to 1 (4%) non-ACLF patient; p = 0.5. However, the overall number of in-hospital deaths was significantly higher in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group: 6 (24%) compared to 1 (1.61%), respectively (p = 0.002).

5-day treatment failure

Five-day treatment failure was found significantly more frequently in patients with ACLF compared to non-ACLF group: 6 (22.2%) compared to 2 (3.23%), respectively (p = 0.008). The rate of repeat endoscopy within 72 h for rebleeding was significantly higher in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group: 7 (25.93%) compared to 3 (4.84%), respectively (p = 0.0075). No statistically significant differences were found in the need for salvage therapy.

The use of blood products

Red blood cell concentrate was used significantly more frequently in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group: 33 (53.23%) compared to 21 (80.77%), respectively (p = 0.017). The frequency of using fresh frozen plasma, platelet concentrate and cryoprecipitate were comparable between groups (11 (18.03%) compared to 8 (29.63%) (p = 0.265), 13 (21.31%) compared to 4 (14.81%) (p = 0.568) and 0 (0%) compared to 1 (3.7%) (p = 0.307), respectively).

Multivariate logistic regression

Parameters which were significantly different between the groups were included into the multivariate logistic regression model with ACLF as outcome variable. Stepwise logistic regression recommended a model with 10 parameters: the presence of HE, ascites, infection, rebleeding during hospitalization, the use of diuretics, red blood cell concentrate, the value of the MELD score, and WBC, creatinine and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.

The MELD score, creatinine level and presence of HE were significant in the model (Table 4). The model was validated with χ2 test, which confirmed that all variables jointly are significant (p < 0.001). The R2 Nagelkerky coefficient was on a moderate level (63%). The additional assessment with Hosmer–Lemeshow GOF test (p = 0.495) confirmed good fit of the model to the data.

To ascertain the optimal cutoff point for MELD score and creatinine level as predictors for ACLF, ROC curves were prepared (Figure 1, Figure 2). For MELD score, the analysis resulted in the area under the curve (AUC) = 0.853, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): [0.759; 0.948]. The optimal cutoff point for MELD score was 18.313, with ACLF prediction for MELD score ≥18.313. Sensitivity and specificity of the analysis were 69.2% and 91.5%, respectively. Accuracy of the test (ACC) was on the level of 84.7%, meaning 84.7% of all patients were correctly identified as ACLF patients based on the MELD score cutoff point of 18.313. For creatinine level, the analysis resulted in the AUC = 0.779, 95% CI: [0.656; 0.902]. The optimal cutoff point for creatinine level was 1.35 mg/dL, with ACLF prediction for creatinine ≥1.35 mg/dL. Sensitivity of the analysis was 61.5% and specificity was 95.1%. The ACC was on the level of 85.1%.

Discussion

The efficacy of endoscopic and pharmacological treatment of acute GIB has improved significantly during the last decades.12 Nevertheless, despite high efficiency of current methods in achieving hemostasis and reducing the frequency of early bleeding relapses, mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding remains high.13 This disparity indicates that the clinical outcome depends not only on successful stopping of bleeding, but primarily on the severity of underlying chronic liver disease and the development of complications.14, 15 Acute-on-chronic liver failure is one such complication which potentially can contribute to increased mortality after GIB. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a known trigger of ACLF. However, the relationship between GIB in cirrhotic patients and ACLF is not well understood.

In this study, we analyzed the data of 89 consecutive cirrhotic patients admitted to our hospital due to gastrointestinal hemorrhage. All patients included in the study were subsequently hospitalized in our department after fluid resuscitation and achieving hemostasis. The incidence of ACLF in these patients during hospitalization was very high (30.33%), despite effective initial treatment of GIB. The in-hospital mortality in patients with ACLF was also high and exceeded 24%. On the other hand, in-hospital mortality in patients without ACLF was 8 times lower. These data indicate that cirrhotic patients with acute GIB are a heterogeneous group in terms of prognosis, and the risk of death in these patients depends primarily on the occurrence of ACLF. Of the organ failures, respiratory failure was most frequently found, followed by kidney and brain failure.

The relationship between the type and number of precipitants and the clinical course of patients hospitalized with AD-no-ACLF and AD-ACLF phenotypes has been investigated previously. The PREDICT study identified 4 precipitants associated with the AD-ACLF phenotype: proven bacterial infections, severe alcoholic hepatitis, GIB with shock, and toxic encephalopathy.6 In the present study, we identified 3 major risk factors for ACLF in patients admitted to hospital for gastrointestinal hemorrhage: high MELD score value, elevated creatinine and HE. Two of the 3 parameters (bilirubin and International Normalized Ratio (INR)) assessed in MELD are used in Maddrey’s discriminant function for alcoholic hepatitis. Therefore, a high MELD score could, in fact, indirectly indicate a higher frequency of alcoholic hepatitis in the ACLF group. Nevertheless, due to the small group of patients, it was not possible to perform separate analyses in subgroups of different etiology. Increased creatinine level could indicate a higher frequency of prerenal renal failure in the ACLF group, resulting from more severe bleeding. Finally, some cases of HE may in practice be a toxic, drug-induced encephalopathy – due to the retrospective design of the study we were unable to distinguish between these cases.

On account of the dynamic clinical course of AD-ACLF, precipitants most often occur in close association with ACLF.6 However, to the best of our knowledge, the exact time interval from triggering to ACLF has not been investigated so far. The assessment of the temporal relationship between the precipitant and ACLF is an interesting issue that requires a new prospective study with close monitoring of parameters of organ systems failure.

In addition to more severe liver failure, higher CRP and WBC values were found in the ACLF group compared to non-ACLF group on the admission. In our study, bacterial infections were more common, and antibiotics were also more often used in the ACLF group compared to non-ACLF group. The effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the mortality, the incidence of infections and the recurrence of bleeding in cirrhotic patients with upper GIB has been confirmed previously in a meta-analysis of 12 studies.16 However, studies included in the meta-analysis did not assess the effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on the incidence of ACLF. Antibiotic prophylaxis (ceftriaxone or ciprofloxacin) has been used in most patients with variceal bleeding and in a significant proportion of patients with non-variceal bleeding in our study. Interestingly, ACLF occurred despite the widespread, prophylactic use of antibiotics. This may indicate the need to individualize antibiotic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients with GIB at highest risk of ACLF.

The issue of identifying patients with the highest risk of mortality and recurrent bleeding is currently of great interest. In a recent study, it was shown that ACLF in patients with acute variceal bleeding almost doubled the risk of recurrent bleeding.17 Furthermore, ACLF was, along with hepatocellular carcinoma, the strongest predictor of short-term mortality in these patients, with an almost threefold increased risk. Interestingly, it was also shown that transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) could improve survival in patients with ACLF and acute variceal bleeding. Kumar et al. analyzed the determinants of mortality in patients with cirrhosis and uncontrolled variceal bleeding.18 The ACLF was found in the majority (68.4%) of patients during hospitalization and it was the strongest determinant of the 42-day and 1-year mortality rates that increased with increasing ACLF grades. Other mortality predictors identified were age and systemic inflammation reflected by the WBC. Importantly, the beneficial effect of the rescue TIPSS was also shown in this study, but only in patients with ACLF. The authors concluded that TIPSS should be offered to these patients. In turn, Lv et al. showed that Chronic Liver Failure Consortium Acute Decompensation Score (CLIF-C ADS) outperforms active bleeding at endoscopy and other prognostic models in predicting 6-week and 1-year mortality.19 This model may be useful in qualifying patients with Child–Pugh B cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding for early TIPSS. Finally, in a recent study, it was shown that variceal bleeding has increased mortality compared to non-variceal bleeding only in males.20 Therefore, the authors suggest a particularly close follow-up after endoscopy in this group of patients with cirrhosis. Nevertheless, in our study, we did not confirm the relationship between the sex and the outcome.

Recent studies suggest comparable mortality after variceal and non-variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients.15, 16 The type of GIB (variceal compared to non-variceal) seemed not to significantly affect the risk of ACLF in our study, which indirectly confirms the results of recent studies.21, 22 On the other hand, the risk of ACLF depended on the severity of the bleeding, reflected by 5-day treatment failure and rebleeding rate. The rate of repeat endoscopy within 72 h for rebleeding and 5-day treatment failure (defined as death within 5 days and active bleeding such as spurting or oozing blood or fresh blood contents in the stomach on repeat endoscopy) were significantly higher in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group. The second investigation derived from the PREDICT study showed that GIB with shock is a significant risk factor for AD-ACLF phenotype.6 According to the current study protocol, patients were enrolled after hemodynamic stabilization and stopping GIB, which was performed in the ICU. Therefore, we were unable to directly analyze the impact of hemorrhagic shock on the incidence of ACLF.

Limitations

There are several limitations of our study. First, the study was retrospective, and the data obtained were limited to patients’ medical records. Second, the number of patients with variceal bleeding was relatively small. Therefore, results regarding the effect of the type of bleeding on ACLF should be interpreted with caution. Third, ACLF was diagnosed in only a few patients on admission to hospital. We are aware that in some of them, the bleeding was a complication of ACLF and not a trigger of ACLF. Based on the available data, we were not able to determine which patients developed ACLF following a hemorrhage prior to hospitalization and in which bleeding was a complication of ACLF. Although the latter situation probably concerned only a few patients with ACLF at admission, this should be considered when interpreting our results. And finally, this is a single-center study with a relatively small number of patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in-hospital risk of ACLF in cirrhotic patients hospitalized for acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage is high despite successful bleeding arrest and widespread use of antibiotics. Elevated creatinine levels and MELD score, and the presence of HE on admission are the best predictors of ACLF during hospitalization in these patients. Patients with liver cirrhosis after gastrointestinal hemorrhage are particularly at risk for respiratory failure, followed by kidney and brain failure.

Data availability

The Supplementary data are available at https://doi.org/

10.5281/zenodo.6374308. The package consists of the following files:

1. Supplementary definitions.

2. Explanations of ICD-10 codes.

3. Fig. S1. Search results of the medical records of patients hospitalized in the department from August 2015 to December 2018.

4. Supplementary Table 1. Verification of assumptions of statistical tests (t-test or Mann–Whitney U test).