Abstract

This review aims to characterize the dualistic role of autophagy in both the suppression and propagation of carcinogenesis. The process of autophagy is responsible for maintaining the delicate balance between the survival and death of a cell, and in the past years it has been studied profoundly. It has been proven that the role of autophagy in maintaining genomic and structural integrity can lead to the suppression of carcinogenesis in its early stages. However, once carcinogenesis has occurred, the process of autophagy may contribute to the survival of tumor cells and, consequently, lead to tumor progression. Additionally, autophagy can modulate the response of the tumor cells to therapy, leading to radiotherapy and chemotherapy resistance or reduced susceptibility to anticancer drugs that propagate autophagy-related cell death. Although the role and course of autophagy are not yet fully known, the essence of it seems to be within our grasp. We have observed the identification of an increasing number of autophagy-related genes (ATG). Therefore, more research concerning its molecular course and potential applications in cancer treatment and prevention needs to be conducted.

Key words: oncogenes, cancer progression, autophagy, chaperons

Introduction

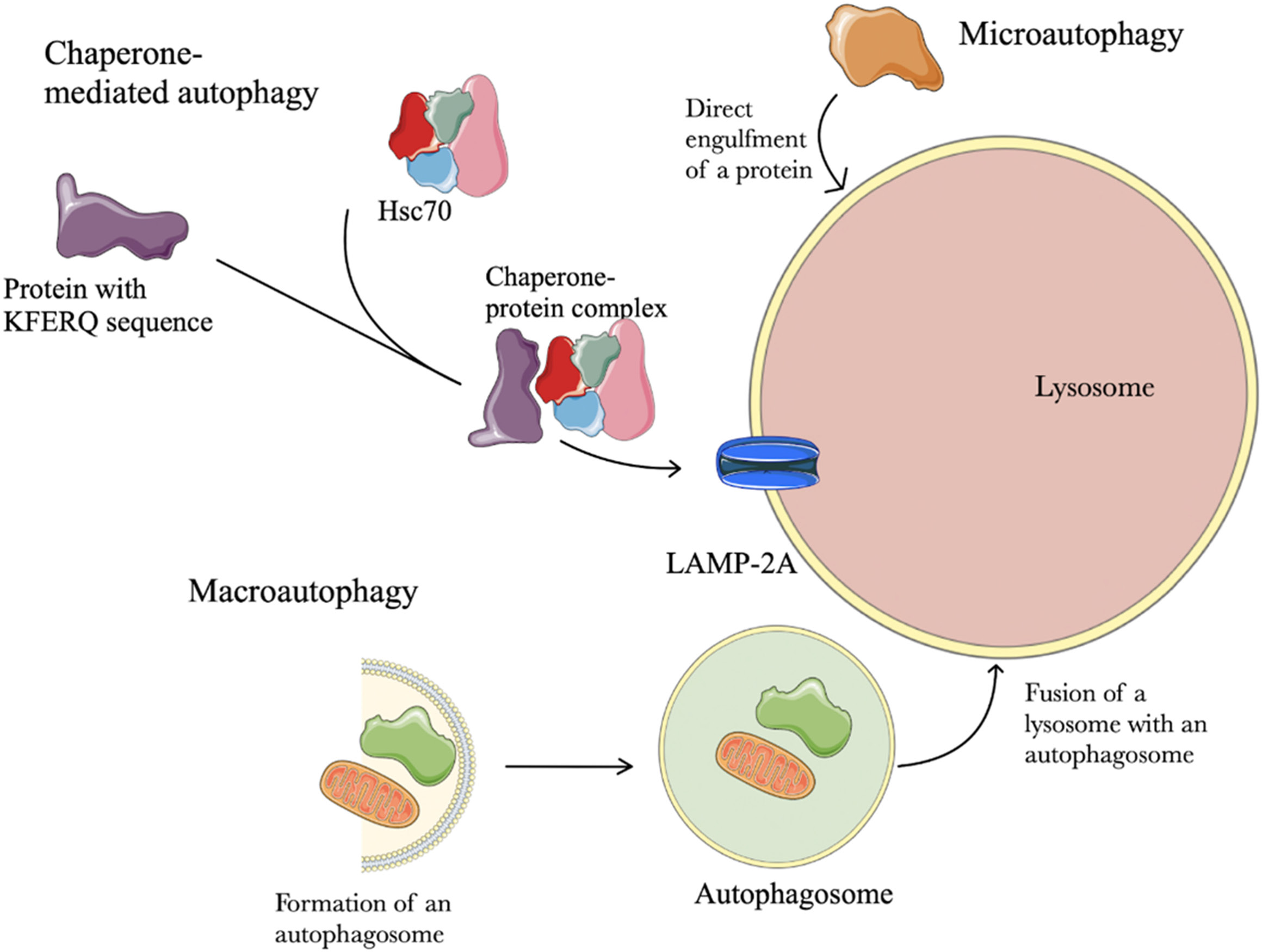

Autophagy is considered to be the process responsible for keeping a cell in a state of energetic and material well-being,1, 2 and in the beginning it was studied as such. Over time, researchers started noticing other cellular and molecular processes that are influenced by or dependent on autophagy. The term is derived from Greek, meaning “self-eating” because of the observed digestion of the structures of the cell. As mentioned above, autophagy was thought to be a mechanism cells use during starvation, metabolic stress,3 and degradation of misfolded proteins,4 organelles and intracellular pathogens. During years of research, the role of autophagy in cellular senescence and necrosis prevention5 has been identified, opening up a new field into the possible roles of this process. Researchers have distinguished 3 types of autophagy: microautophagy, macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA).6 All types lead to the common end stage of lysosomal degradation of cellular structures and proteins (Figure 1). The term microautophagy describes the process of direct invagination of a material meant to be digested by a lysosome. Macroautophagy uses unique structures called autophagosomes which are double-membrane vesicles used to deliver the material into lysosomes. The 2 vesicles fuse to form an autolysosome. In the process of the chaperone-mediated autophagy, chaperones recognize and bind to proteins containing a KFERQ motif. Then, they are translocated across the lysosomal membrane using the LAMP-2A protein, where they are unfolded and degraded.7, 8 Both micro- and macro- autophagy are involved in the degradation of large and small structures, and may be selective or nonselective. Chaperone-mediated autophagy is limited to proteins residing in the cytoplasm and does not apply to larger structures like organelles.

Objectives

This review aims to delineate the dualistic role of autophagy in the suppression and propagation of carcinogenesis. We describe the role of autophagy in maintaining the balance between cell survival and death. Based on the available literature, we summarize the role of autophagy in carcinogenesis and the possible modulation of the tumor cell response to therapy.

Methodology

This review was prepared after a literature search was conducted using PubMed, Mendeley, Google, Scopus, Embase, and AccessMedicine. The literature search was limited to articles published between 2001 and 2021, using the following search terms: autophagy regulation, macroautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, autophagosome formation inhibition, autophagy inhibition, and autophagy and treatment.

The complexity

of autophagy function

Autophagy, or more specifically the deregulation of it, is considered an essential factor in the development of many types of diseases.6 The different types of autophagy and its selective and nonselective mechanisms of action result in an astounding diversity of diseases it may play a role in. The list of diseases that deregulated autophagy may be involved in, as a meaningful contributive component, is constantly getting longer.9 Autophagy occurs on a basal and constitutional level. The role of the basal level has been recently highlighted as a home keeping mechanism for the cell. Different tissues demand various levels of autophagy. Therefore, tissues that do not divide after differentiation, such as neurons and myocytes, are acutely sensitive to the inhibition of autophagy. However, some tissues are less prone to the absence of autophagy. Neurodegenerative disorders are among the most commonly mentioned pathologies proven to be linked to autophagy.10, 11, 12 However, the main focus of this paper is to provide a highly researched description of the relationship between autophagy and cancer. Nowadays, we can state that autophagy plays a noteworthy role in both cellular protection against cancer and the growth of a tumor itself.3 Autophagy supports tumor growth by promoting the survival of neoplastic cells that have to cope with stressors as a result of their rapid proliferation, such as hypoxia and nutrient starvation. Its protective role is fulfilled by the inhibition of chronic inflammation and necrosis. The more critical roles of autophagy are removing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that emerge from dysfunctional mitochondria, causing intense damage to the cell, preventing cellular oncogene-induced senescence, and maintaining genomic stability.13 Thus, a conclusion may be drawn that autophagy plays a role in the early stages of tumor progression and even initiation.

The induction and regulation of autophagy

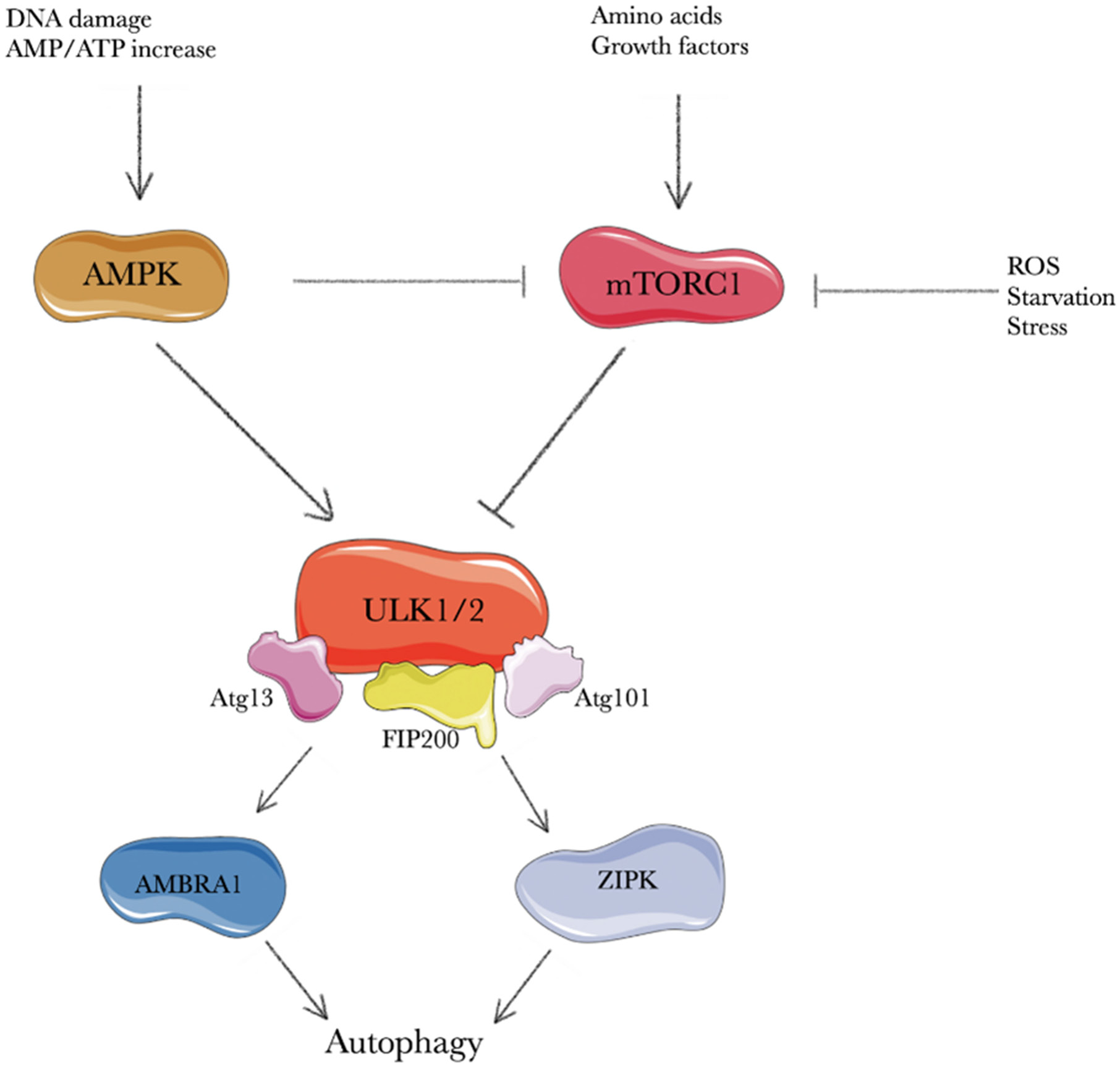

Autophagy consists of 5 main stages: initiation, elongation, maturation, fusion, and degradation. The complex process of initiation has many different triggers. Extensive investigations have been conducted on yeast and have established that nitrogen, carbon and nucleic acids starvation are all activators of autophagy, although some are stronger than others.14 In yeast, the starvation of compounds essential to cell survival is a strong stimulus to initiate autophagy, as is the same for mammalian cells. The starvation of amino acids and energy, the absence of growth factors, and the accumulation of misfolded proteins, ROS, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and calcium play a significant role in autophagy induction.15 Most of the triggers suppress the common pathway mTORC1, referred to as a nutrient-sensing kinase, but some have been proven to activate other signaling routes independent of mTORC1.16 The presence of a trigger begins the complex process of autophagy (Figure 2). The process is controlled by over 30 autophagy-related (Atg) proteins.17 The Atg proteins are essential to control the correct course of autophagy. Numerous Atg genes have been proven to play an important role in tumor suppression. Consequently, decreased levels of many Atg proteins are found in tumor cells.18 Under “normal” conditions, mTORC1 suppresses autophagy via mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of Atg13 when nutrient levels are sufficient.19 However, in the presence of a trigger, the mTORC1 pathway is suppressed and the AMPKs (considered the most vital activator of autophagy) pathway allows autophagy to proceed.

The AMPK is the principal energy sensor for a cell and is activated when AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP ratios increase, thereby directly linking the process of autophagy with energy starvation.20 The AMPK has been proven to have a dualistic role in the induction of autophagy. By suppressing mTORC1, AMPK indirectly induces autophagy, but can also induce phosphorylation ULK1/2 to directly activate the process.21 The ULK1 is one of 5 orthologs of Atg13 found in yeast. So far, ULK1 and ULK2 have been proven to be involved in the induction of autophagy, and despite slight differences in function and constitution between them, they are often referred to interchangeably. The ULK1/2, Atg13, FIP200, and Atg101 proteins form the so-called ULK1/2 complex.22 Although the exact course of interaction between these proteins has not been fully elucidated, it has been suggested that ULK1/2 requires both Atg13 and FIP200 for stability and correct function, as both enhance its kinase activity.23 The role of the ULK1/2 complex seems to be the phosphorylation of 2 proteins: AMBRA1 and ZIPK.24, 25 The effect of these interactions causes the downstream events required for phagophore formation. As shown above, the relationship between mTORC1 and AMPK activity plays a vital role in autophagy induction and suppression. Although these are the most researched regulators of autophagy, they are not the only ones.

The course of macroautophagy

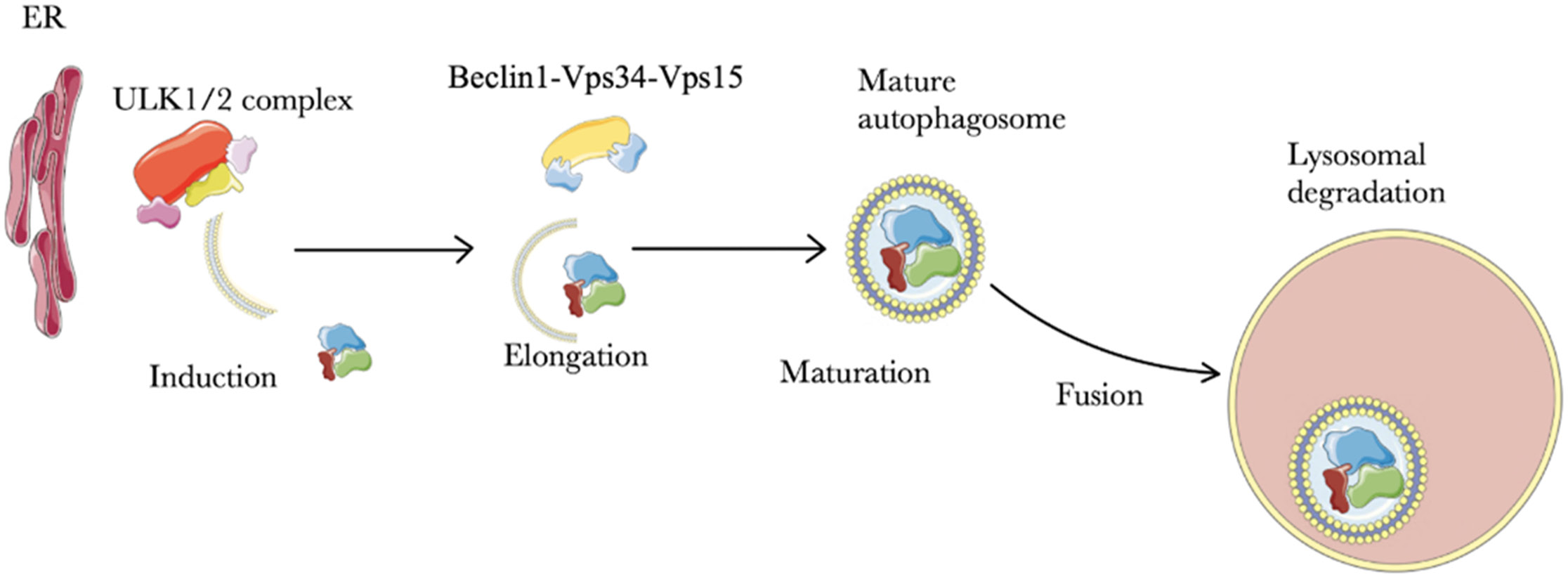

The induction of autophagy allows for the further stages to proceed. After the formation of the phagophore, elongation occurs, resulting in the creation of an autophagosome. Next, the whole structure undergoes maturation. Finally, the fusion of the autophagosome with a lysosome occurs, allowing for the final stage of autophagy to occur – degradation (Figure 3). The phagophore (also known as the isolation membrane) is a double-membrane structure that is the first traceable structure in autophagosome creation.26 Unfortunately, after years of research and despite advances in technology, its origins remain unclear. It is believed that a phagophore forms de novo and is distinct among organelles.27 The current literature has shown phagophores to form close to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), meaning they could use it as a nucleation site. It has been established that the ULK1/2 complex is responsible for creating a membrane curvature, while other Atg proteins fold it into 2 and detach it from the site of origin.28 After nucleation, the phagophore grows using other organelle membranes during the elongation stage. The mitochondria, ER and Golgi’s complex have been suggested to be involved in the elongation stage.29 The growing phagophore encloses macromolecules of cytoplasm destined for degradation forming the autophagosome – a double-membrane vesicle.30 After maturing, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome and the degradation occurs. During degradation, the contents of the autophagosome are broken down by lysosomal hydrolases.31

Importantly, the so-called Beclin-1 protein, a BH3-only domain protein, has a vital role in the nucleation of phagophores and the maturation of the autophagosomes.32 Beclin-1 consists of 3 domains: Bcl-2-homology-3 (BH3), coiled coil (CCD) and the so-called evolutionary conserved domain (ECD).33 Together with many cofactors (i.e., Rubicon, AMBRA1, UVRAG, Atg14L), it regulates the lipid kinase Vps-34 and promotes the formation of the Beclin1-Vps34-Vps15 (Vps15 is referred to as p150 by some authors) complex.34 The Vps-34 is a class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI(3)-kinase). Interestingly, it is the only mammalian PI(3)-kinase, as no other PI(3)P producing enzyme has been found. The PI(3)P has been proven to be essential in the course of autophagy.35 The Beclin1-Vps34-Vps15 structure constitutes the core of other complexes, known as PI3KC3 complexes (class III phosphoinositide-3-kinase complexes), which play various roles in the autophagy. The PI3KC3 complex I is formed with Atg14L and has an essential role in autophagosome formation, especially in its early stages (i.e., phagophore formation).36 This complex is further regulated by other factors, such as AMBRA1, NRBF2 and VMP1.37 The AMBRA1 is a positive regulator of autophagy and is likely activated by the ULK1/2 complex.38 In the later stages of autophagy, Atg14L is substituted by UVRAG and the complex II PI3KC3 is formed.39 This complex has been found to have a role in autophagosome formation and maturation. The 3rd complex, involving core proteins and UVRAG, also contains Rubicon.40 Although its role has not been well-defined, it has been reported to negatively regulate autophagy via autophagosome maturation suppression.41 It is important for further research to focus on the complex interactions between these proteins, as some of these compounds are known for their ability to modulate PI3KC3 complexes and, therefore, be used in cancer therapy with hopes of suppressing autophagy in tumor cells.

One of the Beclin-1 domain names is derived from its ability to bind to Bcl-2 proteins. The Bcl-2 is a large family of proteins known for their role in apoptosis and autophagy regulation.42 It has been established that under “normal” circumstances Bcl-2 binds to Beclin-1, inhibiting its ability to interact with Vps34.43 But once autophagy propagating conditions occur, Bcl-2 dissociates from Beclin-1, allowing autophagy to proceed. Other members of the Bcl-2 family can interact with Beclin-1 as well, such as Bcl-XL, Bcl-w and Mcl-1.44 This suggests that the interaction between Beclin-1 and any given Bcl-2 family protein may influence autophagy differently. Furthermore, the Bcl-2 family directly links autophagy and apoptosis.45 Additionally, short periods of nutrient deprivation stimulate the dissociation of the Beclin-1-Bcl-2 complex propagating autophagy. With a prolonged exposure to these conditions, the Bax-Bcl-2 complex dissociates and propagates apoptosis.46 It is important to note that BH3-mimetic molecules can disrupt the Beclin-1-Bcl-2 bond stimulating autophagy in cells in the correct clinical situation. Aside from autophagy, those molecules can also induce apoptotic death in cancer cells through their effect on the Bax-Bcl-2 complex.47

CMA role in cancer biology

Chaperone-mediated autophagy in non-transformed cells has been proven to be a cancer-preventive process; it acts through degrading proteins of oncogenic activity and facilitating cell death.48 A decrease in CMA with age has been described.49 The intensity of CMA increases in most neoplastic cell lines as do the levels of a component of CMA, namely lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2A).50 Inhibition of CMA in cancer cells reduces their tumorigenicity, cell survival and metastatic potential.50 The pro-oncogenic effect of elevated levels of CMA components is dependent on the tumor type and stage. The function of CMA as a protein quality inspector explains the increased tumor cell survival and resistance to the conditions of their microenvironment.51 Moreover, CMA has been proven to be capable of degrading specific proteins that are responsible for antiproliferative effects (Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoE),51 in addition to tumor suppressor proteins (REF, MST1)52 and pro-apoptotic proteins such as PUMA (BBC3- Bcl-2 binding component 3).53 A high affinity of CMA for enzymes involved in the glycolytic cycle has also been described.54 Degradation of these enzymes leads to the accumulation of glycolysis intermediates that promote proliferation. The inhibition of CMA causes oxidative stress, apoptosis and higher susceptibility to chemotherapeutics. Thus, CMA inhibition is considered a possible future cancer therapy.48

Relation between autophagy

and cancer

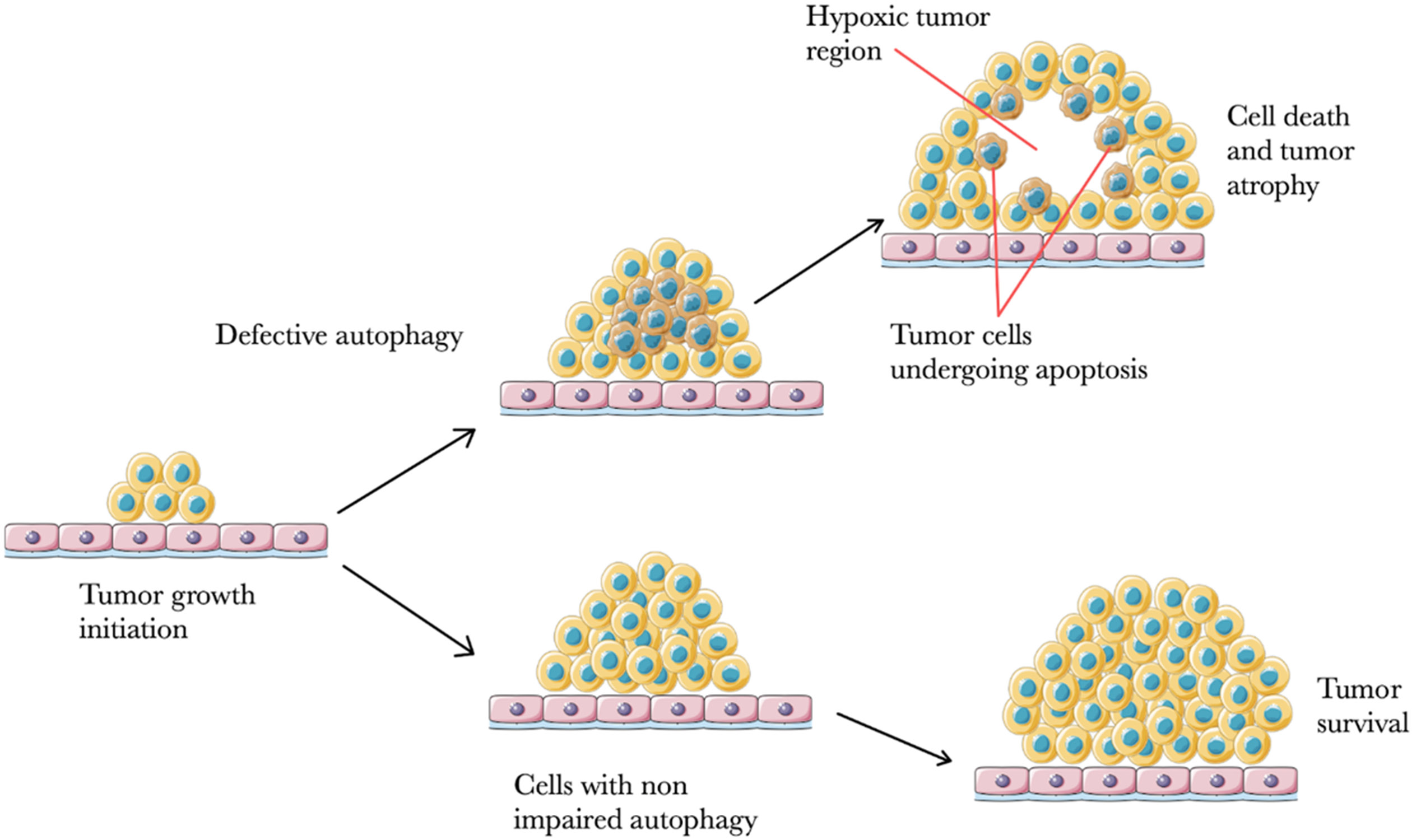

The role of autophagy in cancer is a double-edged sword. Under physiological conditions and a functional autophagy apparatus, a cell exposed to unfavorable factors (mentioned above) can recover. For instance, a cell is exposed to ROS and the damaged proteins emerge. Autophagy activates to adequately degrade the damaged proteins and organelles, averting potential carcinogenesis. On the other hand, when autophagy is impaired and the cellular response is inadequate, damaged proteins and organelles accumulate, and further oxidative stress results in DNA damage and genome instability. Many cells undergo apoptosis or necrosis when the damage is fatal, but others may mutate unfavorably. The effect of these mutations may result in chronic inflammation, compensatory proliferation to replace lost cells, and tumor initiation. In this instance, before carcinogenesis occurs, autophagy, as a protective mechanism, mitigates the damage done through various factors and prevents a tumor-initiating environment from occurring. The opposite happens once carcinogenesis has begun. Defective autophagy, in this instance, can lead to a better response of cancer cells to treatment, hypoxia and, in some cases, cancer cells death and tumor atrophy. This is because cancer cells are considered to be more autophagy-dependent than noncancerous cells. It is especially applicable to cancer cells within the central part of tumors, as this environment is notorious for nutrient deficiencies and oxygen deprivation. Additionally, these cells have higher bioenergetic and biosynthetic needs due to their high proliferation rates. It has been proven that autophagy in the central cells is significantly more intense, compared to those in the tumor periphery. In this case, autophagy might be seen as a mechanism that allows for the survival and even proliferation in highly unfavorable conditions, leading to further growth, invasion and propagation of metastases (Figure 4).

By promoting the survival of cancer cells, autophagy also influences future phases of tumor development. The initial steps of metastasis require signals promoting migration and invasion. Many types of cells, such as inflammatory cells, can provide such signals.55 Various inflammatory cells infiltrate the tumor reacting to necrosis, commonly seen in solid tumors, and produce different effects on the tumor. Natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes generally have anti-metastatic influence, while macrophages in the tumor environment usually correlate with a poor clinical prognosis.56 By promoting the survival of tumor cells under metabolic stress and hypoxic conditions, autophagy reduces tumor cells necrosis and tumor infiltration through pro-metastatic mediators, such as macrophages. Therefore, in the early stages of metastasis, autophagy may act as a suppressor of metastasis, necrosis, and consequently tumor infiltration by inflammatory cells. However, in the later stages of metastasis, metastatic cells enter the circulation, and autophagy is a factor that allows them to overcome anoikis.57 In normal cells, the detachment from the extracellular matrix (ECM) propagates apoptosis, termed anoikis. Autophagy has been proven to have a role in anoikis resistance, as the knockdown of Atg proteins enhances cell death after ECM detachment.58 Therefore, autophagy is a factor facilitating the survival and dissemination of metastatic cells. The final step in the metastasis cascade is the colonization of a distant organ within the host. As the environment in secondary organs differs from the primary site of the tumor, metastatic cells must adapt to the new conditions.59 For example, metastatic cells that invade the lungs encounter an oxygen-rich environment and must adapt to the increased oxidative toxicity. As stated above, autophagy is the mechanism that allows for the survival and further development of cancer cells. Some studies have also proven that when metastatic cells are unable to adapt to the new environmental conditions, they may enter into a dormant state.60 Thus, during different stages of cancer development, the impairment or stimulation of autophagy can be beneficial, and the clinical application of both autophagy inhibitors and stimulants may be an answer to the therapeutic challenges of cancer treatment (Table 1).

Cancer cachexia

and autophagy processes

Cachexia is a syndrome caused by many factors that are often observed in oncological patients but can occur in a spectrum of non-oncological chronic diseases.61 We do understand the causes of cachexia to some extent – chronic systemic catabolism and inflammation are described as the 2 main components of this process, although its etiology may differ in various tumor types.62 It is usually associated with the progressive loss of lean body mass (with or without fatty tissue) through the involuntary degradation of skeletal muscle. Cachexia can result in impaired functionality of the human body displayed as immune system malfunction, nausea, asthenia, anorexia, energy imbalance, and neuroendocrine changes.63 Cancer cachexia affects 50% of all cancer patients in the early stages of the disease and 80% as the disease advances,64 making it a concerning challenge for medicine. Cachexia can affect the entire organism by reducing the quality of life, tolerance, response to treatment, and consequently, survival. Inflammatory factors described in cancer cachexia are eicosanoids,65 tumor necrosis factor, interferon, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β.66 Chronic inflammatory processes can lead to increased fatty acid content within the blood.67 Pettersen et al. found that IL-6 secreted by tumor cells stimulates autophagy in myotubes when complexed with soluble IL-6 receptors.68 Poor prognosis has also been described in lung cancer patients with elevated IL-6 levels.68 Systemic chronic inflammation, characteristic in cancer cachexia, is a result of immune cell infiltration of the tumor microenvironment and constant stimulation of the immune system by cancer. Systemic inflammation increases the demand for nutrients and energy through catabolic upregulation. Selective autophagy is a process induced by various forms of stress – ROS and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) accumulation, hypoxia and inflammation. It ensures a continuous supply of energy and nutrients for a tumor as a functional adaptive cellular response. Penna et al. demonstrated that muscle atrophy occurring in cancer cachexia is associated with an augmented autophagy rate by studying markers of the process – Beclin-1 (autophagy induction marker), LC3B conversion (autophagosome levels) and p62/SQSTM1 (substrate sequestration).69 Another study, looking at the association between weight loss and autophagy-accelerated bioactivity, showed no link in a heterogeneous group of oncological patients. However, a different study focusing on lung cancer patients indicated that autophagy-induced activity and weight loss was a characteristic in men only and was responsible for a worse prognosis.70

Oncogenes and tumor suppressors involved in autophagy

Years of studies on oncogenesis and autophagy identified shared genes in both processes.71 Today we know that both oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes play a part in autophagy. An oncogene, AKT1, has been identified as an inhibitor of autophagy via mTOR activation.72 Mutations in the Ras gene are common in several types of aggressive cancers and also play a crucial role in autophagy.73 The Ras gene is a known upstream inhibitor of mTOR. On the other hand, PI3K inhibits autophagy via AKT1 activation and is responsible for the gain-of-function mutations seen in tumor cells.71, 72 The Bcl-2 gene is known for its anti-apoptotic characteristics and inhibition of Beclin-1,73 a crucial protein in the initial stages of macroautophagy. Beclin-1 is also considered a tumor suppressor gene that is commonly deleted in breast, ovarian and prostate cancers.73 The NF1 is a suppressor often mutated in von Recklinghausen’s disease and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, and can relieve Ras-mediated inhibition of autophagy.73 The TSC1 and TSC2 genes are mutated in tuberous sclerosis and indirectly inhibit the PI3K-AKT1-mTOR pathway.74 Another tumor suppressor gene, RAB7A, is known for its rearrangement in leukemias, deletion in solid tumors and involvement in autophagosomal maturation.75 The DAPK1, yet another suppressor gene silenced in various tumors, relieves the inhibition of autophagy mediated by Bcl-2/Bcl-XL.76 The PTEN gene is downregulated in ovarian cancer and stops autophagy inhibition mediated by PI3K-AKT1.72 These examples highlight the fact that autophagy and carcinogenesis have a lot in common.

Treatment opportunities

The research on autophagy has brought to light new cancer treatment possibilities.77 Thanks to the dualistic role of autophagy in cancer initiation and progression, there are many areas we can target to capitalize on the effect of autophagy in order to suit clinical treatment. Considering that autophagy has an important role in tumor suppression, we can try to modulate and enhance it in patients with an increased risk of developing cancers (Table 2). On the other hand, once carcinogenesis has occurred, the inhibition of autophagy in cancer cells can be very beneficial. The 3rd potential application of our knowledge regarding autophagy is in modulating it to increase the susceptibility of a tumor to radio- and chemotherapy.78, 79

ULK inhibitors

The ULK proteins have a vital and comparatively well-researched role in autophagy induction and have been one of the main focuses of numerous studies. Many compounds involved in the inhibition of ULK kinase activity have been identified: compound 6, MRT68921, MRT67307, SBI-0206965, ULK100, and ULK101.77 The most researched compound is SBI-0206965. It has been proven to reduce the growth and induce apoptosis in some neuroblastoma cell lines, and sensitize one line to treatment. Furthermore, it suppresses non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell growth, enhances its susceptibility to cisplatin, and even induces apoptosis in clear cell renal carcinoma (i.e., by blocking autophagy).80, 81 Some studies have also indicated its utility in the potential treatment of myeloid leukemia FLT3-ITD.82

Autophagosome formation inhibition

Since autophagosome formation is an essential stage in macroautophagy, there have been studies to find a compound that suppresses it. Verteporfin disrupts autophagosome formation and other pathways in autophagy.83 Research has shown that verteporfin sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to cytotoxic drugs.84

Lysosomes inhibitors

Lysosome function in autophagy prompted studies on chloroquine (CQ) and its analog hydroxychloroquine. Both substances are known for their use in malaria treatment and rheumatoid diseases, and their application in cancer therapy seems to be the next step. It is known that they can inhibit autophagy by directly interacting with lysosomes. As weak bases, they diffuse into the lysosome and undergo protonation to cause overall alkalization of the lysosome lumen. This creates an unfavorable environment for lysosomal enzymes and impairs their function. A protonated CQ cannot then diffuse out of the lysosome as it loses its ability to transverse cell membranes.85 Chloroquine also inhibits the fusion of the lysosome with the autophagosome.86 Importantly, those effects did not go unnoticed and CQ has already entered clinical trials in combination with taxane and taxane-like drugs to evaluate the response of breast cancer cells to this drug combination.87 The challenge of long-term use of CQ and its derivatives is their well-known toxicity, which highly depends on the dose and duration of treatment. The most common side effects are retinopathy and cardiotoxicity.88, 89

Another drug with similar effects on lysosomes is bafilomycin A1 (BafA1). It also alkalizes the lumen of lysosomes through a different mechanism than CQ. The BafA1 targets the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, a transmembrane proton pump responsible for acidifying the lysosome.90 Similarly to CQ and its derivatives, it also inhibits the autophagosome-lysosome fusion and impairs TORC1 signaling. Thus, many researchers speculate about BafA1 future use in cancer treatments.91

mTOR inhibitors

The name of mTORC1 derived from the fact that it is a target of rapamycin.92 Rapamycin is a macrolide compound known for its role in transplant surgery (administered to prevent transplant rejection) and coronary stent coating. Additionally, studies have shown, that it might be considered an anti-aging drug (e.g., it extended the lifespan of mice in some studies).93 These effects are mainly due to its inhibition of mTOR proteins and consequently, autophagy activation. Many researchers have suggested that rapamycin could be used to slow down most (if not all) age-related diseases in humans, including some cancers.94 Because mTOR activity is commonly upregulated in cancer, its inhibitors have significant promise in cancer therapy.95 Therefore, rapamycin and its derivatives (known as rapalogs) such as temsirolimus, everolimus and ridaforolimus are undergoing clinical trials to evaluate their potential use in cancer treatment. Temsirolimus has already been approved by the The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007 for use in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) treatment.

PI3K inhibitors

The critical role of PI3K in autophagy inspired the research into compounds able to block its function.96 Several molecules have been found, such as 3-methyladenine (3-MA), LY294002, wortmannin, and its analog PX-866 (Oncothyreon). Clinical trials have been conducted using PX-866 on patients with advanced prostate cancer, although only modest single-agent activity has been reported. However, more research concerning the activity of PX-866 combined with other drugs needs to be conducted.97 Additionally, the compounds able to inhibit both PI3K and mTOR, such as NVP-BEZ235 and GDC-0980, have entered clinical trials evaluating their potential use in cancer therapy.

PI3KC3 complex inhibitors

Since PI3KC3 complexes consist of various proteins, there are a few ways to block their activity. The SAR405 is a selective Vps34 inhibitor that affects late autophagosome-lysosome interaction and prevents autophagy.98 Furthermore, the available research has shown that SAR405 combined with everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) to produce strong antiproliferative effects on renal tumor cells.99 The potential drawback of SAR405 administration is that PI3KC3 is also involved in endosomal trafficking and therefore, can negatively affect cellular secretion.

Spautin-1 is a compound that impairs PI3KC3 by a different approach. It inhibits autophagy by enhancing the degradation of Beclin-1 and thus, prevents the formation of the PI3KC3 complex.100 Shao et al. reported promising results with its potential application in overcoming resistance to imatinib mesylate-induced autophagy in chronic myeloid leukemia.101 Not only does it show proapoptotic properties, but it also potentiates the efficacy of imatinib mesylate in chronic myeloid leukemia cells.

BH3 mimetics

The theory behind administering BH3 mimetics is to stimulate autophagy in cells by liberating Beclin-1 from Bcl-2.102 Stimulating this interaction can be beneficial also because of the possibility of inducing apoptotic cell death by negating the anti-apoptotic effects of the Bcl-2-Bax complex. Gossypol is a polyphenolic aldehyde that works as a pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor.103 Clinical trials have been conducted in patients with glioblastoma and despite some adverse events (including cardiac and gastrointestinal disorders), the results are promising.104 Another BH3-mimetic drug, ABT-737 has been tested on various thyroid carcinoma cell lines and has been proven to cause apoptotic cell death and a synergistic effect with chemotherapeutic drugs.105 Furthermore, there is an analog of ABT-737 that can be administered orally, ABT-236. Although the clinical application for our constantly evolving knowledge about autophagy is within our grasp, there is still a magnitude of research that needs to be conducted.

Conclusions

From many years of studies, we have learned a lot about autophagy and its role in the pathogenesis of certain diseases. As far as our understanding of the molecular pathways of autophagy is concerned, their relation to cancer seems to be more profound and sophisticated than initially anticipated. We know that it is a housekeeping mechanism of a cell that decreases chances of neoplastic transformation, but after malignant transformation, it supports the proliferation and prosperity of cancer cells. Confirming autophagy as a mechanism that promotes tumor growth, provides us with the knowledge to develop new treatment options for oncologic patients and brings hope to the idea of curing cancer.