Abstract

Background. NF-κB is an essential player in cancer biology, especially in tumor development, due to its constitutive activation, and because a four-base deletion (ATTG) in the NF-κB1 promoter region at site -94, alters mRNA stability and regulates translation efficiency. This polymorphism is a good candidate risk marker and modulator of clinical course in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). As the effect of this NF-κB1 gene polymorphism has not been studied in patients with CLL so far, the present study was undertaken to find out whether the NF-κB1 promoter -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism might be an essential genetic risk factor and/or modulatory disease player associated with CLL.

Objectives. The NF-κB1 -94 ins/del ATTG (rs28362491) polymorphism was investigated as a potential CLL susceptibility and progression factor, along with demonstration of potential modulation of the stage of clinical disease based on Rai classification.

Materials and methods. The associations of NF-κB1 -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism with CLL and its clinical manifestation in 282 Polish individuals, including 156 CLL patients, were analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers including a labeled forward primer, followed by capillary electrophoresis.

Results. A higher occurrence of the del/del homozygosity was observed among patients when compared to controls, resulting in an increase in CLL risk of more than twofold in patients carrying this homozygous genotype (OR = 2.23, p = 0.02, 95% CI = 1.14–4.37). Moreover, the del/del-positive patients more frequently presented the less aggressive disease phenotype (Rai 0), suggesting a low probability of progression to more advanced disease.

Conclusions. The NF-κB1 -94 del/del genetic variant, although associated with increased risk of CLL disease, may be associated with maintenance of disease severity in the early, mildest stage. The likelihood of disease progression may increase as the frequency of wild-type (insertion) alleles for this polymorphism increases.

Key words: nuclear factor-κB, gene polymorphism, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, cancer risk factor

Background

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common form of leukemia in the western world, with an incidence rate of 4–5/100,000. Multifactorial pathogenesis creates a complicated interaction network of internal (genetic and epigenetic) and external (for instance, microenvironmental and antigenic stimuli) factors engaged in the transformation, progression and evolution of CLL.1 Most CLL cells are inert and are arrested in G0/G1 of the cell cycle, due to the inhibition of apoptosis associated with the increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins from the BCL2 and IAP families, and the reduced expression of BAX and BAK, pro-apoptotic proteins from the BCL2 family. However, it is the progressive accumulation of tumor cells that ultimately leads to symptomatic disease. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia has a heterogeneous outcome, in which some patients progress rapidly and have short survival prognoses, whereas others have a more stable clinical course that may not need treatment for years. The most common staging systems for CLL are the Rai and Binet systems.2, 3, 4, 5 These systems define the following stages: 1) early stage (Rai 0, Binet A); 2) intermediate stage (Rai I/II, Binet B); and 3) advanced stage (Rai III/IV, Binet C). However, these systems are of limited prognostic value and the biological mechanisms involved in the clinical progression from early stages of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia are not well known.

Among the genetic factors related to CLL, the pleiotropic transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B1 (NF-κB1; p105/p50), a potential key contributor to tumorigenesis in many types of cancer, plays an important role. This redox-sensitive transcription factor regulates a number of inflammatory genes, and is an essential player in the initiation and progression of pathogenesis of many autoimmune and inflammatory diseases6, 7, 8 as well as a tumorigenesis promotor.9 It regulates the transcription of a wide range of genes involved in the immune response, cell adhesion, differentiation, proliferation, angiogenesis, cellular stress reactions, tumorigenesis, and cell survival and apoptosis.10 Specifically, the active form of the NF-κB1 gene product, protein p50, can act as a transcription factor to regulate a target gene.11, 12

Several investigators have reported the constitutive activation of NF-κB in various tumor cells and cell lines, such as in breast cancer,13 colorectal cancer,14, 15 lung cancer,16, 17 pancreatic cancer,18, 19 melanoma,11 and multiple myeloma.20 Most importantly, the activation of the NF-κB pathway mediates CLL cell survival and is further emerging as a prognostic marker in CLL.1, 21

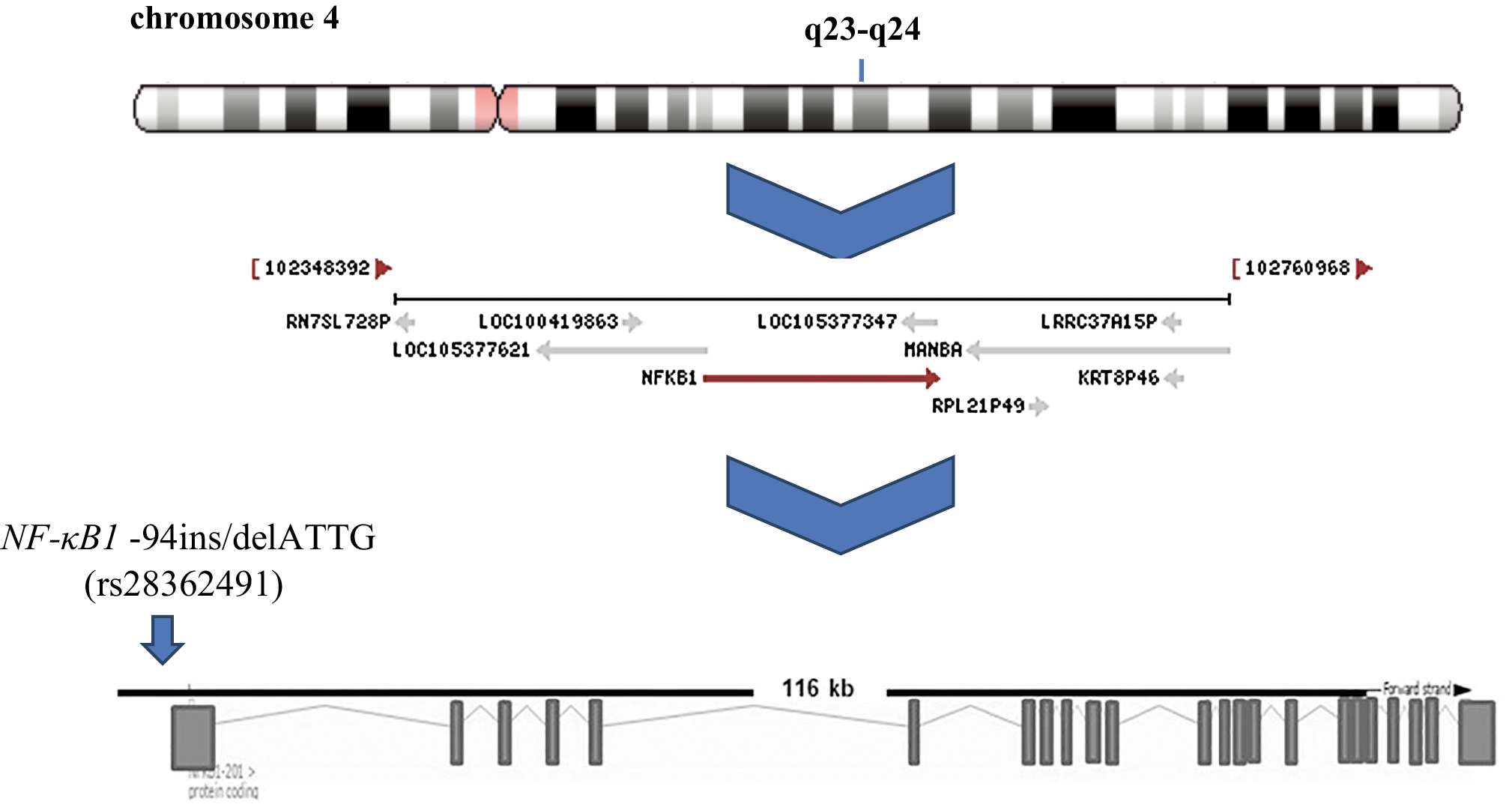

NF-κB1 (Gene ID: 4790) is mapped to chromosome 4 locus 4q23-q2422 (Figure 1) and encodes the non-DNA-binding cytoplasmic molecule p105 and a DNA-binding protein corresponding to the N-terminus of p105-p50 (OMIM: 164011). This gene is composed of 24 exons and introns varying between 40,000 and 323 bp, spanning 156 kb (Figure 1). Interindividual genetic variation is considered to be an important cancer risk and/or modulatory factor, and may impact the expression pattern encoded by the gene. Its location, molecular structure and genetic susceptibility have been extensively studied. Several variations have been described within the master regulator at the center of the NF-κB1 gene, with special interest given to rs72696119 (C>G), rs28362491 (-94 ins/del ATTG), rs4648068 (A>G), and rs12509517 (G>C). A common insertion/deletion (-94 insertion/deletion ATTG, rs28362491), located between 2 putative key promoter regulatory elements (Figure 1) (activator protein 1 and κB binding site), has a functional impact and is the most widely investigated.20 This modification occurs between 2 important regulatory elements in the promoter region of the NF-κB1 gene. The deletion of 4 bases (ATTG) reduces or prevents binding to nuclear proteins, and leads to lower transcript levels of the NF-κB1 gene, thereby changing mRNA stability and regulating translation efficiency.20

Neither numerous case-control studies23, 24, 25, 26, 27 nor several meta-analyses28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 have resolved the controversy of a potential association between the NF-κB1 -94 ins/del ATTG promoter polymorphism and cancer risk.

Objectives

We undertook this study to find out whether the -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism in the NF-κB1 promoter might be an essential genetic risk factor and/or modulatory disease player associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

The NF-κB1 promoter -94 ins/del ATTG (rs28362491) polymorphism was determined in a group of 282 Polish individuals, including 156 patients with CLL diagnosed at the Department of Hematology, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia was diagnosed according to defined clinical, morphological and immunological criteria. At the time of the study recruitment, all patients were untreated. Due to the availability of clinical data, the Rai classification was included for 144 patients. The clinical characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. One hundred and twenty-six age- and sex-matched healthy individuals that we previously genotyped35 were included as a control group.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975), as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the Wroclaw Medical University Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Genotyping

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA from lymphocytes was isolated using a DNA extraction kit (NucleoSpin Blood; Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., KG, Düren, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Identification of -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism (rs28362491) in the NF-ĸB1 gene

The primer sequences for the DNA amplification reactions were designed based on information reported by Zhou et al.11 and confirmed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (Table 2). The 5’ end of the sense primer was labeled with TAMRA (Table 2).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out in a total volume of 10 μL. The reaction mixture contained 30 μg of genomic DNA, 0.1 μM each of sense primer (forward) (Metabion International AG, Planegg, Germany) and antisense primer (reverse) (Genomed S.A., Warszawa, Poland), 1 U Taq polymerase (EURX, Gdańsk, Poland), 1× PCR buffer (containing 15 mM MgCl2) (EURX), and buffered dideoxynucleotide mixture (dNTP) containing 200 μM of each dNTP (Invitrogen, Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, USA). Amplifications were performed in a T100™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 300 s, followed by 34 cycles of 94°C for 18 s, 64°C for 18 s, 72°C for 18 s, and 72°C for 600 s. Qualitative analysis of PCR products was based on electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel, visualized under ultraviolet light (UV).

Polymorphism analysis was performed using capillary electrophoresis using an Applied Biosystems® 3130 Genetic Analyzer, equipped with 3130 Series Data Collection Software v. 4 (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific). Precise reading of the size of the tested fragments with accuracy to 1 bp was performed against GeneScan™ 500XL ROX™ dye Size Standard (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific), which includes a mixture of fluorescently labeled DNA fragments of the following sizes: 35 bp, 50 bp, 75 bp, 100 bp, 139 bp, 150 bp, 160 bp, 200 bp, 300 bp, 340 bp, 350 bp, 400 bp, 450 bp, 490 bp, and 500 bp.

Statistical analyses

All genotypes were tested for deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the χ2 test. Allele and genotype association analyses were performed using dominant and recessive genetic models. Genotype and allele analyses were performed using SHEsis software (http://analysis.bio-x.cn/myAnalysis.php).

The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis platform (SISA, http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/).

Differences were considered as statistically significant if the p-value was <0.05.

Results

Genotype distributions did not deviate from HWE, either in the patients or the controls in our cohort of Polish CLL patients (Table 3). A univariate analysis showed that patients with a recessive polymorphic homozygous NF-ĸB1 -94 del/del variant (NF-κB1 rs28362491) have a significantly modified risk of CLL. We observed that the del/del genotype of this polymorphism increased the risk of the disease 2.23-fold (χ2 = 5.63, p = 0.02, OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.14–4.37; Table 4).

Additional associative analysis of the -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism (rs28362491) in the NF-κB1 gene in CLL patients using Rai stage was carried out in a subset of 144 patients due to the limited availability of clinical data. The results are shown in Table 5. Patients with stages III and IV were analyzed together due to the small size of the groups. The CLL-prone recessive del/del genotype (χ2 = 5.63, p = 0.02, OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.14–4.37) (Table 4) was the most frequent variant in CLL patients with Rai stage 0 (27.1% > 20% > 14.3% > 18.2%; Table 5).

Statistical analysis of the genotype distribution showed differences in genotype frequencies between patients with the following stages: 0 compared to I (χ2 = 7.65, p = 0.02); I compared to II (χ2 = 6.78, p = 0.03); 0 compared to control group (χ2 = 8.00, p = 0.02); and I compared to control group (χ2 = 7.65, p = 0.02). The ins/ins genotype may protect against progression of the disease, favoring maintenance in the initial stage (Rai 0). The recessive genotype had significantly different frequencies in the healthy group and the group of patients with the lowest clinical severity (Rai 0) (χ2 = 7.58, p = 0.006, OR = 2.98, 95% CI = 1.34–6.62); The incidence of this genotype was the highest in the group with Rai 0.

Discussion

NF-κB is an essential component of cancer biology, affecting proliferation, apoptosis, vascular regeneration, inflammation, and metastasis, as well as infiltration, especially in tumors with NF-κB constitutive activation, such as those with a hematopoietic origin. Regulation of over 200 different genes by NF-κB serves as the main signal for cell survival, participating in many stages of carcinogenesis and cancer cell resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy. This has therefore become an important target of associative research on cancer pathogenesis and autoimmune diseases.11 A relationship between NF-κB1 genetic polymorphism and cancer risk has been identified, involving polymorphism variants rs72696119 (C>G), rs28362491 (-94 ins/del ATTG), rs4648068 (A>G), and rs12509517 (G>C). Among them, a common functional insertion/deletion polymorphism (-94 insertion/deletion ATTG, rs28362491), located between 2 putative key promoter regulatory elements, is the most frequently investigated genetic variant.

The connection between this polymorphism and cancer risk is inconsistently identified and appears to be divergent across different populations.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 A stratified meta-analysis revealed that this polymorphism can exert ethnic- and cancer-specific effects on cancer risk,28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 but to fully establish these differences, further large-scale and functional studies are necessary. There are several factors that may explain the occurrence of discrepancies in the results of the above studies, the most important of which are small sample sizes and diverse ethnicity, which affect the distribution of polymorphisms and environmental factors.

This genetic variant, consisting of the deletion of 4 nucleotides (ATTG) in the promoter region of the NF-κB1 gene, reduces or completely prevents binding to nuclear proteins and leads to a reduction in the level of the NF-κB1 gene transcript, thereby altering mRNA stability and regulating translation efficiency.11 In bladder cancer, the presence of the del allele (ins/del + del/del genotype) reduces NF-κB1 (p50) mRNA expression in tumor tissues.26 Moreover, patients homozygous for the deletion possess a statistically higher risk of tumor recurrence than carriers with 1 or more insertion alleles in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.26

Prior to this study, the potential role of the NF-κB1 -94 ins/del ATTG (rs28362491) genetic polymorphism in the development and course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia had not been investigated. We have shown for the first time a significant impact of this genetic variation on CLL pathogenesis. A recessive polymorphic homozygous NF-κB1 -94 del/del ATTG variant significantly modified the risk of CLL in our Polish CLL patients, increasing the disease risk 2.23-fold. Additionally, the CLL-prone recessive del/del genotype was the most frequent variant in CLL patients with Rai stage 0, so the del/del-positive patients more frequently presented with the less aggressive disease phenotype, suggesting a low probability of progression to more advanced disease. Although this is a variant associated with increased risk of CLL disease, it may also be associated with the maintenance of the disease in the early, mildest stage.

The enhanced expression and activity of p50 (NF-κB1)20, 36, 37 as a result of this polymorphism may serve as an explanation for this phenomenon. The del allele is reportedly associated with the decreased promoter activity and enhanced NF-κB1 mRNA expression,20, 36, 37 which might influence cancer development. As a transcription factor NF-κB component, p50 (NF-κB1) serves an important function in inhibiting cell apoptosis by modulating the expression levels of several survival genes (Bcl-2 homologue A1, PAI-2 and IAP gene family), which reveal the contribution of p50 (NF-κB1) signaling pathways to cellular proliferation by increasing IL-5, promoting MAPK phosphorylation and modulating cyclin D1 expression.38 Consequently, the observed association between the NF-κB1 -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism and cancer risk can be explained by decoupling this genetic variation from its roles in apoptosis and cellular proliferation by modulating the expression of p50 (NF-κB1),19, 36, 37 which is implicated through the mechanism described above.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations, including the study size, and further, well-designed studies with representative sample sizes are necessary to validate our findings. A comparative analysis of age, sex and other prognostic factors such as the mutation status of the gene encoding immunoglobulin heavy chains should be taken into account in order to prove that the NF-κB1 promoter -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism is a significant CLL risk and modulatory factor.

Therefore, firstly the relevant studies should be developed by increasing the sample size in both study groups. Second, comparative analysis of age, sex and other prognostic factors, such as mutation status of the gene encoding immunoglobulin heavy chains, should be considered.

Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the ATTG polymorphism of the NF-κB1 -94ins/del promoter may be an important factor of both risk and modulating CLL; therefore, further well-designed studies with a representative sample size are needed to definitively elucidate the role of this polymorphism to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

We suggest that the del/del polymorphism genotype -94 ins/del ATTG (rs28362491) in the NF-κB1 gene increases the risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. This may be associated with retardation of disease progression and maintenance at an early, mild stage. In populations with increased frequencies of wild-type (insertion) alleles for -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism (rs28362491) in the NF-κB1 gene, the probability of disease progression may be increased.