Abstract

Background. The T lymphocyte subset levels are an indicator used to evaluate the immune status of the body. In recent years, many studies have investigated the correlation between T lymphocyte subset levels and postoperative infection.

Objectives. To investigate the incidence of infection after liver cancer interventional therapy and its influence on T lymphocyte subset levels and toll-like receptors (TLRs).

Materials and methods. A total of 325 patients with primary liver cancer receiving interventional therapy were divided into an infection group (n = 37) and a non-infection group (n = 288). The infection site and the distribution of pathogenic bacteria in the infection group were observed. The serum T lymphocyte subset level and TLR2 and TLR4 levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells were compared. The clinical value of the postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels in evaluating infection was analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results. Among 51 strains of pathogens isolated from the infected patients, strains of Escherichia coli (27.45%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19.61%) were the most commonly observed. After surgery, the levels of CD3+, CD4+ and CD4+/CD8+ decreased, while the level of CD8+ increased in both groups; the levels of TLR2 and TLR4 decreased in the non-infection group, while the levels of TLR2 and TLR4 increased in the infection group (all p < 0.05). Furthermore, the decreases and increases were more significant in the infection group than in the non-infection group (all p < 0.001). The area under the curve of postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels in evaluating infection were greater than 0.700 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions. Gram-negative bacteria account for the majority of infections in patients after liver cancer interventional therapy, and the main infection sites are the lung and abdomen. The infected patients show changes in T lymphocyte level and decreased immune function. The TLR2 and TLR4 can be used as auxiliary indicators to evaluate infection after surgery.

Key words: T lymphocytes, toll-like receptor, intervention, liver cancer, postoperative infection

Introduction

Liver cancer is a common malignant tumor characterized by high morbidity and mortality.1, 2, 3 For patients with early liver cancer, surgery is the most effective treatment. However, in most cases, the tumor has progressed to the middle or advanced stage at diagnosis, and patients have missed the best opportunity for surgery due to the insidious onset of symptoms.4, 5, 6 Transhepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, which is one of the important local treatments for liver cancer, has the advantages of minimal trauma and rapid postoperative recovery. For these reasons, it is widely used in the treatment of advanced liver cancer and shows significant effects.7 Nevertheless, interventional therapy itself is invasive and the immune function of patients is often impacted, potentially resulting in postoperative infection. The rate of postoperative infection is reported to be about 10–15% in patients with liver cancer.8, 9 Therefore, further research on infection after liver cancer interventional therapy and biomarkers for predicting infection is clinically valuable for timely and effective prevention and control measures. Inflammatory response and immune dysfunction are the main mechanisms of postoperative infection. Infection can lead to a persistent inflammatory state, which can result in further immune dysfunction.

The T lymphocyte subset levels are an indicator used to evaluate the immune status of the body. In recent years, there have been many studies investigating the correlation between T lymphocyte subset levels and postoperative infection; however, there have been few reports on infection after interventional therapy for liver cancer. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), as a class of pathogen recognition receptors, can activate adaptive immunity by promoting the expression of inflammatory factors and participate in the inflammatory response of anti-infection.10 A previous study confirmed that TLRs are closely linked to infection and that TLR levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are increased in infected patients.10 However, the role and mechanism of TLRs in postoperative infection of liver cancer remain unclear.

Objectives

We aimed to explore the incidence of infection after liver cancer interventional therapy and the effect of infection on T lymphocytes and TLR levels in order to provide a reference for the prevention and treatment of infection in liver cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Study design

This prospective study included 325 patients with primary liver cancer who received interventional therapy in our hospital from July 2015 to July 2018. General data were collected, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), pathological type, Child–Pugh classification, site and size of lesion, clinical stage, fasting blood glucose level, and smoking and alcohol history. Each patient was assigned to the infection group (n = 37) or non-infection group (n = 288), according to their condition. The diagnostic criteria for infection were based on the Diagnostic Criteria for Nosocomial Infection.11 This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for the study if they met the diagnostic and staging criteria of hepatocellular carcinoma12; had no infection and did not take anti-infection drugs within 3 months before the intervention; received no targeted drug therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other drug therapy; had no other malignant tumors; were aged ≥18 years; and provided written informed consent or consent was provided by their families.

Patients were ineligible for the study if they had complications with infectious diseases before interventional surgery or had infection within 6 h after surgery; were administered immune agents or glucocorticoids within 3 months before surgery; had other underlying diseases; were not suitable for surgery; or had incomplete clinical data.

Methods

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

All patients were treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE). The chemotherapy regimens were as follows: 0.75–1.25 g of 5-fluorouracil (H31020593; Xudonghaipu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China), 80–120 mg of cisplatin (H37021358; Qilu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Jinan, China), 200 mg of oxaliplatin (H20093167; Qilu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), and 80–120 mg of epirubicin (H20000496; Pfizer Pharmaceutical (Wuxi) Co. Ltd., Wuxi, China). A gelatin sponge (20193141731; ConvaTec Limited, Shanghai, China) was used as the embolic agent. The dosage of chemotherapeutic drugs and embolic agents depended on the tumor size and the extent of embolization.

Diagnosis of infection

and identification of pathogens

Biological samples from the sites of suspected infection (e.g., abdomen, lung, blood, intestine, surgical site, urinary system, skin) were collected, inoculated into culture media, and cultured at a constant temperature of 37°C for 2–3 days. Subsequently, the bacteria were isolated for strain identification (MicroScan WalkAway Plus 96; Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, USA).

Measurement of T lymphocyte subset levels

Fasting venous blood (3 mL) was drawn from each patient before treatment and within 6 h after treatment (before the occurrence of infection). The CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells in whole blood were counted with flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter Inc.), and the changes in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio before and after treatment were calculated. The cell counting kits were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Measurement of TLR2 and TLR4 levels in PBMCs

Fasting venous blood (3 mL) was drawn from each patient before treatment and within 6 h after treatment (before the infection). Each blood sample was divided into 2 parts: 1 was mixed with monoclonal antibodies FitC-CD14 and PE-TLR2, and the other with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. The samples were fully mixed and maintained at 4°C for 30 min. Next, 2 mL of red blood cell lysate was added to both parts of the sample, which were mixed and allowed to stand in the dark for 20 min at room temperature. Then, the samples were washed twice with PBS and centrifuged to remove the supernatant. The PBS was added to adjust the concentration. The positive detection rate of TLR2 mononuclear cells was determined with flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter Inc.). The positive detection rate of TLR4 was similar to that of TLR2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The χ2 test was adopted for the comparison of enumeration data expressed as a ratio or percentage. The data were checked for a normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data that followed a normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (x ± SD), while data that did not meet the normal distribution were expressed as a percentile. The independent sample t-test was used for the comparisons between the 2 groups, and the paired sample t-test was applied for the comparison before and after intervention within the same group. Moreover, ROC curves were used to analyze the clinical value of postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels in evaluating postoperative infection. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of general patient characteristics

Of the 325 patients, 37 developed postoperative infection (infection rate 11.38%). There was no significant difference in gender, age, BMI, pathological type, Child–Pugh classification, site and size of lesion, clinical stage, fasting blood glucose level, and smoking and alcohol history between the 2 groups, suggesting that the 2 groups were comparable (all p > 0.05, Table 1).

Site of infection and distribution of pathogenic bacteria

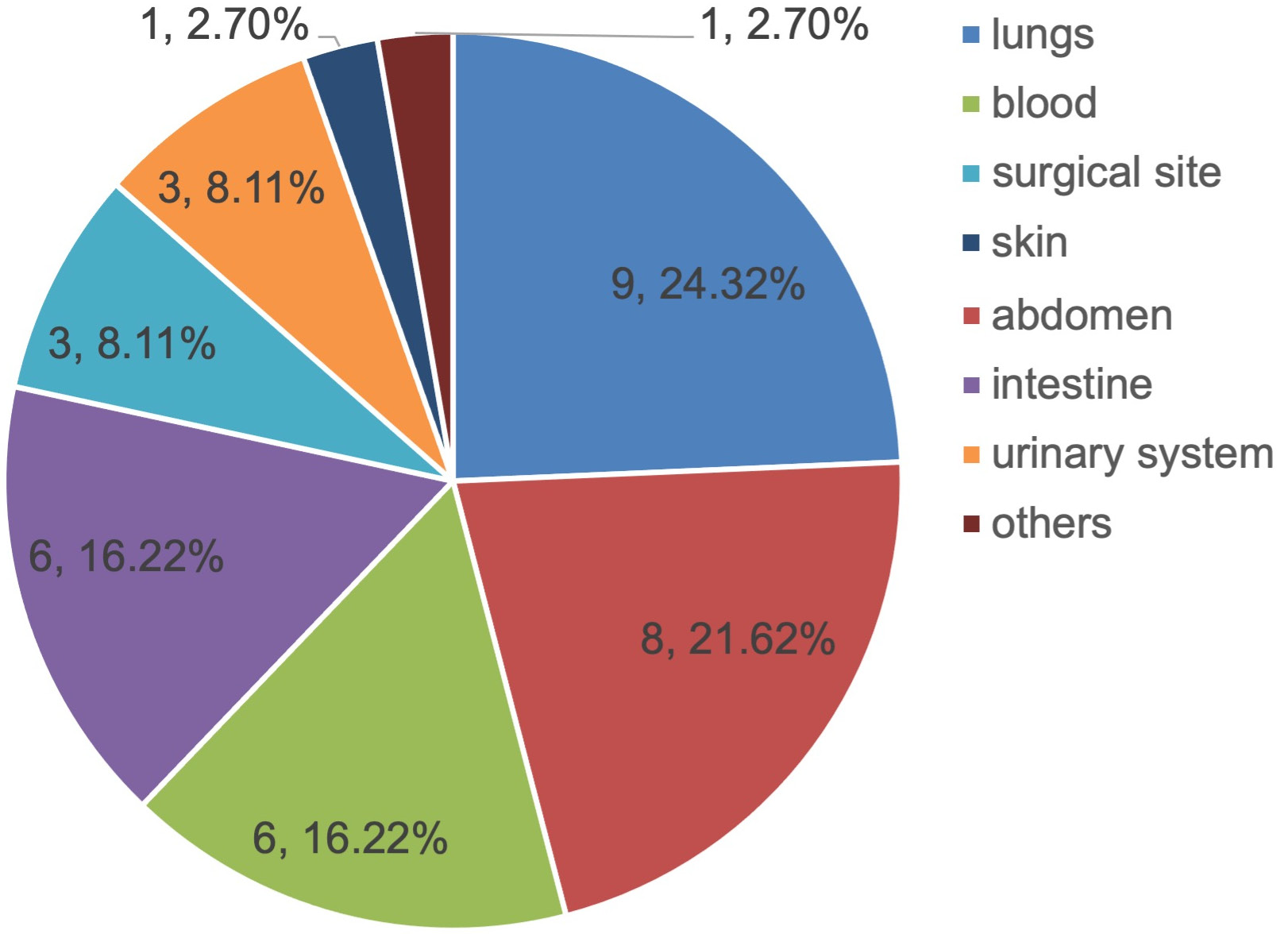

Among the 37 patients with infection, the main infection sites were the lung (24.32%), abdomen (21.62%), blood (16.22%), intestine (16.22%), surgical site (8.11%), urinary system (8.11%), skin (2.70%), and others (2.70%). A total of 51 strains of pathogenic bacteria were isolated from the infected patients. There were 38 strains of Gram-negative bacteria (74.51%), which were mainly Escherichia coli (27.45%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19.61%), and 13 strains of Gram-positive bacteria (25.49%), which were mainly Staphylococcus aureus (11.76%) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (7.84%). See Figure 1 and Table 2 for additional details.

Comparison of T lymphocyte subset levels before and after surgery

Before surgery, no significant differences were identified in CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+/CD8+ levels between the 2 groups (all p > 0.05). After surgery, the CD3+, CD4+ and CD4+/CD8+ levels were significantly decreased, while the CD8+ level was significantly increased in both groups (all p < 0.05). The CD3+, CD4+ and CD4+/CD8+ levels were lower, and the CD8+ level was higher in the infection group compared to the non-infection group (all p < 0.001) (Table 3.

Comparison of TLR2 and TLR4 levels in PBMCs before and after surgery

Before surgery, the TLR2 and TLR4 levels in PBMCs were 53.86 ±19.97% and 51.96 ±18.83% in the infection group, and 54.12 ±18.36% and 52.23 ±17.92% in the non-infection group, respectively. No significant differences were observed in the TLR2 and TLR4 levels in PBMCs between the 2 groups (both p > 0.05). After surgery, the TLR2 and TLR4 levels in the infection group were increased (61.63 ±14.43% and 63.98 ±22.28%, respectively; both p < 0.001), while the levels in the non-infection group were decreased (42.57 ±8.47% and 33.60 ±10.54%, respectively; both p < 0.001). The TLR2 and TLR4 levels in the infection group were significantly higher than those in the non-infection group (both p < 0.001, Table 4).

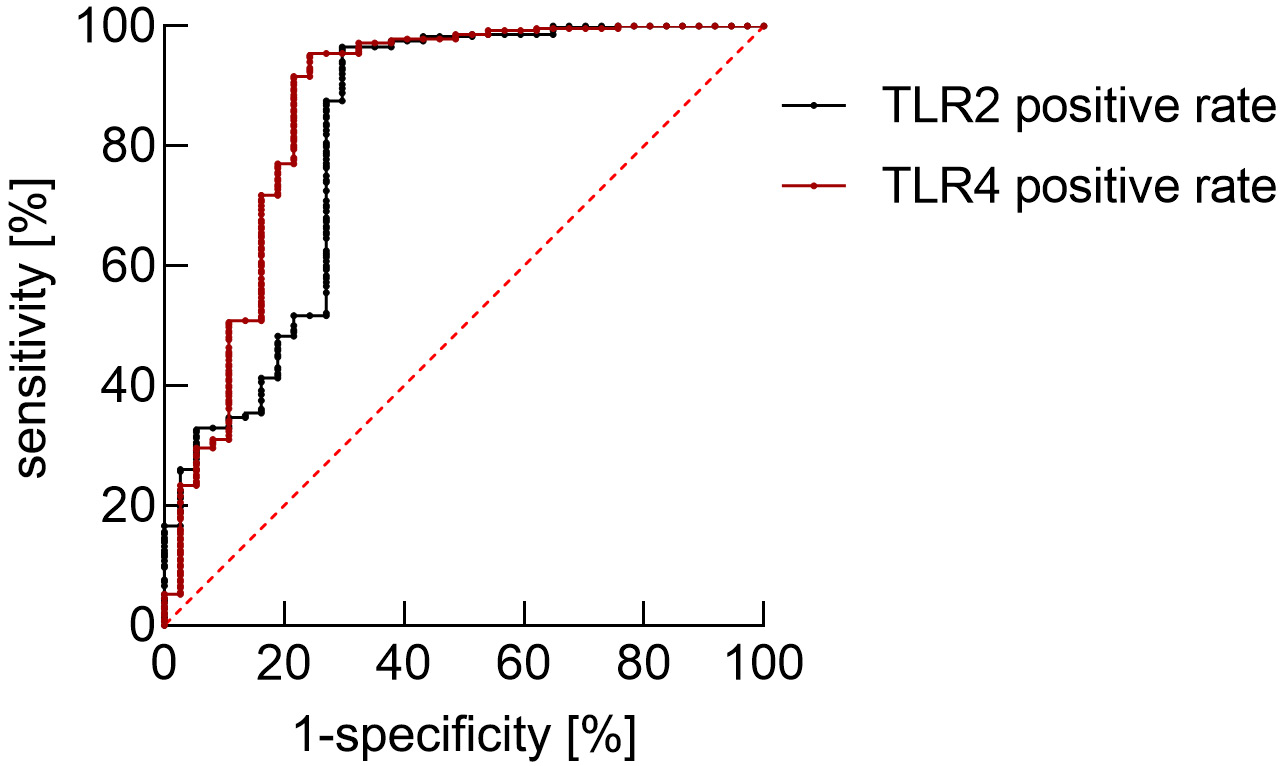

ROC curves for TLR2 and TLR4 levels

When the area under the curve (AUC) of the postoperative TLR2 level for evaluating postoperative infection was 0.816, the cutoff value was 60.666%, with the sensitivity of 0.703 and the specificity of 0.965. When the AUC of the postoperative TLR4 level for evaluating postoperative infection was 0.865, the cutoff value was 53.679%, with the sensitivity of 0.757 and the specificity of 0.955. See Table 5 and Figure 2 for additional details.

Discussion

As medical technology develops, interventional therapy as a surgical treatment without laparotomy has become widely acknowledged by medical professionals for its clinical efficacy for middle-advanced liver cancer. However, cellular and humoral immune function is often impacted in patients who receive this treatment. Furthermore, the use of chemotherapeutics increases the risk of nosocomial infection. Our study showed that 37 out of 325 patients had postoperative infections, indicating an infection rate of 11.38%. We isolated 51 strains of pathogenic bacteria from the infected patients (Gram-negative bacteria accounted for 74.51%). Notably, Escherichia coli (27.45%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19.61%) were the most commonly observed bacteria. There are some differences in the proportion and species of strains between our findings and those of the prior reseach,13 which may be due to the heterogeneity of the study patients and the composition of nosocomial pathogens. Pulmonary infection was identified as the main type of infection in the 37 infected patients. This is potentially because the function of respiratory muscles and ciliary movement, as well as the elasticity of the airway wall and lung tissue, weaken with age, resulting in difficulty excreting secretions. Generally, patients cannot forcefully cough and breathe deeply due to an increased pain after chemotherapy, which results in retention of pulmonary secretions and further increases the risk of infection.14 This finding also highlights the need to actively take preventive measures in clinical practice in order to reduce the possibility of infection based on a patient’s condition.

The T lymphocyte subset plays an important role in the immune mechanism. The CD4+ cells can directly kill or damage tumor cells, while CD8+ T cells function to suppress the immune response of the body.15 Under normal physiological conditions, CD4+ and CD8+ cells exist in a dynamic balance. A previous study found that the T lymphocyte subset level in patients infected after undergoing cesarean section was in a state of disorder, which suggests that the detection of T lymphocyte subsets plays a positive role in the prevention and treatment of postoperative infection.16 To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the changes in T lymphocyte subset levels in patients with infection after liver cancer interventional surgery. We found that the CD3+, CD4+ and CD4+/CD8+ levels were significantly decreased while the CD8+ level was greatly increased in the patients, indicating that immune function was decreased in both infected and non-infected groups. These changes may be due to the inhibition of immune function caused by surgical trauma and stress, or postoperative immune dysfunction resulting from abnormal anti-tumor function in patients with liver cancer.17, 18, 19, 20 Furthermore, the CD3+, CD4+ and CD4+/CD8+ levels were lower, and the CD8+ level was higher in the infection group compared to the non-infection group. These results are consistent with those of the previous studies about changes in T lymphocyte subsets in patients with postoperative infection. We believe that this difference may occur due to the fact that the postoperative infections lead to more severe disturbance of the immune function. This result also suggests that medical professionals should pay attention to changes in T lymphocyte subsets in patients receiving liver cancer interventional therapy, so as to provide timely and effective prevention and control measures.

Toll-like receptors form the major family of pattern recognition receptors for innate immune responses. There are 11 subtypes found in humans, among which TLR2 and TLR4 are considered to be closely related to the development of liver cancer. It has been reported that TLR2 and TLR4 protein levels are significantly increased in liver cancer tissues compared with normal liver tissues.20, 21 Toll-like receptors are reported to be closely related to infection and inflammatory response. They are activated in response to infection or inflammation, which promotes the expression of their downstream pro-inflammatory factors and alters inflammatory signaling cascades.22 There is also evidence suggesting that TLR2 mainly recognizes Gram-positive bacteria while TLR4 – Gram-negative bacteria.23 Our study demonstrated that the expression levels of TLR2 and TLR4 in the non-infection group decreased after surgery, while the levels in the infection group increased compared to those before surgery. These results suggest that surgical treatment can improve TLR2 and TLR4 levels in patients. However, for patients with postoperative infection, the occurrence of infection results in a state of inflammatory response, which increases TLR2 and TLR4 levels. The results also suggest that changes in TLR2 and TLR4 levels are of great clinical significance to postoperative infection. The value of postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels for predicting postoperative infection was analyzed using ROC curves, and the results indicated that postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels have clinical value with high sensitivity and specificity. Hence, we consider TLR2 and TLR4 levels after TACE to be useful biomarkers for evaluating postoperative infection in patients with liver cancer.

Innovations

This study has the following innovations and advantages. Firstly, changes in the T lymphocyte subset level and positive rates of TLR2 and TLR4 in patients with infection after liver cancer interventional therapy were investigated for the first time. Secondly, we used patient blood samples for the analyses, which were easy to collect, involved simple procedures, and had high compliance.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, without further dynamic observation of each indicator, it is difficult to assess the relationship between the above indicators and patient prognosis. Second, this is a single-center study with a small sample size. Lastly, the constituent ratios of age, gender, age, BMI, pathological type, Child–Pugh classification, clinical stage, etc. differed among the enrolled patients, and we did not conduct further subgroup analyses of patients with different characteristics. Therefore, further studies are needed to address these issues.

Conclusions

After interventional therapy for liver cancer, the main infection sites were identified as the lung and abdomen, with Gram-negative bacteria accounting for the majority of infections. Furthermore, the results indicated that the T lymphocyte subset level abnormally changed in patients with infection and that TLRs are closely related to the occurrence and development of postoperative infection. Postoperative TLR2 and TLR4 levels could be used as an auxiliary parameter to assess the postoperative infection risk.