Abstract

Background. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway presents dysregulation in pathological scarring and mediates hypertrophic scar (HS) formation.

Objectives. The study aims to analyze the potential mechanism of long non-coding RNA NORAD (LncRNA NORAD) and microRNA (miR-26a) regulation of the TGF-β pathway in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts (HSFs).

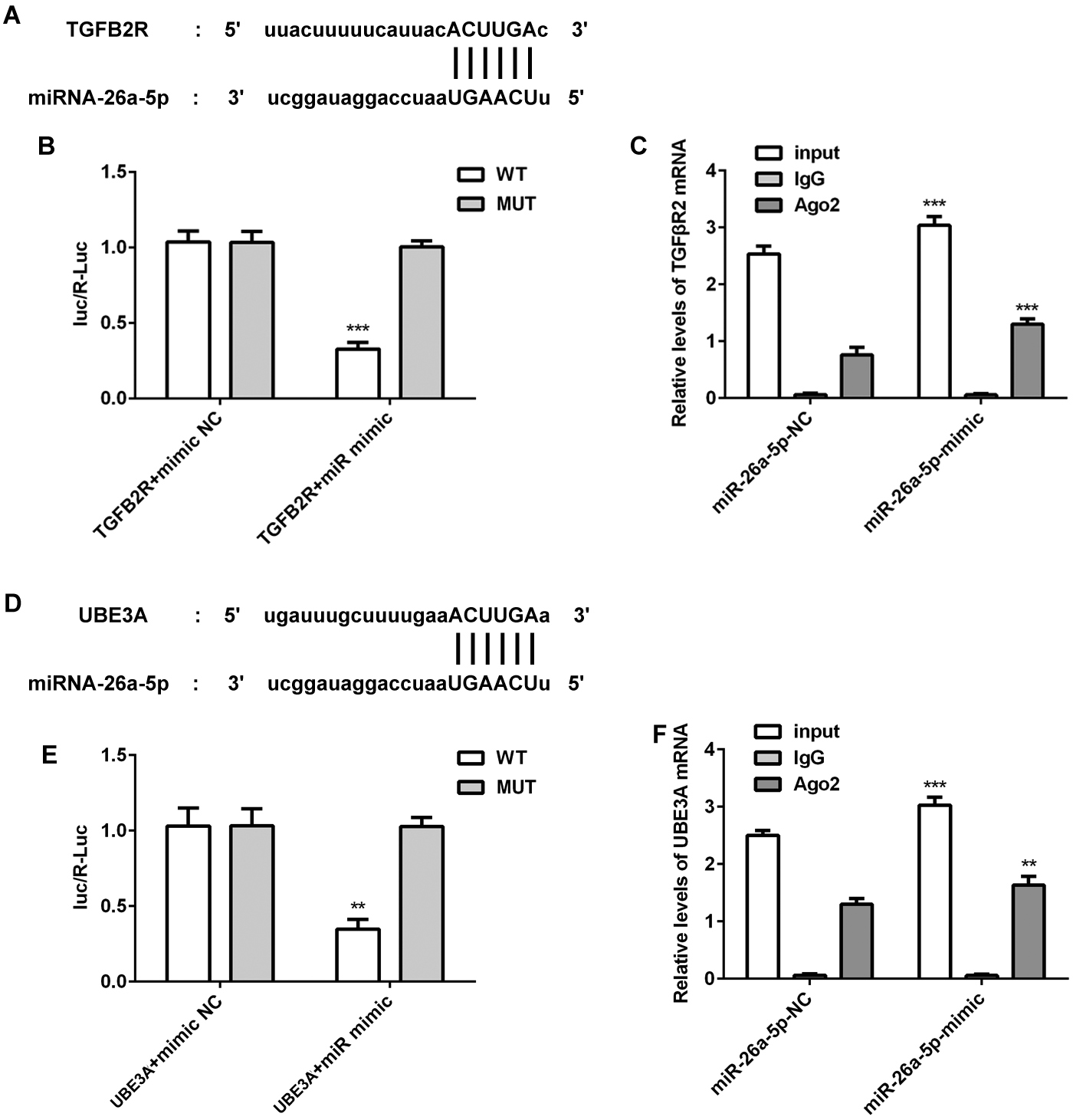

Materials and methods. Hypertrophic scar tissues were collected and assayed for LncRNA NORAD, miR-26a, transforming growth factor β receptor I (TGF-βR1) and TGF-βR2, with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or qualitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). LncRNA NORAD interfering plasmids were transfected into HSFs and induced with TGF-β1. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays were performed to assess HSF proliferation, and flow cytometry to analyze apoptosis and the cell cycle. TGF-βR1, TGF-βR2, Smad2, and p-Smad2 levels were detected using western blot (WB). The related proteins (p21, cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4)) regulating the cell cycle, and apoptosis-related proteins (caspase-3 and Bcl-2) were also detected using WB. The binding sites of miRNA-26a and LncRNA NORAD, TGF-βR2, or UBE3A were predicted using Starbase and confirmed with dual luciferase reporter assay. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) was utilized to explore the interplay of miR-26a with its target genes.

Results. LncRNA NORAD is decreased, miR-26a is increased and TGF-β receptors show abnormal expression in scar tissue. LncRNA NORAD knockdown inhibits proliferation of HSF cells induced by TGF-β1 treatment. In addition, cell apoptotic levels are markedly increased and cell numbers in G0/G1 phase are increased. Moreover, the TGF-β/Smad pathway is regulated by decreasing endogenous LncRNA NORAD levels, possibly by affecting the relative levels of TGF-βR1. p21 is notably upregulated, while cyclin D1 and CDK4 are downregulated. Apoptosis-related proteins are significantly affected. LncRNA NORAD may act as a sponge, binding miR-26a and changing its expression. Finally, RIP shows that miR-26a targets the 3’UTRs of TGF-βR2 and UBE3A.

Conclusions. LncRNA NORAD regulates HSF proliferation via miR-26a mediating the regulation of TGF-βR2/R1. LncRNA NORAD/miR-26a could be a potential target for treating HS.

Key words: hypertrophic scarring, miRNA-26a, LncRNA NORAD, TGFβR1, TGFβR2

Background

Hypertrophic scarring (HS) is a common skin disorder, mostly following burns or skin trauma, or after an operation.1 The process of collagen secretion and the metabolism of fibroblasts are strictly modulated during skin wound healing. However, the formation of HS could disrupt this balance. Hypertrophic scarring occurs under excess proliferation of fibroblasts and massive collagen deposition.2 TGF-β signaling affects cell proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) production in the process of wound healing. There is interaction between the Smad signaling pathway and non-Smad pathways, mediated by TGF-β; TGF-β homodimers interact with TGF-β receptors (TGF-βRI and TGFβ-RII), activating the Smad pathway. Phosphorylation of TGF-βR1 is necessary for this activation,3 while its ubiquitination contributes to its degradation and thus inactivates the Smad pathway. TGF-β signaling has been demonstrated to be dysregulated in pathological scarring,4, 5 and TGF-βR2 expression is increased in keloid fibroblasts.6

The TGF-β1/Smad pathway mediates the formation of HS7; suppression of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway is involved in reducing collagen deposition and inhibiting hypertrophic scar fibroblast (HSF) proliferation.8, 9 Anti-TGFβ treatment reduces ECM synthesis and Smad-3 phosphorylation in irradiated rat tissue.10 In addition, HS is markedly decreased via targeting of TGF-β2R or TGFβ-R1.11, 12 In cancer studies, the classical TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway regulates the cell cycle from G1 to S, and subsequently affects cell apoptosis.13 MicroR-26a (miRNA-26a) has been indicated to promote wound healing in fracture patients and regulate cell apoptosis in coronary heart disease.14, 15 It also has an anti-tumor effect.16 A previous study has shown that miRNA-26a causes downregulation in HS patients and suppresses the formation of hyperplastic scars.17 LncRNA-NORAD shows increased levels in breast cancer tissue and mediates the activation of TGF-β.18 Thus, TGF-β and TGF-β2R/1R expression in modulating the Smad signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the formation and development of HS. However, how the TGF-β pathway is regulated is still unexplored.

Objectives

This study intends to interrogate how LncRNA and miRNA regulate the TGF-β pathway to affect HSF formation. This study was designed to investigate the role of LncRNA NORAD in scar hypertrophy. Additionally, we also investigated whether TGF-β pathway is involved in the molecular mechanism of LncRNA NORAD.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection

Hypertrophic scar tissues and adjacent normal skin tissues (total number of cases in both groups n = 20) were surgically removed and collected, as shown in Table 1. Scar tissues included peripheral and central tissues, with intact surfaces, no rupture and covering an area of more than 3 × 2 cm. Hypertrophic scar formation was confirmed during postoperative pathological examination. The scar tissues were assayed to detect the levels of LncRNA NORAD, miR-26a, TGF-βR1 and TGF-βR2 through quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Patients did not receive any treatment before the operation. Tissue collection was conducted with the informed consent of patients signed before the operation. All experimental operations were approved by the ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, China. The scar tissue samples were obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cells

Hypertrophic scar fibroblasts (Jennio, Guangzhou, China) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal-inactivated bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Waltham, USA) at 5% CO2 and 37°C. Cells of the 3rd–5th passage were used in further experiments. The HSFs were cultured in serum-free medium overnight before recombinant human TGF-β1 treatment (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA), and then cultured in medium containing TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) for 24 h.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan). RNA was quantified using SYBR®Premix Ex TaqTM (TaKaRa), with GADPH used as the reference. Total miRNA was extracted with the mirVanaTM miRNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). Concentrations of RNA and miRNA were detected using a Microplate Reader (Invitrogen). MiRNA was transcribed into cDNA using the TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen). MiRNA levels were detected using TaqMan® MicroRNA Assays (Invitrogen), with U6 as a reference. Relative levels of LncRNA NORAD, TGF-βR1, TGF-βR2, and miRNA were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

ELISA

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm/min for 15 min. TGFβR1 (Zhen Shanghai and Shanghai Industrial, Shanghai, China), TGF-βR2 (ab193715; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and TGF-β (Mlbio, Shanghai, China) levels were detected using corresponding ELISA kits according to the respective manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm/min for 15 min. Total protein concentration was measured with the BCA method (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Target proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The bands were incubated with the following primary antibodies (all from Abcam): Rabbit anti-TGF-βR1 (ab235178), Rabbit anti-TGF-βR2 (ab184948), Rabbit anti-Smad2 (ab40855), Rabbit anti-p21 (ab109520), Rabbit anti-Cyclin D1 (ab40754), Rabbit anti-CDK4 (ab108357), Rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (ab32124) (all at 1:1000 dilution), Rabbit anti-p-Smad2 (ab216482; 1:300 dilution), Mouse anti-GADPH (ab8245; 1:5000 dilution), and Rabbit anti-Caspase-3 (ab13847; 1:500 dilution) at 4°C overnight, which then were washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) twice. A secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (ab6721) or Rabbit Anti-Mouse IgG (ab6728); 1:10000 dilution; Abcam) was then applied and the bands incubated for 2 h. After the bands were washed twice, electrochemiluminescence (ECL) was used to develop the color. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA) detected the gray value of each protein band. The relative expression of protein was calculated, taking GADPH as a reference.

Plasmids transfection

NORD knockdown plasmids (sh-NORD) or a negative control (sh-NC) were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. LncRNA NORAD overexpression vectors (LncRNA NORAD vector) or a control (empty vector) were transfected into cells. MiRNA-26a mimic or a control mimic (mimic NC) were also transfected into cells. All plasmids and mimics were purchased from IGE Biotechnology (Guangzhou, China). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were used in further experiments.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

The HSF cells were seeded into a six-well plate (5 × 10^4 cells/well). Culture medium without antibiotics was added to each well and the same number of cells were inoculated in each well. The confluent degree of cells should reach approx. 85–90% during transfection. Luciferase reporter vectors were constructed through respective cloning of LncRNA NORAD, TGF-R2 or UBE3A into pmirGLO plasmids. The putative binding sites of miR-26a on the corresponding pmirGLO-WT plasmids were mutated using a QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, San Diego, USA) and construct pmirGLO-Mut plasmids. A miR-26a mimic or miR-NC was transfected into HSF cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, luciferase activity was detected using Dual Luciferase® Reporter Assay System kits (Promega, Madison, USA).

CCK-8

TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) peptides were used to activate HSF cells. Cell proliferation was detected using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The HSF cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 10^3 cells/well) and treated using CCK-8 solution (10 µL/well; Beyotime). After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the absorbance at 490 nm was detected using a microplate reader.

Flow cytometry

Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells seeded into a six-well plate were digested with trypsin and centrifuged at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were washed with pre-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times. Annexin V assay was used in combination with PI labeled HSF cells to distinguish apoptosis and death at different stages of the cell cycle. Annexin V−/PI− and Annexin V+/PI− fluorescence assays were used to indicate living cells and early apoptotic cells respectively, whereas Annexin V+/PI+ fluorescence assay indicated dead cells and apoptotic cells in the middle and advanced stages. Cells were stained using FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide (Becton Dickinson Bioscience, San Jose, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidance. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded into a six-well plate and digested using trypsin. The cell suspension was collected and centrifuged at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and cells were incubated with 70–80% pre-cold ethanol (5 mL) at 4°C overnight. The cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min; then, the ethanol was flushed out using PBS or staining solution. Afterwards, the cells were suspended into 0.5 mL PI/RNase solution (Becton Dickinson Bioscience) and incubated without light for 15 min. The cell cycle was detected with flow cytometry within 1 h.

RIP

Cells were washed twice using cold-PBS, then centrifuged at 1000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. Afterwards, cells were lysed using RIP lysis buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was incubated with anti-Ago antibody or lgG (Merck Millipore, Burlington, USA) as a control at 4°C. Magnetic beads conjugated with protein A/G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) were added into the supernatant. Proteinase K Buffer was used to resuspend the beads and antibody complex. The related RNA in the immunoprecipitation was collected and detected using quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Comparison among groups was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

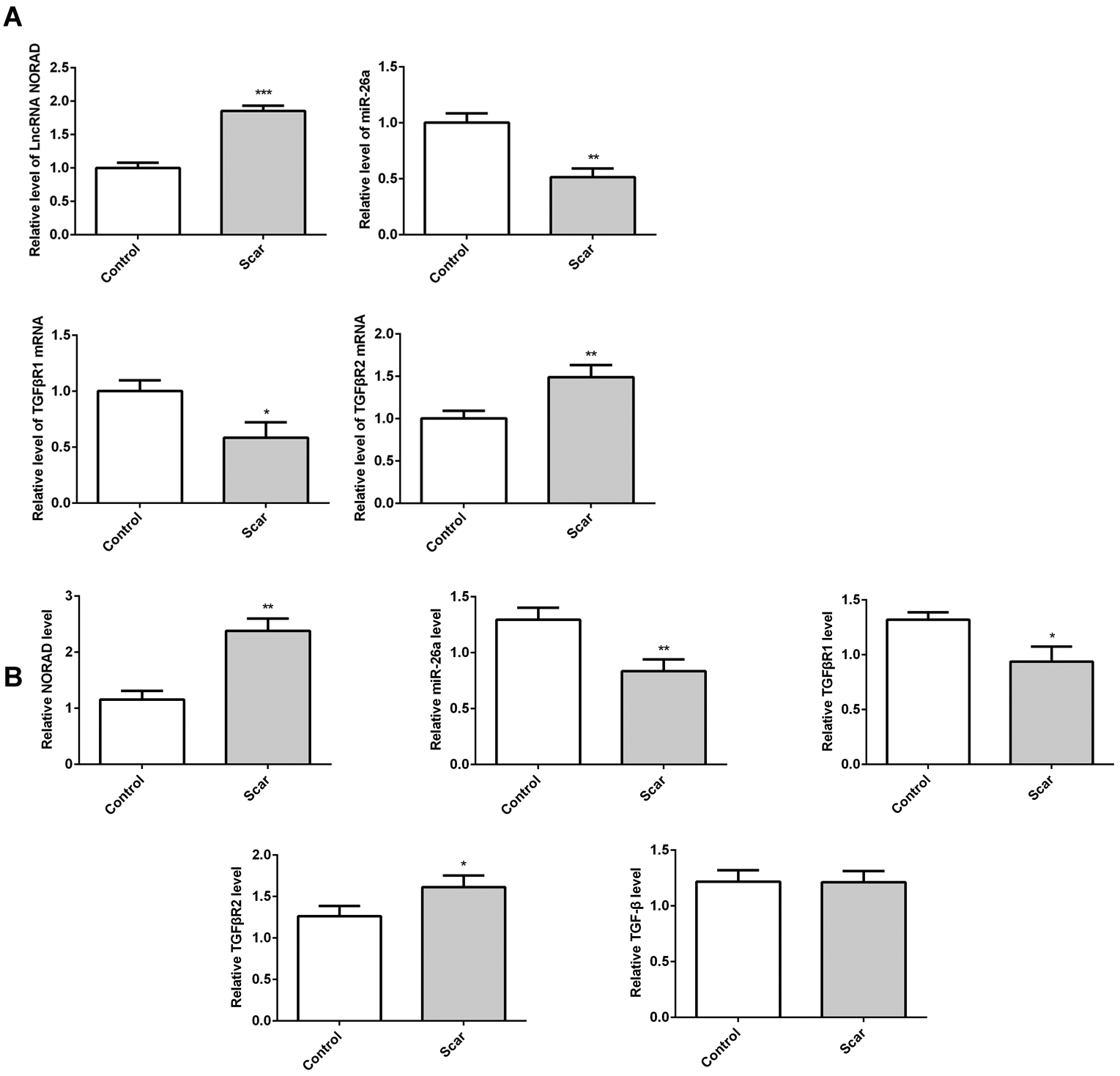

LncRNA NORAD and miR-26a show dysregulation in HS tissue

The qPCR results showed that LncRNA NORAD was significantly upregulated and miR-26a was downregulated in intermediate scar tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. TGF-βR2 levels were increased, as demonstrated by qPCR and ELISA (Figure 1A,B). However, TGF-βR1 levels were reduced. TGF-β showed no significant change in the HTS group compared to the control group.

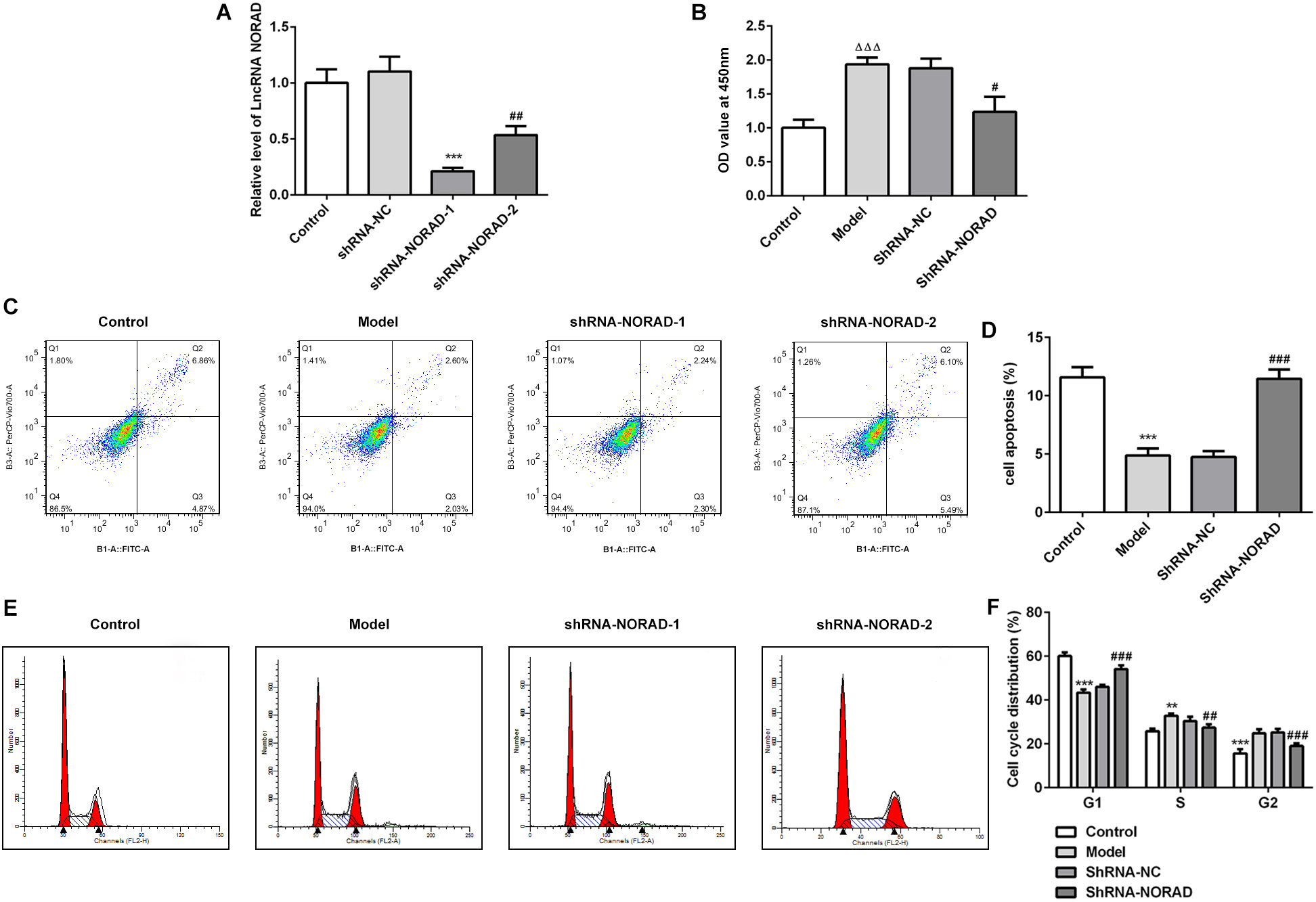

LncRNA NORAD knockdown

suppresses cell proliferation

and facilitates cell apoptosis

TGF-β1 was used to induce HSF proliferation, and qPCR was used to evaluate the transfection efficacy of shRNA-NORAD-1 or shRNA-NORAD-2. The results showed that shRNA-NORAD-1 has a greater inhibitory effect on NORAD expression than shRNA-NORAD-2 (Figure 2A). Thus, shRNA-NORAD-1 was used in all further experiments. Additionally, the CCK-8 assay demonstrated that cell proliferation ability was markedly decreased by silencing LncRNA NORAD (Figure 2B). Silencing LncRNA NORAD promotes cell apoptosis, as shown by comparing to results from the ShRNA-NC group (Figure 2C,D).

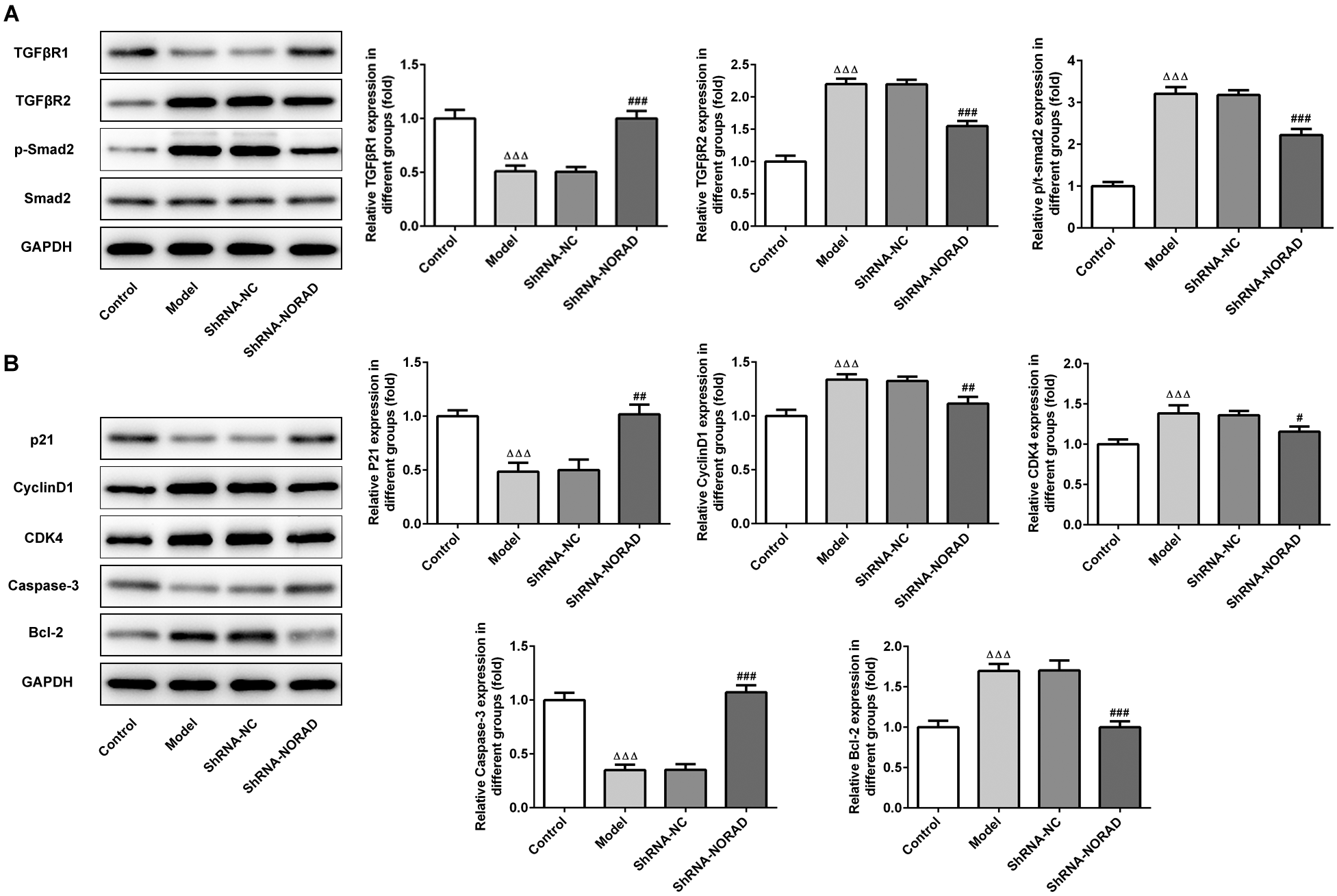

The results of flow cytometry revealed that decreasing endogenous LncRNA NORAD significantly increased the proportion of cells in G0/G1 phase compared with the control group. Simultaneously, the proportion of cells in S and G2/M phase was reduced (Figure 2E,F). These results imply that LncRNA NORAD affects the G1 arrest of HSFs treated with TGF-β1. That is to say, G1 arrest is significantly promoted by a decrease in endogenous LncRNA NORAD expression (Figure 2E,F). TGF-βR1 levels were significantly increased, while TGF-βR2 and p-Smad2 were markedly decreased (Figure 3A). These results suggest that decreasing endogenous LncRNA NORAD levels may suppress the TGF-β pathway. Proteins regulating cell cycle and cell apoptosis-related proteins were also significantly affected (Figure 3B). The above findings indicate that LncRNA NORAD knockdown promotes G1 arrest by regulating p21/cyclin D1/CDK4, and by modulating the apoptosis pathway by increasing pro-apoptosis protein caspase-3 and decreasing anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2.

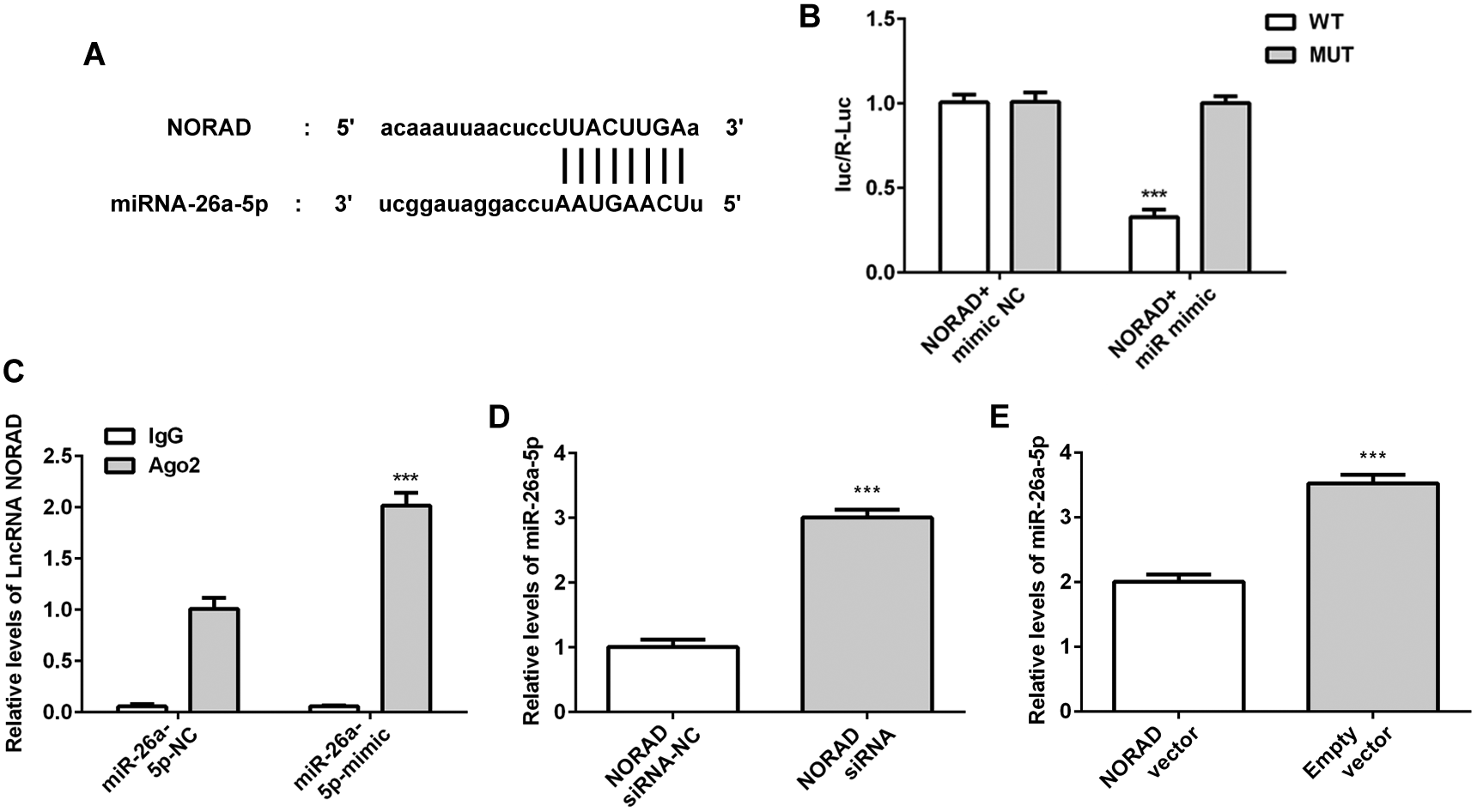

LncRNA NORAD as a sponge

regulates miR-26a level

The Starbase database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) predicts that miR-26a could target LncRNA NORAD (Figure 4A). Therefore, a cell experiment was performed to investigate whether miR-26a could bind to LncRNA NORAD, and whether LncRNA NORAD could act as a sponge of miR-26a and regulate its biological function. The sequence of LncRNA NORAD was inserted downstream of a luciferase gene to establish wt-NORAD plasmids. In HSF cells co-transfected with wt-NORAD and a miR-26a mimic, luciferase activity was significantly decreased compared to the mut-NORAD and miR-26a treatment groups, suggesting an interaction between miR-26a and NORAD (Figure 4B). Also, the RIP assay showed the LncRNA NORAD level in the miR-26a mimic group was significantly higher than that of the miR-26a-NC group when anti-Ago2 antibody was used to treat the supernatant (Figure 4C). In addition, LncRNA NORAD markedly affects miR-26a level (Figure 4D,E). Thus, LncRNA NORAD functions as a sponge of miR-26a to inhibit miR-26a expression.

miR-26a binds to the 3’UTR of TGF-βR2

We analyzed whether miRNA-26a targets the TGF-β pathway. Starbase predicts that miR-26a could bind to the 3’UTRs of TGF-β2 and UBE3A (Figure 5A,D). The luciferase reporter assay revealed miR-26a can bind to the 3’UTR of either TGFR2 or UBE3A, as it reduces the luciferase activity of both wt-TGFR2 and UBE3A (Figure 5B,E). The RIP assay demonstrated that TGF-βR2 and UBE3A levels in the miR-26a mimic group were distinctly higher than in the miR-26a-NC group when anti-Ago2 antibody was added to the supernatant (Figure 5C,F). These data imply that miRNA-26a post-transcriptionally regulates TGF-βR2 and UBE3A.

Discussion

Our data showed that LncRNA NORAD exhibited a significant increase and miR-26 showed an obvious decrease in scar tissues. We also found reduced TGFβ-R1 and enhanced TGFβ-R2 expression in scar tissues relative to a control group. The involvement of LncRNA in the activation of TGFβ signals has previously been investigated.18 Further investigation of the mechanism of LncRNA NORAD in HSF cells revealed that decreasing endogenous expression of LncRNA NORAD significantly increased p21, and downregulated cyclin D1 and CDK4 levels. Cyclin D1 and CDK4 could form a complex and allow cells to bypass G1 phase, whereas p21 could also suppress cells from entering S phase via inhibition of cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) activity. The CDK activity is positively regulated by cyclin D and negatively regulated by cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI). Thus, LncRNA NORAD silence facilitates G1 arrest, possibly via upregulating p21 levels, and downregulating CDK4 and cyclin D1 expression. A study has shown that inhibition of cyclin D1 and CDK4 could mediate G1 arrest in HSF cells.19 Additionally, upregulation of p21 expression contributes to the suppression of apoptosis in HSF.20 Collectively, these results indicate that LncRNA NORAD knockdown significantly boosts apoptosis and G1 arrest in TGF-β-stimulated HSF.

In this study, we discovered that LncRNA NORAD was dramatically enriched in the complex precipitated by anti-Ago2 in HSF cells overexpressing miR-26a-5p, suggesting an interactive relationship between LncRNA NORAD and miR-26a-5p. In addition, LncRNA NORAD overexpression or silence markedly regulated miR-26a-5p. Therefore, LncRNA NORAD could be a sponge of miR-26a-5p in that it regulates the biological activity mediated by miRNA-26a.

A luciferase reporter assay was applied to confirm our prediction that miRNA-26a targets the 3’UTR of TGF-βR2 and UBE3A, proving that miRNA-26a could regulate TGFβ-R2 and UBE3A expression, and in turn influence cell proliferation and apoptosis. The excessive proliferation of HSF causes abnormal ECM synthesis.21 TGF-β has been demonstrated to be involved in the process of wound repair and healing, which includes extravagant proliferation of fibroblasts.22 The TGF-β1/TGF-βR1/Smad3 pathway is reported to promote HTS formation.23 Medicine targeting the TGF-β/Smad pathway could suppress fibroblast proliferation or reduce scar formation.24 Changing the expression of endogenous miRNA regulates apoptosis, possibly by affecting the TGF-β pathway in HSF.25 Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor 2 (Smurf2), known as one of the homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus (HECT) family E3 ligase members, is involved in the ubiquitination of TGF-βR1.26 Ubiquitin and proteasome degradation of TGF-β receptors negatively regulates the TGF-β pathway.27 Therefore, Smurf2 could negatively regulate TGFβ-R1 levels through ubiquitin induction. Research has demonstrated that the degradation of TGFβ-R1 induced by Smurf ameliorates TGF-β signals,28 thereby affecting the development of HTS.29 A study has shown that miRNAs enhance the TGF-β signal pathway through targeting Smurf2 mRNA and inhibiting its translation.30 Therefore, it follows that miR-26a could regulate TGFβ-R1 though Smurf2 and affect TGF-β signals based on the experimental data and published studies.

Limitations

There is still lacking in vivo evidence to support this conclusion about the regulatory mechanism of LncRNA NORAD in scar hypertrophy in vitro, which requires further study.

Conclusions

TGF-β signals have been shown to be transmitted through the engagement of TGFβR2,31 and TGF-β signaling can be significantly activated with the deubiquitination of a TGF-β receptor.32 Collectively, TGFβ-R1/R2 plays a substantial role in regulating the TGF-β pathway, and miRNA-26a could be a potential target for treating HTS. In this study, we show that miRNA-26a can regulate the expression of TGF-βR2 and Smurf2 by binding to their 3’UTRs. Previous studies have indicated that miRNA regulates the expression of protein through suppressing its translation and recruiting other proteins to induce degradation. Our study confirms that LncRNA NORAD regulates HSF proliferation and apoptosis, possibly via miR-26a mediating TGF-βR2/R1, which provides a novel insight for understanding the pathological mechanism of HTS. In conclusion, LncRNA NORAD/miR-26a could be utilized as potential targets for new HS treatment.