Abstract

Background. The pathogenesis of myopia remains unclear. Both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the disease progression. Reasons including reduced physical activity (PA) and low-grade intraocular inflammation may be involved in the development of myopia.

Objectives. To analyze the levels of irisin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and other intraocular cytokines in aqueous humor of high myopia patients, and to evaluate the roles of PA and inflammation in developing myopia.

Materials and methods. We collected aqueous humor samples from patients with axial length (AL) over 26 mm (n = 35) or shorter than 25 mm (n = 38) during cataract extraction surgery. Samples were assayed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for irisin and a multiplex immunoassay kit for BDNF, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8 and IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

Results. Irisin levels in the aqueous samples of the highly myopic eyes were significantly higher than in the control group (p = 0.027). The BDNF levels of the highly myopic group were significantly lower than in the control group (p = 0.043). Median level of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) for highly myopic group (2.035 pg/mL) was statistically significantly higher than in the control group (0.750 pg/mL) (U = 210.5, Z = −4.495, p < 0.001). Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) level in the aqueous samples of the highly myopic group was significantly lower than in the shorter AL group (p = 0.049). Interleukin 6, IL-8 and IL-10 levels were not significantly different between the 2 groups (p = 0.501, p = 0.059 and p = 0.192, respectively). Tumor necrosis factor α levels could only be detected in 30 samples and median levels in the 2 groups were not statistically significantly different (U = 99, Z = −0.482, p = 0.650). No correlation was found between IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNF-α, and the AL (p > 0.05). Irisin was positively correlated with AL (p = 0.028, r = 0.287). The BDNF was negatively correlated with AL (p = 0.040, r = −0.246). Interleukin 1ra was negatively correlated with AL (p = 0.038, r = −0.276). There was also a correlation between LIF and AL (p < 0.001, r = 0.486).

Conclusions. Higher irisin level in high myopia group opens a new direction to discover the relationship between PA and myopia. The decreased BDNF in high myopia group probably demonstrates the connection between myopia and neurodegenerative disease.

Key words: physical activity, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, myopia, irisin, neurodegenerative disease

Background

Myopia is one of the leading causes of visual impairment worldwide. There are many patients with myopia who experience a progressive change over their entire lifetime, including elongation of the axial length (AL), and degenerative changes of the retina and choroid. Many population-based studies have shown that high myopia is the 2nd reason for visual disability in Asia.1, 2 The prevalence of myopia is predicted to increase to 49.8% by 2050, with 9.8% suffering from high myopia.3 The risk increases along with the increased diopters of myopia.4

Currently, the pathogenesis of this disorder remains unclear. Both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the disease progression. It has been speculated that lifestyle changes such as reduced physical activity (PA), reduced time spend outdoors and more indoor work might be the reason of myopia progression.5 Irisin,6 as an exercise-induced myokine, is secreted into the circulation after proteolytic cleavage from fibronectin-type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5). The physiological function of irisin is to convert white adipose tissue to brown, which increases energy expenditure.6 Physical activity is well-known as a protective lifestyle feature against type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular diseases, cancer, dementia, and depression.7 The protective role of PA against myopia has also been an area of interest in recent years. The mechanism of the positive effect of PA has not been discovered, but theories include increased choroidal blood flow and thickness.8 We hypothesized that irisin, as an exercise-induced myokine, may be involved in the relationship of PA and myopia progression.

Although irisin was first found in skeletal muscles,6 recent studies have proved it exists in various tissues, including smooth muscle tissue.9 As early as the 1980s, close-up work was considered to be one of the important risk factors for the development of myopia. The ciliary muscle is related to the occurrence and development of myopia according to the ocular accommodation mechanism. Study of the relationship between irisin level and axial myopia may help to understand whether the ciliary muscle is involved in this pathological process and its mechanism.

Physical activity has also been shown to improve brain-related outcomes, in particular neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD)10 and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).11 High myopia-related retinal atrophy is known as a type of neurodegenerative change. Neurotrophins play a major role in the growth and development of neurons. One of these neurotrophic factors is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). In addition, Young et al.12 identified FNDC5 as an important regulator of BDNF. The goal of our study was to shed light on FNDC5/irisin and its role in the beneficial effects of PA on myopia prevention and its potential application in neurodegenerative disorders deregulating BDNF.

On the other hand, several studies showed that sclera stretching or staphyloma development can be monitored during treatment and follow-up of some inflammatory ocular disease such as Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease.13 According to those studies, it is possible that chronic inflammation in the retina or choroid could induce stretching of the sclera and axial elongation. It has been demonstrated that the levels of drugs or cytokines are positively correlated between the aqueous and vitreous fluid.14, 15 In order to prove that there is a connection among myopia, PA and subclinical inflammation, we decided to collect aqueous humor from senile cataract extracts in normal and long AL eyes in our hospital from March to October 2019.

Objectives

To analyze the levels of irisin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and other intraocular cytokines in aqueous humor of high myopia patients, and to evaluate the roles of PA and inflammation in developing myopia.

Materials and methods

Study design

Seventy-three eyes from 73 senile patients with cataract were studied from March to October 2019. The inclusion criterion was an uneventful cataract surgery. Eyes with glaucoma, uveitis, zonular weakness, previous trauma, previous intraocular surgery, or fundus pathology were excluded from the study. Patients with diabetes mellitus, using glucocorticoids and patients with autoimmune diseases were excluded. We used the IolMaster 500 (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) to exam the AL, so that we could recruit patients and divide them into 2 groups (longer AL group with AL > 26 mm (35 eyes, 35 patients) and shorter AL group with AL < 25 mm (38 eyes, 38 patients)).

Sample collection

We administered to the patients Oxybuprocaine Hydrochloride Eye Drop (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) 4 times every 5 min before the surgery for local anesthesia. Eyelids and the surrounding skin were swabbed with povidone iodine. Samples of aqueous humor (90–120 μL) were aspirated by inserting a 29-gauge needle through the corneal paracentesis into the anterior chamber before surgery. Samples were immediately stored at −80°C until sample analysis.

Irisin analysis

Samples were harvested and assayed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for irisin (Irisin ELISA Kit; Beijing Dongge Boye Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China), and were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The stop solution changes the color from blue to yellow and the intensity of the color is measured at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer. In order to measure the concentration of irisin in the sample, the Irisin ELISA Kit includes a set of calibration standards. The calibration standards are assayed at the same time as the samples and allow the operator to produce a standard curve of optical density (OD) compared to irisin concentration (Figure 1). The concentration of irisin in the samples is then determined by comparing the OD of the samples to the standard curve.

Other cytokines analysis

We simultaneously analyzed a selection of 7 cytokines (BDNF, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-8, IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)), using a multiplex immunoassay kit (ProcartaPlex; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). ProcartaPlex immunoassays are based on the principles of a ELISA, using 2 highly specific antibodies binding to different epitopes of 1 protein to quantitate all protein targets simultaneously using a Luminex 200™ System instrument (Luminex Corp., Austin, USA). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The standard curve was based on five-parameter nonlinear regression (Figure 1). Each cytokine concentration was then calculated by the curve.

Statistical analysis

The data was processed and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, v. 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). All data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Categorical data was compared between groups using χ2 test. Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to detect differences between the long AL group and normal group. Pearson’s correlation analysis was adopted to analyze the relations among the cytokines and the AL in our study. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

The preoperative distributions of age, gender and AL are summarized in Table 1. There was a significant difference of gender and no significant difference of age in the 2 groups. The globe AL of highly myopic eyes was significant longer (5.6 mm longer) than the control eyes (28.4 ±2.4 mm compared to 22.8 ±1.0 mm, p < 0.0001 (t-test)).

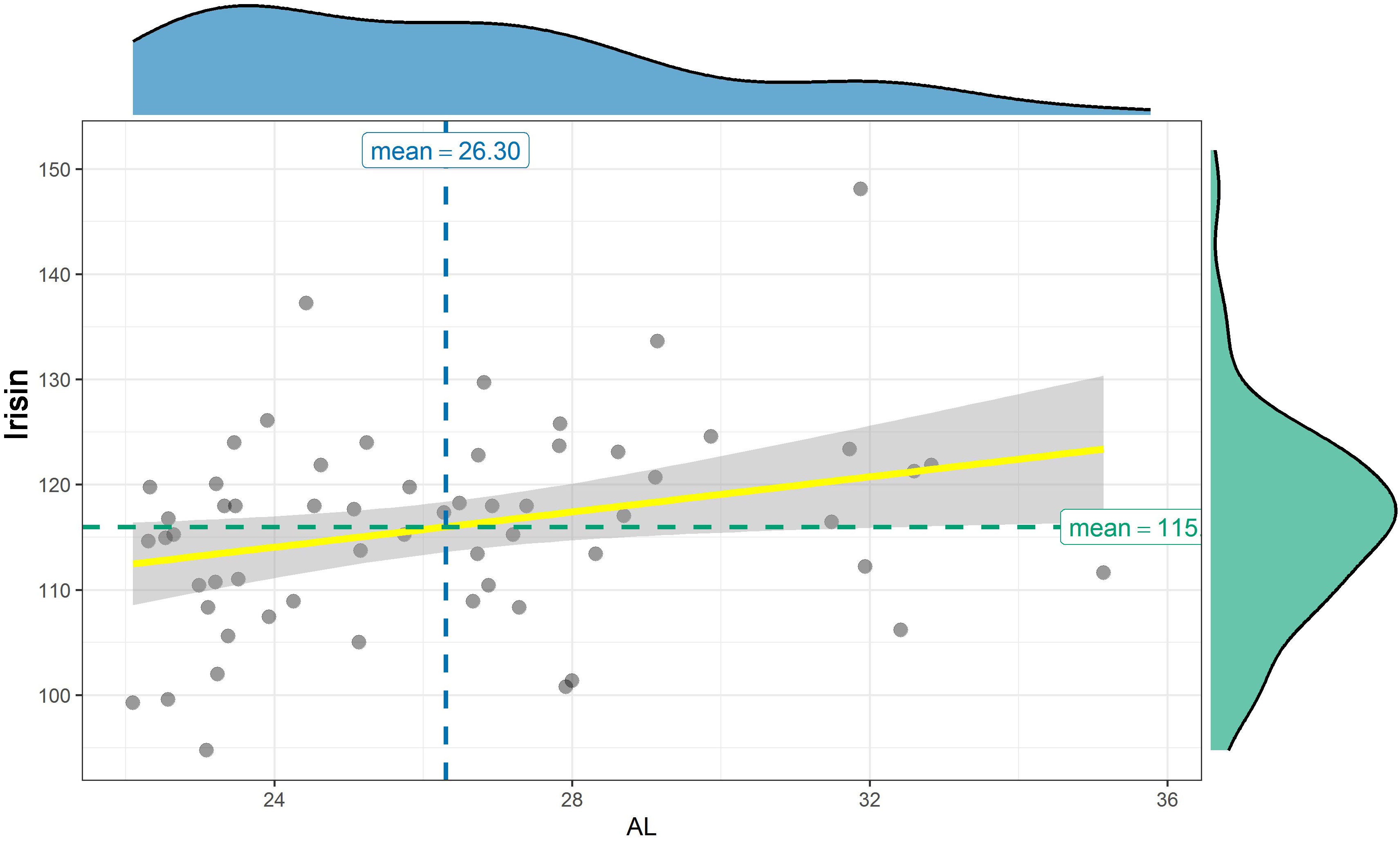

Irisin levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Student’s t-test revealed that irisin level in the aqueous samples of the highly myopic eyes was significantly higher than in the control group (p = 0.027). Mean values of irisin in the samples were 118.76 ±9.6 pg/mL in the AL > 26 mm group compared to 113.45 ±8.99 pg/mL in the AL < 25 mm group (Table 2). Furthermore, positive correlation was found between irisin and the AL (p = 0.028, r = 0.287) (Figure 2).

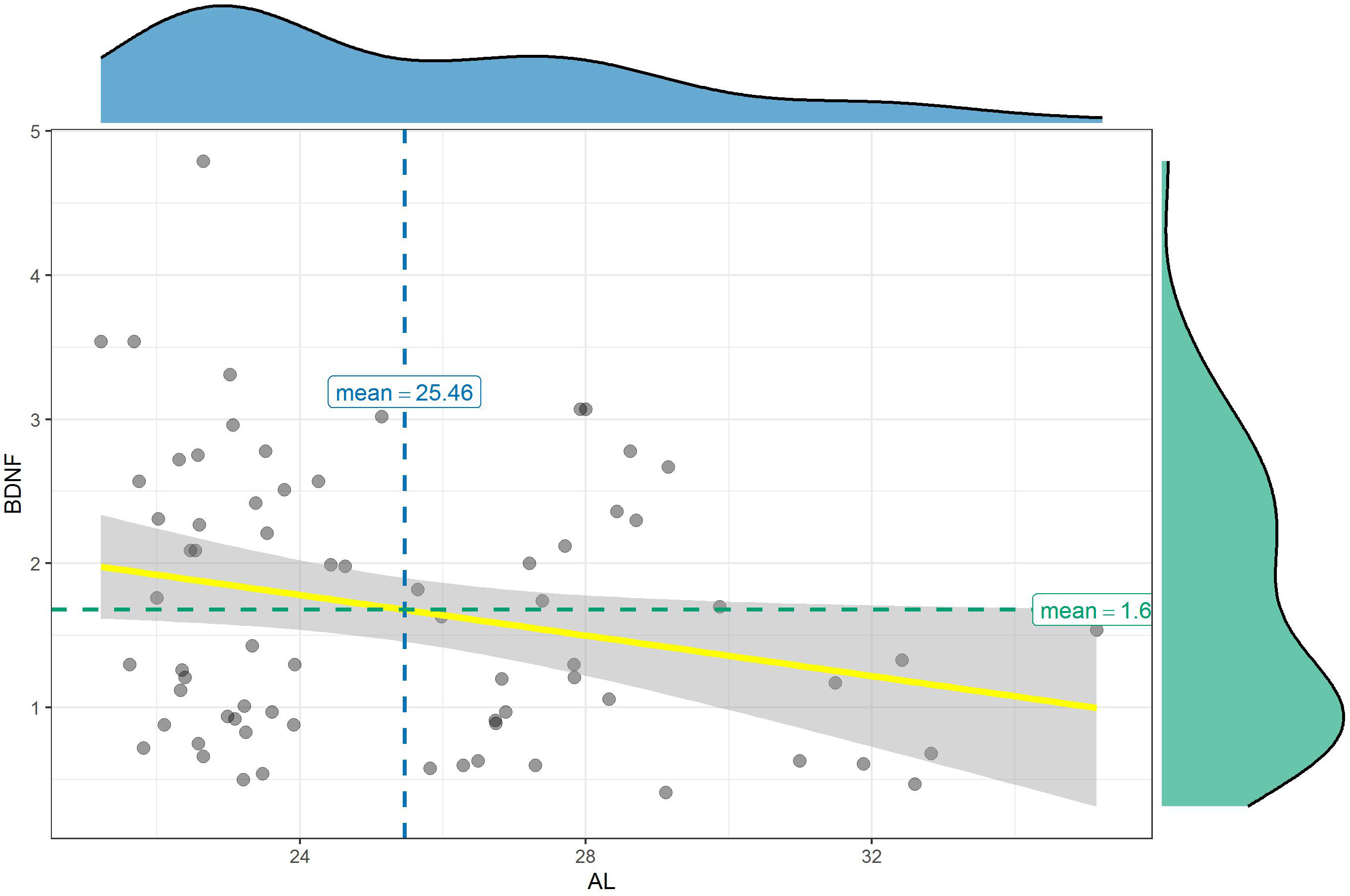

BDNF levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Student’s t-test revealed that BDNF level in the aqueous samples of the highly myopic eyes was significantly lower than in the control group (p = 0.043). Mean values of BDNF in the samples were 1.42 ±0.80 pg/mL in the AL > 26 mm group compared to 1.88 ±1.02 pg/mL in the AL < 25 mm group (Table 2). In addition, negative correlation was found between BDNF level and the AL (p = 0.040, r = −0.246) (Figure 3).

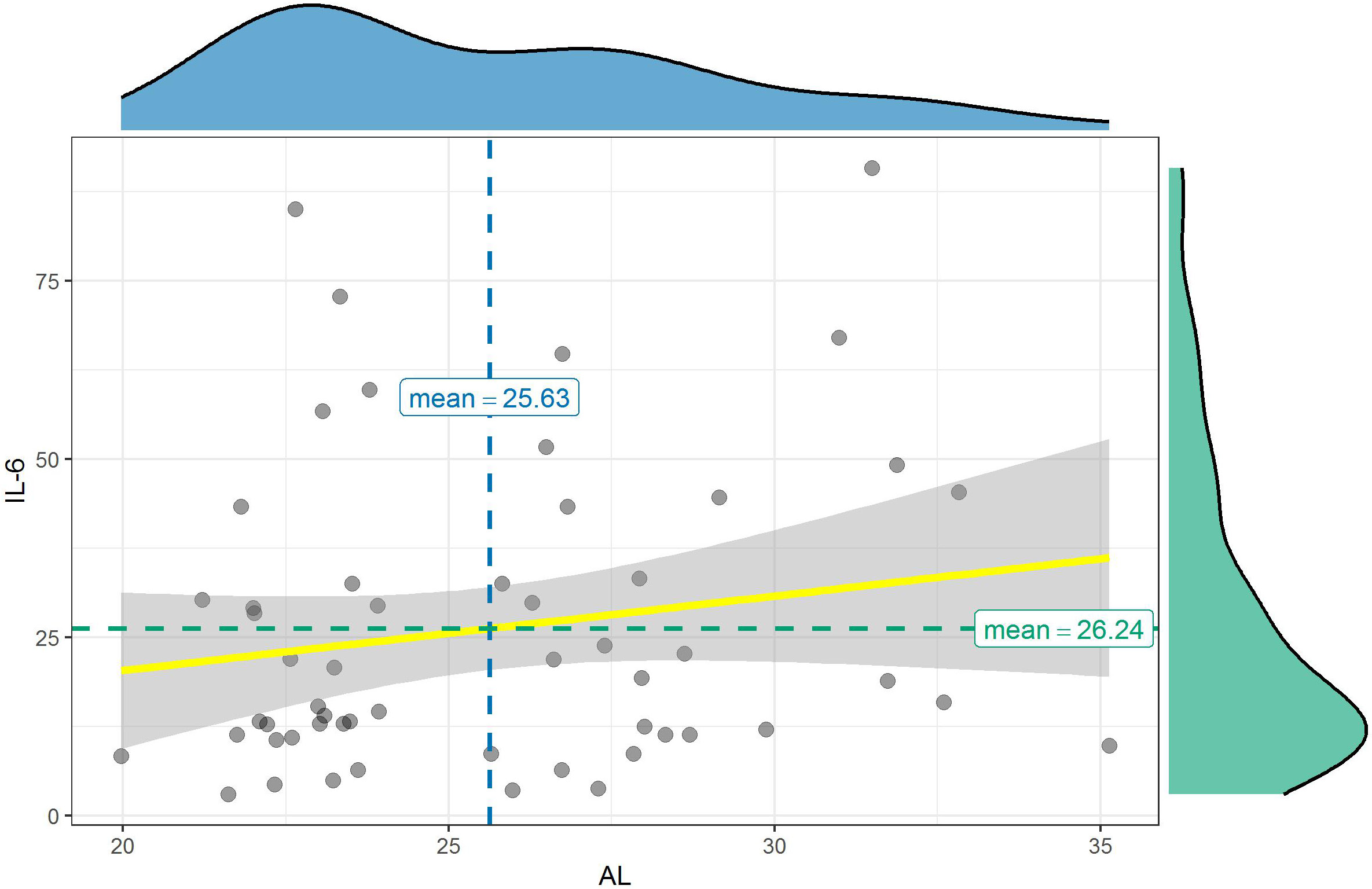

Interleukin 6 levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Median level of IL-6 for AL > 26 mm group (21.94 pg/mL) and AL < 25 mm group (14.29 pg/mL) was not statistically significantly different (U = 338, Z = −0.674, p = 0.501) (Table 3). No correlation was found between IL-6 level and the AL (p = 0.209, r = 0.172) (Figure 4).

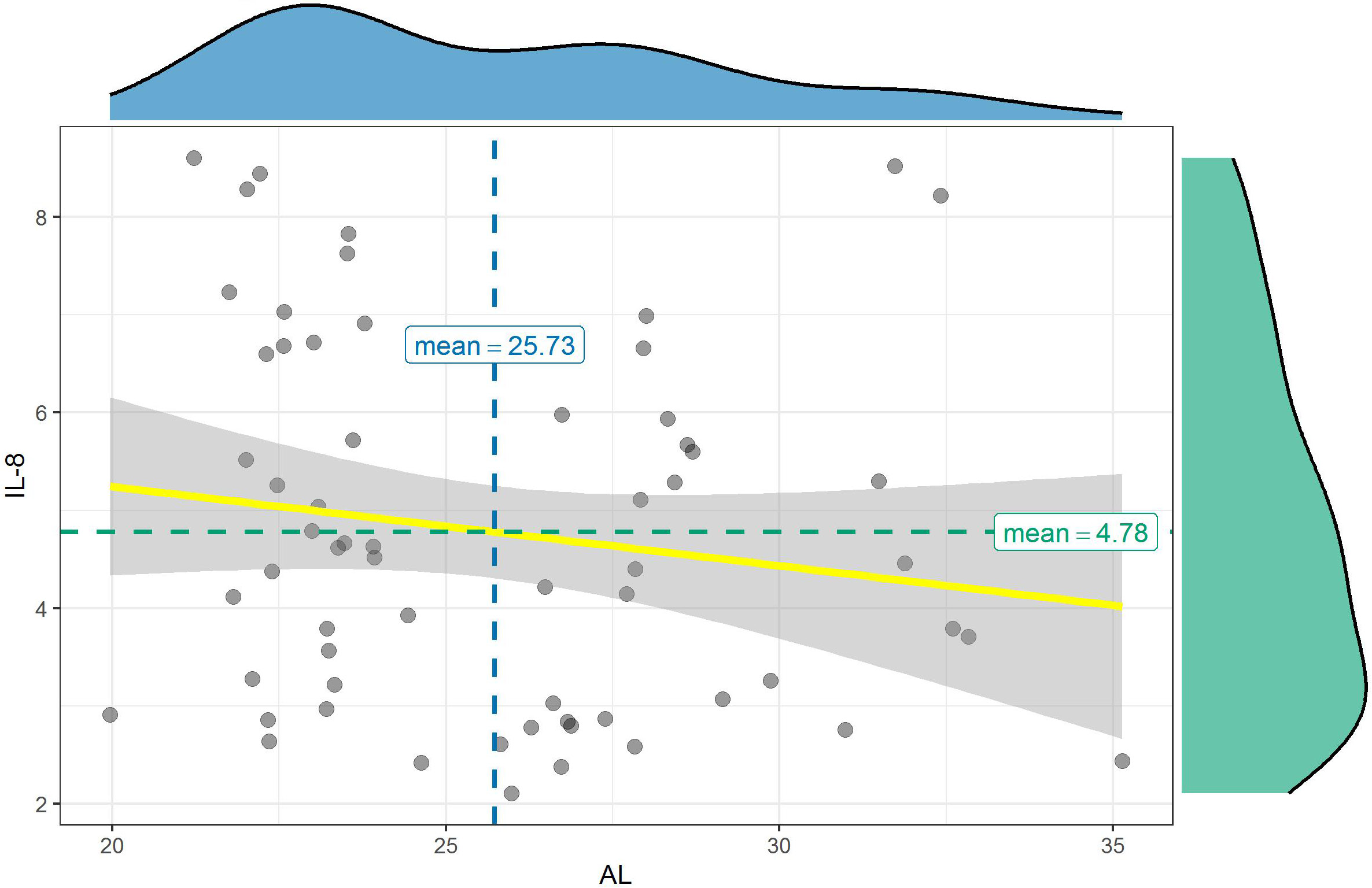

Interleukin 8 levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Student’s t-test showed that IL-8 level in the aqueous samples of the 2 groups presented no significant difference (p = 0.059). Mean values of IL-8 in the samples were 4.32 ±1.78 pg/mL in the AL > 26 mm group compared to 5.21 ±1.87 pg/mL in the AL < 25 mm group (Table 2). No correlation was found between IL-8 level and the AL (p = 0.235, r = −0.153) (Figure 5).

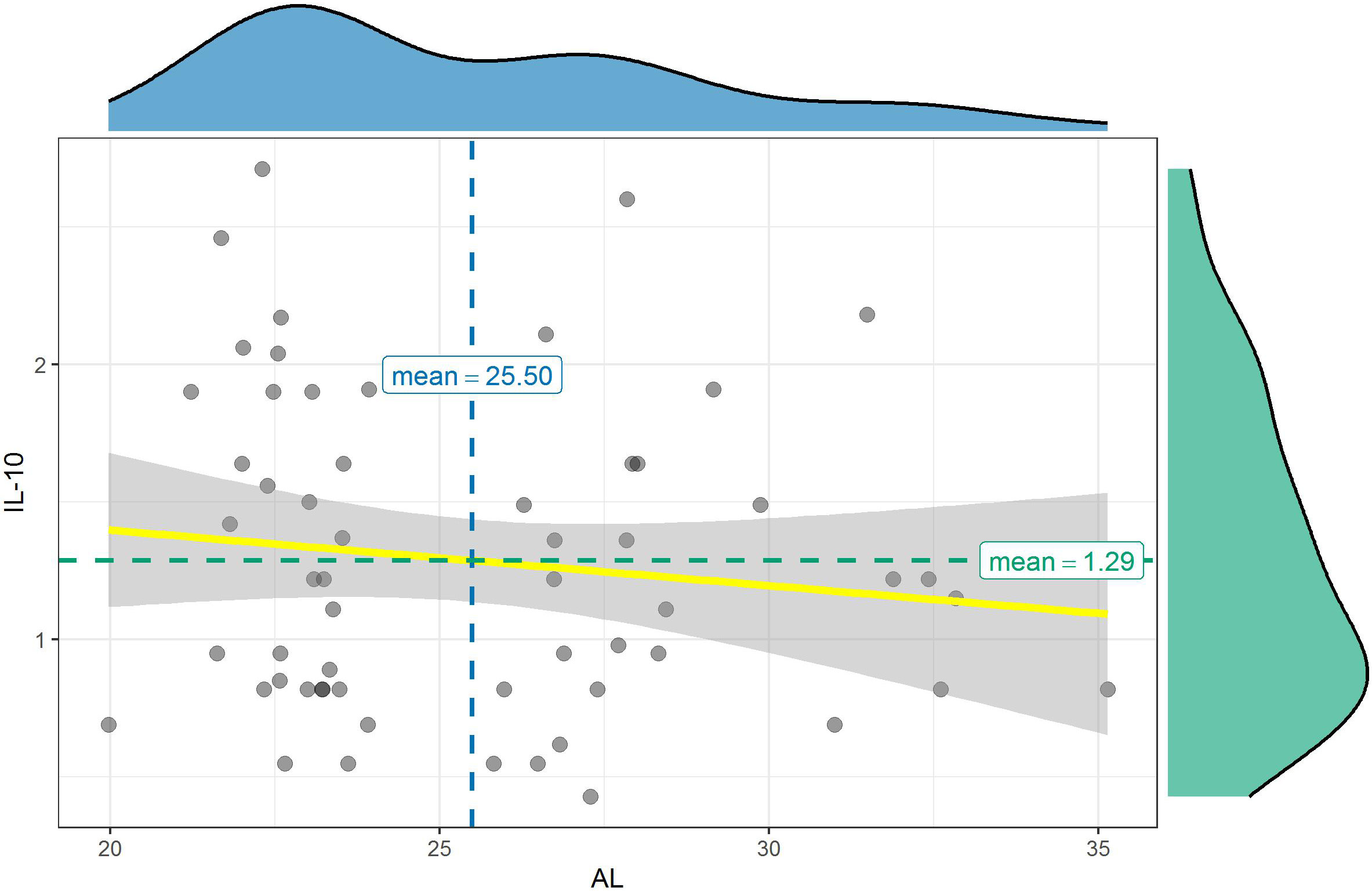

Interleukin 10 levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Student’s t-test revealed that IL-10 level in the aqueous samples of the highly myopic eyes was not significantly different than in the control eyes (p = 0.192). Mean values of IL-10 in the samples were 1.21 ±0.54 pg/mL in the AL > 26 mm group compared to 1.41 ±0.57 pg/mL in the AL < 25 mm group (Table 2). In addition, no correlation was found between IL-10 and the AL (p = 0.351, r = −0.125) (Figure 6).

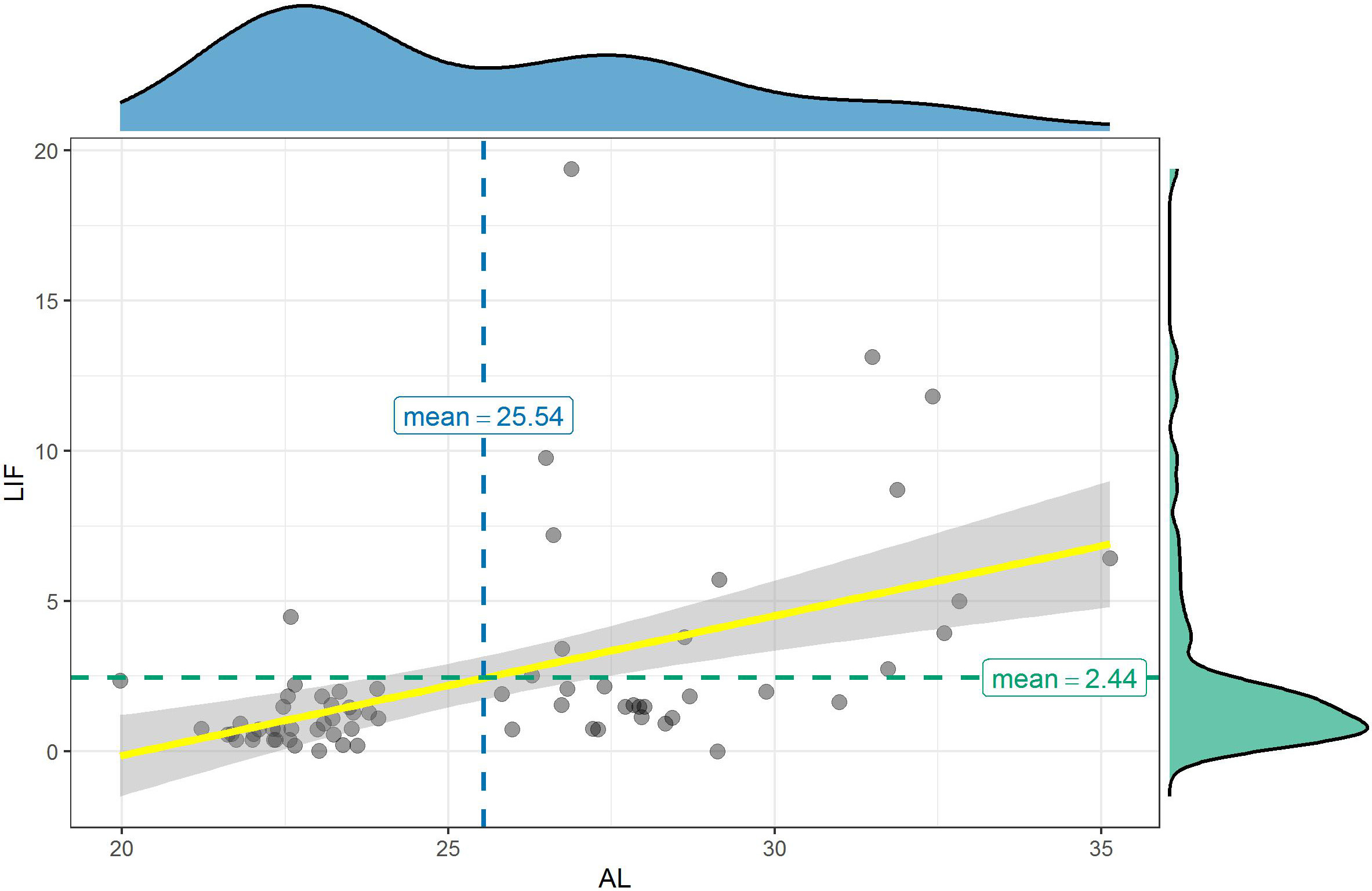

Leukemia inhibitory factor levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Median level of LIF for longer AL group (2.035 pg/mL) was statistically significantly higher than in the shorter AL group (0.750 pg/mL) (U = 210.5, Z = −4.495, p < 0.001; Table 3). There was a correlation between LIF and AL (p < 0.001, r = 0.486) (Figure 7).

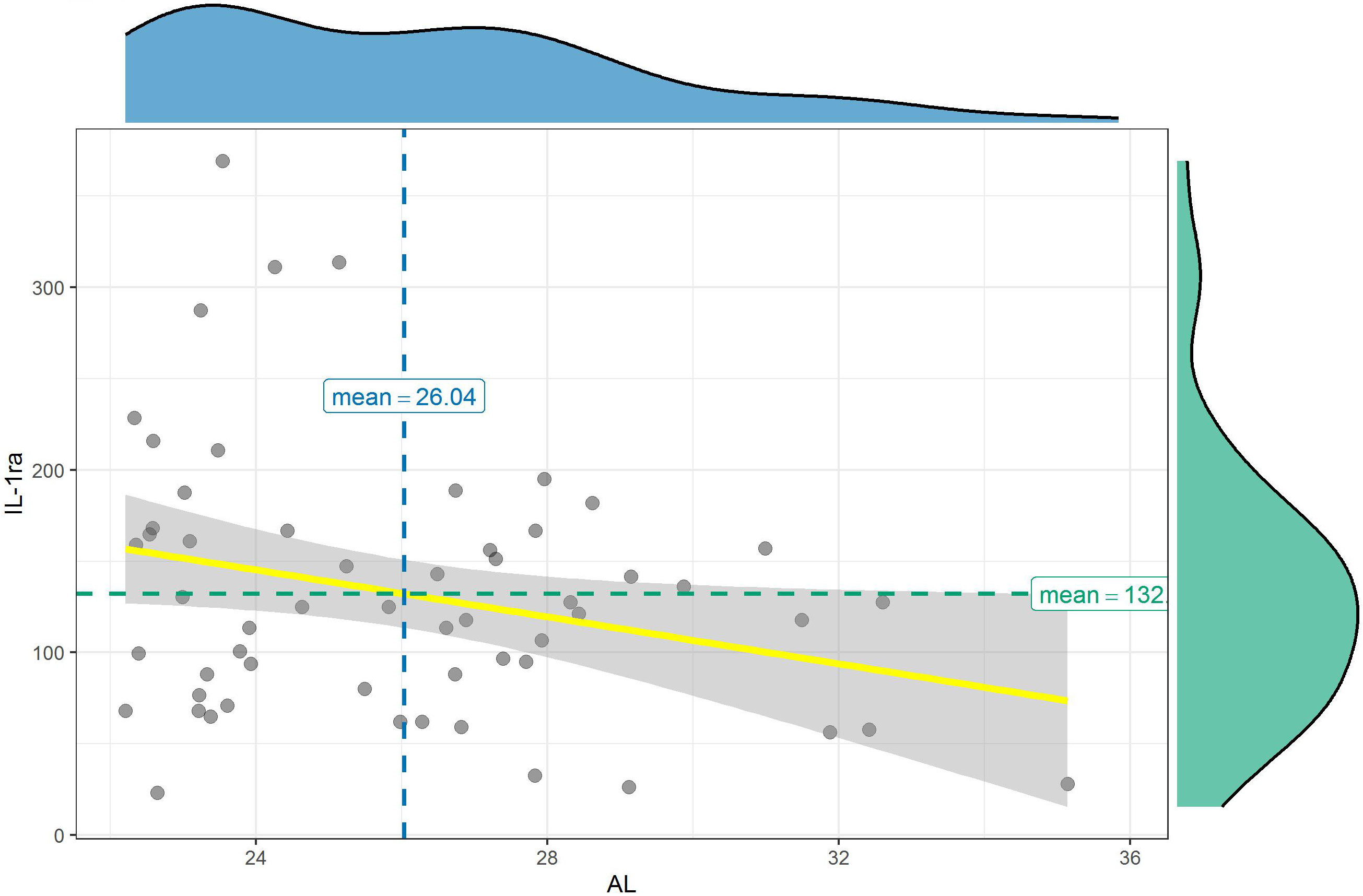

Interleukin 1ra levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Mean values of IL-1ra level were 111.01 ±46.51 pg/mL in the longer AL group compared to 147.22 ±86.60 pg/mL in the shorter AL group. Interleukin 1ra level in the aqueous samples of the longer AL group was significantly lower than in the shorter AL group (p = 0.049). Interleukin 1ra level was negatively correlated with AL (p = 0.038, r = −0.276) (Figure 8).

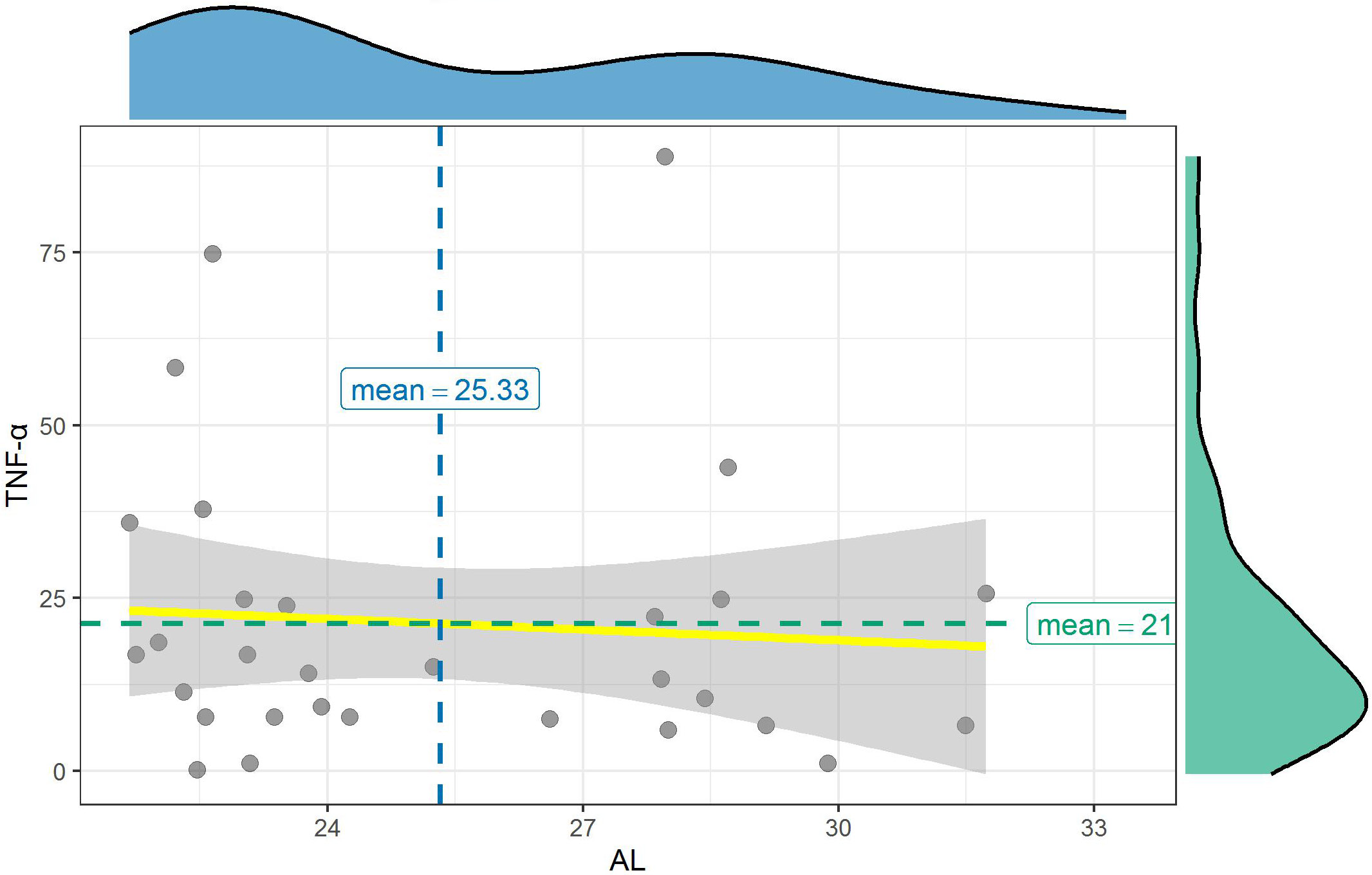

Tumor necrosis factor α levels in the aqueous humor of the study eyes

Tumor necrosis factor α levels could only be detected in 30 samples (n = 30, nAL > 26 group = 13, nAL < 25 group = 17). Its median level for AL > 26 group (13.28 pg/mL) and AL < 25 group (16.86 pg/mL) was not statistically significantly different (U = 99, Z = −0.482, p = 0.650; Table 3). No correlation was found between TNF-α level and the AL (p = 0.687, r = −0.077) (Figure 9).

Discussion

In 2012, Bostrom et al. identified an exercise-induced hormone irisin,6 which is synthesized in several tissues of different species.16 Irisin6 is secreted into the circulation after proteolytic cleavage from its cellular form, FNDC5. Irisin can be found not only in the skeletal muscles, but also in brain regions, such as Purkinje cells, paraventricular nucleus and cerebrospinal fluid.17, 18, 19 A few studies investigated irisin immunoreactivity in the eye of dwarf hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii). In the retina, irisin was found almost in all layers, except outer nuclear layer. Also, irisin immunoreactivity was observed in the cornea.9 Moreover, irisin immunoreactivity was found in the neural retina of the crested porcupine (Hystrix cristata).20 To our knowledge, this is the only study showing that irisin exists in the human aqueous humor.

We are all aware that PA has many benefits, including reducing the risk of developing heart disease, stroke and diabetes. It has been speculated that lifestyle changes such as reduced PA, reduced time spend outdoors and more close-up work might be the driving force behind the rapid increase in myopia.5 Confusion has arisen, because some studies have not distinguished between PA and time spent outdoors. As exercise induces myokine, we decided to analyze irisin in the myopia patients’ eyes compared with the control group.

It is difficult to collect the vitreous fluid of these patients, so we tried the analysis of the aqueous humor and found that irisin level in high myopia group is significantly higher than in the controls. In addition, the positive relationship has been found between irisin level and AL. Given the positive result of our study, irisin may be a new research direction in the future. It is worth considering that if physical exercise is good for myopia, the level of irisin produced in consequence of the exercise should be reduced in the long AL group rather than increased. The ideal time to test if PA and myopia are related to each other would be in childhood. This approach, however, will be difficult due to ethical considerations and harvest method. Our samples are from elder people, which may create a selection bias. Another limitation is the lack of serum level of irisin from the subjects. Further experiments are needed to clarify the detailed mechanisms underlying the relationship between PA, myopia and irisin.

Many researchers believe that close-up work is an independent risk factor for myopia.21, 22, 23, 24 However, unlike the role of lack of outdoor activities, this viewpoint still needs to be proved in the future. As people’s education level improves, reduced time spent outdoors and more close-up work might be the driving force behind the rapid increase in myopia prevalence. The joint effect of the 2 aspects may be one of the reasons for the increasing incidence of myopia. Our research shows that the intraocular irisin level increases with the growth of the AL. Current animal experiments have confirmed that irisin can be produced by smooth muscle cells. In other words, the ciliary muscle may also be the main source of irisin in the eye. Therefore, we speculate that the ciliary muscle, which is an important effector of the ocular accommodation mechanism, increases its activity after long-term close-up work, resulting in increased production of irisin in the eye. Therefore, the ocular level of myokine irisin in patients with axial myopia is significantly increased.

On the other hand, few studies have tested the possible relationship between the chronic inflammation and myopia progression.25, 26, 27 One study assumed that inflammation promotes the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the sclera and results in axial elongation. They found a strong association between AL and IL-6: the longer the AL, the higher IL-6 in the aqueous humor.27 Interleukin 6 is released from the lymphocytes and macrophages, as well as from the skeletal muscle cells, and acts both as a pro-inflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory myokine, depending on the stimuli.28 In our study, there was no significant difference between 2 groups; the same result was achieved in 1 other study with a smaller sample collection.29

Interleukin 6 is related to the increased matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) production, especially in neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory states in human pathophysiology.30 High myopia-related retinal atrophy, either diffuse or patchy, is a type of neurodegenerative change. The location of the retina is an evagination of the brain and also part of the central nervous system (CNS). Recent studies have shown that the thinning of both the retinal nerve fiber layer and choroid, which are the hallmarks of high myopia, were present in AD,31, 32, 33 which is a neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disease. Although we were unable to prove that IL-6 was increased in high myopia patients’ eyes, we found a decreased BDNF level compared to control group. The BDNF is a critical regulator of neural plasticity, is known as a widely distributed neurotrophine and plays an important role in synaptic function and neuronal survival.34 Decreased levels of BDNF have been identified in serum, as well as in hippocampal and cortex samples of AD and PD patients.35, 36, 37 Our result demonstrates the same change in high myopia patients’ aqueous humor, which also shows the possible connection between myopia and neurodegenerative diseases.

Leukemia inhibitory factor is a member of the IL-6 cytokine family. The basic expression of LIF is low; however, it has been confirmed to be upregulated at the inflammation site and the serum is elevated systemically after septic shock.38, 39 Leukemia inhibitory factor is expressed in the CNS; it is also a protective cytokine during inflammatory stress40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and a potential neuroprotective cytokine.45 Studies have reported that LIF plays an important role in the process of retinal degeneration protection via JAK-STAT3 and Akt signaling pathways in animal models of retinal ischemia induced by acute ocular hypertension.46 The result of our study showed that the LIF level in the long AL group was significantly higher than in the control, and LIF was significantly positively correlated with the AL (r = 0.486), indicating that this protective factor was connected with axial myopia progression.

Interleukin 8 is a main chemoattractant for neutrophils. It has been shown that intraocular IL-8 level is higher in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and glaucoma patients.47, 48, 49, 50, 51 Until recently, no study has suggested that IL-8 is related to myopia. We were also unable to find any such association in our samples. Interleukin 10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that reduces activation of T cells. A previous study has also shown that IL-10 promotes ocular neovascularization (NV) through macrophage response to retina ischemia.52 No significant difference of IL-10 level between RP, AMD, glaucoma, and cataract patients has been found by Ten Berge et al.53 The same result has been shown in our study of IL-10 level, which compared high myopia and control group.

Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist is a natural IL-1ra that has a high affinity for IL-1 receptors.54 Studies have shown that IL-1ra can reduce various inflammatory reactions caused by IL-1, such as arthritis55 and graft-versus-host response.56 Previous animal studies have found that after corneal transplantation, IL-1ra inhibits IL-1 in corneal grafts, and a greater dose of IL-1ra is correlated with a lower expression of interleukin 1 receptor I (IL-1RI) and a lighter inflammatory response in corneal grafts.57 Our study confirmed that the IL-1ra level in the aqueous humor of the long AL group was significantly lower than that in the other group. Moreover, the longer the AL, the lower the IL-1ra level. Based on the negative correlation, we assumed that higher IL-1ra in the control group suppresses a part of the inflammatory response, and therefore slows the progression of axial myopia. Our result is consistent with previous studies and further confirmed the correlation between myopia and inflammation.

Increased TNF-α levels have been reported in glaucoma patients’ intraocular fluid, the trabecular meshwork, optic head, and the retina58, 59; however, we could not detect TNF-α in most of our samples. As a result, we were unable compare the level in our groups. Cytokines act at concentrations from 10–10 mol/L to 10–15 mol/L to stimulate target cell functions, and such a low concentration range aggravates the detection problems, for instance, causing insufficient assay sensitivity. Different laboratory techniques and diverse patients may be a reason.

Limitations

Our samples are from elder people, which may create a selection bias. Another limitation is the lack of serum level of irisin from the subjects. Further experiments are needed to clarify the detailed mechanisms underlying the relationship between PA, myopia and irisin.

Conclusions

Irisin levels in the aqueous humor are elevated in high myopia patients, which opens a new direction to discover the relationship between PA and myopia. We also found BDNF decreased in high myopia patients’ eye, which demonstrated the connection between myopia and neurodegenerative diseases, for instance, AD. The mechanisms of how they influence the myopia progression still need to be clarified.