Abstract

Skeletal dysplasias are a heterogeneous group of congenital bone and cartilage disorders with a genetic etiology. The current classification of skeletal dysplasias distinguishes 461 diseases in 42 groups. The incidence of all skeletal dysplasias is more than 1 in every 5000 newborns. The type of dysplasia and associated abnormalities affect the lethality, survival and long-term prognosis of skeletal dysplasias. It is crucial to distinguish skeletal dysplasias and correctly diagnose the disease to establish the prognosis and achieve better management. It is possible to use prenatal ultrasonography to observe predictors of lethality, such as a bell-shaped thorax, short ribs, severe femoral shortening, and decreased lung volume. Individual lethal or life-limiting dysplasias may have more or less specific features on prenatal ultrasound. The prenatal features of the most common skeletal dysplasias, such as thanatophoric dysplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta type II, achondrogenesis, and campomelic dysplasia, are discussed in this article. Less frequent dysplasias, such as asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, fibrochondrogenesis, atelosteogenesis, and homozygous achondroplasia, are also discussed.

Key words: prenatal diagnostic, skeletal dysplasia, lethal, life-limiting

Background

Skeletal dysplasias (SD, also known as osteochondrodysplasias) are an etiologically heterogeneous group of clinical skeletal disorders that disturb the growth and development of bones and cartilage. There are 461 different diseases belonging to SD, which are classified into 42 groups (Nosology and Classification of Genetic Skeletal Disorders 2019) according to their clinical/pathological, biochemical, imaging, and molecular characteristics.1

In most cases, SD is the result of mutations in single genes. Less often, dysplasias result from chromosomal anomalies, environmental teratogenic agents or multifactorial inheritance.2, 3, 4 The average incidence of all types of SD is more than 1 in every 5000 newborns.5, 6, 7 The real incidence rate may be higher because SD includes both viable as well as life-limiting and lethal disorders.2, 3 It is suggested that SD of the fetus has an incidence rate of about 5 in every 1000 pregnancies.8

Objectives

The aim of the present review is to better understand the natural history and the course of lethal and life-limiting SD, as well as its molecular etiology. Such understanding will support the management and development of therapeutic possibilities for these conditions.

Methods of literature search

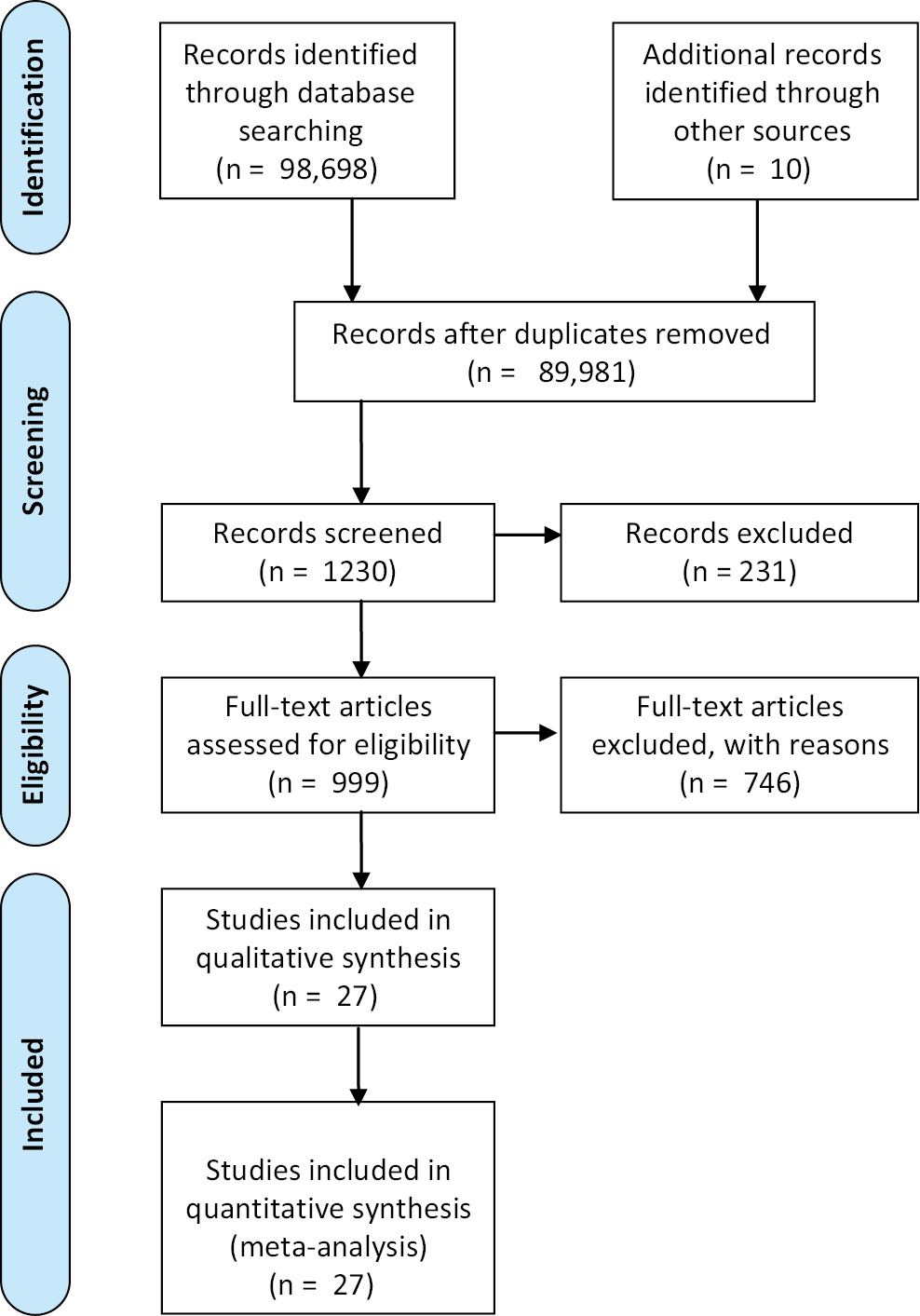

PubMed was used to search the literature. First, the keywords “life-limiting prognosis AND skeletal dysplasia OR prenatal diagnosis” were used, followed by the single term “lethal skeletal dysplasia”, to identify all articles describing poor prognosis of SD diagnosed prenatally. A publication year filter was applied to restrict the results to 1993–2020. If the abstract mentioned syndromes with SD with poor prognosis diagnosed prenatally, the full article text was then analyzed (Figure 1).

Results and discussion

Symptoms of skeletal dysplasia

A characteristic feature of SD is body disproportion due to shortening of the limbs, the trunk, or both.4, 5, 6, 9 If the limbs are short (short-limb dwarfism), the linear growth deficiency can involve the proximal segment (humerus/femur), intermediate segment (radius and ulna/tibia and fibula), distal segment (hands/feet), or all segments of the limbs, with the appropriate terms being, respectively, rhizomelic, mesomelic, acromelic shortening, or micromelia. Short-trunked dwarfism is mainly caused by changes in the spine (e.g., vertebral fusion, dysplastic changes, platyspondyly, kyphoscoliosis) or/and chest (e.g., small chest, barrel-shaped chest).6, 10, 11 Some dysplasias are characterized by deformity, such as bowing of long bones (campomelia) or talipes, asymmetry of limb length, and preaxial (radial/thumb or tibial side) or postaxial (ulnar/little finger or fibular) polydactyly, as well as a high incidence of recurrent fractures.12 Other features of SD may include facial dysmorphia (e.g., micrognathia, frontal bossing, depressed nasal bridge, midface hypoplasia) and a variety of extra-skeletal manifestations, such as neurological, auditory, visual, pulmonary, cardiac, renal, and psychological symptoms.3, 11

Therefore, to establish a precise diagnosis of a particular SD, it is important to describe what segment of long bones and what parts of the body are affected. Specifically, it is important to describe which segment of long bones and which part of the body is affected and to evaluate the affected spine and thorax, hands/feet, calvarium, and the face (frontal bossing, presence of nasal bone, micrognathia), and to assess the involvement of other organs.6, 12, 13 During prenatal evaluation, it is important to assess the volume of amniotic fluid and the presence of fetal hydrops.12, 13

The type of dysplasia and associated abnormalities affect the lethality, survival and long-term prognosis of SD. Early parental diagnosis of SD may improve adequate counseling, pre-delivery planning, pregnancy, and postnatal management.12

Lethal or life-limiting dysplasias

A particular group of SD is lethal or life-limiting. It is suggested that 75–80% of prenatally detected SD is lethal.8, 14, 15 Lethality is defined as inevitably causing or capable of causing death in the prenatal period or shortly after birth. According to Krakow, defining lethality in the prenatal period can be accomplished by 2 means: 1) a certain molecular diagnosis of a known lethal dysplasia; or 2) precise clinical assessment or ultrasound showing the presence of changes correlating with lethality.4 The prediction of lethality is based on specific features, namely, the presence of a bell-shaped thorax, short ribs, severe femoral shortening (>4 standard deviations), lung volume <5th percentile of expected for gestational age, femur length to abdominal circumference ratio <0.16 (especially with polyhydramnios), chest circumference to abdominal circumference ratio <0.6, bone bowing (although also present in viable dysplasias such as achondroplasia), multiple bone fractures, absent or hypoplastic bones, underossification of the spine, and severe micrognathia.4, 11, 12, 15, 16 It may occur that a fetus with lethal SD will survive for a prolonged period of time, especially if lethality was predicted based on ultrasound findings. In this case, clinical reassessment must be performed after birth.4, 17

Prenatal diagnosis of skeletal dysplasia

Ultrasound examination is considered an effective method for the diagnosis of prenatal-onset SD. However, studies have estimated that the sensitivity of prenatal ultrasound for the detection of particular SDs is approx. 68%.15 Few SDs are apparent during the 1st trimester, but most can be ascertained in the 2nd or 3rd trimester ultrasound. A sign of severe SD is a small crown-rump length for gestational age and increased nuchal translucency at 11–13 (+6 days) weeks of gestation if accompanied by shortened or bowed limb, a small chest and ribs, and an undermineralized skull.2, 8 More features of SD can be detected at 18–22 weeks of gestation when the main screening scan of structural defects is performed. At this time, other abnormalities such as congenital heart, renal and brain defects, as well as other anomalies comorbid with SD, can be observed.14, 18 Additional diagnostic test such as 3D ultrasound can allow visualization of dysmorphic findings in SD, such as facial dysmorphism (low-set or deformed ears, micrognathia, midface hypoplasia) and assessment of scapular anomalies, abnormal calcification patterns, and a detailed evaluation of extremities.3

Other SDs become evident in the 3rd trimester, or even after birth, further complicating timely diagnosis.2, 3, 12 Non-lethal SDs are most often diagnosed in the late period of infancy or childhood. It has been observed that an earlier onset of dysplasia corresponds with a more severe phenotype.2

Prenatal diagnosis of SDs may be determined using fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and even sometimes with low-dose fetal computed tomography (CT).2, 12, 13 Both MRI and CT are performed in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of gestation. Fetal CT can be used to depict osseous structures in greater detail, whereas fetal MRI can be used to analyze spinal anomalies or vertebral malformations.2, 3, 12, 13

There are multiple SDs that display the same prenatal features, although they have different genetic etiologies. Conversely, some SDs display different features but have similar genetic changes. Additionally, pathogenic changes in many different genes may independently correspond with the same SD (genetic heterogeneity).1, 19 An occurrence of an individual SD is rare and most SDs occur without known parental risk factors.20 For this reason, genetic diagnosis of SD in the prenatal period may be difficult regarding the targeted diagnostics.19 In clinical practice, in order to make a definitive diagnosis and provide appropriate genetic counselling to enable the choice of further management, the timing of the genetic results may be important. Thus, rapid diagnostics and data analysis are necessary.19 As a result, the next generation sequencing (NGS) method is often used in fetal genetic diagnosis.3, 4, 5, 11, 12 It has been proposed by clinicians to use a high-throughput multigene sequencing approach, such as targeted exome sequencing, whole exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS).19, 20, 21 Rapid diagnosis in trios is especially recommended. Fetal and parental DNA are sequenced simultaneously (“trios”) for faster and better interpretation of the results.19 A NGS assay can lead to the detection of pathogenic, likely pathogenic or novel variants of uncertain clinical significance in known or unknown genes. Targeted exome sequencing analyzes regions of the exome with all known disease-causing genes, which leads to minimization of the risk of identifying additional findings.19 An identification of incidental findings possible in WES and WGS may be an ethical problems. However, WES and WGS may identify novel causative genes in SD.20 Pre-test genetic counselling for all patients is needed so that they understand the aims and limitations of the test and can give informed consent. Due to the fact that not all genetic variants are clinically relevant, the results of prenatal genomic tests must be always correlated with clinical findings.2 The diagnosis of SD remains challenging, especially when there is no family history of the disorder.19 However, in all cases of suspected SD, it is necessary to collect family history, including information from at least 3 generations. Post-test genetic counselling is also necessary.20

The final diagnosis of SD may be based on imaging results, histomorphology or genetic methods.11 Some cases of SD cannot be accurately diagnosed in the prenatal or the postnatal period.

Selected examples of the most common lethal and life-limiting skeletal dysplasias

The most common types of lethal or life-limiting SDs are thanatophoric dysplasia (26%), osteogenesis imperfecta type II (14%), achondrogenesis (9%), and campomelic dysplasia (2%).22 The inheritance data, genes involved, OMIM code (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man), and Orphanet code (portal for rare disease and orphan drugs) for these conditions are summarized in Table 1. Individual lethal or life-limiting dysplasias may have more or less specific features.

1. Thanatophoric dysplasia type I or II (TD1, TD2) results from one de novo allelic mutation in the FGFR3 gene (OMIM 134934). This gene encodes one of the members of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family. The protein interacts with acidic and basic fibroblast growth hormone to influence bone development and maintenance. Mutations in the FGFR3 gene play a role in craniosynostosis and various types of SDs, such as those mentioned after achondroplasia. The incidence of TDs is 0.27 in 10,000.

The TD is characterized by shortness of limbs, generalized micromelia, a bowed femur (telephone receiver shaped femur in type I; straight femurs in type II) or other bones of the extremities, brachydactyly, a small chest, thickened soft tissues of the extremities, flattened vertebrae (platyspondyly), an unusually prominent forehead (frontal bossing) and depressed nasal bridge, and a cloverleaf skull (in type II) (Figure 2). Additionally, polyhydramnios is often present and fractures are never present; however, bowing of the femora may be mistaken for a fracture.3, 13, 15, 23, 24

2. Osteogenesis imperfecta type II (OI2) is a very severe and lethal SD. The prevalence of OI2 is unknown. Most cases result from sporadic (de novo) heterozygous mutations in the COL1A1 gene (OMIM 120150) or COL1A2 gene (OMIM 120160). These genes encode collagen type 1, alpha 1 chain and alpha 2 chain, respectively. Collagen belongs to the family of structural proteins that strengthen and support connective tissue in the body, including bone, tendon and skin.

The OI typically includes fractures, bowed and irregular thickened bones, short/normal size extremities, and a soft, thin skull. Ultrasound findings are distortions of the ribs with fractures or irregular outlines, a narrow thorax, and a compressible head due to underossification of the skull (Figure 3). Occasionally, hydrops is observed. The OI subtypes a and b are distinguished as b presents milder findings as a result of the less severe reduction of mechanical resistance of bone structure. In type IIb, the fractures are less severe, the upper limbs are less affected (due to smaller muscle mass than in the lower limbs), and the ribs have a wavy appearance, most often without fractures.

Radiographic features include Wormian bones, multiple fractures, crumbled bones, and characteristic beading of the ribs due to healing callus formation.10, 15, 22, 24, 25

3. Achondrogenesis type Ia, Ib, II (ACG1A, ACG1B, ACG2) is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the TRIP11 gene (type Ia) (OMIM 604505) or the SLC26A2 gene (type Ib) (OMIM 606718) and de novo autosomal dominant mutations in the COL2A1 gene (type II). The TRIP11 gene encodes Golgi microtubule-associated protein 210 (GMAP-210). This protein plays a role in maintaining the structure of the Golgi apparatus, in the transport of certain proteins out of cells, and is believed to be important in the developing skeleton. The SLC26A2 gene encodes a sulfate transporter that is responsible for adequate sulfation of proteoglycans in the cartilage matrix; this process is necessary for proper endochondral bone formation. Mutations in the SLC26A2 gene can cause other disorders, such as lethal atelosteogenesis (described below).

The prevalence of all ACG types is unknown. This severe SD presents with micromelia, thickened soft tissues, a poorly ossified skull, bones of the spine that are not mineralized or fully formed, flared ribs, a small thorax, and micrognathia (Figure 4). During pregnancy, polyhydramnios and fetal hydrops are often observed.3, 13, 15, 26, 27

4. Campomelic dysplasia (CMPD) results from autosomal dominant mutations in the SOX9 gene (OMIM 608160). The gene encodes the transcription factor SOX-9, which plays a critical role during embryonic development – especially in skeletal development and sex determination.

The incidence of CMPD is less than 1 in 1,000,000. This dysplasia is characterized by angulated femora or other bones of the extremities (campomelia), shortened limbs (micromelia), club feet with brachydactyly, hypoplastic scapulae and tibiae, 11 pairs of ribs, a bell-shaped chest, ambiguous genitalia (sex-reversal in males), micrognathia, flattened facial features, an unusually prominent forehead, and ventriculomegaly (Figure 5).3, 13, 15, 28 Lethality is mainly due to softness of the tracheal cartilage causing respiratory failure.

Other, less common lethal skeletal dysplasias

1. Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (ATD; short-rib thoracic dysplasia – SRTD) is very heterogeneous regarding the genetic cause and results from autosomal mutations in 1 of at least 17 genes (DYNC2H1 – OMIM 603297, DYNC2LI1 – OMIM 617083, DYNC2I2 – OMIM 613363, DYNLT2B – OMIM 617353, DYNC2I1 – OMIM 615462, WDR19 – OMIM 608151, IFT140 – OMIM 614620, TTC21B – OMIM 612014, IFT80 – OMIM 611177, IFT172 – OMIM 607386, IFT81 – OMIM 605489, IFT52 – OMIM 617094, TRAF3IP1 – OMIM 607380, CFAP410 – OMIM 603191, CEP120 – OMIM 613446, KIAA0586 – OMIM 610178, KIAA0753 – OMIM 617112). These genes encode proteins involved in the formation or function of cilia, which play a role in the signaling pathways important for the growth, proliferation and differentiation of cells during the formation and maintenance of cartilage and bone. The prevalence of ATD is unknown.

It includes mildly short limbs with mild bowing, a very narrow thorax and short ribs (a small chest), pulmonary hypoplasia, and renal dysplasia (renal cysts).1, 19, 29

2. Fibrochondrogenesis type 1 or 2 (FBCG2) results from autosomal recessive mutations in the COL11A1 gene (type 1) (OMIM 120280) or autosomal recessive or dominant mutations in the COL11A2 gene (type 2) (OMIM 120290). These 2 genes encode components of type XI collagen called the pro-alpha1 chain and pro-alpha2 (XI) chain, respectively. Type XI collagen is important in the structure of cartilage, the inner ear and the nucleus pulposus in the spine.

The incidence of FBCG2 is less than 1 in 1,000,000. It is characterized by shortened long bones (micromelia with broad metaphyseal ends of bone, described as dumbbell-shaped) with relatively normal hands and feet and flattened vertebrae (platyspondyly). Other features are a narrow chest with short, wide ribs and a round and prominent abdomen, and facial dysmorphism (prominent eyes, a flat midface with a small nose and flat nasal bridge, micrognathia).22, 30

3. Atelosteogenesis type I, II or III (AO1, AO2, AO3) results from autosomal dominant mutations in the FLNB gene (type I and III) (OMIM 603381) or autosomal recessive mutations in the SLC26A2 gene (type II). The FLNB gene encodes filamin B protein. This protein participates in normal cell growth and division, maturation of chondrocytes, and ossification of cartilage.

The incidence of all types of atelosteogenesis is less than 1 in 1,000,000. Clinical findings are severe short-limbed dwarfism (micromelia); dislocated hip, knee and elbow joints; club feet; a narrow chest; and craniofacial dysmorphism (prominent forehead, hypertelorism, a depressed nasal bridge with a grooved tip, micrognathia, and frequently a cleft palate). Polyhydramnios in atelosteogenesis type 1 and hydrocephalus in type III may occur.22, 31

4. Homozygous achondroplasia (ACH) results from homozygous mutations in the FGFR3 gene (OMIM 134934). The prevalence of homozygous ACH is unknown. Homozygous achondroplasia occurs if both parents suffer from achondroplasia. Sonographic findings are a femoral angle >130°, dysmorphic features (frontal bossing, depressed nasal bridge, macrocephaly), trident hands, and severe long bone shortening in 1st or 2nd trimester.15

Conclusions

The final diagnosis of SD may require a multidisciplinary team including obstetricians, radiologists and geneticists. In all cases of prenatally confirmed SD, genetic counseling for parents is necessary. In the case of lethal dysplasias, all possibilities of further management should be presented, both continuation of the pregnancy and termination of the pregnancy (if this solution is permitted by law).3 When the pregnancy continues, perinatal hospice care as well as palliative care after birth are proposed. If a diagnosis of lethal dysplasia or life-limiting dysplasia is suspected in the prenatal period, pediatric evaluation or multidisciplinary clinical assessment after birth is essential to verify the diagnosis. In the case of intrauterine death, physical evaluation, radiographic and autopsy examination, and storing fetal blood or other tissues as a source of DNA are recommended.2, 3

It should be emphasized that genetic counselling of the parents of a child or fetus affected by SD is necessary before the next pregnancy to discuss the recurrence risk and the possibility of preimplantation or prenatal diagnostic tests. It should also be emphasized that lethal conditions associated with de novo mutations may have less than a 1% recurrence risk (not counting the possibility of germline mosaicism), whereas SDs associated with autosomal recessive inheritance are associated with a 25% recurrence risk.