Abstract

Background. Isoflurane can significantly induce inflammation in children without surgical stress. The toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is closely related to noninfectious inflammation in the brain.

Objectives. To investigate the role of TLR4-small interfering RNA (siRNA) in learning and memory impairment in young mice induced by isoflurane.

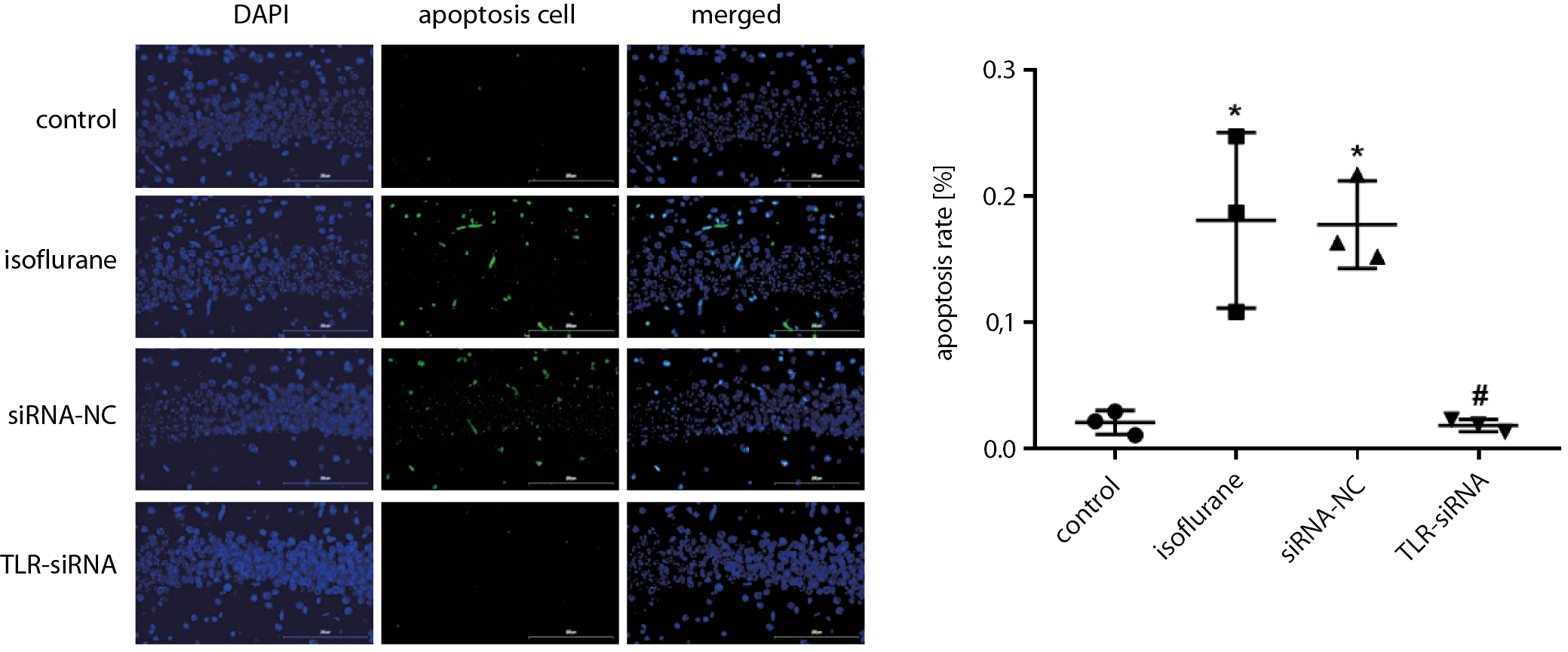

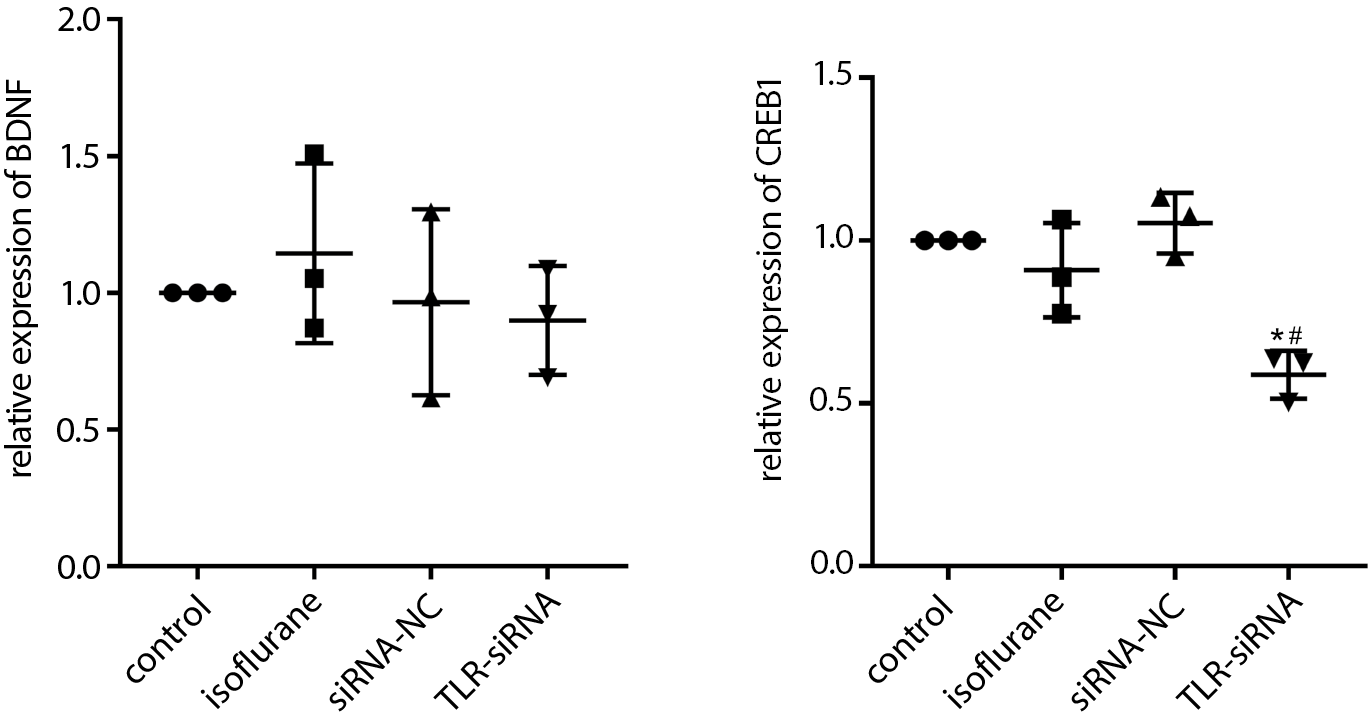

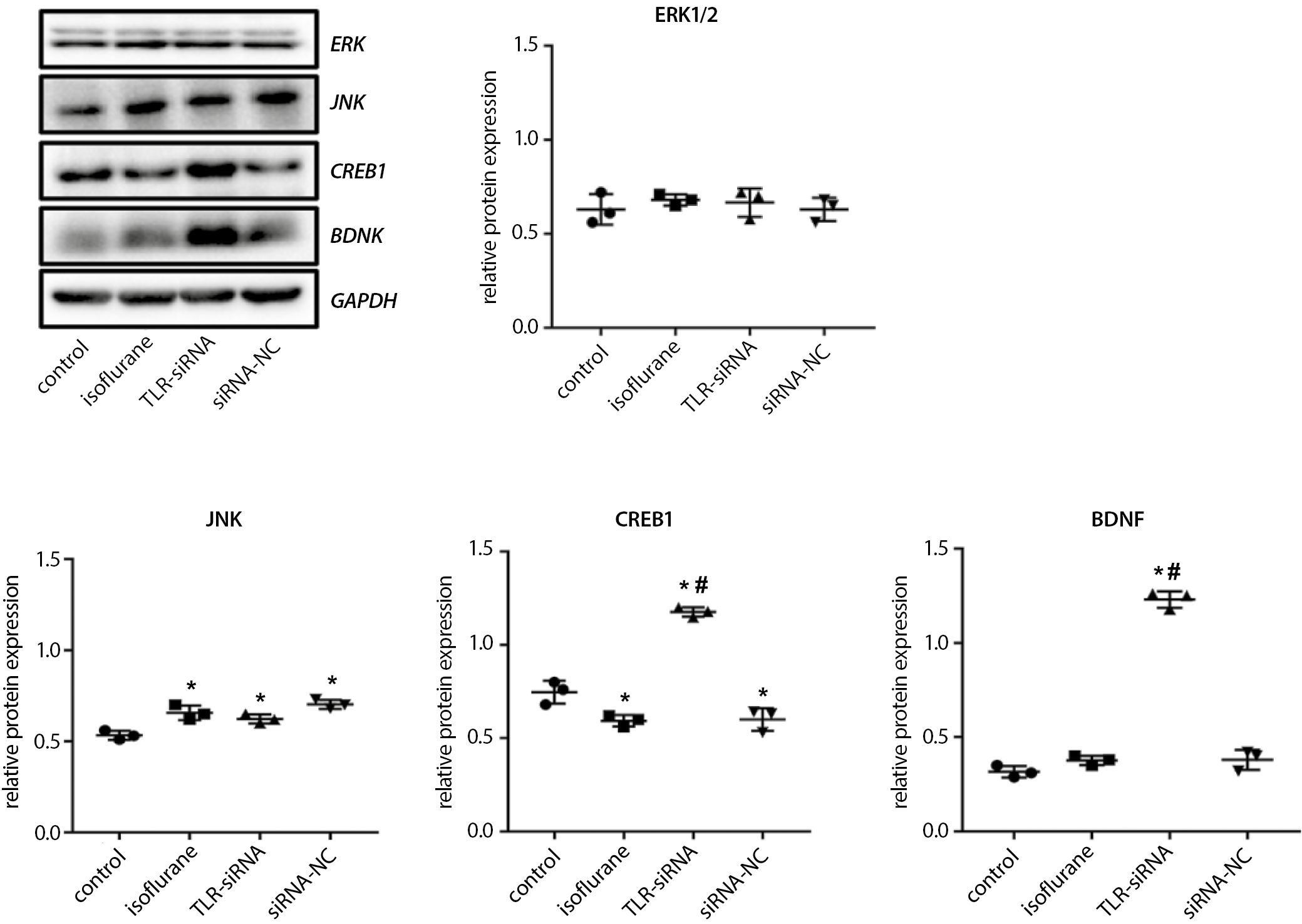

Materials and methods. The C57 newborn mice were randomly allocated into normal control (control), isoflurane anesthesia (isoflurane), TLR4 interference empty vector+isoflurane anesthesia (siRNA-NC), and TLR4 interference+isoflurane anesthesia (TLR-siRNA) groups. Their behavior and pathological condition were detected using Morris water maze and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, respectively. The TLR4, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein 1 (CREB1) mRNA expressions were detected using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 were detected by means of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Apoptosis rate was detected with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). The TLR4, TNF-α, IL-6, BDNF, CREB1, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) protein expressions were detected using western blot (WB).

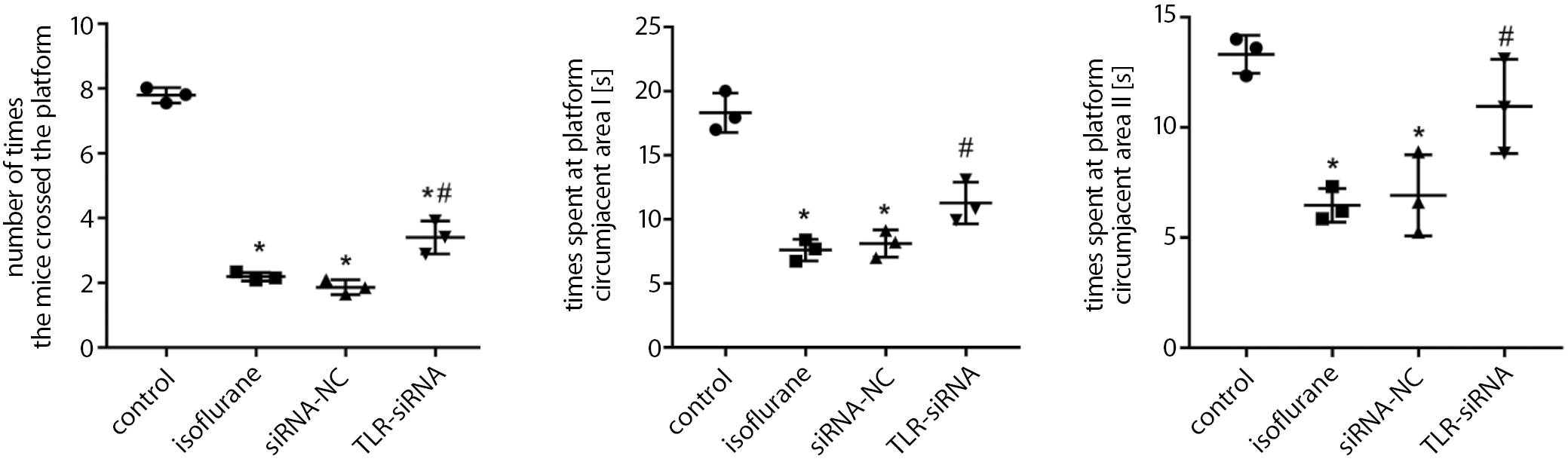

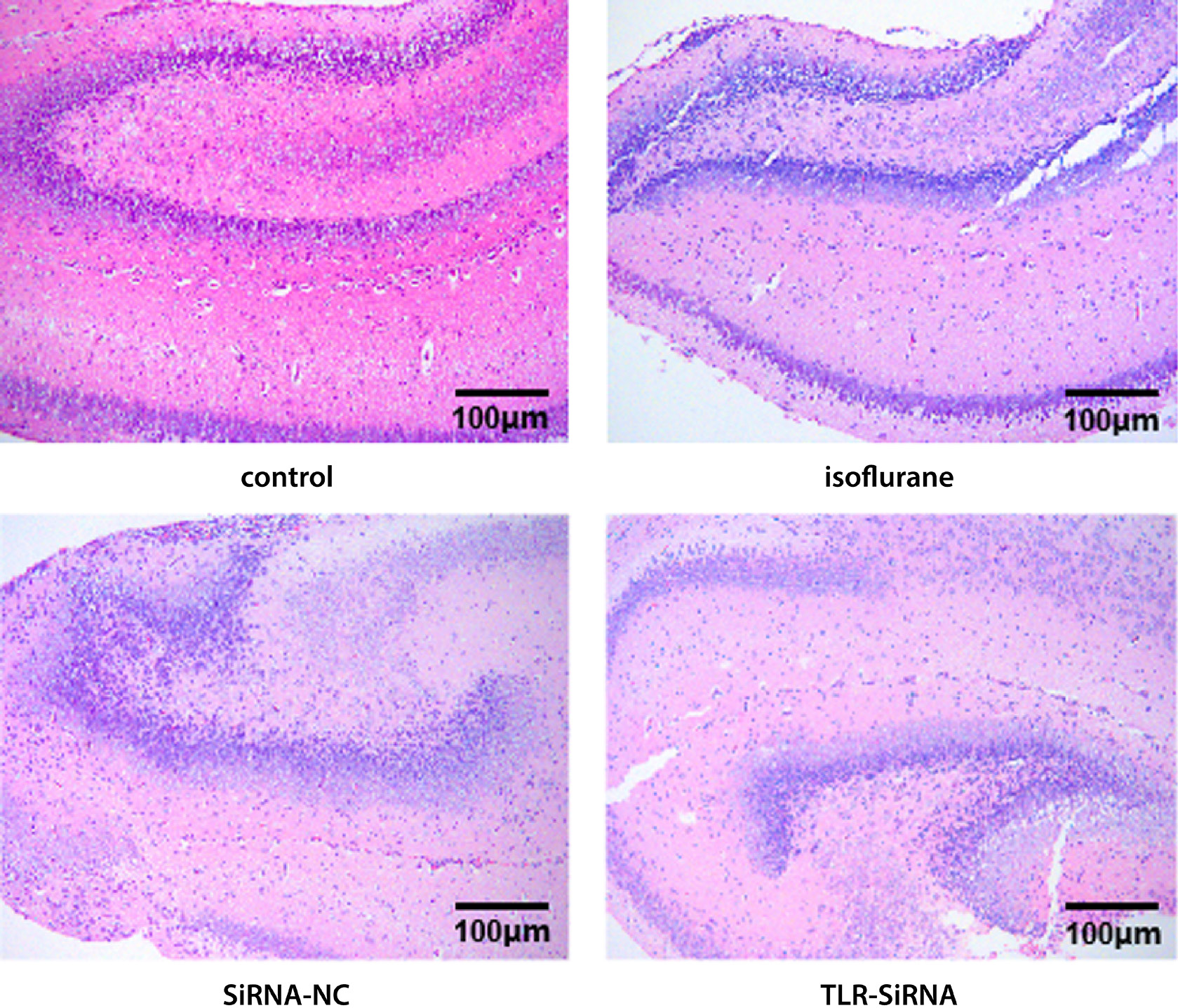

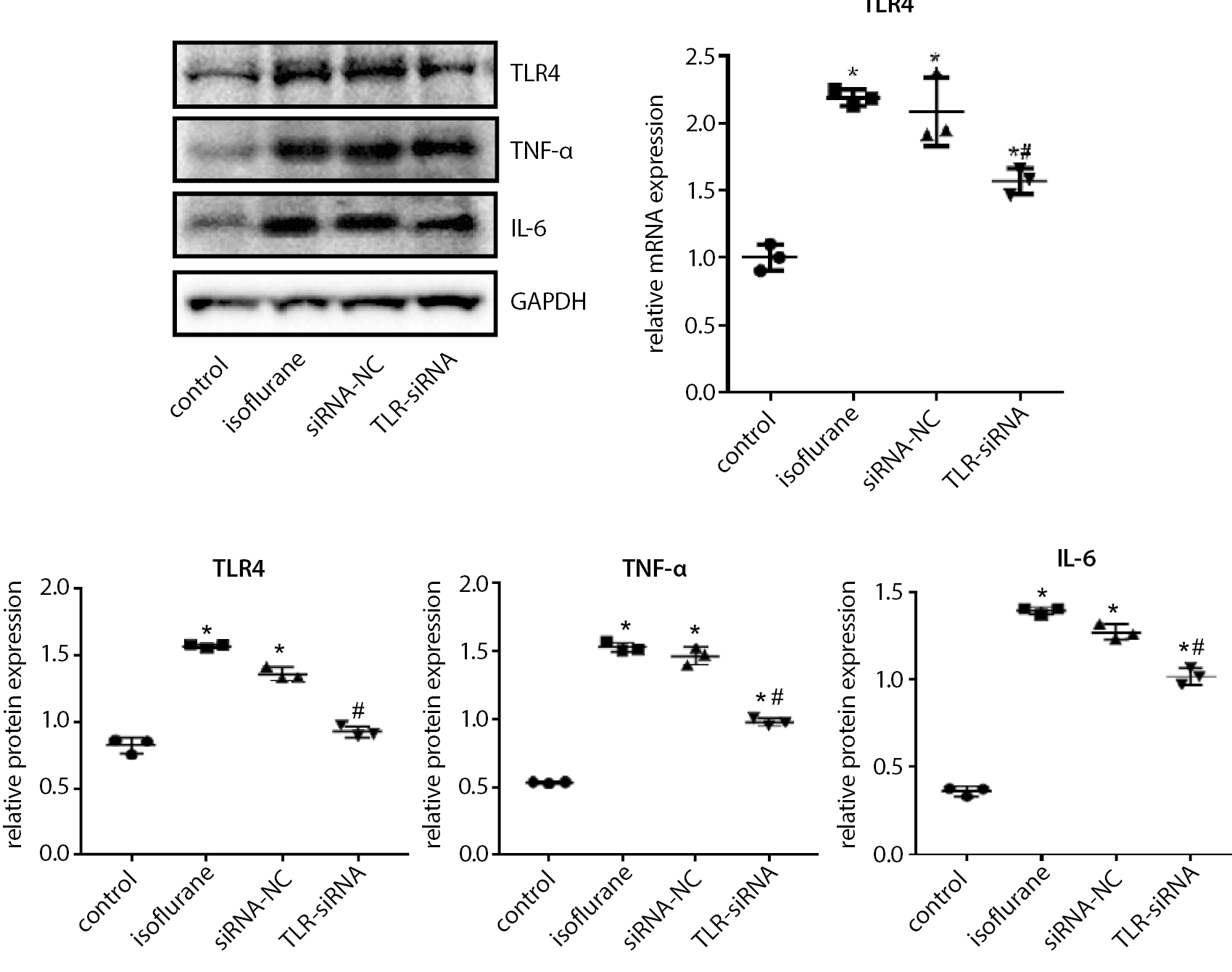

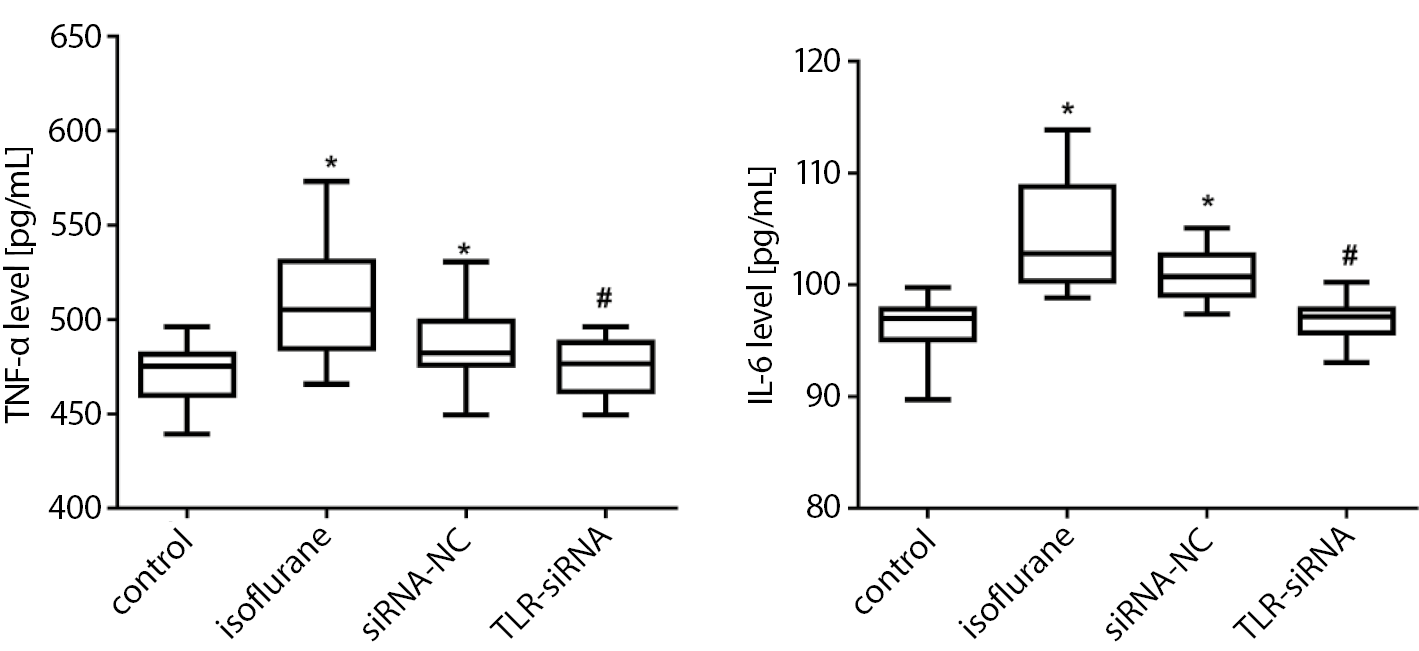

Results. Compared with the control group, the number of times the mice crossed the platform, and the time spent at the circumjacent area I and II of the platform were significantly decreased in the isoflurane group; the TLR4, TNF-α and IL-6 expressions were significantly increased in the isoflurane group, as compared to control; the results were reversed after the TLR4 interference. The hippocampal neurons in the isoflurane and siRNA-NC groups showed arrangement disorder and a high number of inflammatory infiltrates, while in the TLR-siRNA group they were closely and orderly arranged. Compared with the control group, the apoptosis rate and JNK protein expression in the isoflurane group were significantly increased, CREB1 protein expression was significantly decreased, and BDNF and ERK1/2 protein expressions showed no significant changes. Compared with the isoflurane group, the apoptosis rate of the TLR-siRNA group was significantly decreased, BDNF and CREB1 protein expressions were significantly increased, and ERK1/2 and JNK did not change significantly.

Conclusions. Isoflurane stimulates the overexpression of inflammatory response factors, playing an important role in the cognitive impairment process. As a mediator of the innate immune inflammatory response, TLR4 plays an important role in the process of cell injury, which may be delayed by blocking the TLR4 signal.

Key words: TLR4, isoflurane, memory function

Background

Early anesthetic exposure has been strongly linked to learning/behavior impairments in later life.1, 2, 3 Multiple exposures before the age of 3 are related to a higher rate of learning difficulties and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 Animal models confirmed long-lasting learning and memory impairments upon early postnatal exposure to anesthetics.4, 5, 6 Evidence showed that general anesthesia can promote apoptosis and cognitive impairment in the developing brain by exacerbating neuroinflammation.7

Isoflurane is a commonly used general anesthesia. Aseptic trauma of surgery can trigger an inflammatory cascade via the innate immune system, affecting synaptic plasticity in brain areas responsible for learning and memory.8 Besides, a previous study revealed that brief exposure to isoflurane can significantly induce inflammation in children without surgical stress.9

The hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) play an important role in learning and memory processes, including fear conditioning and processing of safety–threat information.10, 11, 12 The hippocampus and prefrontal areas have a key function in inhibitory control.13, 14 Isoflurane inhalation can induce hippocampal neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction in rats.15, 16 Isoflurane inhalation in children may produce neurodegenerative toxic effect17 and induce hippocampal apoptosis,15, 18 and its prolonged use in early life is considered to be closely related to cognitive impairment in later life.19 Isoflurane induced persistent and progressive decrease in hippocampal neural stem cell pool and neurogenesis in the developing brain of young rodents, with significant object recognition and reversal learning impairment which became more obvious as they grew older, whereas similar findings were not observed in adult rodents.20

Isoflurane anesthesia can alter the hippocampal dendritic spine morphology and development in neonatal mice.21 The exposure of immature neurons to isoflurane can also induce a long-term loss of synaptic connections.22 Isoflurane may have neurosynaptic toxic effects, thereby affecting synaptic plasticity and impairing learning and memory functions.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of pattern recognition receptors expressed on the membrane of the microglia. The TLRs can recognize pathogens and a variety of harmful substances produced in the body.23 The activation of microglia produces a corresponding response. In the TLR family, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is considered to be most closely related to the noninfectious inflammation in the brain.24 Experimental results show that TLR4 has a significant impact on the outcome of noninfectious central nervous system diseases, such as cerebral ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).25, 26 The alterations of the relevant neural structures may affect learning and memory processes.27 The inflammatory mediators released by the primary innate immune cells of the brain can compromise the neuronal structure and function, thus playing important roles in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases.28, 29, 30

Objectives

This study analyzed the function of TLR pathway in the learning and memory impairment in young mice caused by isoflurane. The TLR4-small interfering RNA (siRNA) was injected into the lateral ventricle of the brain31 to observe whether TLR4-siRNA intervention can alleviate the effects of isoflurane on impaired learning and memory function in young mice, which were assessed using Morris water maze test and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, in order to provide a feasible method for protecting the cognitive development of children undergoing surgery with isoflurane anesthesia.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

All experiments in this study has been approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jiangxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Nanchang, China, and conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of the Committee.

Experimental animals

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) grade, C57 mice (license No. SCXK (Xiang) 2016-002) were purchased from Hunan SJA Lab Animal Co., Ltd. (Hunan, China). The mice were raised in polypropylene cages, maintained at 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle, at a temperature of 25 ±2°C, and allowed food and water ad libitum.

Laboratory reagents and instruments

Main reagents

The reagents used in the study included: isoflurane (national drug approval No. H20070172; Shanghai Hengrui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); TLR4-siRNA oligos set (cat. No. i548002; Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, Canada); TRIzon reagent (CW0580S), ultrapure RNA extraction kit (CW0581M), HiFiScript first strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis kit (CW2569M), UltraSYBR Mixture (CW0957M), bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (CW0014S) (Beijing ComWin Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (IPVH00010; EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, USA); marker (PageRuler™ Prestained Protein Ladder; #26617), super enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) plus (RJ239676; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA); mouse monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 1/2000, TA-08), goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H+L) horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate secondary antibody (1/5000, ZB-2301; ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China); rabbit anti-TLR4 polyclonal antibody (1/1000, bs-20594R), rabbit anti-interleukin (IL)-6 polyclonal antibody (1/500, bs-6309R; Bioss Antibodies Inc., Woburn, USA); rabbit anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) polyclonal antibody (1/500, AF7014; Affinity Biosciences, Cincinnati, USA); rabbit anti-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (1/1000, ab108319; Abcam, Cambridge, USA); rabbit anti-cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein 1 (CREB1, 1/1000, 12208-1-ap), rabbit anti-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2, 1/1000, 16443-1-ap; Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, USA); rabbit anti-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK, 1/1000, df6089; Affinity Biosciences); terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (C1088; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China); mouse TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MM-0132M1), mouse IL-6 kit (MM-0163M1; Jiangsu Meimian Industrial Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China); radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (C1053), skimmed milk powder (P1622; Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China); and bovine serum albumin (BSA, A8020; Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China).

Main instruments

The instruments used in the study included: small animal ventilator (DW-3000C; Beijing Zhongshidichuang Science and Technology Development Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); isoflurane anesthesia ventilator (ABM-100), stereotaxic apparatus (SA-102), Morris water maze (JLBehv-MWMG; Shanghai Yuyan Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); fluorescence microscope (CX41; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan); microtome (BQ-318D; Bona Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Hubei, China); fluorescence quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) machine (CFX Connect™ Real-Time), ultra-high sensitivity chemiluminescence imaging system (Chemi Doc™ XRS+; Bio-Rad Laboratories Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); vertical protein electrophoresis system (DYY-6C), automatic microplate reader (WD-2102B; Beijing Liuyi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); low-temperature high-speed centrifuge (5424R; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany); and constant temperature shaker (TC-100B; Shanghai Tocan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Allocation sequence and blinding

Allocation sequence was performed using random numbers generated by a computer. The researchers conducting the experiments, the outcome assessment and the data analysis were blinded to the group allocation.

Sample allocation

First, the adult mice were caged together with female/male ratio of 2:1. Then, the newborn mice were randomly allocated into 4 groups. There was no requirement for gender of the young mice and it was ensured that there were 12 in each group, 6 of which were randomly allocated for qRT-PCR and western blot (WB) analysis. The hippocampal tissue was taken and evenly divided into 2 parts from the midline, one part was used for qPCR and the other for WB analysis. Another 3 mice from each group were used for H&E staining and serum collection for ELISA test. The brain tissue was obtained, placed in 10% formalin and stored at 4°C for H&E staining. The remaining 3 mice from each group were taken for the water maze experiments.

Experimental grouping

The newborn mice were randomly assigned into 4 groups as follows:

(1) Normal control group (control): no isoflurane anesthesia was given;

(2) Isoflurane anesthesia group (isoflurane): the mice were given isoflurane anesthesia;

(3) TLR4 interference empty vector+isoflurane anesthesia group (siRNA-NC): the mice were given intracerebroventricular injection of TLR4 interference negative control plasmid (2 μL, 50 μM/L), followed by isoflurane anesthesia;

(4) TLR4 interference+isoflurane anesthesia group (TLR-siRNA): the mice were given intracerebroventricular injection of TLR4 interference plasmid (2 μL, 50 μM/L), followed by isoflurane anesthesia.

Isoflurane anesthesia was given by inhalation with 3% isoflurane + 60% O2 induction for the first 3 min, at a flow rate of 2 L/min, followed by maintenance at a flow rate of 1 L/min for 3 h, for 3 consecutive days.

For groups (3) and (4), after 5 days of intracerebroventricular injection (injection into the lateral ventricle of the brain) (6-day-old mice), isoflurane inhalation was given for 3 h for 3 consecutive days (6-day, 7-day and 8-day-old mice).

Mice behavior detected

using Morris water maze test

When the mice reached 31 days of age, 3 mice from each group were taken for water maze experiment to observe the changes in animal behavior. The procedures were as follows:

1) Place navigation: The mice memory and learning abilities in the water maze were assessed. One day before the experiment, the mice were placed in the water maze for 60 s to adapt to the environment. The mice were trained for 4 consecutive days, 4 times per day in the afternoon, with an interval of 15 min between each time. In each experiment, one mouse was placed in the pool with the head facing the side wall in 4 different directions (1 of the 4 directions each time). The order was different each day. The mice were allowed to swim until they found a platform and stayed on it for 20 s to achieve the effect of memory enhancement. The route to the platform that the mice were searching for under the water and the escape latency (the time it took to get from the water to the platform) were noted and recorded by a camera. If the mice did not reach the platform within 60 s, the escape latency was recorded as 60 s, and they were guided by the investigator to the platform and stayed on it for 30 s. The markers around the water maze were fixed, with no sound, no light and no human interference.

2) Spatial probe: It was used to detect the mice ability to remember the spatial position of the platform after learning to find it. The spatial probe test was carried out on the 5th day, following 4 days of training. The platform was removed. The mice were placed in the water on the opposite side of the original platform quadrant. The time the mice spent in the target quadrant and other quadrants was recorded.

Pathological condition in the hippocampal tissue detected with H&E staining

The mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Under aseptic condition, the brain tissue was removed and washed with running water for several hours. The tissues were dehydrated with 70%, 80% and 90% ethanol solutions, and immersed in an equal amount of pure alcohol and xylene for 15 min, followed by xylene I and II (15 min each, until clear). Subsequently, the tissues were placed in an equal amount of xylene and paraffin for 15 min, followed by paraffin I for 50–60 min and paraffin II for another 50–60 min. The tissues were embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned, baked, dewaxed, and hydrated. The sections were placed in distilled water, and then subjected to hematoxylin staining for 3 min. Then, the sections were differentiated with hydrochloric acid ethanol for 15 s, and slightly washed with water. Blueing was performed for 15 s, and the sections were washed with running water, subjected to eosin staining for 3 min, and then again washed with running water. Then, they were dehydrated, cleared, mounted, and viewed under the microscope.

TLR4, BDNF and CREB1 mRNA expressions in the hippocampal tissue detected with fluorescence qPCR

Following RNA extraction, cDNA was synthesized using the reverse transcription kit. With cDNA as the template, the detection was performed with the fluorescent qPCR machine. The expression of TLR4 in each group was estimated using GAPDH as the internal reference.

The operating system, reaction procedure and melting curve analyses were presented in Table 1A–C. The primer information was displayed in Table 2.

TLR4, TNF-α, IL-6, BDNF, CREB1, ERK1/2, and JNK protein expressions in the hippocampal tissues detected with western blot

The samples in each group were added with lysis buffer, put on ice for 30 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully aspirated for total protein determination. The protein content was measured using the BCA kit. The protein was denatured, and sample loading was performed. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel electrophoresis was conducted for 1–2 h, followed by wet transfer for 30–50 min. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by the secondary antibody for 1–2 h at room temperature. The ECL solution was applied onto the membrane and the image was captured under the gel imaging system. The gray value of each antibody band was determined using the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Co., Ltd.).

Serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels

detected using ELISA

First, all reagents and components were brought back to room temperature. The standards, quality control products and samples were prepared in replicates. The working solution of various components of the kit were prepared according to the kit manual. The aluminum foil bags containing the ELISA-coated plates were removed. The standard and sample wells were established. Each of the standard wells received 50 μL of standards at various concentrations. The blank control wells were not added with samples or enzyme-labeled reagents; the remainder of the procedures were the same as the sample wells. Each sample well received 40 μL of sample diluent, followed by 10 μL of sample (the final dilution of sample was ×5). The samples were placed at the bottom of the wells, avoiding touching the side walls. They were gently shaken and mixed. Except for the blank control wells, each well received 100 μL of enzyme-labeled reagent. The plate was sealed with a film, which was then incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Before use, the wash buffer concentrate (×20) was diluted 20 times with distilled water. The sealing film was removed with care, and the liquid was patted dry. Each well was filled with wash buffer, left for 30 s and then discarded. This was performed 5 times, and each well was patted dry. Then, color reagents A and B (each 50 μL) were added into each well, gently shaken and mixed. Color was developed for 15 min at 37°C in the dark. The reaction was then terminated by adding 50 μL of stop solution to each well. The color was changed from blue to yellow. The blank well was adjusted to zero, and the absorbance (optical density (OD) value) of each well was measured at 450 nm.

Apoptosis rate in the hippocampal tissue detected with TUNEL staining

The tissue sections were placed in oven at 65°C and baked for 2 h. The sections were immersed in xylene for 10 min. Then, the xylene was replaced with fresh xylene and the sections were left for another 10 min. The sections were put in 100% (twice), 95% and 80% ethanol, and then purified water, for 5 min each. The sections were placed in a wet box and 50 μg/mL proteinase K working solution was applied dropwise to each sample and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Then, the sections were washed thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min 3 times. The PBS around the tissue was absorbed with absorbent paper, an appropriate amount of TUNEL detection solution was added to each slide, and the sections were incubated in the dark for 2 h at 45°C. The slides were then washed with PBS for 5 min 3 times. The liquid on the glass slide was absorbed with absorbent paper. The glass slides were mounted with antifade mounting medium and examined with a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analyses

The IBM SPSS v. 19 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) was used for data analysis. The measurement data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (x ±SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for the comparisons between the groups. Post hoc test was performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. The value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome: The behavior of mice treated with TLR4-siRNA compared with the control, isoflurane and siRNA-NC groups.

Secondary outcomes: The pathological condition, TLR4, BDNF and CREB1 mRNA expressions, serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels, apoptosis rate, and TLR4, IL-6, TNF-α, BDNF, CREB1, ERK1/2, and JNK protein expressions in mice treated with TLR4-siRNA, compared with the control, isoflurane and siRNA-NC groups.

Results

Mice behavior detected

using Morris water maze test

As demonstrated in Figure 1 (and Supplementary Table 1), the number of times the mice in the isoflurane group crossed the platform was significantly smaller, and the time spent at the platform circumjacent area I and II for the spatial probe test was significantly shorter than in the control group (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.001, respectively), while these values were significantly higher in the TLR-siRNA group than in the isoflurane group (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.001, p = 0.009, p = 0.007, respectively).

Pathological condition in the hippocampal tissue detected with H&E staining

The results of the pathological staining in each group were shown in Figure 2. The neurons in each area of the hippocampus in the control group were closely arranged, the cell body size was normal, no obvious edema and degeneration were noted, and the inflammatory cell infiltration was relatively low. Both the isoflurane group and the siRNA-NC group had varying degrees of neuron arrangement disorder as well as a large number of inflammatory infiltrates. The neurons in the TLR-siRNA group were arranged in a relatively close and orderly manner.

TLR4, TNF-α and IL-6 expressions in the hippocampal tissue detected with qPCR and WB

As shown in Figure 3 (and Supplementary Table 2), the TLR4, TNF-α and IL-6 expressions in the isoflurane group were significantly increased compared with the control group (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.001 for TLR4 mRNA expression, all p < 0.001 for protein expressions), while in the TLR-siRNA group they were significantly decreased when compared with the isoflurane group (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.004 for TLR4 mRNA expression, all p < 0.001 for protein expressions).

Serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels

detected with ELISA

As presented in Figure 4 (and Supplementary Table 3), the TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the isoflurane group were significantly increased compared with the control group (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.001 both), while in the TLR-siRNA group they were significantly decreased when compared with the isoflurane group (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.001 both).

Apoptosis rate in the hippocampal tissue detected with TUNEL staining

As shown in Figure 5 (and Supplementary Table 4), the apoptosis rate in the isoflurane group was significantly increased compared with the control group (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.005), while in the TLR-siRNA group it was significantly decreased when compared with the isoflurane group (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.004).

BDNF and CREB1 mRNA expressions in the hippocampal tissue detected with qPCR

As revealed in Figure 6 (and Supplementary Table 5), the BDNF mRNA expression in the isoflurane group was increased (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.898), and the CREB1 mRNA expression was decreased when compared with the control group (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.654). The BDNF mRNA expression in the TLR-siRNA group was decreased (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.660) and the CREB1 mRNA expression was significantly decreased (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.013) compared with the isoflurane group.

BDNF, CREB1, ERK1/2, and JNK protein expressions in the hippocampal tissue detected with WB

As shown in Figure 7 (and Supplementary Table 6), the CREB1 protein expression in the isoflurane group was significantly decreased (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.018) and the JNK protein expression was significantly increased (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.004), while the BDNF and ERK1/2 protein expressions did not show significant changes (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.317, p = 0.789, respectively) compared with the control group. The BDNF and CREB1 protein expressions in the TLR-siRNA group were significantly increased (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.001, both), while the ERK1/2 and JNK protein expressions did not show significant changes (Tukey’s HSD; p = 0.994, p = 0.547, respectively) when compared with the isoflurane group.

Discussion

A number of studies have found that the inhalation of anesthetics may cause or increase the risk of cognitive impairment in humans and rodents.32, 33 A large number of animal experiments have shown that the current clinical use of inhaled and intravenous general anesthetics can cause obvious and extensive apoptosis of the developing neurons, and cognitive impairment and abnormal function of neural circuit, as well as decline or loss of cognitive behavior ability in adulthood.4, 34, 35

The TLR4 is an important part of the activation of the innate immune system, and is expressed in neurons and glial cells.36 It does not only mediate the innate immune response, but also participates in the inflammatory reactions and neurodegeneration.37, 38 In this study, the number of times the mice crossed the platform, and the time they spent at the platform circumjacent area I and II for the spatial probe test were significantly decreased in the isoflurane group, indicating that isoflurane can impair the cognitive and behavioral abilities of the mice. The cognitive ability recovered after the TLR4 interference. These findings indicate that the TLR4 expression plays an important role in the cognitive ability of mice.

The TLR4 activation can lead to a substantial number of neuronal deaths.39 Studies have found that an increased expression of TLR4 aggravates the increase of the inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus, which may further stimulate the neuroinflammatory response by activating microglia and astrocytes, and eventually lead to neuronal damage and cognitive decline.40 In this study, basing on the H&E staining results, it could be observed that the hippocampal neurons in the control group were closely arranged, and inflammatory cell infiltration was relatively low, whereas the isoflurane and siRNA-NC groups showed varying degrees of neuron arrangement disorder and a high number of inflammatory infiltrates. The neurons in the TLR-siRNA group were arranged in a relatively close and orderly manner.

The increase of peripheral inflammatory cytokines can cause cognitive impairment. At present, more than 30 kinds of cytokines are known, including interleukins (IL-1 to IL-4), TNF and transforming growth factor (TGFβ1-3), among which IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α are considered to be the typical pro-inflammatory cytokines.41 The IL-1, produced by the activation of microglia, is the initiating link of the inflammatory response. The IL-1 promotes the proliferation and activation of microglia through the autocrine pathway, initiates the release of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and induces the increase in the production of complement and chemokines. In turn, the immune inflammatory cytokines activate microglia, resulting in a continuous increase in cytokines that eventually lead to neuronal degeneration and necrosis, which further stimulates microglia to synthesize and secrete cytokines, and forms a positive feedback loop in the body, resulting in a cascade amplification effect of inflammatory response.42, 43 The TLR4 can promote expressions of the inflammatory factors such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α. At the same time, these inflammatory factors interact with each other, causing an excessive release of inflammatory mediators, which further aggravate tissue and organ damage.44 The results of this study revealed that the expressions of the inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 increased significantly after the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and decreased significantly following the TLR4 expression interference. These results indicated that TLR4, as an innate immune inflammatory response mediator, may mediate the excessive release of the inflammatory response factors, causing nerve cell damage, and long-term excessive damage may lead to a decline in the cognitive function.

In addition, we found that isoflurane anesthesia significantly increased the apoptosis rate of the hippocampal tissue. The apoptosis rate in the TLR-siRNA group was significantly decreased compared with the isoflurane group. Further mechanism study demonstrated that the CREB1 protein expression in the isoflurane group was significantly decreased, and the JNK protein expression was significantly increased compared with the control group; however, the protein expressions of BDNF and ERK1/2 did not show any significant changes. The BDNF and CREB1 protein expressions in the TLR-siRNA group were significantly increased, while the ERK1/2 and JNK protein expressions did not show any significant changes compared with the isoflurane group.

Generalizability of the study

The findings of this study can be generalized to human and validated by further clinical trials.

Limitations

First, this study only shows the protective effect of TLR4-siRNA intervention on learning and memory function of young mice induced by anesthetics, but the mechanism of TLR4 is not clear. Second, surgical anesthesia involves a broad array of drugs. This study only explores the effect of isoflurane anesthesia, which is not comprehensive enough. A variety of anesthetic agents can be explored to illustrate the universality of the role of TLR4 in cognitive impairment.

Future research can be extended in 2 directions. First, to explore the mechanism of TLR4 in microglia at the cellular level. Second, to establish a model of postoperative cognitive impairment induced by a variety of anesthetics to prove the universality of the role of TLR4.

Another limitation is the small sample size of the study; the homogeneity of variance and normality were assumed without checking the assumptions. Future research should involve a larger size sample.

Conclusions

The exposure to isoflurane anesthesia plays a crucial role in the cognitive impairment process in young mice. Isoflurane anesthesia stimulates the inflammatory response factors to overexpress, causing neuronal cell damage and eventually cognitive impairment. An early exposure to isoflurane anesthesia can lead to a persistent impairment in memory and learning function of the developing brain. As a mediator of the innate immune inflammatory response, TLR4 plays a key role in the cell injury process. Blocking TLR4 signal may delay the process of cell inflammatory injury and cognitive impairment.

Supplementary data

Additional data showing the exact statistical analysis data have been deposited at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6319656.

The package contains 6 files:

Supplementary Table 1. Morris water maze test results of each group;

Supplementary Table 2. TLR4, TNF-α and IL-6 expressions in the hippocampus of each group detected with qPCR and WB;

Supplementary Table 3. Serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels of mice in each group detected with ELISA;

Supplementary Table 4. Apoptosis rate detected with TUNEL staining;

Supplementary Table 5. BDNF and CREB1 mRNA expressions detected with qPCR;

Supplementary Table 6. BDNF, CREB1, ERK1/2, and JNK protein expressions detected with WB.