Abstract

Background. Frailty syndrome and cardiovascular diseases are closely related because of the shared physiological pathway of chronic, low-intensity inflammation. Frailty syndrome may be an adverse factor in the prognosis of patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Objectives. To assess the influence of frailty syndrome on patient prognosis after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Materials and methods. The study was conducted at the Clinic of Cardiac Surgery in Katowice and involved 180 patients (56 women, 31.11%) over 60 years of age who qualified for CABG surgery. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) was used to assess frailty syndrome and the The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire was used to assess quality of life. Statistical analysis was performed using R software.

Results. Frailty syndrome was diagnosed in 42 patients (23.3%), including 24 men and 18 women. More than 1/3 of patients had complications during or after surgery, including 34.6% of patients without frailty syndrome and 28.6% of patients with frailty features. All of the complications occurred in 57 (31.6%) patients. Early complications accounted for 89.5% of all events – 93.3% of which occurred in patients without frailty syndrome and 75% in patients with frailty features (p = 0.289).

Conclusions. More than 1/3 of patients experienced complications during or after the CABG procedure. Early postoperative complications accounted for almost all of the adverse events in patients with frailty. However, frailty syndrome was a poor predictor of rehospitalization.

Key words: quality of life, coronary artery bypass grafting, frailty syndrome

Background

The most common group of diseases in elderly patients is cardiovascular system diseases (CVDs). According to data from the National Registry of Cardiac Surgery Procedures (KROK), about 12,000 coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) procedures were performed in cardiac clinics throughout Poland in 2016.1

The classical CABG method uses extracorporeal circulation to provide optimal operating conditions; however, this method may cause complications such as ischemic stroke, myocardial ischemia, deterioration of kidney function, and respiratory failure. Cannulating the myocardium and aorta and clamping the ascending aorta could result in the release of embolic material, potentially endangering the patient’s life. Extracorporeal circulation also significantly burdens maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, which can lead to early neurological complications.2

Frailty syndrome is characterized by a decrease in immune reserves, resulting from the reduced capacity of various systems and organs, ultimately leading to the collapse of homeostasis, disturbances in organ function, and increased morbidity and mortality in older people. Factors known to contribute to the occurrence of frailty syndrome include old age, visual impairment, impairment of cognitive functions, impaired gait and balance, weakness of the limbs, and the occurrence of comorbidities.3

Although frailty syndrome is not synonymous with old age, which is often accompanied by multiple diseases, any bodily dysfunction is a risk factor for frailty syndrome and may lead to disability. Insufficient physiological reserves of the organs increase the likelihood of adverse consequences, such as complications resulting from minor injuries and surgery, which can lead to death.3, 4, 5

Frailty syndrome and CVD are pathophysiologically closely related because of the common biological pathway of chronic, low-intensity inflammation. A diagnosis of frailty syndrome among patients who are qualified for CABG may quicken the healing process. Implementing appropriate measures customized to a patient’s condition, including comprehensive geriatric and psychological care and rehabilitation, can improve the recovery period and reduce the number of adverse events.6

A significant problem in frailty syndrome is the coexistence of other diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, diseases of the genitourinary and digestive systems, and neurological diseases. These comorbidities have a large impact on the treatment process and patient recovery.

Elderly patients with a high surgical risk may experience improvement in their condition and quality of life after the procedure; however, there is always the possibility of complications, such as bleeding, stroke and respiratory or renal failure.7

The occurrence of frailty syndrome may be an adverse factor for the prognosis of patients with CVD. Mortality, a prolonged length of hospitalization and difficulties in postoperative wound healing are the most common complications after coronary artery bypass procedures. Appropriate diagnosis and therapy for treating frailty syndrome in elderly patients can influence the therapeutic team’s actions and selection of the most beneficial treatment for the patient.8

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of frailty syndrome on the prognosis of patients after coronary bypass surgery.

Materials and methods

Study design and settings

This observational, prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Clinic of Cardiac Surgery in Katowice, Poland, from November 1, 2018 to January 30, 2020. The patient group consisted of 180 patients, 56 of which were women (31.1%).

The mean patient age was 69.34 years (standard deviation (SD) ±6.16) and the age range 60–84 years. All patients met the requirements for CABG in extracorporeal circulation and had undergone 2 or more bypasses.

Study participants and selection

The inclusion criteria were being over the age of 60, qualifying for CABG, consenting to participate in the study, and having a mental state that enabled contact with the team and understanding the questionnaire items. The exclusion criteria were simultaneous qualification for CABG and another procedure such as valve replacement, active cancer and refusal to participate in the follow-up visit.

Stages of the study

This study was conducted in 2 stages. The first stage consisted of a clinical interview, collection of demographic data, anthropometric measurements, and completion of standardized questionnaires. The second stage, which occurred 6 months ±2 weeks after the procedure, involved a follow-up visit that included a clinical history of the occurrence of any postoperative complications with a breakdown into cardiac and non-cardiac causes, repeated hospitalization, death, or other adverse events. The survey questionnaires were also repeated.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice (approval No. KNW/0022/KB/22518) on October 16, 2018. Before joining the study, participants were informed about the confidentiality of the study, their anonymity, the study goals, and the methodology. Patients were also informed that they had the option to withdraw at any stage of the study. Data collection and analysis were performed based on the ethical principles in the Helsinki Declaration. The research was not funded.

Research instruments

The Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI) was used to assess frailty syndrome which, in addition to physical dysfunctions, includes psychological and social determinants. The scale consists of two parts, A and B. The first part concerns sociodemographic information such as age, gender, marital status, education level, and country of origin. The second part consists of 15 questions relating to the occurrence of the main components of frailty. It is divided into 3 domains: physical, psychological and social. The total score range is 0–15 points. Frailty syndrome is recognized as a TFI score ≥5. The tool was developed by Gobbens et al. and is based on the concept of the frailty model.9, 10 Quality of life was assessed using the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire for the following domains: physical functioning (domain 1), psychological functioning (domain 2), social relations (domain 3), and environmental functioning (domain 4). The questionnaire comprises of 26 questions that enable the 4 above-mentioned domains to be analyzed, a self-assessment of a patient’s health condition and a determination of a patient’s perception of their quality of life. Each item in each domain is scored between 1 and 5 points. The maximum score is 20 points. The WHOQOL-BREF also includes items that are analyzed separately: question 1 (WHO1): an individual’s general perception of their quality of life; and question 2 (WHO2): an individual’s general perception of their own health. The scores for these individual items are in a positive direction (i.e., a higher number of points indicates a higher quality of life).11

Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables (i.e., expressed with numbers) were analyzed by calculating the mean, SD, median, quartiles, minimum, and maximum. Qualitative (i.e., non-numerical) variables were analyzed by calculating the number and percentage of each value.

Qualitative variables were compared between groups using the χ2 test (with Yates’s correction for 2 × 2 tables) or Fisher’s exact test. The values of quantitative variables were compared between 2 groups using the Mann–Whitney test. The quantitative variables for the 2 repeated measurements were compared using the Wilcoxon test for paired data. The Kaplan–Meier curves were compared using the log-rank (LR) test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to compare the predictive value for patients with frailty syndrome as well as the occurrence of complications and rehospitalization. Results were considered to be significant at p-value <0.05. All of the presented statistical analyses were performed using R software, v. 4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).12

Results

The mean patient age was 69.34 years. Most patients (74.4%) were married or in a partnership. The majority (61.1%) of patients had a secondary education, and the next largest group consisted of patients with a postsecondary education (29.4%). The mean annual household income was 21.612–25.200 PLN in 47.2% of patients. Although more than 50% of patients had 2 or more diseases, 73.9% of them assessed their lifestyle positively in terms of their health. On the New York Heart Association (NYHA) scale, most of the patients were in the first class of disability. Additional details of patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Frailty syndrome was diagnosed in 42 patients (23.3%); 54.8% of patients in this subgroup were men and 42.9% were women. The mean age of women with frailty syndrome was 73.5 ±6.4 years; for men, it was 70.17 ±5.3 years. Most patients (80%) with frailty syndrome were widows or widowers. Almost 75% of patients considered themselves to be healthy (73.9%). The mean overall TFI score was 2.79 ±1.97 for women and 2.15 ±1.91 for men. There were statistically significant differences in the total TFI score and in the social components between the sexes (p = 0.025 and p = 0.002, respectively), with higher scores for women. There were no significant differences in the remaining domains. Table 2 presents the mean score for each subscale of the TFI scale for the overall patient group.

The logistic regression model (Table 3) showed that important independent predictors of frailty syndrome included separation or divorce (the chance of frailty syndrome increased 10.416 times compared to living with a spouse/partner) or widowhood (the chance of frailty syndrome increased 6.678 times compared to living with a spouse/partner) and an unhealthy lifestyle (the chance of frailty syndrome increased 10.982 times compared to having a healthy lifestyle).

Before the procedure, all patients had coexisting diseases. The most frequent diseases were arterial hypertension at 60% (69% of patients with frailty and 57% of patients without frailty syndrome), diabetes mellitus at 30.6% (38.1% of patients without frailty syndrome and 28.5% of patients with frailty syndrome) and gastrointestinal diseases at 15.6% (21.4% of patients without frailty syndrome and 13% of patients with frailty syndrome). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups.

A follow-up visit took place 6 months after the procedure. Follow-up was performed for 170 of the patients from the previous group (8 (4.4%) did not attend and 2 (1.1%) died). More than 1/3 of patients (34.6% of patients without the frailty syndrome and 28.6% of patients with frailty features) had complications during or after the procedure. All of the documented complications occurred in 57 (31.6%) respondents. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p = 0.1). Early complications accounted for 89.5% of all events, including 93.3% in patients without frailty syndrome and 83.3% in patients with frailty syndrome (p = 0.289). Table 4 presents the different types of complications.

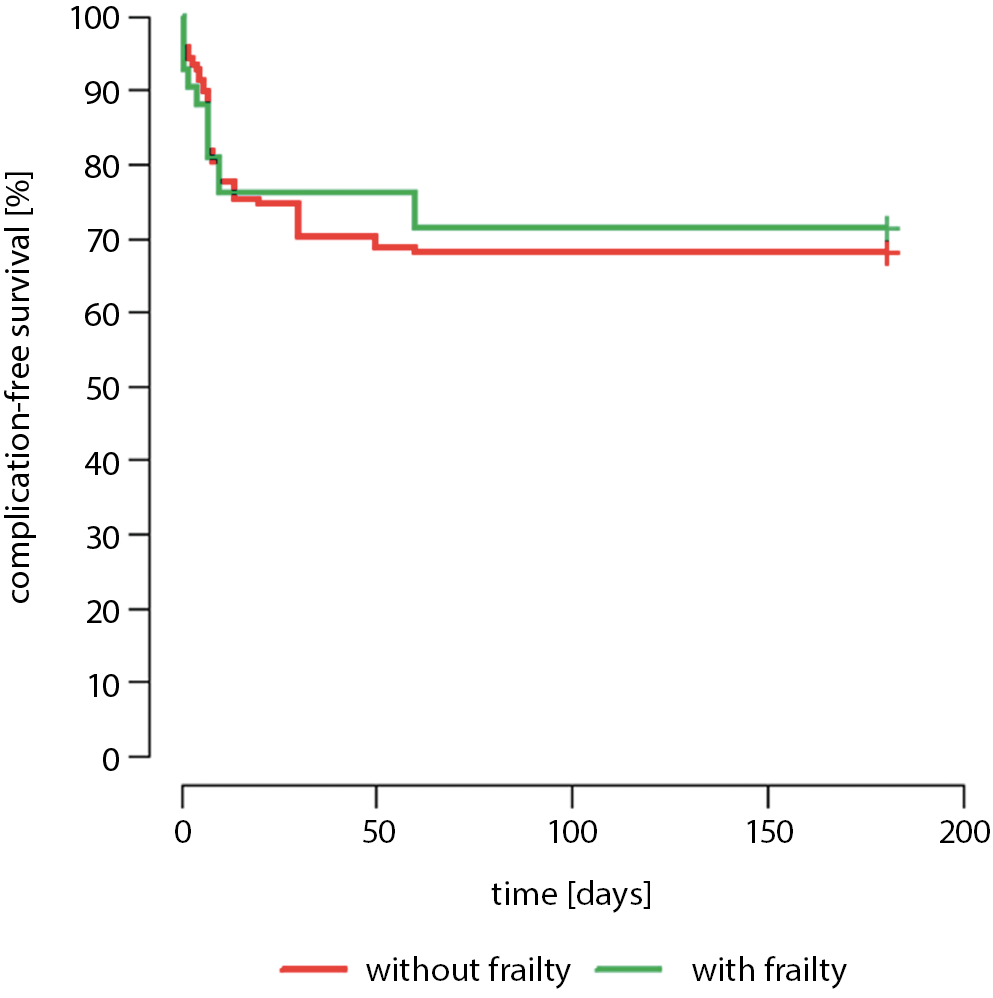

Twenty-three patients (13.5%) were rehospitalized, which included 4 patients with frailty syndrome and 19 healthy people (p = 0.737). Eight patients were rehospitalized for cardiac issues (36.5% of all hospitalizations, including 2 patients with frailty syndrome). There were no statistically significant differences between the occurrence of complications and hospitalization and the gender of the patients. On average, patients were discharged 1 week after the surgery. The complication-free survival rates between patients presenting with and without the symptoms of frailty syndrome showed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.734). The results are presented in Figure 1.

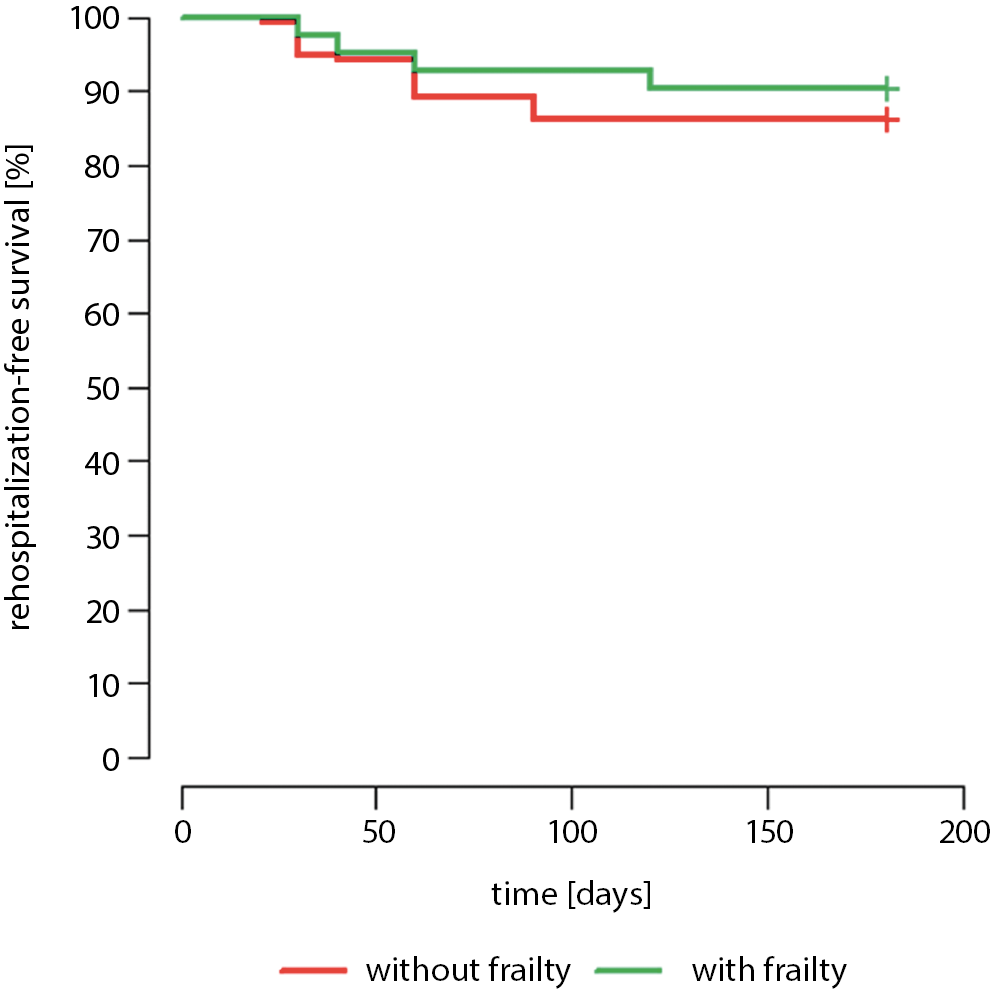

Similar results were observed for patients in both groups who were not rehospitalized. The p-value of the log-rank test was >0.05, indicating that the survival curves for the 2 groups did not differ significantly (p = 0.472). These data are presented in Figure 2.

In the subjective evaluation of satisfaction with the procedure and hospitalization, patients without frailty syndrome reported higher satisfaction compared to those with frailty syndrome (78% compared to 65%, p = 0.002). Dissatisfaction and moderate satisfaction were expressed by 35% of patients with frailty syndrome who were surveyed.

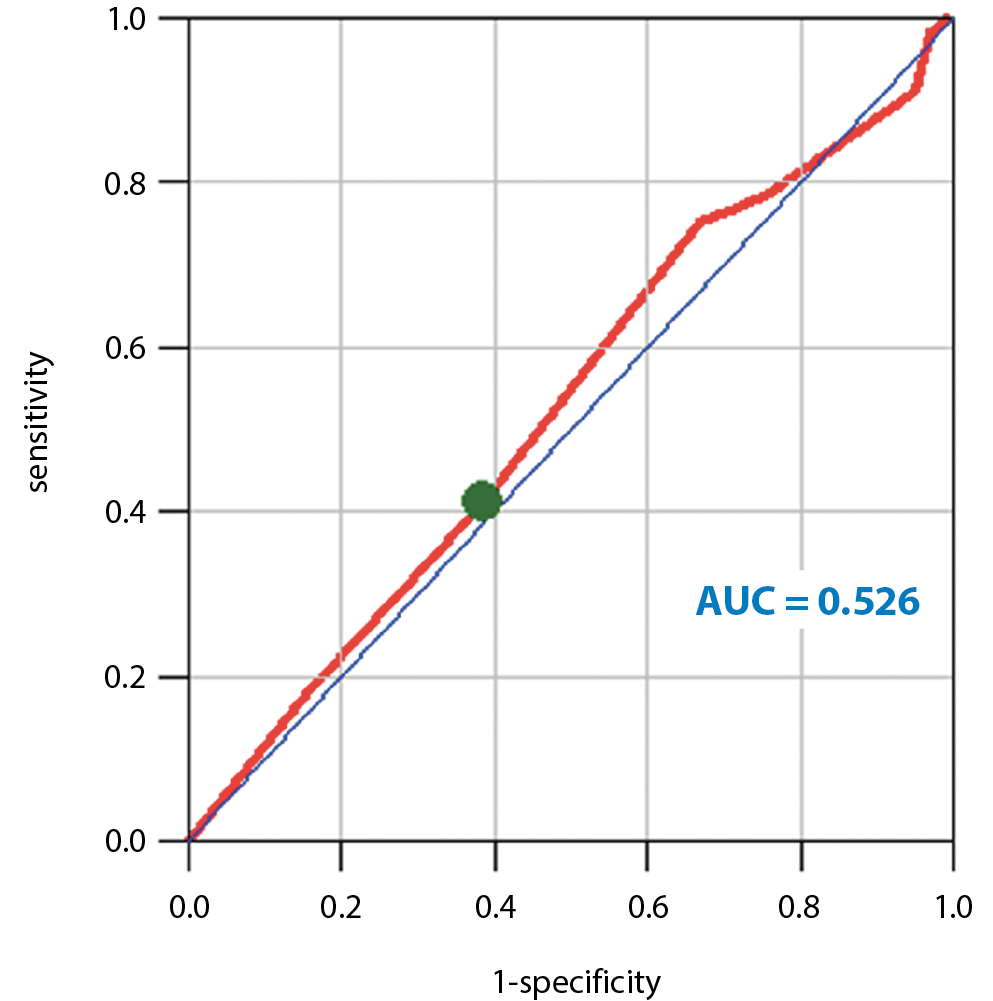

Frailty syndrome diagnosed in patients before surgery was not a significant predictor of complications: the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.526. The optimal cut-off score for the TFI before surgery was 2 points. When it was more than 2 points, complications could be expected. The sensitivity was 41.1% and the specificity was 61.3%. The ROC curve is shown in Figure 3.

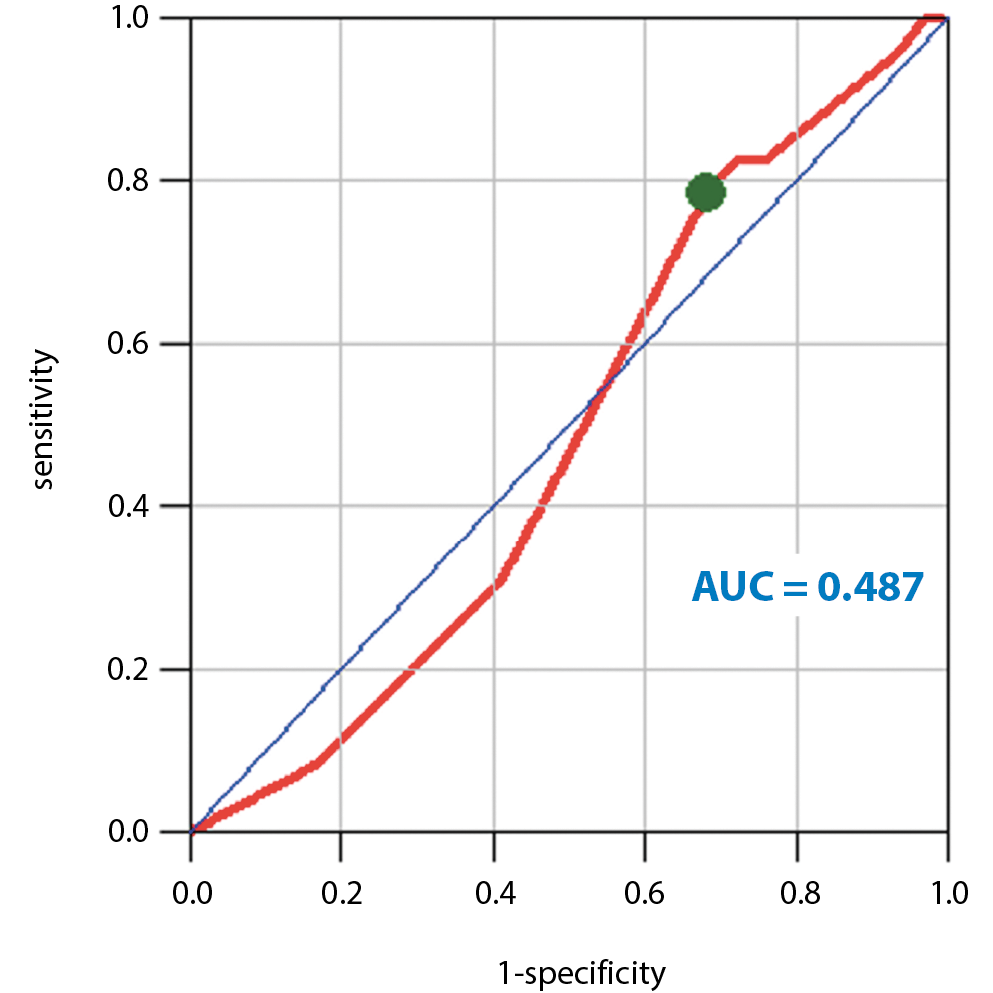

The AUC was 0.487 for TFI before the procedure, which means it was a very weak predictor of the occurrence of rehospitalization. The optimal cutoff point for the TFI before surgery in this case was 3 points.

For patients with more than 3 points, rehospitalization was required. The sensitivity was 78.3% and the specificity was 31.9%. The data are presented in Figure 4.

After the surgery, there were statistically significant changes in nearly every dimension of the patients’ mental and physical health. The physical components of frailty were more intense after CABG (p = 0.007).

In patients with diagnosed frailty syndrome, in addition to deterioration in independence in performing everyday activities, there were significant changes in their quality of life. In all areas of life, as well as in the perception of quality of life, these patients reported lower scores. The data are presented Table 5.

Discussion

Frailty syndrome can cause many complications. A meta-analysis conducted by Rockwood et al., which included more than 68,000 individuals, showed that patients with frailty and pre-frailty are at risk for a higher number of falls, frequent hospitalizations, longer stays in the hospital, and more postoperative complications. The authors also demonstrated links between frailty syndrome and imbalance, inferior lower limb muscle control, difficulties in self-service activities, and higher mortality rates. In our research, patients with frailty syndrome did not show prolonged hospital stays. The results revealed that frailty syndrome is a weak predictor of the incidence of hospitalization among this group of patients.13

In a three-year prospective cohort study of patients ≥65 years of age undergoing general surgery, the authors drew the following conclusions. In the group of 326 hospitalized patients, frailty syndrome was diagnosed in 38.9% of patients. On admission, frailty patients received higher American Association of Anesthesiologist (ASA) grades, with grade 1 (ASA I) indicating a healthy patient and grade 4 (ASA IV) indicating a patient with a severe systemic disease that is life-threatening. Hospital complications occurred in 26.7% of patients in this group and the mortality rate was 30%. Patients with frailty syndrome also had higher Failure to Rescue (FTR) results; the higher the rate, the lower the chance of a successful operation. It was determined that frailty syndrome was also a predictor of FTR. The researchers stated that an important element in patient case is the use of indicators to assess frailty syndrome. According to the analysis, frailty syndrome increases the risk of intraoperative complications and patient’s death three-fold among elderly patients.14

Similar conclusions were drawn by Han et al. in a study of 2278 patients. They assessed the risk of adverse events after surgery with regard to the presence of frailty syndrome features. It was revealed that the risk of postoperative complications was higher in patients with frailty syndrome than in those with no frailty symptoms. Our results are generally consistent with those of Khan and Han: although frailty syndrome did not cause increased mortality or rehospitalization, almost all patients with frailty had early hospital complications.15

Birkelbach et al. evaluated the impact of frailty syndrome on the risk of postsurgical complications. Patients were classified according to their frailty using the five-point Fried Frailty Index, where a score of 3 or more points indicates frailty and 2 or fewer points indicates pre-frailty. The occurrence of postoperative complications was evaluated until patients’ discharge from the hospital. Of the 1186 participants, almost half (46.9%) were in the pre-frailty group and 11.4% were diagnosed with frailty syndrome. In both groups, there was a higher risk of complications and the postoperative hospital stay was longer compared to patients without frailty. The incidence of adverse events was twice as high in patients with diagnosed frailty syndrome and pre-frailty features. In our research, frailty syndrome was diagnosed in 23% of the patients and the mean TFI score was about 3 points, which suggests that most of the patients were classified as pre-frailty, although we did not test or evaluate this group. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with and without frailty syndrome and the incidence of postoperative complications.16

In their work, Rothenberg et al. examined the effect of frailty syndrome in patients after scheduled surgery after unplanned readmission. Frailty was assessed using Risk Analysis Index (RAI), including physical dysfunctions (renal failure, dyspnea, etc.) and cognitive status. The TFI was also used, which included additional social and psychological domains. They evaluated the data of 417,840 patients using a retrospective cohort design. More than half of patients that were hospitalized (59.2%) after surgery were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days due to complications. Most often, these patients were women or had diagnosed frailty syndrome. When the frailty data were analyzed, the risk of unplanned readmission doubled. The results demonstrated that frailty syndrome is an important risk factor for readmission after a planned outpatient procedure due to complications. Screening for frailty syndrome may affect the development of interventions to reduce unplanned readmissions and treatments. In contrast to our studies, 1/3 of patients had postoperative complications and there were no significant differences between gender groups regarding the occurrence of unplanned events.17

This is important because it concerns the same study group as in their own research. After cardiac surgery, patients with frailty syndrome stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) longer and were more likely to have complications compared to those without frailty syndrome. On average, the stay in the ICU was prolonged from 28 h to 54 h. There were no significant differences in hospitalizations between the groups of patients with and without frailty syndrome. The average hospital stay was 1 week.18

Tran et al. performed four-year follow-up of patients with increased mortality. Frailty syndrome, which was diagnosed in 22% of patients (n = 40,083) at four-year follow-up, was associated with higher postoperative mortality compared to healthy individuals. In this group, there were greater differences in the survival of patients between 40 and 74 years of age than in patients over 85 years of age. In our research, the follow-up visit took place 6 months after the surgery and the mortality rate was very low.19

In a Brazilian study, the research on frailty syndrome was included in the holistic nursing care of a patient. Of all of the patients included in this study, 93.6% had memory impairment, 93.6% had physical mobility problems, 82.1% showed general fatigue and weakness, and more than 50% were diagnosed with self-care deficits.20

Similar conclusions to our own research were drawn by Uchmanowicz et al. Frailty syndrome was diagnosed in 64.8% of patients with heart diseases who were predisposed to rehospitalization. It was also noted that physical and psychological aspects were important components.21

Different conclusions were drawn by Lupon et al. In their study based on 622 patients, 39.9% of whom had diagnosed frailty syndrome, frailty was not a prognostic factor for rehospitalization, but it was for higher mortality in patients with heart failure. In our study, frailty syndrome was not a prognostic factor for mortality or rehospitalization. This could be due to the lower mean age of the patients enrolled in our study compared to those in previous studies by different authors.22

Limitations

The population in this study exhibited a relatively low burden of frailty and was relatively young (mean age = 69 years old). The prevalence of frailty syndrome is generally higher in people over the age of 80. This could represent a bias in the present study and may have influenced the findings. This study did not investigate the impact of comorbidities on prognosis.

Conclusions

More than 1/3 of patients had complications during or after the procedure. There were more early postoperative complications in patients with frailty syndrome. There were no statistically significant relationships between the occurrence of complications and hospitalization and the gender of patients. Frailty syndrome was a poor predictor of rehospitalization. Patients without frailty syndrome expressed higher satisfaction in the subjective evaluation of the procedure and hospitalization.