Abstract

Background. Isoastilbin (IAB) has been shown to have antioxidative and anti-apoptotic functions. A recent study found that IAB can reduce oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. However, whether the antioxidative function of IAB is also protective in other brain diseases remains unknown.

Objectives. To investigate the roles and underlying mechanisms of IAB in middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion (MCAO/R) in rats.

Materials and methods. Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham group, MCAO/R group, and 3 MCAO/R groups groups administered IAB (20 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg or 80 mg/kg) once a day for 3 days. Infarction size, modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS), oxidative stress markers, and neuronal apoptosis markers were used to assay the function of IAB.

Results. Compared with the MCAO/R group, administration of IAB reduced the infarction size and mNSS scores in MCAO/R rats. Isoastilbin also decreased the level of malondialdehyde (MDA) and enhanced the activity of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX). Isoastilbin treatment attenuated MCAO/R-induced neuronal apoptosis compared with the MCAO/R group, as indicated by the results of terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated X-dUTP nick end (TUNEL) and western blot assays. Isoastilbin also reversed MCAO/R-induced downregulation of SIRT1/3/6 protein expression.

Conclusions. These observations suggest that IAB protects against oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis in rats following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury through the upregulation of SIRT1/3/6, indicating that IAB might be a promising therapeutic agent for cerebral I/R injury.

Key words: apoptosis, oxidative stress, isoastilbin, focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury

Background

Ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke are among the leading causes of disability and death throughout the world.1, 2 Ischemic stroke is caused by obstructions in blood vessels, thereby putting target organs at risk of cell death.3 Although the most effective treatment for cerebral ischemia is to rapidly reinstate blood supply, thrombolytic therapy may increase the infarction size and aggravate ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury within the brain.1, 4 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new drugs for the treatment of cerebral I/R injury.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury in the brain involves complex pathophysiology, including the occurrence of oxidative stress, apoptosis and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion, all of which can lead to neuronal injury.5 Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced during ischemia, leading to neuronal apoptosis and neurological dysfunction.6 Specifically, NADPH oxidases generate ROS during I/R injury, which causes oxidative stress. This stress is marked by increased lipid peroxidation, decreased catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, and a decreased glutathione (GSH) level.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 High levels of ROS and oxidative stress will, in turn, trigger cell death through the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway following cerebral I/R injury.12 Mitochondrial permeability transition pores may open as a consequence of superfluous accumulation of ROS, resulting in lower mitochondrial transmembrane potential and increased production of caspase activators such as cytochrome c, ultimately initiating the caspase cascade and resulting in cell death.12 Geng et al. proposed that the apoptosis of neuronal cells is at least partially mediated by the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway in cerebral I/R injury.13 Consequently, the inhibition or reversal of oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis are a promising new method to attenuate cerebral I/R injury.

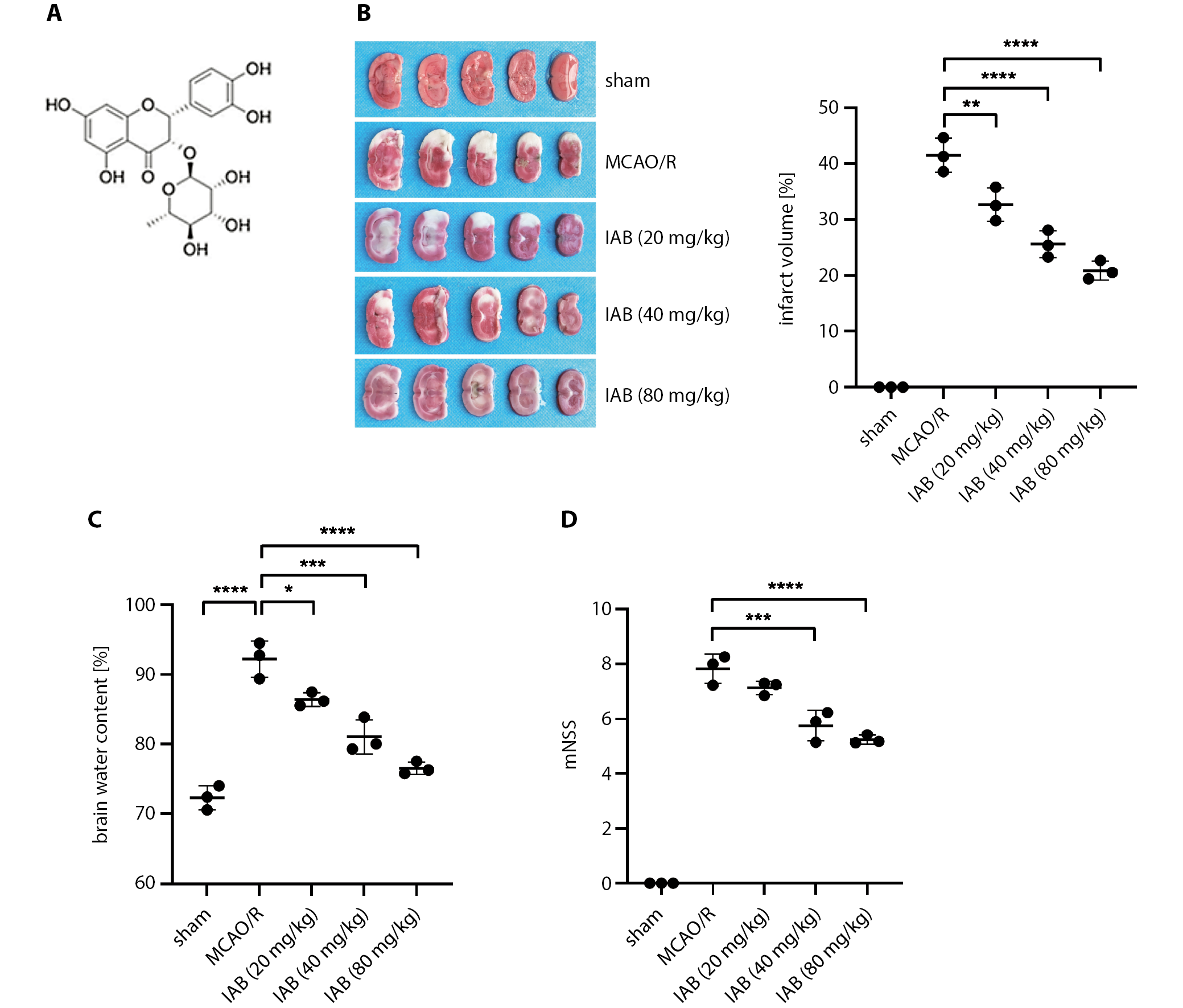

Isoastilbin (IAB) is a dihydroflavonol glycoside compound (Figure 1A) that is widely distributed in Sparassis crispa and Armillaria mellea.14, 15 As an anti-oxidative molecule, the extraction and purification of IAB from herbal preparations is well established.14, 16 However, if and how IAB may reduce oxidative stress in clinical diseases, remains unknown. Recently, Yu et al. investigated the protective effects of IAB on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in vivo, and found that IAB reduces oxidative stress through regulating the level of ROS induced by apoptosis.15 This protective effect of IAB in the nervous system suggests that it may serve as a treatment for I/R injury. Therefore, we established an in vivo model of middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion (MCAO/R) to examine whether IAB exerts protective effects against apoptosis and oxidative stress in the nervous system. Here, we demonstrate that IAB decreases cerebral I/R injury in rats by inhibiting apoptosis and reducing oxidative stress.

To explore the mechanism through which IAB attenuates I/R-induced damages, we focused on the SIRT signaling cascade. Recent studies have shown a protective role of SIRT1/3/6 in various diseases, including neural degeneration in the brain, blood vessel inflammation and fat body accumulation. Indeed, we found that IAB treatment increases the SIRT expression level during I/R injury, indicating that IAB may protect against cell apoptosis by upregulating SIRT expression. Taken together, our results suggest that IAB is a potentially useful treatment for clinical cerebral I/R injury.

Objectives

Our overall aim was to examine the effects and underlying mechanisms of IAB in I/R injury using MCAO/R animal model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats were acquired from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Company (Shanghai, China). Rats aged 60–90 days with normal body weight (200–250 g) were fed ad libitum food and water and maintained under a consistent environment (25 ±2°C, 40 ±10% relative humidity, and 12 h light/dark cycle). Animals were handled as per the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Jiamusi College, Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiamusi College, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine approved animal procedures (approval No. 20190815).

Establishment of MCAO/R injury

and IAB treatment

The toxicity of IAB was determined as previously described.15 Isoastilbin (Chengdu Purechem-Standard Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) was diluted to final concentrations of 20 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS). Animals were randomized into 5 groups: 1. sham; 2. MCAO/R; 3. MCAO/R followed by 20 mg/kg IAB; 4. MCAO/R followed by 40 mg/kg IAB; and 5. MCAO/R followed by 80 mg/kg IAB.

Rats were anesthetized using intraperitoneal (ip.) injection of 50 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Beijing, China). To introduce MCAO/R, we exposed the carotid arteries, namely the external carotid artery (ECA), right common carotid artery (CCA) and internal carotid artery (ICA). The ECA and CCA were proximally ligated. The ICA was ligated using a 0.285 mm monofilament suture, inserted into the lumen of the ICA for about 18 mm through the ECA stump to obstruct the middle cerebral artery (MCA). A Laser Doppler (USCN KIT INC., Wuhan, China) was used to confirm that blood flow was reduced to less than 20% of normal level. The sham group underwent the same operation; however, the arteries were not ligated. After 2 h of occlusion, the ligated arteries were reperfused and the rats were then gavaged with IAB (20 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg or 80 mg/kg) or PBS daily for 3 consecutive days. Lastly, 72 h after MCAO/R, the neurological capacity of the rats was assessed.

Evaluating rat brain infarct volume

Seventy-two hours after MCAO surgery, rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The brains were quickly isolated and cut into 2-mm slices. The brain slices were incubated with 2% 2,-3,-5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) solution for 30 min at 37°C and then fixed in 10% formalin overnight. Uninjured tissues were stained with red, while infarcted tissues were stained with white. A digital camera was used to acquire images of the slices and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, USA) was used to quantify the infarct volume. The infarct volume is reported as the percentage of total brain volume.

Water concentration in the brain

After IAB treatment, brains were quickly weighed to measure their wet weight. Subsequently, brains were dehydrated at 100°C for 24 h to assess their dry weight. The concentration of water in the brain was calculated as: ((wet weight ‒ dry weight)/wet weight) × 100%.

Modified neurological

severity score (mNSS)

Sensory, motor, balance and reflex neurological functions were assessed 72 h after MCAO surgery using mNSS.17 The severity of neurological deficits was ranked on a scale from 0 to 10, with a higher score indicating more severe damage to the nervous system.

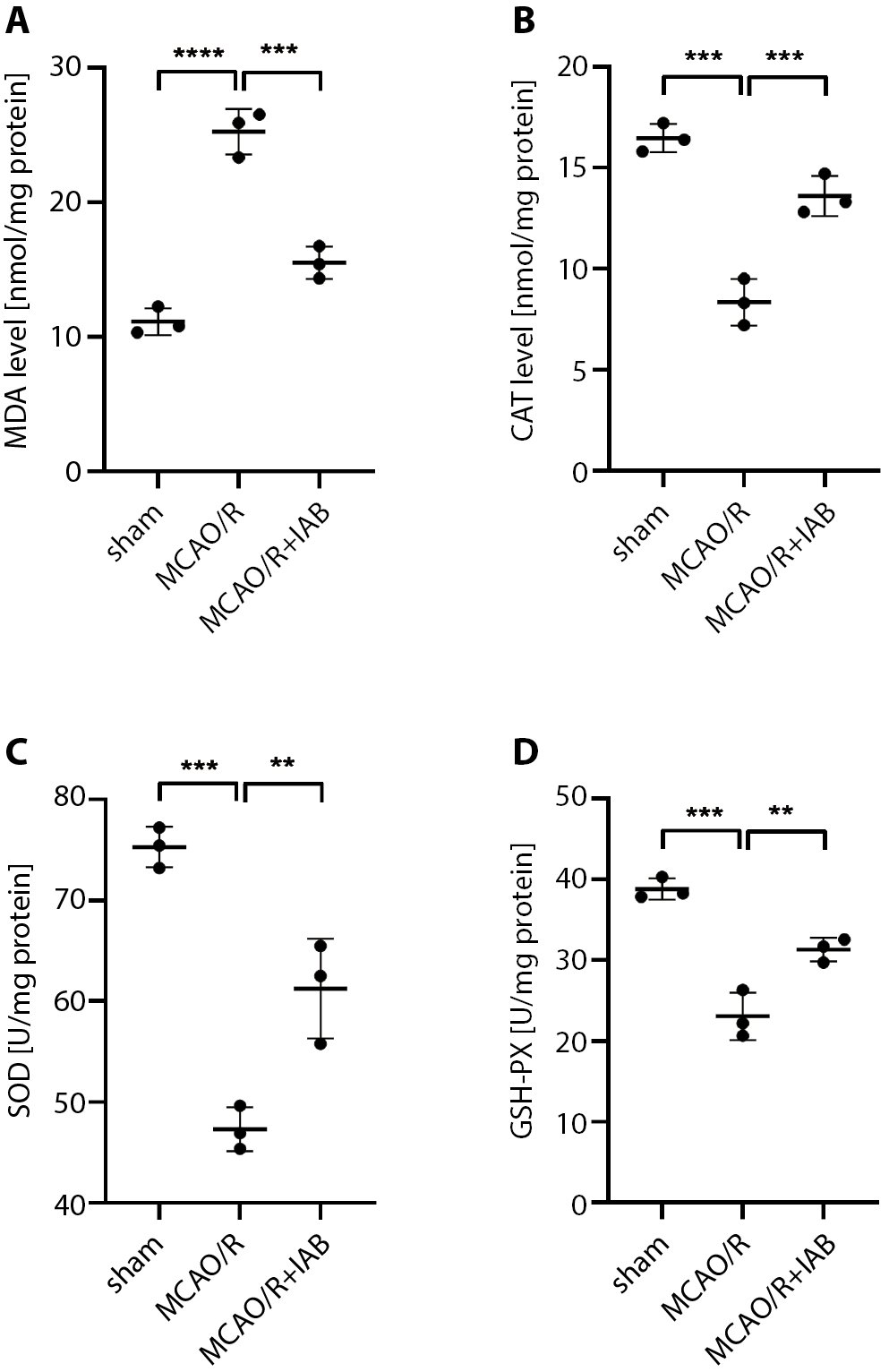

Measurement of superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX)

After IAB treatment, protein content was determined from brain tissues. Protein concentration of cortical homogenates was determined using BCA kits (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The SOD, MDA, CAT, and GSH-PX were detected using the corresponding kits (catalog No. A003-1, A001-3, A007, and A005; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Briefly, the supernatant of cortical homogenate was collected. For SOD, samples were incubated with WST-8/enzyme working solution at 37°C for 30 min. The absorption was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm. One SOD enzymatic activity unit (U) was defined as the amount of sample needed to achieve a 50% inhibition rate of WST-8 formazan dye. For MDA, samples were mixed with working solution and then heated at 100°C for 15 min. The absorption of supernatant was measured at a wavelength of 532 nm. For CAT, samples were mixed with CAT detection buffer and hydrogen peroxide solution and then incubated at 25°C for 5 min. The absorption was detected at a wavelength of 520 nm. For GSH-PX, samples were mixed with GSH at 37°C for 5 min. The absorption of supernatant was measured at a wavelength of 412 nm. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of GSH-PX in 1 mg of protein that catalyzed the consumption of 1 μmol/L GSH, while deducting the effect of the non-enzyme reaction.

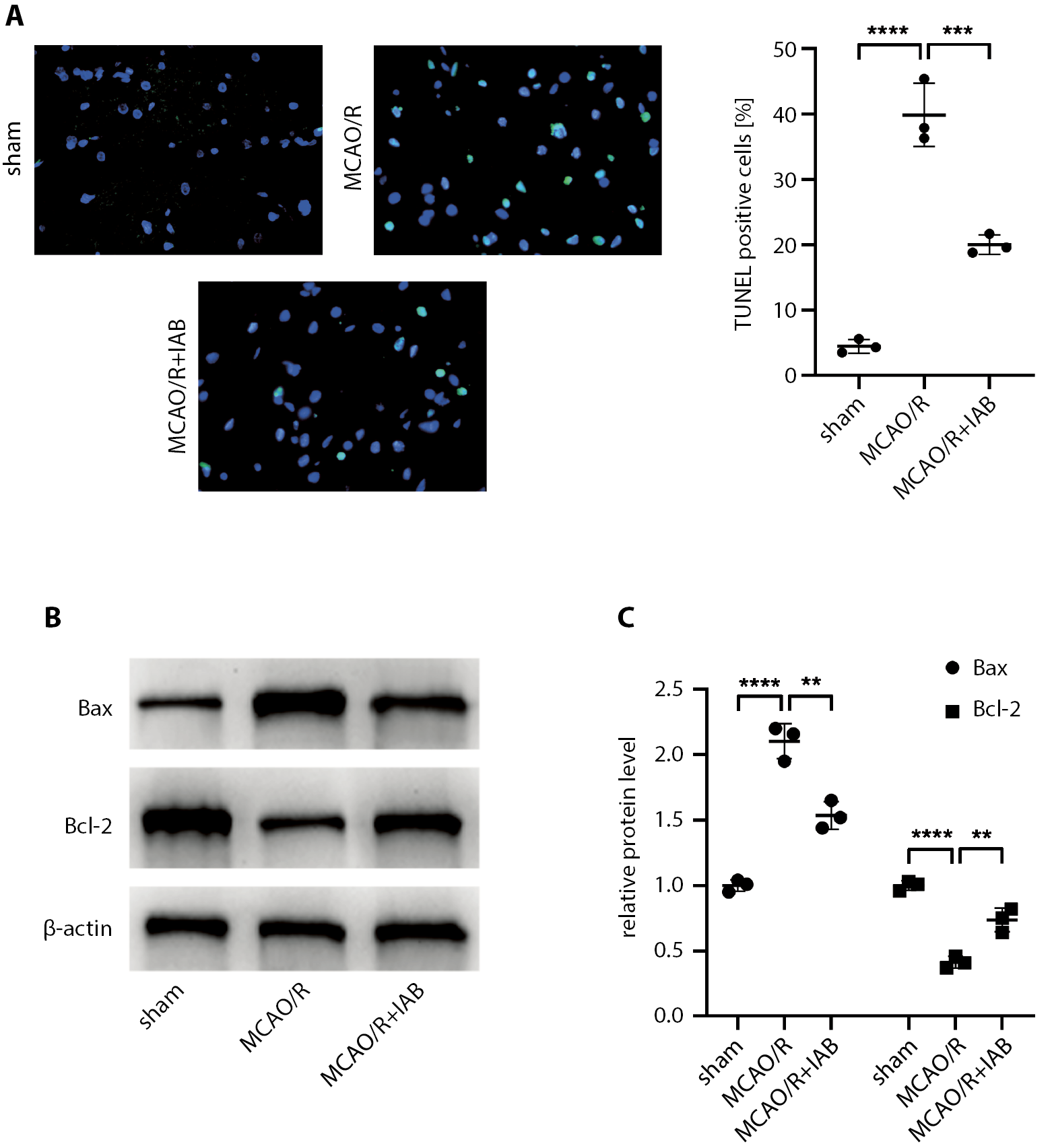

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining

Ipsilateral hemisphere brain tissues were isolated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Tissues were then cut into 5-μm slices and antigen exposed after 10 min of microwave heating in citrate buffer. Neuronal apoptosis was assessed using the TUNEL assay (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit; Roche, Penzberg, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, brain slices were placed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then, were incubated in the dark with the TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the nuclei were stained with 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were imaged and the apoptosis index was calculated as the number of TUNEL-positive cells divided by the total number of cells.

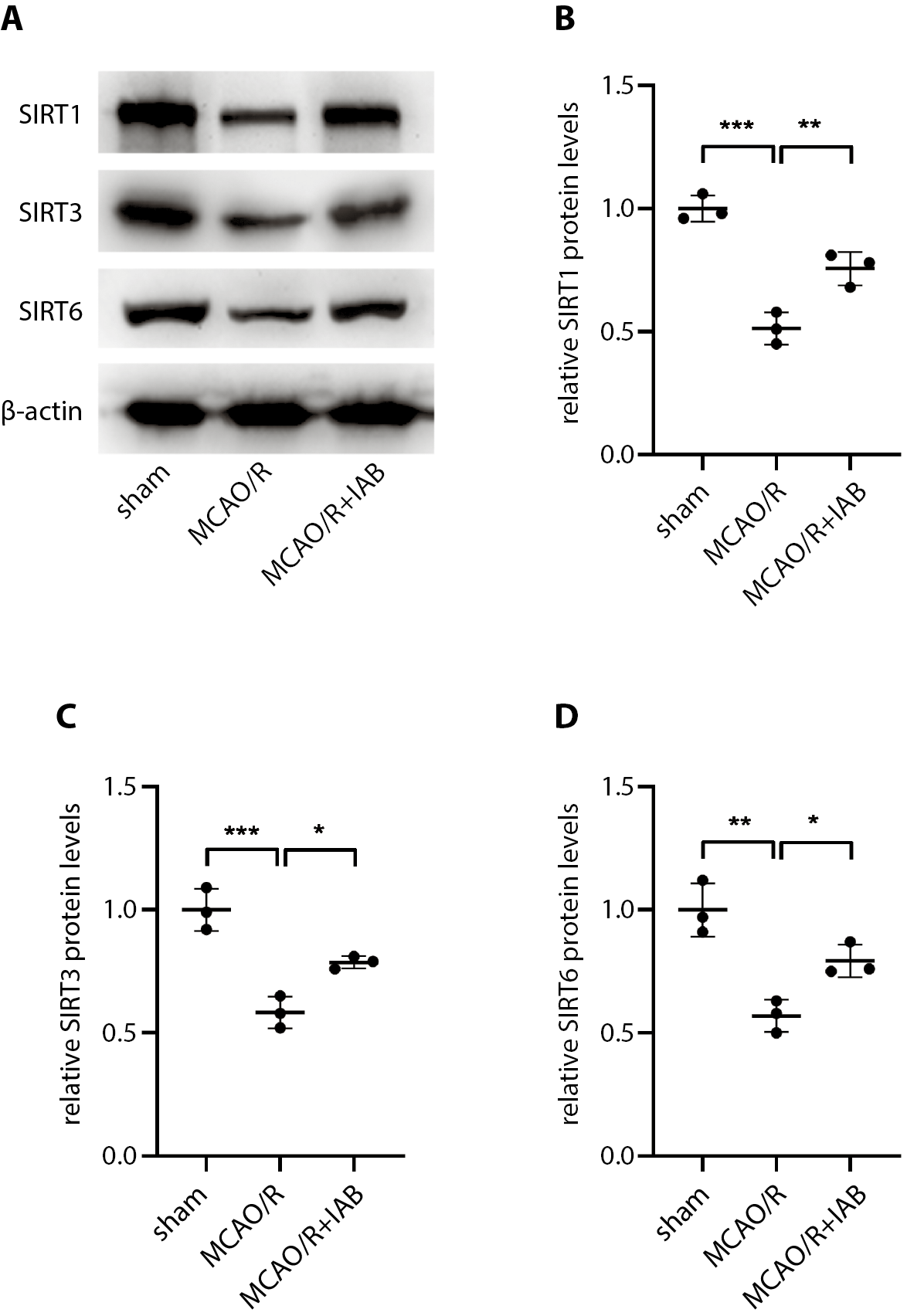

Western blot

Rat brain tissues were lysed using radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, Dalian, China). Proteins were subjected to 12–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, USA). Membranes were blocked using 5% fat-free milk and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were subsequently incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Specific signals of labeled proteins were detected using a chemiluminescence system. The β-actin was used to normalize the protein expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax and Sirtuin (SIRT1/3/6). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 3 independent experiments. Data from each group were confirmed to follow a normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using Prism v. 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). A value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. A post hoc power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Results

Isoastilbin protects neurons

from MCAO/R-induced injury

To explore if IAB protected neurons subjected to cerebral I/R, the concentration of water in the brain and infarct volume were analyzed. In control animals, there was no infarction and the water concentration was relatively low (Figure 1B,C; sham group). After MCAO/R surgery, we observed significant increases in the infarct size and water concentration (Figure 1B,C). Infarction and ischemic edema indicate that our approach successfully generated I/R model in rats. Interestingly, when we applied different concentrations of IAB (20 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg) immediately after injury, we observed dose-dependent recovery of infarction and ischemic cerebral edema (Figure 1B,C). This result suggests that IAB protects against ischemia-induced brain damage. Next, we examined cell apoptosis using the mNSS assay. As shown in Figure 1D, sham-operated rats exhibited no obvious neurological deficits, whereas MCAO/R rats showed significantly increased mNSS scores. Consistent with the morphological changes shown in Figure 1B and Figure 1C, IAB treatment significantly decreased the mNSS score of MCAO/R rats (Figure 1D). Taken together, these results provide evidence that IAB has a neuroprotective function in an in vivo rodent model of cerebral I/R injury. Given that a higher IAB concentration had better protective effects without obvious side effects, we used 80 mg/kg for the following experiments.

Isoastilbin attenuates oxidative stress in MCAO/R rats

To assess the influence of IAB on oxidative stress, the GHS-PX, MDA, SOD, and CAT levels were assessed after IAB treatment. Due to the increase in oxidative stress, rats subjected to MCAO/R had higher levels of MDA compared with sham rats. This effect was attenuated by IAB treatment (Figure 2A). Furthermore, CAT, SOD and GHS-PX levels decreased in MCAO/R rats compared to sham rats (Figure 2B,D). Treatment with IAB elevated the levels of CAT, SOD and GHS-PX in MCAO/R rats (Figure 2B,D), suggesting that IAB protected against cerebral I/R injury by attenuating oxidative stress.

Isoastilbin inhibits neuronal apoptosis in MCAO/R rats

Next, we utilized the TUNEL assay to assess neuronal apoptosis after cerebral I/R injury. As depicted in Figure 3A, there was an increased number of TUNEL-positive cells in MCAO/R rats, which was reduced by IAB treatment (Figure 3A). To explore the underlying mechanisms of IAB protection, we examined the expression of the apoptosis proteins Bax and Bcl-2 using western blot. In rats subjected to MCAO/R, the expression of Bax (pro-apoptotic marker) was upregulated, while that of Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic marker) was downregulated, compared with the sham group (Figure 3B,C). However, IAB treatment prevented MCAO/R-induced changes (Figure 3B,C). These results suggest that IAB inhibited neuronal apoptosis in MCAO/R rats.

Isoastilbin upregulates SIRT expression

Next, we sought to examine how IAB protects neurons from oxidative stress. The SIRT, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase mainly localized in mitochondria, has been found to be associated with cell survival and apoptosis, cell metabolism, and response to stress. The SIRT may activate mitochondrial signals and pathways to promote mitochondria proliferation and ATP generation. It also participates in inflammation, in a way that the reduction in SIRT leads to the increases in chronic inflammation factors, like NFκB and RelA/p65 activity.18, 19, 20 Interestingly, several studies have found that SIRT exerts a neural protective effect and attenuates oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of cerebral I/R injury.21 Here, we investigated brain expression of SIRT1/3/6 in rats subjected to MCAO/R. We found that MCAO/R injury decreased the protein levels of SIRT1/3/6, while IAB treatment attenuated these effects (Figure 4A–D). These data suggest that IAB might be protective in MCAO/R rats by upregulating SIRT1/3/6 expression in protection against oxidative stress.

Discussion

Previous research has established that I/R induces apoptosis and oxidative stress, resulting in neurologic disorders or even death.22, 23, 24 Oxidative stress is an important cause of brain reperfusion injury because during reperfusion, ROS concentration rises to a peak, which may potentially induce apoptosis or cell necrosis.25, 26, 27, 28 There are several well-established markers of oxidative stress. For example, MDA, a cytotoxic compound produced by lipid peroxidation,29 is increased in rat cardiomyocytes after I/R damage.30 The antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT and GHS-PX play important roles in scavenging superoxides and preventing oxidative damage.31, 32 Moreover, changes in the activity of these enzymes are also related to oxidative stress. Attenuating oxidative stress is a potential way of protecting tissues from I/R injury.

A recent study demonstrated that the neuroprotective effect of IAB might be due to the modulation of oxidative stress. Specifically, the study found that IAB inhibited ROS generation and induced SOD and GSH-PX to ameliorate oxidative damage in a mouse AD model.15 However, if and how IAB protects against I/R injury in brain, is not yet known. In the present study, we demonstrated that IAB successfully attenuates cerebral I/R injury by reducing the infarct volume and neurological deficits after MCAO/R injury. To test whether the effects of IAB are due to attenuation of ROS species, we measured several markers of oxidative stress. Isoastilbin treatment after MCAO/R was found to decrease MDA levels, but increase CAT, SOD, and GSH-PX activity. These results suggest that the underlying mechanism of IAB-mediated neuroprotection against I/R injury is through the reduction of oxidative stress.

Indeed, cerebral I/R is able to induce apoptosis of neurons.33, 34 The activation of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bax and Bak) and parallel inactivation of anti-apoptotic proteins (such as Bcl-2) occurred during cerebral I/R injury. Both, Bcl-2 and Bax are found in the exterior part of the mitochondrial membrane, and participate in the modulation of cell apoptosis.35, 36, 37 Previous studies have shown that Bcl-2 overexpression blocks neuronal death in vitro and in vivo.38 Erfani et al. found that the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was increased during cerebral I/R injury, contributing to neuronal apoptosis.39 Moreover, Bax upregulation and Bcl-2 downregulation were found in mice brains subjected to MCAO/R.40 In addition, IAB has been found to modulate the protein expression levels of both Bcl-2 and Bax to improve the redox system in mice with AD, indicating the anti-apoptotic role of IAB in this condition.15 In the present study, we showed that the administration of IAB reduced I/R-induced neuronal apoptosis in vivo by downregulating Bax and upregulating Bcl-2. These findings imply that the neuroprotective capability of IAB is dependent on its anti-apoptotic activity in rats. However, I/R may also lead to necrosis, which is not mediated by oxidative stress.25, 26, 27, 28 It is of great interest to examine whether IAB may also function by inhibiting necrosis to attenuate I/R injury.

To examine the mechanism through which IAB attenuates oxidative stress, we focused on SIRT proteins. A previous report has found that overexpression of SIRT3 inhibited mitochondrial fission to protect against cerebral I/R injury.41 Moreover, SIRT6 can protect the brain against I/R damage through the suppression of oxidative stress.42 Herein, we discovered that SIRT1/3/6 was significantly downregulated in MCAO/R rats, whereas administration of IAB increased the expression of SIRT1/3/6. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that IAB may increase SIRT1/3/6 protein expression to attenuate oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis induced by cerebral I/R injury.

Limitations

There are many different protective pathways against oxidative stress. Here, we demonstrated that the signaling mechanism of IAB protection is through SIRT 1/3/6. However, other mechanisms against oxidative stress or cerebral I/R injury should be further elucidated. During I/R injury, both apoptosis and necrosis are involved; however, we only focused on apoptosis. Thus, further research on the role of IAB in necrosis will be necessary to fully explain the protective function of IAB during I/R injury.

Conclusions

Here, we demonstrated that IAB can alleviate oxidative stress and apoptosis of neurons in rats subjected to cerebral I/R. Moreover, the antioxidative stress and anti-apoptotic functions of IAB might arise through the regulation of the SIRT1/3/6 expression. Taken together, our data suggest that IAB is a candidate treatment for cerebral I/R injury.