Abstract

Background. Masseter muscle pathologies include hypertrophy and the experience of pain, which clinically manifest with increased stiffness and tension. Assessment of muscle stiffness has been gaining importance among physicians dealing with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). Currently, shear wave elastography (SWE) is still often performed by radiologists, while dentists diagnose, treat and monitor TMD.

Objectives. In this cohort study, we investigated whether dentists trained to use SWE can obtain reliable measurements of masseter muscle stiffness following participation in a short training program and hands-on workshop.

Materials and methods. A group of healthy volunteers was examined by an experienced radiologist and a novice dentist before and after the training.

Results. The mean values of stiffness obtained by the operators were consistent and ranged from 10.20 kPa to 10.84 kPa. Intraobserver agreement was excellent for measurements of the radiologist (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 0.92 and 0.93, respectively). The training improved the agreement between measurements made by the dentist from poor before the training (ICC = 0.46) to good after the training (ICC = 0.89). Also, the operator agreement between the radiologist and dentist increased from poor (ICC = 0.48) before the training to good (ICC = 0.84) after the training.

Conclusions. The diagnostic accuracy of measuring masseter muscle stiffness was acceptable among dentists after the training. For this reason, the patient can be diagnosed by a single TMD specialist. This can shorten the diagnostic process and reduce treatment costs.

Key words: elasticity, temporomandibular disorders, shear wave elastography, intraobserver agreement, interobserver agreement

Background

Assessment of muscle stiffness using shear wave elastography (SWE) has been gaining importance and greater interest among physicians dealing with temporomandibular disorders (TMD).1 First, it is an objective method for the evaluation of muscle and soft tissue stiffness in general. Second, it provides repeatable and reliable measurements that can be compared with other results over the treatment period and against the normal values. Third, muscle stiffness measured with SWE reflects the condition of the muscle.2 Shear wave elastography was developed to differentiate between malignant and benign thyroid and breast nodules, but now the method is gaining wider application in other areas, including in muscles. In addition, the method is quick – a reliable examination by a skilled examiner takes about 1 min. Other methods of masseter muscle assessment have been reported to be useful (including electromyography, portable muscle hardness meter and manual palpation), but they are of less importance.3, 4 The precision of SWE is rooted in shear waves created by ultrasound push beams that lead to tissue displacement that is detected using pulse-echo ultrasound. Young’s modulus is used to calculate stiffness based on wave velocity.5

Most studies on SWE do not provide information about the specialty and experience of the examiner6, 7; however, many reports on TMD indicate that masseter muscle examinations were performed by radiologists.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Attempts have been made to engage radiologists in the monitoring of the treatment results of other pathologies of the stomatognathic system using SWE, such as bruxism and many other oral and maxillofacial diseases.12, 14 To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated SWE performed by a dentist.

The TMD consists of a group of symptoms whose classification and taxonomy are evolving.15 The current diagnostic system for TMD (Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD)) focuses on physical symptoms of the temporomandibular joints and masseter muscles (axis I) and assessment of psychosocial and behavioral factors (axis II).16 This being said, the current criteria are based on clinical symptoms and disturbed functioning, which are mostly subjective. Masseter muscle pathologies include hypertrophy and the experience of pain, which clinically manifest with increased stiffness and tension.15, 16, 17 Treatment of TMD is complex, especially if other chronic diseases coexist.18, 19 The diagnostic process of TMD can be performed by dentists and maxillofacial surgeons. Physical therapists are usually engaged in treatment. Patients benefit from this multidisciplinary approach20; however, at the same time, late or mistaken diagnosis and delayed treatment due to other reasons contribute to the chronicity of the disease.21 For this reason, methods of rapid assessment of the patient’s condition, which could be used during routine check-ups by dentists.

Due to the specificity of TMD, the diagnostic process and treatment are conducted by dentists. Currently, SWE of the masseter muscles is performed by radiologists who have limited knowledge about TMD. In contrast, in other specialties of medicine, SWE of internal organs can be conducted by physicians who treat the disease themselves and, at the same time, can use this examination as a fast, cheap and non-invasive modality to evaluate disease progression or to check the effectiveness of the treatment being used.22, 23 Furthermore, SWE can be performed by a trained radiology technician.24 Such approaches may help in designing faster pathways for diagnosis and treatment evaluation as well as reducing treatment costs.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate whether TMD specialists and dentists trained to use SWE can obtain reliable measurements of masseter muscle stiffness following participation in a short training program and hands-on workshop. We hypothesized that stiffness of the masseter muscle could be measured with similar accuracy by experienced radiologists and trained dentists with limited experience. For this purpose, interobserver agreement was analyzed.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cohort study included 51 healthy adult volunteers. Patients were recruited in September 2020 and examined through October 2020. All SWE examinations were performed by a radiologist with 7 years of experience and a dentist with limited experience who participated in a tailored training program. This 1.5-hour training program included ultrasound anatomy of the masseter muscle, technicalities of the Aixplorer Ultimate device (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France), and stiffness measurements. Masseter muscle stiffness measurements were performed twice. In the 1st round, measurements were made by the experienced radiologist and the novice dentist (30 people). After the 1st round, the dentist participated in the training seminar, which included experience sharing during which they could dispel doubts, discuss difficult cases, improve skills, and learn how to perform examinations correctly. In the 2nd round, measurements were made by the experienced radiologist and the novice dentist who participated in the training seminar (21 people). During the study, both observers were blinded to each other’s measurements as well as to the participant’s condition. Measurements conducted by the dentist were made immediately after (obligatory within 10 min) the examinations by the radiologist.

Participants

Masseter muscle stiffness was measured in an outpatient setting. Fifty-one healthy adult volunteers were enrolled in the study. Volunteers were divided into 2 groups and examined by the radiologist and dentist before and after the training. The 1st group consisted of 30 people (12 men and 18 women) with a median age of 42 years. In the 2nd round, 21 people (6 men and 15 women) with a median age of 43 years were examined.

Only subjects without signs and symptoms suggestive of TMD based on DC/TMD were included.15 The exclusion criteria were the following: any neuromuscular disorders, malignancy or pain within the masseter muscles; a diagnosis of TMD in the history with or without treatment of TMD; current treatment with muscle relaxants and/or other drugs affecting muscle function; pregnancy; and breastfeeding. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Masseter muscle stiffness expressed in kilopascals was a continuous variable. The condition of the masseter muscles was confirmed during the physical examination and medical history of the participants.

Data sources/measurement

To measure masseter muscle stiffness, the Aixplorer Ultimate device with a high-frequency linear probe SL 18–5 (5–18 MHz) with a width of 55 mm was used. Propagation of shear waves in tissues varies between 1 m/s and 10 m/s, which corresponds to elasticity of 1 kPa to 300 kPa. The tests were performed in the morning, before the first meal. The subjects were asked to lie down in the supine position, remain relaxed and comfortable during the examination, and refrain from swallowing. Before the examination, the probe was covered with an ultrasound gel for better visualization. The patients’ tissues were not compressed. The probe was placed longitudinally to the long axis of the masseter muscle, and a region of interest (ROI) with a circle size of 4 mm was positioned in the center of the muscle (the widest part of the muscle belly). The center of the masseter muscle was defined as the widest part of the masseter muscle belly and confirmed by ultrasound. With each patient, 10 measurements of the left masseter muscle and 5 measurements of the right masseter muscle were recorded and analyzed.

All measurements were performed in the same settings and conditions to ensure that the impact of other factors on muscle stiffness was eliminated. The study group included healthy people without any pathology of the masseter muscles.

Statistical methods

The collected data were stored in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2013; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) and statistically analyzed using the MedCalc v. 19.5.3 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). Means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. Reproducibility of the results was assessed using a descriptive statistic – intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).25 Intraobserver agreement was evaluated based on a comparison of the first 5 measurements and the last 5 measurements of the left masseter muscle by the same examiner. For interobserver agreement, measurements carried out by the radiologist and the dentist were compared (the first 5 measurements from before the training and the 5 measurements after the training were considered). The ICC values were interpreted as poor for ICC below 0.5, moderate for ICC between 0.5 and 0.75, good for ICC between 0.75 and 0.9, and excellent for ICC above 0.9.26 The ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using the MedCalc v. 19.5.3 based on the reliability of single ratings (k = 2), consistency, two-way model, and the same raters for all subjects. Graphical presentation of operator agreements was presented on Bland–Altman plots.

Results

The overall mean stiffness of the masseter muscle measured by the radiologist was 10.73 kPa. Table 1 presents details (means with mean SDs) of stiffness values recorded by the radiologist and the dentist before and after the training. Operator agreement, measured with ICC, between the radiologist and dentist increased from 0.48 before the training to 0.84 after the training. The ICC values are presented in Table 2.

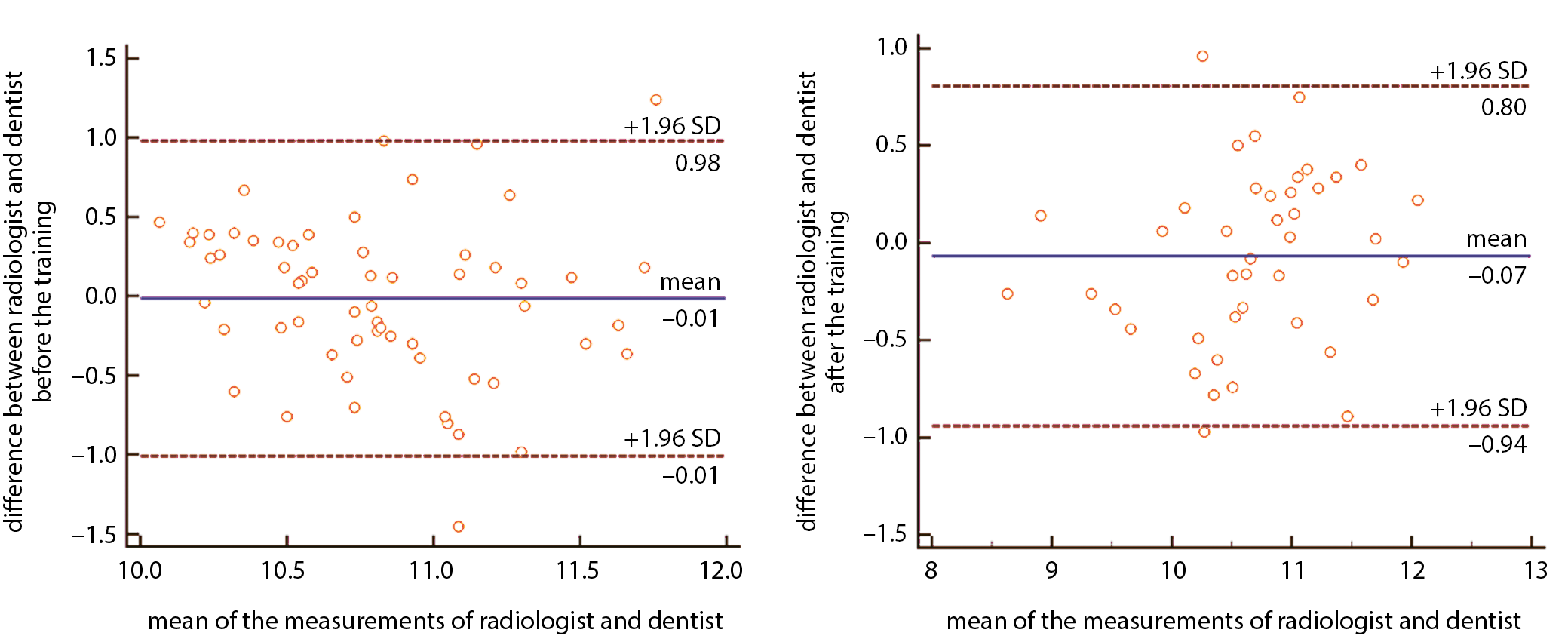

A graphical presentation of the interobserver agreement is depicted in Figure 1. The plots showed a mean difference of −0.1 kPa between operators before the training and −0.07 kPa after the training. The limits of agreement were larger before the training (from −1.01 to 0.98) than after the training (from −0.94 to 0.80).

The mean values of stiffness of the healthy masseter muscles obtained by the operators were consistent and ranged from 10.54 kPa to 10.88 kPa. However, SD values were higher for the dentist’s measurements than for the radiologist’s measurements, which indicates greater variability for the measurements of the novice operator. The operator agreement between the radiologist and dentist increased from moderate (ICC = 0.48) before the training to good (ICC = 0.84) after the training.

Discussion

The main strength of the study is that its design excluded other sources of variability, such as patient characteristics (e.g., amount of subcutaneous fatty tissue and age), known to contribute to interobserver differences.27 All examinations were performed on the same subjects and in the same environment, so the experience of the examiner was the only variable that changed during the study. We believe this is the first study aimed at evaluating the interobserver accuracy of SWE in the evaluation of masseter muscle stiffness.

Although SWE has been proven to be a reliable method that produces reproducible results in kPa, allowing for comparison between patients and different time points in the patient, its results can be affected by many factors. One factor is the experience and knowledge of the examiner and the associated learning curve.28, 29 Several approaches have been used to quantify differences among observers reporting the same measurements, with interobserver agreement being the most commonly used.

Interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility of SWE has been investigated for other organs, but not for the masseter muscle until now. For example, Ferraioli et al.30 evaluated the reproducibility of real-time SWE in the evaluation of liver stiffness. They reported an ICC of 0.93–0.95 for intraobserver agreement between measurements performed in the same subject on the same day. The ICC for intraobserver agreement dropped to 0.65–0.84 when the examination was carried out in the same subject but on different days. The ICC for interobserver agreement was 0.88. The study was performed on 42 healthy volunteers by 2 examiners. The 1st examiner, a radiologist, had more than 20 years of experience in abdominal ultrasound and 4 years of experience in elastography, while the 2nd operator had limited experience (3 months of training in ultrasound and 1 day of training in SWE). They determined that based on their experience, a novice examiner should perform at least 50 supervised scans to obtain consistent results. In another study on liver stiffness measurements carried out by Grădinaru-Taşcău et al.31 on 371 consecutive subjects, the number of reliable examinations was significantly higher for an experienced examiner than for a novice (87.4% compared to 72.8%; p = 0.001). However, this difference disappeared when overweight patients were excluded from the comparison. Their findings suggest that there might also be some factors in masseter muscle stiffness measurements that make the examination more difficult for novice operators. Those factors were not investigated in the present study. We recommend the investigation of such factors in future research.

Ultrasound examinations are the domain of radiologists; however, reports from the literature indicate that ultrasound scans can also offer clinical benefits to patients when performed by treating physicians or physicians of other specialties. A number of studies suggest that the results of ultrasound examinations for screening purposes carried out by residents with minimal training have acceptable diagnostic accuracy. Ruddox et al.32 compared the diagnostic accuracy of pocket-size cardiac ultrasound performed by experienced echocardiographers and residents with minimal experience. At the start of the study, all internal medicine residents participated in a 2-hour introductory course in pocket-size cardiac ultrasound. The comparison included data on 303 patients suspected of having heart failure or experiencing chest pain. The overall agreement reported was moderate (k = 0.50). The authors concluded that ultrasound examinations performed by residents were good enough to help with rapid differential diagnosis upon patient admission. Another study by Lucas et al.33 investigated the diagnostic accuracy of hand-carried ultrasound echocardiography performed by physicians who had participated in a 27-hour training program. After comparing the results of initial hand-carried ultrasound echocardiography with standard echocardiography, the authors concluded that the diagnostic accuracy of detecting 6 cardiac abnormalities was moderate-to-excellent. The authors also highlighted that echocardiography performed by physicians with limited experience may fill an important gap in cases where cardiac pathologies need to be diagnosed quickly, but standard echocardiography is unavailable.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, it included a relatively small number of subjects, and all were healthy volunteers who did not present any pathologies of the stomatognathic system. For this reason, we could not investigate whether SWE could be used to distinguish normal from pathological findings within the masseter muscle. Another limitation is that this study evaluated SWE only, so it did not compare this technique to other techniques used to assess the condition of masseter muscles. Also, up-to-date, normal ranges of masseter muscle stiffness have not yet been developed. Finally, no association between higher stiffness of the masseter muscle and TMD has been fully proven yet. For this reason, we could not calculate the sensitivity and specificity of this method.

Conclusions

The diagnostic accuracy of measuring masseter muscle stiffness was acceptable among dentists after a short training program and hands-on workshop. These results suggest that patients could benefit from a complete evaluation performed by one specialist during a single visit. This would shorten the diagnostic process and reduce costs.