Abstract

Background. Capsules are solid drug forms that are well accepted by patients. Capsules usually consist of a medicinal substance with therapeutic benefits plus excipients. From a pharmaceutical point of view, DNA coding sequences can be treated as active substances.

Objectives. To develop and assess gelatin capsules containing DNA based on the methods included in the Polish Pharmacopoeia XI, as well as non-pharmacopeial methods.

Materials and methods. The mass uniformity of the obtained capsules was estimated. The stability of the DNA was verified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. A study of the disintegration time of the gene capsules containing DNA mixed with lactose, and placebo capsules with lactose only was also performed. A dissolution test under conditions similar to the nature and specificity of the active substance (DNA) was performed. The transduction activity of the obtained capsules was assessed in cell culture conditions.

Results. The DNA and lactose-based gene capsules were obtained. The capsules were characterized by mass uniformity and stability over time. Efficient transduction of B16-F10 cancer cells with the gene product from the capsule was observed using fluorescence microscopy. Groups of green fluorescent protein-positive cells were observed in the microscope field of view.

Conclusions. The findings showed that it is possible to obtain a solid pharmaceutical form of the drug, i.e., a capsule containing DNA as an active substance. The gene capsules enabled the introduction of DNA into cells. This method may have valuable implications for increasing the availability of gene-based drugs for patients.

Key words: drug delivery, gene therapy, gene capsules, applied pharmacy

Background

Capsules are a well-known solid dosage form of drug administration. According to the definition of Polish Pharmacopoeia XI (Ph Pol XI), capsules are solid formulations that have the form of a reservoir of various shapes and sizes, usually containing a single dose of active ingredient(s).1 Solid oral dosage forms, such as tablets and capsules, are generally the preferred method of drug delivery due to their comfort of use, low cost and high patient acceptability.2 Capsules are used to administer drugs to patients suffering from various diseases, and therefore they play an important role in delivering diverse drugs.3 Studies of patients’ preferred dosage form found that more than half of patients (52.9%) prefer a capsule, 28.4% prefer a coated tablet, 12.7% prefer an uncoated tablet, and 3.5% prefer a soft-gel capsule. Preferences regarding capsules were significantly associated with the easiest way of swallowing this drug form.4 One of the many advantages of capsules over tablets is the ability to deliver medicinal substances not only in a solid form, but also in nonaqueous liquid and semisolid substance forms.5, 6

Capsules are a form of a drug formed not only in industrial settings, but also directly in pharmacies. Pharmacists’ knowledge about the physicochemical properties of drugs and medicinal products is necessary for the preparation of the drug form.7 Drug prescribing is useful for practical pharmacy, since physicians do not have to be limited to the available industrial preparations. Then, the capsules can be prepared in a pharmacy, based on the physician’s prescription for an individual patient.3 Therefore, this form of drug delivery may be applicable for personalized therapy.8 Pharmacies have an educated personnel and specialized equipment for drug production. Consequently, they may play an important role in clinical trials.9 Capsules containing various active substances can be prepared at a pharmacy. Compared with tablets, capsules usually contain less excipients.10 It is well-documented that the composition can be limited to 1 excipient without its own pharmacological and adverse effects.1, 11 An example of a known excipient is lactose (saccharum lactis, β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1-4)-d-glucopyranose), which is often used in industry and in pharmaceutical formulations. It shows a tendency to crystallize when stored at a high relative humidity; however, it is stable and nontoxic. Moreover, lactose does not interact pharmaceutically and pharmacodynamically with other drug components and improves taste.12 Although preparation of capsules is well-established, the preparation of capsules containing genes is of great interest due to their potential use in gene therapy.

Gene therapy is a treatment method based on the use of nucleic acids as active substances. The proteins encoded by the selected gene sequences cause a therapeutic effect.13 Currently, gene preparations are administered to patients mainly in liquid form as an injection or infusion of solutions or suspensions. These preparations are then administered to patients intravenously, intramuscularly, intratumorally, intradermally, or subretinally (in ophthalmology).14 The literature has reported many experimental studies in the field of gene therapy for cancer, metabolic and infectious diseases, and correction of congenital disorders.15 Patients’ expectations are raised by gene preparations registered for treatment. Glybera, Luxturna and Zolgensma are used in the treatment of metabolic diseases, ophthalmic diseases and neurodegenerative disorder, respectively, and belong to the parenteral drugs.16 Glybera is a solution for intramuscular injection that contains the following excipients: disodium phosphate anhydrous, potassium chloride, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, sodium chloride, sucrose, and water for injection.17 Luxturna is a solution for subretinal injection. Before administration, it is prepared by diluting the concentrate with a solvent. Both solutions contain the same excipients: sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate and dihydrate, poloxamer 188, and water for injection.18 Zolgensma is intended for intravenous infusion and, in addition to the medicinal substance, contains tromethamine, magnesium chloride, sodium chloride, poloxamer 188, hydrochloric acid, and water for injection.19 Concepts of gene therapy based on oral drug forms are detailed in experimental studies. The literature describes the attempts to use microspheres, forms based on chitosan, modified silica, and modified micelles.20, 21, 22, 23 The plasmid encoding interleukin 10 (IL-10) incorporated in microspheres has been used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.20 Chitosan microparticles containing plasmid DNA have been developed.21 Oral gene delivery using poly-L-lysine modified silica nanoparticles has been attempted, and the ability of poly (allylamine) amphiphilic polymer micelles to deliver small interfering RNA (siRNA) through the gastrointestinal tract has been assessed.22, 23 The described examples of oral gene preparations emphasize the importance of this method in experimental studies in search for a new route of delivering gene therapy products. Achieving the therapeutic potential of DNA requires the development of new pharmaceutical formulations to enable a safe and effective administration of gene drugs.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to design gene capsules containing plasmid DNA (pDNA) or recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV). The capsule formulations were then characterized by appropriate pharmaceutical and biological tests to verify their stability and activity.

Materials and methods

Formulation and preparation

of gene capsules

Hard gelatin capsules (Eprus, Bielsko-Biała, Poland) containing genes were prepared. In accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations for capsule capacity, each capsule contained 0.18 g of lactose (pure lactose monohydrate; Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland) and 50 µg of the pAAV/LacZ plasmid (LacZ – β-galactosidase; Cat. No. 240071; Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) or 4 × 104 genome copies (gc) rAAV/GFP (rAAV/DJ-CAG-GFP; Cat. No.7078; Vector Biolabs, Malvern, USA). Placebo hard gelatin capsules containing only 0.18 g of lactose were also produced. The capsules with plasmid and placebo were made with a manual capsule filling machine (Eprus), while capsules with the viral vector were prepared by hand.

Size 3 hard gelatin capsules were prepared. For the placebo capsules, using an analytical balance, 18.0 g of lactose was weighed and then the powder was thoroughly ground in a mortar. The empty capsules were placed in the manual capsule filling machine using a positioner. The capsules were opened using the top plate of the capsule machine and the prepared powder mass was placed on the plate of the capsule machine. The powder mass was gently spread into the capsules. The capsules were then closed and removed from the capsule filling machine. Next, the gene capsules were prepared (Figure 1). On an analytical balance, 18.0 g of lactose was weighed and 1000 µL of 5 µg/µL pAAV/LacZ solution (50 µg of pDNA per capsule) was added and mixed gently. A larger amount of solution leads to overwetting of the excipient and to softening and deformation of the capsule, consequently reducing its stability. The 2nd group of gene capsules contained the rAAV vector encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. For this purpose, 0.18 g of lactose was weighed into each capsule and 4 × 104 gc of rAAV in 10 µL of water for injection was added.

The obtained capsules were then tested using the following pharmacopeial methods1: uniformity of single-dose preparations, examination of disintegration time, dissolution and stability tests, and transduction activity tests.

Mass uniformity

of single-dose preparations

The study was performed in 5 groups of 20 gene (Table 1) and 5 groups of 20 placebo capsules (Table 2), based on the Ph Pol XI.1 The capsules were weighed on an analytical balance.

Each capsule was first weighed. Next, the capsule was opened without losing any part of the casing, the contents were emptied as completely as possible and the casing was weighed. The weight of the contents is the difference between the weight of the filled and emptied capsule. According to Ph Pol XI,1 for capsules weighing less than 300 mg, the permissible deviation is ±10%. For 20 tested capsules, 2 may exceed the acceptable deviation, but not more than twice.

Capsule disintegration time

The disintegration time study was based on Ph Pol XI1 with some modifications due to the physicochemical properties of the active substance (DNA). According to the definition in Ph Pol XI, a complete disintegration is defined as the state where all remainders of the capsule are a soft mass without a compact, non-wetted core, except for fragments of undissolved capsule shell.

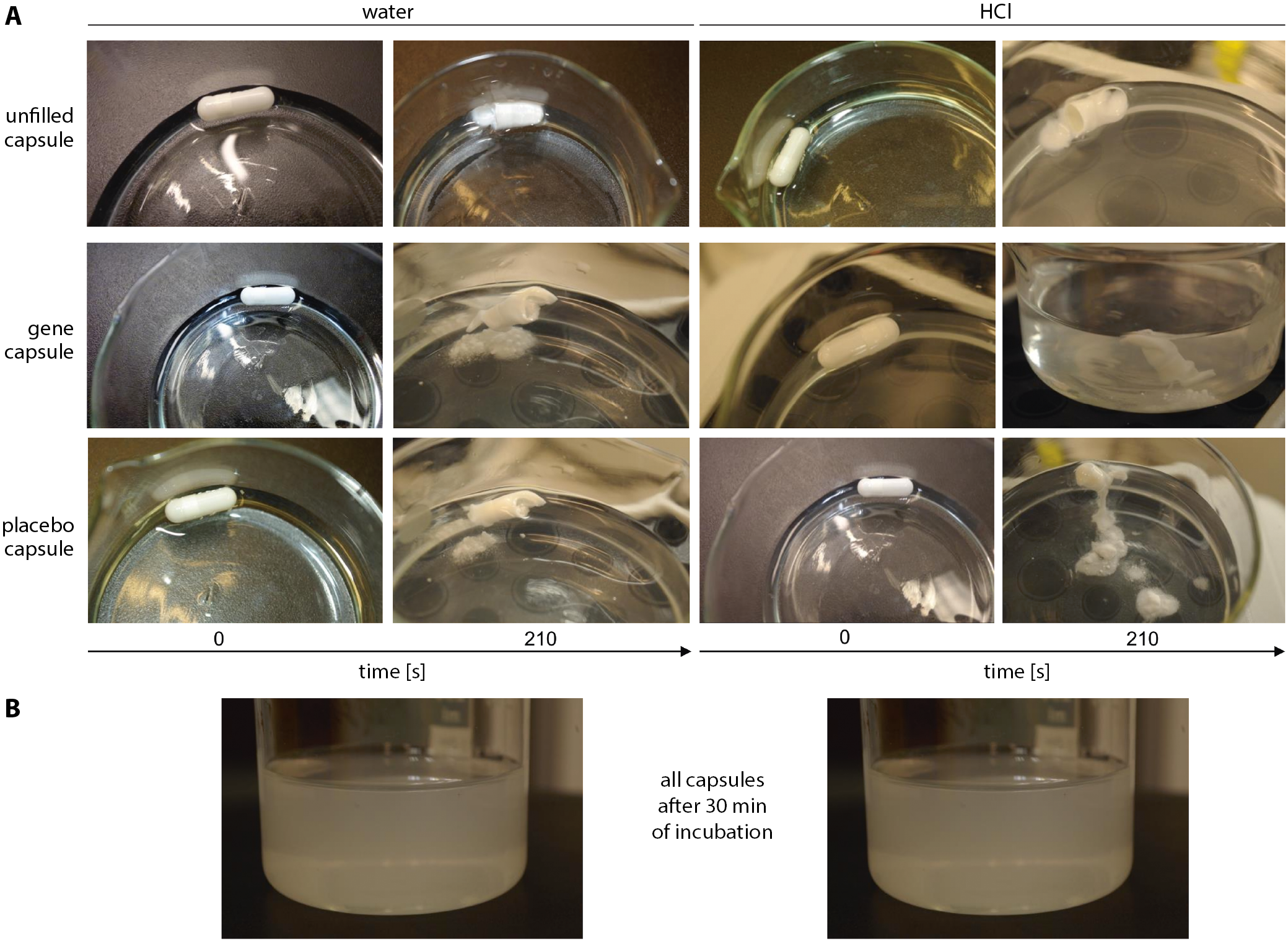

According to the indications of the Ph Pol XI,1 6 capsules were tested at one time. The temperature of the liquid was maintained at 37°C ±0.2°C (water or 0.1 M hydrochloric acid solution) and the test time did not exceed 30 min. The capsules were placed in 250 mL beakers containing 100 mL of water or hydrochloric acid solution (pH 1.5) in a shaking incubator (Jeio Tech, Daejeon, South Korea) at 37°C and 100 rpm. The capsules were observed and the appearance of the capsules and the time needed for disintegration were assessed (Figure 2). Additionally, the disintegration time experiment was carried out at a temperature 2°C lower than that recommended by the Ph Pol XI. This variant of the study at 35°C allowed for more accurate tracking of capsule disintegration and the preparation of appropriate photographic documentation (Figure 2).

DNA release from gene capsules

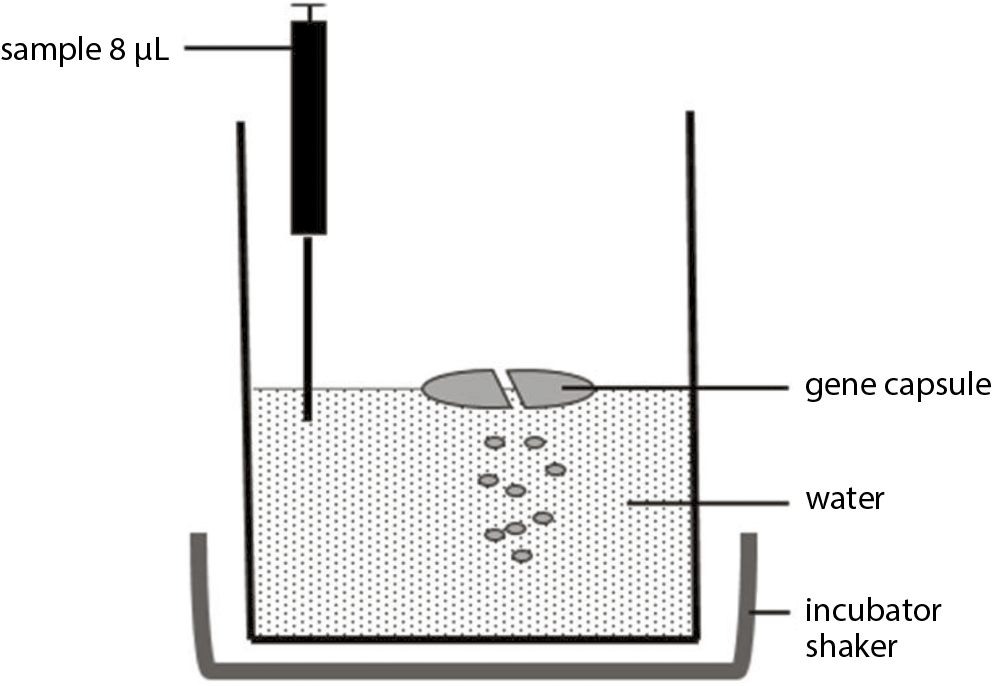

Test conditions similar to the nature and specificity of the active substance, i.e., plasmid DNA, were created. Water was used as the dissolution medium for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method of DNA detection. The level of HCl, phosphate buffer or NaOH recommended in the Ph Pol XI would disrupt the PCR process. Capsules were prepared as described in the “Formulation and preparation of gene capsules” section. Single capsules were placed in 250 mL beakers containing 100 mL water and placed in a shaking incubator (Jeio Tech) at 37°C and 100 rpm. Samples (8 µL) were collected every 30 s for 10 min and after 30 min (Figure 3).

PCR and electrophoresis

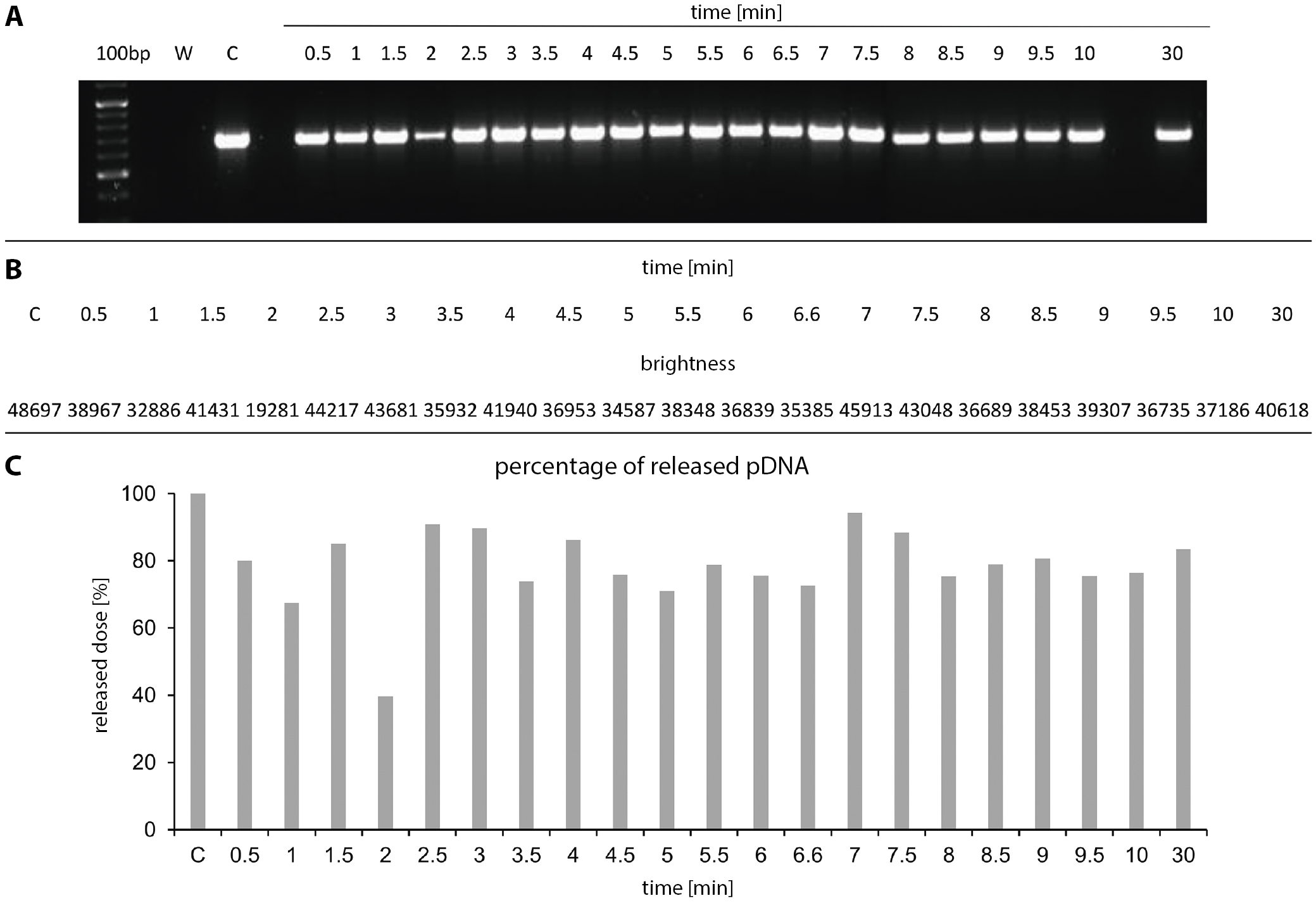

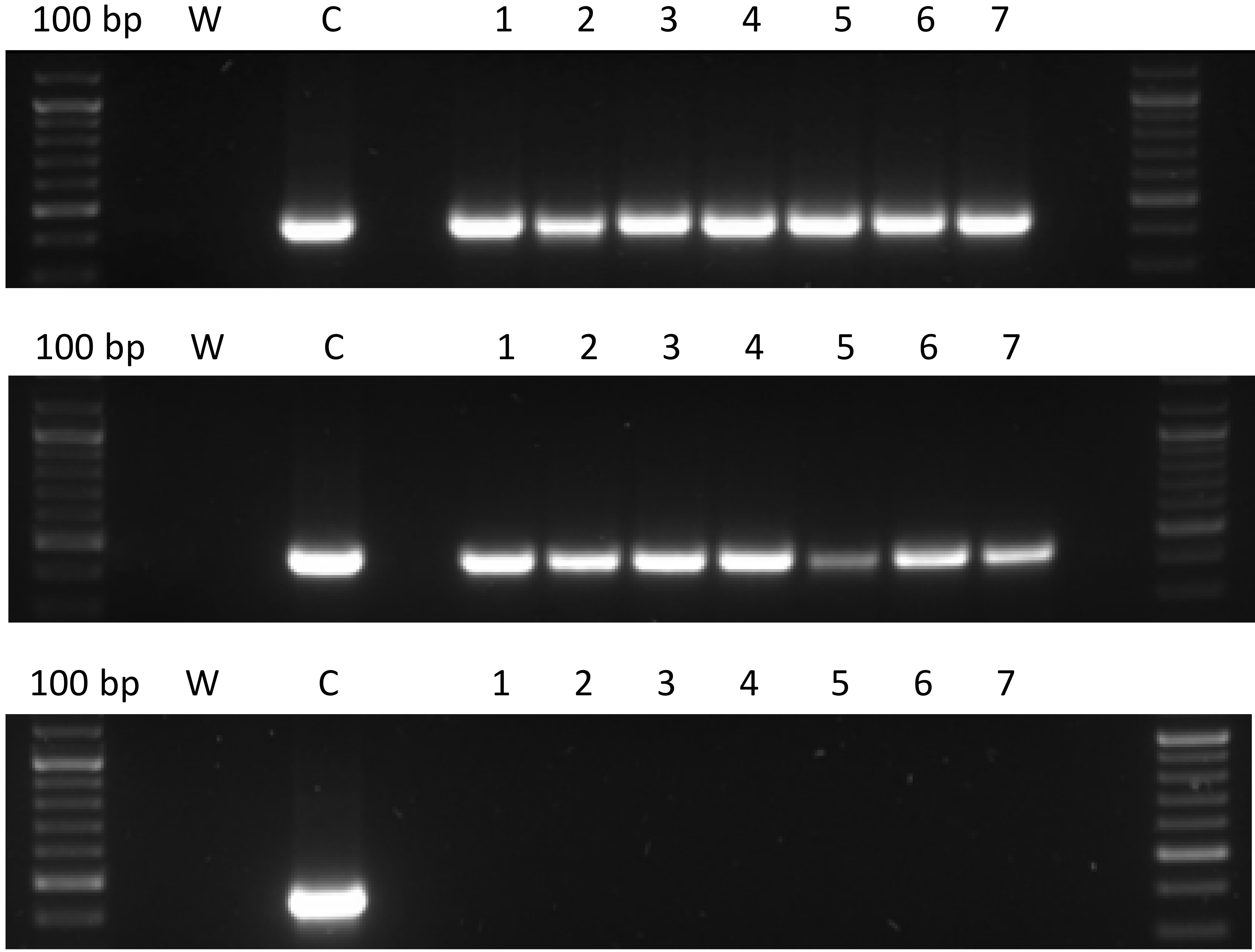

In the present study, the gene encoding ampicillin resistance cloned into the used plasmid was amplified. Primers with the following sequence were designed: 5’ATAGTTGCCTGACTCC3’ and 5’GTTACATCGAACTGGA3’. The reaction mixture (20 µL) contained 8 µL of collected sample, 10 µL of Master Mix 2× complete PCR buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), and 1 µL of each primer. The following PCR thermal profile was selected: 5 min at 94.0°C; 35 cycles (30 s at 94.0°C, 30 s at 42.1°C, 40 s at 72.0°C); and 10 min at 72.0°C. After the PCR, the samples were subjected to electrophoretic separation on 1.5% agarose gel enriched with SYBR Safe (Thermo Fisher), which is a cyanine dye that binds to DNA. Gene Ruler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher) was used as the size marker. The separated product was visualized and photographed under UV light using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) (Figure 4A). In order to assess how much of the active substance (DNA) was released from gene capsule within 30 min, the brightness intensity of the bands in agarose gel was analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, USA). The values used for the calculations of the released pDNA percentage are presented in Figure 4B.

Stability of gene capsules

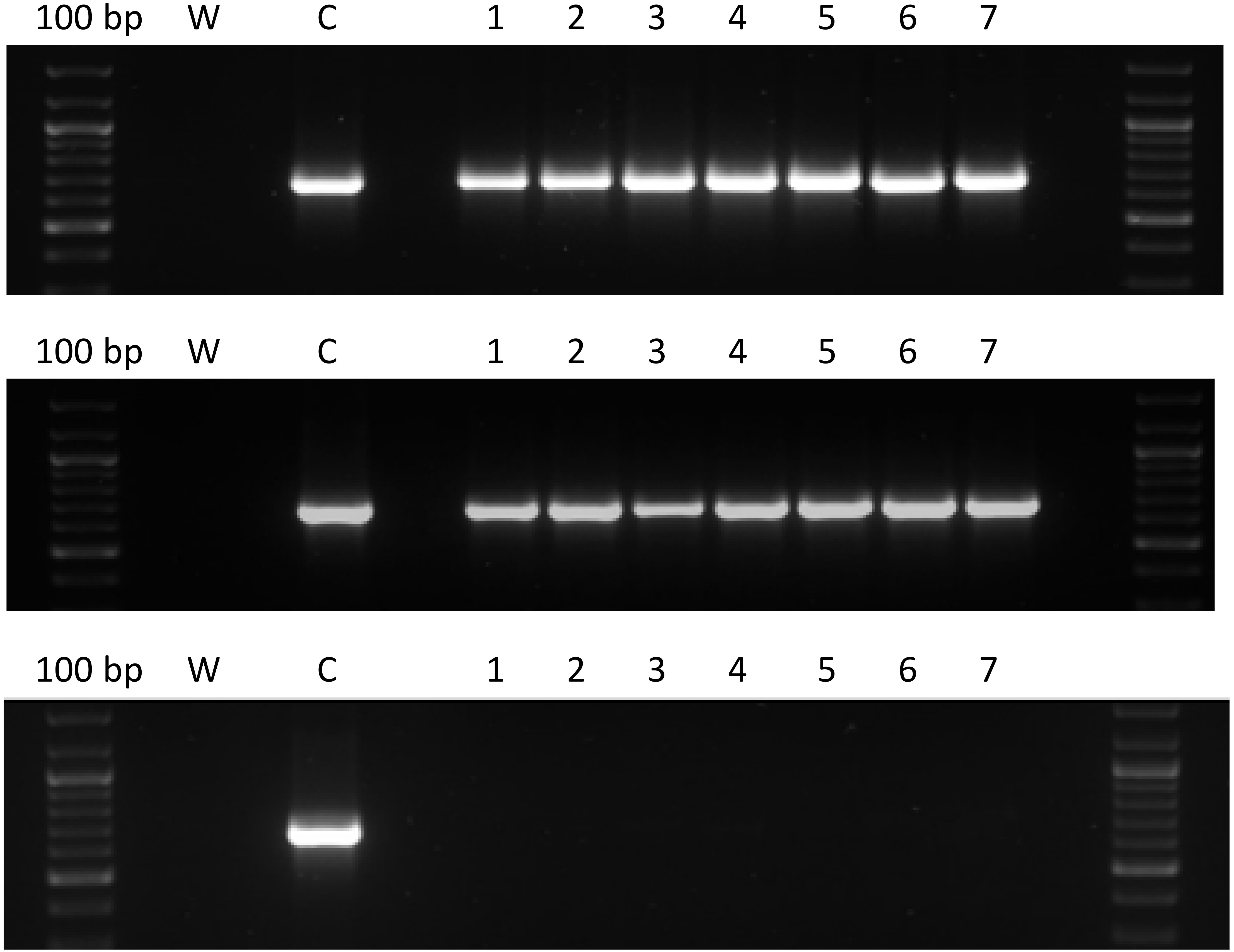

A method to test the stability of hard gelatin capsules containing lactose and pAAV/LacZ was designed. The obtained gene capsules and placebo capsules were stored at 4°C and room temperature (RT) for 1 day, 7 days, 14 days, 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months. After the indicated times, the capsules were dissolved in 250 mL beakers containing 100 mL of water and placed in a shaking incubator at 37°C and 100 rpm. The 8-μL samples were collected and PCR was performed using 2 types of designed primers. The 1st primer pair, as in the release test, allowed the amplification of the ampicillin resistance gene, while the 2nd pair of primers was complementary to the ITR LacZ coding fragment (primers annealing temperature of 54.9°C, sequences: 5’CATCTGCTGCACGCGAAGAA3’, 5’GAGGGAGTGGCCAACTCCAT3’). The PCR products were separated with electrophoresis. These methods were described in the above section titled “PCR and electrophoresis”.

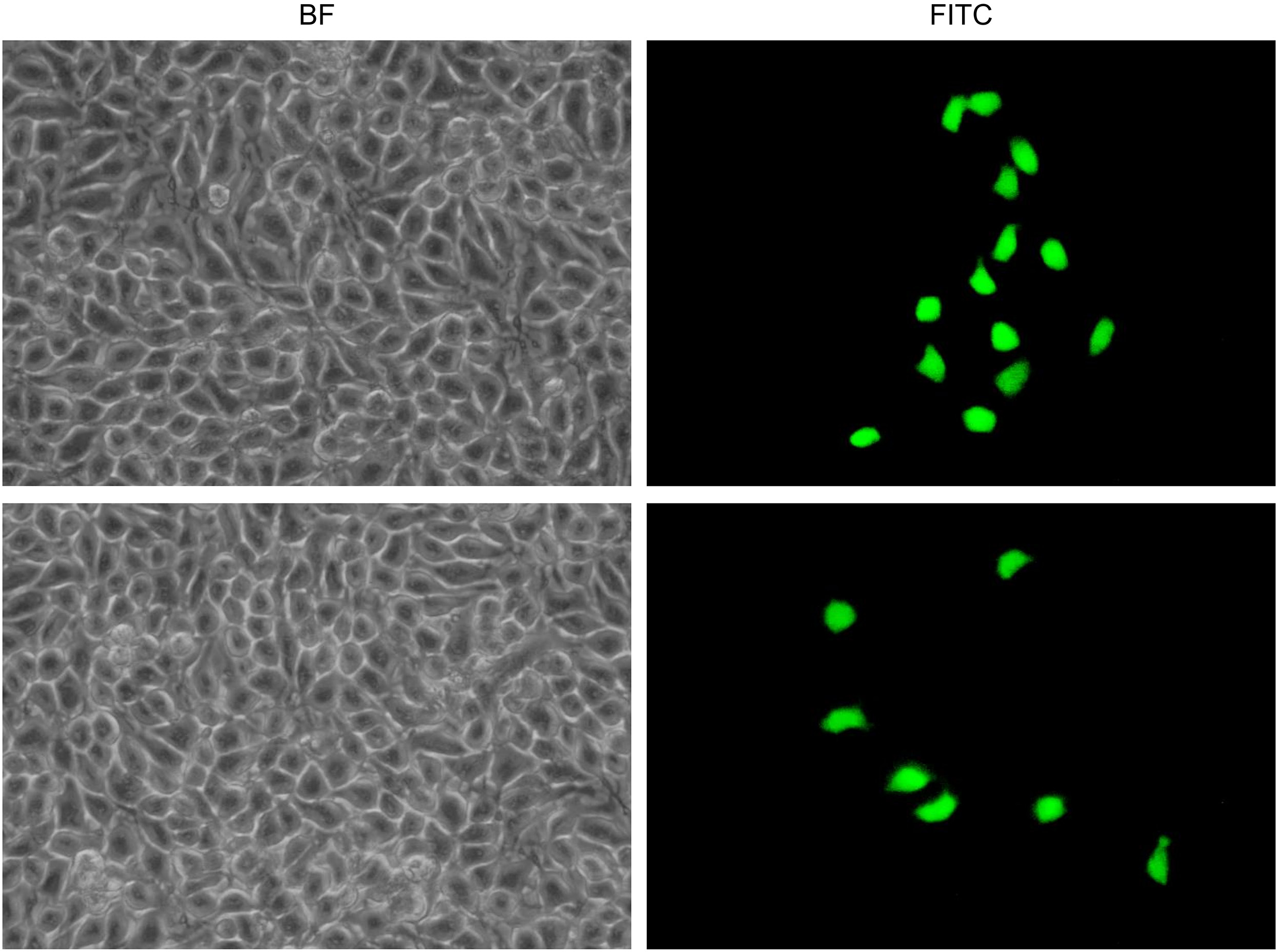

Assessment of biological (transduction) activity of gene capsules

The transduction activity of the obtained gene capsules was assessed under in vitro cell culture conditions. The gene capsules containing DNA (rAAV/GFP) were analyzed. The experiment used the mouse melanoma cell line B16-F10 (CRL-6475™; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, USA) maintained in a dedicated culture medium – Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) – supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). A mixture of antibiotics (antibiotic-antimycotic; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the medium in an amount ensuring 1% concentration. Melanoma cells were incubated at 37°C in air with an increased humidity and 5% CO2 concentration. The B16-F10 cells were seeded at 5 × 104 on 6 cm diameter culture dishes in dedicated medium and incubated for 24 h under standard culture conditions. Immediately prior to transduction, DNA and placebo capsules were prepared as described in the section “Formulation and preparation of gene capsules”. Each type of prepared capsule was introduced into 100 mL of DMEM enriched with 2% FBS and 2% mixed antibiotics, and then shaken at 37°C and 100 rpm for 30 min. Next, the culture medium from the cells seeded 24 h earlier was replaced with medium containing the released rAAV/GFP from the gene capsules. To each plate, 6 mL of this medium was added. After 48 h of incubation under standard culture conditions, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 2% mixed antibiotics. After another 48 h, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium with the same composition. On the 7th day after cell seeding, the expression of GFP in the test cells was examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX53; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a pE-300 white light system (CoolLED, Andover, UK). Photos were taken at ×10 magnification (in the bright field and with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter).

Results

Assessment of mass uniformity

of gene and placebo capsules

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether the prepared capsules met the requirements of the Ph Pol XI.1 Ten groups of 20 gene and placebo capsules were tested. In 7 out of the 10 groups of gene capsules and in 8 out of the 10 groups of placebo capsules, only 2 capsules exceeded the permissible deviation, but this occurred no more than 2 times. Table 1 and Table 2 present the findings for the representative gene and placebo capsules, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the weight of gene capsules 14 (11.2%) and 20 (−10.1%) slightly exceeded the allowable deviation. Table 2 shows that only the weight of placebo capsule 16 exceeded the deviation of ±10% (11.2%), while the weight of placebo capsule 15 was at the limit of the allowable deviation (−10.0%). Thus, the gene and placebo capsules prepared with a manual capsule filling machine met the requirements of the Ph Pol XI.1

Evaluation of capsule disintegration time

In this experiment, the disintegration time for gene, placebo and empty capsules was tested in water or hydrochloric acid solution (pH 1.5) at 37°C. Disintegration was observed, the time of degradation was measured and the percent of disintegration consistent with the definition in the Ph Pol XI was determined.1 As shown in Table 3, at 45 s the empty capsules were disintegrated in 80%. The gene and placebo capsules disintegrated slightly faster, and the disintegration at 45 s was estimated to be 90% (Table 3). The tested capsules met the test requirements according to the Ph Pol XI,1 as a minimum 16 out of 18 tested capsules were disintegrated. After 30 min, all tested capsules were completely dissolved (Figure 2).

The experiment was also carried out at 35°C in order to detect the disintegration point for the capsules. An effect of temperature on the disintegration rate of the capsules was observed: the difference of 2°C slowed disintegration of the capsules. The empty capsules disintegrated more slowly at the lower temperature compared to 37°C. At 210 s, they were disintegrated in 80%, while the capsules filled with lactose or lactose with plasmid at the same time were disintegrated in 90% (Table 4, Figure 2).

Assessment of pDNA release

from gene capsules

This study was performed with gene capsules containing 50 µg of plasmid each. The analyzed samples (8 µL) were collected every 30 s for 10 min and after 30 min (Figure 3). The PCR was performed. Then, the resulting products underwent electrophoretic separation in agarose gel. Plasmid release from the capsules was observed in the indicated time. After only 30 s in the sample, pAAV/LacZ was released. After 30 min, the band corresponding to the presence of pAAV/LacZ was also visible. Electrophoresis revealed that pDNA maintains the correct structure and was present in each sample. Moreover, the absence of a band in the sample marked as negative control (W) proved that the reaction was performed correctly (Figure 4A). Additionally, to assess the amount of DNA released from capsules within 30 min, the brightness intensity of the bands in the agarose gel was analyzed. The brightness values of the C band (positive control) and the other bands (showing release of pAAV/LacZ from the gene capsule within 30 min) were compared (Figure 4A). After 30 min, 83% of the DNA dose contained in the capsule was observed in the acceptor fluid (Figure 4C).

Stability of gene capsules

The aim of this experiment was to assess the stability and durability of the prepared capsules under the following conditions. The gene and placebo capsules were stored for 1 day, 7 days, 14 days, 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months at 4°C and room temperature (RT). After the stated times, the capsules were dissolved in water at 37°C. Seven capsules containing plasmid DNA (pAAV/LacZ) and 7 placebo capsules with only lactose were tested at each of the mentioned time intervals at both temperatures. Next, 8 µL samples were collected and PCR was performed using the 2 designed primers. Then, the samples then underwent electrophoretic separation on 1.5% agarose gel. The active substance (pAAV/LacZ) did not degrade at the 2 tested temperatures and after the indicated times, as confirmed by electrophoresis for each group. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show representative images after 1 day and 6 months, respectively, with use of the 2 types of primers.

Transduction activity of gene capsules

The transduction efficiency of B16-F10 cells was assessed with inverted fluorescence microscopy. Cell evaluation was performed on the 7th day of the experiment. The results are shown in Figure 7. As shown, the cells were successfully transduced with rAAV vectors released from capsules. The GFP-positive (GFP+) cells were grouped. From 4 to 14 GFP+ cells were observed in the microscope field of view. Effective transduction was documented in Figure 7, proving that the vectors carrying the reporter gene were not damaged during the overall procedure of transduction from gene capsules. During gene capsule preparation and release from the drug formulation, the rAAV vectors maintained their structure and managed to enter into the cells. The originally designed transduction procedure was successful. Moreover, the introduction of additional steps preceding transduction did not adversely affect the cell culture, as it was not infected with bacteria or fungi. These findings demonstrate the safety of the conditions used.

Discussion

Gene therapy is a promising method in medicine. Currently, gene therapy is mainly based on lentivirus or adeno-associated virus vectors, or the method of localization and repair of damaged CRISPR-Cas9 genes.24 New medicinal products delivering therapeutic genes, such as Glybera, Strimvelis, Kymriah, Yescarta, Luxturna, Zolgensma, and Zynteglo,16 have demonstrated the success of this treatment method and they encourage further intensive research. Considering the routes of administration of gene preparations, it seems that – apart from parenteral administration – oral, intranasal and transdermal forms may be particularly useful. Oral gene delivery is an extremely interesting therapeutic option due to the possibility of systematic and repeated administration of the drug, limited hospitalization and the features of the gastrointestinal tract. Since the intestines are easily accessible orally, rectally or endoscopically, it is not necessary to perform invasive surgery. The digestive tract has an unusually large surface area, which means there is a huge population of cells that can accept genes. There are also stem cells in the intestinal glands (e.g., Lieberkühn’s crypts) that are important for certain types of therapy. At the same time, it is worth emphasizing that the intestinal epithelium is highly vascularized, which may allow the efficient passage of newly synthesized proteins (resulting from gene transfer) into the bloodstream and, as a consequence, enable the treatment of systemic diseases.25 Studies have shown that therapeutic genes can be used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)20 and colorectal cancer,26 as well as systemic diseases such as hemophilia.27 However, the efficient delivery of genes via the gastrointestinal tract poses anatomical and physiological challenges for researchers, such as the presence of an acidic pH in the stomach, intestinal enzymes and bacterial flora.26 Oral systems should be designed to overcome the various conditions present in the digestive tract that may inactivate a sensitive substance like DNA. Therefore, it is important to design and carefully select materials for oral gene delivery. Recent achievements in oral gene therapy include strategies improving the efficiency of gene transfer, cell targeting and stability, as well as the adaptation of the drug form to the conditions present in the gastrointestinal tract.20, 28, 29, 30 One example of improving oral gene therapy is the functionalization of delivery carriers to enhance gastric stability and particle uptake or to target the active substance to the desirable cells. In a study by He et al., mannose-modified trimethyl chitosan-cysteine nanoparticles were used.28 This system allowed for targeted delivery of siRNA to intestinal macrophages and was effective in both, gastric and intestinal conditions. Promising targeted delivery methods include systems with bile acid conjugates that increase the stability of the active substance in the stomach and improve the uptake by intestinal enterocytes through bile acid transporters.20 In order to overcome the difficult conditions in the digestive tract, dual material particulate systems that combine various properties of materials to protect, release and deliver cargo to cells, can be prepared.29 Another interesting idea is smart delivery systems that can adapt to the local conditions in the digestive tract. An excellent example is enzyme and pH responsive nanogels. This system allows the nanogel to collapse and protects the payload under low pH conditions, yet expands under the higher pH conditions of the intestine to be degraded by intestinal enzymes to release cargo.30 Therefore, appropriate carriers are required to protect nucleic acids against the hostile environment of the gastrointestinal tract. Previous studies have used microspheres, chitosan, modified silica, and modified micelles.20, 21, 22, 23 Bhavsar and Amiji attempted to treat IBD by administering a plasmid encoding IL-10, which was incorporated in microspheres.20 Local expression of IL-10 reduced the levels of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., interferon α (IFN-α), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1, and IL-12). Moreover, the therapy resulted in an increase in body weight, restoration of colon length and mass, and inhibition of the inflammatory response. Guliyeva et al. developed chitosan microparticles containing plasmid DNA.21 The in vitro release of pDNA was pH-dependent: at the same time that the pH increased, the release rate decreased. In in vivo studies, after oral administration of pDNA-chitosan microparticles, the expression of the reporter gene was observed in histological sections of the stomach and small intestine. In another study, Li et al. conducted oral gene delivery tests using poly-L-lysine modified silica nanoparticles.22 This vehicle has low intestinal toxicity in BALB/C mice. The efficient expression of the reporter gene was detected in the stomach, and the expression in the intestine was mainly seen in mucosal cells. In the work of Guo et al., the ability of poly(allylamine)-based amphiphilic polymer micelles to deliver siRNA through the gastrointestinal tract was assessed.23 The physicochemical profiles showed that the transfection molecules self-assemble into complexes with nanometric diameters (150–300 nm) and a cationic surface charge (+20–30 mV). The transfection complexes were stable in the presence of saline solutions and simulated gastrointestinal fluids. The authors achieved up to 35% cellular uptake in in vitro studies, with successful release of siRNA from endosomes/lysosomes. The presented research examples emphasize the potential and functionality of different substances for oral gene delivery in gene therapy.

The rAAV/GFP contains rAAV-DJ as a vector, which delivers the GFP reporter gene. The well-characterized rAAV-DJ is a recombinant mosaic vector made from the DNA of 8 AAV serotypes that efficiently transduce cells from various cancer lines. Our previous studies revealed the high transduction activity of rAAV-DJ in the B16-F10 cell line.31, 32

Both viral and non-viral vectors were used in this study. Plasmids, adenoviral vectors and retroviral vectors are the most frequently used gene delivery vectors in clinical trials of gene therapy.33, 34 The AAVs are widely used in gene therapy as vectors due to their ability to ensure long-term gene expression and the lack of pathogenicity; thus, they are developed for gene delivery applications.31, 35 The AAV vectors are currently the most common type of viral vectors used in clinical trials of gene therapy.36

The aim of this study was to develop hard gelatin gene capsules based on lactose. Lactose monohydrate, popular in pharmacy recipes, was used. Lactose is a disaccharide composed of D-galactose and D-glucose linked by a β-1,4-glycosidic bond. It is nontoxic and does not have any pharmaceutical or pharmacodynamic interactions with other drug components.1, 12 Lactose is the most common diluent in tablets and capsules due to its good physical stability and water solubility, availability, and cost-effectiveness.37

A manual capsule filling machine was used to prepare the capsules (Figure 1), which facilitates and improves the preparation of divided powders in modern pharmacy recipes. It enables precise dosing of powder into hard gelatin capsules without weighing individual doses. The capsule machine ensures maximum purity of the drug and the esthetics of the final form. In this study, 100 placebo capsules were obtained and the mass uniformity test of single-dose preparations was performed based on the Ph Pol XI.1 The results met the requirements of the Ph Pol XI, i.e., a maximum 2 of 20 capsules slightly exceeded the permissible deviation, which for capsules weighing less than 300 mg can be ±10% (Table 1). We prepared 100 gene capsules that contained lactose and the active substance in the form of 10 µL of pAAV/LacZ solution in a concentration of 5 µg/µL per capsule (50 µg pDNA/capsule). Preparation of powder mass to fill the capsules containing pAAV/LacZ required care for the cleanliness of the workplace, as well as special care was required when combining the plasmid DNA with lactose. The tested gene capsules also met the requirements of the Ph Pol XI in terms of mass uniformity, i.e., a maximum 2 out of 20 gene capsules slightly exceeded the permissible deviation (Table 2).1

The capsules disintegrated, according to definition in the Ph Pol XI,1 in 45 s at 37°C and in 210 s at 35°C. The difference of 2°C slowed the disintegration of all capsules (empty, gene and placebo). According to the Ph Pol XI, the disintegration time should not be longer than 30 min. After this time, all tested capsules were completely dissolved. The short disintegration time of the capsules allows quick release and a rapid effect of the active substance.

In gene therapy research, it is important to determine the transduction efficiency of gene preparations, which is associated with the mechanism of DNA release from the drug. Therefore, the gene capsules were tested for active ingredient (DNA) release. Due to the experimental form of the tested drug as well as the type and specificity of the active substance used in the capsules (plasmid DNA), the original changes of the test conditions were introduced. This allowed the observation of pAAV/LacZ released from the capsules (as described in the Materials and Methods section). As shown in Figure 4, the presence of pDNA in the acceptor fluid was observed after 30 s, and DNA was detected in each of the collected samples. After 30 min, 83% of the dose contained in the capsule was observed.

To characterize the obtained gene capsules, stability experiments were also performed. The aim was to determine whether pAAV/LacZ in combination with lactose was stable under certain storage conditions and time. Assuming that the gene capsules are in the form of a prescription drug, pharmacists should determine their shelf life. Medicines that patients receive must have adequate quality and activity in the prescribed period. In accordance with the chapter “Medicines prepared in a pharmacy” in the National Monographs of Ph Pol XI, vol. 3,1 it is assumed that the maximum period of use of non-sterile solid preparations prepared with the use of prescription substances, when properly stored (temperature up to 25°C, protected from light, well-sealed containers), is not longer than 3 months.1 In our study, the active substance was not a prescribed substance. As the prepared form of the drug is experimental, it was tested for a much longer period of time. Interesting results were obtained in the stability assessment, which showed the extraordinary stability of pDNA. The released pDNA was stable for 6 months, both at a reduced temperature and RT. This is important information indicating that it is possible to prepare capsules for a patient for a longer period of dosing without fear of DNA inactivation.

In the context of the therapeutic potential of designed gene capsules, an important part of this study was the transduction of B16-F10 cancer cells using the viral vector from the gene capsules. The B16-F10 murine melanoma is one of the most commonly used cell lines in cancer research.38 The active ingredient in the capsules, which was used for B16-F10 cell transduction, was rAAV/GFP. The results are promising and indicate the possibility of introducing genes from viral vectors enclosed in a solid drug form. In vitro experiments (Figure 7) confirmed that the DNA released from the capsule was able to enter the cells, was expressed in the cells, and behaved as an active substance. The GFP + cells clearly confirmed the bioavailability of DNA from the capsule.

Limitations

The clinical utility of our results would be enhanced if in vivo animal studies would be conducted. Additionally, the proposed composition of the gene capsule does not include excipients commonly used in enteral formulations. In future research, it would be worth considering excipients that ensure an enteral form.

Conclusions

With reference to prior works about non-viral gene carriers taken orally,20, 21, 22, 23 this work has shown that viral vectors should be considered for the treatment of diseases, using orally administered gene therapy. Moreover, the performed experiments demonstrated that it is possible to obtain a solid form of a gene drug that combines gene therapy with a pharmacy recipe. The obtained gene capsules demonstrate the potential of gene therapy in increasing the availability of gene preparations for patients.