Abstract

Background. Induction of acquired drug resistance occurs frequently with cisplatin-based therapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). As recent studies have demonstrated that deregulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) is associated with drug resistance in cancers, correcting the deregulation of miRNAs represents a promising strategy to reverse acquired resistance in NSCLC.

Objectives. This study investigated the functional role of miR-15b in cisplatin resistance in NSCLC.

Materials and methods. Cisplatin-resistant PC9 and A549 NSCLC cell lines (PC9-R and A549-R) were established through long-term exposure to cisplatin. Differences in miR-15b expression between cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cell lines and their parental cell lines were identified through quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The effect of anti-miR-15b on the sensitivity of PC9-R and A549-R to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity was evaluated using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays. Regulation of GSK-3β by miR-15b was confirmed with luciferase reporter assays. Cell apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were measured using flow cytometry analysis.

Results. In PC9-R and A549-R cells, miR-15b was significantly overexpressed. However, knockdown of miR-15b clearly reduced cisplatin resistance in PC9-R and A549-R cells. Researching the mechanism, we proved that GSK-3β was the target of miR-15b. Knockdown of miR-15b significantly increased the expression GSK-3β and thus promoted the degradation of MCL-1, which is a key anti-apoptosis protein. As a result, anti-miR-15b expanded the cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells.

Conclusions. Knockdown of miR-15b partially reversed cisplatin resistance in NSCLC cells through the GSK-3β/MCL-1 pathway.

Key words: NSCLC, cisplatin, GSK-3β, miR-15b, MCL-1

Background

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of malignant tumor in the world. Despite current developments in medical technology, including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, no substantial change in survival has been seen, and NSCLC is still a leading cause of cancer-related deaths.1, 2 Therefore, NSCLC is a serious threat to human life. Today, chemotherapy is still an irreplaceable and valuable treatment for NSCLC patients without epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation.3, 4 However, repeated chemotherapy usually reduces the sensitivity of cancer cells to the antineoplastic drugs.5, 6, 7 Thus, drug resistance is a serious cause of poor prognoses in cancer patients, especially for NSCLC patients.8, 9 Overcoming the chemoresistance of NSCLC is an urgent need in current cancer therapy.

Today, cisplatin is still a frequently used platinum-based chemotherapeutic drug. Furthermore, cisplatin is still used as the first-line chemotherapeutic drug for patients with advanced NSCLC.10 However, clinical application of cisplatin is limited by harsh side effects including nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, neurotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and digestive reaction.11 Given this, combined treatment with sensitizing agents is desirable to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to cisplatin.

As a broad-spectrum and cell cycle non-specific drug, cisplatin cross-links with DNAs to inhibit DNA replication and transcription. As a result, the initiated apoptotic process is accompanied by alterations of the outer mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and permeability. Finally, mitochondrial apoptosis occurs.12, 13 However, NSCLC cells usually acquired drug resistance to resist apoptotic pathways when they were under long-term cisplatin stress under the effect of cisplatin.14, 15 We aimed to explore the potential mechanisms and to reduce the cisplatin resistance of NSCLC.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of short non-coding RNAs whose length is approx. 18–25 nucleotides.16, 17 They function as gene regulators via targeting mRNAs.18, 19 Since approx. 60% of all human genes are targeted by miRNAs, the miRNAs participate in various biological processes in cells.20, 21 Deregulation of miRNAs has been acknowledged to be responsible for tumorigenesis, cancer development and survival.22, 23 MiR-15b has been reported to function as an important member of cancer-related miRNAs. Studies indicate that miR-15b is frequently overexpressed in some cancers, including NSCLC.24 Furthermore, previous research found that overexpression of miR-15b was associated with drug resistance in cancer.25 Despite miR-15b having been shown to promote proliferation and invasion of NSCLC,26 the role of miR-15b in chemoresistance in NSCLC is still unclear.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to investigate the functional role of miR-15b in cisplatin resistance in NSCLC. To achieve this, cisplatin-resistant NSCLC models were created to explore the potential role of miR-15b in cisplatin resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

PC9 and A549, which are human NSCLC cell lines, were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 5% CO2, 37°C incubator. To establish the cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cell models (PC9-R and A549-R), PC9 and A549 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of cisplatin. In short, PC9 and A549 cell lines were initially treated with 0.5 µM cisplatin for 2 months. Then, the cisplatin concentration was increased by 0.1 µM every 2 weeks until the final concentration was 2 µM.

qRT-PCR

Relative expression of miR-15b, GSK-3β and MCL-1 was detected using quantitative reverse transcriptase real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. In short, Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) was used to isolate the total RNAs of the cell lines. In order to detect miR-15b, cDNAs were synthesized with One Step PrimeScript miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan). In order to detect GSK-3β and MCL-1, cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Then, the relative expression of miR-15b, GSK-3β and MCL-1 was detected using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Primers were obtained from Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) and had the following sequences: miR-15b, 5’-TAGCAGCACATCATGGTTTACA-3’; MCL-1 forward, 5’-TCGGACTCAACCTCTACTG-3’ and reverse, 5’-GGCTTCCATCTCCTCAA-3’; GSK-3β forward, 5’-ACGCTCCCTGTGATTTAT-3’ and reverse, 5’-CTCTGATTTGCTCCCTTG-3’. The PCR was performed under the following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s, and 1 cycle of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s and 95°C for 15 s for dissociation. The fold change of miR-15b was normalized to U6 snRNA and the fold change of GSK-3β and MCL-1 was normalized to GAPDH with the comparative cycle threshold method (2−ΔΔCT).

Transfection

To knockdown the GSK-3β and MCL-1 directly, GSK-3β

and MCL-1 siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA). To overexpress the GSK-3β and MCL-1 directly, the open reading frame of GSK-3β and MCL-1 without the 3’-UTR was amplified and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Life Technologies), respectively. miR-15b mimics (5’-UAGCAGCACAUCAUGGUUUACA-3’), anti-miR-15b (5’-UGUAAACCAUGAUGUGCUGCUA-3’) and negative control oligonucleotide (NCO, 5’-UGCACAGUUUAACCAGGAUUCA-3’) were purchased from Genepharma Company (Shanghai, China). For transfection, plasmid (2 μg/mL) and RNA oligonucleotides (50 pmol/mL) were transfected into the NSCLC cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were collected and used for the following experiments 24 h after transfection.

Cell viability assay

5 × 103 transfected cells were seeded on 96-well plates. Then, different concentrations of cisplatin were used to treat these cells for 48 h. Subsequently, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; 10 µL; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The absorbance in each well was measured at 450 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated as follows: cell viability rate = optical density (OD) value in drug administration group/OD value in control group. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of cisplatin in the NSCLC cell lines was calculated according to the cell viability curves. Cell viability assays were repeated 3 times to calculate the IC50.

Luciferase reporter assay

According to the manufacturer’s instruction, the GSK-3β 3’ UTR containing the seed region of the miR-15b binding site (UGCUGCUU) was cloned into the pGL3 luciferase reporter vector (Promega, Madison, USA). The recombined luciferase reporter vector was named as pGL3-wt GSK-3β. The mutant plasmid, pGL3-mt GSK-3β, was created through mutating the seed region of the miR-15b binding site (UGCUGCUU to UGCACCUU) using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (TaKaRa). For luciferase reporter analysis, cells were co-transfected with the pGL3-wt GSK-3β (or pGL3-mt GSK-3β), Renilla luciferase pRL-TK vectors (Promega) and the miR-15b mimics (or anti-miR-15b) using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h incubation, luciferase activities were measured by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega). Relative firefly luciferase activities were determined through normalization to Renilla luciferase activities in each well.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis

Treated cells were harvested and washed with PBS. For MMP analysis, cells were stained with JC-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA) followed by detection with flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA). Cells that emitted red fluorescence were indicative of high mitochondrial membrane potential. To detect the apoptosis rate, the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Sigma–Aldrich) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. It is generally believed that Annexin V positive cells are the total number of apoptotic cells.

Statistical analyses

The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and obtained from 3 independent experiments. SPSS v. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) software was used for statistical analyses. Two-tailed t-tests were used to estimate the statistical difference between 2 groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to determine differences between three or more groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

Overexpression of miR-15b

in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells

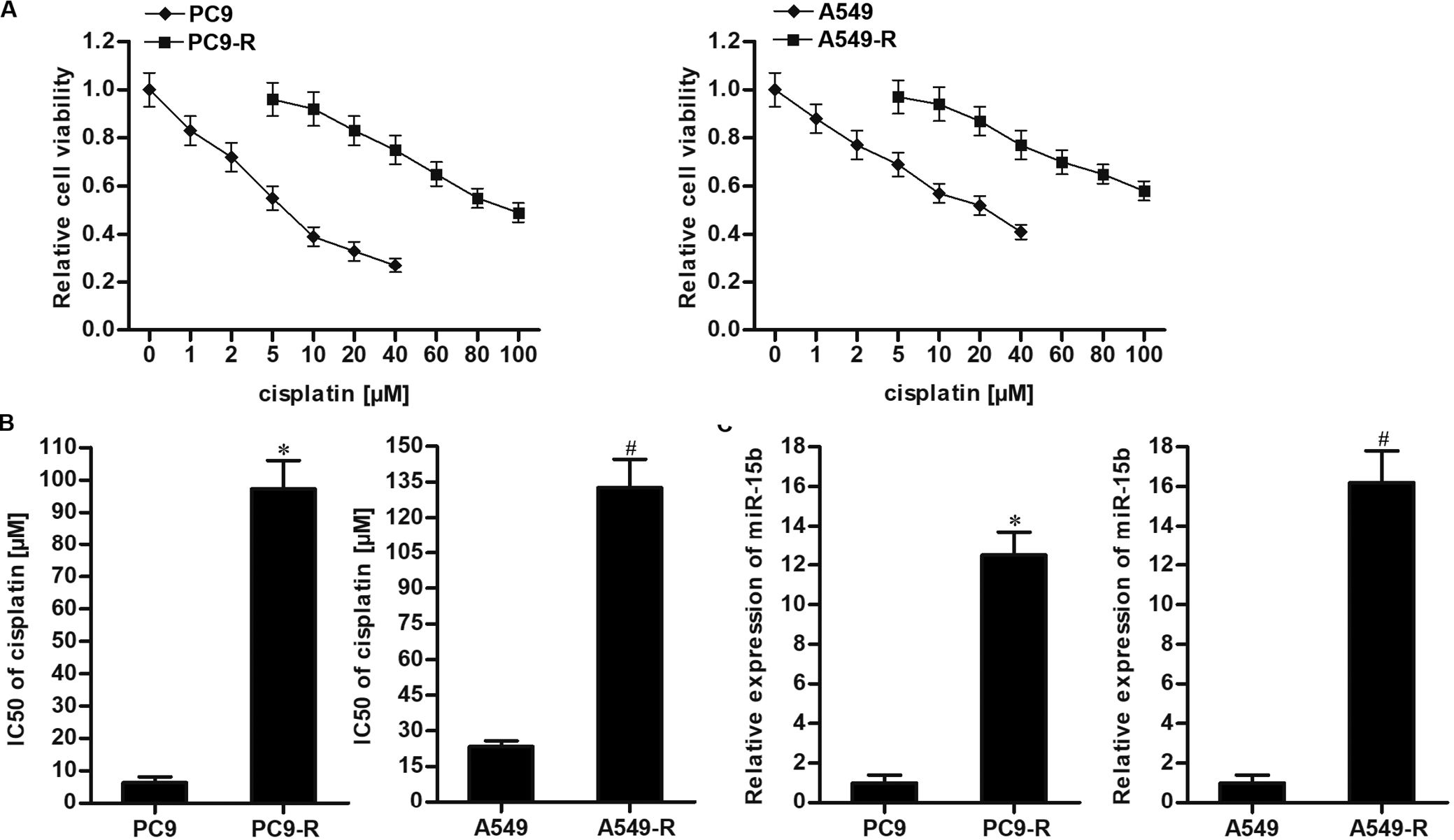

We first evaluated the cisplatin resistance of PC9-R and A549-R cells. As shown in Figure 1A, the cytotoxicity of cisplatin was slighter in PC9-R and A549-R cell lines compared to the PC9 and A549 cells. After analysis of the cell viability curves, we confirmed that the IC50 of cisplatin for PC9-R and A549-R was significantly higher than their parental cell lines PC9 and A549, respectively (Figure 1B). After analysis of miR-15b, we found that miR-15b in PC9-R and A549-R cells was clearly overexpressed compared to the PC9 and A549 cells, respectively (Figure 1C). These results suggested the potential role of miR-15b in determining the cisplatin resistance of NSCLC.

Knockdown of miR-15b reduced the cisplatin resistance in NSCLC cells

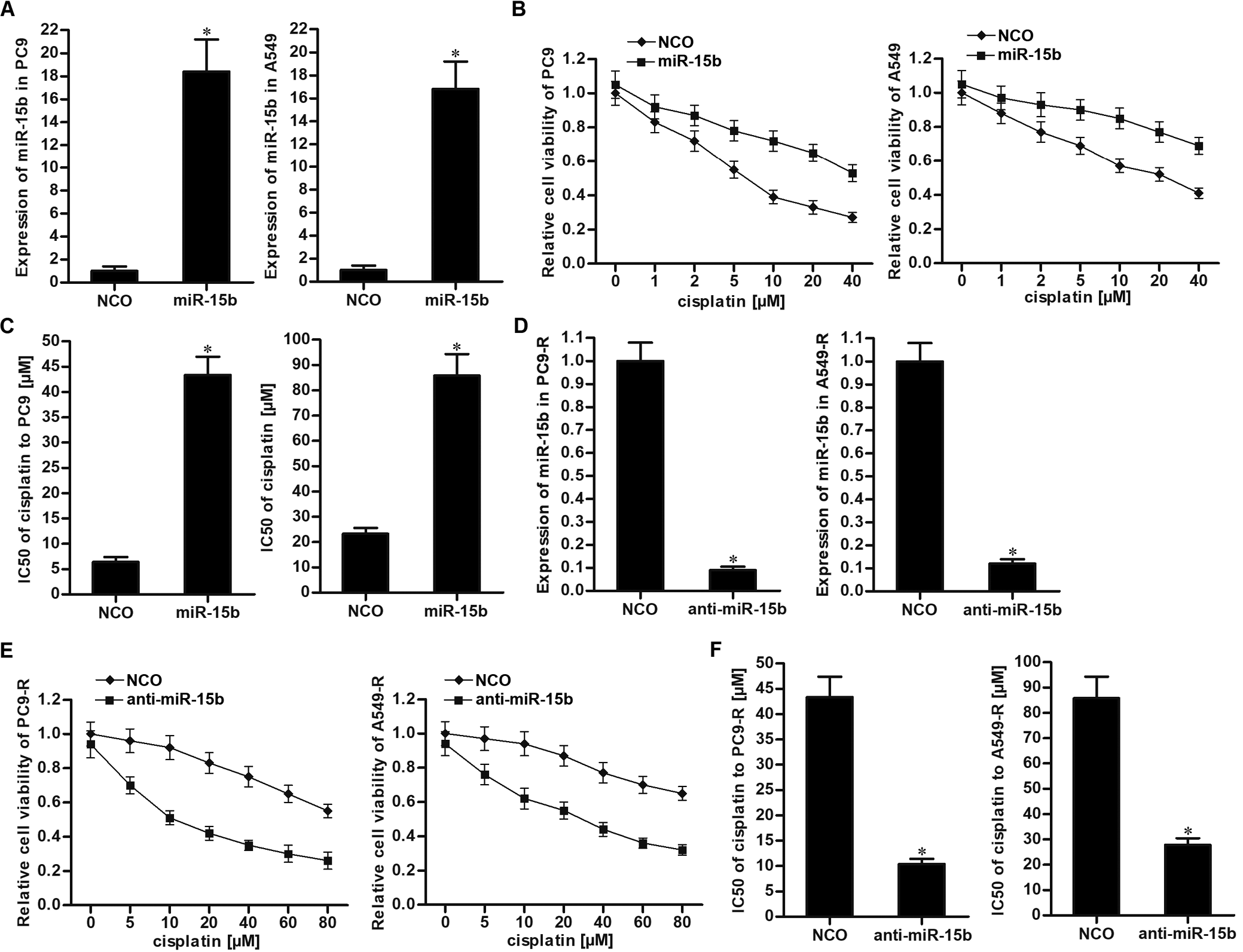

To investigate the role of miR-15b in the cisplatin resistance in NSCLC, we overexpressed the miR-15b directly in PC9 and A549 cells by transfecting the miR-15b mimics (Figure 2A). Results of the cell viability assay showed that overexpression of miR-15b enhanced the resistance of PC9 and A549 cells to different concentrations of cisplatin (Figure 2B). After analysis of the cell viability curves, we confirmed that miR-15b increased the IC50 of cisplatin for PC9 and A549 cells (Figure 2C). On the other hand, we knocked down miR-15b directly in PC9-R and A549-R cells through transfection with anti-miR-15b (Figure 2D). We found that anti-miR-15b treatment increased the sensitivity of PC9-R and A549-R cells to different concentrations of cisplatin (Figure 2E). After analysis of the cell viability curves, we confirmed that anti-miR-15b significantly decreased the IC50 of cisplatin for PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 2F). Our data indicated that miR-15b partially determined the sensitivity of NSCLC cells to cisplatin. Furthermore, we demonstrated that knockdown of miR-15b can partially reverse cisplatin resistance in NSCLC.

MiR-15b targets GSK-3β in NSCLC

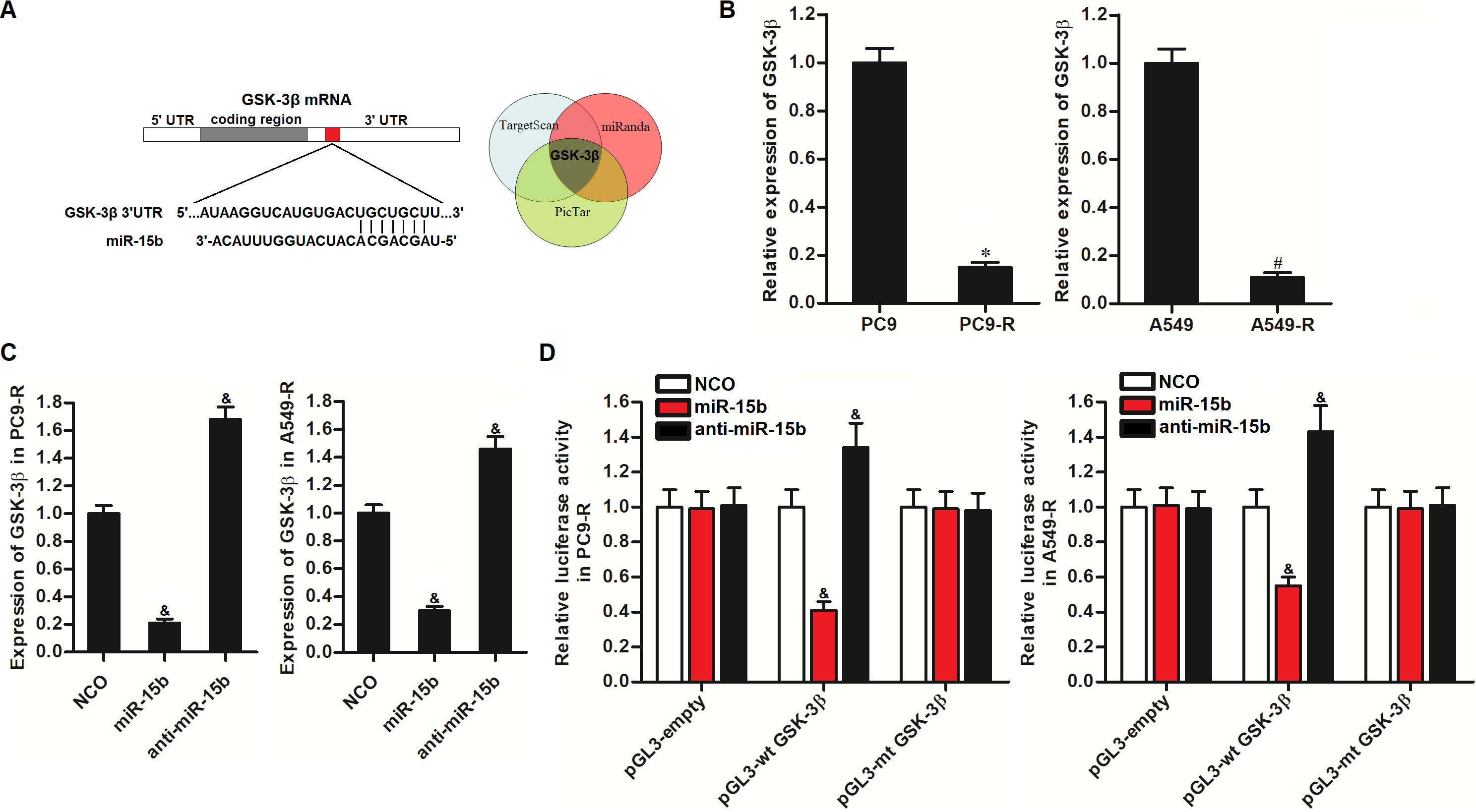

To explore how anti-miR-15b reduced the cisplatin resistance, miRanda (http://www.mirbase.org/), TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) and PicTar (https://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/cgi-bin/PicTar_vertebrate.cgi) databases were used to search for potential mRNA targets. The results showed that GSK-3β contained a putative binding site for miR-15b and was commonly predicted by all of these databases (Figure 3A). Furthermore, in contrast to the overexpression of miR-15b in PC9-R and A549-R, we found that the expression level of GSK-3β in PC9-R and A549-R cells was significantly lower than their parental PC9 and A549 cells (Figure 3B). We therefore predicted that miR-15b targets GSK-3β in NSCLC. Subsequently, we altered the expression of miR-15b in PC9-R and A549-R cells using the miR-15b mimics and anti-miR-15b before detection of GSK-3β expression. We showed that miR-15b decreased the protein levels of GSK-3β, whereas anti-miR-15b increased the expression of GSK-3β (Figure 3C). Furthermore, results of luciferase reporter assays showed that miR-15b significantly decreased the luciferase activities of pGL3-wt GSK-3β reporters, whereas anti-miR-15b clearly increased the luciferase activities of pGL3-wt GSK-3β reporters (Figure 3D). Taken together, we confirmed that the expression of GSK-3β was regulated by miR-15b in PC9-R and A549-R cells.

Expression level of GSK-3β partially determines cisplatin resistance in NSCLC

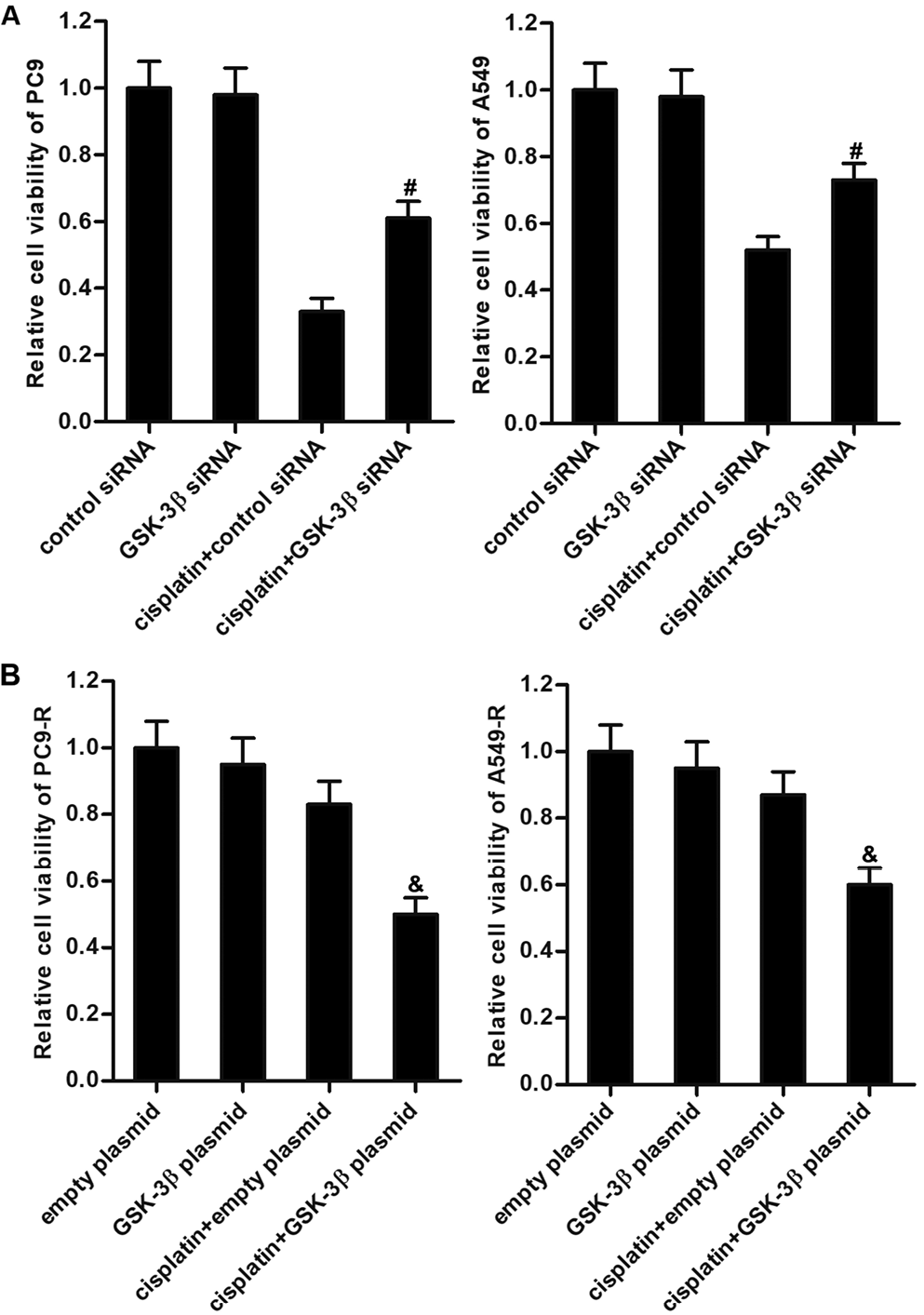

To investigate the role of GSK-3β in cisplatin resistance in NSCLC, we performed gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments using GSK-3β in NSCLC cells. We then found that GSK-3β siRNA treatment significantly reduced the cytotoxicity of cisplatin in PC9 and A549 cells (Figure 4A). On the other hand, we found that GSK-3β plasmid treatment clearly reduced cisplatin resistance in PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 4B). These data indicated that reduction of GSK-3β was partially responsible for cisplatin resistance in PC9-R and A549-R cells.

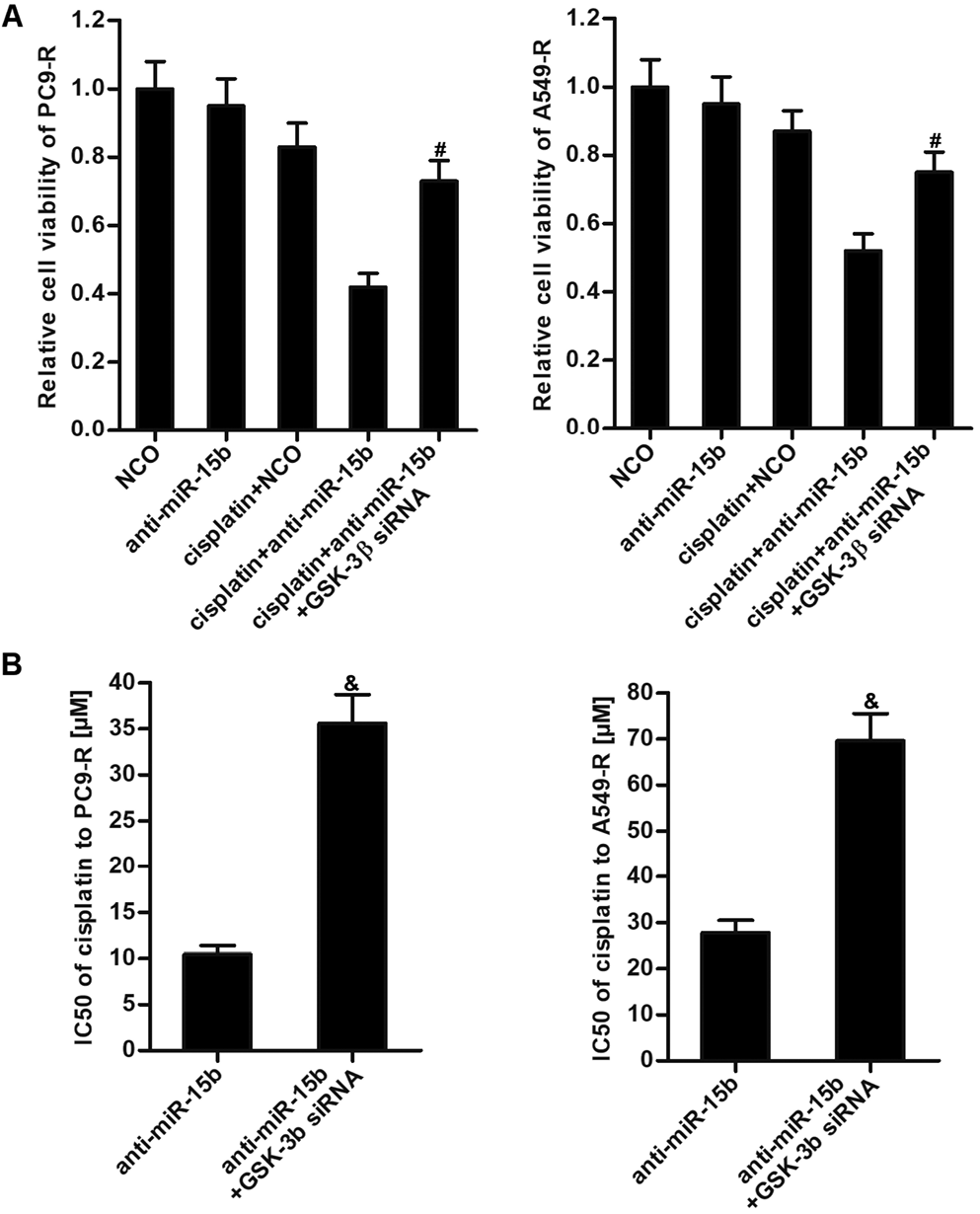

Anti-miR-15b reduces cisplatin resistance in NSCLC by increasing GSK-3β expression

As anti-miR-15b significantly enhanced the effect of cisplatin in PC9-R and A549-R cells, we next investigated the role of GSK-3β in them. We found that cells treated with GSK-3β siRNA were resistant to the combination treatment with cisplatin and anti-miR-15b (Figure 5A). We then confirmed that GSK-3β siRNA attenuated anti-miR-15b’s reduction of the IC50 values for cisplatin in PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 5B). Our data illustrate that anti-miR-15b partially reversed cisplatin resistance in NSCLC by increasing GSK-3β expression.

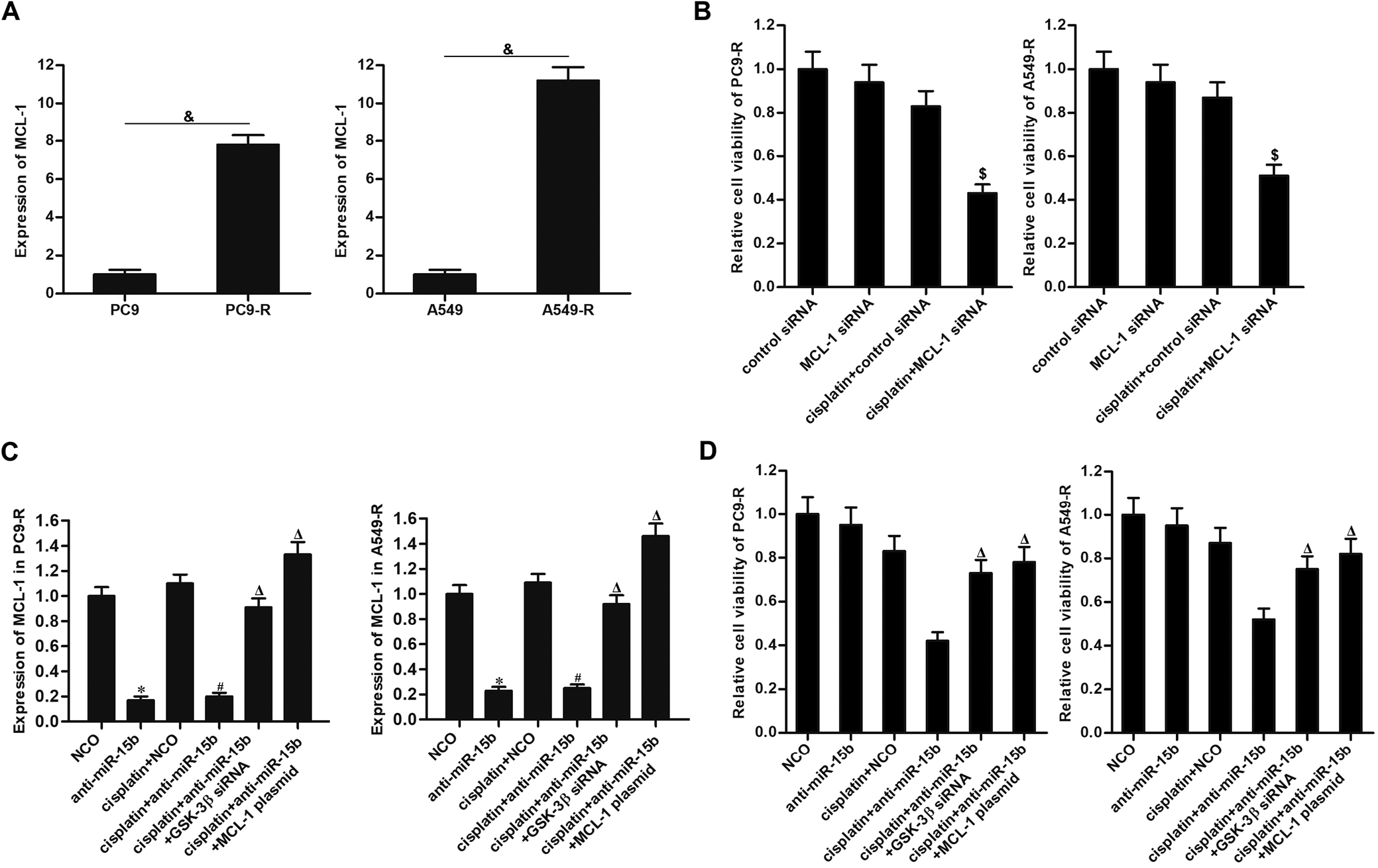

Anti-miR-15b inhibited the expression of MCL-1 by increasing GSK-3β expression

Previous research has indicated that GSK-3β induces degradation of MCL-1, which is a key anti-apoptotic protein.27 In this study, we observed that MCL-1 was overexpressed in PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 6A). Next, we found that direct knockdown of MCL-1 significantly enhanced the effect of cisplatin in PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 6B). These data indicated that overexpression of MCL-1 was partially responsible for cisplatin resistance in NSCLC. On the other hand, we confirmed that anti-miR-15b inhibited the expression MCL-1, whereas knockdown of GSK-3β increased the MCL-1 level in PC9-R and A549-R cells that were co-treated with cisplatin and anti-miR-15b (Figure 6C). We thus confirmed that anti-miR-15b inhibited the expression of MCL-1 through the GSK-3β pathway. Furthermore, we found that enforced expression of MCL-1 using the MCL-1 plasmid protected the PC9-R and A549-R cells from the cytotoxicity induced by combination treatment with cisplatin and anti-miR-15b (Figure 6D). These data illustrate that anti-miR-15b partially reduced cisplatin resistance in PC9-R and A549-R cells through the GSK-3β/MCL-1 pathway.

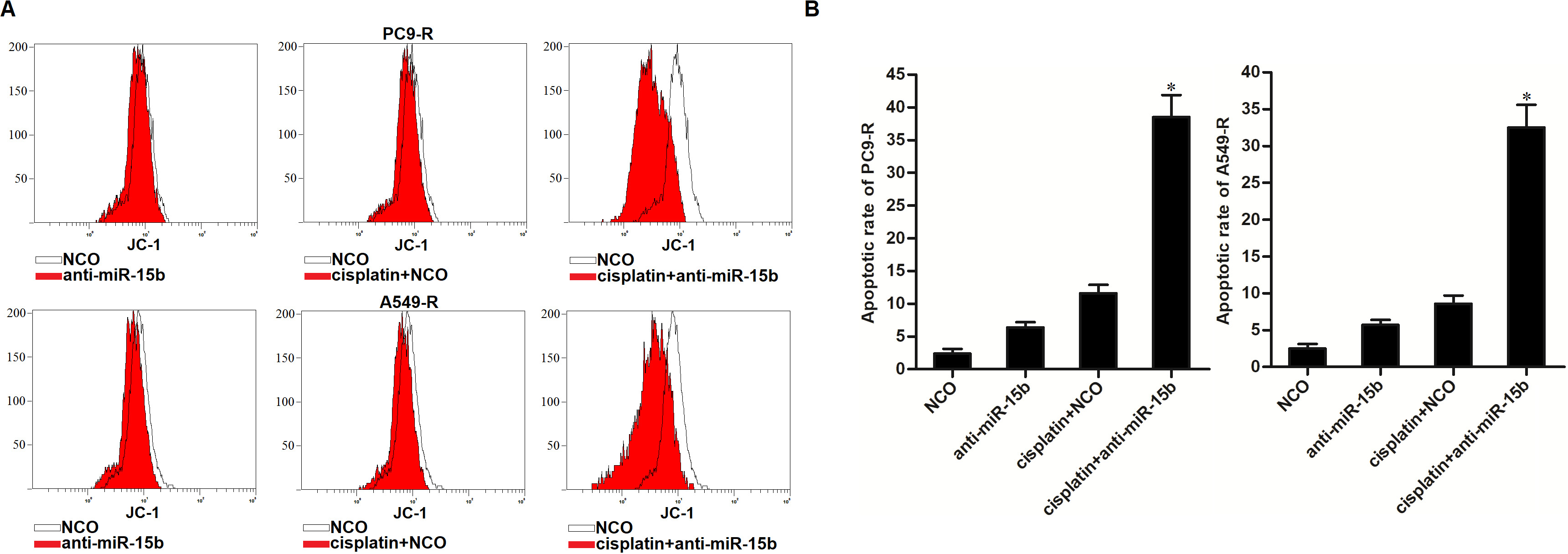

Anti-miR-15b enhanced

the cisplatin-induced apoptosis of PC9-R and A549-R cells through the mitochondrial pathway

Our earlier results indicated that anti-miR-15b reduced cisplatin resistance in NSCLC. We next explored the role of anti-miR-15b in the cisplatin-induced apoptosis pathway. We showed that anti-miR-15b enhanced the effect of cisplatin in inducing the mitochondria collapse in PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 7A). Accompanied by a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), the combination of cisplatin and anti-miR-15b induced significant apoptosis of PC9-R and A549-R cells (Figure 7B). Taken together, we demonstrated that anti-miR-15b enhanced the cisplatin-induced apoptosis of PC9-R and A549-R cells through the mitochondrial pathway.

Discussion

In this study, we continuously exposed NSCLC cell lines to cisplatin. As a result, these cells acquired resistance against cisplatin. Exploration of potential mechanisms and the use of novel approaches is needed to overcome cisplatin resistance in NSCLC. Recently, studies have indicated that chemoresistance in cancer is associated with deregulation of miRNAs. Correcting miRNA expression has been found to antagonize drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma,28 prostate cancer29 and breast cancer.30 In NSCLC, studies have also revealed functions for miRNAs. For instance, miR-100 and miR-873 can confer resistance to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC cells.31, 32 MiRNAs have been recognized as a promising target for NSCLC treatment. MiR-15b was reported to function as a tumor promoter in some cancers including NSCLC.24, 25, 26 However, the potential role of miR-15b in cisplatin resistance in NSCLC is still unclear. In the present study, we showed a significant overexpression of miR-15b in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells compared to their parental cells. Interestingly, we found that increased miR-15b expression can partially induce cisplatin resistance in routine NSCLC cell lines, whereas knockdown of miR-15b expression can reduce cisplatin resistance in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cell lines. Our work confirmed that miR-15b partially determined the cisplatin sensitivity of NSCLC cells. MiR-15b may be a potential therapeutic target for improving the cisplatin-based chemotherapy in NSCLC.

GSK-3β is a serine/threonine protein kinase. Previous studies have indicated that inhibition of GSK-3β is responsible for occurrence, progression, metastasis, and drug resistance of multiple cancers such as colon cancer,33 hepatocellular carcinoma34 and breast cancer.35 Therefore, GSK-3β functions as a tumor suppressor.

Drug resistance is a significant challenge to overcome. The mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer cells include at least one of the following: enhancement of DNA damage repair, enhancement of drug inactivation, dysregulation of growth factor signaling pathways, and/or dysregulation of survival-related genes.36 Recent studies have indicated that GSK-3β induces degradation of MCL-1.27, 37 Therefore, deficiency of GSK-3β means overexpression of MCL-1. MCL-1 is a key anti-apoptotic protein belonging to the Bcl-2 family.38 As MCL-1 is mainly located on the mitochondrial membrane, MCL-1 prevents the mitochondrial apoptosis of cancer cells by inactivating pro-apoptotic proteins such as Noxa and Puma. Overexpression of MCL-1 has been shown to be an important mechanism for the development of chemoresistance in cancer cells.39, 40

In this study, a significant reduction of GSK-3β expression and an increase in MCL-1 expression was observed in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells compared to standard NSCLC cells. Furthermore, we confirmed that the downregulation of GSK-3β and overexpression of MCL-1 was responsible for cisplatin resistance in NSCLC. These data illustrated that the cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells developed drug resistance through dysregulation of survival-related genes.

In summary, to obtain the drug resistance, the cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells overexpressed miR-15b, reducing the expression level of GSK-3β. As a result, MCL-1 accumulated and the NSCLC cells gained resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. According to the pathway, anti-miR-15b (miR-15b antisense oligonucleotides) was used to correct the overexpression of miR-15b in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells. As a result, expression of GSK-3β was increased and MCL-1 was degraded. Moreover, anti-miR-15b expanded mitochondrial apoptosis of NSCLC cells, which were under the stress of cisplatin. Taken together, this study provides the basis for potential intervention using miRNAs in cancer therapy.

Limitations

Although we have proved that knockdown of miR-15b reduces cisplatin resistance in NSCLC cell lines, the role of miR-15b in NSCLC patients is still unclear. Therefore, further study is required to clarify the effect of miR-15b on chemotherapy in vivo.

Conclusions

Our findings provide evidence that anti-miR-15b partially reversed cisplatin resistance in NSCLC through the GSK-3β/MCL-1 pathway. However, further studies are required to evaluate the approach of anti-miR-15b adjuvant treatment in clinical applications.