Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is one of the most commonly diagnosed blood cancers. One criterion for the diagnosis of MM is serum and/or urine monoclonal protein produced by clonal plasmocytes. However, about 1–2% of MM cases do not have monoclonal protein. If other diagnostic criteria are present, the possibility of a diagnosis of non-secretory MM should be considered. As the different types of non-secretory MM depend on the underlying cause, the current definition is considered insufficient. Currently, both the diagnosis and treatment of non-secretory MM are the same as those of secretory MM. Due to the rarity of non-secretory MM, most findings are from retrospective studies on small groups of patients and case reports. The method of monitoring the effectiveness of MM treatment remains a problem, as it is usually based on the assessment of the percentage of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow and imaging studies.

Key words: diagnosis, management, non-secretory multiple myeloma

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a blood cancer that arises from clonal plasmocytes (CP) that accumulate in the bone marrow (BM) and, in most cases, produce monoclonal (M) protein. Infiltration of CP may occur at extramedullary sites and/or in peripheral blood during disease progression.1 Multiple myeloma is the 2nd most frequently diagnosed hematologic malignancy and accounts for 10–15% of all blood cancers and 1–1.8% of all cancers. The incidence of MM in Europe is 4.5–6.0/100,000/year.2 According to the National Health Fund (Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia (NFZ)) data, there were nearly 2600 new MM cases in Poland in 2016.3 The median age at MM diagnosis is 72 years.2 Over 90% of patients are >50 years old at MM diagnosis, while only 2% of patients are younger than 40 years.4 Currently, the median overall survival (OS) of MM patients is approx. 6 years.5 In the subgroup of patients treated with high-dose (HD) chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), the median OS is approx. 8 years.6 In comparison, it is shorter in the subgroup of patients >75 years of age and amounts to approx. 5 years.5 In 2014, the criteria for the diagnosis of MM were modified (Table 1).7 One of the primary criteria for the diagnosis of MM are CP that produce M-protein. This is typically M-protein of the immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgA or free light chains (FLCs) of the kappa or lambda type, which account for 54%, 21% and 16% of all MM cases, respectively.8 Monoclonal IgD protein is found in less than 2% of MM patients. Notably, M-protein is not present in serum or urine in approx. 3–5% of patients meeting the criteria for MM diagnosis.9 These types of MM are generally referred to as non-secretory (NS) MM. The introduction of serum FLC (sFLC) as part of laboratory diagnostics has confirmed both, the prevalence and change in the definition of NSMM. Currently, it is believed that approx. 2% of MM patients are diagnosed with true NSMM in which M-protein is not found by standard testing.10

Objectives

This article aims to present the current terminology and principles of diagnosis and treatment of patients with NSMM.

Methodology

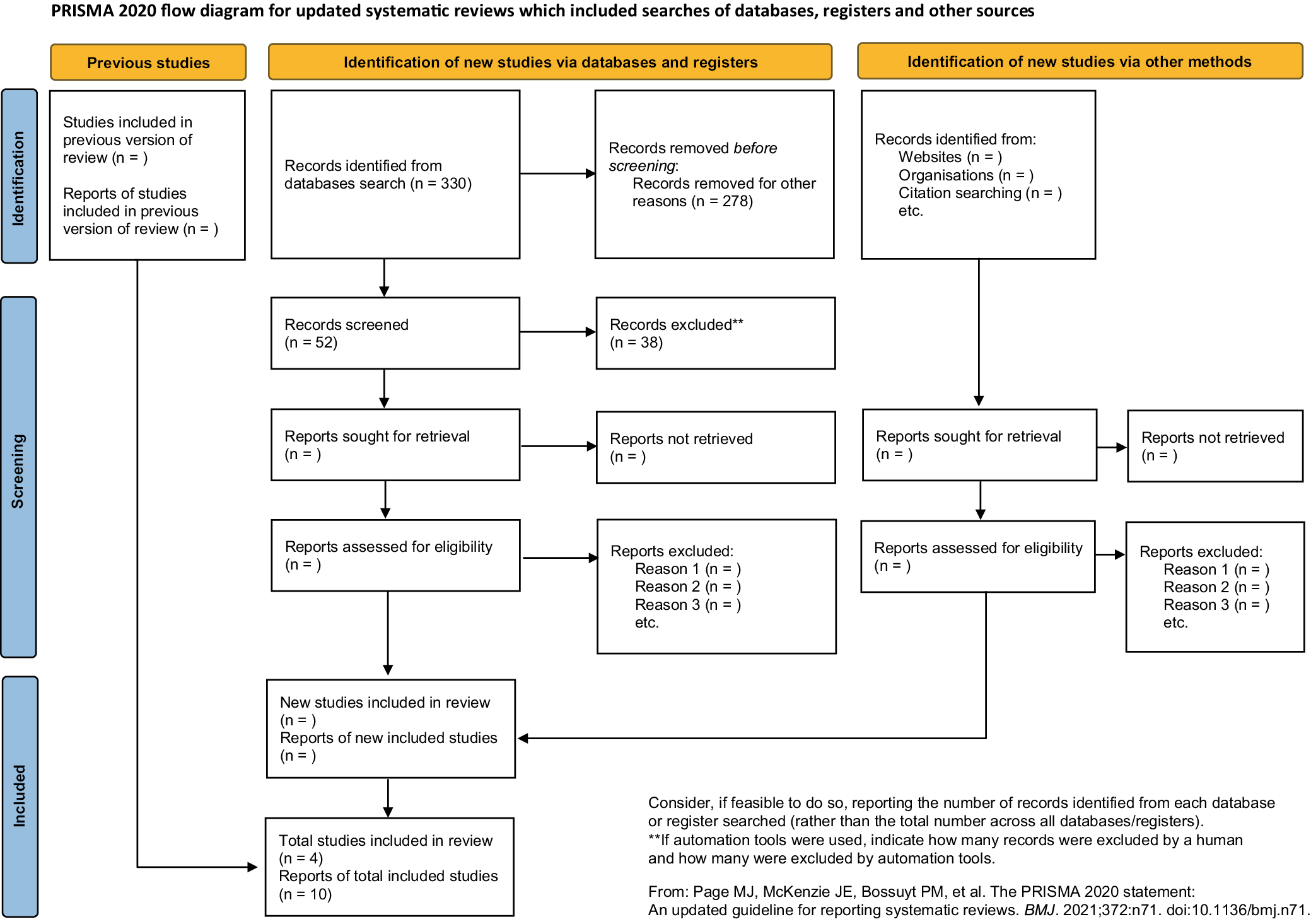

Data on the diagnosis and treatment of NSMM presented in this article are based on published studies available in the PubMed online database. Based on selected key words, we identified 358 articles related to NSMM. After reviewing them, 52 full papers were included, 14 of which are included in this article. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented as Figure 1.

Mechanisms of monoclonal protein production

The M-protein found in the serum and/or urine of patients with MM may take the following forms11:

1. high concentration of whole Ig molecules composed of heavy and light chains;

2. high concentration of whole Ig molecules with an additional high concentration of light chains not associated with heavy chains;

3. free light chains in the presence of very little or even no total Ig; and

4. free heavy chains in the absence of associated light chains.

The reasons for the inhibition of M-protein production, or secretion by CP, are not fully understood. One cause of true NSMM is the loss of the ability of CP to initially secrete heavy chains and then light chains of Ig.12 Other possible causes and hypotheses include: the loss of the polyadenylation site necessary for extracellular Ig secretion13; loss of the heavy chain V domain, which leads to the decreased secretion and increased intracellular Ig destruction14; loss of the ability to produce M-protein due to the mutation of the Ig light chain14; the secretion of heavy chains (which are considered toxic to plasmocytes) by plasmocytes which may promote their survival during clonal evolution in MM.15

Types of NSMM

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) defines NSMM as MM in the absence of M-protein in the serum and/or urine protein immunofixation assay.7, 16 Thus, this definition does not include MM with light chains only detected with the sFLC assay.9, 17 For this reason, the current definition is insufficient. As CP secretes the Ig component, cases of NSMM can be further classified into at least 2 distinct categories with subcategories18:

1. non-secretory MMs (85% of cases):

• oligo-secretory/FLC-restricted MMs: in most cases, the light chains are detected using the sFLC assay. In cases of oligo-secretory MM, serum M-protein <1.0 g/dL, urine M-protein <200 mg/24 h and sFLC values <100 mg/L are common;

• true NSMMs: CP produces M-protein, but is unable to secrete it into the extracellular space;

• false NSMMs: the immunofluorescence test shows the presence of M-protein inside CP, but no extracellular M-protein is found using standard laboratory tests;

2. non-producing MMs (15% of cases): no Ig production by CP is found.

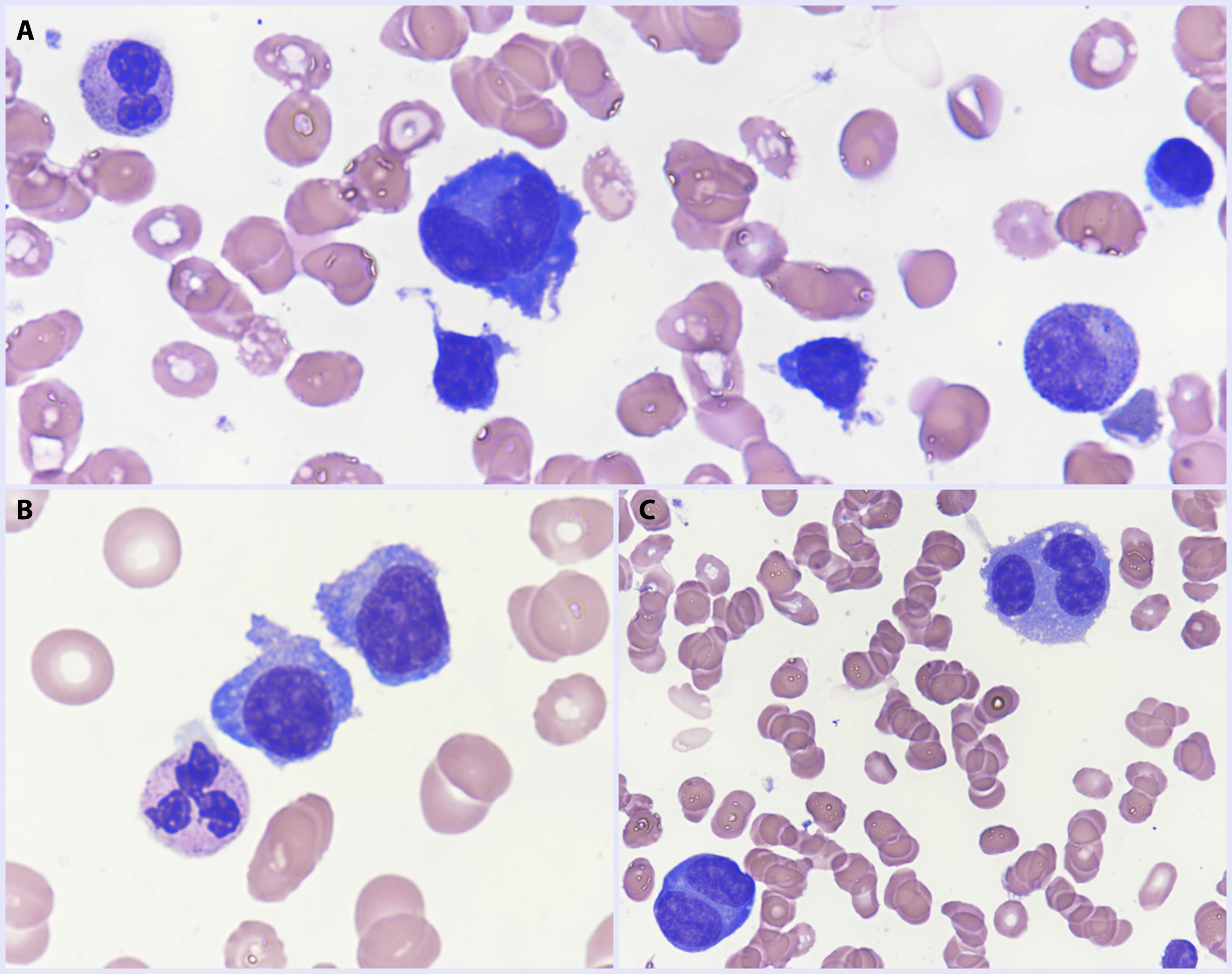

Figure 2 shows the infiltration of CP in the BM of a patient with NSMM.

Diagnosis and monitoring of NSMM

The diagnostic tests recommended for patients with suspected NSMM are the same as those recommended for patients with secreting MM. Besides diagnosing NSMM, one purpose of these tests is to identify the presence of symptoms of end organ damage, such as hypercalcemia, anemia or bone damage, to distinguish asymptomatic from symptomatic cases.16 Initial laboratory investigation for NSMM should include complete blood count (CBC), serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE), sFLC assay, and quantitative Ig levels including IgD and IgE. Urinalysis for initial workup should include a 24-hour urine test with protein quantification and IFE. In addition, a baseline metabolic panel should be performed to assess coagulation factors, renal and liver function, serum calcium level, β-2-microglobulin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). All patients with suspected NSMM require a BM biopsy for cytology, histopathology, multiparameter flow cytometry (MPF) and CD138 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The most frequently observed primary cytogenetic abnormality in NSMM patients is t(11,14) (q13,q32), which occurs in about 60–80% of patients with NSMM.19, 20 Table 2 lists the diagnostic tests recommended for patients with suspected or diagnosed NSMM. Figure 3 shows the diagnostic algorithm for NSMM.

If true NSMM is suspected, staining should be performed to assess the intracellular presence of Ig. True cases of NSMM typically lack easy parameters for evaluating treatment efficacy. For this reason, sensitive skeletal examinations, including positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT), are recommended. It is thought that by performing PET/CT together with BM examination, the effectiveness of the applied NSMM treatment can be objectively assessed.21 In general, monitoring the response of NSMM treatment is a challenge for both, hematologists and oncologists. The abovementioned methods are currently considered the “gold standard” for monitoring responses in all MM types, including BM aspiration in NSMM cases and MM tumor biopsy. The primary method used to monitor treatment response in patients with oligosecretory MM is the sFLC assay. A more sensitive test used to assess BM cells, including CP, is MPF.22 Simultaneous BM examination with MPF and sensitive imaging (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or PET/CT) is currently the best way to assess the effectiveness of treatment in patients with NSMM.23, 24

During induction treatment of patients with NSMM, it is recommended to repeat BM biopsy every 3–6 months and whole body PET/CT examination every 6–12 weeks, especially for cases of true NSMM. For patients who achieve remission after treatment or during maintenance treatment, it is recommended to repeat BM biopsy and PET/CT scan every 3–6 months.25

Treatment of NSMM

Considering the rarity of NSMM and the ineligibility of patients with NSMM for clinical trials, its clinical course and prognosis are not fully known. We do not have conclusive data to suggest that the efficacy of NSMM treatment differs from that of secreting MM. The literature is dominated by case reports and retrospective analyses of small groups of NSMM patients. In 2020, PubMed published 8 case reports and 1 retrospective treatment analysis of patients with NSMM. Retrospective studies investigated standard treatments for NSMM patients with conventional chemotherapy and HD chemotherapy followed by ASCT. In one of the largest retrospective studies, Chawla et al. examined the survival and prognosis of 124 patients with NSMM. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 28.6 months and the median OS was 49.3 months. Investigators found that the time to progression, PFS, and OS before 2001 were all comparable to those for patients with secretory MM.26 There has been a significant improvement in patient outcomes: median survival was 43.8 months before 2001 compared to 99.2 months for 2001–2012 (p < 0.001). For patients diagnosed in the period of 2001–2012, OS was better in NSMM cases than in secretory MM cases (median survival of 8.3 years vs 5.4 years, p = 0.03). There were no survival differences in patients treated with HD chemotherapy followed by ASCT.26 In a study by Kumar et al., of 110 patients with NSMM treated with ASCT, the median PFS and OS were 30 months and 69 months, respectively. Three-year PFS in NSMM and secretory MM cases was 40% and 33%, respectively (p = 0.05), while three-year OS was 66% and 61%, respectively (p = 0.26).27 Due to the higher occurrence of t(11,14) in NSMM, a change in treatment is expected in the near future. Studies by Smith et al.28 and Terpos et al.29 found longer survival times (PFS, OS) in patients with NSMM. The results of selected retrospective studies of patients with NSMM are presented in Table 3.

Conclusions

Non-secretory MM is a rare type of MM. We lack data to determine the prevalence of NSMM in Poland. Extrapolating data obtained from other countries, we can expect approx. 25–50 new NSMM cases per year in Poland.

Given the subtypes and pathogenesis of NSMM, the definition of this form of MM is likely to change in the near future. Due to the difficulties in assessing the effectiveness of treatment, patients with NSMM usually do not qualify for prospective clinical trials. As a result, the available data are typically the results of retrospective studies or case reports. Currently, treatments for NSMM are the same as those for secretory MM. Given the higher incidence of t(11,14), we may soon see a change in the treatment for this subgroup of MM. There is undoubtedly a need for more research into this rare type of MM.